Abstract

The Tc1/mariner transposable element superfamily is widely distributed in animal and plant genomes. However, no active plant element has been previously identified. Nearly identical copies of a rice (Oryza sativa) Tc1/mariner element called Osmar5 in the genome suggested potential activity. Previous studies revealed that Osmar5 encoded a protein that bound specifically to its own ends. In this report, we show that Osmar5 is an active transposable element by demonstrating that expression of its coding sequence in yeast promotes the excision of a nonautonomous Osmar5 element located in a reporter construct. Element excision produces transposon footprints, whereas element reinsertion occurs at TA dinucleotides that were either tightly linked or unlinked to the excision site. Several site-directed mutations in the transposase abolished activity, whereas mutations in the transposase binding site prevented transposition of the nonautonomous element from the reporter construct. This report of an active plant Tc1/mariner in yeast will provide a foundation for future comparative analyses of animal and plant elements in addition to making a new wide host range transposable element available for plant gene tagging.

INTRODUCTION

The Tc1/mariner superfamily contains transposable elements from diverse taxa, including fungi, flies, nematodes, fishes, and mammals (Plasterk and van Luenen, 2002). These elements share three characteristics: a target site duplication (TSD) of the dinucleotide TA, a transposase with a DDE/D catalytic motif (the active site where divalent cations bind), and short terminal inverted repeats (TIRs) of related sequences. Variation in the DDE/D signature led to the placement of Tc1/mariner elements into six monophyletic groups: DD34E, DD34D, DD37D, DD37E, DD31-33D, and DD35E (Doak et al., 1994; Capy et al., 1998; Robertson et al., 1998; Plasterk et al., 1999; Shao and Tu, 2001). Although two plant Tc1/mariner elements were identified from soybean (Glycine max) (Soymar1) and rice (Oryza sativa) (later named Osmar1), it was not until the design of plant-specific PCR primers that related elements were found to be widespread in plant genomes and to compose a seventh monophyletic group (DD39D) (Jarvik and Lark, 1998; Tarchini et al., 2000; Feschotte and Wessler, 2002; Feschotte et al., 2003; Jacobs et al., 2004).

Mutational analysis of various Tc1/mariner transposases confirmed the critical role of the DDE/D motif and has provided evidence that an intact DNA binding domain (DBD) is also required for activity. Mutations in the DD34E motifs of Tc1 and Tc3 abolished transposase activity in vitro (van Luenen et al., 1994; Vos and Plasterk, 1994). Furthermore, the crystal structure of the Mos1 catalytic domain suggests an interaction between its DD34D motif and divalent cations (Mg2+ or Mn2+) (Richardson et al., 2006). The Tc1/mariner transposases also contain helix-turn-helix (HTH) motifs that are required for its binding to TIRs, the first step of transposition (Lampe et al., 1996; van Pouderoyen et al., 1997; Wang et al., 1999; Auge-Gouillou et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2001; Izsvak et al., 2002; Watkins et al., 2004).

To date, activity has been demonstrated for seven naturally occurring Tc1/mariner elements: Tc1 and Tc3 from Caenorhabditis elegans (Emmons et al., 1983; Collins et al., 1989); Minos, Mos1, and Himar1 from flies (Bryan et al., 1990; Franz and Savakis, 1991; Robertson and Lampe, 1995), and Impala and Fot1 from the fungus Fusarium oxysporum (Daboussi et al., 1992; Langin et al., 1995). Although superfamily members are widespread in vertebrate genomes, no active elements have been isolated to date. Instead, two active transposases were phylogenetically reconstructed from nonfunctional vertebrate elements: Sleeping Beauty from eight fish species and Frog Prince from Rana pipiens (frog) (Ivics et al., 1997; Miskey et al., 2003). Both reconstructed elements transpose in a variety of vertebrates, including primates, and, as such, have been developed into valuable tools for human gene discovery (Yant et al., 2000; Davidson et al., 2003; Miskey et al., 2003; Ivics and Izsvak, 2004; Dupuy et al., 2005; Starr and Largaespada, 2005).

The availability of sequence from most of the genomes of two subspecies of rice, indica and japonica, facilitated a computer-assisted survey that identified 34 Tc1/mariner elements belonging to 25 subfamilies (Feschotte et al., 2003). Seven of the 34 elements (Osmar1A, Osmar5A, Osmar5Bi, Osmar9A, Osmar15Bi, Osmar17A, and Osmar19) encode potentially functional transposases with no interrupting stop codons. Among these, Osmar5 was chosen as the best candidate for an active element because virtually identical copies were present in japonica (one copy) and indica (two copies; one full length and one truncated) at different genomic loci. In a previous study, binding of the Osmar5 transposase to its TIRs was demonstrated in a yeast one-hybrid assay in which the protein bound specifically to copies of the TIR on a reporter construct. Specific binding was also demonstrated in vitro using a fusion protein synthesized in Escherichia coli and DNA fragments from the ends of Osmar5. The first 206 residues of Osmar5 transposase, which contain two HTH motifs (Figure 1), were shown to bind specifically to two sequence motifs that comprise a 17-bp region of the TIR (called Box1 and Box2; Figure 1). An additional copy of the 17-bp binding site adjacent to the 3′ TIR also binds transposase (Feschotte et al., 2005).

Figure 1.

Scheme of Osmar5, the Osmar5 Transposase Coding Sequence (Osmar5 Transposase), and the Nonautonomous Element (Osmar5NA).

TIRs are shown as black triangles. White boxes represent Osmar5 coding exons, and shaded regions represent noncoding sequences; slashed regions indicate introns. The dark region in Osmar5NA represents the linker sequence (see Methods). The NdeI site used for ADE2 revertant plasmid digestion is also shown. HTH1 and HTH2 represent helix-turn-helix motifs 1 and 2, respectively. Box1 and Box2 indicate transposase binding site motifs. The three Asp residues (D242, D365, and D405) constitute the putative DD39D motif.

