Abstract

Background and purpose:

Absorptive epithelia express apical receptors that allow nucleotides to inhibit Na+ transport but ATP unexpectedly stimulated this process in an absorptive cell line derived from human bronchiolar epithelium (H441 cells) whilst UTP consistently caused inhibition. We have therefore examined the pharmacological basis of this anomalous effect of ATP.

Experimental approach:

H441 cells were grown on membranes and the short circuit current (ISC) measured in Ussing chambers. In some experiments, [Ca2+]i was measured fluorimetrically using Fura -2. mRNAs for adenosine receptors were determined by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Key results:

Cross desensitization experiments showed that the inhibitory response to UTP was abolished by prior exposure to ATP whilst the stimulatory response to ATP persisted in UTP-pre-stimulated cells. Apical adenosine evoked an increase in ISC and this response resembled the stimulatory component of the response to ATP, and could be mimicked by adenosine receptor agonists. Pre-stimulation with adenosine abolished the stimulatory component of the response to ATP. mRNA encoding A1, A2A and A2B receptor subtypes, but not the A3 subtype, was detected in H441 cells and adenosine receptor antagonists could abolish the ATP-evoked stimulation of Na+ absorption.

Conclusions and implications:

The ATP-induced stimulation of Na+ absorption seems to be mediated via A2A/B receptors activated by adenosine produced from the extracellular hydrolysis of ATP. The present data thus provide the first description of adenosine-evoked Na+ transport in airway epithelial cells and reveal a previously undocumented aspect of the control of this physiologically important ion transport process.

Keywords: Airway epithelia, epithelial Na+ transport, Ussing chamber, adenosine receptors, P2Y2 receptor

Introduction

Virtually all polarized epithelia express apical receptors that allow nucleotides in the luminal fluid to control the transport of water and salts (see, e.g. Wong, 1988; Mason et al., 1991; Wilson et al., 1996; Ko et al., 1997; Ramminger et al., 1999; Leipziger, 2003). One of the most frequently documented such receptors is the P2Y2 receptor, which couples to phospholipase C/inositol-trisphosphate- (PLC/IP3) (see Berridge, 1993) and thus allows adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and uridine triphosphate (UTP) to increase intracellular free Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) (Nicholas et al., 1996). Studies of several different absorptive epithelia have shown that activation of these receptors leads to inhibition of Na+ transport (see e.g. Inglis et al., 1999, 2000; Ramminger et al., 1999; Cuffe et al., 2000; Kunzelmann and Mall, 2003; Kunzelmann et al., 2005) and, in the airways, these receptors appear to form part of a mechanism that allows autocrine control over the depth of airway surface liquid (Lazarowski et al., 2004). These observations suggest that P2Y2 receptor agonists might provide a means of treating the abnormally high rate of Na+ transport seen in lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis (CF), a lethal genetic disease (Yerxa et al., 2002; Leipziger, 2003; Kunzelmann and Mall, 2003). This prompted us to explore the effects of ATP and UTP upon Na+ transport and [Ca2+]i in a Na+ absorbing cell line derived from the human bronchiolar epithelium (H441, see e.g. Sayegh et al., 1999; Clunes et al., 2004; Ramminger et al., 2004). Although our data show that UTP inhibits Na+ absorption, ATP caused an unexpected stimulation of this process and, as P2Y2 receptors are equally sensitive to these nucleotides (Nicholas et al., 1996), an additional receptor must underlie this effect of ATP. The aim of the present study was therefore to establish the pharmacological basis of this unexpected effect of ATP.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Standard techniques were used to maintain stocks of H441 cells in Rosewell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS, 8.5%), newborn calf serum (NCS, 8.5%), glutamine (2 mM), insulin (5 μg ml−1), transferrin (5 μg ml−1), selenium (5 ng ml−1) and an antibiotic/antimycotic mixture (Sigma Chemical Co., Poole, Dorset, UK). For experiments, cells removed from the culture flasks using trypsin/ethylene diaminetetraacetic acid, were resuspended in standard culture medium and plated (∼106 cells cm−2) onto Costar Snapwells (Corning BV, Schipol-Rijk, The Netherlands). For experiments in which short-circuit current (ISC) and [Ca2+]i were measured simultaneously, these membranes were cut into small pieces that were glued to Perspex disks with 1 mm holes drilled through them to form small wells into which the cells were seeded (Ko et al., 1999). After ∼24 h, all cultures were gently washed to remove non-adherent cells and incubated (4–6 days) in medium identical to that described above, except that (i) FBS and NCS were replaced with FBS (8.5%) that had been dialysed against 150 mM NaCl to remove hormones and growth factors, and (ii) it contained 0.2 μM dexamethasone, a synthetic glucocorticoid that induces a Na+ absorbing phenotype in these cells (Sayegh et al., 1999; Clunes et al., 2004; Ramminger et al., 2004).

Standard electrometric measurements

Costar Snapwell membranes bearing confluent cells (see above) were mounted in Ussing chambers and bathed with physiological saline (composition in mM: NaCl, 117; NaHCO3, 25; KCl, 4.7; MgSO4, 1.2; KH2PO4, 1.2; CaCl2, 2.5 and D-glucose (pH 7.3–7.5), when bubbled with 5% CO2) that was maintained at 37°C and continuously circulated using gas lifts. The transepithelial potential (Vt) was initially monitored under open-circuit conditions and, once this stabilized (20–30 min), Vt was clamped at 0 mV (DVC 1000 voltage/current clamp, World Precision Instruments, Stevenage, Herts, UK), whereas the current needed to maintain this potential (ISC) was monitored and recorded (4 Hz) using a PowerLab interface (AD Instruments, Hastings, East Sussex, UK). Transepithelial resistance (Rt) was determined from the expression Rt=Vt/ISC. In some experiments, physiological saline was continually pumped through the apical and basolateral chambers so that applied drugs could subsequently be washed from the bath.

Simultaneous measurement of ISC and [Ca2+]i

Confluent cells (see above) were loaded with Fura-2 by incubation (∼40 min, 37°C) in medium containing the acetoxymethyl ester form (3 μM) of this Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent dye together with pluronic F127 (1.8 μM), a non-ionic detergent, and probenecid (2.5 mM), an inhibitor of organic cation extrusion systems. Confluent H441 cells accumulate little dye under standard conditions and so inclusion of these compounds was necessary for adequate dye loading. The Fura-2-loaded cells were mounted in a miniature Ussing chamber (Lazarowski et al., 1997; Ko et al., 1999) where the basolateral and apical sides of the cell layer were independently superfused (∼3 ml min−1, 37°C) with physiological saline (see above). Solenoid operated valves allowed these solutions to be independently and rapidly switched and, immediately before entering the chambers, the solutions passed through thermostatically controlled heaters to ensure that experiments were carried out at 37°C. The chamber was mounted on the stage of a Nikon inverted microscope equipped with extra long working distance fluorescence optics (Nikon CFI Plan Fluor ELWD, 0.6 numerical aperture) and a Cairn Research (Faversham, Kent, UK) Optoscan UV light source so that the cells could be alternatively illuminated at 340 and 380 nM. The intensity of fluorescence (510 nM) evoked by illumination at these two wavelengths (intensity of Fura-2 fluorescence signal evoked by excitation at 340 nM (F340) and intensity of Fura-2 fluorescence signal evoked by excitation at 380 nM (F380), respectively) was monitored and recorded (4 Hz) in parallel with ISC, which was recorded using a Physiologic Instruments (San Diego, CA, USA) VCC600 voltage clamp. A full account of this method is published elsewhere (Ko et al., 1999).

Acute changes in the ratio F340/F380 are often used as an indicator of [Ca2+]i, but such experiments are usually undertaken using cells plated onto glass coverslips, whereas confluent cells on membranes take up less dye than single cells and substantial amounts of light are scattered by the culture membrane, which substantially increases background fluorescence. Under these conditions, the fraction of F340 and F380 owing to background can be substantial and, as Fura-2 fluorescence will decline as the dye is bleached and/or extruded from the cell (Grynkiewicz et al., 1985), the relative contribution of this background will change throughout the experiments. To ensure that this did not confound analysis of the present data, at the end of each experiment the cells were exposed to thapsigargin (1 μM, bilateral), a substance that evokes a substantial rise in [Ca2+]i (see Thastrup et al., 1990). Once this rise was fully established, the cells were exposed to N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethane sulphonic acid-buffered saline containing 10 mM MnCl2. As the thapsigargin-activated Ca2+-influx pathway is Mn2+-permeable (e.g. Jacob, 1990), and as Mn2+ rapidly quenches Fura-2 fluorescence, this causes a rapid fall in F340 and F380. The Mn2+-resistant component of each signal was assumed to indicate the cation-insensitive background fluorescence present throughout the preceding experiment. Files encoding the raw data were transferred to a computer spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel) and the appropriate background values subtracted before the ratio F340/F380 was calculated.

