Abstract

Background

The identification of chromosomal homology will shed light on such mysteries of genome evolution as DNA duplication, rearrangement and loss. Several approaches have been developed to detect chromosomal homology based on gene synteny or colinearity. However, the previously reported implementations lack statistical inferences which are essential to reveal actual homologies.

Results

In this study, we present a statistical approach to detect homologous chromosomal segments based on gene colinearity. We implement this approach in a software package ColinearScan to detect putative colinear regions using a dynamic programming algorithm. Statistical models are proposed to estimate proper parameter values and evaluate the significance of putative homologous regions. Statistical inference, high computational efficiency and flexibility of input data type are three key features of our approach.

Conclusion

We apply ColinearScan to the Arabidopsis and rice genomes to detect duplicated regions within each species and homologous fragments between these two species. We find many more homologous chromosomal segments in the rice genome than previously reported. We also find many small colinear segments between rice and Arabidopsis genomes.

Background

Exploration of homology between chromosomes facilitates the understanding of the structure, function and evolution of genomes. Extensive synteny and colinearity have been detected between chromosomes in different species of cereals [1], mammals [2] and yeasts [3] providing a deep insight into the evolution of ancient chromosomes. Between chromosomes of the same species, large-scale homologous segments exist caused by whole genome or segmental duplication [4-9]. It has been reported that nearly 80% of the Arabidopsis thaliana genome and 45–60% of the rice genome are in large duplicated regions [10-12].

Special care should be taken to reveal chromosomal homology due to numerous genomic changes such as chromosomal rearrangements, gene inversions and gene loss [13-15]. Many approaches have been developed to identify chromosomal homologues [16] based on genetic maps [17], sequence alignment [18,19], gene synteny [10] and gene colinearity [20-23]. By detecting the density and order of homologous gene pairs between chromosomes, colinearity approach can reveal reliable homologous regions and requires less computational resources. This approach also enables us to develop reasonable statistical tests to evaluate the significance of predicted homologous regions.

The typical implementations of the colinearity strategy are ADHoRe [20], FISH [24] and DiagHunter [25]. The implementations of these approaches have limitations in some aspects, though they have been widely adopted. Firstly, the gap size between neighboring homologous genes which is essential to define and detect true colinearity needs further evaluation [12,20-23,26]. Secondly, statistical tests to assess predicted homologous regions are mainly based on a prerequisite of balanced gene loss rates between homologous regions. Finally, compositional and structural differences, especially gene density and repetition in genome-wide and local chromosomal regions, have not been fully addressed.

Here we describe a new colinearity approach characterized by improved statistical inference, flexibility and computational efficiency. Firstly, the selection of parameter values is theoretically explored, especially that of the gap length between neighboring genes. Secondly, the statistical test has been substantially strengthened with a mathematical deduction to evaluate the significance of the predicted homologous regions. Finally, the compositional and structural heterogeneity of chromosomes has been considered.

Using a dynamic programming algorithm, we developed ColinearScan and scanned the Arabidopsis and rice genomes to detect duplicated regions in each species and homologous chromosomal regions between these two species. We found 75.0% of Arabidopsis genes and 76.2% of rice genes were in duplicated regions. Moreover, we identified homologous fragments between these two species, in 32.9% of Arabidopsis and 16.8% of rice. Nearly all homologous segments were shorter than 0.6 Mb, indicating massive chromosomal rearrangements after the monocot-dicot divergence [27].

Results

Algorithm

Gene homology matrix

The first step in our colinearity approach is the construction of the gene homology matrix. To find homologous gene pairs between two chromosomes denoted as A and B, protein sequences encoded by genetically or physically positioned genes are used to perform an all-against-all BLAST search [28]. A gene homology matrix (GHM, denoted as H) is then constructed using the homology information from BLAST results. Chromosome A and B, represented by the positioned genes are arranged along H horizontally and vertically (Fig. 1A). A cell of H is filled with "1" if the corresponding genes on chromosome A and chromosome B are homologous, otherwise with "0". Tandem and other repetitive genes are widely distributed in chromosomes showing many "1"s in horizontal or vertical straight lines in the dot matrix map (Fig. 2) and causing problems in revealing true homology. Therefore, we used a general approach, masking the genes appearing more than 10 times in both chromosomes.

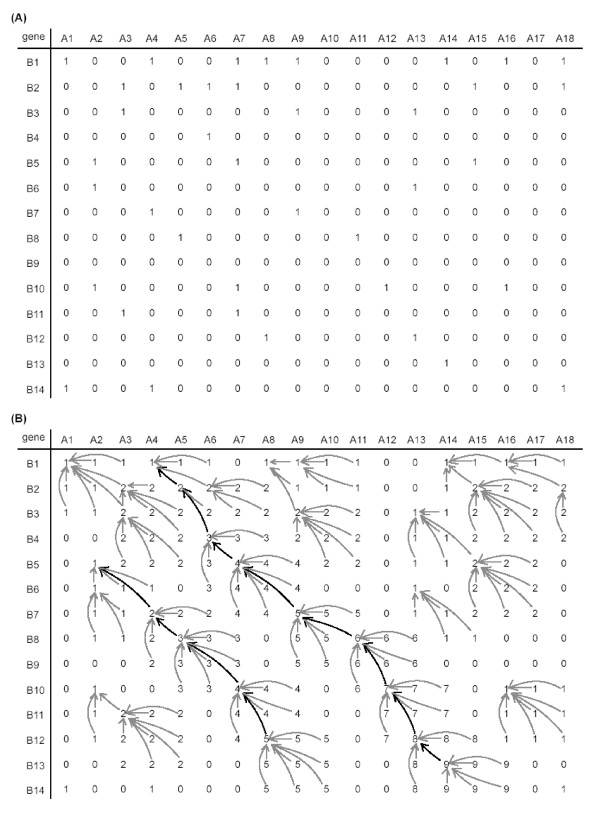

Figure 1.

