Abstract

In this paper we present the foundation of a unified, object-oriented, three-dimensional biomodelling environment, which allows us to integrate multiple submodels at scales from subcellular to those of tissues and organs. Our current implementation combines a modified discrete model from statistical mechanics, the Cellular Potts Model, with a continuum reaction–diffusion model and a state automaton with well-defined conditions for cell differentiation transitions to model genetic regulation. This environment allows us to rapidly and compactly create computational models of a class of complex-developmental phenomena. To illustrate model development, we simulate a simplified version of the formation of the skeletal pattern in a growing embryonic vertebrate limb.

Keywords: computational biology, systems biology, morphogenesis, organogenesis, cell dynamics, Cellular Potts Model

1. Introduction

New information about the many specific biological mechanisms acting at various scales in multicellular organisms is inspiring increasing collaboration between experimentalists and modellers to build predictive simulations of complex biological phenomena. Such simulations must describe interactions among components at the various natural biological scales (molecular, subcellular, cellular and supracellular). While individual organisms and organs have very different structures and behaviours, many of the underlying interactions and components are the same. Thus we can greatly reduce the burden of simulation by building a software framework that includes the fundamental mechanisms and objects important to development, and allows us to specify them and their interactions in a compact way.

In this paper, we adopt this approach to provide a three-dimensional environment for modelling morphogenesis and pattern formation, the generation of three-dimensional structures and arrangements of cells in an organism or its organs, during embryonic development. A version of the code is available as the CompuCell3D1 project on the Web. Morphogenesis involves differentiation, growth, death and migration of cells, as well as changes in the shapes of cells and tissues and the secretion and absorption of extracellular materials.

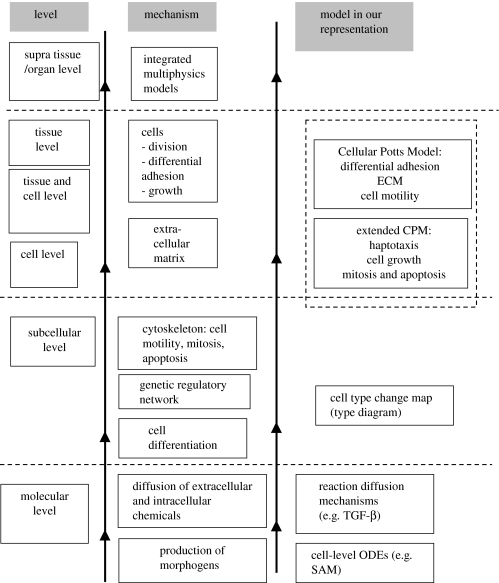

Figure 1 shows the hierarchy of scales our computational environment includes (see table 1 for the corresponding spatial and temporal scales). Information usually flows from finer to coarser scales, but can flow between any pair of submodels. For example, cells can secrete peptide signalling factors under certain conditions, and such factors may act as morphogens, which modify the type of the secreting cell or its neighbours. In this case, a supracellular diffusant affects a subcellular differentiation state. Section 2 justifies our modelling approach and §3 provides biological descriptions of phenomena occurring at different scales and their interactions. We then provide details on each of the blocks in figure 1: §4.1 describes the cell-scale submodel, the Cellular Potts Model (CPM), which is the core module of the computational environment. Sections 4.2 and 4.3 describe molecular-scale submodels, §4.4 a phenomenological, subcellular submodel of the gene regulatory network, and §§4.5 and 4.6 the complete organ-scale model. Our implementation of a computational environment for morphogenesis allows us to construct computer models within the environment, enabling us to study the parameter-rich complexity of the complete biological models that result from webs of interactions between the components of the hybrid model. The software implementation of models requires specification of (i) the submodel components, (ii) the interfaces between interacting submodels and (iii) a simulation protocol that specifies the spatial and temporal order in which the component submodels execute.

Figure 1.

Hierarchy of scales from molecule to organ, and the corresponding mechanisms and modelling approaches. Models/subsystems at coarser scales use information from finer scales. See table 1 for length and time-scales.

Table 1.

Summary of multiscale models.

| submodel | mechanism | modelling approach | length scale | time scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | dynamics of morphogen fields | activator, TGF-β and inhibitor interacting via reaction–diffusion PDEs | μm×10 to mm×10−1 | s×10 to min |

| 2 | establishment of fibronectin field | a grid to accumulate fibronectin secreted by cells, modelled using the Cellular Potts Model | μm | min |

| 3 | upregulation of cell–cell adhesivity | individual cell's gene network modelled using ordinary differential equations | μm×10 | min |

| 4 | dynamics of cells and their response to morphogen fields | Cellular Potts Model | μm | min |

| 5 | mitosis | an ad hoc approach based on a ‘breadth-first’ search incorporated into CompuCell | μm | min |

| 6 | geometry of the limb space | simplified into a three-dimensional rectangular domain | mm to cm | h |

| 7 | definition of subzones in the spatial domain in which mechanisms 1–5 are active | division of discretized space into zones | mm×10−1 to mm | h |

| 8 | terminal differentiation once the desired patterns have formed | based on visualization and observation: consistent with standard biochemical mechanisms | μm×10 | min |

| 9 | domain growth | ad hoc, to allow enough condensation time | μm×100 to mm | h–d |

What justifies a multiscale modelling approach, and why is the cell the natural level of detail to begin with? Macroscopic models, such as Physiome2, which treat tissues as continuous substances with bulk mechanical properties, reproduce many biological phenomena but fail when biological structure develops and functions at the cell scale. Often, direct, cell-level model implementations reproduce phenomena which we see in experiments, but which the continuum model misses. Continuum models to describe materials such as bone, extracellular matrix (ECM), fluids and diffusing chemicals are, however, much less computationally costly than cell-level, development models. Molecular and subcellular models such as V-cell3 or BioSym4 provide detail on aspects of subcellular processes, but often cannot describe even one complete cell, let alone many cells acting in concert. Even a hypothetical ‘perfect’ single cell model (which is probably computationally unfeasible) would not provide an understanding of how cells function in intact organisms. Instead, stoichiometric and reaction kinetics (RK) approaches can efficiently and realistically model cell differentiation and metabolism. A cell-level model such as the CPM can simulate 105–106 cells on a single processor, making organism-scale simulations practical on parallel computers. When appropriate, cell-level models can supply parameters to, and interface with, continuum models, accept parameters from microscopic models, or use phenomenological models of subcellular properties. In this respect, biological modelling is easier than materials modelling, which lacks the natural mesoscopic level of the cell to interpolate between molecule and continuum.

As an example of such model descriptions, we use the general biological concept that interactions of cells via gene products (i.e. molecules synthesized by gene transcription and translation, and their derivatives) generate biologically significant patterns that we can describe mathematically and implement computationally (Newman & Frisch 1979; Meinhardt 1982; Graner & Glazier 1992; Glazier & Graner 1993; Jiang et al. 1998; Zeng et al. 2003; Hentschel et al. 2004; Kiskowski et al. 2004). Gene products may reside inside a cell, on the cell surface, or cells may secrete them. Secreted gene products may remain at their secretion location or diffuse or advect, possibly over long distances. In this paper, we neglect the advection of gene products and consider only their diffusion (see §3 for a justification); we do include motion of cells and their surrounding medium.

As an example of implementing a specific, though simplified, developmental simulation within our computational environment, we construct a model of the dramatic patterning of developing cartilage (i.e. spatio-temporal chondrogenesis) which occurs in the predifferentiated mass of mesenchymal cells during the embryonic growth of the early-stage avian limb bud (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Skeletal pattern formation—time-series of chick limb-bud development in longitudinal section. For each figure, proximal is to the left, distal to the right, anterior up and posterior down. Black represents differentiated cartilage and stipple precartilage condensation. The single bone on the left of each figure is the humerus, the two bones in the mid-limb are the radius and ulna, and the three bones that form at the distal end, beginning on day 6, are the digits (based on Newman & Frisch 1979).

The developing vertebrate limb progressively generates a sequence of increasing numbers of cartilage elements from the body-wall outwards (proximo-distally; see figure 2). In a forelimb, this sequence is (i) humerus, (ii) radius and ulna, (iii) carpals and metacarpals and (iv) digits. The hindlimb displays a similar pattern: (i) femur, (ii) tibia and fibula, (iii) tarsals and metatarsals and (iv) digits. Independent of limb type, element (i) is the stylopod, element set (ii) the zeugopod, and element sets (iii) and (iv), the autopod.

The developing limb presents a number of distinct problems in growth and patterning. How does the gene expression programme interact with generic, dynamic, physical and chemical mechanisms to form an organ? What is the relative contribution of local and long-range signalling? What are specific factors that result in abnormal growth? To succeed, our model must reproduce both normal and abnormal development, and should suggest mechanisms for observed pathologies.

