Abstract

The hypothesis that respiratory modulation of heart rate variability (HRV) or respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) is restricted to mammals was tested on four Antarctic and four sub-Antarctic species of fish, that shared close genotypic or ecotypic similarities but, due to their different environmental temperatures, faced vastly different selection pressures related to oxygen supply. The intrinsic heart rate (fH) for all the fish species studied was ∼25% greater than respiration rate (fV), but vagal activity successively delayed heart beats, producing a resting fH that was synchronized with fV in a progressive manner. Power spectral statistics showed that these episodes of relative bradycardia occurred in a cyclical manner every 2–4 heart beats in temperate species but at >4 heart beats in Antarctic species, indicating a more relaxed selection pressure for cardio-respiratory coupling. This evidence that vagally mediated control of fH operates around the ventilatory cycle in fish demonstrates that influences similar to those controlling RSA in mammals operate in non-mammalian vertebrates.

Keywords: notothenioids, Antarctic fish, power spectral analysis, cardio-respiratory coupling

In mammals, baroreceptor responses are gated during inspiration and the efferent, inhibitory vagal supply to the heart is modulated by respiratory activity (Jordan & Spyer 1987). Power spectral analysis (PSA), which identifies frequency oscillations in time signals, of heart rate variability (HRV) in mammals shows that some fluctuations in heart rate (fH) appear as distinct peaks in the spectral bandwidth, at the frequency of the ventilatory cycle (Akselrod et al. 1981). Consequently, regular fluctuations infH are coupled with ventilation rate (fV), a phenomenon termed respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA). Pharmacological parasympathetic blockade abolishes this relationship, indicating that the predominant factor generating RSA is respiration-related fluctuations in vagal influence on the pacemaker at the sinus node (Medigue et al. 2001).

Although cardio-respiratory synchrony has been reported in some fish species and pharmacological parasympathetic blockade abolished a 1 : 1 synchrony between fH and fV in unrestrained dogfish (Taylor 1992), the few PSA studies that have examined heart rate variability (HRV) in teleosts have found no high frequency component associated with vagal control (Armstrong et al. 1988; De Vera & Priede 1991; Altimiras et al. 1996; Altimiras 1999). It was further proposed that RSA may be of limited significance in fish because fV is always equal to or greater than fH (Kazlauskene et al. 1987). Despite this lack of RSA-type modulation, Myoxocephalus scorpius showed a close association between the re-establishment of HRV and recovery of MO2 after surgery (Campbell et al. 2004). Furthermore, respiration-related activities have been recorded both in the afferent fibres and cardiac efferent fibres of the vagus nerve, and phasic electrical stimulation of the branchial or cardiac nerves can recruit the heart (Taylor et al. 1999). These observations are consistent with a central, feed-forward and/or reflex control matching water and blood flow at the gills.

In addition to these data on fish, it has been observed that many amphibians and reptiles, characterized as breathing discontinuously, show close correlations between the onset of a bout of breathing and an instantaneous tachycardia, implying overriding central nervous integration of their cardio-respiratory systems (Burggren 1987). However, Porges (1995) proposed that cardio-respiratory coupling is restricted to mammals.

In order to test whether cardio-respiratory coupling can be demonstrated in fish, and may function as a mechanism to optimize oxygen uptake, eight fish species that showed unique genotypic and ecotypic relationships were examined. Four were nototheniid species from the Southern Ocean (environmental temperature −1.8 to 0 °C), compared with two notothenioids and two unrelated species from temperate waters (8–12 °C) (see table 1). All these fish were of a similar ecotype, being demersal labriform swimmers, spending a large proportion of their time resting on the seabed. Gas solubility is inversely proportional to temperature, and at 0 °C water contains about 1.6 times as much oxygen as at 20 °C. Therefore, Antarctic fishes may never experience hypoxic conditions, while it can be a common problem for temperate species.

Table 1.