In this study, we have again used a yeast assay, but here to test for Osmar5 transposition, including excision and reinsertion. We turned to a yeast assay for two reasons. First, previous studies indicated that transposition of Tc1/mariner elements (e.g., Himar1, Mos1, and Tc1) could occur without host-specific factors (Lampe et al., 1996; Vos et al., 1996; Tosi and Beverley, 2000). That is, members of this superfamily transpose in organisms as diverse as bacteria and human (Ivics et al., 1997; Rubin et al., 1999). The second reason for turning to yeast is that it was shown previously to support transposition of the maize Ac and Ds elements (Weil and Kunze, 2000). Here, we report that the rice Osmar5 element transposes in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Analysis of transposon footprints at the excision site suggests a model for how the transposase cleaves this site to promote element transposition. In addition, new insertions of Osmar5 into TA dinucleotides were detected in the vector and in yeast chromosomes. Finally, transposition was reduced or prevented by mutation of the DD39D catalytic domain and by either deletion of the transposase DBD or mutation of the TIR binding site.

RESULTS

Yeast Transposition Assay

A yeast assay was devised to determine whether Osmar5 encoded an active transposase and, if so, the features of excision and reinsertion. The assay involved two constructs, one encoding the transposase source and the other a reporter for excision. The transposase source, pOsm5Tp, has Osmar5 coding sequence (Figure 1) fused to the inducible gal1 promoter and contains his3 as a selectable marker (Figure 2). The reporter construct, pOsm5NA, contains a nonautonomous Osmar5 element (Osmar5NA) (Figure 1) inserted in the 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR) of an ade2 reporter gene with ura3 as a selectable marker (Figure 2). To prevent the repair of excision sites by the very efficient yeast homologous recombination system, a haploid yeast strain was used as recipient (DG2523; see Methods) in addition to including ARS1/CEN4 in the plasmid reporter construct (pOsm5NA), so that it was maintained as a single copy in yeast (Falcon and Aris, 2003).

Figure 2.

Yeast Transposition Assay Constructs and Protocol.

The positions of primers used for PCR analysis in Figure 3B are shown as gray arrows. amp, ampicillin resistance gene; ARS1, autonomous replication sequence1; ARS H4, autonomous replication sequence of the H4 gene; CEN6 and CEN4, centromere sequences of yeast chromosomes 6 and 4, respectively; cyc1 ter, terminator of yeast cyclin gene cyc1; OriEC, E. coli replication origin; Pgal1, yeast gal1 promoter; pRS413, control vector like pOsm5Tp but without the transposase. See Methods and text for details.

Transformants containing both plasmids were selected on plates containing 2% galactose and 1% raffinose but lacking histidine and uracil. Colonies were picked from plates containing the double transformants, and ADE2 revertants were selected based on growth on agar plates without adenine. Excision events were confirmed by PCR amplification of the ade2 5′ UTR and subsequent sequencing (Figure 2, see primer location). Finally, as a control, we used plasmid pRS413, which is identical to pOsm5Tp except that it lacks the Pgal1-Osmar5 transposase gene.

Excision of Osmar5NA

Double transformants containing pOsm5Tp (or control plasmid pRS413) and pOsm5NA were streaked onto plates lacking adenine to select for ADE2 revertants. Many ADE2 revertant colonies were obtained for pOsm5Tp, but none were obtained for control plasmid pRS413 (Figure 3A). Plasmid DNA was prepared from ADE2 revertants, and excision of the Osmar5NA element from the reporter construct was confirmed by PCR amplification using primers flanking the element insertion site on pOsm5NA (Figure 3B). Sequencing of this locus from independent ADE2 revertants revealed that excision of Osmar5NA was accompanied by the formation of many and diverse transposon footprints (Figure 3C). Compared with this locus in the original plasmid (Figure 3C, pOsm5NA, boxed region), all but one of the plasmids from ADE2 revertant colonies had the TA duplication intact but also contained between one and seven additional nucleotides that appeared to be derived from the ends of Osmar5NA. For all of these excision events, none had what would be equivalent to a precise excision, that being the removal of the entire element and one copy of the dinucleotide TA from the TSD (see Discussion).

Figure 3.

Osmar5NA Footprints.

(A) ADE2 revertants on medium lacking adenine. The left two sectors show single colonies derived from two independent pOsm5Tp and pOsm5NA double transformant colonies. Sectors at right are from pRS413 and pOsm5NA double transformant colonies.

(B) Agarose gel of PCR products from the ade2 5′ UTR of the ADE2 revertant plasmids. Expected band size is 1.4 or 0.4 kb (control), with or without Osmar5NA, respectively.

(C) Sequences of excision sites of ADE2 revertants. Part of the sequence of pOsm5NA before excision is shown at top, including the ends of Osmar5NA (boxed) and flanking sequence. The dinucleotides TA that flank Osmar5 in the donor vector and in each footprint are shown in red.

Reinsertion of Osmar5NA

Transposition involves both excision and reinsertion of the excised element into a new locus. To understand the fate of the excised Osmar5NA, DNA extracted from eight independent ADE2 revertants was used for DNA gel blot analysis. To this end, the DNAs were digested with DraI (which does not cut in Osmar5NA), and the resultant DNA gel blot was probed with labeled Osmar5NA (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Genomic DNA Gel Blot Analysis of ADE2 Revertants.

Genomic DNA (from eight independent revertants, labeled 1 to 8) was digested with DraI, and blots were probed with Osmar5NA. Controls are untransformed yeast (DG2523) and pOsm5NA. Two minor bands in the vector control and revertant lanes are attributable to nonspecific cleavage by DraI. DNA size markers at left are in kilobases.