To answer these questions, we need to develop a predictive model. Distinguishing between experimental biological, mathematical and computational models clarifies model building. Limbs display a great variety of structures and functions of varying degrees of organizational complexity. For example, the adaptations of limbs can range from the flippers of a dolphin to the wings of a bird, the hoofed feet of horses, and the dexterous forelimbs of humans. We need to organize our biological study in a manner that clarifies the underlying unity of structure, function and organizational principles, while allowing elaborations to explain specific differences. Continuing with our example, the chicken limb is a widely-studied experimental model (both in vivo and in vitro) of vertebrate morphogenesis and pattern formation. The first step in our simulation strategy is to abstract from the observed experimental behaviours a computationally tractable biological model. Diagrams of biochemical pathways or cell migration are examples of such biological models. We then construct a mathematical model to quantitatively express the phenomena the biological model describes. The mathematical model consists either of sets of differential equations or algorithms, or a combination of the two. We need idealizations to simplify the observed phenomena at this step, but the mathematical model must be rich enough to capture the range of phenomena we wish to predict.

Even idealizations of the simplest organisms are generally too complex to permit us to solve the mathematical models analytically; hence we translate the mathematical model into a computer model or simulation. The commonality of biological processes allows us to build a modelling framework, which permits simple, compact and efficient implementation of mathematical models as computational models. We use the modelling framework to build a composite model of the complex web of interactions of the mathematical model, using submodels representing different scales. To be extensible and reusable (i.e. able to accommodate model elaborations and changes without requiring rewriting of basic code) the computational environment must be modular (i.e. constructed from well-defined, independent components), with well-defined interfaces through which the various submodels interact, allowing us to construct new objects and submodels. Flexibility is essential because of the current rapid growth in our knowledge of cellular and subcellular mechanisms. Neuron5 and Physiome6 are examples of such frameworks.

Multiscale, experimentally motivated simulations have successfully used the CPM to reproduce morphological phenomena in the cellular slime mould Dictyostelium discoideum (Marée & Hogeweg 2001, 2002), vascular development (Merks et al. 2004), vertebrate neurulation (Kerszberg & Changeux 1998) and convergent extension (Zajac et al. 2000, 2003; Zajac 2002). Chaturvedi et al. (2003), and Later Izaguirre et al. (2004), described a simplified, two-dimensional environment, CompuCell7, which integrated discrete and continuum models of biological mechanisms. A highly simplified, sample simulation in this environment reproduced the proximo-distal increase in the number of skeletal elements in the developing avian limb. This paper emphasizes the modelling issues involved in extending the software framework to three dimensions, and implements an experimentally motivated sample simulation of a model of limb development that corresponds more closely to the biological reality (Hentschel et al. 2004). Using this model, we simulate two pathological cases of limb development in addition to normal development.

2. Modelling organogenesis

Organogenesis is the development of organs in living organisms, including their morphogenesis and pattern formation. Our software framework for organogenesis includes three major submodels: the discrete stochastic CPM for cell dynamics, continuum reaction–diffusion (RD) partial differential equations (PDEs) for morphogen production and diffusion, and a type-change map for genetic regulation.

Why do we need cell-level models for organogenesis? Traditionally, models dealing with organogenesis, e.g. the two-dimensional continuum model of chicken limb development in Hentschel et al. (2004), treat both cells and morphogens as continuous fields. Continuum models work well for diffusing chemicals, whose distribution varies over distances much larger than a cell diameter. Modelling the motion of individual morphogen molecules would require a tremendous amount of computer time. By treating their concentrations as continua, we take advantage of computationally efficient, optimal, standard numerical schemes for RD PDEs for secreted morphogens. Models at the cell scale require representation of individual cells, which change shape and association with other cells (see Graner & Glazier 1992, Glazier & Graner 1993) and ECM (see Newman & Frisch 1979; Zeng et al. 2003) when forming different kinds of tissues (epithelia, cartilage, etc.; Hentschel et al. 2004). Cells also move considerable distances during organogenesis, so treating them as a continuum field would require numerical solutions of advection PDEs, which are computationally costly and numerically unstable.

Organogenesis is essentially three-dimensional; it depends on three-dimensional cell rearrangement into well-organized structures. Although two-dimensional simulations provide helpful qualitative insights using limited computer resources (Chaturvedi et al. 2003; Izaguirre et al. 2004), understanding symmetries and symmetry breaking during organogenesis requires three-dimensional modelling and simulation; three-dimensional mathematical and physical models differ qualitatively from those in two dimensions.

For example, in the CPM component of our chick-limb model, a third dimension allows cells to move around barriers, relaxing two-dimensional constraints on producing specific cell-condensation-dependent tissue structures (e.g. the nodular and bar-like precartilage primordia involved in skeletogenesis). In the RD part of the chick-limb model, morphogens and other secreted components serve as both inductive signals (i.e. altering cell type) and haptotactic signals (i.e. inducing preferential cell movement up a gradient of an insoluble ECM molecule; see below). A requirement specific to the three-dimensional RD submodel is that the morphogen patterns must display simultaneous spot-like and stripe-like behaviour (§4.2.2; Murray 1993). In this paper we use a biologically motivated RD model which Hentschel et al. (2004) proposed and solved in two dimensions, but which lacked simultaneous spot and stripe behaviour. These RD equations in three dimensions require additional stabilizing cubic terms, making them structurally more complex than the two-dimensional equations (for details, see §4.2).

3. Biological background: multiple scales in limb organogenesis

Cell condensation is a critical stage in chondrogenesis (Hall & Miyake 2000) (figure 2 shows the stages of chondrogenesis in the chicken limb). Why and how do the initially dispersed mesenchymal cells cluster at specific locations within the paddle-shaped tissue mesoblast that emerges from the body wall, and how do they form the precartilage template for the limb skeleton? While genes specify the proteins (both intracellular and secreted into extracellular space) necessary for morphogenesis, the genes do not, by themselves, specify the distribution of these proteins or their physical effects. Generic physical mechanisms complement and enable the genetic mechanisms (Newman & Comper 1990). Generic mechanisms (in the context of tissue mechanics) are physical mechanisms common to both living and non-living viscoelastic or excitable materials, which translate gene expression into mechanical behaviour (Newman & Comper 1990) and also dynamic chemical processes that regulate the state of chemical reactors, including cells (Newman & Forgacs 2005). The regulation of gene expression is one important aspect of development, but a full description of development requires incorporation of the thermodynamics and mechanics of condensed matter, as well as the pattern-forming instabilities of excitable media at the scales of tissues, organs and organisms.

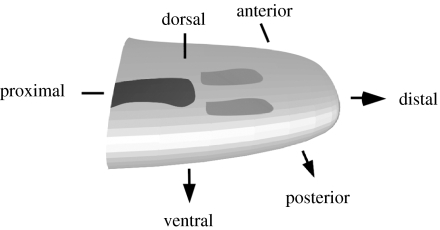

Figure 3 is a schematic of the major axes and the progress of chondrogenesis of a developing vertebrate forelimb. The humerus has already differentiated (black); the radius and ulna are forming (medium grey). The wrist bones and digits are still to form.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of chick-limb organogenesis at mid-development (corresponding to day 5 in figure 2), showing primary axes. The earliest-developing region of the skeleton has differentiated into cartilage (black) by this stage. The region in which the skeletal pattern is forming is undergoing mesenchymal condensation (medium grey). The digits at the distal tip have not yet begun to form.

Limbs in chickens and other vertebrates arise from a mesoblast, consisting of two main populations of predifferentiated mesenchymal cells, precartilage and premuscle cells (reviewed in Newman 1988) covered by a skin, or ectoderm. To start with, precartilage cells pack loosely in the mesoblast. Subsequently, they divide and change position under various influences, finally condensing into patterns that prefigure the bones. As the limb bud elongates, subpopulations of precartilage cells successively condense and differentiate into chondrocytes, beginning in the proximal (nearer to body) region and eventually extending to the distal (far from body) region of the growing limb bud. The distal-most region (the apical zone) progressively shortens in the proximo-distal direction and remains in the predifferentiated mesenchymal state until skeletal development is complete. The ectoderm, a thin sheet of cells tightly attached to one another laterally, ensheathes the mesoblast. The narrow protrusion of the ectoderm that runs in an antero-posterior direction along the distal tip of the limb bud is the apical ectodermal ridge (AER). An apically localized source of fibroblast growth factors (FGFs; see below), which the AER provides under normal circumstances, is necessary for proximo-distal development of the skeleton. The initial precartilage mesenchymal cell type differentiates into other cell types under the influence of various signals. At sites of condensation, cells differentiate into cartilage; at other sites they differentiate into connective tissue (tendon, muscle-associated supporting tissue and, in certain species, interdigital webs) or undergo apoptosis (programmed cell death). The muscle cells of the limb differentiate from a separate population of limb mesenchymal cells (Newman 1988).

Key mechanisms in chondrogenesis include cell motility, and adhesion between different types of cells and between cells and the ECM (Hall & Miyake 2000). Some ECM components are non-diffusing secreted proteins and other polymeric molecules which act as scaffolds or attachment substrata (e.g. fibronectin). The mesenchymal cells distribute uniformly throughout the ECM, which also provides a medium through which morphogens diffuse.