Experimental design and data analysis

All drug applications were timed carefully so that individual records could be aligned and pooled to give overall ‘mean' traces that are shown as mean±s.e.m.; these manipulations were undertaken using the standard features of Microsoft Excel. As the spontaneous ISC recorded from different cell preparations could vary over a substantial range (5–50 μA cm−2), experiments were undertaken using strictly paired protocols in which the control and experimental cells were age matched and were at identical passage. The significance of differences between mean values was thus assessed using Student's paired t-test or one-way analysis of variance as appropriate. Experimentally induced changes in ISC and F340/F380 were determined, for individual experiments, by subtracting the values measured in unstimulated cells from the values measured during stimulation and are also presented as mean±standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Desensitization experiments were undertaken using a standard protocol in which the cells were exposed to the initial, desensitizing agonist for 10 min, and washed with physiological saline for 10 min before being stimulated a second time.

Isolation/analysis of RNA

RNA was isolated from cells (∼3 × 106) grown on Costar Transwell membranes (Corning BV, Schipol-Rijk, The Netherlands) using Trizol reagent (Gibco BRL, Paisley, UK) and aliquots (5 μg) of this RNA fractionated on formaldehyde/agarose/ethidium bromide gels and it was examined under UV light to ensure that significant degradation had not occurred. Separate aliquots (2 μg) were then transcribed into cDNA using M-murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (RT) (200 U μl−1) and excess (10 mM) dATP, dCTP, dGTP and dTTP. Aliquots of the resultant cDNA corresponding to 1 μg of RNA then served as templates in the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the primers detailed in Table 1. All such reactions took place in 50 μl of PCR buffer containing 1.5 mM Mg2+, 1 μM of the appropriate sense and antisense primers, and excess (200 μM) dATP, dCTP, dGTP and dTTP. Samples were first denatured at 95°C for 3 min and the PCR reaction then allowed to proceed through 40 denaturing (1 min at 95°C), annealing (1.5 min at the temperatures given in Table 1) and polymerization (2 min at 72°C) cycles followed by a final polymerization period (10 min) at 72°C. The resultant products were fractionated on agarose/ethidium bromide gels and their sizes determined by reference to known standards. Products were isolated from the gels and sequenced (ABI 3100 Genetic Analyser; Ninewells Hospital and Medical School DNA Analysis Facility, University of Dundee) to verify their origin. PCR reactions were also undertaken using (i) aliquots of extracted RNA that had not been exposed to RT, but which had otherwise been treated identically and (ii) aliquots of water containing neither DNA nor RNA. Moreover, to confirm that the failure to generate a particular product was not owing to a failure the RT-PCR process itself, all assays were run in parallel with control reactions using actin-specific primers.

Table 1.

Primers used in PCR reactions

| Target sequence | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Size (kb) | TA (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P2Y2 (NM002564) |

TCAATGGCACCTGGGATG |

ATGTCCTTAGTGTTCTCGGCT |

1.1 |

58 |

| A1 (NM000674) |

ATGCCGCCCTCCATCTCA |

CTAGTCATCAGGCCTCTCT |

0.98 |

60 |

| A2A (NM000675) |

ATCATGGGCTCCTCGGTGTA |

GGACACTCCTGCTCCA |

1.2 |

62 |

| A2B (NM000676) |

ATGCTGCTGGAGACACAGGA |

ACACCGAGAGCAGGTGTAC |

0.98 |

62 |

| A3 (NM000677) | ATGCCCAACAACAGCACT | TCAGAATTCTTCTCAAGCT | 0.96 | 54 |

Abbreviations: PCR, polymerase chain reaction; TA, annealing temperature.

The primers sequences were designed to generate PCR products specific to the listed receptor subtypes by reference to the gene sequences referenced by accession numbers given in parentheses. The table also lists the predicted sizes of the appropriate PCR products and TA.

Results

Verification of methodology

The mean values of Rt, ISC and Vt for cells mounted in standard Ussing chambers were 257.8±5.7 Ωcm2, 44.6±3.3 μA cm−2 and 11.7±1.1 mV, respectively (n>60), and these values differed from the equivalent data derived from Fura-2-loaded cells mounted in the miniature Ussing chamber (Rt: 387.5±14.8 Ωcm2; ISC: 10.5±0.5 μA cm−2; Vt: 4.5±0.3 mV, n>60). However, both data sets lie within the range of values previously reported for these cells (see also Sayegh et al., 1999; Lazrak and Matalon, 2003; Ramminger et al., 2004) and our experience is that there can be day-to-day variations in the magnitudes of these parameters. We therefore directly explored the effects of Fura-2 loading and of exposure to the solvent vehicle (0.1% dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO)) using a strictly paired protocol (n=6). These manoeuvres did not affect Rt (control: 191.7±12.0 Ωcm2, DMSO: 187.8±23.8 Ωcm2; Fura-2: 227.8±21.9 Ωcm2) or ISC (control: 28.2±2.9 μA cm−2; DMSO: 29.8±4.0 μA cm−2; Fura-2: 32.8±1.8 μA cm−2), but Fura-2 caused a small rise (P<0.05) in Vt (control: 5.3±0.4 mV, DMSO: 5.3±0.6 mV; Fura-2: 7.4±0.7 mV). Measurements made after 10 μM amiloride had been added to the apical bath revealed no effect upon the fraction of the spontaneous ISC that was inhibited by this Na+ channel antagonist (control: 90.4±3.2%, DMSO: 86.3±6.3%, Fura-2: 87.0±5.0%). Several of the compounds used in this study were insoluble in water and required the use of DMSO as a solvent vehicle. Preliminary experiments showed that cells tolerated 0.1% DMSO without detrimental effect, whereas higher concentrations led to a fall in ISC. The total DMSO concentration therefore did not exceed 0.1% (vol/vol) in any experiment.

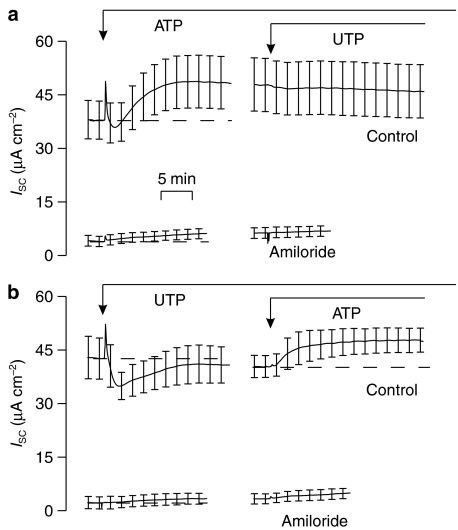

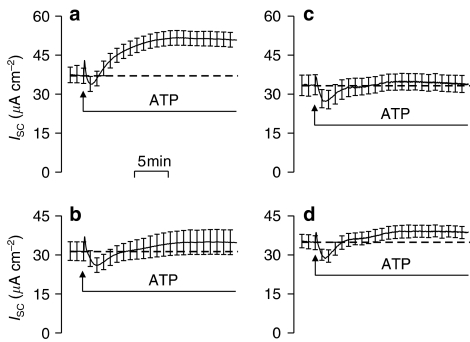

Effects of ATP and UTP upon ISC

Figure 1 shows the effects of adding 100 μM ATP (Figure 1a) or UTP (Figure 1b) to the apical solution. Initially, both nucleotides caused rapid increases in ISC, but these responses were transient and ISC had thus returned to its basal value within ∼3 min. In ATP-stimulated cells, this initial transient was followed by a second rise in ISC that developed more slowly, taking ∼10 min to reach a plateau value that was then maintained for at least 40 min (Figure 1a). In contrast, the initial response to UTP was followed by a progressive fall in ISC so that the current recorded after ∼5 min lay below the value measured at the onset of the experiments (Figure 1b). This inhibitory response was not maintained as the ISC slowly returned to its initial value over ∼10 min (Figure 1b). Approximately 30 min after the addition of the first nucleotide, a dose (100 μM) of the other nucleotide was applied. Thus, UTP was added to ATP-stimulated cells (Figure 1a) and ATP to UTP-stimulated cells (Figure 1b). Figure 1a shows that UTP had no discernible effect upon ISC across ATP-stimulated cells. Figure 1b, on the other hand, shows that prestimulation with UTP abolished the initial component of the response to ATP, but did not affect the second, slowly developing increase in ISC. Figure 1 also shows that apical amiloride (10 μM) reduced the recorded current to ∼15% of control and abolished the nucleotide-evoked changes in ISC (Figure 1a and b).

