What does it mean to be a health literate patient? What does it mean to be a culturally competent health care provider? How are these concepts related? All health care providers should ask themselves these important questions, not to arrive at an answer, but rather for the wisdom to be gained by trying. Students planning to enter any health or human services field need to be exposed to the vast array of practices and beliefs that inform health care decision making.

Health literacy is more than simply the ability to read; it is a tapestry of skills combining basic literacy, math skills, and a belief in the basic tenets of the treatment modality. To provide culturally competent patient care, health care providers must try to understand their patients' beliefs and assess their health literacy. This paper describes an assignment designed to expose undergraduate students to the health care barriers that people face when they lack the skills to be health literate.

Many definitions of health literacy exist. This paper and the described assignment use the National Library of Medicine's definition: “The degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” [1]. In an age of rapidly changing technology, increased access to diverse kinds of information, and a complex health care system, health literacy will present a challenge for everyone at some point in their lives. Not only will future health care providers be challenged to treat ethnically and linguistically diverse populations, but also people with varying degrees of literacy and myriad cultural and religious beliefs that influence their attitudes and behaviors toward the health care system.

The recent Institute of Medicine report, Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion, outlines the basic skills that individuals need to participate in health care. Patients must be able to:

promote and protect health and prevent disease

understand, interpret, and analyze health information

apply health information to a variety of life events and situations

navigate the health care system

actively participate in encounters with health care providers

understand and give consent

understand and advocate for rights [2]

These are complex, higher level literacy skills, many of which require mediation even for educated consumers. Additionally, clinicians must learn the ways in which compromised literacy manifests itself. To competently provide care to patients with varying degrees of health literacy, providers must master a related set of skills. In addition to clinical skills, health care providers must be able to assess a patient's literacy and cultural beliefs to provide meaningful information.

The following assignment has been designed for students enrolled in an undergraduate introductory health care informatics course. Because the best efforts to explain the experiences of vulnerable populations are often met with blank stares, the intention of this assignment is to evoke the unique combination of frustration and enlightenment that leads to understanding. The objective of the assignment is to enable students to experience compromised health literacy firsthand. Like a frightening diagnosis, compromised health literacy must be experienced to be understood. By removing a skill that most college students take for granted (reading), informatics students were plunged into a low-literacy world. They emerged frustrated and angry, but empathetic.

The “Introduction to Health Care Informatics” course is a one-credit elective course offered as an interdisciplinary undergraduate class. Typically, the class roster is composed of two-thirds nursing and pre-nursing students (i.e., students who hope to enter the competitive nursing program) and one-third health sciences, social work, and other students. The course description reads: “This class is an introduction to the use of information technology in the delivery of health care services. Topics covered include basic databases, health literacy, current and future trends in information technology, and human computer interaction.” The class periods in which health literacy is discussed fall under the stated goal of discussing human factors at play in the integration of technology into health care. Completion of the assignment described here is worth 15% of the grade.

The course begins with a discussion of databases in general terms, the information they contain, and the ways that information is entered and retrieved. Once students have an understanding of basic database architecture, various kinds of databases are examined, from patient record databases to bibliographic databases. The concept of controlled vocabulary is discussed, and examples, from International Classification of Disease (ICD-9) codes to subject headings, are used. To begin the discussion of health literacy, a class period is used to introduce the concept of an information prescription and the role information can play in changing behavior. Website evaluation is discussed, with emphasis placed on identifying the author or sponsor of a Website, as well as its authority and timeliness. Students compare the content of MedlinePlus with other sites aimed at health care consumers.

The next class period begins with an audio excerpt from The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down [3], a book that eloquently chronicles a Hmong immigrant family's attempt to get health care for their epileptic daughter. Approaches to reaching both non-English speaking and low-literate patients are then discussed, along with strategies used by these groups to get information about their health. In light of the earlier discussion about information prescriptions, the class discusses the challenges of providing primary and supplementary information to patients with whom communication is compromised.