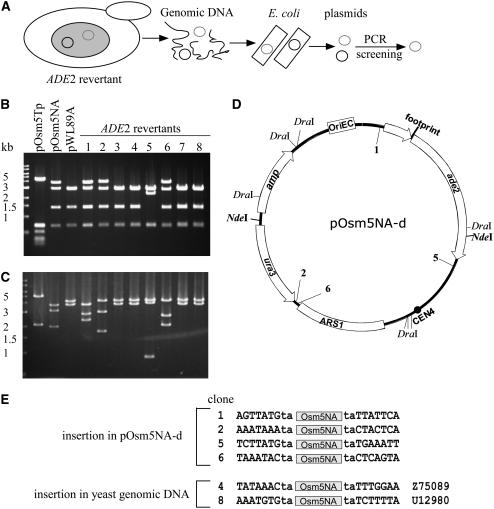

Compared with the plasmid control (Figure 4, pOsm5NA), new bands were visualized in samples 1, 4, 5, and 8, suggesting insertion of Osmar5NA at new loci. However, because samples 2, 3, 6, and 7 contained a single band that comigrated with the plasmid control, as does one of the two bands in sample 1, we reexamined the presumptive excision sites in these strains. For each strain, sequenced PCR products revealed a transposon footprint in place of the Osmar5NA element (data not shown). Based on these results, we hypothesized that in each strain, the Osmar5NA element had transposed to new sites in the pOsm5NA vector. To test this hypothesis, DNAs isolated from each strain were used to transform E. coli and recover their plasmids. Because the DNA samples contained both pOsm5Tp and pOsm5NA, PCR amplification of the ade2 5′ UTRs of the recovered plasmids was performed to screen for plasmids containing the ade2 gene (in the plasmid derivatives of pOsm5NA) (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Reintegration Sites of Osmar5NA.

(A) Scheme of plasmid rescue from ADE2 revertant genomic DNA. Yeast genomic DNA was extracted from ADE2 revertants and used to transform E. coli (see text for details). The small gray and black circles represent pOsm5NA and pOsm5Tp, respectively.

(B) Agarose gel analysis of DraI digestion of the recovered pOsm5NA derivative plasmids from (A). DNA size markers are shown at left.

(C) NdeI digestion of the plasmids used for (B).

(D) Insertion sites in pOsm5NA derivatives (pOsm5NA-d); pWL89A lacks Osmar5NA. Note that Osmar5NA has a NdeI site but not a DraI site.

(E) Insertion sites of ADE2 revertants in either the plasmid vector or yeast genomic DNA. Accession numbers of yeast genomic DNA are shown at right.

Reinsertion sites of Osmar5NA in the excision derivatives of pOsm5NA (called pOsm5NA-d) were analyzed by comparing their restriction digestion patterns with those of control plasmids after digestion with DraI (Figure 5B) and NdeI (Figure 5C). Four of the eight plasmids (Figures 5B and 5C, lanes 1, 2, 5, and 6) have an altered pattern from that of pWL89A (otherwise identical to pOsm5NA except lacking Osmar5NA), suggesting that Osmar5NA had reinserted into the plasmid after excision. The putative insertion sites in pOsm5NA-d plasmids were approximated by analysis of the restriction digests with DraI and NdeI (data not shown). Once the approximate location of the reinserted element was known, sequencing primers were designed to determine precise insertion sites of Osmar5NA in the vector (Figure 5D). All four had inserted at TA dinucleotides and generated TSDs upon insertion (Figure 5E). The fact that all insertion sites were intergenic suggests that the majority of insertions may have been eliminated by selection for plasmid functions.

The remaining four plasmids (Figures 5B and 5C, lanes 3, 4, 7, and 8) have an identical pattern to that of pWL89A, indicating the absence of Osmar5NA in the vector and the possibility that the element had transposed into a yeast chromosome. For these strains, insertion sites in the yeast genome were determined by performing inverse PCR with primers located near the Osmar5NA termini, with their 3′ ends to be extended outward into presumed flanking yeast genomic DNA (see Methods). PCR products were successfully obtained for two samples (lanes 4 and 8 in Figure 4; data not shown), and BLAST searches of the resultant sequences led to the identification of insertion sites of Osmar5NA in the yeast genome (Figure 5E).

Mutagenesis Analysis of Osmar5 Transposase and Transposon TIRs

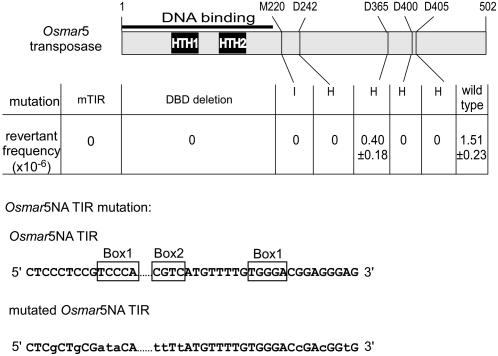

In a previous study, the putative transposase peptide sequences for 34 Osmar elements were aligned with that of Soymar1 to identify conserved residues (Feschotte et al., 2003). Highly conserved sites include Met-220, which is located at the junction of the DBD and the catalytic domain, and the predicted DD39D motif (Asp-242, Asp-365, Asp-405). Interestingly, Asp-400, which is 34 residues from Asp-365, is also well conserved (94% identity). To evaluate the importance of these conserved sites for transposition, site-directed mutagenesis was performed. Mutation of Met-220 to Ile and Asp-242, Asp-400, Asp-405 to His abolished activity, as no ADE2 revertants were obtained in the excision assay (Figure 6). However, mutation of Asp-365 to His reduced the ADE2 revertant frequency to approximately one-fourth (0.40 × 10−6/cell) of that of intact Osmar5 transposase (1.51 × 10−6/cell). These results suggest that the putative DD39D motif, as well as the conserved Met-220 and Asp-400 motifs, are important for efficient transposition activity.

Figure 6.

Mutations Introduced in the Transposase and TIR and Their Effect on Transposition.

Vectors containing the intact Osmar5 transposase gene (wild type) and its mutated forms were cotransformed with pOsm5NA, and double transformants were selected for ADE2 reversion. mTIR, mutated TIR of Osmar5NA; DBD deletion, DNA binding domain deletion; M220→I, Met at position 220 mutated to Ile; D242→H, Asp at position 242 mutated to His; D365→H, Asp at position 365 mutated to His; D400→H, Asp at position 400 mutated to His; D405→H, Asp at position 405 mutated to His. Standard errors for six independent events are shown. The nucleotide changes in the Osmar5NA TIRs are shown in lowercase letters. Dots represent omitted internal sequences of Osmar5NA. Previously identified DNA binding motifs are shown in boxes.

