Abstract

This case study describes Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) with a 30-year-old gay man with symptoms of acute stress disorder (ASD) following a recent homophobic assault. Treatment addressed assault-related posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and depressive symptoms. Also addressed were low self-esteem, helplessness, and high degrees of internalized homophobia. Client symptomatology was tracked using the PTSD Symptom Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory over the course of 12 sessions and for a 3-month posttermination session. Symptoms were significantly reduced by the end of the 12-week therapy and were maintained at 3-month follow-up. This case highlights the utility of this therapy in targeting both ASD symptoms and internalized homophobia relating to experiencing a hate crime–related assault. The authors elaborate on theoretical and applied issues in adapting a structured cognitive-behavioral intervention to the treatment of ASD symptoms associated with experiencing a hate crime.

According to national statistics, violent crime in the United States decreased over the past 10 years, yet rates of hate crimes have increased 3.5% (Federal Bureau of Investigations, 2001). Hate crimes based on sexual orientation (16.3%) comprise the third highest category after hate crimes based on race (53.6%) and religion (18.2%). Fifty-six percent of sexual orientation–based hate crimes reported to police were violent offenses (U.S. Department of Justice, 2001). Yet no studies have been conducted on whether standard treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are efficacious for victims of these types of violent offenses.

Hate crimes have been defined as crimes of bias ranging from verbal assault to homicide intended to harm an individual or group because of perceived minority group membership (Herek, 1989). Current federal hatecrime law defines hate crimes as crimes motivated, in whole or in part, by the offender’s bias (Swigonski, Mama, & Ward, 2001). This bias may be demonstrated in a variety of ways, including the presence of bias-related comments, written statements, or gestures made by the offender indicating bias (Federal Bureau of Investigations, 1999). A common feature among definitions of hate crimes is victim perception of the event as bias-related (Herek, Gillis, & Cogan, 1999; Swigonski et al., 2001).

Studies from within the gay/lesbian/bisexual/trans-gender (GLBT) community suggest that experiences with hate crimes are relatively common (D’Augelli & Grossman, 2001). Recent studies have reported 11% to 16% of gay men and lesbians experienced sexual or physicalassaults because of their sexual orientation (Herek et al., 1999; Rose & Mechanic, 2002). One fourth of gay men and one fifth of lesbian women experienced criminal victimization at least once during adulthood due to their sexual orientation (Herek et al., 1999). GLBT youth are also at high risk for bias-related violence from peers, parents, and other adults (Pilkington & D’Augelli, 1996). D’Augelli and colleagues (2002) surveyed GLBT high school students regarding victimization due to their sexual orientation: more than 59% had experienced verbal threats, 24% were threatened with violence, 11% had been physically attacked, 2% were threatened with weapons, and 5% had been sexual assaulted.

Several studies have found increased symptoms of PTSD, depression, anxiety, and anger in victims of homophobic hate crimes as compared with victims of similar, non-bias-related crimes (Herek et al., 1999; Herek, Gillis, Cogan, & Glunt, 1997; McDevitt, Balboni, Garcia, & Gu, 2001; Rose & Mechanic, 2002). Moreover, psychological distress associated with antigay violence may be longer lasting than that seen in gay and lesbian victims of nonbias crimes (Herek et al., 1999; McDevitt et al., 2001).

One explanation for increased distress in victims of antigay violence is that the assault affects the victim’s beliefs about self and the world (Noelle, 2002). Negative beliefs about self and the world have been associated with increased PTSD severity following traumatic events (Harris & Valentiner, 2002; Newman, Riggs, & Roth, 1997; Owens & Chard, 2001). Compared to victims of nonbias crimes, hate crime victims have been found to have more negative beliefs about the benevolence of people and the world (Herek et al., 1999; Herek et al., 1997). In addition to negative beliefs related to traumatic events, experiencing a hate crime may also increase internalized homophobia (Herek et al., 1997; Noelle, 2002). Internalized homophobia is the process in which GLBT people internalize societal negative views of homosexuality (Gonsiorek, 1993). This term has also been called internalized homonegativity (Roderick, McCammon, Long, & Allred, 1998). Higher levels of internalized homophobia have been associated with increased psychological distress, including depression and anxiety, and increased self-blame (D’Augelli et al., 2001; Herek et al., 1997, Meyer & Dean, 1998).

Given the prevalence of both antigay crime and associated psychological distress, identifying beneficial therapeutic interventions is critical (Rivera, 2002). Therapists who specialize in working with GLBT clients may not have training in psychotherapy with trauma victims (Harrison, 2000) and gay-affirming therapies are not necessarily designed for the treatment of posttrauma symptomatology. There is growing interest in the adaptation of cognitive behavioral therapies to GLBT clients (Gray, 2000; Hart, 2001; Martell, 2001; Purcell, Campos, & Perilla, 1997; Safren & Rogers, 2001). Based on results from case studies, cognitive behavioral therapies that are sensitive to the needs of GLBT clients show a great deal of promise (Safren, Hollander, Hart, & Heimberg, 2001; Safren & Rogers, 2001). However, there are no studies to date on adapting CBT treatments to the needs of GLBT victims of hate crimes.

The experience of criminal victimization, such as a hate crime, can be associated with a variety of psychological sequelae including depression, substance abuse, PTSD, and acute stress disorder (Boudreaux, Kilpatrick, Resnick, Best, & Saunders, 1998; Brewin, Andrews, Rose, & Kirk, 1999; Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995). Within the initial month after experiencing a traumatic event, acute stress disorder (ASD), first introduced in the DSM-IV, is the diagnosis describing initial pathological responses (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Although there is overlap between PTSD and ASD symptoms, ASD emphasizes dissociative responses to the traumatic event (Brewin, Andrews, & Rose, 2003; Harvey & Bryant, 2002). Initial ASD has been found to be predictive of later PTSD in violent crime victims both 3 months and 6 months posttrauma (Birmes et al., 2003; Brewin et al., 1999; Bryant, 2003; Harvey & Bryant, 1999). The ASD diagnosis is intended to allow for earlier identification of victims of traumatic events most at risk for developing later psychopathology, thus allowing for earlier interventions (Bryant, 2003; Bryant & Harvey, 2000; Bryant, Sackville, Dang, Moulds, & Guthrie, 1999).

As ASD is still a new diagnosis, there is only a small body of research into effective treatments. Prolonged exposure combined with cognitive restructuring has been found to be effective in preventing later PTSD, among those diagnosed with ASD, up to 4 years posttreatment (Bryant, Moulds, & Nixon, 2003; Bryant et al., 1999). Although results of these studies support the use of cognitive behavioral interventions for ASD, they are based on relatively few studies (Bryant et al., 2003). Given commonalities between PTSD and ASD symptoms, adapting known efficacious cognitive behavioral treatment for PTSD to ASD is a reasonable alternative.