Figure 1.

Effects of ATP and UTP on ion transport (ISC) measured across cells mounted in standard Ussing chambers either under control conditions (n=4) or in the presence of 10 μM apical amiloride (n=3). (a) Changes in ISC induced by adding ATP followed by UTP (both 100 μM) to the apical solution. (b) Effect of adding UTP followed by ATP (both 100 μM). Data are mean±s.e.m.

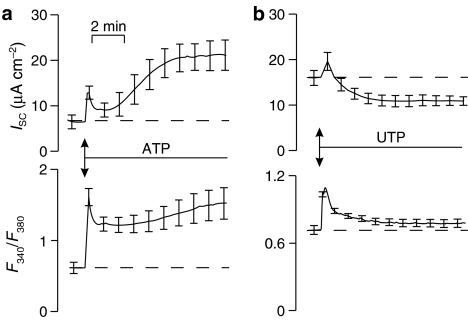

Effects of ATP and UTP upon ISC and F340/F380

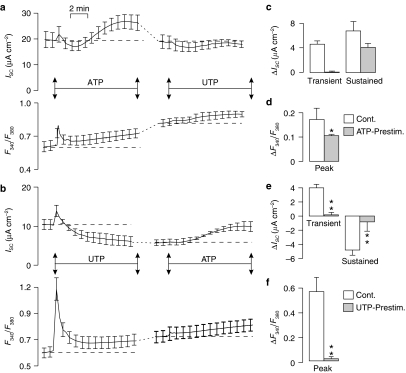

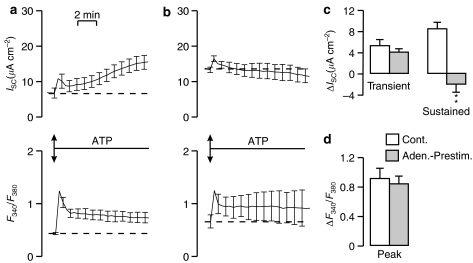

Figure 2a shows that the ATP-evoked changes in ISC described above are accompanied by a rise in F340/F380 that consists of an initial transient followed by a decline to a second more slowly developing increase. Similarly, the UTP-evoked changes in ISC are also accompanied by an increase in [Ca2+]i and, although these data suggest that this response is smaller than the corresponding response to ATP, this was not a consistent finding (see e.g. Figure 4). Neither nucleotide (ATP, n=6; UTP, n=4; both 100 μM) had a discernible effect upon ISC or F340/F380 when added to the basolateral solution. In subsequent experiments, cells were exposed to two pulses of apical ATP (100 μM) separated by a 10 min recovery period (see Materials and methods). The first such application evoked increases in ISC and F340/F380 similar to those described above and, while the second stimulus did evoke discernible increases in both signals, analysis showed that the initial, transient component of the electrometric response and the associated rise in [Ca2+]i were essentially abolished (Figure 3a and b). Moreover, while a slowly developing increase in ISC was evident, this was smaller than control (Figure 3a). Similarly, experiments in which cells were repeatedly stimulated with UTP (100 μM) showed that both components of the response to the second application of this nucleotide were greatly reduced (Figure 3c and d).

Figure 2.

Effects of ATP and UTP on ion transport (ISC) and Fura-2 fluorescence ratio (F340/F380) measured simultaneously. (a) Changes in the two parameters evoked by 100 μM ATP (n=33) (b) Effect of 100 μM UTP (n=22). Both signals are presented as mean±s.e.m.

Figure 4.

Effect of ATP followed by UTP (a, c and d) and UTP followed by ATP (b, e and f) on ISC and F340/F380 measured simultaneously. (a) and (b) show the time courses of the cross-desensitization experiments. The dashed lines represent a 10 min wash with control saline. Both the initial peak increase in ISC (‘Transient') and the increase after 10 min exposure to the nucleotide (‘Sustained') are shown (c and e). The peak increases in Ca2+ (ΔF340/F380) evoked by the first and second applications of nucleotide were also quantified (‘Peak'; d and f). All data are mean±s.e.m. (n=5) and asterisks denote statistically significant differences between the data derived from control and prestimulated cells (*P<0.05, **P<0.02).

Figure 3.

Effect of consecutive doses (100 μM apical) of ATP (a and b; n=5) and UTP (c and d; n=5) upon ISC and F340/F380 measured simultaneously. Both the initial peak increase in ISC (‘Transient') and the increase after 10 min exposure to the nucleotide (‘Sustained') are presented as mean±s.e.m. (a and c). The peak increases in Ca2+ (ΔF340/F380) evoked by the first and second applications of nucleotide were also quantified (‘Peak'; mean±s.e.m.; b and d) Asterisks denote statistically significant differences between the responses evoked by the first and second applications of nucleotide (*P<0.05, **P<0.002).

The responses to ATP and UTP are thus subject to autologous desensitization and subsequent studies explored the extent to which ATP and UTP could cause cross-desensitization. Figure 4a thus shows that prior stimulation with ATP essentially abolishes the UTP-evoked changes in ISC (Figure 4e) and F340/F380. Figure 4b, on the other hand, shows that prestimulation with UTP abolishes the initial transient component of the ATP-evoked rise in ISC (Figure 4c), attenuates the increase in F340/F380 (Figure 4d), but has no statistically significant effect upon the sustained increase in ISC (Figure 4c). A receptor population that does not desensitize during exposure to UTP thus underlies the sustained component of the response to ATP.

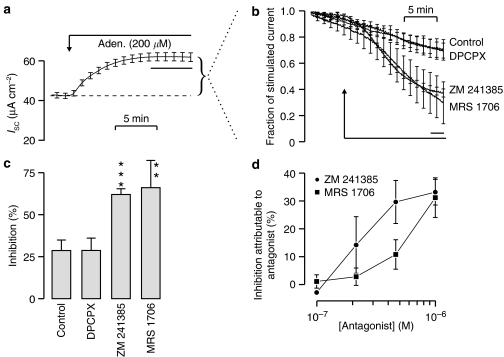

Effects of adenosine receptor antagonists upon the response to ATP

Figure 5 shows electrometric responses to ATP in control cells (a) and in cells that had been pretreated (20 min) with 4-(2-[7-amino-2-92-furyl)[1,2,4]triazolo[2,3-a][1.3.5]triazin-5-ylamino]ethyl)phenol (ZM 241385) (b) N-(4-acetylphenyl)-2-[4-(2,3,6,7-tetahydro-2,6-dioxo-1,3-dipropyl-1H-purin-8-yl)phenoxy]-acetamide (MRS 1706) (c) or 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine (DPCPX) (d; all 1 μM), compounds that all act as adenosine receptor antagonists. These substances did not affect basal ISC or the initial, transient component of the response to ATP (control: 6.3±1.5 μA cm−2; ZM 241385: 5.6±1.7 μA cm−2; MRS 1706: 2.7±0.7 μA cm−2; DPCPX: 4.7±1.5 μA cm−2), but reduced the second, more sustained component of this response. The effect of each antagonist was quantified by measuring the current recorded after 15 min exposure to ATP. This normally exceeded the basal ISC by 14.5±1.9 μA cm−2 and all of the tested antagonists significantly (P<0.05) inhibited this current (ZM 241385: 3.3±1.2 μA cm−2; MRS 1706: 1.1±1.1 μA cm−2; DPCPX: 4.4±1.3 μA cm−2). There were no statistically significant differences amongs the data derived from the antagonist-treated cells.

Figure 5.

Effect on ISC (mean±s.e.m.) of apical ATP (100 μM) under control conditions (a; n=7) and in cells that had been preincubated (20 min) in ZM 241385 (b; 1 μM, n=4), MRS 1706 (c; 1 μM, n=4), or DPCPX (d; 1 μM, n=4).