Secreted components have various dynamics and effects. Experiments on the initiation and arrangement of individual skeletal elements in the chicken and the mouse suggest that the secreted morphogens TGF-β, FGF-2 and FGF-8 are key molecules (see Hentschel et al. 2004 for a review). Experiments (Frenz et al. 1989; Downie & Newman 1995; Gehris et al. 1997) show the importance of fibronectin in chondrogenesis. Simulations (Zeng et al. 2003, 2004; Kiskowski et al. 2004; Zeng 2005) of disk-shaped, high-density (micromass) cultures of limb precartilage mesenchyme, suggest that chondrogenic patterns result from haptotaxis (cell movement up or down gradients either of bound chemicals or mechanical properties of the substratum) of cells in response to fibronectin gradients. Fibronectin is a large molecule, which does not diffuse like TGF-β (Lander et al. 2002), although it can spread from its point of production by other mechanisms (Wierzbicka-Patynowski & Schwarzbauer 2003). In our model, we consider two main secreted components—TGF-β, which diffuses through the mesoblast (inclusive of cells and ECM), and fibronectin, which accumulates at sites of secretion. The ground substance of the mesoblast is a dilute aqueous gel containing the glycosaminoglycan (tissue polysaccharide) hyaluronan. We assume that this gel supports the cells and provides a medium for diffusion of TGF-β, and a hypothesized inibitor of chondrogenesis (see below), and for accumulation of fibronectin. This gel, and the cells it supports, both move as the limb grows. We assume that this motion is very slow compared with the morphogens' diffusion speed. This assumption allows us to neglect advection of morphogens by the ECM.

We assume that TGF-β triggers the precartilage mesenchymal cells' differentiation into cells capable of producing fibronectin (Leonard et al. 1991). Cells respond to fibronectin by undergoing haptotaxis up gradients of this ECM protein. In addition, TGF-β upregulates production of the cell–surface molecule N-cadherin, which regulates cell–cell adhesivity (Oberlender & Tuan 1994; Tsonis et al. 1994)

TGF-β can diffuse through the mesoblast. Similar to its action in other mesenchymal tissues (Van Obberghen-Schilling et al. 1988), it is positively autoregulatory in the limb (Miura & Shiota 2000a). Together with a lateral inhibitor of its action or its downstream effectors (Moftah et al. 2002), it can potentially form patterns via RD (Miura & Shiota 2000a,b; Miura et al. 2000; Moftah et al. 2002). Since TGF-β also induces cells to produce fibronectin and upregulates cell–cell adhesivity (Tsonis et al. 1994), it recruits neighbouring cells into chondrogenic condensations (Frenz et al. 1989a,b). Cells in the embryo of the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster respond to DPP, a secreted TGF-β-like morphogen, according to distinct concentration thresholds (Nellen et al. 1996). We have assumed a similar threshold response of mesenchymal cells to TGF-β.

We can consider the developing limb as containing three zones—the apical zone where only cell division takes place, an active zone, where cells rearrange locally into precartilage condensations, and a frozen zone, in which condensations have differentiated into cartilage and no additional patterning takes place. Cell division continues in both active and frozen zones (Lewis 1975). Biologically, distance from the AER, which the concentrations of a subset of the FGFs may signal, may define the zones (Hentschel et al. 2004); however, for simplicity, we assume the zones a priori.

To summarize, the biological framework of the model we develop in this paper considers the following sequence of events during limb formation. (i) The limb bud initially consists of predifferentiated mesenchymal cells in the ECM gel, packing loosely in the mesoblast, which can translocate, divide and produce various morphogens and ECM molecules. (ii) The limb bud has apical, active and frozen zones at different distances from the limb tip, which vary in cellular activity. Cells in the active zone are of a type distinct from those in the apical zone: the former, for instance, can respond to morphogens. (iii) The cells produce TGF-β and its inhibitor, which diffuse through the mesoblast. (iv) If TGF-β (i.e. activator) concentration at a cell location in the active zone is above the response threshold for the cell, the original cell differentiates into another type that can produce fibronectin. Cells exposed to TGF-β also upregulate their adhesivity. (v) Cells surrounded by fibronectin experience an energy barrier to leaving this microenvironment. Cells that have not experienced local threshold levels of activator can respond to, but not produce, fibronectin. (vi) All cell types divide. Consequently, the limb domain grows, with corresponding changes in the boundaries of the three zones.

4. Physical and mathematical submodels and their integration

We describe below specific physical and mathematical representations of key biological mechanisms operating at the various scales of our model. Table 1 summarizes the mechanisms and the corresponding submodels, and their characteristic spatial and temporal scales. For each mechanism, a specific parameter controls the behaviour of the corresponding submodel. Table 2 lists important mechanisms and their control parameters.

Table 2.

Specific roles of important parameters.

| phenomenon | governing parameter | equation |

|---|---|---|

| cell clustering | first term in equation (4.2), detailed in equation (4.3) (CPM) | |

| limb prepatterning and patterning | can equivalently use either of the following: Dx/Dy , γ | RD equations (4.15) and (4.16) |

| haptotaxis | μ(σ) | equation (4.5) |

| cell volume | λσ and vtarget | equation (4.5) |

| cell growth leading to mitosis | vtarget as a function of time | equation (4.5) |

| membrane fluctuations | T | equation (4.1) Boltzmann dynamics in the CPM |

4.1 Modelling cellular and tissue scales: the CPM framework

Cell-scale processes are the basis for the complexity of highly-evolved multicellular organisms, as well as colonies of unicellular ones. In multicellular organisms, ECM plays an important role (§3). We can model ECM components either at the scale of cells or smaller scales. In this paper, we choose to model the ECM gel at the cell scale, and fibronectin at a finer scale.

4.1.1 Physics of cell sorting

Condensation requires sorting of similar types of cells into cell clusters. Steinberg disaggregated cells, re-mixed them randomly, and found that they sorted into coherent clusters of similar cell types (Steinberg 1963, 1998). He proposed the differential adhesion hypothesis (DAH), which states that cells adhere to each other with different strengths depending on their types. Cell sorting results from random motions of the cells that allow them to minimize their configuration energy; this phenomenon is analogous to the surface-tension-driven phase separation of two immiscible liquids. If cells of the same type adhere more strongly, they gradually cluster together, with less adhesive cells surrounding the more adhesive ones. Differential adhesion results from differences (controlled at the subcellular level) in the expression of adhesion molecules on cell membranes, which may vary both in quantity and identity (Oberlender & Tuan 1994; Tsonis et al. 1994).

Based on the physics of the DAH, we model adhesive phenomena as variations in cell-specific adhesivity at the cell level, rather than at the level of individual molecules and their interactions. Simple thermodynamics then accounts for the macroscopic behaviour of cell mixtures at the scale of cell aggregation into tissues.

4.1.2 The extended CPM framework

Glazier & Graner's original CPM provided a physical formalism for studying the implications of the DAH (Glazier & Graner 1993). The CPM generalizes the Ising model, and shares the Ising model's core idea of modelling dynamics based on energy minimization under imposed fluctuations. As long as we can describe a process in terms of a real or effective potential energy, we can include it in the CPM framework by adding it to the other terms in the energy. We extend the original CPM framework to (i) model haptotaxis by adding an extra chemical potential term to the original CPM energy, (ii) include time variation in the adhesivity of cells, (iii) accommodate cell growth and (iv) provide a phenomenological mechanism for cell division (mitosis).

4.1.3 Modelling living cells and ECM (discrete representation on a grid)

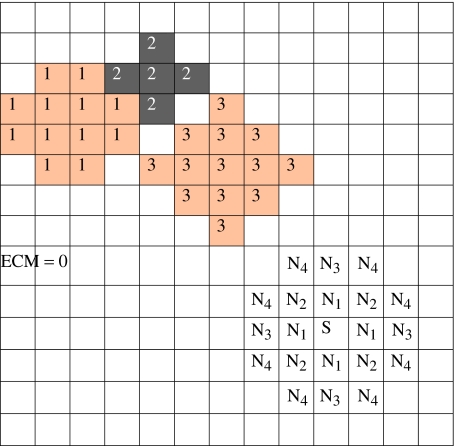

The CPM uses a lattice to describe cells. We associate an integer index to each lattice site (voxel) to identify the space a cell occupies at any instant (figure 4). The value of the index at a lattice site (i, j, k) is σ if the site lies in cell σ. Domains (i.e. collection of lattice sites with the same index) represent cells. Thus, we treat a cell as a set of discrete subcomponents that can rearrange to produce cell motion and shape changes. Figure 4 shows three cells and the ECM, which require four distinct indices.

Figure 4.

The CPM grid and representation of cells and ECM. The shading denotes the cell type. Different cells (e.g. cells 1 and 3) may be of the same cell type. We also show the fourth-neighbour interactions of voxel S on a two-dimensional grid.

We model ECM as a set of generalized cells with distinct indices, unless a specific component of the ECM requires more detailed modelling (e.g. fibronectin, §4.3).