A modified Smith-Waterman algorithm to locate colinearity. (A) A simplified gene homology matrix (GHM, denoted as H). Genes A1, A2, ..., A18 on chromosome A are arranged horizontally, and genes B1, B2, ..., B14 on chromosome B are arranged vertically. Each cell of the matrix is filled with "1" or "0" based on the homology information from BLASTP search, e.g., gene A1 and gene B1 are homologous, and gene A2 and B2 are non-homologous. (B) A modified dynamic programming procedure. A scoring matrix S is constructed recursively based on H, with mg set to 2 genes apart. The distance criterion demands that neighboring genes in colinearity are no more than 2 genes apart. Pointers are shown by dark or grey arrow lines. Two collinear paths containing 9 and 5 genes are shown by dark arrow lines reflecting the same colinear relationship between the corresponding chromosomal regions.

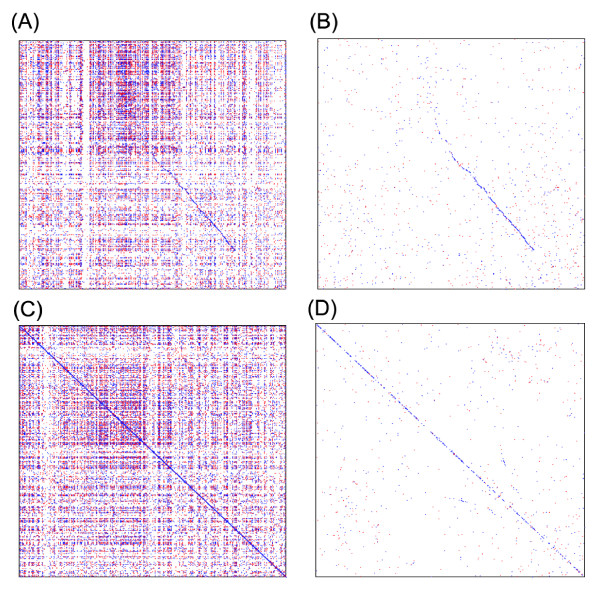

Figure 2.

Examples of dot maps. (A) A dot map between rice chromosomes 2 and 4. Each dot in the map reflects a homologous gene pair with BLASTP score > 100. The dots are not distributed uniformly in the map. The map is also featured by many horizontal and vertical lines formed by repetitive genes. (B) A dot map between the same chromosomes as (A) with repetitive genes filtered. (C) A dot map of rice chromosome 1 against itself. Self-matching dots form a solid diagonal line. (D) A dot map with self-matching and repetitive genes filtered. A diagonal line reflecting the neighboring homologues can still be seen.

Dynamic programming algorithm

To reveal the homologous genes in colinearity between two chromosomes, we implemented a dynamic programming approach based on the well-known Smith-Waterman algorithm [29]. Using this approach, we can discover the longest putative sister regions represented by several proximal points of colinear homologous gene pairs in nearly diagonal orientations. The points may not be in close proximity due to large-scale gene loss, insertion and translocation. The extent of the proximity of the points is essential to reveal and evaluate the colinear sister segments. Lines forming by the points corresponding to the true colinear segments are either nearly parallel to the main diagonal line or the anti-diagonal line due to DNA segmental inversion. Homologous genes in colinear segments should all have the same or inverse transcriptional directions if no single gene inversions occur. We scan H in two directions, starting from the upper-left and upper-right. Here, we describe the procedure starting from the upper-left, which also applies in the other direction. Transcriptional orientations of the genes are recorded but not used when performing the colinearity search.

To reveal the colinearity represented by the proximal points in H, we introduce a parameter mg (the maximum gap length) between two neighboring points. Then we define another matrix S (the scoring matrix) with the same size as H (Fig. 1B). A cell in matrix S represents the extension of a colinearity path, i.e., the value of each cell is the number of collinear gene pairs in the path accumulated from its starting point. The path extends and the value of the cell increases by 1 if there is a "1" in lower-right neighborhood, and both vertical and horizontal distances are less than mg.

Initially, S is identical to H. We rebuild the matrix S recursively using a dynamic programming procedure:

where S(i, j) is the score computed, H(i, j) is the homology information, pre(i, j) is the cell leading to the maximum score at the cell p(i, j), and a pointer (denoted by dark or gray arrow lines in Fig. 1B) is created from the cell p(i, j) to pre(i, j), dist(p(i, j), p(a, b)) is the distance between the cells p(i, j) and p(a, b). Eventually, the maximum score in S corresponds to the longest putative collinear segments. The longest colinearity path formed by dots of the homologous gene pairs is revealed by a trace-back procedure according to the pointers created. After the homologous genes in putative colinearity are recorded, we mask these putative colinear segments by setting H(i, j) to 0, rebuild the matrix S, and scan for other putative colinear segments till no sister regions containing more colinear genes than a threshold r could be found.

Maximum gap length

In colinearity methods, mg is the most important parameter which determines the length, quality and extensiveness of the predicated colinearity. The frequency of gene deletion in duplicated chromosomal segments is high and only a small fraction of homologous genes remains in colinearity. A small value of mg will result in finding many small colinear segments, and increase the difficulty of interpreting possible evolutionary events. On the other hand, a large mg value will surely result in high false positives. In fact, mg is dependent on the density of homologous gene pairs between the chromosomes. When the two chromosomes A and B are from the same species, homologous genes between them are mainly distributed at a similar density. On the other hand, when we compare two chromosomes from different species, the density of homologous genes may more divergent. Therefore we adopt two parameters to define the maximum distance between the neighboring dots, the maximum gap between genes in chromosome A (mgA) and the maximum gap between genes in chromosome B (mgB). When the chromosomes are from the same species, we set mgA = mgB.

Under the assumption that homologous genes are uniformly distributed in chromosomes, we explore the possibility of finding sister segments containing equal to or more than r genes by chance. However, this uniform distribution assumption is not very strict since we only need reasonable rather than optimal values of mg. Suppose the length of chromosome A and B are lenA and lenB, and the number of homologous gene pairs between two chromosomes is pnum. The location of a gene is a random variable with a probability density , the joint probability density of the locations of r genes on chromosome A is , and the joint probability density of the locations on chromosome A and B of r homologous pairs is . Therefore, the probability p that r homologous gene pairs are in colinearity by chance can be evaluated by

where the multiple integral field D is

and x1,x2,...,xr;y1,y2,...,yr are the positions of the genes on the chromosomes, is the number of permutations of homologous genes: . When mgA <<lenA and mgB <<lenB, the integral in the above formula can be approximated by

Then we can estimate p by

If we set the significance level of colinearity to α, then we have

When the two chromosomes are from the same species, we assume mgA = mgB and denote them as mg, and the value of mg can be evaluated by

When the two chromosomes are from different species, the gene densities are often different and thus we adopt different values for the parameters mgA and mgB. The length of gaps between neighboring homologous genes is inversely proportional to the density of homologous genes, let

Thus, we can estimate the value of mgA and mgB

Colinearity shadow

Many genes have homologues in their neighborhood as indicated by the distance distribution of homologous genes (Fig. 3). Neighboring homologues may result in many colinear segments parallel to each other in sister regions within the same chromosome, or between the different chromosomes (Fig. 2A, 2C). If for convenience we call the longer ones the 'true' colinearity, then the shorter ones are the 'shadows'. The colinearity shadows may also reflect colinearity, but they do not provide further information and greatly increase the computational time. Thus after a putative colinearity in certain sister regions is found, we mask the neighboring homologous pairs within the corresponding the entire rectangular regions to avoid possible colinearity shadows.