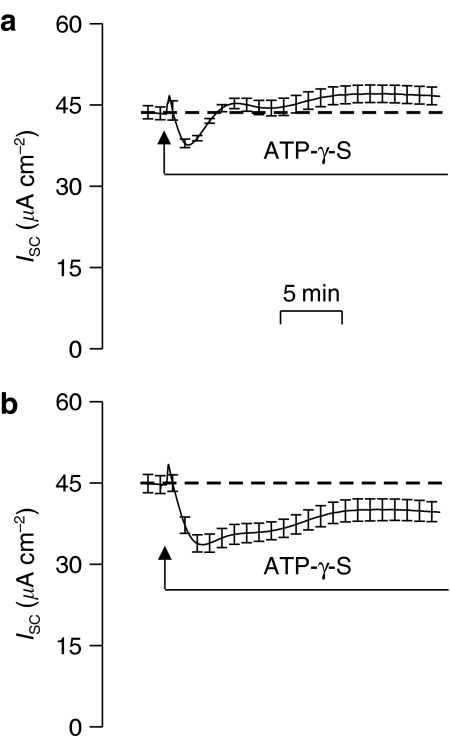

Effects of ATP-γ-S

Initial experiments (n=4) showed that ATP-γ-S caused a transient increase in ISC (ΔISC=6.6±1.8 μA cm−2) that was followed by a fall to a value below baseline that was reached after ∼5 min (ΔISC=6.3±2.7 μA cm−2), but gave way to a slowly developing stimulation so that the ISC recorded after 15 min exceeded the basal ISC by 8.4±1.0 μA cm−2. This response was thus very similar to that evoked by ATP itself (Figure 1). However, a different picture emerged from experiments undertaken using a second sample of ATP-γ-S, obtained from the same supplier but with a different batch number. The initial phases of this response were as described above (Figure 6a) but, in these experiments, the ISC recorded after 15 min exceeded the basal ISC by only 4.2±0.4 μA cm−2 and was thus smaller (P<0.05) than that described above. ZM 241385 (1 μM, 20 min preincubation) had no effect on the initial phases of the response to ATP-γ-S, but, under these conditions, the initial transient was followed by a sustained inhibitory phase and ISC remained below its basal level for the remainder of the experiment (Figure 6b). The purity of the second batch of ATP-γ-S used was assessed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (see Lazarowski et al., 2004). This analysis showed that a solution with a nominal ATP-γ-S concentration of 100 μM contained a substantial amount of adenosine diphosphate (ADP) (∼15 μM) and low levels of adenosine (∼0.01 μM), adenosine monophosphate (AMP) (∼0.1 μM) and ATP (∼0.3 μM). We did not analyse the first batch of ATP-γ-S used as we were unable to obtain a further sample.

Figure 6.

Effect of apical ATPγS (100 μM) on ISC. (a) Effect under control conditions and (b) Effect on cells that had been preincubated (20 min) in ZM 241385 (1 μM). Data are mean±s.e.m., n=4.

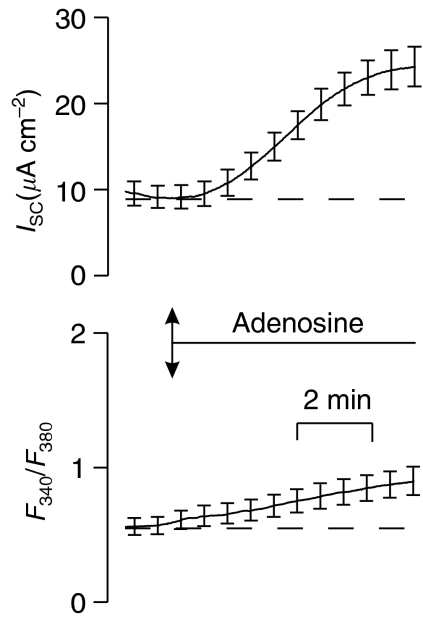

Effects of adenosine

Apical adenosine (200 μM) caused a slowly developing and sustained rise in ISC that became apparent after 2–3 min and reached a plateaux value after ∼8 min (Figures 7 and 10a). Examination of the simultaneously recorded values of F340/F380 showed that parameter rose slowly from 0.54±0.06 to 0.72±0.17 (P<0.05), demonstrating that this increase in ISC was accompanied by a modest increase in [Ca2+]i. However, this effect was not observed in all experiments and adenosine did not evoke rapid increases in F340/F380 like those seen during stimulation with ATP or UTP. Adenosine also increased ISC when added to the basolateral solution (basal ISC: 4.5±0.4 μA cm−2; adenosine-stimulated: 13.7±2.4 μA cm−2, n=4, P<0.01) and, qualitatively, this response was similar to that evoked by apical adenosine. Although F340/F380 appeared to rise slightly during stimulation with basolateral adenosine (basal F340/F380: 0.38±0.05; adenosine stimulated F340/F380: 0.55±0.009), this did not reach statistical significance. Experiments in which cells were successively exposed to two pulses of apical adenosine showed that the both stimuli caused significant (P<0.05 for both) increases in ISC, although the first response (ΔISC; 6.3±1.4 17.0±5.4 μA cm−2) was larger (P<0.05) than the second (ΔISC; 2.4±0.9 μA cm−2), indicating that the receptors underlying this response are subject to autologous desensitization. Although F340/F380 seemed to increase during both adenosine pulses, neither change reached statistical significance.

Figure 7.

Effects of apical adenosine (100 μM) upon ISC (upper panel) and F340/F380 (lower panel). Data are mean±s.e.m. (n=5).

Figure 10.

Effects of adenosine receptor antagonists on ISC. (a) Time course showing the effects of apical adenosine (200 μM) upon ISC (mean±s.e.m., n=20). Curved bracket indicates the adenosine-evoked increase in ISC, which was determined for each individual experiment. (b)The effects of DMSO solvent vehicle (control, n=5), DPCPX (1 μM, n=5), ZM 241385 (1 μM, n=5) and MRS 1706 (1 μM, n=5) on the adenosine-evoked increase in ISC. The bar indicates the period during which data were used to analyse inhibitory effects of the compounds. (c) The inhibitory effects of these compounds, presented as mean±s.e.m.; asterisks denote values that differ significantly from control (***P<0.0001, **P<0.002). (d) Results of experiments in which this protocol was used to quantify the inhibitory actions of different concentrations (0.1–1 μM) of ZM 1706 and of MRS 241385. The inhibitory effect of the solvent vehicle was monitored in each experiment so that could be corrected for the spontaneous/solvent-evoked fall in ISC.

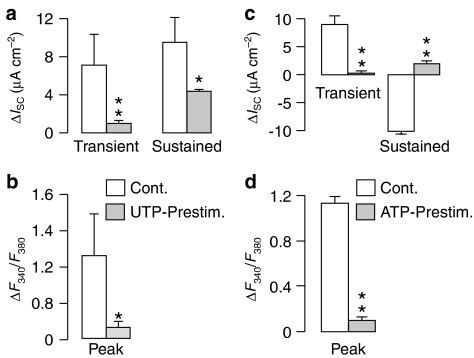

Desensitizing interactions between adenosine and ATP

Figure 8 shows ATP-evoked changes in ISC and F340/F380 measured in control and adenosine-prestimulated (100 μM, apical) cells. The control data (Figure 8a) confirm the ATP-evoked changes in ISC and [Ca2+]i described above and, although ATP also increased ISC in the adenosine-prestimulated cells (Figure 8b), the initial part of this response was normal, whereas the second, slowly developing component did not occur (Figure 8c). Prestimulation with adenosine had no effect upon the ATP-evoked increase in [Ca2+]i (Figure 8b and d). Further experiments showed that prestimulation with ATP reduced, but did not abolish the adenosine-evoked increase in ISC (control ΔISC: 15.2±5.3 μA cm−2; ATP-prestimulated ΔISC: 8.8±0.9 μA cm−2, n=5; P<0.01).

Figure 8.

Effect of adenosine on response to ATP. (a) Effect of ATP on ISC and F340/F380. (b) Effect of ATP on cells that had been stimulated with 100 μM apical adenosine and then washed with control saline for 10 min. (c) The initial peak increase in ISC (‘Transient') and the increase after 10 min exposure to ATP (‘Sustained'). (d) The peak increases in Ca2+ (ΔF340/F380) evoked by ATP (‘Peak'; d and f). All data mean±s.e.m. (n=5) and asterisks denote statistically significant differences between control and adenosine prestimulated cells (**P<0.02).