We model some cell behaviours on the lattice employed by the CPM, but others, which have different dynamics, require modelling outside the CPM framework. Growth and division are examples of cell behaviours that we describe on the CPM grid, but require additional dynamics or conditions. Cell differentiation requires modelling the gene regulatory network, which controls the CPM parameters; it requires a separate, microscopic submodel, and integration into the hybrid environment.

To model cell dynamics, the CPM uses an effective energy, E, which consists of true energies (e.g. cell–cell adhesion) and terms that mimic energies (e.g. the response of a cell to a chemotactic gradient). Cells evolve under strong damping. The dynamics penalizes disconnected domains of lattice sites with the same index. Several investigators have used the CPM to reproduce the behaviour of cell aggregates of different kinds in two dimensions and three dimensions (Upadhyaya 2000; Marée & Hogeweg 2001; Ouchi et al. 2003).

4.1.4 Dynamics of cell rearrangement

In mixtures of liquid droplets, thermal fluctuations of the droplet surfaces cause diffusion (Brownian motion), leading to minimization of surface energy. We model membrane fluctuations as simple thermal fluctuations. The fluctuations drive the cells' configuration to a global energy minimum, rather than to one of the multiple local minima of energy that can coexist. We phenomenologically assume that an effective temperature, T, drives cell membrane fluctuations. T defines the size of the typical fluctuation. We implement fluctuations using the Metropolis algorithm for Monte-Carlo Boltzmann dynamics (Glazier & Graner 1993; Zeng et al. 2003). If a proposed change in lattice configuration (i.e. a change in the indices associated with the voxels of the lattice) produces a change in effective energy, ΔE, we accept it with probability:

| (4.1) |

where k is a constant converting T into units of energy.

E includes terms to describe each mechanism we have decided to include, e.g.

| (4.2) |

We describe each of these terms below.

4.1.5 Cell–cell adhesion

In equation (4.2), Econtact phenomenologically describes the net adhesion/repulsion between two cell membranes. It is the product of the binding energy per unit area, , and the area of interaction of the two cells. In our model, depends on the specific properties of the interacting cells.

| (4.3) |

where the Kronecker delta, δ(σ, σ′)=0 if σ≠σ′ and δ(σ, σ′)=1 if σ=σ′, ensures that only links between surface sites in different cells contribute to the cells' adhesion energy. The adhesive interactions operate over a prescribed range around each lattice site. Figure 4 shows a fourth-nearest-neighbour interaction range. In two dimensions, each lattice site has four nearest neighbours. In three dimensions, the number of nearest neighbours is six.

4.1.6 Cell size and shape fluctuations

A cell of type τ has a prescribed target volume v(σ, τ) and target surface area s(σ, τ) corresponding to the averages for cell-type τ. The actual volume and surface area fluctuate around these target values, e.g. owing to changes in osmotic pressure, pseudopodal motion of cells, etc. Changes also result from growth and division of cells during morphogenesis. Evolume enforces these targets by exacting an energy penalty for deviations. Evolume depends on four model parameters: volume elasticity, λ, target volume, vtarget(σ, τ), membrane elasticity, λ′, and target surface area, starget(σ, τ):

| (4.4) |

Changing the ratio of to starget(σ, τ) changes the rigidity or floppiness of the cell shape. In our sample simulations, we drop the surface area term (see table 3, which lists parameter values) by setting λ′σ to zero.

Table 3.

Values of parameters for normal limb simulations.

| RD equations with stabilizing cubic terms | |

| domain length | 2π |

| domain width | 6π/7 |

| γ | 100.0 (humerus region), 180.0 (radius+ulna), 1710.0 (digits) |

| J 0 | 0.04 |

| k a | 1.0 |

| k i | 1.0 |

| R 0 | 2.0 |

| D | 5.0 |

| dax=dix | 1.0 in humerus (1 skeletal element) region |

| 1/4 in radius+ulna (2 skeletal elements) region | |

| 1/12 in digits (3 skeletal elements) region | |

| day=diy | 0.15 |

| ba/(γR0) | 0.02 |

| bi/(γR0) | −0.6 |

| c as | 1.32494 |

| c is | 0.86545 |

| Δx | π/35 |

| Δt | 0.000 02 |

| CPM parameters | |

| fluctuation temperature T | 1.5 |

| J (non-condensing) | 7.0 |

| J (condensing) | up to 0.5 |

| volume param., λσ | 3.0 |

| target volume, vtarget | 16 voxels, grows to 32 voxels before mitosis |

| surface param., λσ | not used (0) |

| haptotaxis param., μ | 50.0 |

| initial cell density | ∼60% |

| fibronectin parameters | |

| fibronectin production rate | 0.15 per time-step |

| TGF-β threshold | 0.15 |

| integration, grid and numerics parameters | |

| domain discretization | number of subdivisions in (X, Y, Z)=(71, 31, 211), corresponds to dorsoventral:antero-posterior:proximo-distal=2.3 : 1 : 6.8. A rectangular approximation to a typical limb bud is X=3.1 mm, Y=1.6 mm, final Z length after growth=10.8 mm (1.9 : 1 : 6.8). Same grid size used for CPM and RD. Approximately 2 65 000 voxels were initialized to cell indices |

| time-steps | 100 RD steps per CPM step, 71×31×211 trials per CPM step |

| total time | day 4 to day 7 (total of 3 days) covering stages 20–30 of chick limb growth. Total time-steps=300 CPM steps |

| domain growth | growth was uniformly distributed over a total of 300 CPM steps (the total time entry above) |

4.1.7 Chemotaxis and haptotaxis

In principle, cells can respond to both diffusible chemical signals and insoluble ECM molecules by moving along concentration gradients of these substances. Although CompuCell3D readily accommodates chemotaxis, mesenchymal cells in the developing limb seem not to respond chemotactically to any of the molecules in our core genetic network. We therefore have not included chemotaxis in our simulations. Haptotaxis requires a representation of an evolving, spatially varying concentration field, and a mechanism linking the field to the framework for cell and tissue dynamics. The former depends on the particular ECM molecule (§§4.2 and 4.3). We denote the local concentration of the molecules in extracellular space by a scalar field , where x denotes the location in space. An effective chemical potential, μ(σ) models haptotaxis:

| (4.5) |

4.1.8 Cell growth, cell division and cell death

Equations (4.3)–(4.5) used the energy formalism of the CPM to model certain cell behaviours. We also use the CPM lattice to model cell growth, division and death. Cell growth and death affect the CPM model parameters vtarget(σ, τ) and starget(σ, τ). We model cell growth by allowing the values of vtarget(σ, τ) and starget(σ, τ) to increase with time at a constant rate. Growth properties depend on cell type (§4.4).

We can model programmed cell death (apoptosis) simply by setting the cell's target volume to zero. In a chicken limb (and other examples of non-webbed limbs) non-condensed cells between the digits die off, freeing the elements from one another. The spaces between the zeugopodal elements (radius and ulna, tibia and fibula) similarly undergo apoptosis. In this paper, since we do not consider the formation of tissues other than cartilage, we do not implement rules for cell death.

Cell division occurs when the cell reaches a fixed, type-dependent volume. We model division by starting with a cell of average size, vtarget=vtarget,average, causing it to grow at a constant rate until vtarget increases to 2vtarget,average, and splitting the dividing cell into two cells, each with a new target volume: vtarget/2. One daughter cell assumes a new identity (a unique value of σ). A breadth-first search selects the voxels which receive the new σ. The split is along a random, approximate cell diameter. The breadth-first algorithm (submodel 5 in table 1), does not require explicit calculation of diameter: it ensures that the voxels belonging to the two daughter cells, respectively, each form a connected domain of voxels with the same index.

4.2 Modelling molecular scales: reaction–diffusion equations

Turing (1952) introduced the idea that interactions of reacting and diffusing chemicals (usually of two species) could form self-organizing instabilities that provide the basis for biological spatial patterning (e.g. animal coat patterning; see Murray 1993; Miura & Maini 2004a for reviews). A slow-diffusing activator (i.e. a chemical that has a positive feedback on its own production) and a fast-diffusing inhibitor can give rise to spatial patterns of high and low concentrations of activator. The key point is that the interaction of production and diffusion can destabilize spatially homogeneous reactant concentrations. RD systems develop concentration patterns via the Turing instability mechanism (§4.2.2). Several models attempt to account for RD of morphogenetic signalling during chondrogenesis in the limb (Newman & Frisch 1979; Hentschel et al. 2004) and its isolated mesenchymal tissue (Miura & Shiota 2000a,b; Miura et al. 2000; Miura & Maini 2004b). We use this continuum PDE-RD approach to model diffusible TGF-β in the limb domain.

Cell-type-specific gene expression programmes cause cells to respond to threshold levels of TGF-β concentration (see §4.3), forming a spatial pattern that reflects the established pattern of TGF-β concentration. TGF-β thus forms the first prepattern, which guides chondrogenic condensation.

In our RD model, the cells both affect and respond to the prepattern, rather than simply following it (Izaguirre et al. 2004). This feedback affects the stability of patterns, often helping to lock in (stabilize) a pattern that would be transient without feedback. The production of the substrate molecule fibronectin (described in §4.3), forms the second prepattern for cell condensation, which provides feedback and stability.