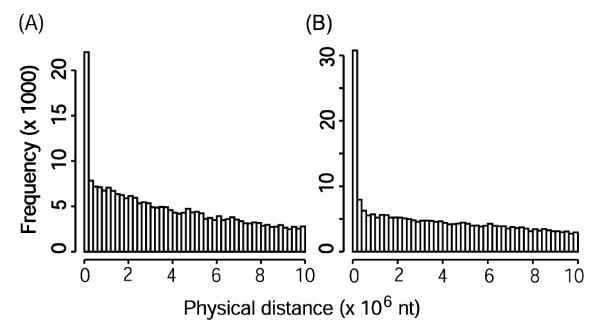

Figure 3.

Distance distribution of homologous genes. (A) The distance distribution of rice homologous genes. (B) The distance distribution of Arabidopsis homologous genes.

When candidate colinearity is found in a specific region of GHM from upper-left to lower-right, colinear shadows perpendicular to this path might also be found in the same region scanning from upper-right to lower-left. These shadows may also reflect actual homology between two sister chromosomal segments, and they may occur when gene rearrangements are frequent in specific regions. A large amount of perpendicular shadows may affect efficiency of the algorithm. However, they do not occur very often so we do not mask these shadows.

Statistical test

Many genes are in multi-gene families and repetitive genes are extensively found in plant genomes. Putative colinear regions might be a reflection of extensive occurrences of single gene duplication or translocation. Therefore, it is critical to correctly detect the colinearity pattern by evaluating the significance of the putative colinear regions generated by the above approach, and to develop an effective statistical method to assess whether the putative colinearity represents true homology or is produced by chance. Moreover, the distribution of homologous gene pairs is far from uniform. We use a statistical test considering divergent distribution of homologous gene pairs in different regions, rather than assuming a uniform distribution throughout the genome.

Given that a DNA segment resides in chromosome B, a corresponding colinear segment in chromosome A is generated due to many independent single-gene duplication events. Under the assumption of a uniform distribution of collinearly paired genes in the local chromosomal regions, we obtain the probability epvA to display the significance of the homology,

where m is the number of collinear gene pairs, is the gap length between paired gene i and gene i-1, is the number of occurrences of the i-th paired gene and its homologues in the putative sister segment in chromosome A, pssA is the length of the sister segment in chromosome A. The above formula can be deduced by extending the colinearity point by point taking repetitive homologues in consideration. The possibility of finding such colinearity under this assumption will be increased by times if homologous genes of the i-th colinear gene exist in this segment. Similarly, we can define the probability epvB

Then we define

epv = max(epvA,epvB)

to measure the possibility of the colinearity appearing by chance in the sister regions. If it is below a threshold, we take the putative colinearity as significant.

However, if we apply the above test directly to the putative different homologous regions, we cannot distinguish between patterns with similar numbers of homologous gene pairs in segments of different size. For example, the putative colinear regions found in small sister segments (Fig. 4B) more likely indicate true segmental homology than that in large sister segments (Fig. 4A). Dense colinearity possibly generated by recent duplications should be evaluated as significant.

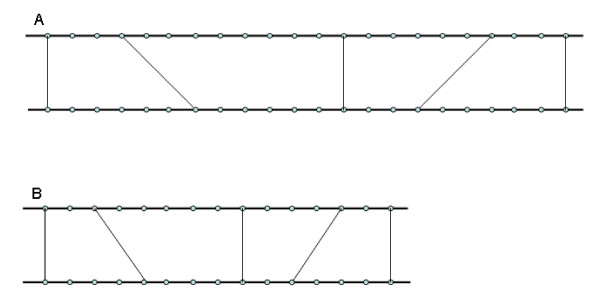

Figure 4.

Different distribution pattern of homologous genes in sister regions. Same numbers of homologous genes located in two pairs of sister regions with different size. Homologue pairs are more densely located in (B) than in (A). Dark horizontal lines represent chromosomes, round dots denote genes on chromosomes, lines linking the dots indicate gene homology.

Rather than using pssA and pssB, we try to estimate epv on expected scales of the sister regions (essA and essB) determined by the numbers of colinear genes and all homologous genes. Assuming that paired genes are uniformly distributed throughout the chromosomes, we estimate the expected sizes for each pair of sister segments as follows

where cnum is the number of colinearly paired genes in the putative sister segments, pnum is the number of all homologous gene pairs between chromosome A and chromosome B, λ is a coefficient to normalize the size of different putative colinear segments. For each pair of putative sister regions we calculate a preliminary coefficient number λi by .

where pssA and pssB are the original sizes of the putative i-th sister segments. These preliminary coefficients are averaged throughout the putative homologous sister pairs to obtain the estimate of λ. Finally, we redefine and

by substituting the original size pssA and pssB with the expected size essA and essB. Thus, we assign different significance to the two patterns in Fig. 4, the sister regions with denser collinear genes have a smaller epv value.

Assessment of mg estimation

To test the applicability of the criteria defining mg, we performed a computational simulation test on rice chromosome 1 and Arabidopsis chromosome 1.

First, using the integral formula (r = 4, α = 0.01, length of rice chromosome 1: lenA = 48.2 Mb, length of Arabidopsis chromosome 1: lenB = 30.5 Mb, pnum = 1737), we calculated the maximum gap length in both chromosomes: mgA = 155 Kb, and mgB = 98 Kb. The parameters r and α mean that using such gap length to scan the homologous segments between the chromosomes, the probability of finding sister segments containing 4 or more collinear genes should be <= 0.01 under the assumption of uniform distribution.