Ionic basis of the response to adenosine

Studies (n=4) of bi-laterally superfused epithelial cell layers (see Materials and methods) showed that apical amiloride (10 μM) rapidly reduced the spontaneous ISC from 26.9±6. 1 μA cm−2 to 4.4±1.3 μA cm−2 (P<0.001) and they established that this inhibitory effect was reversible, and thus the ISC recorded ∼10 min after amiloride had been washed from the bath (20.9±4.4 μA cm−2) did not differ from that measured at the onset of the experiments. Subsequent application of apical adenosine (200 μM) evoked a slowly developing rise in ISC and the ISC measured after ∼10 min (36.0±4.9 7 μA cm−2) exceeded (P<0.05) the basal value. Subsequent addition of apical amiloride (10 μM) reduced the ISC recorded from these cells to 6.1±1.4 μA cm−2 and analysis of these data showed that stimulation with adenosine had caused a substantial increase in amiloride-sensitive ISC (control: 22.5±5.7 μA cm−2; adenosine stimulated 29.9±4.3 7 μA cm−2; P<0.05). As such control over amiloride-sensitive ISC can reflect changes in apical Na+ conductance (GNa+) (see e.g. Morris and Schafer, 2002; Ramminger et al., 2004), we explored the effects of adenosine upon this parameter by measuring the apical membrane currents in basolaterally permeabilized cells exposed to an inwardly directed Na+ gradient (see Materials and methods). Initial measurements of intact cells (n=6) showed that apical adenosine (200 μM) increased ISC from 37.6±3.5 to 57.5±5.3 μA cm−2 (P<0.0005), and measurements made after permeabilization showed that GNa+ was 354.9±41.37 μS cm−2. This value is greater (P<0.001) than that measured in unstimulated cells (213.5±36.5 μS cm−2) at identical passage that generated 36.5±2.7 μA cm−2 of spontaneous ISC.

Pharmacological basis of the response to adenosine

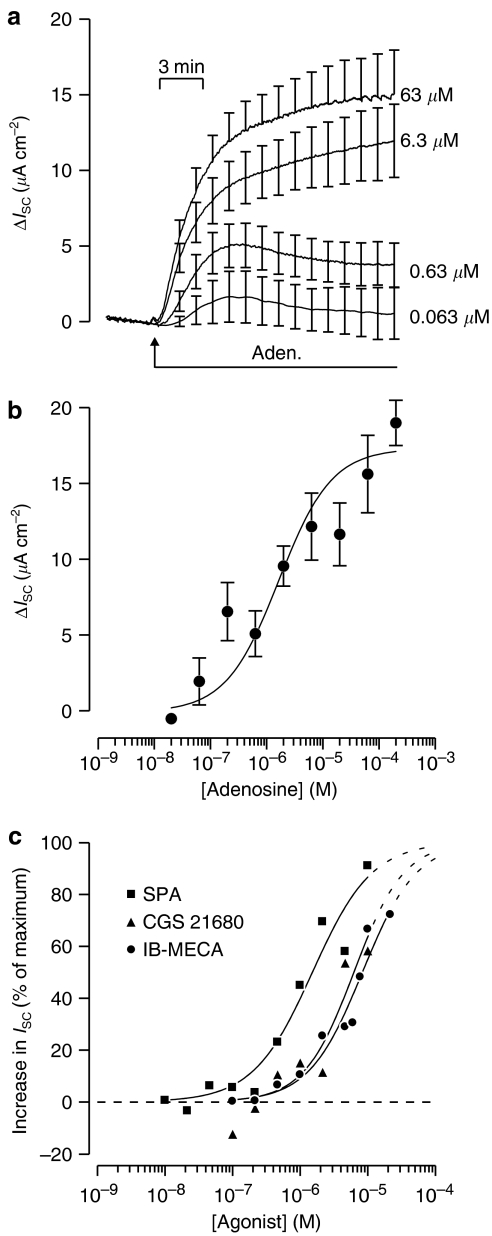

To characterize the receptors underlying the adenosine-evoked increase in ISC, we first attempted to construct cumulative concentration response curves by progressively raising the concentration of adenosine in the apical solution. However, although the cells consistently responded to adenosine, this approach was not fruitful as the responses to low concentrations developed slowly and it was very difficult to discern clear plateaux values as the concentration was increased. We therefore adopted an alternative strategy in which individual monolayers were exposed to only a single agonist concentration. Although this allows us to explore the pharmacological properties of the adenosine-sensitive receptors, variability between different monolayers, both in the basal ISC and in the magnitude of response to a given concentration of adenosine, imposed an unavoidable limitation upon the quality of the data that could be obtained in this way. The data in Figure 9, which were obtained in this way, thus show that the response to adenosine is concentration dependent. The adenosine-evoked increases in ISC measured in these experiments have been plotted against the concentration used in Figure 9b and show that the EC50 for this compound is 1.6±0.7 μM. Figure 9c shows the increases in ISC evoked by three adenosine analogues N6-(p-sulphophenyl)adenosine (SPA), 2-p-(2-carboxyethyl)-phenethylamino-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (CGS 21680) and N6-(3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5-N-methyluronamide (IB-MECA); the EC50 values for these compounds were 1.5±0.3, 8.4±0.9 and 6.2±1.5 μM, respectively. This analysis was undertaken by assuming that the tested drugs bind to a single site as effectively as adenosine (Figure 9), as the variability in the primary data (see above) meant that this simple model could not be distinguished from more complex schemes involving multiple binding sites.

Figure 9.

Effects of adenosine and adenosine receptor agonists upon ISC. (a) ISC was recorded during stimulation with apical adenosine: 0.063 μM, n=3, basal ISC=27.2±3.9 μA cm−2; 0.63 μM, n=7, basal ISC=33.4±3.8 μA cm−2; 6.3 μM n=7, basal ISC=25.7±5.4 μA cm−2; or 63 μM n=6, basal ISC=27.2±3.9 μA cm−2. All data are shown as mean±s.e.m. and the basal ISC (i.e. that measured before the addition of adenosine) was subtracted from all records in order to illustrate the adenosine-evoked changes in ISC. (b) The increases in ISC measured after ∼20 min exposure to apical adenosine (0.021–200 μM) were measured and plotted (mean±s.e.m.) against the concentration of adenosine used. (c) Cells were exposed to different concentrations of apical SPA, CGS 21680 or IB-MECA and the resultant increases in ISC measured and normalized to the response to a maximally effective concentration (200 μM) of apical adenosine measured in age-matched cells at identical passage. The results of this analysis are plotted against the concentration of agonist used; all data points are the mean values and error bars have been omitted in the interests of clarity. In all experiments, the cultured epithelial cell layers were each exposed to only a single concentration of agonist, and mean values derived from at least three independent experiments. The solid curves were fitted (least-squares regression) to the experimental data by assuming that the tested drugs bind to a single site as effectively as adenosine. Dashed lines denote extrapolation beyond the range of observed values.

Figure 10a shows that a maximally effective (200 μM) concentration of apical adenosine consistently evoked a sustained increase in ISC essentially identical to that described above. Once this response was established, these cells were exposed to DPCPX, ZM 241385 or MRS 1706 (all 1 μM), and Figure 10b shows the effects of these compounds upon the recorded ISC that was subsequently recorded from these cells. These data have been normalized to the adenosine-evoked increase in ISC measured in each experiment and thus show the changes in ISC that occur during exposure to these adenosine receptor antagonists or solvent vehicle (control). The ISC normally declines by ∼20% over the time scale of these experiments and DPCPX (1 μM) had no effect upon this spontaneous fall in ISC (Figure 10b). However, ZM 241385 and MRS 1706 accelerated this decline and analysis of these data confirmed that these compounds significantly reduced the adenosine-stimulated current (Figure 10c). Subsequent experiments indicated that these inhibitory effects were concentration dependent and, although ZM 241385 appeared slightly more potent, we could not discern an unambiguous difference between the effects of these compounds (Figure 10d).

Expression of mRNA encoding P2Y2 and adenosine receptors

RT-PCR-based analyses (see Materials and methods) showed that mRNA transcripts encoding the P2Y2, A1, A2A and A2B receptors were all expressed by in H441 cells that had been grown to confluence on permeable supports. However, reactions run using primers designed to amplify a sequence characteristic to the A3 receptor subfamily consistently failed to generate any such products, whereas parallel analyses using actin-specific primers confirmed that the assay procedure itself was working normally.