Eight species of fish of similar ecological type (MacDonald et al. 1987), were monitored for resting fH and fV (* indicates temperate notothenioids).

| species | envi-temp (°C) | intrinsic fH | resting fH | resting fV | coefficient ofvariation | lowF/highF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trematomus bernacchii | −1.8 | 22.2±0.7 | 14.3±2.4 | 15.7±3.4 | 19.26±1.1 | 1.41±0.4 |

| Trematomus nicolai | −1.8 | 24.1±0.9 | 15.3±3.4 | 17.1±3.4 | 15.89±0.6 | 1.35±0.4 |

| Trematomus hansonii | −1.8 | 22.3±1.1 | 14.6±3.2 | 17.6±4.1 | 16.2±1.4 | 1.42±0.6 |

| Trematomus pennelli | −1.8 | 25.5±0.8 | 14.6±2.6 | 18.7±3.2 | 16.5±0.9 | 1.43±0.1 |

| Paranotothenia angustata* | +10 | 46.6±0.9 | 30.2±2.1 | 34±3.2 | 16.8±1.8 | 0.45±0.2 |

| Bovichtus variegates* | +10 | 43.1±1.2 | 28.4±3.2 | 30.4±2.8 | 15.2±2.1 | 0.65±0.1 |

| Karalepis stewarti | +10 | 44.2±1.0 | 27.3±2.5 | 30±3.1 | 16.6±1.3 | 0.56±0.2 |

| Myoxocephalus scorpius | +10 | 32.2±1.1 | 18.1±2.6 | 20±3.4 | 18.1±1.4 | 0.71±0.1 |

After 48 h tank acclimation fish were anaesthetized (3 mg l−1 MS222), teflon-coated stainless steel recording electrodes (0.2 mm) were attached to record instantaneous electrocardiograms (e.c.g.) and opercula movement (baseline artefact). Fish were given a 96 h undisturbed rest before 1 h traces were recorded. Intrinsic heart rates were determined by complete autonomic blockade via infusion of atropine and propranalol (1 mg kg−1) by indwelling intra-peritoneal cannulae (methods in Campbell et al. 2004). Ethical approval was covered by The Animal (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986. Coefficient of variation was calculated as (mean R–R interval/S.D. of R–R interval). The powers of low frequency and high frequency components were determined for individual fish spectra before grouping.

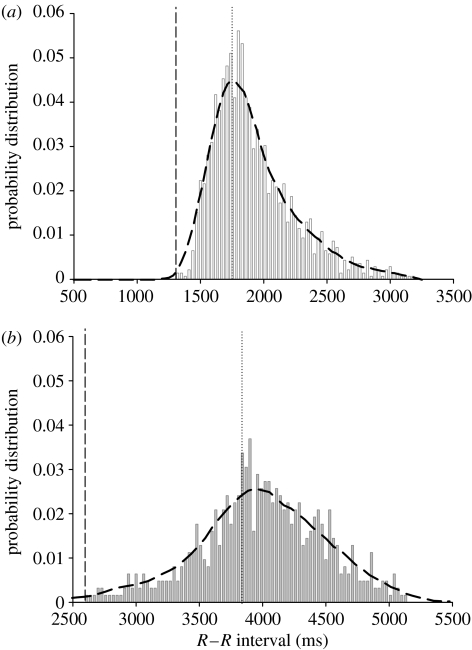

Instantaneous electrocardiograms (e.c.g.) and the ventilatory cycle were recorded in resting fish. Both fH and fV were lower in Antarctic fish compared to temperate fish, but shared a similar temporal relationship. Intrinsic fH was approximately 25% less than fV, but firing from the sinus node was delayed by vagal tonus over the succeeding ventilation cycle, to produce a mean resting fH that oscillated around the less variable ventilation cycle fV (figure 1a,b). Fluctuations in fH were not synchronous with ventilatory rhythms but appeared to be affected by them, with species from similar thermal environments showing a similar relationship. The probability distribution for R–R intervals (time interval between heart beats) plotted for temperate fish displayed a positively skewed, log-normal distribution, compared with the flatter, Guassian curve with shorter tails exhibited by Antarctic fish. The difference in distribution of R–R intervals between thermal groups requires frequency domain spectral statistics to elucidate its origin.

Figure 1.

(a) Probability distribution of 750 consecutive R–R intervals grouped into 30 ms bins for the temperate fish P. angustata (n=6). Log-normal distribution curve fitted to data (Shapiro-Wilks test=P<0.1; standard skewdness=3.13). (b) Probability distribution of 750 consecutive R–R intervals in 30 ms bins for the Antarctic T. bernachii (n=6). Normal distribution curve fitted to the data (Shapiro-Wilks test=P<0.1; standard skewdness=1.7). Vertical dashed line indicates length of intrinsic heart rate, and the dotted line the ventilation cycle.