4.2.1 Reaction–diffusion continuum submodels

The general form for RD equations is

| (4.6) |

where i=1, …, M, u=(u1, …, uM)T, ui denotes the concentration of the ith chemical species, F=(F1, …, FM): RM→RM is the reaction term and γ>0 is an auxiliary parameter. Equation (4.6) applies to an open, bounded region Ω∈Rn, n≥1, with fixed or moving boundaries. is an M×n matrix of diffusion coefficients (with positive entries). We assume that the chemicals do not penetrate the boundary of Ω. That is, the boundary conditions we use are no-flux:

| (4.7a) |

where i=1, …, M, and is the unit outward normal to the boundary of Ω. In the isotropic case, the boundary conditions in equation (4.7a) simplify to:

| (4.7b) |

The initial conditions are:

| (4.8) |

For biological applications of RD see, among others, Meinhardt (1982), Murray (1993) and Miura & Maini (2004a). Often, as here, the number M of chemical species is two. Conventionally, u1 is an activator and u2 an inhibitor. Mathematically, the actions of activator and inhibitor mean that for a stationary steady state u0, we have if u1 is an activator and if u2 is an inhibitor. Commonly, we also assume that the inhibitor inhibits the activator and the activator activates the inhibitor ( and , respectively), but a bifurcation can also take place if the inhibitor activates the activator and the activator inhibits the inhibitor ( and ).

4.2.2 Turing bifurcation

Consider isotropic diffusion, when the entries of do not depend on j (we will later drop this restriction):

| (4.9) |

where u=(u1, u2)T and . Without loss of generality we can assume that

| (4.10) |

For simplicity, we also assume that Ω is a cuboid:

| (4.11) |

Let u0 be a spatially uniform solution of F(u)=0 stable to spatially homogeneous perturbations. Then, (see Grindrod 1991) u0 is also a stable solution of equation (4.9) if d is small. A Turing bifurcation occurs when, at the critical value of d=dcrit (for increasing, d, i.e. an increasing diffusion rate of inhibitor), u0 loses stability to a spatially varying stationary solution, generating a pattern (Alber et al. 2005). This pattern first grows exponentially, but the nonlinear terms in the reaction kinetics F typically slow down the growth and eventually lead to a steady-state pattern. The wavelength of the final pattern need not correspond to the maximally unstable wavelength of the linearized equations.

The geometry of the RD domain also helps determine the pattern. If the domain size and pattern scale are comparable, the shape and exact size of the domain have a crucial influence on the pattern. A central idea in explaining the emergence of different patterns in the avian limb through Turing-type RD mechanisms relies on this dependence. Newman & Frisch (1979) and Hentschel et al. (2004) suggested that variations in the width of the active zone might produce the different patterns corresponding to the stylopod, zeugopod and autopod.

In addition, if the RD domain has certain spatial symmetries (for example a cube, sphere, or more generally, a rectangle whose edge ratios are integers), different types of pattern are possible. In a two-dimensional rectangle with no flux boundary conditions, these patterns are horizontal or vertical stripes, or spots. Ermentrout (1991) has shown that stripes and spots cannot be simultaneously stable in this situation. Alber et al. (2005) have generalized this result to three dimensions and higher. Callahan & Knobloch (1996, 2001) have treated the case of periodic boundary conditions. The nonlinear (quadratic and cubic) terms in the RD equations determine whether stripes or spots (or neither) are stable. Changing the nonlinear terms in F can exchange stability between spots and stripes.

4.2.3 Application to modelling the avian limb

Chaturvedi et al. (2003) and Izaguirre et al. (2004) used an ad hoc Schnakenberg form (see Murray 1993) for F in equation (4.9) for their two-dimensional model of avian limb patterning. The RD equations in this earlier model acted autonomously, providing a prepattern to which the cells responded. Here, we use RD equations based on recent experiments on chondrogenesis in the early vertebrate limb and additional hypotheses which Hentschel et al. (2004) developed in a two-dimensional continuum context for the densities of different subtypes of mesenchymal cells and the activator-dependent production rates of activator and inhibitor. Cells produce the activator and inhibitor, which thus depend on cell density (Hentschel et al. 2004). This model reproduces in a two-dimensional version the periodicity and stripe patterns of a central longitudinal section of the real limb.

The RD equations based on Hentschel et al. (2004; corresponding to equations (4.15) therein), thus become:

| (4.12) |

Here, d represents the diffusion coefficients, and c the concentrations of diffusing species. The subscript ‘a’ denotes the activator, and subscript ‘i’ the inhibitor. Subscripts x, y and z denote the spatial variation of the diffusion coefficients (equivalent to varying the limb cross-section as we describe below).

R0 is the density of mobile cells in the continuum model (see Hentschel et al. 2004). Effectively, β(ca) denotes the fraction of R0 cells that produce the activator and inhibitor in equations (4.12) through the mechanism of Ja and Ji. In Hentschel et al. (2004), β corresponds to subtype R2 of type R0 (R2 cells express FGF-2 receptor 1). The proportion β(ca) depends on the TGF-β concentration, ca, owing to simplifications of more complicated equations (Hentschel et al. 2004). The crucial assumption which justifies the simplifications is that the overall mobile cell density changes slowly compared with the rate of cell differentiation (see Hentschel et al. 2004 for more details and a biological discussion of these simplifications). Section 4.4 describes the various cell types, their characteristics, and their transition rules in more detail, and also discusses our implementation of R0 and R2 cells.

In equation (4.12), we assume that the overall mobile cell density R0 is constant, effectively decoupling the RD dynamics from the cell dynamics and simplifying computation. In the range of interest of R0, the production of morphogens depends more on the rate constants and kinetic coefficients than on the cell density.

R2 cells secrete TGF-β and inhibitor at activator-dependent rates Ja(ca) and Ji(ca), respectively. We use Hill kinetics terms from Murray (1993) for these production rates (see also Hentschel et al. 2004). The functional forms are:

| (4.13) |

The constant production rate J0 of the activator is small compared with the term Ja(ca)β(ca).

The cells also produce activator and inhibitor via the two terms, Ka(ca)R0 and Ki(ci)R0, on the right-hand side of equations (4.12):

| (4.14) |

where subscript ‘s’ denotes stable-state values. Here, ψ(q) is a smooth step function with ψ(q)=1 for q near 1 and ψ(q)=0 for q≪1 and for q≫1, and ba and bi are constants. In the absence of experimentally justified reaction kinetics for the morphogen species, we want to limit the influence of the cubic terms. The modelling reason for the form we use for ψ is that it restricts the terms Ka(ca)R0 and Ki(ci)R0 to operate only near the equilibrium concentration. We have introduced extra terms, which change the nonlinear (cubic) terms in the Taylor expansion of the reaction kinetics F, to guarantee that the proximo-distal cross-sections of the patterns are spot-like rather than stripe-like, resulting in cylindrical bones8 (see also the discussion of the importance of nonlinear terms in §4.2.2 and Ermentrout 1991; Alber et al. 2005). For studies of the effect of cubic terms on patterning in other physical models, including Rayleigh–Bénard convection and superconductivity see Ginzburg & Landau (1950), Swift & Hohenberg (1977) and Bodenschatz et al. (2000). For a mathematical analysis of the stability of patterns in other specific RD systems in three dimensions (for example, the Brusselator and the Lengyel–Epstein model), see Callahan & Knobloch (1999, 2001).

Owing to the form of the terms Ka(ca) and Ki(ci), the terms with rates Ja(ca) and Ji(ca) dominate overall morphogen production both close to, and far from, equilibrium. Ka(ca) and Ki(ci) fine-tune the morphogen production rates to bias the emerging pattern to select spots rather than stripes in the proximo-distal cross-section, while the concentrations are still close to equilibrium.

Pattern periodicity in RD depends on the solution domain. This dependence is biologically realistic: in the chicken, the antero-posterior width of the limb bud remains approximately constant during pattern formation, as does the dorsoventral width (except near the tip), but the proximo-distal length of the apical and active zones vary with time (reviewed in Hentschel et al. 2004). Changing spatial domains are numerically problematic. Here, we simplify this problem by using changing diffusion coefficients (equations (4.12)), which is equivalent to changing the aspect ratio of the domain (see Newman & Frisch 1979). If L is a constant length, then the transformation x′=x/L leads to , so the diffusion coefficient transforms as d′=d/L2. For example, doubling one side length (L=2) is equivalent to dividing the corresponding diffusion coefficient by 22.

For a square domain, appropriately scaling the diffusion coefficients can produce different rectangular cross-sections in the forearm and digit areas. When incorporating the prepattern in CPM calculations, we scale back to physical space (corresponding to the lattice of the CPM model).