To test whether interaction between Osmar5 TIRs and transposase DBDs is required for transposition, site-directed mutagenesis of Osmar5NA was performed so that the TIRs contained mutations in the strictly conserved (>99% identity among 34 Osmar elements) terminal sequence CTCCCTCC as well as in the two previously identified motif boxes of the TIRs (Figure 6) (Feschotte et al., 2005). When a derivative of pOsm5NA containing mutated Osmar5NA TIRs was used in the excision assay with pOsm5Tp, no ADE2 revertants were obtained, indicating that transposition of Osmar5 requires correct TIR sequences. Similarly, no ADE2 revertants were obtained when the DBD of Osmar5 transposase was deleted (Figure 6). These results suggest that both functional TIRs and transposase DBDs are required for transposition.

DISCUSSION

The Tc1/mariner superfamily is widespread and well characterized in eukaryotic genomes. However, although it is also widespread in the genomes of flowering plants, no active elements have been reported. In this study, we demonstrate that the rice Osmar5 element encodes a transposase that catalyzes the excision and reinsertion of a nonautonomous derivative element in yeast. Because the catalytic domains of plant Tc1/mariner elements form a distinct monophyletic clade, it was of interest to initiate a comparative analysis of the catalytic properties of plant and animal elements. In addition, as discussed in more detail below, Tc1/mariner elements are thought to furnish the transposase for the movement of the nonautonomous Stowaway miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs) (Feschotte and Mouches, 2000; Feschotte et al., 2003). Stowaway MITEs are present in thousands of copies in the genomes of many plant species, where they are particularly enriched in the noncoding regions of genes (Bureau and Wessler, 1994; Turcotte et al., 2001; Schenke et al., 2003). To date, no actively transposing Stowaway elements have been identified. As such, the availability of an active plant Tc1/mariner element provides an opportunity to analyze the amplification of Stowaway MITEs and their contribution to the evolution of plant genomes.

Tc1/Mariner Element Transposition: Plants versus Animals

A transposition mechanism for Tc1/mariner elements was originally proposed based on in vivo and in vitro analysis of Tc3 from C. elegans (van Luenen et al., 1994), whereby transposition occurs in several steps: (1) transposase binds to the element TIR through its bipartite DBD; (2) the catalytic domain mediates element excision by cleavage at two sites, two nucleotides inside the 5′ ends and precisely at the 3′ junction between the TSD and the element ends (Figure 7); cleavage results in excision sites (and excised elements) with two-nucleotide protruding 3′ ends; (3) excised elements exist as free circular intermediates that target TA dinucleotides for insertion; (4) the 3′ hydroxyl group initiates nucleophilic attack at a TA dinucleotide, producing a staggered cut; (5) element integration is accompanied by DNA synthesis, which repairs the gaps and generates the TSD; and (6) host repair of the excision site, creating transposon footprints. This model was also shown to hold for Tc1 and Himar1 (Radice and Emmons, 1993; Lipkow et al., 2004).

Figure 7.

Representative Footprints for Tc3, Mos1, Minos, and Osmar5NA.

Donor sites are shown as double stranded, but footprints are shown as single strands (top strand). TSDs are shown in red. Lowercase letters indicate residues retained from transposon ends. Arrows indicate proven (Tc3 and Mos1) or predicted (Minos and Osmar5NA) excision cleavage sites. Based on Bryan et al. (1990), van Luenen et al. (1994), Arca et al. (1997), and Zagoraiou et al. (2001).

Consistent with the transposition mechanism proposed for Tc3, Tc1, and Himar1, Osmar5 transposase binds specifically to its TIR through the N-terminal binding domain, as demonstrated previously (Feschotte et al., 2005). An interaction between DBD and TIRs is further supported in this study by the failure of TIR mutations and a DBD deletion to mediate transposition in yeast.

The most significant contribution of this study with regard to the mechanism of transposition of a plant Tc1/mariner element comes from the analysis of the transposon footprints. As mentioned above, transposase endonuclease activity mediates cleavage of the element from the donor site. Like animal Tc1/mariner elements, Osmar5 transposase appears to cut several nucleotides within the element's 5′ end. This view is supported by the composition of footprints generated by Osmar5 excision (Figures 3C and 7). Specifically, the nucleotides located between the remaining TSDs are identical to nucleotides at the element ends. By comparison with the Tc3 footprints and its deduced mechanism, we propose that the Osmar5 transposase cleaves four nucleotides within the element's two 5′ ends, and, at its 3′ ends, precisely at the TSD/element junction. As such, both the excised element and the excision site would contain 3′ overhangs of four nucleotides, thus accounting for the number and composition of nucleotides between the TSDs.

Variation in the 5′ cleavage site has been observed for Tc1/mariner transposases. For example, the transposases from Mos1, Sleeping Beauty, and Frog Prince cleave three nucleotides within the element ends (Dawson and Finnegan, 2003; Miskey et al., 2003; Yant and Kay, 2003). Interestingly, the putative site of Osmar5 cleavage, four nucleotides from the element ends, has also been observed for the Drosophila Minos element (Figure 7), a distantly related member of the Tc1/mariner superfamily (belonging to the DD34E group) (Arca et al., 1997; Zagoraiou et al., 2001).

Although our study provides evidence for the importance of the Osmar5 DD39D motif in the transposition reaction (Figure 6), we were surprised to find that mutation of the second Asp residue (Asp-365) did not completely abolish transposition activity. This could be explained by one of two possibilities: (1) the Asp-365–to–His mutation does not completely disrupt the reaction center, because His may act like a cation and the role of the mutated Asp residue may be compensated by another nearby Asp residue (Asp-375, present in all 34 Osmar elements in the rice genome); (2) the DD39D motif may not accurately reflect the reaction center of the plant elements, as its significance was based on sequence conservation rather than functional criteria. In fact, comparison of the rice transposases and that of Soymar1 revealed five conserved Asp residues (Asp-242, -365, -375, -400, and -405) and two conserved Glu residues (Glu-243 and Glu-261) in the presumed catalytic domain. The fact that mutation of Asp-400, which is not part of the DD39D motif, completely abolished transposition activity supports the view that the exact components of the catalytic motif in plant transposases remain to be defined further.