Second, we shuffled the positions of the homologous gene pairs on both chromosomes and scanned the longest homologous segments occurring by chance, then checked whether it had 4 or more collinear genes. We repeated this process 1000 times and found collinear segment with 4 or more collinear genes 9 times.

We calculated mgA and mgB between every pair of chromosomes of rice and Arabidopsis, and applied the largest values (mgA = 160 Kb and mgB = 154 Kb) to all chromosome pairs. The candidate homologous segments can be verified by a statistical test. To check how it affects the scanning process between rice chromosome 1 and Arabidopsis chromosome 1 when using larger mgA and mgB, we found colinear segments with 4 or more collinear gene pairs in 33, out of 1000, simulations.

Application to rice and Arabidopsis

We explored the colinear segments within and between the chromosomes in Arabidopsis and rice. The genomic sequences of Arabidopsis thaliana were from GenBank (Accession NC_003070, NC_003071, NC_003074, NC_003075, NC_003076) [30]. Oryza sativa L. ssp. indica genomic sequences were downloaded from RiceGD [31] and the rice genes were predicted using the software BGF [32] from the Beijing Genome Institute. By performing all-against-all BLASTP, we revealed homologous gene pairs within and between Arabidopsis and rice (BLASTP score > 100).

For Arabidopsis, we searched for the duplication regions with the parameter value r = 4, mg = 116 Kb (~25 intervening genes) and λ = 2.6. We used the maximal mg values estimated between each pairs of Arabidopsis chromosomes. At the significant level of epv <= 0.01, we discovered 203 duplicated sister segments out of 350 candidates, among them 3 were possible perpendicular shadows (Supplementary table 1 [see Additional file 1]). About 75.0% of the genome is in duplicated segments and 22.4%, 1.8% of the genes are in segments with a multiplication level > 2 and > 4, respectively (Table 1). The detected coverage of duplicated regions is a little more than that (71%) found by Blanc et al. [18], less than that (89%) reported by Bowers et al. [33]. The longest sister segments contain 106 colinear genes and extend more than 1.8 Mb in chromosome 2 and 1.55 Mb in chromosome 3 (Table 2). In the longest 20 duplicated segments, 88–100% of the colinear genes are of the same relative transcriptional orientation, indicating a low inversion rate.

Table 1.

The number and percentage of genes in duplicated blocks in rice and Arabidopsis genomes

| Multiplication level 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Arabidopsis | Gene No | 13452 | 3934 | 1345 | 269 | 115 | 86 | 0 |

| Percentage 2 | 0.750 | 0.224 | 0.071 | 0.018 | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.000 | |

| Rice | Gene No | 17947 | 11114 | 6020 | 2930 | 1371 | 846 | 550 |

| Percentage | 0.762 | 0.429 | 0.223 | 0.111 | 0.057 | 0.031 | 0.016 | |

1. Multiplication level of a gene displays that it is in a duplicated segment that appears for how many times in a genome.

2. The percentage is the ratio of genes in multiplication levels >= a specific number.

Table 2.

The 20 longest duplicated segments in the Arabidopsis genome

| Colinear gene number | Gene orientation identity | Epv | Segment A in Arabidopsis | Segment B in Arabidopsis | ||||||

| Starting gene | Ending gene | Gene number | Length (Mb) | Starting gene | Ending gene | Gene number | Length (Mb) | |||

| 106 | 0.96 | 1.92E-226 | 2_3518 | 2_4078 | 560 | 1.88 | 3_4725 | 3_5165 | 440 | 1.55 |

| 83 | 0.96 | 3.99E-200 | 1_1726 | 1_2130 | 404 | 1.54 | 1_6013 | 1_6467 | 454 | 1.65 |

| 82 | 0.98 | 3.64E-199 | 1_6041 | 1_6467 | 426 | 1.56 | 1_1752 | 1_2130 | 378 | 1.45 |

| 78 | 0.97 | 1.83E-155 | 3_840 | 3_1141 | 301 | 0.97 | 5_151 | 5_609 | 458 | 1.54 |

| 70 | 0.90 | 1.38E-138 | 2_3108 | 2_3445 | 337 | 1.26 | 3_4285 | 3_4619 | 334 | 1.19 |

| 69 | 0.97 | 1.68E-129 | 1_3629 | 1_3991 | 362 | 1.43 | 3_1669 | 3_2096 | 427 | 1.56 |

| 64 | 0.94 | 1.23E-116 | 1_639 | 1_343 | 296 | 1.02 | 2_2172 | 2_2582 | 410 | 1.47 |

| 64 | 0.95 | 5.65E-127 | 3_118 | 3_353 | 235 | 0.75 | 5_1391 | 5_1691 | 300 | 1.05 |

| 62 | 1.00 | 2.82E-123 | 1_4258 | 1_4017 | 241 | 0.90 | 3_1328 | 3_1603 | 275 | 0.97 |

| 60 | 0.97 | 1.67E-114 | 4_1800 | 4_1590 | 210 | 0.78 | 5_3789 | 5_4037 | 248 | 0.90 |

| 59 | 0.97 | 1.24E-110 | 2_1607 | 2_1840 | 233 | 0.97 | 4_2963 | 4_3236 | 273 | 1.02 |

| 54 | 0.91 | 9.58E-101 | 4_2685 | 4_2484 | 201 | 0.68 | 5_4682 | 5_5062 | 380 | 1.35 |

| 53 | 0.98 | 6.29E-098 | 2_1326 | 2_1096 | 230 | 0.86 | 4_2727 | 4_2960 | 233 | 0.85 |

| 53 | 0.96 | 3.97E-091 | 3_2507 | 3_2114 | 393 | 1.57 | 4_1114 | 4_1412 | 298 | 1.27 |

| 51 | 0.94 | 6.88E-100 | 2_935 | 2_1093 | 158 | 0.62 | 4_3464 | 4_3625 | 161 | 0.57 |

| 41 | 0.98 | 1.07E-063 | 1_1423 | 1_1285 | 138 | 0.47 | 2_6 | 2_245 | 239 | 0.98 |

| 37 | 0.92 | 3.83E-062 | 2_1308 | 2_1472 | 164 | 0.56 | 4_3786 | 4_3958 | 172 | 0.57 |

| 37 | 0.89 | 1.33E-056 | 4_2327 | 4_2478 | 151 | 0.50 | 5_4245 | 5_4549 | 304 | 1.10 |

| 33 | 0.88 | 1.91E-044 | 1_134 | 1_271 | 137 | 0.44 | 4_191 | 4_396 | 205 | 0.83 |

| 32 | 1.00 | 6.68E-055 | 3_111 | 3_1 | 110 | 0.32 | 5_1250 | 5_1390 | 140 | 0.47 |

* The gene names (also in Table 4 and 5) reflect the chromosome and the gene order, e.g. '2_3518' represents the 3518th gene on chromosome 2.