Discussion

Our initial studies confirmed (Sayegh et al., 1999; Lazrak and Matalon, 2003; Ramminger et al., 2004) that H441 cells spontaneously generate an ISC that is largely (∼85%) due to electrogenic Na+ absorption and established that loading the cells with Fura-2 had no major effect upon this process. Experiments in which the cells were exposed to ATP or UTP showed that these nucleotides controlled this transport process and increased [Ca2+]i, and the receptors underlying these responses appeared to be confined to the apical membrane. This was not altogether surprising as mRNA encoding the P2Y2 receptor, which is equally sensitive to ATP and UTP, was present and these receptors are found in the apical membranes of many polarized epithelia where they allow luminal nucleotides to increase [Ca2+]i by activating PLC/IP3 (Wong, 1988; Brown et al., 1991; Mason et al., 1991; Nicholas et al., 1996; Wilson et al., 1996, 1998; Inglis et al., 1999; Ramminger et al., 1999; Leipziger, 2003; Kunzelmann et al., 2005; Wolff et al., 2005). The response to UTP consisted of an initial transient stimulation of ISC that was accompanied by a monotonic increase in [Ca2+]i followed by a slowly developing fall in ISC to a value below control. This resembles that described in other absorptive epithelia and therefore accords with the view that apical P2Y2 receptors allow luminal nucleotides to inhibit Na+ absorption (see e.g. Inglis et al., 1999, 2000; Ramminger et al., 1999; Cuffe et al., 2000; Kunzelmann and Mall, 2003; Lazarowski et al., 2004; Kunzelmann et al., 2005). Initially, ATP also evoked a transient rise in ISC resembling that seen during stimulation with UTP and this response was also accompanied by increased [Ca2+]i. However, this initial transient was followed by a slowly developing and sustained stimulation that was in marked contrast to the inhibitory effect of UTP. This discrepancy shows that the electrometric effects of these nucleotides cannot simply be attributed to P2Y2 receptors as these are equally sensitive to ATP and UTP (see e.g. Nicholas et al., 1996).

The anomalous response to ATP

Cross-desensitization experiments showed that the receptors underlying all components of the response to UTP (i.e. the effects on [Ca2+]i and ISC) were subject to ATP-induced desensitization. However, although the initial components of the response to ATP were similarly abolished by prior exposure to UTP, the sustained increase in ISC persisted in UTP-prestimulated cells, and, under these conditions, this response occurred with no overt change in [Ca2+]i. This implies that this part of the response cannot be attributed to a P2Y receptor as all such receptors couple to PLC/IP3 and thus cause rapid increases in [Ca2+]i (Berridge, 1993; Nicholas et al., 1996). It was therefore interesting that adenosine receptor antagonists selectively inhibited this part of the response to ATP, suggesting that the stimulation may actually be mediated by adenosine receptors.

Four adenosine receptor subtypes (A1, A2A, A2B and A3) have been described (Ralevic and Burnstock, 1998; Fredholm et al., 2001) and mRNA encoding the A1, A2A and A2B receptors, but not the A3 receptor, could be found in H441 cells, a result that accords with studies of other airway epithelial cell types (Lazarowski et al., 1992; Clancy et al., 1999; Fredholm et al., 2001; Huang et al., 2001; Cobb et al., 2002, 2003). However, adenosine receptors are characteristically insensitive to ATP (Ralevic and Burnstock, 1998; Fredholm et al., 2001) and so it was not immediately apparent how their expression could explain the sustained increase in ISC described here. A possible resolution of this contradiction came from the fact that epithelial cells express ectonucleotidases that allow ATP in contact with the cell surface to be rapidly converted to adenosine, and it is now clear that adenosine formed in this way can activate specific receptors and thus contribute to the control of epithelial Cl− secretion (see e.g. Huang et al., 2001; Lazarowski et al., 2004).

This prompted us to explore the effects of ATP-γ-S, a nucleotide that can activate P2Y2 receptors (Nicholas et al., 1996), but which is thought to be resistant to such hydrolysis, suggesting that it would evoke a response resembling that seen during stimulation with UTP. However, although the cells consistently responded to ATP-γ-S, our initial data indicated that this nucleotide induced a sustained stimulation of ISC as effectively as ATP. Interestingly, this response was not observed in a second series of experiments undertaken using a different batch of ATP-γ-S (see Materials and methods), although, even in these studies, sustained inhibition was not seen unless the cells were pretreated with an adenosine receptor antagonist. Although these data support the notion that the response to purine nucleotides includes a component mediated via adenosine receptors, the unexpected difference between different batches of ATP-γ-S was surprising. Subsequent analysis showed that the second batch used actually contained substantial amounts of ADP, and, although ATP-γ-S is not subject to hydrolysis, the contaminant would be rapidly converted to adenosine (see e.g. Huang et al., 2001; Lazarowski et al., 2004). Such contamination of commercially available nucleotides has been noted previously and significantly delayed a proper understanding of P2Y receptor pharmacology (see e.g. Nicholas et al., 1996; Wilson et al., 1998).

Pharmacological basis of the response to adenosine

Apical adenosine caused a slowly developing and sustained increase in ISC similar to that seen during exposure to ATP, and cross-desensitization experiments established that prestimulation with adenosine selectively inhibited the sustained component of the response to ATP. Moreover, prestimulation with ATP reduced, but did not abolish, the response to adenosine, and, taken together, these data make it very likely that the anomalous response to ATP is actually mediated by adenosine. We cannot, however, exclude the possibility that at least part of this response may reflect the presence of adenosine as a contaminant of ATP, but this seems unlikely as basolateral adenosine increased ISC while basolateral ATP did not. This finding implies that ATP hydrolysis occurs only at the apical membrane, a conclusion that accords with previous data (Lazarowski et al., 2004).

Subsequent experiments aimed to establish the pharmacological properties of the receptor population underlying this adenosine-evoked increase in ISC. Our initial attempts to construct cumulative concentration–response curves for adenosine receptor agonists and antagonists, which would have allowed the clearest insight into the pharmacology of the receptors, were unsuccessful. We were therefore forced to adopt an alternative strategy in which each cultured epithelial monolayer was exposed to only a single concentration of a particular drug. Although there was variability in the data obtained in this way, these experiments showed clearly that the response to adenosine was concentration dependent and established that SPA, CGS 21680 and IB-MECA could all mimic this response. Analysis of these data indicated that the rank order of potency for the tested compounds was adenosine ≈SPA>CGS 21680 ≈IB-MECA and, as the latter compounds display relatively high affinities for A1, A2A and A3 receptors, respectively (Ralevic and Burnstock, 1998; Fredholm et al., 2001), the fact that none were more potent than adenosine suggest that these receptors do not make a major contribution to the present response.

By inference, these data thus suggest that the increase in ISC is mediated via A2B receptors, but this was difficult to test directly as there are, at present, no selective agonists for this receptor subtype. We therefore investigated the extent to which adenosine receptor antagonists could reverse the adenosine-evoked increase in ISC. These studies showed that DPCPX, a relatively selective A1 receptor antagonist, had no effect upon the response to a maximally effective concentration of adenosine, providing evidence against a major role for these receptors. On the other hand, ZM 241385 and MRS 1706, which block A2A and A2B receptors, respectively, both inhibited the functional response to adenosine. Although we explored the kinetics of these inhibitory effects, we could not discern any unambiguous difference between the compounds and so these studies suggest that the response is mediated by an unidentified A2 receptor subtype and, as mRNA encoding both A2A and A2B receptors was present, it is entirely possible that both may contribute to the response. It is interesting, however, that DPCPX inhibited the sustained component of the response to ATP, but had no effect upon the response to adenosine. The simplest explanation of this is that DPCPX may be unable to antagonize the response to a maximally effective concentration of adenosine, but can block the responses to lower concentrations produced by local hydrolysis of ATP. However, as A1 receptor mRNA was present, it is also possible that concomitant activation of P2Y2 receptors, which will occur during exposure to ATP, may facilitate signalling via these receptors.

Physiological basis of the response to adenosine

The present responses to adenosine were blocked by amiloride and involved clear increases in the apical Na+ conductance and these findings indicate that activation of A2A/B receptors leads to a stimulation of Na+ transport in H441 cells. Although such receptors have previously been described in airway epithelia, previous data suggest that their physiological role is to control the secretion of anions, and hence liquid, into the luminal fluid and this response is thought to reflect activation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) (Lazarowski et al., 1992; Clancy et al., 1999; Huang et al., 2001; Cobb et al., 2002, 2003). It is therefore relevant that at least one previous study of H441 cells has described high levels of CFTR expression and shown that cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-coupled agonists can increase membrane Cl− conductance (Kulaksiz et al., 2002). However, this finding is at variance with data from several subsequent studies, which have independently shown that H441 cells are absorptive and that activation of cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) causes a rise in GNa (Sayegh et al., 1999; Lazrak and Matalon, 2003; Clunes et al., 2004; Ramminger et al., 2004; Shlyonsky et al., 2005). We can offer no explanation for this discrepancy, although it might be relevant that Kulaksiz et al. (2002) did not actually explore the effects of withdrawing external Na+ and thus failed to quantify the membrane Na+ current, which would almost certainly have contributed to the current records shown in their paper (see Clunes et al., 2004; Shlyonsky et al., 2005). Moreover, our own data show that cAMP-elevating compounds selectively increase the amiloride-sensitive component of the membrane conductance, suggesting that any activation CFTR is minimal (Clunes et al., 2004).