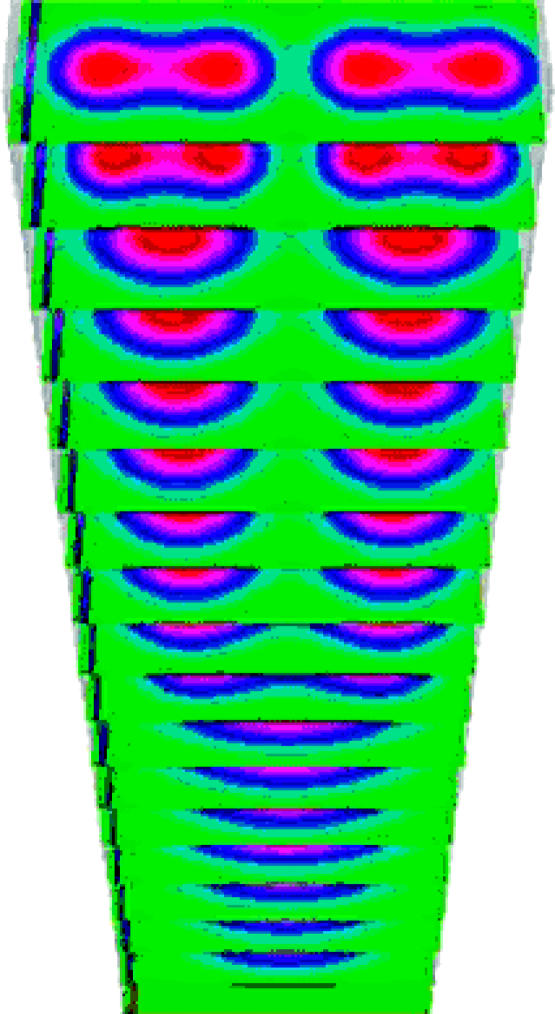

We have numerically solved the full three-dimensional equations (4.12). The stable cylindrical structures resemble bone elements (see figure 5 and §5). These structures provide a first template/prepattern, which couples with the stabilizing feedback mechanisms at the cell level, to result in chondrogenic patterning (§§4.3 and 4.4). We discretized equations (4.12) using an explicit finite-difference scheme over rectangular domains. Space and time discretization relate through standard stability criteria. Separately, or in combination, the set of parameters γ, the ratio lx/ly and the diffusion coefficients of the activator and inhibitor equivalently control the number of cylindrical elements and their geometries.

Figure 5.

Time-series of the concentration of the diffusible morphogen TGF-β for equations (4.12) (displayed along proximo-distal cross-sections) with time increasing along the distal direction (upwards). This first prepattern of cylindrically elongated parallel elements drives the final cell condensation through the mediating second prepattern of non-diffusing fibronectin. p denotes the proximal direction, v the ventral and a the anterior.

4.3 Modelling macromolecular scales: fibronectin secretion

Fibronectin secretion and assembly in the mesenchymal ECM (Wierzbicka-Patynowski & Schwarzbauer 2003) plays an important role in cell condensation. Our earlier two-dimensional simulations assumed that cells moved over a substratum coated with varying concentrations of non-diffusing fibronectin molecules (Chaturvedi et al. 2003; Izaguirre et al. 2004). In three dimensions, we still assume that fibronectin remains at its secretion location and use a separate grid to track its concentration. We could also model fibronectin on the CPM grid by making it into a generalized cell and adding appropriate CPM parameters like λ and J.

In our model, cells respond to the TGF-β chemical signal by producing fibronectin, and a cell–cell adhesion molecule (CAM) which we identify with N-cadherin (Oberlender & Tuan 1994; Tsonis et al. 1994) or cadherin-11 (Luo et al. 2005). Cells, in turn, bind to fibronectin and accumulate at points of high fibronectin concentration in this ECM microenvironment (Frenz et al. 1989; Zeng et al. 2003). Because cells tend to cluster at sites of high fibronectin concentration and deposit additional fibronectin there in proportion to their density, the trapping effect of fibronectin is self-enhancing. Furthermore, production of CAM in response to TGF-β signalling upregulates cell–cell adhesion, which also enhances the accumulation of cells.

Thus, although the TGF-β prepattern resulting from the Turing instability triggers patterning of fibronectin, self-enhancing, positive feedback, independent of TGF-β mechanisms, causes subsequent fibronectin deposition into patterns. Our proposal for a role for the adhesive substratum (e.g. fibronectin) in stability of the cellular patterns in our integrated model (see also Kiskowski et al. 2004) is qualitatively different from other RD-based approaches in the literature which seek stability only in the activator–inhibitor system itself. The fibronectin concentration pattern provides a prepattern for cell condensation. The model demonstrates global emergent phenomena resulting from local interactions.

4.4 Cell types and the state-transition model

During morphogenesis, cells differentiate from initial multipotent stem cells into the specialized types of the developed organism. The concept of differentiation requires some discussion (e.g. Newman & Forgacs 2005). Although every cell differs, identifying cells with broadly similar behaviours and grouping them as differentiation types is extremely convenient. Cell differentiation from one cell type to another is a comprehensive qualitative change in cell behaviour, generally irreversible and abrupt (e.g. responding to new sets of signals, turning on or off whole pathways). It typically depends on a gene expression programme generated during prior stages of development. All cells of a particular differentiation type share a set of descriptive parameters, while two different cell types (e.g. myoblasts and erythrocytes) have different parameter sets.

Cells of the same type can exist in different states, corresponding to a specific set of values for the cell-type's parameter set. A cell's behaviour depends on its state; two simulated cells behave identically in the same external environment if all parameters associated with their cell type are exactly the same, while cells of the same type with different parameter values can behave differently. Biologically, cells of the same type in different states typically differ less in their behaviour than cells of two different types. A cell's gene-expression programme, and the external cues that it encounters, influence both its type and state.

We model differentiation using a type-change map. Each type in this map corresponds to a cell type that exists during limb chondrogenesis. Change of a cell from one type to another corresponds to cell differentiation. The type-change map models regulatory networks by defining the rules governing type change, which account for the intra- and inter-cellular effects of chemical signals.

In the avian limb, the initial precartilage mesenchymal cells can translocate, divide and produce various morphogens and ECM molecules. We assume that cells in the active zone represent a cell type distinct from those in the apical zone. Specifically, unlike the apical-zone cells, active-zone cells respond to activator, inhibitor and fibronectin. They can also produce activator and inhibitor, and correspond to the R0 type in equations (4.12). Since β in equations (4.12) implicitly accounts for the R2 type, we do not include R2 cells in the type-change map. When a responsive cell in the active zone senses a threshold local concentration of activator (TGF-β), its type changes to fibronectin-producing. A fibronectin-producing cell can upregulate its cell–cell adhesion (the parameter in the CPM decreases). Cells that have not experienced local threshold levels of activator can respond to, but not produce, fibronectin. All cell types divide.

In total, we use four cell types in the model: apical-zone mesenchymal, active-zone mesenchymal, fibronectin-producing and quiescent (those in the frozen zone after the condensation has taken place).

4.5 The scale of the organ: integration of submodels

The various biological mechanisms must work in a coordinated fashion. We therefore designed our computational environment to integrate the biological submodels, while maintaining their modularity, e.g. by:

matching the spatial grid for RD and the CPM;

defining the relative number of iterations for the RD and CPM evolvers.

The fibronectin and CAM submodels form a positive feedback loop (of fibronectin secretion and CAM upregulation) providing the biologically motivated interface between the RD-based TGF-β prepattern and the CPM-based cell dynamics. TGF-β, the threshold concentration of which initiates differentiation (type change), provides the interface between RD and the type-change map. The type-change map chooses parameter sets and their values in the CPM representation.

4.6 Environment implementation: modular framework and integration

The front and back ends of the environment are distinct modules. The back-end consists of two engines that carry out most calculations—a computational engine, which combines the various biological submodels, and a visualization engine for graphics that can run independently. The front end to the engines provides a file-based user-interface for simulation parameters and visual display. The computational engine has three main modules: the CPM engine (stochastic, discrete), the RD engine (continuum PDEs) and the type-change engine (a rule-based state automaton).

The RD engine uses an explicit solver, based on forward time marching. We store these calculations as fields, e.g. the TGF-β, inhibitor and fibronectin concentrations. The CPM simulator implements the lattice abstraction and the Monte Carlo procedure. The acceptance probability function is Metropolis–Boltzmann. We can view the CPM as an operation on a field of indices. Various fields can evolve under their own sets of rules—Metropolis dynamics for the field of indices, RD for the field of morphogens. A chemical like fibronectin, which cells secrete and which then remains in place, is another concentration field, with a reaction dynamics with no diffusion. A version of this environment, CompuCell3D, is available for download. (For the detailed design of the computational algorithms and environment see Cickovski et al. in press.)

In order to integrate these modules, we specify criteria for interpolating between the various grids and the order in which to evolve fields. Other sub-modules implement different cell responses, e.g. cell growth and mitosis. We used the Visualization ToolKit (VTK), available as freeware9 to develop our visualization software.