As for rice, we used another set of parameter values r = 4, mg = 334 Kb (~46 intervening genes) and λ = 3.97. At the same significance level as in Arabidopsis, we revealed 309 duplicated segments out of 841 candidates in rice, among them 13 are possible perpendicular shadows (Supplementary table 2 [see Additional file 2]). In our study we found that 76.2% of the genes were in duplicated regions, significantly higher than 20.59% reported by Simillion et al. [20], also higher than those reported by Paterson et al. [10] (61.9%) and Guyot and Keller [5] (52%). The longest colinear sister regions contain 194 homologous genes and extend more than 4.11 and 3.73 Mb in chromosomes 11 and 12 (Table 3), corresponding a segmental duplication event duplicated ~5–7 Mya [15,34]. About 42.9%, 11.1% of the genome sequences are in a multiplication level of >2 and >4, respectively (Table 1). The transcriptional orientation of colinear genes is in high consistency, similar to that in Arabidopsis. The colinear sister segments at different levels of multiplication are distributed throughout the rice genome.

Table 3.

The 20 longest duplicated segments in the rice genome

| Colinear gene number | Gene orientation identity | Epv | Segment A in rice | Segment B in rice | ||||||

| Starting gene | Ending gene | Gene number | Length (Mb) | Starting gene | Ending gene | Gene number | Length (Mb) | |||

| 194 | 0 | 0.95 | 11_5 | 11_700 | 695 | 4.11 | 12_73 | 12_691 | 618 | 3.73 |

| 191 | 0 | 0.95 | 2_3549 | 2_4505 | 956 | 6.18 | 4_3002 | 4_4139 | 1137 | 7.03 |

| 157 | 0 | 0.94 | 1_5264 | 1_3976 | 1288 | 8.42 | 5_3767 | 5_4423 | 656 | 3.85 |

| 139 | 0 | 0.97 | 1_6225 | 1_5317 | 908 | 5.68 | 5_2981 | 5_3719 | 738 | 4.50 |

| 126 | 3.65E-296 | 0.90 | 8_3168 | 8_4097 | 929 | 5.92 | 9_1944 | 9_2863 | 919 | 5.73 |

| 122 | 8.23E-286 | 0.89 | 3_2952 | 3_1610 | 1342 | 9.01 | 7_3177 | 7_4010 | 833 | 5.10 |

| 110 | 3.85E-257 | 0.94 | 2_5335 | 2_4716 | 619 | 3.94 | 6_682 | 6_1503 | 821 | 5.59 |

| 88 | 5.33E-191 | 0.95 | 2_2758 | 2_3516 | 758 | 5.07 | 4_2121 | 4_2941 | 820 | 5.56 |

| 59 | 2.57E-112 | 0.83 | 3_5355 | 3_5625 | 270 | 1.61 | 7_335 | 7_910 | 575 | 3.87 |

| 41 | 1.81E-067 | 0.98 | 1_743 | 1_1160 | 417 | 2.97 | 5_701 | 5_1067 | 366 | 2.75 |

| 40 | 4.49E-072 | 0.95 | 2_896 | 2_661 | 235 | 1.54 | 6_3717 | 6_4079 | 362 | 2.57 |

| 34 | 4.97E-054 | 0.97 | 3_3955 | 3_4295 | 340 | 2.28 | 12_2686 | 12_2997 | 311 | 2.08 |

| 33 | 1.83E-059 | 0.94 | 2_643 | 2_310 | 333 | 2.22 | 6_4127 | 6_4386 | 259 | 1.64 |

| 32 | 1.30E-051 | 0.94 | 2_1059 | 2_907 | 152 | 1.05 | 6_3325 | 6_3648 | 323 | 2.39 |

| 30 | 8.41E-049 | 0.90 | 2_1361 | 2_1112 | 249 | 1.76 | 6_2904 | 6_3209 | 305 | 2.18 |

| 23 | 1.49E-036 | 0.96 | 3_661 | 3_561 | 100 | 0.59 | 10_1721 | 10_1879 | 158 | 1.16 |

| 22 | 5.24E-030 | 1.00 | 1_6600 | 1_6816 | 216 | 1.30 | 5_2616 | 5_2780 | 164 | 1.15 |

| 22 | 9.83E-031 | 0.95 | 8_2936 | 8_3126 | 190 | 1.40 | 9_1646 | 9_1894 | 248 | 1.80 |

| 21 | 3.50E-038 | 0.95 | 1_581 | 1_724 | 143 | 0.74 | 5_559 | 5_644 | 85 | 0.56 |

| 21 | 3.23E-030 | 0.81 | 3_5157 | 3_5293 | 136 | 0.92 | 7_71 | 7_279 | 208 | 1.32 |

Using parameter values r = 4, mgA = 154 Kb in Arabidopsis, mgB = 160 Kb in rice and λ = 1.47, we found 177 colinear sister segments out of 432 candidates between the chromosomes of two species (Supplementary table 3 [see Additional file 3]), accounting for 32.9% and 16.9% of the Arabidopsis and rice genes, respectively. The longest sister segments are ~0.6 Mb in length and contain ~14 colinear genes, but most segments are much shorter, indicating extensive independent chromosomal rearrangements and gene loss or gain in each genome. The sister copy in rice is always 1–4 times longer than that in Arabidopsis, implying a possible chromosomal expansion in the rice genome (Table 4).

Table 4.