Cognitive-processing therapy (CPT), first introduced as a treatment for PTSD over a decade ago, combines exposure therapy and cognitive restructuring/skill development (Resick & Schnicke, 1992, 1993; Resick, Nishith, Weaver, Astin, & Feuer, 2002). The therapy initially addresses denial and self-blame, then overgeneralized trauma-related beliefs. Overgeneralized trauma-related beliefs are cognitions modified in response to a traumatic event in an extreme and unrealistic way, such as “The world is a dangerous place.” A recent controlled trial examining the efficacy of CPT in the treatment of rape victims with chronic PTSD found CPT to perform equally well in the treatment of PTSD and comorbid depression as compared to prolonged exposure; both therapies performed significantly better than a wait-list control (Resick et al., 2002). Three-months posttreatment, 83.8% of the CPT group and 70.3% of the prolonged exposure groups no longer met criteria for PTSD. CPT was slightly more effective than prolonged exposure in reducing trauma-related guilt. Therefore, CPT may be a more appropriate treatment option for clients presenting with significant guilt (Resick et al., 2002). CPT has been found to be effective in the treatment of PTSD for rape victims (Resick et al., 2002; Resick & Schnicke, 1992), adult survivors of sexual abuse (Owens, Pike, & Chard, 2001), and male adolescents with comorbid conduct disorder (Ahrens & Rexford, 2002).

The present case study explores CPT as treatment of ASD following a homophobic assault. We examine whether depressive and trauma-related symptomatology decreases in response to CPT. In addition, we also examine whether internalized homophobia, as a trauma-related negative cognition, also remits over the course of treatment.

Method

Informed Consent

Before the client began his first session of treatment informed consent was obtained for therapy. After termination, consent was obtained from the client regarding the use of his test scores and clinical information for teaching and for publication as a case study. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was also obtained. Identifying information—including name, age, and aspects of the assault and personal history—has been changed to protect the client’s confidentiality.

Identifying Information

John was a 30-year-old Caucasian gay male who was living alone at the time of initiating therapy. Three days after a bias-related physical assault and robbery, he was referred to therapy by a gay antiviolence organization to address difficulty with sleep, nightmares, excessive startle reactions, increased irritability, and pervasive feelings of guilt related to the assault. John presented for treatment 1 week postassault to a sliding-fee scale university-affiliated clinic that specializes in empirically supported treatments for trauma-related disorders.

Pertinent Historical Information

John was raised with his parents and siblings (one younger brother and one older brother). According to John, his younger brother physically and emotionally abused him throughout childhood. He described both of his parents as emotionally abusive, as well. He noted that most of the emotional abuse pertained to his sexual orientation and perceptions that he did not fit into a traditional male gender role. John reported having intermittent contact with his mother, who, as John described, had been hospitalized for “psychotic depression” for 10 years. His father died of a heart attack 4 years prior to intake.

During school, John reported experiencing frequent ridicule and physical aggression by peers throughout childhood and adolescence. He coped by becoming increasingly withdrawn. John reported feeling estranged from his peers and struggling with periodic bouts of depression throughout adolescence and early adulthood. According to John, his adult friendships were predominantly with heterosexual women. He reported feeling nervous with gay and heterosexual men. However, John described maintaining two long-term romantic relationships with men, one of which ended 1 month prior to his assault. At the time of intake, he was not in a romantic relationship and was not interested in dating.

John was self-identified as gay at the time of intake. His involvement in the gay community was through attending gay nightclubs and bars. John explained that he first “came out” as a gay male in 1988 to a gay male friend. He reported “being out” to his family, but added that he was not comfortable disclosing his sexual orientation at work. The term “coming out” describes voluntarily disclosing one’s sexual orientation and the term “being out” describes not concealing one’s sexual orientation (Coleman, 1982). According to John, most of his heterosexual friends did not know that he was gay. The state in which John resided was one in which same-sex sexual contact was classified as a criminal act under sodomy statutes, discrimination in employment or housing on the basis of sexual orientation was not prohibited, there were no domestic partner benefits, and same-sex marriage was banned (Conte, 1998; Walzer, 2002).

Prior to seeking treatment for the assault, he had been in supportive counseling on three separate occasions. These therapists were seen for issues relating to his degree of comfort with his sexual orientation and for problems with depression. John explained that he was displeased with the treatment he received from the first and the most recent therapists because he perceived them as being judgmental about his sexual orientation. However, he found the second therapist to be helpful in working through thoughts and feelings related to his sexual orientation.

Traumatic Event

John was robbed and physically assaulted after leaving a gay nightclub. According to John, he went home with the assailant after meeting him in the nightclub. Once he arrived at the assailant’s home, he began to feel uncomfortable and perceived that he was at risk of harm. Shortly thereafter, he was threatened with physical assault and forced to drive with the assailant to an Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) to withdraw money. At that point, John stated that the perpetrator told him that he was “doing this” to John because he was a “filthy faggot” and “deserved it” because John was a “fag.” To ensure compliance, the perpetrator threatened to kill John and stated that were John to report the incident to the police, he would accuse John of trying to rape him. The perpetrator stated that “my brother is a cop and I know that the cops will believe me that it was your fault, because you’re a faggot.” After withdrawing money, John was taken to an abandoned field and physically assaulted. John was able to escape from his assailant. He reported walking several miles until he reached a familiar neighborhood. John stated that he experienced a sense of observing himself walking, as if from the outside. Eventually, he found a police officer and reported the assault, despite being terrified that he would in turn be accused of committing a crime. The police were generally sympathetic. Both John and the police felt, based on the perpetrator’s use of antigay slurs, that the assault was a bias-related crime. However, when John met with the prosecuting attorney he was told that he had “asked for it by going home with the guy” and the case was dropped.

Assessment

The initial clinical assessment was conducted by the first author and consisted of a clinical diagnostic interview, comprehensive psychosocial history, and battery of self-report instruments. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for each self-report measure (published means, standard deviations, and reliabilities). Measures are described below.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, Reliability and Raw Scores for Measures of Symptoms and Maladaptive Schemas

| Assessment Points

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | M | SD | Reliability | (Pre) | S2 | S4 | S6 | S8 | S10 | S12 | (2-week) | (3-month) |

| BDI | 8.00 | 9.30 | 0.65 | 18a,b | 12b | 7 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 0c | 0 | 0c |

| PSS | 21.60 | 16.30 | 0.74 | 27b | 18b | 13b | 10 | 6 | 6 | 2c | 1 | 1c |

| NHAI | 61.50 | 14.20 | 0.65 | 102a,b | — | — | 94a | — | — | 62c | — | 57c |

| PBRS | ||||||||||||

| Safety | 3.47 | 1.48 | 0.80 | 3.63 | 3.38 | — | 4.88 | — | — | 4.25 | — | 5.50c |

| Trust | 4.15 | 1.25 | 0.69 | 3.75 | 4.75 | — | 4.63 | — | — | 5.50 | — | 5.38 |

| Power | 4.42 | 1.13 | 0.77 | 3.25a | 3.63 | — | 4.50 | — | — | 4.88c | — | 4.88c |

| Esteem | 4.62 | 1.22 | 0.72 | 3.75 | 4.00 | — | 4.25 | — | — | 4.50 | — | 5.00 |

| Intimacy | 4.31 | 1.13 | 0.85 | 2.75a | 4.25 | — | 4.25 | — | — | 6.00 c | — | 5.50c |

Note. BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; PSS = PTSD Symptom Scale; NHAI = Nungesser Homosexuality Attitudes Inventory; PBRS = Personal Beliefs and Reactions Scale.