Although flowering plants are rich in Tc1/mariner elements, it is not known whether they have a preference, like the maize Ac and other hAT elements (Chen et al., 1987; Moreno et al., 1992; Tower et al., 1993), to transpose into linked sites. Local transposition has been demonstrated for other Tc1/mariner elements (e.g., Sleeping Beauty) (Luo et al., 1998; Fischer et al., 2001). In this study, insertion of Osmar5NA was documented to both linked (reporter pOsm5NA) and unlinked (yeast chromosome) sites. Four of the eight excised Osmar5NA elements (independent events) inserted into sites in the reporter plasmid. In addition, this number is probably a considerable underestimate, as only insertions between plasmid genes were recovered in this assay because of a requirement for several plasmid functions. However, although these data strongly suggest a preference for local transposition of Osmar5NA, target selection in the yeast assay may have been influenced by the location of Osmar5NA on a plasmid. This ambiguity can be addressed in future experiments by analyzing transposition from an Osmar5NA reporter construct that is integrated into the yeast chromosome.

The extreme evolutionary distances involved can also complicate conclusions drawn from the analyses of plant transposases in yeast. For example, it is important to understand whether the observed events are attributable to the properties of the transposase or to the yeast host, or both. In this regard, comparison of the footprints generated by two plant transposases (Ac and Osmar5) in yeast is informative. Footprints generated by Ac and Osmar5 are markedly different (Weil and Kunze, 2000; Yu et al., 2004). The Ac transposase, in either a yeast or a plant host, generates footprints with deletions in the TSD and some that extend into flanking sequences. In addition, nucleotides are not retained from the element ends (Baran et al., 1992; Bancroft and Dean, 1993; Rinehart et al., 1997; Weil and Kunze, 2000). By contrast, the majority of footprints generated by Osmar5 (and other Tc1/mariner elements) contain intact TSDs and nucleotides from the element ends. This difference can be explained by the different transposition mechanisms of Ac/Ds and Tc1/mariner elements. The prevailing model for Ac transposition hypothesizes that the transposase cleaves in the TSD and at the element boundary and that the resultant repair of excision sites produces footprints with inverted repeat structures (Peacock et al., 1984; Kunze and Weil, 2002). By contrast, as discussed above, Tc1/mariner elements have been shown to cleave within the element, and the Osmar5 footprints in yeast are consistent with previously described mechanisms, although transposition activity of Osmar5 in the rice genome has yet to be demonstrated. Together, these data indicate that the very different plant transposases require no host-specific factors, and as such, yeast is an excellent system in which to study diverse transposition mechanisms.

Stowaway MITEs and Osmar Elements

In a previous study, computer-assisted analysis of rice genomic sequence led to the identification of >34 Osmar elements and >22,000 Stowaway MITEs (Feschotte et al., 2003). Several lines of evidence had suggested that Tc1/mariner elements were the source of transposase for the nonautonomous Stowaway elements (Feschotte and Mouches, 2000; Turcotte and Bureau, 2002; Feschotte et al., 2003). Specifically, they have related TIRs and the same TA dinucleotide TSD. For this reason, it was surprising that none of the Stowaway elements in the rice genome were derived from the Osmar elements by deletion (Feschotte et al., 2003). Thus, to understand Stowaway amplification in plant genomes, it will be necessary to establish functional connections between Stowaway MITEs and plant Tc1/mariner elements. As such, this study provides two important starting points. First, it demonstrates that at least one Osmar element, Osmar5, is active. Second, demonstration of Osmar transposition in yeast provides a valuable assay system to screen for functional partners between Osmar elements and rice Stowaway elements. Without extensive sequence similarity between presumed autonomous elements (the Osmar elements) and nonautonomous partners (the Stowaway elements), it may be necessary to test many, perhaps dozens, of combinations of Osmar and Stowaway pairs to establish functional connections. The assay system described in this study would be ideal for such large-scale screening, with yeast serving as a living test tube in which the relationships among Osmar and Stowaway elements can be dissected to understand the spread of these important elements throughout plant genomes.

METHODS

Yeast Strain and Plasmid Construction

Excision assays were performed after transformation of the yeast haploid strain DG2523 (MATalpha ura3-167 trp1-hisG leu2-hisG his3-del200 ade2-hisG) (obtained from David Garfinkel). The plasmid containing the Osmar5 transposase, pOsm5Tp, was constructed from plasmid pRS416 (New England Biolabs) as follows. First, the gal1 promoter was inserted between the SacI and NotI sites, and the cyc1 terminator was inserted into the KpnI site (resulting in plasmid pRS416-gal1). Then, the fragment between SacI and NaeI from pRS416-gal1 was cloned into the corresponding sites in plasmid pRS413 (New England Biolabs), resulting in plasmid pRS413-gal1. Finally, the coding sequence of the Osmar5 transposase (previously described by Feschotte et al., 2005) was cloned between the BamHI and EcoRI sites (downstream of the gal1 promoter) of pRS413-gal1, resulting in plasmid pOsm5Tp. The reporter plasmid containing the nonautonomous Osmar5 element, pOsm5NA, was constructed as follows. First, Osmar5NA was constructed using PCR and rice (Oryza sativa) genomic DNA from cv Nipponbare to amplify sequences from the ends of Osmar5 (562 and 319 bp from the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively) and joining the resultant PCR products with a linker sequence (available upon request). The combined fragment of 950 bp (including TA at both ends) was inserted into the XhoI site of pWL89A (Yu et al., 2004), resulting in plasmid pOsm5NA. The orientation of Osmar5NA insertion is opposite that of ade2 transcription (the other orientation results in leaky expression of ADE2).