The 20 longest collinear regions between the Arabidopsis and rice genome

| Colinear gene number | Gene orientation identity | epv | Segment in Arabidopsis | Segments in rice | ||||||

| Starting gene | Ending gene | Gene number | Length (Mb) | Starting gene | Ending gene | Gene number | Length (Mb) | |||

| 14 | 0.93 | 5.53E-16 | 4_3648 | 4_3741 | 93 | 0.61 | 2_3736 | 2_3815 | 79 | 0.32 |

| 11 | 0.64 | 1.45E-09 | 2_5222 | 2_5287 | 65 | 0.38 | 4_2954 | 4_3026 | 72 | 0.26 |

| 11 | 0.91 | 2.69E-10 | 4_2502 | 4_2430 | 72 | 0.46 | 2_2835 | 2_2883 | 48 | 0.19 |

| 10 | 0.60 | 1.37E-07 | 7_562 | 7_658 | 96 | 0.64 | 3_2215 | 3_2280 | 65 | 0.24 |

| 10 | 0.70 | 9.51E-08 | 10_3103 | 10_3021 | 82 | 0.54 | 2_3733 | 2_3781 | 48 | 0.19 |

| 10 | 0.70 | 3.61E-09 | 1_5674 | 1_5595 | 79 | 0.51 | 2_3286 | 2_3339 | 53 | 0.18 |

| 10 | 0.90 | 4.37E-10 | 8_3510 | 8_3590 | 80 | 0.42 | 5_4866 | 5_4931 | 65 | 0.23 |

| 9 | 0.78 | 7.81E-07 | 3_1660 | 3_1736 | 76 | 0.48 | 2_2221 | 2_2248 | 27 | 0.12 |

| 9 | 0.89 | 3.63E-07 | 2_4713 | 2_4635 | 78 | 0.41 | 5_4870 | 5_4948 | 78 | 0.29 |

| 9 | 0.56 | 4.60E-08 | 9_2767 | 9_2822 | 55 | 0.31 | 4_3435 | 4_3468 | 33 | 0.12 |

| 9 | 0.89 | 1.44E-08 | 7_3347 | 7_3305 | 42 | 0.28 | 1_5880 | 1_5908 | 28 | 0.10 |

| 9 | 1.00 | 4.51E-10 | 1_5843 | 1_5889 | 46 | 0.31 | 3_4249 | 3_4279 | 30 | 0.10 |

| 8 | 0.75 | 1.32E-05 | 5_3294 | 5_3386 | 92 | 0.56 | 5_104 | 5_198 | 94 | 0.29 |

| 8 | 0.75 | 6.45E-05 | 6_1100 | 6_1031 | 69 | 0.54 | 5_5811 | 5_5863 | 52 | 0.21 |

| 8 | 0.75 | 6.08E-05 | 7_3242 | 7_3189 | 53 | 0.32 | 5_5408 | 5_5441 | 33 | 0.12 |

| 8 | 0.75 | 4.70E-05 | 4_2502 | 4_2430 | 72 | 0.46 | 3_4109 | 3_4154 | 45 | 0.16 |

| 8 | 0.75 | 3.60E-05 | 4_3665 | 4_3741 | 76 | 0.50 | 3_4887 | 3_4952 | 65 | 0.23 |

| 8 | 0.63 | 2.24E-05 | 6_772 | 6_682 | 90 | 0.57 | 4_3081 | 4_3144 | 63 | 0.21 |

| 8 | 0.63 | 1.25E-05 | 4_2498 | 4_2425 | 73 | 0.49 | 2_1946 | 2_2009 | 63 | 0.19 |

| 8 | 0.63 | 1.12E-05 | 1_5796 | 1_5720 | 76 | 0.43 | 5_128 | 5_207 | 79 | 0.25 |

Discussion

Identification of the duplicated segments, especially their distribution pattern in a genome, is essential for further inference on when and how the duplication or species divergence occurred, and whether or not recurrent duplication events happened. The selection of parameter values, in particular the maximum gap length between the neighboring genes, is critical to detect chromosomal homology. However, the selection of maximum gap length in previous reported studies was mainly empirical, which might fail to detect authentic duplicated segments [20,22,23]. Many fewer and shorter duplicated segments are discovered when a smaller gap length is adopted, such as in the case of rice [20], whereas more and longer duplicated regions can be found if a larger gap length is adopted. Moreover, different gap length should be used in different genomes such as Arabidopsis and rice, since the density of colinear genes varies due to DNA loss and insertion. By considering the difference in gene density, especially the density of homologous genes in different genomes, we determined the maximum gap length based on statistical analysis. For example, when the duplicated regions in Arabidopsis and rice are detected, the maximum gap lengths were estimated to be 116 Kb and 334 Kb, respectively.

The input data of our approach can be any type of genetic markers such as sequences, genetic markers. Various measurements can be used to represent the distance between markers, such as physical or genetic distances, or gene numbers. In most previous studies, the significance of the predicted colinear regions was evaluated by a permutation test, which is rather time-consuming [20,23]. We estimate the significance of the predicted colinear segments through statistical inference. The statistical inference has the advantage over the permutation test in terms of computational efficiency. It takes only 2 minutes to calculate the epv to evaluate their significance on a personal computer (AMD AthlonXP 2000+, 512 MB RAM) while running a permutation test takes several hours on the same machine. The massive gene duplications and translocations in its proximal regions will lead to many colinearity shadows, decreasing the computational efficiency. We include a neighborhood masking procedure in ColinearScan to remove colinearity shadows in our algorithm, which dramatically improves the efficiency of detecting duplicated segments in the rice genome.

ADHoRe adopts linear regression analysis to infer duplicated chromosomal segments [20,21]. The underlying assumption is that gene loss rates have been balanced between sister segments, resulting in a straight line in the dot map. The colinear homologues in a chromosomal segment might be interspersed by individual genes that have no homologues at the corresponding position in its sister segment. At the very beginning of divergence of the sister segments, there should be one-to-one gene homology. Thereafter, massive gene deletions, translocations and chromosomal rearrangements occur and the initial pattern eventually becomes obscured [25]. The homologues with the conservative orders would appear in a straight line in the dot map if gene deletion or insertion had been balanced in different regions of the sister segments, otherwise in a curvy line. Wang et al. [15] explore the gene loss rates in the sister segments in rice and find that nearly straight lines are obtained for some sister segments, e.g., in chromosomes 11 and 12, and in chromosomes 2 and 4. However, curvy lines are also found for some sister segments, e.g., in chromosomes 1 and 5, and in chromosomes 8 and 9. A linearity assumption might fail to detect true duplicated segments. In FISH, Calabrese et al. [24] also adopt a colinearity strategy and develop a different statistical approach to evaluate the extension of collinear points, referred as clump in GHM. However, the value of key parameter p, reflecting the probability that a point occurs in the neighborhood of the former point, is artificially defined, and the maximal gap is deduced from p in their approach. DiagHunter [25] adopts a colinearity method similar to our approach, and the maximal length of the path is predefined. The program stops extending the current path until it reaches the maximal length threshold, or other neighboring points cannot be found.