More than one standard deviation above published scale mean.

Surpassing cutoff for clinical significance according to measure criteria.

Ipsative z score significantly different from pretreatment score, as compared to the critical difference score (p <.05).

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Ward, Mendelsohn, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961)

The BDI is a 21-item self-report questionnaire measuring characteristic attitudes and symptoms of depression (Beck, Steer, & Garbin, 1988). It has also been used to assess depression in rape victims (Regehr, Regehr, & Bradford, 1998; Resick & Schnicke, 1992) and in victims of hate crimes (Rose & Mechanic, 2002). Internal consistency for the BDI ranges from .73 to .92 with a mean of .86 (Beck et al., 1988). The test-retest reliability for the BDI in psychiatric patients ranges from 0.46 to 0.86, with 0.65 reported for test-retest reliability over a 1-week period for depression patients (Beck et al., 1988). Scores of less than 10 are indicative of little or no depression; scores between 10 and 18 are considered to reflect “mild to moderate” depression; scores between 19 and 29 are considered to reflect “moderate to severe” depression; and scores over 30 are indicative of “severe” depression.

PTSD Symptom Scale (Foa, Riggs, Dancu, & Rothbaum, 1993)

The PTSD symptom scale is a 17-item self-report measure indicating symptom frequency for 17 PTSD symptoms. The total PTSD score is calculated as the sum of the frequency ratings. A score of less than 10 is considered to reflect “mild” PTSD; scores between 10 and 27 are considered to indicate “moderate” PTSD; scores greater than 28 indicate “severe” PTSD symptomatology. The scale was normed on recent (1-month) female sexual and nonsexual assault victims. One-month test-retest reliability (r = .74) is reasonable, given that the test is not intended to measure trait characteristics (Foa et al., 1993).

Modified Nungesser Homosexuality Attitudes Inventory (Nungesser, 1983)

The Modified Nungesser Homosexuality Attitudes Inventory (NHAI) is a 37-item self-report instrument measuring internalized homonegativity. This scale is considered to be among the most comprehensive and empirically validated of measures available for examining gay male internalized homonegativity (Mayfield, 2001). Participants indicate agreement or disagreement with items on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). Internal consistency, as measured by coefficient alpha, has been reported as ranging from .90 to .95 (Nungesser, 1983; Shidlo, 1994). Higher scores reflect greater levels of internalized homophobia and correlate with higher depression and lower self-esteem (Nicholson & Long, 1990; Shidlo, 1994). The scale was normed on a heterogeneous sample of gay men (Nungesser, 1983). There is no published test-retest reliability on this measure. However, a modified version of this measure was administered to gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents (Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, & Gwadz, 2002). Follow-up analyses of this data found that this modified version of the NHAI had test-retest reliabilities ranging from .65 through .69 over a 6-month time period (M. Rosario, personal communication, November 20, 2003).

Personal Beliefs and Reactions Scale–Revised (PBRS; Mechanic & Resick, 2000; Resick, Schnicke, & Markway, 1991)

The PBRS is a 50-item self-report inventory assessing cognitions affected by traumatic events. This self-report questionnaire consists of statements rated from 0 (not at all true for you) to 6 (completely true for you). The scale used in the present study differs from the original in that the original scale was specific to rape victims and the revised scale is “trauma-neutral.” The PBRS was normed on recent female sexual and non-sexual assault victims. The PBRS yields several subscales reflecting cognitions thought to be most affected by interpersonal trauma, including beliefs about safety, trust, power/control, esteem, and intimacy (McCann & Pearlman, 1990). The PBRS distinguishes between victims with and without PTSD, appears sensitive to treatment effects, and has convergent validity with other measures of trauma-related cognitions (Foa, Ehlers, Clark, Tolin, & Orsillo, 1999; Owens & Chard, 2001; Owens et al., 2001). Scoring of the PBRS results in higher scores indicating more adaptive cognitions.

Procedure

Presenting Complaints

At intake, John’s predominant concerns included feelings of guilt and irritability. He expressed concerns about intrusive memories, nightmares, and distress at reminders of the assault. In the week between the assault and his first session, he reported thinking about the assault and avoided leaving his home. Despite feelings of emotional detachment, John coped with his distress by calling acquaintances repetitively. John was found to meet diagnostic criteria for ASD at the time of his initial intake and to have met criteria for one past major depressive episode. He was evaluated for other disorders, including current major depression and social phobia, but did not meet full diagnostic criteria.

Therapist

Therapy was conducted by the first author, who at the time of treatment was a doctoral student in clinical psychology. The therapist was trained by Dr. Patricia Resick in conducting CPT (Resick & Schnicke, 1993). The therapist had taken two graduate-level courses relevant to mental health issues among gay/lesbian clients. She was also active in working with the GLBT community. The therapist was supervised on a weekly basis by a Ph.D. licensed clinical psychologist with extensive clinical expertise in cognitive behavioral treatments for PTSD (Dr. Pal-lavi Nishith).

Case Conceptualization

John reported a history of negative consequences associated with his sexual orientation ranging from verbal ridicule to assault. This occurred in the context of an absence of positive gay role models, social support regarding his sexual orientation, or positive information about gay identity (Rosario, Hunter, Maguen, Gwadz, & Smith, 2001). This is significant because it has been proposed that gay men experience higher degrees of stress due to the stigmatization of being gay in a society that perceives homosexuality negatively (Cochran, Sullivan, & Mays, 2003; Rosario et al., 2002). This stigmatization leads to the internalization of negative images of gay men (Carragher & Rivers, 2002). Thus, the combination of negative societal messages regarding homosexuality and personal experiences of negative consequences related to his sexual orientation likely led John to develop negative beliefs about himself. This especially affected his sense of self-esteem, his beliefs about intimacy, and perceived ability to exert control over others when needed. Behaviorally, John was likely to be compliant and avoidant of conflict. These coping styles, due to their inflexibility, may have increased his risk for victimization. In addition, John’s beliefs left him vulnerable to psychological distress when he was victimized, because they confirmed previous maladaptive cognitions.

Treatment

John was seen for 1 session of assessment and 12 sessions of CPT. He was then seen for 3 maintenance sessions to monitor his progress. CPT is a cognitive behavioral therapy comprised of both written exposure and cognitive restructuring to help survivors process the emotional content of traumatic events and modify maladaptive beliefs that may have developed in response to traumatic events.