Yeast Transformation and ADE2 Revertant Selection

Transformation reactions (50 μL of competent cells, 5.8 μL of 5 mg/mL denatured salmon sperm DNA, 1 μL [∼200 ng] each of plasmids pOsm5Tp and pOsm5NA, and 400 μL of 50% PEG-3500 buffer [Gietz and Woods, 2002]) were incubated at 42°C for 45 min. Cells were collected and plated on plates containing complete supplement mixture (CSM) (Q-BIOgene), 2% galactose, and 1% raffinose but lacking histidine and uracil. Colonies appeared after 3 to 4 d of incubation at 30°C and were grown to saturation at room temperature (∼10 d). ADE2 revertants were selected from the double transformants by streaking colonies onto CSM plates containing 2% galactose and 1% raffinose but lacking adenine. To calculate excision frequency, colonies from plates lacking histidine and uracil were picked into 50 μL of water, of which 49 μL was plated onto CSM plates containing 2% galactose but lacking adenine and 1 μL was used for 105 or 106 dilutions. Of the diluted yeast cell suspension, 49 μL was plated on YPD (yeast extract/peptone/dextrose) or CSM plates lacking histidine and uracil to calculate the total number of live yeast cells in the cell suspension. The revertant frequency was calculated as the number of ADE2 revertants per cell.

Footprint Analysis

ADE2 revertant colonies were cultured in YPD liquid medium overnight or in CSM drop-out medium lacking adenine for 2 to 3 d. Plasmid DNA was extracted using the E.Z.N.A. yeast plasmid kit (Bio-Tek). PCR primers used to detect the excision of Osmar5NA on pOsm5NA were 5′-CTGACAAATGACTCTTGTTGCAGGGCTACGAAC-3′ and 5′-TGGAAAAGGAGCCATTAACGTGGTCATTGGAG-3′. PCR products were sequenced directly.

Genomic DNA Gel Blot Analysis

Genomic DNA (100 ng) from ADE2 revertants was extracted using the E.Z.N.A. yeast DNA kit (Bio-Tek), digested with DraI, and resolved on an agarose gel (1%). DNA was blotted onto a Hybond N+ nylon membrane (Amersham Biosciences) using capillary transfer in 20× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl and 0.015 M sodium citrate). Probes were prepared with the DECA prime II kit (Ambion) using Osmar5NA as template. Hybridization and washing conditions were as described by the supplier (ULTRAhyb ultrasensitive hybridization buffer; Ambion).

Plasmid Recovery from ADE2 Revertant Genomic DNA

Genomic DNA (30 to 100 ng) from ADE2 revertants was transformed into Escherichia coli competent cells (Invitrogen), and transformants were selected on Luria-Bertani plates with carbenicillin (50 mg/L). Plasmid DNA was extracted from transformant colonies. Because there were two plasmids in the genomic DNA samples, PCR amplification of the ade2 5′ UTR was used to identify strains containing pOsm5NA-d.

Mutagenesis of Osmar5 Transposase and TIRs

To delete the DBD of Osmar5 transposase, a BamHI site was created using site-directed mutagenesis at the junction of the DBD and the catalytic domain (primer 5′-AGGAAAGGCTGCAGTGGTGGATCCCTATGCTAGATCCGCACACA-3′) so that a BamHI fragment (with the DBD) could be removed and the remaining plasmid could be self-ligated. Site-directed mutagenesis of transposase sites Met-220, Asp-242, Asp-365, Asp-400, and Asp-405 was performed with the QuikChange multi-site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) using primers 5′-GGCTGCAGTGGTGTGTTTCTATACTAGATCCGCACACATTGCCAA-3′, 5′-ATGGAAAATATTATCCACATACATGAGAAATGGTTCAATGCATCA-3′, 5′-AAAACCATATGGATTCAGCAGCATAATGCTAGAACTCATCATCCT-3′, 5′-CCTCCAAATTCCCCGCATATGAATTGTCTAGATCTTGGATTCTTT-3′, and 5′-CCAAATTCCCCGGATATGAATTGTCTACATCTTGGATTCTTTGCT-3′, respectively. Primers for mutagenesis of Osmar5NA TIRs were 5′-AAAAACAAGAAAATCGGACCTCGAGTAGTCGCTGCGATACACAAAACCTGCCGTTTCACC-3′ and 5′-CCATACTTGATCTCGAGTACACCGTCGGTCCCACAAAACATAAAATTTTAAGGTTAGCAG-3′. Mutagenesis reactions of 25 μL contained 100 ng of template vector and 0.5 μL of Quik solution. Site-directed mutagenesis was also performed of the Osmar5 TIRs using pOsm5NA as template. All plasmids were sequenced to confirm the presence of the targeted mutation. ADE2 revertant frequencies were calculated for all mutant constructs.

Inverse PCR

Genomic DNA from ADE2 revertants (∼100 ng) was digested with DraI, purified (with a PCR purification kit [Qiagen]), and ligated with T4 DNA ligase (in 35 μL at 25°C for 3 h, then overnight at 6°C). Ligation products (5 μL) were amplified with primers (5′-CGCACTTCTTTTTTCTGGTTCACCTCCACGTATAC-3′ and 5′-CTGGATGCATGTACAAATGCTGTAAATGACAGC-3′) and either Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene) or Phusion DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) using the same cycling conditions for both enzymes (98°C for 45 s; 35 cycles of 98°C for 45 s, 58°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 2 min; and 72°C for 10 min). PCR products were sequenced directly, and the resultant sequences were used as queries for BLAST searches to determine Osmar5NA insertion sites.

Accession Numbers

The GenBank accession numbers for Osmar5 used in this study are AP008207 and AP003294.

Acknowledgments

We thank David J. Garfinkel and Abram Gabriel for yeast strains, plasmids, and technical assistance. We also thank Ryan Peeler, Cedric Feschotte, Mark Osterland, Tianle Chen, Nathan Hancock, Feng Zhang, and Dawn Holligan for technical assistance and helpful discussions. This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the University of Georgia Research Foundation to S.R.W.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) is: Susan R. Wessler (sue@plantbio.uga.edu).