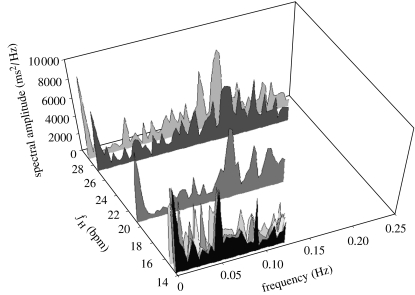

The Fourier (time-to-frequency) transform (FT) was applied to the e.c.g. tachogram, where sampling frequency for an individual fish was determined by its own fH. In converting the time signal to the frequency domain the FT algorithm requires two samples in the time domain for every one in the frequency domain (Malik & Camm 1995). Therefore, in applying the FT to the R–R interval time series the maximum sampling frequency (Fs(max)) will be:

The upper limit to the resultant spectrum is called the Nyquist criterion (N), and as the Antarctic fish had a much lower mean fH than temperate fish, N was reduced accordingly (figure 2). This provided an efficient standardization technique for comparing physiological oscillations between species with vastly different fH. The interpretation of peaks relating to fV differs from the mammalian model, where the single high frequency peak indicating RSA is caused by ventilatory modulation, which is only possible when fV<2fH. In fish this is not the case and therefore fV cannot be exhibited as a discrete frequency in the spectrum, but instead will appear as a diffused number of peaks scattered systematically in the spectral bandwidth. Similar effects have been observed in human neonates (Zweiner et al. 1995). For all fish examined here, the FT spectra indeed consisted of multiple peaks, which showed both inter-specific and intra-specific variability. Therefore, to enable appropriate conclusions with regard to underlying oscillations affecting relative fH for an individual fish, the spectrum was divided exactly in half, with spectral peaks falling either side of this boundary being assigned either low frequency (LF) or high frequency (HF) status. As the inherent laws of the FT mean N will always be equal to two samples (R–R intervals), we can calculate the time domain equivalent for the spectrum frequency components:

Simple division (LF/HF) of the relative low and high powers in the spectrum will provide a measure of the dominant oscillations responsible for overall HRV. This ratio was always <1 in temperate fish, indicating the significance of HF beat-to-beat components in determining overall HRV (table 1). In Antarctic fish the LF/HF ratio was always >1 and therefore the oscillatory components responsible for overall HRV occurred at a frequency >4 heart beats. That these variations were oscillatory components being controlled centrally by vagal tonus was demonstrated by bilateral vagotomy, which abolished all peaks (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Power spectra calculated from the resting instantaneous e.c.g. from four Antarctic and four temperate fish species. Raw e.c.g. traces were examined and sections of 3×512 consecutive R–R intervals without ectopics or artefacts were selected, tested for stationarity and underwent fast Fourier transformation (FFT) analysis using a Hanning window to reduce spectral leakage, with the resulting spectra being plotted graphically (see methods Altimiras 1999). Each spectrum length is set by the Nyquist criterion, which is in turn determined by the individual fishes’ actual heart rate. Antarctic species: 14.3 bpm=T. bernacchii (n=5), T. pennelli (n=5), 14.6 bpm=T. hansoni (n=5), 15.3 bpm=T. nicolai (n=5); temperate species: 20.6 bpm=M. scorpius (n=5), 27.2 bpm=B. variegatus (n=5), 28.9 bpm=P. angustata (n=6). (For clarity 46 bpm=the temperate K. stewarti (n=5) was omitted).

All fish studied utilised vagal modulation to delay the firing of the sinus node, and so resting fH became more synchronized around the respiratory cycle. Fish cannot exhibit the classic RSA as observed in mammals due to the quantitative similarities of fH and fV, but instead a systematic distribution of oscillatory components is evident in the power spectrum due to the interaction of fH and fV. The decreased beat frequency of these oscillations in Antarctic fish, where the selection pressure of limited oxygen supply is reduced, suggests that they may serve to synchronize blood and water flow at the gills and so optimize oxygen uptake and delivery.

These data from fish can be compared with data from other non-mammalian vertebrates. Recent experiments demonstrated increases in heart rate and pulmonary blood flow during bouts of fictive breathing in decerebrate, paralysed and ventilated toads (Wang et al. 1999) and, in conscious Xenopus, denervation of pulmonary stretch receptors did not abolish the increase in heart rate associated with lung inflation (Evans & Shelton 1984). Both results indicate central control of cardio-respiratory interactions. In reptiles, complete vagotomy in the rattlesnake caused heart rate to rise and abolished a respiration-related variability. The breathing rhythm slowed, accompanied by large lung volumes (Wang et al. 2001). These data can be interpreted as loss of vagal tone on the heart, which seems to be responsible for HRV as well as setting the overall fH, plus denervation of lung stretch receptors. Recent experimentation that used power spectral analysis of HRV in the rattlesnake revealed clear respiration-related components, that can be characterized as RSA (Campbell et al., unpublished data). We therefore reject the hypothesis that centrally controlled cardio-respiratory coupling is restricted to mammals, as propounded by the polyvagal theory of Porges (1995).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NERC (NER/G/S/2000/00600). The help of Lloyd Peck and Keiron Fraser of The British Antarctic Survey, Bill Davison of Antarctic New Zealand, and staff of Portobello Marine Laboratory is greatfully acknowledged.