The first session was spent educating John about common reactions to trauma, including ASD and PTSD, and reviewing the treatment rationale. The first homework assignment was the impact statement, where the client was instructed to write about the meaning of his victimization experience and how it affected his views of himself, others, and the world. In this statement, he was also asked to address how the experience affected his beliefs about safety, trust, power, esteem, and intimacy. The goal of this assignment is predominantly to allow the therapist to identify problematic beliefs affected by the traumatic event.

The second session was dedicated to reviewing the impact statement and introducing daily thought records. John expressed an unusual degree of concern about reading his impact statement. His concern seemed to be based on worries that his statement would not be “good enough” and that he would be censured. John endorsed a great deal of self-blame for the attack, expressed concerns about his judgment, and described beliefs about his inability to control future risks. There were several themes in the impact statement relevant to his sexual orientation; John believed that he deserved to be assaulted because he was gay and because he went home with someone from a bar. He also expressed concerns about safety; because he felt that his sexual orientation was the reason he was targeted for the attack, he believed that this placed him at high risk for future assaults. This latter belief was not entirely inaccurate, given rates of victimization in the GLBT community. This issue was addressed in more detail during later stages of treatment.

During the written exposure component of CPT, John was initially fearful that the therapist would think the assault was his fault. The first written account of the assault was disjointed and devoid of affect but was not atypical for an initial written exposure, which are often characterized by incompleteness and a lack of emotional expression (Resick & Schnicke, 1996). John reported feeling scared and sad while writing his account, but did not express much affect during the in-session reading. As is standard in CPT, John and the therapist discussed his account, after which John rewrote his description. His second account was more detailed and organized than the first, and included more of John’s perceptions of events. While reading the second account aloud, John remained composed but, upon reaching the point at which he thought the perpetrator was going to kill him, he became tearful.As he continued to read the account, John experienced an increase in affect when describing the perpetrator stating that he deserved it because he was a “faggot” and that the police would think he deserved it too. John also became tearful describing wandering through the streets alone, feeling cold and too frightened to call a police officer.

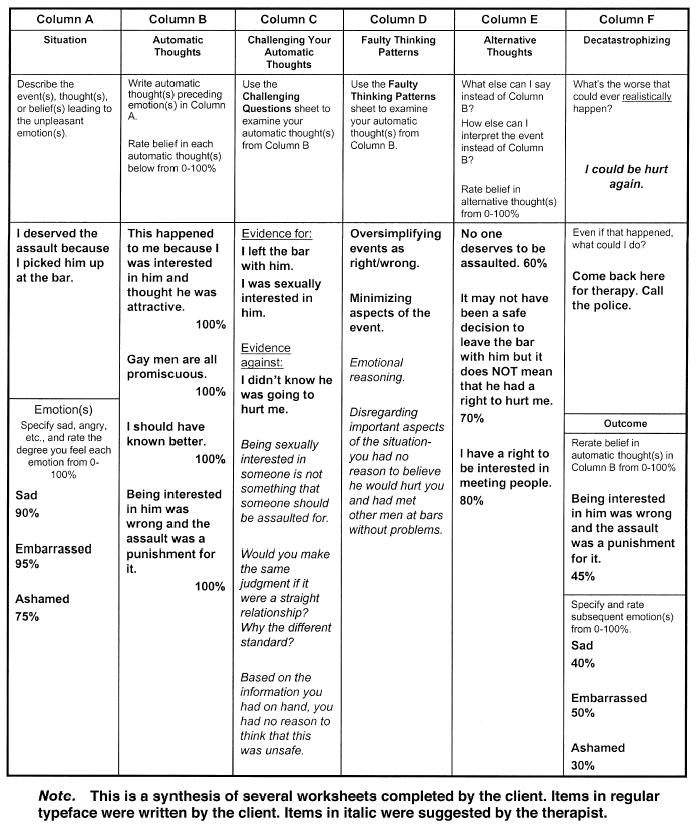

Cognitive restructuring techniques were then utilized to help John address beliefs about the assault and about himself as a gay man. This component of treatment included education regarding connections between thoughts and emotions; cognitive techniques including identifying and challenging faulty cognitions; and modules addressing aspects of the traumatic event pertaining to themes of safety, trust, power, control, and intimacy. John was able to identify several distorted cognitions associated with intense negative affect. Some of these beliefs were specifically assault-related, such as “I should never have gotten out of the truck” and “All strangers are dangerous.” Some beliefs germane to issues around his sexual orientation, such as concerns about future antigay violence and fears of being fired because of his sexual orientation, were not necessarily inaccurate beliefs. As discussed earlier, there are risks of antigay victimization for GLBT individuals and GLBT individuals do experience discrimination (D’Augelli & Grossman, 2001). At the same time, John appeared to be overestimating the probabilities of some of those risks. Therapy consisted of helping John examine evidence supporting and refuting those beliefs and evaluating the intensity of his emotional reactions to determine the degree to which the beliefs were helpful and accurate. Other thoughts were related to preexisting internalized homophobic beliefs exacerbated by the assault, such as “All gay men are promiscuous” and “No one will ever love me because I am gay.” These beliefs were addressed using the same cognitive techniques used to address specific trauma-related faulty cognitions (see Figure 1, Challenging Beliefs Worksheet, for example). As they complete the form, clients are asked to identify faulty cognitions, rate the intensity of their emotional response to the situation, challenge the cognitions, generate alternative beliefs, and re-rate their emotional responses.

Figure 1.

Challenging Beliefs Worksheet.

There were complex interactions between John’s sexual orientation, experiences in childhood, and reaction to the traumatic event. For example, in Session 10, John identified that childhood experiences in which his father would ridicule him for perceived weaknesses had taught him to maintain control over his own emotions at all times. Moreover, ridicule and abuse he experienced at the hands of his younger brother and peers taught him that he was powerless. John also noted that he had coped with the assault through numbing and passivity, skills that had been useful for him in childhood. By identifying these connections, he was then able to decrease his level of self-blame for not resisting during the assault.

Over the course of the cognitive restructuring component of CPT, John became more comfortable with gradations of trust, intimacy, and esteem rather than seeing these concepts in all-or-nothing terms. It also became clear that fears of being disliked and rejected had contributed to his reluctance to act on his instincts during the assault. He reported feeling uneasy about leaving the bar with the perpetrator but did not want to upset the perpetrator by leaving too early. This fear of rejection and resulting fear of setting limits remained a central theme throughout treatment. One example of this was that John was asked by the therapist if he would come in for a session at 5:00 A.M. He immediately assented, without discussing other scheduling alternatives. This was then used as an example in session of his difficulty in refusing even unreasonable requests. As John’s beliefs about consequences of rejection were addressed along with his view of himself as someone worthwhile and worth protecting, John began to set limits with friends, then with coworkers, and lastly with his brothers. These behavioral changes were supported and supplemented by teaching John basic assertiveness skills. The final session involved reviewing John’s progress and having John read a new impact statement. The new impact statement reflected John’s sense of pride and accomplishment; he stated, “No one deserves to experience what happened to me but I know now that I can get through this.”