5. Discussion of simulation results

How do parameters affect the integrated model? We start with an initial distribution of undifferentiated cells in the ECM, with a cell volume less than the average cell volume (table 1), no initial fibronectin and a small, randomly perturbed, distribution of activator and inhibitor. We started with all cells as mesenchymal cells (with no frozen zone initially). We did not track the number of cells of specific types during the course of the simulation. The combination of morphogens, cell dynamics and cell differentiation produces the approximately periodic pattern of the major chondrogenic elements in the chick limb. Table 2 lists the important mechanisms and their corresponding control parameters to emphasize that, although the integrated model has a large number of parameters, only a few specific parameters control each mechanism.

We first present a parameter set for normal patterning of chick forelimb precartilage condensation: one followed by two and then three primary parallel skeletal elements successively in the distal direction. Figure 5 shows a time-series (in the growing distal direction) for the activator concentration as the first prepattern forms. Cells exposed to an above-threshold activator concentration begin and continue to secrete fibronectin. In response to fibronectin, cells undergo haptotaxis and become more adhesive to each other so the fibronectin concentration (the second prepattern) and cell-condensation (skeletal element) pattern follow the activator prepattern.

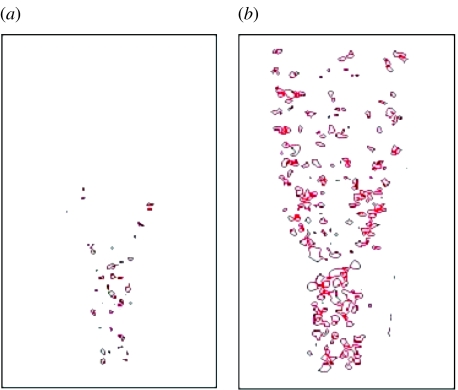

Fibronectin produces a positive feedback loop that stabilizes cell condensations. Figure 6 shows the distribution of fibronectin in the limb at different times. The fibronectin pattern forms relatively quickly (approximately 20 times faster than the final cell condensations, see figure 6 and its caption). Figure 7 shows10 simulations of the full three-dimensional chick-limb chondrogenesis model, where the cells have condensed into the chondrogenic pattern of a chick forelimb. Table 3 gives the complete set of parameter values for these simulations. Most of these parameters are analytically and numerically determined. Order-of-magnitude estimates exist in the literature for relevant quantities, such as the morphogen diffusion coefficients given in Lander et al. (2002). The range of parameter values studied should encourage more quantitative experiments. Parameters specific to the RD part of the model with cubic terms correspond to equations (4.12).

Figure 6.

Fibronectin production corresponding to normal chondrogenesis. We show fibronectin accumulation along the distal direction, as time progresses and the limb grows. Haptotaxis of cells in response to fibronectin (the second prepattern) and cells continuing fibronectin secretion make the pattern robust and does not require a persistent activator (first) prepattern. The fibronectin pattern establishes itself faster (a) 400 Monte Carlo steps (half-formed limb); (b) 800 Monte Carlo steps (fully formed limb) than the final cell condensations (1040 Monte Carlo steps; figure 7), emphasizing fibronectin's role in pattern consolidation. Fibronectin accumulates at its secretion location: its concentration in the humerus region in (b) is larger than in (a).

Figure 7.

Cell condensation into humerus, ulna and radius, and digits after 1040 Monte Carlo steps. Visualization using volume rendering. The axes correspond to the p, a and v of figure 5.

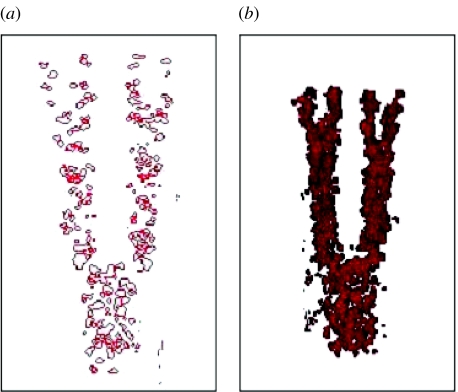

We next studied parameter sets resulting in two cases of abnormal development.

Figure 8 shows a case where four rather than three digits formed, corresponding to polydactyly. All parameters are the same as for normal development (table 3), except that the transition of dax=dix to the value of 1/12 occurs later than normal, e.g. owing to abnormal FGF signalling and/or late response of the cells secreting morphogens at the proximal boundary of the apical zone. Figure 9a displays the fibronectin distribution and figure 9b the resulting cell condensations. Experimentally, late, localized removal of the AER, a major source of the limb's FGF (and the only one in our model), induces ectopic digits in interdigital mesenchyme (see Hurle & Gañan 1987).

Figure 8.

Time-series (successive transverse cross-sections in the distal direction, which is upward in the figure) of TGF-β concentration in a growing limb bud, corresponding to the pathology of extra digits (four digits form instead of three; see figure 9).

Figure 9.

(a) Fibronectin distribution and (b) cell condensation, after 940 Monte Carlo steps, corresponding to the TGF-β (first) prepattern in figure 8.

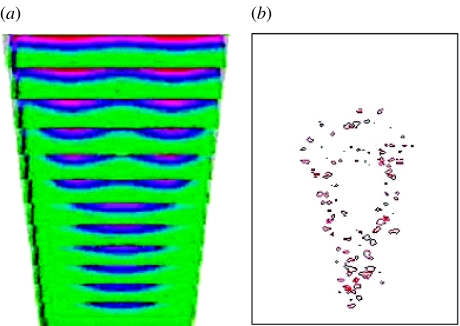

Figure 10 shows a case of fused skeletal elements, corresponding in certain respects to the pathology of the human genetic condition known as Apert's syndrome described in Cohen & Kreiborg (1995). Figure 10a shows the TGF-β prepattern along the distally growing limb bud. In the proximal region, the one-cylinder pattern (one spot in transverse section) is stable, followed by a bifurcation of the solution into two cylindrical elements (two spots in cross-section). The two elements then fuse into one long stripe in the transverse section. Figure 10b displays the corresponding fibronectin pattern. We obtained this pathology by setting dax=dix=1/14 in the digits (the three-skeletal-element region) instead of 1/12 (see table 3), and having the transitions in dax and dix occur later than normal, e.g. owing to an abnormal limb-cross-section aspect ratio or abnormal FGF signalling. Significantly, Apert's syndrome results from aberrant FGF signal transduction owing to an abnormal FGF receptor (Wilkie et al. 1995).

Figure 10.

(a) Time-series (successive transverse cross-sections in the distal direction) of the TGF-β concentration in a growing limb bud, corresponding to the pathology of Apert's syndrome. (b) The fibronectin concentration field after 500 Monte Carlo steps (limb not fully formed). The radius and ulna fuse and digits fail to form.

The two pathological cases suggest that domain-size changes in the apical and active zones, which we implemented a priori, affect the location and periodicity of skeletal element condensations. A more complete model, which we are currently developing, would employ the FGF signalling from the AER to control the evolution of the apical and active zones, Hox and Gli3 transcription factor gradients to control limb shape, and gradients of morphogens such as Sonic hedgehog and Wnt-7A to control antero-posterior and dorso-ventral patterning (reviewed in Tickle 2003).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from NSF Grants IBN-0083653, IBN-0344647 and ACI-0135195, NASA Grant NAG 2-1619, the IUB Pervasive Technologies Laboratories and an IBM Innovation Institute Award.

Footnotes

Present address: AgResearch Limited, Ruakura Research Centre, East Street, Hamilton, New Zealand.

We have effectively decoupled the RD prepattern (the first prepattern) from the cell dynamics by setting the cell density R0 constant and equal to the average cell density as a zeroth approximation to the interface between the CPM-based cell dynamics and RD-based activator and inhibitor dynamics. Including a further feedback mechanism from the cell to the RD prepattern, for example by computing instantaneous local cell density from the CPM, might obviate the additional third-order terms Ka(ca) and Ki(ci).

Note on visualization: shading of the cell condensations in figures 7 and 9 is due to the rendering algorithm (the VTK library's (footnote 9) volume rendering was used (see the legend of figure 7)). The algorithm does not render each cell of the condensation, which would be impractical in three dimensions. Spatial scales in all figures are uniform. Cells throughout the limb domain all have approximately the same volume in the figures.