Polyploidy has been supposed to be prevalent in plants. Recently, genome-wide studies further suggest the ubiquity of polyploidy, even in genomes which have not been considered to undergo genomic duplication [35]. The small genome of Arabidopsis has been reported to have undergone at least one round of duplication by different groups [12,18]. Here using a different method, we discover that 75.0% of the Arabidopsis genome sequences are in duplicated regions and a significant portion of sequences have multiple copies. The previous studies in the rice genome have been focused on the large obvious duplicated segments, produced by the relatively recent duplication events [15,36]. Here, we detect 76.2% of rice sequences in duplicated regions, and 42.9% have multiple copies.

The possibility of constructing the monocot-dicot comparative genetic map has been discussed [37] based on the comparison of Arabidopsis and rice sequences [38,39]. However, a comprehensive detection of homologous regions between these two genomes has not been available. Based on gene colinearity, we detected homologous regions between Arabidopsis and rice, accounting for 32.9% and 16.9% of each genome. All homologous segments were shorter than 0.6 Mb in length, indicating the massive genome rearrangements in both genomes after the monocot-dicot divergence. Though the short homologous segments make it difficult to construct the comparative genetic map between monocot and dicot, the homologues in colinearity found in this study may provide clues for further work in comparative genomics.

Conclusion

We develop an algorithm to detect homologous chromosomal segments with conserved gene order, and we propose a statistical approach to estimate parameters and evaluate the significance of potential homology. We apply this approach to rice and Arabidopsis with high efficiency to detect potential colinear regions and evaluate their significance. We find many more homologous chromosomal segments in rice genomes than previously reported, which consolidated the inference that a polyploidy had occurred in the common ancestor of grasses. We also find many small colinear segments between rice and Arabidopsis genomes, providing clues to the evolutionary history of monocots and dicots.

Authors' contributions

XW and XS developed the algorithm and the statistical models under the supervision of JL. XW, XS and ZL implemented the programs in rice and Arabidopsis, QZ and SG contributed to this work on plant biology and evolution, ZL and LK developed the online web server, WT provided technical support to the project. All the authors contributed to the refinement of the manuscript drafted by XW.

Availability and requirements

• Project name: ColinearScan

• Project home page: http://colinear.cbi.pku.edu.cn

• Operating systems: Linux, Unix

• Programming languages: C++, PERL

• Other requirements: Standard C++ Library, BioPerl and other PERL modules including Getopt::Long and Pod::Usage

• License: GPL

Supplementary Material

Colinear blocks in Arabidopsis. A list of all collinear blocks in Arabidopsis

Colinear blocks in rice. A list of all collinear blocks in rice

Colinear blocks between rice and Arabidopsis. A list of all collinear blocks between rice and Arabidopsis

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Manyuan Long, Wentian Li, Liping Wei, Min Zhao, Ge Gao, Di Liu for helpful discussions. This study was supported by the National Key Basic Research Program of China (973 No 2003CB715900), Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, No 90408015 and 30170232) and the China High-tech Program, the China High Technology Platform and the Program of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities, no. B06001.

Contributor Information

Xiyin Wang, Email: wangxy@mail.cbi.pku.edu.cn.

Xiaoli Shi, Email: shixl@mail.cbi.pku.edu.cn.

Zhe Li, Email: liz@mail.cbi.pku.edu.cn.

Qihui Zhu, Email: zhuqh@mail.cbi.pku.edu.cn.

Lei Kong, Email: kongl@mail.cbi.pku.edu.cn.

Wen Tang, Email: tangw@mail.cbi.pku.edu.cn.

Song Ge, Email: gesong@ibcas.ac.cn.

Jingchu Luo, Email: luojc@pku.edu.cn.