Results

Visual Inspection of Raw Data

The raw data for the outcome measures at each assessment point are presented in Table 1. At intake, all of John’s scores but one (PBRS-safety) were above reported means for each measure. BDI and PSS scores both fell within the clinically significant range. Inspection of raw scores suggests improvement in PSS, BDI, NHAI, and PBRS power/control and intimacy beliefs from intake to midtreatment. These changes appear most dramatic in NHAI scores, although the NHAI was still markedly elevated at midtreatment. By the last session of CPT, all scores except for the NHAI and PBRS esteem subscale were below published mean scores, indicating fewer maladaptive trauma-related cognitions and lower symptomatology. The decreases in scores for the NHAI and PBRS intimacy subscale seemed especially marked from midtreatment to the last CPT session. All decreases were maintained at the 3-month follow-up session.

Overview of Statistical Analysis

Visual inspection of data is subject to bias. Therefore, statistical means of evaluating changes across time are necessary. One method of analyzing single-case designs (Mueser, Yarnold, & Foy, 1991; Nishith, Hearst, Mueser, & Foa, 1995; Weaver, Nishith, & Resick, 1998; Yarnold, 1988) has been developed, based on classical test theory (Magnusson, 1967). In addition to providing a less biased measure of change, it provides a more objective definition of “significant” than can be employed when visually inspecting results. Furthermore, it corrects for “error” in the client’s score based on the test’s reported reliability, accounts for chance variation, and controls for repeated analyses (Mueser et al., 1991; Yarnold, 1988).

Calculation of statistically significant change is described elsewhere (Mueser et al., 1991; Nishith et al., 1995; Weaver et al., 1998; Yarnold, 1988). In essence, raw scores on the various scales (PSS, BDI, NHAI, PBRS) were converted to ipsative z scores (an intraindividualized z score), based on the published mean and standard deviation of each variable. This places scores on the same metric, thus allowing comparisons across measures. To determine statistical significance of change across sessions, a critical difference score (CD) was calculated for each scale, based on reported test-retest reliability. Less reliable measures will have larger critical difference scores, requiring greater differences to demonstrate significant change. This method accounts for both measurement error and number of comparisons between observations, thereby reducing the Type I error rate. For a two-tailed test at the overall p<.05 (which was employed in the present study), CD =1.96 ([ J(1 − r)]1/2) , where CD is the critical difference score, J is the total number of comparison points, and r is instrument reliability.

Interpretation of Statistical Analyses

To control for the number of comparisons, we only conducted comparisons between John’s scores at intake, posttreatment scores, and scores at the 3-month follow-up session. John’s symptoms were significantly reduced (p < .05) between intake and end of treatment and these improvements were maintained at the 3-month follow-up point. This pattern of results was true for depressivesymptoms, measured by the BDI (posttreatmentz= −1.96,−-monthz = 21.96, BDICD = 1.64) and posttrauma symptomatology, measured by the PSS (posttreatmentz = −1.53,3-monthz = −1.60, PSSCD = 1.41). This was also true for internalized homonegativity (posttreatmentz = −2.82, 3-monthz = −3.17, NHAICD 5 1.64), beliefs about power/ control (posttreatmentz = 1.44, 3-monthz = 1.44, PBRS powerCD = 1.33) and about intimacy (posttreatmentz =2.88, 3-monthz = 2.43, PBRS intimacyCD = 1.07). Improvements in safety beliefs were not statistically significant at posttreatment, but these decreases continued and weresignificant at the 3-month follow-up visit (3-monthz 5 1.26,PBRS intimacyCD = 1.24). John’s scores on PBRS trust and esteem subscales, though reduced at post- and follow-up assessment points, were not statistically significant.

Clinical Functioning at Follow-up

At the 3-month follow-up visit, John no longer met criteria for ASD or PTSD. He denied symptoms of depression and only endorsed one symptom of PTSD (feelings of detachment). John reported a number of life changes. These included a new same-sex dating relationship that, at the 3-month follow-up visit, John had maintained for 2 months. John reported that he had expanded his involvement in the gay community in various ways, including attending the gay pride event and joining a gay-positive church. John stated that he had disclosed his sexual orientation to a number of friends and coworkers and had been pleasantly surprised by their lack of censure.

Postscript

Several informal contacts with John indicated that 1 year after ending treatment he continued to do well. He reported no resurgence of PTSD or depressive symptoms and he reported continued involvement in the gay community.

Discussion

CPT has empirical support for treatment of PTSD related to rape and child sexual abuse in female trauma survivors (Owens et al., 2001; Resick et al., 2002). This case study illustrates its utility as a therapy for a gay male victim of a homophobic assault. CPT successfully treated John’s posttrauma symptomatology, including symptoms of ASD and depression. In addition, cognitive therapy, conducted by a therapist experienced in working with GLBT clients, markedly reduced the client’s degree of discomfort with his sexual orientation. This case provides an important expansion on the utility of CPT across multiple domains, including trauma type, sexual orientation of the client, and trauma acuity.

Treatment of Hate Crimes

Despite the continued increase in rates of hate crimes and associated negative impact on individuals and larger communities, research into treatment implications is notably lacking (Boeckmann & Turpin-Petrosino, 2002; Levin, 1999; Noelle, 2002; U.S. Department of Justice, 2001). This case study focused on treatment for the victim of a homophobic assault, in part because hate crimes based on sexual orientation comprise the third largest group (U.S. Department of Justice, 2001). In addition, there is more research on the impact of antigay crimes than research on the impact of other types of bias crimes, such as those based on race, religion, ethnicity, disability status, or gender (Garofalo, 1997; McPhail, 2002; Oliver, 2001; Perry, 2002). Clearly there is a need to examine whether research based on antigay crimes can be generalized to other types of hate crimes.

John’s reaction to experiencing a bias-related crime was consistent with existing literature. For John, this was not just an assault but an assault upon his identity. This interpretation was intensified by the assailant’s use of homophobic slurs. The meaning of those words for the client was multilayered; it included the direct motivation for the current crime but also included the ridicule and abuse John had experienced in childhood at the hands of his brother and peers and negative images of gay men perpetuated throughout our society (Berrill & Herek, 1990). Therefore, it is not surprising that both exposure and cognitive restructuring components of treatment addressed the moment when the perpetrator told John that he deserved the assault because of being gay.