As far as we are aware, the present data thus provide the first description of adenosine-evoked Na+ transport in airway epithelial cells, although A1 receptor antagonists have been reported to cause natriuresis and diuresis in vivo (Wilcox et al., 1999) and adenosine appears to activate an amiloride-sensitive Na+ conductance in human intestinal epithelia (Bouritius and Groot, 1997) and stimulate Na+ transport in a renal cell line (A6). The responses seen in A6 cells appear to reflect an A1 receptor-mediated rise [Ca2+]i (Lang et al., 1985; Hayslett et al., 1995; Macala and Hayslett, 2002), but this is unlikely to explain the response described here as the receptors underlying the present response are, at best, only weakly coupled to [Ca2+]i and as DPCPX had no effect upon the response to adenosine. Moreover, A2B and A2A receptors characteristically signal via cAMP/PKA (Ralevic and Burnstock, 1998; Fredholm et al., 2001) and previous studies of H441 cells have shown that the activation of this signalling pathway can lead to an increase in GNa and a consequent stimulation of Na+ transport (e.g. Morris and Schafer, 2002; Lazrak and Matalon, 2003; Clunes et al., 2004; Ramminger et al., 2004). The present response to adenosine was clearly associated with a rise in GNa. It is now clear that cAMP-coupled agonists exert control over GNa by inactivating a mechanism that normally drives the continual removal of Na channel complexes from the apical membrane (Canessa et al., 1993, 1994; Debonneville et al., 2001; Snyder et al., 2001, 2002, 2004; Wang et al., 2001; Kamynina and Staub, 2002; McDonald et al., 2002; Friedrich et al., 2003). However, we have recently shown that adenosine also activates basolateral K+ channels in H441 cells (Inglis and Wilson, 2006) and, although the molecular basis of this response is unknown, the resultant rise in K+ conductance may contribute to adenosine-evoked Na+ transport by hyperpolarizing the membrane potential and increasing the driving force for Na+ entry (see Gordon and MacKnight, 1991). The adenosine-evoked stimulation of Na+ transport described here is thus a complex process and this complexity may, at least in part, explain why it was so difficult to discern the pharmacological properties of the present responses as it makes a simple relationship between fractional receptor occupancy and the rate of Na+ transport highly unlikely.

H441 epithelial cells are derived from the human distal airways and have been reported to display morphological and functional features of Clara cells, secretory cells found in the distal airways (O'Reilly et al., 1989; Kulaksiz et al., 2002). Electrophysiological studies, on the other hand, have shown that these cells express an absorptive phenotype and they have thus become a widely accepted model of the Na+ absorbing surface epithelium of the human distal airway (Sayegh et al., 1999; Lazrak and Matalon, 2003; Clunes et al., 2004; Ramminger et al., 2004; Shlyonsky et al., 2005; Woollhead et al., 2005). The present data, in common with previous (see e.g. Inglis et al., 1999, 2000; Ramminger et al., 1999; Cuffe et al., 2000; Kunzelmann and Mall, 2003; Kunzelmann et al., 2005), show nucleotides can cause sustained inhibition of this ion transport process by activating P2Y2 receptors. However, ATP is subject to rapid extracellular hydrolysis (Lazarowski et al., 2004) to adenosine and it is now clear that this metabolite is capable of inducing a sustained stimulation of Na+ absorption that could lead to dehydration of the airway surface liquid (see, e.g. Boucher, 2004). The present data thus draws attention to the possibility that adenosine may play a previously unrecognized role in airway fluid homeostasis and makes exploring the effects of adenosine receptor agonists/antagonists upon fluid homeostasis in freshly isolated human distal airway epithelial cells important.

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Wellcome Trust for a Prize Studentship (LAC) and Project Grants (REO, SKI and SMW) which made this study possible. We also thank Eduardo Lazarowski and Catja van Heusden for their help with HPLC analysis.

Abbreviations

- A1, A2 and A3 receptor

types 1, 2 and 3 adenosine receptor

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- ADP

adenosine diphosphate

- AMP

adenosine monophosphate

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular free Ca2+ concentration

- CGS-21680

2-p-(2-carboxyethyl)-phenethylamino-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine

- DPCPX

1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- F340

intensity of Fura-2 fluorescence signal evoked by excitation at 340 nM

- F380

intensity of Fura-2 fluorescence signal evoked by excitation at 380 nM

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- IB-MECA

N6-(3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5-N-methyluronamide

- ISC

short-circuit current

- MRS1706

N-(4-acetylphenyl)-2-[4-(2,3,6,7-tetahydro-2,6-dioxo-1,3-dipropyl-1H-purin-8-yl)phenoxy]-acetamide

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PKA

protein kinase A

- NCS

newborn calf serum

- r.u.

ratio units

- Rt

transepithelial resistance

- RT

reverse transcriptase

- s.e.m.

standard error of the mean

- SPA

N6-(p-sulphophenyl)adenosine

- UTP

uridine triphosphate

- Vt

transepithelial voltage

- ZM 241385

4-(2-[7-amino-2-92-furyl)[1,2,4]triazolo[2,3-a][1.3.5]triazin-5-ylamino]ethyl)phenol

References

- Berridge MJ. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling. Nature. 1993;361:315–325. doi: 10.1038/361315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher RC. New concepts of the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:146–158. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00057003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouritius H, Groot JA. Apical adenosine activates an amiloride-sensitive conductance in human intestinal cell line HT29cl19A. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1997;272:C931–C936. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.3.C931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown HA, Lazarowski ER, Boucher RC, Harden TK. Evidence that UTP and ATP regulate phospholipase C through a common extracellular 5′-nucleotide receptor in human airway epithelial cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1991;40:648–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canessa CM, Horisberger JD, Rossier BC. Epithelial sodium channel related to proteins involved in neurodegeneration. Nature. 1993;361:467–470. doi: 10.1038/361467a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canessa CM, Schild L, Buell G, Thorens B, Gautschi I, Horisberger JD, et al. Amiloride-sensitive epithelial Na+ channel is made of three homologous subunits. Nature. 1994;367:463–466. doi: 10.1038/367463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy JP, Ruiz FE, Sorscher EJ. Adenosine and its nucleotides activate wild-type and R1117H CFTR through an A2B receptor coupled pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1999;276:C361–C369. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.2.C361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clunes MT, Butt AG, Wilson SM. A glucocorticoid-induced Na+ conductance in human airway epithelial cells identified by perforated patch recording. J Physiol (London) 2004;557:809–819. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.061143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb BR, Fan L, Kovacs TE, Sorscher EJ, Clancy JP. Adenosine receptors and phosphodiesterase inhibitors stimulate Cl− secretion in Calu-3 cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29:410–418. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0247OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb BR, Ruiz F, King CM, Fortenberry J, Greer H, Kovacs T, et al. A2 adenosine receptors regulate CFTR through PKA and PLA2. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L12–L25. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2002.282.1.L12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuffe JE, Bielfeld-Ackermann A, Thomas J, Leipziger J, Korbmacher C. ATP stimulates Cl− secretion and reduces amiloride-sensitive Na+ absorption in M-1 mouse cortical collecting duct cells. J Physiol. 2000;524:77–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00077.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debonneville C, Flores SY, Kamynina E, Plant PJ, Tauxe C, Thomas MA, et al. Phosphorylation of Nedd4-2 by Sgk1 regulates epithelial channel surface expression. EMBO J. 2001;20:7052–7059. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, Ijzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Klotz K-N, Linden J. International union of pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:527–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich B, Feng Y, Cohen P, Risler T, Vandewalle A, Bröer S, et al. The serine/threonine kinases SGK2 and SGK3 are potent stimulators of the epithelial Na+ channel α,β,γ-ENaC. Pflügers Arch. 2003;445:693–696. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0993-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon LGM, Macknight A. Application of membrane potential equations to tight epithelia. J Membr Biol. 1991;120:155–163. doi: 10.1007/BF01872398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+-indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;265:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayslett JP, Macala LJ, Smallwood JI, Kalghatgi L, Gasalla-Herraiz J, Isales C. Adenosine stimulation of Na+ transport is mediated by an A1 receptor and a [Ca2+]i-dependent mechanism. Kidney Int. 1995;47:1576–1584. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Lazarowski ER, Tarran R, Milgram SL, Boucher RC, Stutts MJ. Compartmentalised autocrine signalling to cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator at the apical membranes of airway epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:14120–14125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241318498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglis SK, Collett A, Mcalroy HL, Wilson SM, Olver RE. Effect of luminal nucleotides on Cl- secretion and Na+ absorption in distal bronchi. Pflügers Arch. 1999;438:621–627. doi: 10.1007/s004249900096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglis SK, Wilson SM.Basolateral K+ conductance in a human airway epithelial cell line Proceedings of the Physiological Society 2006PC14Manchester meeting, Vol 2, pp