References

- Devos KM, Gale MD. Genome relationships: the grass model in current research. Plant Cell. 2000;12:637–646. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.5.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourque G, Sankoff D. Improving gene network inference by comparing expression time-series across species, developmental stages or tissues. J Bioinform Comput Biol. 2004;2:765–783. doi: 10.1142/S0219720004000892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellis M, Birren BW, Lander ES. Proof and evolutionary analysis of ancient genome duplication in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2004;428:617–624. doi: 10.1038/nature02424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoffels A, Koh EG, Chia JM, Brenner S, Aparicio S, Venkatesh B. Fugu genome analysis provides evidence for a whole-genome duplication early during the evolution of ray-finned fishes. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:1146–1151. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyot R, Keller B. Ancetral genome duplication in rice. Genome. 2004;47:610–614. doi: 10.1139/g04-016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaillon O, Aury JM, Brunet F, Petit JL, Stange-Thomann N, Mauceli E, Bouneau L, Fischer C, Ozouf-Costaz C, Bernot A, Nicaud S, Jaffe D, Fisher S, Lutfalla G, Dossat C, Segurens B, Dasilva C, Salanoubat M, Levy M, Boudet N, Castellano S, Anthouard V, Jubin C, Castelli V, Katinka M, Vacherie B, Biemont C, Skalli Z, Cattolico L, Poulain J, De Berardinis V, Cruaud C, Duprat S, Brottier P, Coutanceau JP, Gouzy J, Parra G, Lardier G, Chapple C, McKernan KJ, McEwan P, Bosak S, Kellis M, Volff JN, Guigo R, Zody MC, Mesirov J, Lindblad-Toh K, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Kahn D, Robinson-Rechavi M, Laudet V, Schachter V, Quetier F, Saurin W, Scarpelli C, Wincker P, Lander ES, Weissenbach J, Roest Crollius H. Genome duplication in the teleost fish Tetraodon nigroviridis reveals the early vertebrate proto-karyotype. Nature. 2004;431:946–957. doi: 10.1038/nature03025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koszul R, Caburet S, Dujon B, Fischer G. Eucaryotic genome evolution through the spontaneous duplication of large chromosomal segments. Embo J. 2004;23:234–243. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seoighe C, Gehring C. Genome duplication led to highly selective expansion of the Arabidopsis thaliana proteome. Trends Genet. 2004;20:461–464. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Lu HH, Chung WY, Yang J, Li WH. Patterns of Segmental Duplication in the Human Genome. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:135–141. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson AH, Bowers JE, Chapman BA. Ancient polyploidization predating divergence of the cereals, and its consequences for comparative genomics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9903–9908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307901101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raes J, Vandepoele K, Simillion C, Saeys Y, Van de Peer Y. Investigating ancient duplication events in the Arabidopsis genome. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2003;3:117–129. doi: 10.1023/A:1022666020026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simillion C, Vandepoele K, Van Montagu MC, Zabeau M, Van de Peer Y. The hidden duplication past of Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13627–13632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212522399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetzen JL, Ramakrishna W. Numerous small rearrangements of gene content, order and orientation differentiate grass genomes. Plant MolBiol. 2002;48:821–827. doi: 10.1023/A:1014841515249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan H, Levy AA, Feldman M. Allopolyploidy-induced rapid genome evolution in the wheat (Aegilops-Triticum) group. Plant Cell. 2001;13:1735–1747. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.8.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Shi X, Hao B, Ge S, Luo J. Duplication and DNA segmental loss in the rice genome: implications for diploidization. New Phytologist. 2005;165:937–946. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Peer Y. Computational approaches to unveiling ancient genome duplications. Nature review genetics. 2004;5:752–763. doi: 10.1038/nrg1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaut BS. Patterns of chromosomal duplication in maize and their implications for comparative maps of the grasses. Genome Res. 2001;11:55–66. doi: 10.1101/gr.160601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc G, Hokamp K, Wolfe KH. A recent polyploidy superimposed on older large-scale duplications in the Arabidopsis genome. Genome Res. 2003;13:137–144. doi: 10.1101/gr.751803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLysaght A, Hokamp K, Wolfe KH. Extensive genomic duplication during early chordate evolution. Nat Genet. 2002;31:200–204. doi: 10.1038/ng884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simillion C, Vandepoele K, Van de Peer Y. Recent developments in computational approaches for uncovering genomic homology. Bioessays. 2004;26:1225–1235. doi: 10.1002/bies.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandepoele K, Saeys Y, Simillion C, Raes J, Van De Peer Y. The automatic detection of homologous regions (ADHoRe) and its application to microcolinearity between Arabidopsis and rice. Genome Res. 2002;12:1792–1801. doi: 10.1101/gr.400202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vision TJ, Brown DG, Tanksley SD. The origins of genomic duplications in Arabidopsis. Science. 2000;290:2114–2117. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5499.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe KH, Shields DC. Molecular evidence for an ancient duplication of the entire yeast genome. Nature. 1997;387:708–713. doi: 10.1038/42711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese PPCSVTJ. Fast identificatin and statistical evalution of segmental homologies in comparative maps. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:i74–i80. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon SBKACBMRYND. DiagHunter and GenoPix2D: programs for genomic comparisons, large-scale homology discovery and visualization. Genome Biology. 2003;4 doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-10-r68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandepoele K, Simillion C, Van de PY. Evidence that rice and other cereals are ancient aneuploids. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2192–2202. doi: 10.1105/tpc.014019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe KH, Gouy M, Yang YW, Sharp PM, Li WH. Date of the monocot-dicot divergence estimated from chloroplast DNA sequence data. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:6201–6205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.16.6201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TFWMS. Identification of common molecular subsequences. J Mol Biol. 1981;147:195–197. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GenBank [www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/]

- RiceGD [http://btn.genomics.org.cn]

- Heng Li JSLZXJJLFLGYDLZXXSGGTLHHLYLLJFHMXWMZBLH. Test Data Sets and Evaluation of Gene Prediction Programs on the Rice Genome. J Comput Sci Technol. 2005;20:446–453. doi: 10.1007/s11390-005-0446-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers JE, Chapman BA, Rong J, Paterson AH. Unravelling angiosperm genome evolution by phylogenetic analysis of chromosomal duplication events. Nature. 2003;422:433–438. doi: 10.1038/nature01521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Rice Chromosomes 11 and 12 Sequencing Consortia The sequence of rice chromosomes 11 and 12, rice in disease resistance genes and recent gene duplications. BMC Biology. 2005;3:20. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-3-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis PS. Ancient and recent polyploidy in angiosperms. New Phytol. 2005;166:5–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson AH, Bowers JE, Van de Peer Y, Vandepoele K. Ancient duplication of cereal genomes. New Phytol. 2005;165:658–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson AH, Lan TH, Reischmann KP, Chang C, Lin YR, Liu SC, Burow MD, Kowalski SP, Katsar CS, DelMonte TA, Feldmann KA, Schertz KF, Wendel JF. Toward a unified genetic map of higher plants, transcending the monocot-dicot divergence. Nat Genet. 1996;14:380–382. doi: 10.1038/ng1296-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff SA, Ricke D, Lan TH, Presting G, Wang R, Dunn M, Glazebrook J, Sessions A, Oeller P, Varma H, Hadley D, Hutchison D, Martin C, Katagiri F, Lange BM, Moughamer T, Xia Y, Budworth P, Zhong J, Miguel T, Paszkowski U, Zhang S, Colbert M, Sun WL, Chen L, Cooper B, Park S, Wood TC, Mao L, Quail P, Wing R, Dean R, Yu Y, Zharkikh A, Shen R, Sahasrabudhe S, Thomas A, Cannings R, Gutin A, Pruss D, Reid J, Tavtigian S, Mitchell J, Eldredge G, Scholl T, Miller RM, Bhatnagar S, Adey N, Rubano T, Tusneem N, Robinson R, Feldhaus J, Macalma T, Oliphant A, Briggs S. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica) Science. 2002;296:92–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Sachidanandam R, Stein L. Comparative genomics between rice and Arabidopsis shows scant collinearity in gene order. Genome Res. 2001;11:2020–2026. doi: 10.1101/gr.194501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Colinear blocks in Arabidopsis. A list of all collinear blocks in Arabidopsis

Colinear blocks in rice. A list of all collinear blocks in rice

Colinear blocks between rice and Arabidopsis. A list of all collinear blocks between rice and Arabidopsis