Another relevant issue in the treatment of hate crimes is that hate crimes are typically targeted toward groups with marginalized status. Thus, victims may be disenfranchised from the legal system. Many victims of antigay violence are too afraid of the police response to report the crime (Bernstein & Kostelac, 2002; Herek, Cogan, & Gillis, 2002; Kuehnle & Sullivan, 2001). The perpetrator, in this case, preyed upon these fears by threatening to accuse John of sexual assault were he to go to the police. It is a testament to John’s courage that he still contacted the police and reported the crime. The reactions of police officers were supportive and encouraging; however, the reaction of the prosecuting attorney (i.e., being told that the event was his fault and having charges dropped) can be seen as an example of the types of secondary victimization that hate crime victims can experience (Berrill & Herek, 1990). This type of negative response highlights the need for community-based changes to reduce the acceptability of stigmatization toward GLBT individuals and thereby reduce the frequency of these types of responses to GLBT victims of hate crimes (Bernstein & Kostelac, 2002). On an individual basis, both types of official responses were addressed in treatment; the positive responses were used as evidence to counter overgeneralized maladaptive beliefs such as “I can’t tell anyone I’m gay.” At the same time, the response from the prosecuting attorney goes to illustrate the point that not all of John’s negative beliefs were maladaptive or inaccurate. It is when these beliefs became overgeneralized to everyone that they became inaccurate, thereby causing John such difficulties as having trouble trusting and feeling unsafe. John worked on acquiring skills during therapy to help him evaluate the accuracy of these beliefs.

Impact of Sexual Orientation

Consistent with other case studies examining cognitive behavioral therapies for gay, lesbian, and bisexual clients, cognitive behavioral therapy was a good treatment paradigm for John (Padesky, 1989; Purcell et al., 1997; Safren et al., 2001; Safren & Rogers, 2001). John’s situation is an excellent illustration of the need for the clinician to balance attending to both John’s presenting symptomatology and to his sexual orientation (Davison, 2001; Safren & Rogers, 2001).

John’s sexual orientation was important to address as part of his cultural context. His historical experiences of abuse and rejection in childhood and adolescence linked to his sexual orientation may have left him more vulnerable to psychological distress in the face of this assault (D’Augelli, 1998; Hershberger & D’Augelli, 1995; Rivers & D’Augelli, 2001). This does highlight the importance of assessing both a victimization history and a full psychosocial history. In John’s case, these early experiences may have formed maladaptive beliefs about himself and about others that were then strengthened by the assault.

John demonstrated high degrees of initial internalized homophobia (score = 102; published mean = 61.50). Again, it is impossible to tell to what extent this preceded the assault. Given John’s level of involvement in the gay community and degree of secrecy around his sexual orientation, it seems likely that he had high degrees of internalized homophobia that were then further elevated by the assault. Despite these initial high scores, John’s internalized homophobic beliefs appeared to respond well to CPT, with the majority of the decrease appearing to occur during the cognitive restructuring portion of the therapy rather than the exposure component. These beliefs were treated in the same way as any other maladaptive cognition. The behavioral changes he made over the course of therapy were perhaps the greatest sign of the reduction of John’s level of internalized homophobia. These included expanding his range of social networks in the gay community, increased openness with friends about his identity, and attendance at a variety of GLBT community events.

One component that may have facilitated John’s treatment gains was having a therapist knowledgeable about the GLBT community. Had John been treated by a therapist who endorsed some of the maladaptive beliefs espoused by John, his outcome may have been less positive (Hart, 2001; Martell, 2000; Safren & Rogers, 2001). Moreover, the treating therapist was aware of some of the legal and social ramifications of being gay in the state where John resided. Ignorance in these matters can lead naïve clinicians to underestimate the degree of risk associated with potential self-disclosure. The therapist was then able to act as an informed sounding board for John to explore his beliefs and fears about coming out to friends and coworkers. The therapist was also able to help the client identify additional resources for social support within the GLBT community in his area.

Trauma Acuity

There are tremendous potential benefits in identifying those at risk for developing chronic PTSD and finding effective early interventions to prevent the development of this disorder (Bryant et al., 1999; Bryant, 2003). The strength of the diagnosis of ASD is that, theoretically, it may allow for earlier and more precise identification of those at risk for PTSD and thereby facilitate earlier interventions. The majority of studies examining ASD as a predictor of PTSD have found that approximately three quarters of those diagnosed with ASD develop PTSD (Birmes et al., 2003; Brewin et al., 1999; Bryant, 2003; Harvey & Bryant, 1999). However, there have been a number of problems noted with the diagnosis of ASD: one half of those with chronic PTSD after the trauma never met criteria for ASD, thus raising questions about those individuals missed by the ASD diagnosis; the emphasis on dissociation in the diagnosis is not supported by research evidence; ASD may pathologize early normative responses to trauma; it is questionable to have two disorders with similar symptoms differentiated only by the duration of the symptomatology (Bryant, 2003; Harvey & Bryant, 2002). Despite this controversy, given that the presence of an ASD diagnosis seems related to the subsequent development of PTSD, it is important to identify treatment options for those diagnosed with ASD.

The results of early examinations into a combined prolonged exposure/cognitive restructuring protocol are extremely promising as a treatment for ASD (Bryant et al., 2003; Bryant et al., 1999). However, these results are based on relatively few studies (Bryant et al., 2003). In addition, given the degree of symptom overlap between PTSD and ASD, it is questionable whether treatments already developed for PTSD might not be just as advantageous. These treatments also have more empirical support for their efficacy.

This case study examined the use of CPT as a possible intervention for ASD and yielded preliminary but promising results. There were significant reductions from pre-to posttreatment in John’s level of PTSD symptoms and depressive symptoms, and these reductions were maintained through the 3-month follow-up period. Clearly, these results would need to be replicated in a larger-scale controlled trial to establish treatment efficacy. However, if these results were replicated, CPT might provide a beneficial alternative treatment.

Limitations

Natural recovery could have played a role in John’s symptom improvement. John was seen within the time period during which victims of traumatic violence tend to see the most spontaneous improvement in symptoms (Gilboa-Schechtman & Foa, 2001; Rothbaum, Foa, Riggs, Murdock, & Walsh, 1992). Furthermore, not every individual diagnosed with ASD develops more chronic psychopathology, although prospective studies have found that 80% of those with ASD are diagnosed with PTSD 6 months posttrauma (Bryant, Harvey, Dang, & Sackville, 1998). However, John appeared to be at higher risk for developing PTSD given his high degree of distress, previous history of victimization, high degree of initial dissociation, and the elevated risk associated with experiencing a bias-related crime (Birmes et al., 2003; Herek et al., 1999; McNally, 2003; Riggs, Rothbaum, & Foa, 1995; Rose & Mechanic, 2002). In addition, there is no data to suggest that internalized homophobia exacerbated by experiencing a bias-related crime would spontaneously remit.

Implications for Cognitive Behavioral Treatments for Victims of Hate Crimes

This case study provides preliminary support for the utility of CPT in the treatment of hate crimes. It has been proposed that hate crimes may be more devastating than comparable crimes because they are attacks against the individual because of their membership in a marginalized group (Berrill & Herek, 1990; Boeckmann & Turpin-Petrosino, 2002; Levin, 1999). This may then reinforce negative societal views about that group, as well as cognitive distortions about self and about the world. CPT may be a good treatment option for victims of hate crimes, because inherent in the treatment is a means of addressing these cognitive distortions. Therefore, exacerbations in internalized societal beliefs can be addressed without deviating from the treatment protocol.