References

- Alber M, Glimm T, Hentschel H.G.E, Kazmierczak B, Newman S.A. Stability of n-dimensional patterns in a generalized Turing system: implications for biological pattern formation. Nonlinearity. 2005;18:125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenschatz E, Pesch W, Ahlers G. Recent developments in Rayleigh–Benard convection. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2000;32:709–778. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan T.K, Knobloch E. Pattern formation in three-dimensional reaction-diffusion systems. Physica D. 1999;132:339–362. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan T.K, Knobloch E. Long wavelength instabilities of three-dimensional patterns. Phys. Rev. E. 2001;64:036214. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.64.036214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi R, et al. Multi-model simulations of chicken limb morphogenesis. In: Sloot P.M.A, Abramson D, Bogdanov A.V, Dongarra J.J, Zomaya A.Y, Gorbachev Z.E, editors. Computational Science—ICCS 2003: International Conference. Proceedings, Part III. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. vol. 2659. Springer; New York: 2003. pp. 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Cickovski T, Huang C, Chaturvedi R, Glimm T, Hentschel H.G.E, Alber M, Glazier J.A, Newman S.A, Izaguirre J.A. A framework for three-dimensional simulation of morphogenesis. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. In press. doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2005.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M.M, Jr, Kreiborg S. Hands and feet in the Apert syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1995;57:82–96. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320570119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downie S.A, Newman S.A. Different roles for fibronectin in the generation of fore and hind limb precartilage condensations. Dev. Biol. 1995;172:519–530. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.8068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermentrout B. Stripes or spots? nonlinear effects in bifurcation of reaction-diffusion equations on the Square. Proc. R. Soc. A. 1991;434:381–417. [Google Scholar]

- Frenz D.A, Jaikaria N.S, Newman S.A. The mechanism of precartilage mesenchymal condensation: a major role for interaction of the cell surface with the amino-terminal heparin-binding domain of fibronectin. Dev. Biol. 1989;136:97–103. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenz D.A, Akiyama S.K, Paulsen D.F, Newman S.A. Latex beads as probes of cell surface-extracellular matrix interactions during chondrogenesis: evidence for a role for amino-terminal heparin-binding domain of fibronectin. Dev. Biol. 1989;136:87–96. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90132-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehris A.L, Stringa E, Spina J, Desmond M.E, Tuan R.S, Bennett V.D. The region encoded by the alternatively spliced exon IIIA in mesenchymal fibronectin appears essential for chondrogenesis at the level of cellular condensation. Dev. Biol. 1997;190:191–205. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginzburg V.L, Landau L.D. On the theory of superconductors. Soviet Phys. JETP. 1950;20:1064. [Ginzburg, V. L. & L. D. Landau (1950), Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 20, 1064.] [Google Scholar]

- Glazier J.A, Graner F. A simulation of the differential adhesion driven rearrangement of biological cells. Phys. Rev. E. 1993;47:2128–2154. doi: 10.1103/physreve.47.2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graner F, Glazier J.A. Simulation of biological cell sorting using a 2-dimensional extended Potts model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992;69:2013–2016. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.69.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinrod P. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1991. Patterns and waves. [Google Scholar]

- Hall B.K, Miyake T. All for one and one for all: condensations and the initiation of skeletal development. Bioessays. 2000;22:138–147. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200002)22:2<138::AID-BIES5>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentschel H.G.E, Glimm T, Glazier J.A, Newman S.A. Dynamical mechanisms for skeletal pattern formation in the vertebrate limb. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2004;271:1713–1722. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurle J.M, Gañan Y. Formation of extra-digits induced by surgical removal of the apical ectodermal ridge of the chick embryo leg bud in the stages previous to the onset of interdigital cell death. Anat. Embryol. Berl. 1987;176:393–399. doi: 10.1007/BF00310193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izaguirre J.A, et al. CompuCell, a multi-model framework for simulation of morphogenesis. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1129–1137. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Levine H, Glazier J.A. Possible cooperation of differential adhesion and chemotaxis in mound formation of Dictyostelium. Biophys. J. 1998;75:2615–2625. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77707-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerszberg M, Changeux J.-P. A simple model of neurulation. BioEssays. 1998;20:758–770. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199809)20:9<758::AID-BIES9>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiskowski M, Alber M, Thomas G.L, Glazier J.A, Bronstein N.B, Pu J, Newman S.A. Interplay between activator-inhibitor coupling and cell–matrix adhesion in a cellular automaton model for chondrogenic patterning. Dev. Biol. 2004;271:372–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander A.D, Nie Q, Wan F.Y. Do morphogen gradients arise by diffusion? Dev. Cell. 2002;2:785–796. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard C.M, Fuld H.M, Frenz D.A, Downie S.A, Massagué J, Newman S.A. Role of transforming growth factor-β in chondrogenic pattern formation in the embryonic limb: stimulation of mesenchymal condensation and fibronectin gene expression by exogenenous TGF-β and evidence for endogenous TGF-β like activity. Dev. Biol. 1991;145:99–109. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90216-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J.H. Fate maps and the pattern of cell division: a calculation for the chick wing-bud. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1975;33:419–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Kostetskii I, Radice G.L. N-cadherin is not essential for limb mesenchymal chondrogenesis. Dev. Dyn. 2005;232:336–344. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marée A.F.M, Hogeweg P. How amoeboids self-organize into a fruiting body: multicellular coordination in Dictyostelium discoideum. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:3879–3883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061535198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marée A.F.M, Hogeweg P. Modelling Dictyostelium discoideum morphogenesis: the culmination. Bull. Math. Biol. 2002;64:327–353. doi: 10.1006/bulm.2001.0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinhardt H. Academic Press; London: 1982. Models of biological pattern formation. [Google Scholar]

- Merks R.M.H, Newman S.A, Glazier J.A. Cell-oriented modelling of in vitro capillary development. In: Sloot P.M.A, Chopard B, Hoekstra A.G, editors. Cellular Automata: Proceedings 6th International Conference on Cellular Automata for Research and Industry, ACRI 2004, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 25–28, 2004. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. vol. 3305. Springer-Verlag; Heidelberg: 2004. pp. 425–434. [Google Scholar]

- Miura T, Maini P.K. Periodic pattern formation in reaction-diffusion systems: an introduction for numerical simulation. Anat. Sci. Int. 2004;79:112–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-073x.2004.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura T, Maini P.K. Speed of pattern appearance in reaction-diffusion models: implications in the pattern formation of limb bud mesenchyme cells. Bull. Math. Biol. 2004;66:627–649. doi: 10.1016/j.bulm.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura T, Shiota K. TGF β2 acts as an ‘activator’ molecule in reaction-diffusion model and is involved in cell sorting phenomenon in mouse limb micromass culture. Dev. Dyn. 2000;217:241–249. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200003)217:3<241::AID-DVDY2>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura T, Shiota K. The extracellular matrix environment influences chondrogenic pattern formation in limb micromass culture: experimental verification of theoretical models of morphogenesis. Anat. Rec. 2000;258:100–107. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(20000101)258:1<100::AID-AR11>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura T, Komori M, Shiota K. A novel method for analysis of the periodicity of chondrogenic patterns in limb bud cell culture: correlation of in vitro pattern formation with theoretical models. Anat. Embryol. (Berl.) 2000;201:419–428. doi: 10.1007/s004290050329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moftah M.Z, Downie S, Bronstein N, Mezentseva N, Pu J, Maher P, Newman S.A. Ectodermal FGFs induce perinodular inhibition of limb chondrogenesis in vitro and in vivo via FGF receptor 2. Dev. Biol. 2002;249:270–282. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J.D. 2nd edn. Springer; Berlin: 1993. Mathematical biology. [Google Scholar]

- Nellen D, Burke R, Struhl G, Basler K. Direct and long-range action of a DPP morphogen gradient. Cell. 1996;85:357–368. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman S.A. Lineage and pattern in the developing vertebrate limb. Trends Genet. 1988;4:329–332. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(88)90051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman S.A, Comper W.D. ‘Generic’ physical mechanisms of morphogenesis and pattern formation. Development. 1990;110:1–18. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman, S. A., Forgacs, G. In press. Complexity and self-organization in biological development and evolution. In Complexity in chemistry, biology and ecology (ed. D. Bonchev, D. H. Rouvray). New York: Springer.

- Newman S.A, Frisch H.L. Dynamics of skeletal pattern formation in developing chick limb. Science. 1979;205:662–668. doi: 10.1126/science.462174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlender S.A, Tuan R.S. Expression and functional involvement of N-cadherin in embryonic limb chondrogenesis. Development. 1994;120:177–187. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouchi N.B, Glazier J.A, Rieu J, Upadhyaya A, Sawada Y. Improving the realism of the cellular Potts model in simulations of biological cells. Physica A. 2003;329:451–458. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg M.S. Reconstruction of tissues by dissociated cells. Science. 1963;141:401–408. doi: 10.1126/science.141.3579.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg M.S. Goal-directedness in embryonic development. Integr. Biol. 1998;1:49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Swift J, Hohenberg P.C. Hydrodynamic fluctuations at the convective instability. Phys. Rev. A. 1977;15:319–328. [Google Scholar]

- Tickle C. Patterning systems-from one end of the limb to the other. Dev. Cell. 2003;4:449–458. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsonis P.A, Del Rio-Tsonis K, Millan J.L, Wheelock M.J. Expression of N-cadherin and alkaline phosphatase in the chick limb bud mesenchymal cells: regulation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and TGF-β1. Exp. Cell. Res. 1994;213:433–437. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turing A. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 1952;237:37–72. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyaya, A. 2000 Thermodynamic and fluid properties of cells, tissues and membranes. Ph.D. thesis, University of Notre Dame.

- Van Obberghen-Schilling E, Roche N.S, Flanders K.C, Sporn M.B, Roberts A.B. Transforming growth factor β1 positively regulates its own expression in normal and transformed cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:16 7741–16 7746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]