References

- Akselrod S, Gordon D, Ubel F.A, Shannon D.C, Barger A.C, Cohen R.J. Power spectrum analysis of heart rate fluctuations: a quantitative probe of beat-to-beat cardiovascular control. Science. 1981;213:220–222. doi: 10.1126/science.6166045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altimiras J. Understanding autonomic sympathovagal balance from short-term heart rate variations. Are we analyzing noise? Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. 1999;124:447–460. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(99)00137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altimiras J, Johnstone A.D.F, Lucas M.C, Priede I.G. Sex differences in the heart rate variability spectrum of free-swimming atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) during spawning season. Physiol. Zool. 1996;69:770–784. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong J.D, DeVera L, Priede I.G. Short-term oscillations in heart rate of teleost fishes: Esox lucius L. and Salmo trutta L. J. Physiol. Lond. 1988;409:41. [Google Scholar]

- Burggren W.W. Form and function in reptilian circulations. Am. Zool. 1987;27:5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell H.A, Taylor E.W, Egginton S. The use of power spectral analysis to determine cardiorespiratory control in the short-horned sculpin Myoxocephalus scorpius. J. Exp. Biol. 2004;207:1969–1976. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00972. doi:10.1242/jeb.00972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vera L, Priede I.G. The heart rate variability signal in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) J. Exp. Biol. 1991;156:611–617. [Google Scholar]

- Evans B.K, Shelton G. Ventilation in Xenopus laevis after lung or carotid labyrinth denervation. Proc. First Int. Congr. Comp. Physiol. Biochem. Liege. 1984;1:A75. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan D, Spyer K.M. Central neural mechanisms mediating respiratory–cardiovascular interactions. In: Taylor E.W, editor. Neurobiology of the cardiorespiratory system. Manchester University Press; Manchester: 1987. pp. 322–341. [Google Scholar]

- Kazlauskene N.P, Zemaityte D.I, Plauska V.V. Spectral analysis of cardiac rhythm in fish. J. Evol. Biochem. Physiol. 1987;23:359–363. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald J.A, Montgomery J.C, Wells R.M.G. Comparative physiology of Antarctic fishes. Adv. Mar. Biol. 1987;24:321–388. [Google Scholar]

- Malik M, Camm A.J. Futura Publishing; Oxford: 1995. Heart rate variability. [Google Scholar]

- Medigue C, Girard A, Laude D, Monti A, Wargon M, Elghozi J. Relationship between pulse interval and respiratory sinus arrhythmia: a time and frequency-domain analysis of the effects of atropine. Eur. J. Physiol. 2001;441:650–655. doi: 10.1007/s004240000486. doi:10.1007/s004240000486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges S.W. Orienting in a defensive world—mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage—a polyvagal theory. Psychophysiology. 1995;32(4):301–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1995.tb01213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor E.W. Nervous control of the heart and cardiorespiratory interactions. In: Hoar W.S, Randall D.J, Farrell A.P, editors. Fish physiology. vol. 22B. Academic Press; New York: 1992. pp. 390–426. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor E.W, Jordan D, Coote J.H. Central control of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems and their interactions in vertebrates. Physiol. Rev. 1999;79:855–916. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.3.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Taylor E.W, Reid S.G, Milsom W.K. Lung deflation stimulates fictive ventilation in decerebrated and unidirectionally ventilated toads. Respir. Physiol. 1999;118:181–191. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(99)00081-x. doi:10.1016/S0034-5687(99)00081-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Warburton S, Abe A.S, Taylor E.W. Vagal control of heart rate and cardiac shunts in reptiles: relation to metabolic state. Exp. Physiol. 2001;86:777–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-445x.2001.tb00044.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-445X.2001.tb00044.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwiener U.L, Bauer R, Hoyer D, Richter A, Wagner H. Heart rate fluctuations of lower frequencies than the respiratory rhythm but caused by it. Eur. J. Physiol. 1995;429:455–461. doi: 10.1007/BF00704149. doi:10.1007/BF00704149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]