However, as this case study illustrates, assessment with GLBT clients is crucial. Therapists must not rely on assumptions about the role of sexual orientation but must continually assess and reevaluate. As can be seen in John’s treatment, it was the combination of an efficacious and flexible therapy coupled with a treatment provider who was knowledgeable about treatment of GLBT individuals that contributed to his positive treatment outcome.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the client who bravely reached out for help and persevered through treatment and who now graciously allows his story to be shared with others in the hopes that future clinicians and researchers will be better equipped to treat victims of hate crimes. The authors appreciate the assistance of Rebecca Langer, who helped in the preparation of an earlier draft of this manuscript, Deborah Wise and Mary Larimer for their invaluable comments and suggestions, and Pallavi Nishith for providing clinical supervision and assistance with statistical analyses. This research was supported in part by NIAAA Grant T32AA007455-20 (P.I., Mary E. Larimer, Ph.D.) and by NIAAA Grant F32AA014728-01 (P.I., Debra Kaysen). Portions of this manuscript were presented as a poster at the 35th annual meeting of the Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy, Philadelphia (November, 2001).

References

- Ahrens J, Rexford L. Cognitive processing therapy for incarcerated adolescents with PTSD. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2002;6:201–216. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed text revision. Washington, DC: Author; [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelsohn M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein M, Kostelac C. Lavender and blue: Attitudes about homosexuality and behavior toward lesbians and gay men among police officers. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice. 2002;18:302–328. [Google Scholar]

- Berrill KT. Anti-gay violence and victimization in the United States: An overview. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1990;5:274–294. [Google Scholar]

- Berrill KT, Herek GM. Primary and secondary victimization in anti-gay hate crimes: Official response and public policy. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1990;5:401–413. [Google Scholar]

- Birmes P, Brunet A, Carreras D, Ducasse JL, Charlet JP, Lauque D, Sztulman H, Schmitt L. The predictive power of peritraumatic dissociation and acute stress symptoms for post-traumatic stress symptoms: A three-month prospective study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1337–1339. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeckmann RJ, Turpin-Petrosino C. Understanding the harm of hate crime. Journal of Social Issues. 2002;58:207–225. [Google Scholar]

- Boudreaux E, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Best CL, Saunders BE. Criminal victimization, posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid psychopathology among a community sample of women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1998;11:665–678. doi: 10.1023/A:1024437215004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Rose S. Diagnostic overlap between acute stress disorder and PTSD in victims of violent crime. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:783–785. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Rose S, Kirk M. Acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in victims of violent crime. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:360–366. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA. Early predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;53:789–795. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01895-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bzyant RA, Harvey AG. Acute stress disorder: A handbook of theory, assessment, and treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000. pp. 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, Harvey AG, Dang ST, Sackville T. Assessing acute stress disorder: Psychometric properties of a structured clinical interview. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10:215–220. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, Moulds ML, Nixon RV. Cognitive behaviour therapy of acute stress disorder: A four-year follow-up. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2003;41:489–494. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, Sackville T, Dang ST, Moulds M, Guthrie R. Treating acute stress disorder: An evaluation of cognitive behavior therapy and supporting counseling techniques. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:1780–1786. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.11.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carragher DJ, Rivers I. Trying to hide: A cross-national study of growing up for non-identified gay and bisexual male youth. Clinical Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2002;7:457–474. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Sullivan JG, Mays VM. Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental services use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:53–61. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E. Developmental stages of the coming-out process. In: Paul W, Weinrich JD, Gonsiorek JC, Hotvedt ME, editors. Homosexuality: Social, psychological, and biological issues. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.; 1982. pp. 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Conte A. Sexual orientation and legal rights. New York: John Wiley; 1998. pp. 256–262. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR. Developmental implications of victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. In: Herek GM, editor. Stigma and sexual orientation: Understanding prejudice against lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. pp. 187–210. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Grossman A. Disclosure of sexual orientation, victimization, and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:1008–1027. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Hershberger SL, O’ Connell TS. Aspects of mental health among older lesban, gay, and bisexual adults. Aging and Mental Health. 2001;5:149–158. doi: 10.1080/13607860120038366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Pilkington NW, Hershberger SL. Incidence and mental health impact of sexual orientation victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths in high school. School Psychology Quarterly. 2002;17:148–167. [Google Scholar]

- Davison GC. Conceptual and ethical issues in therapy for psychological problems of gay men, lesbians, and bisexuals. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2001;57:695–704. doi: 10.1002/jclp.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigations. [Retrieved April 27, 2005];Hate crime data collection guidelines, 2004. 1999 http://www.fbi.gov/ucr/hatecrime.pdf.

- Federal Bureau of Investigations. [Retrieved April 27, 2005];Crime in the United States 2001, 2002. 2001 http://www.fbi.gov/ucr/01cius.htm.

- Foa EB, Ehlers A, Clark D, Tolin DF, Orsillo SM. The Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory (PTCI): Development and validation. Psychological Assessment. 1999;11:303–314. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Rothbaum BO. Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1993;6:459–473. [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo J. Hate crime victimization in the United States. In: Davis RC, Lurigio AJ, Skogan WG, editors. Victims of crime. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1997. pp. 134–145. [Google Scholar]

- Gilboa-Schechtman E, Foa EB. Patterns of recovery from trauma: The use of intraindividual analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:392–400. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonsiorek J. Mental health issues of gay and lesbian adolescents. In: Garnets L, Kimmel D, editors. Psychological perspectives on lesbian and gay male experiences. New York: Columbia University Press; 1993. pp. 469–485. [Google Scholar]

- Gray J. Cognitive-behavioural therapy. In: Davies D, Neal C, editors. Therapeutic perspectives on working with lesbian, gay and bisexual clients. Buckingham, England: Open University Press; 2000. pp. 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Harris HN, Valentiner DP. World assumptions, sexual assault, depression, and fearful attitudes toward relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2002;17:286–305. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison N. Gay affirmative therapy: A critical analysis of the literature. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling. 2000;28:24–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hart T. Lack of training in behavior therapy and research regarding lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered individuals. the Behavior Therapist. 2001;24:217–218. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AG, Bryant RA. Acute stress disorder across trauma populations. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1999;187:443–446. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199907000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AG, Bryant RA. Acute stress disorder: A synthesis and critique. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:886–902. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Hate crimes against lesbians and gay men: Issues for research and policy. American Psychologist. 1989;44:948–955. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.6.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Cogan JC, Gillis J. Victim experiences in hate crimes based on sexual orientation. Journal of Social Issues. 2002;58:319–339. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Cogan JC, Gillis JR, Glunt EK. Correlates of internalized homophobia in a community sample of lesbians and gay men. Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association. 1997;2:17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Gillis J, Cogan JC. Psychological sequelae of hate-crime victimization among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:945–951. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Gillis J, Cogan JC, Glunt EK. Hate crime victimization among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1997;12:195–215. [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger SL, D’Augelli AR. The impact of victimization on the mental health and suicidality of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehnle K, Sullivan A. Patterns of anti-gay violence: An analysis of incident characteristics and victim reporting. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:928–943. [Google Scholar]