References

- Arca, B., Zabalou, S., Loukeris, T.G., and Savakis, C. (1997). Mobilization of a Minos transposon in Drosophila melanogaster chromosomes and chromatid repair by heteroduplex formation. Genetics 145 267–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auge-Gouillou, C., Hamelin, M.H., Demattei, M.V., Periquet, G., and Bigot, Y. (2001). The ITR binding domain of the Mariner Mos-1 transposase. Mol. Genet. Genomics 265 58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft, I., and Dean, C. (1993). Transposition pattern of the maize element Ds in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 134 1221–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baran, G., Echt, C., Bureau, T., and Wessler, S. (1992). Molecular analysis of the maize wx-B3 allele indicates that precise excision of the transposable Ac element is rare. Genetics 130 377–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, G., Garza, D., and Hartl, D. (1990). Insertion and excision of the transposable element mariner in Drosophila. Genetics 125 103–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau, T.E., and Wessler, S.R. (1994). Stowaway: A new family of inverted repeat elements associated with the genes of both monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous plants. Plant Cell 6 907–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capy, P., Bazin, C., Higuet, D., and Langin, T. (1998). Dynamics and Evolution of Transposable Elements. (Austin, TX: Springer).

- Chen, J., Greenblatt, I.M., and Dellaporta, S.L. (1987). Transposition of Ac from the P locus of maize into unreplicated chromosomal sites. Genetics 117 109–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, J., Forbes, E., and Anderson, P. (1989). The Tc3 family of transposable genetic elements in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 121 47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daboussi, M.J., Langin, T., and Brygoo, Y. (1992). Fot1, a new family of fungal transposable elements. Mol. Gen. Genet. 232 12–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, A.E., Balciunas, D., Mohn, D., Shaffer, J., Hermanson, S., Sivasubbu, S., Cliff, M.P., Hackett, P.B., and Ekker, S.C. (2003). Efficient gene delivery and gene expression in zebrafish using the Sleeping Beauty transposon. Dev. Biol. 263 191–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, A., and Finnegan, D.J. (2003). Excision of the Drosophila mariner transposon Mos1. Comparison with bacterial transposition and V(D)J recombination. Mol. Cell 11 225–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doak, T.G., Doerder, F.P., Jahn, C.L., and Herrick, G. (1994). A proposed superfamily of transposase genes: Transposon-like elements in ciliated protozoa and a common “D35E” motif. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91 942–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy, A.J., Akagi, K., Largaespada, D.A., Copeland, N.G., and Jenkins, N.A. (2005). Mammalian mutagenesis using a highly mobile somatic Sleeping Beauty transposon system. Nature 436 221–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons, S.W., Yesner, L., Ruan, K.S., and Katzenberg, D. (1983). Evidence for a transposon in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell 32 55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcon, A.A., and Aris, J.P. (2003). Plasmid accumulation reduces life span in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 278 41607–41617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feschotte, C., and Mouches, C. (2000). Evidence that a family of miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs) from the Arabidopsis thaliana genome has arisen from a pogo-like DNA transposon. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17 730–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feschotte, C., Osterlund, M.T., Peeler, R., and Wessler, S.R. (2005). DNA-binding specificity of rice mariner-like transposases and interactions with Stowaway MITEs. Nucleic Acids Res. 33 2153–2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feschotte, C., Swamy, L., and Wessler, S.R. (2003). Genome-wide analysis of mariner-like transposable elements in rice reveals complex relationships with stowaway miniature inverted repeat transposable elements (MITEs). Genetics 163 747–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feschotte, C., and Wessler, S.R. (2002). Mariner-like transposases are widespread and diverse in flowering plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99 280–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, S.E., Wienholds, E., and Plasterk, R.H. (2001). Regulated transposition of a fish transposon in the mouse germ line. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98 6759–6764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz, G., and Savakis, C. (1991). Minos, a new transposable element from Drosophila hydei, is a member of the Tc1-like family of transposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 19 6646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz, R.D., and Woods, R.A. (2002). Transformation of yeast by lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol method. Methods Enzymol. 350 87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivics, Z., Hackett, P.B., Plasterk, R.H., and Izsvak, Z. (1997). Molecular reconstruction of Sleeping Beauty, a Tc1-like transposon from fish, and its transposition in human cells. Cell 91 501–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivics, Z., and Izsvak, Z. (2004). Transposable elements for transgenesis and insertional mutagenesis in vertebrates: A contemporary review of experimental strategies. Methods Mol. Biol. 260 255–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izsvak, Z., Khare, D., Behlke, J., Heinemann, U., Plasterk, R.H., and Ivics, Z. (2002). Involvement of a bifunctional, paired-like DNA-binding domain and a transpositional enhancer in Sleeping Beauty transposition. J. Biol. Chem. 277 34581–34588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, G., Dechyeva, D., Menzel, G., Dombrowski, C., and Schmidt, T. (2004). Molecular characterization of Vulmar1, a complete mariner transposon of sugar beet and diversity of mariner- and En/Spm-like sequences in the genus Beta. Genome 47 1192–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvik, T., and Lark, K.G. (1998). Characterization of Soymar1, a mariner element in soybean. Genetics 149 1569–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze, R., and Weil, C.F. (2002). The hAT and CACTA superfamilies of plant transposons. In Mobile DNA II, N.L. Craig, R. Gragie, M. Gellert, and A.M. Lambowitz, eds (Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology), pp. 565–610.

- Lampe, D.J., Churchill, M.E., and Robertson, H.M. (1996). A purified mariner transposase is sufficient to mediate transposition in vitro. EMBO J. 15 5470–5479. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langin, T., Capy, P., and Daboussi, M.J. (1995). The transposable element impala, a fungal member of the Tc1-mariner superfamily. Mol. Gen. Genet. 246 19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkow, K., Buisine, N., Lampe, D.J., and Chalmers, R. (2004). Early intermediates of mariner transposition: Catalysis without synapsis of the transposon ends suggests a novel architecture of the synaptic complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24 8301–8311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, G., Ivics, Z., Izsvak, Z., and Bradley, A. (1998). Chromosomal transposition of a Tc1/mariner-like element in mouse embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95 10769–10773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miskey, C., Izsvak, Z., Plasterk, R.H., and Ivics, Z. (2003). The Frog Prince: A reconstructed transposon from Rana pipiens with high transpositional activity in vertebrate cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 31 6873–6881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, M.A., Chen, J., Greenblatt, I., and Dellaporta, S.L. (1992). Reconstitutional mutagenesis of the maize P gene by short-range Ac transpositions. Genetics 131 939–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock, W.J., Dennis, E.S., Gerlach, W.L., Sachs, M.M., and Schwartz, D. (1984). Insertion and excision of Ds controlling elements in maize. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 49 347–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plasterk, R.H., Izsvak, Z., and Ivics, Z. (1999). Resident aliens: The Tc1/mariner superfamily of transposable elements. Trends Genet. 15 326–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plasterk, R.H.A., and van Luenen, H.G.A.M. (2002). The Tc1/Mariner family of transposable elements. In Mobile DNA II, N.L. Craig, R. Craigie, M. Geller, and A.M. Lambowitz, eds (Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology), pp. 519–532.