- Inglis SK, Wilson SM, Olver RE. Differential effect of ATP and UTP receptor on ion transport processes in porcine tracheal epithelium. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:367–374. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob R. Agonist-stimulated divalent cation entry into single cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Physiol (London) 1990;421:55–77. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp017933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamynina E, Staub O. Concerted action of ENaC, Nedd4-2, and Sgk-1 in transepithelial Na+ transport. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;283:F377–F387. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00143.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko WH, Law WYK, Wong HY, Wilson SM. The simultaneous measurement of ISC and intracellular free Ca2+ in equine cultured equine sweat gland secretory epithelia. J Membr Biol. 1999;170:205–211. doi: 10.1007/s002329900550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko WH, Wilson SM, Wong PYD. Purine and pyrimidine nucleotide receptors in the apical membranes of equine cultured epithelia. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:150–156. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulaksiz H, Schmid A, Hönscheid M, Ramaswamy A, Cetin Y. Clara cell impact in air side activation of CFTR in small pulmonary airways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:6796–6801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102171199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzelmann K, Bachhuber T, Regeer R, Markovich D, Sun J, Schreiber R. Purinergic inhibition of epithelial Na+ transport via hydrolysis of PIP2. FASEB J. 2005;19:142–143. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2314fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzelmann K, Mall M. Pharmacotherapy of the ion transport defect in cystic fibrosis: role of purinergic receptor agonists and other potential therapeutics. Am J Respir Med. 2003;2:299–309. doi: 10.1007/BF03256658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang MA, Preston AS, Handler JS, Forrest JNJ. Adenosine stimulates sodium transport in kidney A6 epithelia in culture. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1985;249:C330–C336. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1985.249.3.C330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarowski ER, Mason SJ, Clarke L, Harden TK, Boucher RC. Adenosine receptors on human airway epithelia and their relationship to chloride secretion. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;106:774–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14412.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarowski ER, Paradiso AM, Watt WC, Harden TK, Boucher RC. UDP activates a mucosal-restricted receptor on human nasal epithelial cells that is distinct from the P2Y2 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2599–2603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarowski ER, Tarran R, Grubb BR, Van Heusden CA, Okada S, Boucher RC. Nucleotide release provides a mechanism for airway liquid surface homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:36855–36864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405367200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazrak A, Matalon S. cAMP Induced changes in apical membrane potentials of confluent H441 monolayers. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L443–L450. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00412.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leipziger J. Control of epithelial transport via luminal P2 receptors. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F419–F432. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00075.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macala LJ, Hayslett JP. Basolateral and apical adenosine receptors mediate sodium transport in cultured renal (A6) cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;283:F1216–F1225. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00085.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason SJ, Paradiso AM, Boucher RC. Regulation of ion transport and intracellular calcium by extracellular ATP in normal human and cystic fibrosis airway epithelium. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;103:1649–1656. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb09842.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcdonald F, Western AH, Mcneil JD, Thomas BC, Olson DR, Snyder JM. Ubiquitin–protein liages WWP2 binds to and down regulates the epithelial Na+ channel. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;283:F431–F436. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00080.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RG, Schafer JA. cAMP increases density of ENaC subunits in the apical membrane of MDCK cells in direct proportion to amiloride-sensitive Na+ transport. J Gen Physiol. 2002;120:71–85. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20018547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas RA, Watt WC, Lazarowski ER, Qing L, Harden TK. Uridine nucleotide selectivity of three phospholipase C-activating P2 receptors: identification of a UDP-selective, a UTP-selective and an ATP- and UTP-specific receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:224–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'reilly MA, Weaver TE, Pilot-Matias TJ, Sarin VK, Gazdar AF, Whitsett JA. In vitro translation, post translational processing and secretion of pulmonary surfactant protein B precursors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;1011:140–148. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(89)90201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:413–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramminger SJ, Collett A, Baines DL, Murphie H, Mcalroy HL, Olver RE, et al. P2Y2 receptor-mediated inhibition of ion transport in distal lung epithelial cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:293–300. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramminger SJ, Richard K, Inglis SK, Land SC, Olver RE, Wilson SM. A regulated apical Na+ conductance in dexamethasone-treated H441 airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L411–L419. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00407.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayegh R, Auerbach SD, Li X, Loftus RW, Husted RF, Stokes JB, et al. Glucocorticoid induction of epithelial sodium channel expression in lung and renal epithelia occurs via trans-activation of a hormone response element in the 5′-flanking region of the human epithelial sodium channel alpha subunit gene. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12431–12437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shlyonsky V, Goolaerts A, Van Beneden R, Sariban-Sohraby S. Differentiation of epithelial Na+ channel function: an in vitro model. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24181–24187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413823200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder PM. The epithelial Na+ channel: cell surface insertion and retreival in Na+ homeostasis and hypertension. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:258–275. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.2.0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder PM, Olsen DR, Thomas BC. Serum and glucocorticoid regulated kinase modulates Nedd-4-2 mediated inhibition of the epithelial Na+ channel. J Biol Chem. 2001;277:5–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100623200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder PM, Steines JC, Olson DR. Relative contribution of Nedd4 and Nedd4-2 to ENaC regulation in epithelia determined by RNA interference. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:5042–5046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312477200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thastrup O, Cullen PJ, Drobak BK, Hanley MR, Dawson AP. Thapsigargin, a tumour promoter, discharges intracellular calcium stores by specific inhibition of the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2466–2470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Barbary P, Maiyar A, Rozansky DJ, Bhargava A, Leong M, et al. SGK integrates insulin and mineralocorticoid regulation of epithelial sodium transport. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F303–F313. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.2.F303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox CS, Welch WJ, Schteiner GF, Beladinelli L. Natriuretic and diuretic actions of a highly selective adenosine A1 receptor antagonist. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:714–720. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V104714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SM, Law VWY, Pediani JD, Allen EA, Wilson G, Khan Z, et al. Nucleotide-evoked calcium signals and anion secretion in equine cultured epithelia that express apical P2Y2 receptors and pyrimidine nucleotide receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:832–838. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SM, Rakhit S, Murdoch R, Pediani JD, Elder HY, Baines DL, et al. Activation of apical P2U purine receptors permits inhibition of adrenaline-evoked cyclic AMP accumulation in cultured equine sweat gland epithelial cells. J Exp Biol. 1996;199:2153–2160. doi: 10.1242/jeb.199.10.2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff SC, Qi A-D, Harden TK, Nicholas RA. Polarized expression of human P2Y receptors in epithelial cells from kidney, lung and colon. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C624–C632. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00338.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong PYD. Control of anion and fluid secretion by apical P2-purinoceptors in the rat epididymis. Br J Pharmacol. 1988;95:1315–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11770.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woollhead AM, Scott JW, Hardie DG, Baines DL. Phenformin and 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside (AICAR) activation of AMP-activated protein kinase inhibits transepithelial Na+ transport in H441 lung cells. J Physiol (London) 2005;566:781–792. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.088674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yerxa BR, Sabater JR, Davis CW, Stutts MJ, Lang-Furr M, Picher M, et al. Pharmacology of INS37217 [P(1)-(uridine 5′)-P(4)-(2′-deoxycytidine 5′)tetraphosphate, tetrasodium salt] a next-generation P2Y2 receptor agonist for the treatment of cystic fibrosis. J Pharm Exp Ther. 2002;302:871–880. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.035485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]