- Levin B. Hate crimes: Worse by definition. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice. 1999;15:6–21. [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson D. Test theory. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Martell CR. Behavior therapy and sexual minorities: Thoughts on progress and future directions. the Behavior Therapist. 2000;22:194–195. [Google Scholar]

- Martell CR. Including sexual orientation issues in research related to cognitive and behavioral therapies. the Behavior Therapist. 2001;24:214–216. [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield W. The development of an internalized homonegativity inventory for gay men. Journal of Homosexuality. 2001;41:53–76. doi: 10.1300/J082v41n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann L, Pearlman LA. Psychological trauma and the adult survivor: Theory, therapy, and transformation. New York: Brunner/ Mazel; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt J, Balboni J, Garcia L, Gu J. Consequences for victims: A comparison of bias- and non-bias-motivated assaults. American Behavioral Scientist. 2001;45:697–713. [Google Scholar]

- McNally RJ. Psychological mechanisms in acute response to trauma. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;53:779–786. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhail BA. Gender-bias hate crimes: A review. Trauma, Violence and Abuse. 2002;3:125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic M, Resick P. The Personal Beliefs and Reactions Scale. University of Missouri: St. Louis; 2000. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer I, Dean L. Internalized homophobia, intimacy, and sexual behavior among gay and bisexual men. In: Herek G, editor. Psychological perspectives on lesbian and gay issues: Vol. 4. Stigma and sexual orientation: Understanding prejudice against lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Oaks, CA Thousand: Sage Publications; 1998. pp. 160–186. [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Yarnold PR, Foy DW. Statistical analysis for single-case designs. Behavior Modification. 1991;15:134–155. doi: 10.1177/01454455910152002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman E, Riggs DS, Roth S. Thematic resolution, PTSD, and complex PTSD: The relationship between meaning and trauma-related diagnoses. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1997;10:197–213. doi: 10.1023/a:1024873911644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson WD, Long BC. Self-esteem, social support, internalized homophobia, and coping strategies of HIV+ gay men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:873–876. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.6.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishith P, Hearst DE, Mueser KT, Foa EB. PTSD and major depression: Methodological and treatment considerations in a single case design. Behavior Therapy. 1995;26:319–335. [Google Scholar]

- Noelle M. The ripple effect on the Matthew Shepard murder: Impact on the assumptive worlds of members of the targeted group. American Behavioral Scientist. 2002;46:27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Nungesser LG. Homosexual acts, actors and identities. New York: Praeger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver W. Cultural racism and structural violence: Implications for African Americans. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2001;4:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Owens GP, Chard KM. Cognitive distortions among women reporting childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:178–191. [Google Scholar]

- Owens GP, Pike JL, Chard KM. Treatment effects of cognitive processing therapy on cognitive distortions of female child sexual abuse survivors. Behavior Therapy. 2001;32:413–424. [Google Scholar]

- Padesky C. Attaining and maintaining positive lesbian self-identity: A cognitive therapy approach. Women and Therapy. 1989;8:145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Perry B. Defending the color line: Racially and ethnically motivated hate crimes. American Behavioral Scientist. 2002;46:72 –92. [Google Scholar]

- Pilkington NW, D’Augelli AR. Victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth in community settings. Journal of Community Psychology. 1996;23:34–56. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell DW, Campos PE, Perilla JL. Therapy with lesbians and gay men: A cognitive behavioral perspective. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 1997;3:391–415. [Google Scholar]

- Regehr C, Regehr G, Bradford J. A model for predicting depression in victims of rape. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 1998;26:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Nishith P, Weaver TL, Astin MC, Feuer CA. A comparison of cognitive-processing therapy with prolonged exposure and a waiting condition for the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in female rape victims. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:867–879. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Schnicke MK. Cognitive processing therapy for sexual assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:748–756. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Schnicke MK. Cognitive processing therapy for rape victims: A treatment manual. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Schnicke MK, Markway BG. The relation between cognitive schemata and PTSD. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy; New York. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Riggs DS, Rothbaum BO, Foa EB. A prospective examination of symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in victims of nonsexual assault. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1995;10:201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera M. Informed and supportive treatment for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgendered trauma survivors. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation. 2002;3:33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Rivers I, D’Augelli AR. The victimization of lesbians, gay, and bisexual youths. In: D’Augelli AR, Anthony R, Patterson CJ, editors. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual identities and youth: Psychological perspectives. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 199–223. [Google Scholar]

- Roderick R, McCammon SL, Long TE, Allred LJ. Behavioral aspects of homonegativity. Journal of Homosexuality. 1998;36:79–88. doi: 10.1300/J082v36n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Hunter J, Maguen S, Gwadz M, Smith R. The coming-out process and its adaptational and health-related associations among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: Stipulation and exploration of a model. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:113–160. doi: 10.1023/A:1005205630978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J, Gwadz M. Gay-related stress and emotional distress among gay, lesbian and bisexual youths: A longitudinal examination. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:967–975. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose SM, Mechanic MB. Psychological distress, crime features, and help-seeking behaviors related to homophobic bias incidents. American Behavioral Scientist. 2002;46:14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum BO, Foa EB, Riggs DS, Murdock T, Walsh W. A prospective examination of posttraumatic stress disorder in rape victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1992;5:455–475. [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Hollander G, Hart TA, Heimberg RG. Cognitive-behavioral therapy with lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2001;8:215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Rogers T. Cognitive-behavioral therapy with gay, lesbian, and bisexual clients. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2001;57:629–643. doi: 10.1002/jclp.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shidlo A. Internalized homophobia: Conceptual and empirical issues in measurement. In: Greene B, Herek GM, editors. Lesbian and gay psychology: Theory, research, and clinical applications. Vol. 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 176–205. [Google Scholar]

- Swigonski ME, Mama RS, Ward K. Introduction. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services. 2001;13:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Justice. Hate Crimes Reported in NIBRS, 1997–99. [Retrieved April 27, 2005];Office of Justice Programs. 2001 http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/hcrn99.pdf.

- Walzer L. Gay rights on trial: A reference handbook. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO; 2002. pp. 351–352. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver TL, Nishith P, Resick PA. Prolonged exposure therapy and irritable bowel syndrome: A case study examining te impact of a trauma-focused treatment on a physical condition. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 1998;5:103–122. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(98)80023-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarnold PR. Classical test theory methods for repeated measures N = 1 research designs. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1988;48:913–919. [Google Scholar]