- Radice, A.D., and Emmons, S.W. (1993). Extrachromosomal circular copies of the transposon Tc1. Nucleic Acids Res. 21 2663–2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J.M., Dawson, A., O'Hagan, N., Taylor, P., Finnegan, D.J., and Walkinshaw, M.D. (2006). Mechanism of Mos1 transposition: Insights from structural analysis. EMBO J. 25 1324–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinehart, T.A., Dean, C., and Weil, C.F. (1997). Comparative analysis of non-random DNA repair following Ac transposon excision in maize and Arabidopsis. Plant J. 12 1419–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, H., Soto-Adames, F., Walden, K., Avancini, R., and Lampe, D. (1998). The mariner transposons of animals: Horizontally jumping genes. In Horizontal Gene Transfer, M. Syvanen and C. Kido, eds (London: Chapman & Hall), pp. 268–284.

- Robertson, H.M., and Lampe, D.J. (1995). Recent horizontal transfer of a mariner transposable element among and between Diptera and Neuroptera. Mol. Biol. Evol. 12 850–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, E.J., Akerley, B.J., Novik, V.N., Lampe, D.J., Husson, R.N., and Mekalanos, J.J. (1999). In vivo transposition of mariner-based elements in enteric bacteria and mycobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 1645–1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenke, D., Sasabe, M., Toyoda, K., Inagaki, Y.S., Shiraishi, T., and Ichinose, Y. (2003). Genomic structure of the NtPDR1 gene, harboring the two miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements, NtToya1 and NtStowaway101. Genes Genet. Syst. 78 409–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao, H., and Tu, Z. (2001). Expanding the diversity of the IS630-Tc1-mariner superfamily: Discovery of a unique DD37E transposon and reclassification of the DD37D and DD39D transposons. Genetics 159 1103–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr, T.K., and Largaespada, D.A. (2005). Cancer gene discovery using the Sleeping Beauty transposon. Cell Cycle 4 1744–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarchini, R., Biddle, P., Wineland, R., Tingey, S., and Rafalski, A. (2000). The complete sequence of 340 kb of DNA around the rice Adh1-adh2 region reveals interrupted colinearity with maize chromosome 4. Plant Cell 12 381–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosi, L.R., and Beverley, S.M. (2000). cis and trans factors affecting Mos1 mariner evolution and transposition in vitro, and its potential for functional genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 784–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tower, J., Karpen, G.H., Craig, N., and Spradling, A.C. (1993). Preferential transposition of Drosophila P elements to nearby chromosomal sites. Genetics 133 347–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turcotte, K., and Bureau, T. (2002). Phylogenetic analysis reveals stowaway-like elements may represent a fourth family of the IS630-Tc1-mariner superfamily. Genome 45 82–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turcotte, K., Srinivasan, S., and Bureau, T. (2001). Survey of transposable elements from rice genomic sequences. Plant J. 25 169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Luenen, H.G., Colloms, S.D., and Plasterk, R.H. (1994). The mechanism of transposition of Tc3 in C. elegans. Cell 79 293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Pouderoyen, G., Ketting, R.F., Perrakis, A., Plasterk, R.H., and Sixma, T.K. (1997). Crystal structure of the specific DNA-binding domain of Tc3 transposase of C. elegans in complex with transposon DNA. EMBO J. 16 6044–6054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos, J.C., De Baere, I., and Plasterk, R.H. (1996). Transposase is the only nematode protein required for in vitro transposition of Tc1. Genes Dev. 10 755–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos, J.C., and Plasterk, R.H. (1994). Tc1 transposase of Caenorhabditis elegans is an endonuclease with a bipartite DNA binding domain. EMBO J. 13 6125–6132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H., Hartswood, E., and Finnegan, D.J. (1999). Pogo transposase contains a putative helix-turn-helix DNA binding domain that recognises a 12 bp sequence within the terminal inverted repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 27 455–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, S., van Pouderoyen, G., and Sixma, T.K. (2004). Structural analysis of the bipartite DNA-binding domain of Tc3 transposase bound to transposon DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 4306–4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil, C.F., and Kunze, R. (2000). Transposition of maize Ac/Ds transposable elements in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat. Genet. 26 187–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yant, S.R., and Kay, M.A. (2003). Nonhomologous-end-joining factors regulate DNA repair fidelity during Sleeping Beauty element transposition in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 8505–8518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yant, S.R., Meuse, L., Chiu, W., Ivics, Z., Izsvak, Z., and Kay, M.A. (2000). Somatic integration and long-term transgene expression in normal and haemophilic mice using a DNA transposon system. Nat. Genet. 25 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J., Marshall, K., Yamaguchi, M., Haber, J.E., and Weil, C.F. (2004). Microhomology-dependent end joining and repair of transposon-induced DNA hairpins by host factors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24 1351–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagoraiou, L., Drabek, D., Alexaki, S., Guy, J.A., Klinakis, A.G., Langeveld, A., Skavdis, G., Mamalaki, C., Grosveld, F., and Savakis, C. (2001). In vivo transposition of Minos, a Drosophila mobile element, in mammalian tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98 11474–11478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L., Dawson, A., and Finnegan, D.J. (2001). DNA-binding activity and subunit interaction of the mariner transposase. Nucleic Acids Res. 29 3566–3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]