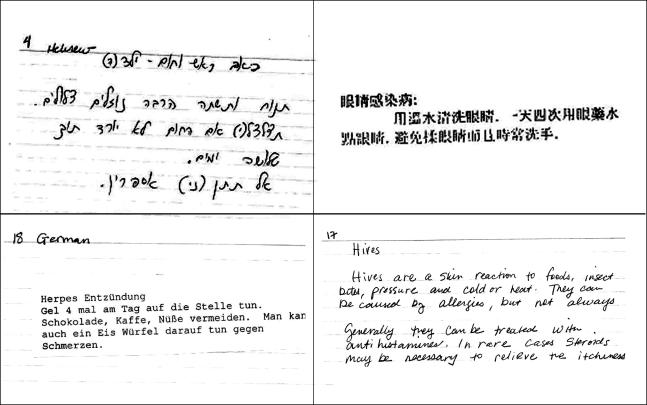

Each student is then given a three-by-five card with an “information prescription” (i.e., a brief description of treatment for a common ailment) on it and told to find additional information on their topic (Figure 1). Students are asked to imagine that this is information a clinician has given them regarding their diagnosis. The information on the cards is written in a variety of languages other than English—including Spanish, Hebrew, French, German, Arabic, Russian—and that language is disclosed. For comparison, a few students receive their prescription in English.

Figure 1.

Examples of information prescriptions distributed in class

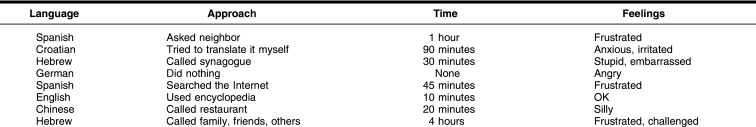

The following week students discuss how they completed the assignment. Discussion includes whom they consulted, what sources they used, how long it took, and whether they were able to locate a translation. Importantly, students are encouraged to discuss how they felt about the assignment. Results are recorded on the whiteboard in class (Table 1). After all students have the chance to share their strategies and feelings with the class, the approaches are evaluated. Building on the earlier discussion of evaluating Websites, it becomes clear that the information gathered from the listed informal sources does not meet most criteria for reliability. Students then understand how compromised literacy can lead to poor health decisions.

Table 1 Students' responses to the assignment

In discussing how they felt about the assignment, some students are hesitant to express anger, although the more time a student spends trying to locate a translation, the likelier they are to broach the subject of frustration. Experience teaching this elective class has shown that undergraduate students' participation varies significantly. Whether a student reports having made a creative attempt, like calling a synagogue or restaurant, seems to correlate to their approach to the class in general. Because this course is an elective, it is difficult to force students to care about one element if they are inclined not to.

Because students' attitudes regarding patients with compromised health literacy have not been pretested and the assignment has only been given to a total of approximately thirty-five students, the results of this assignment are anecdotal. However, students' comments reveal that they experience many of the same things that patients with compromised literacy feel, as well as increased empathy for them. Future research could involve the administration of a pretest and posttest to gather quantitative data measuring students' attitudes toward patients with compromised literacy.

Librarians involved in teaching new skills to their users often begin by attempting to understand the users themselves. By understanding students' (or library users') learning styles, librarians can develop novel ways of connecting them to the information and skills they need. In academia, the use of digital game-based learning to reach students has been discussed [4–6]. Games work as educational tools, proponents argue, because they force the players to remain on the cusp of their competence [7]. Fueled by rewards, players continue to progress through the game's levels while learning new skills. The pedagogy behind this is interpreted by Van Eck to be based on Jean Piaget's model of intellectual development, wherein students ride a cycle of accommodation and assimilation, always learning new information and changing behavior or belief to reflect it. What occurs when new information does not match already held information is described by Piaget as “cognitive disequilibrium” [8]. The approach in this assignment is an extreme example of induced cognitive disequilibrium, akin to pulling the rug out from underneath the students. It is effective in eliciting an emotional reaction when such a reaction might otherwise not occur.

Attempting to alienate or frustrate users is seldom an approach used intentionally by librarians or educators. However, when the goal is to help the student understand how emotions may contribute to a situation—in this case, how anger and frustration may interfere with a patient's health care—experiencing the emotion firsthand can be extremely effective. Without frustration, the full experience of compromised literacy is left to the students' imaginations.

Cultural competence and health literacy are two closely related concepts. Cultural competence is the constant attempt to understand the values, beliefs, traditions, and customs of diverse groups. Culturally competent health care providers are able to appreciate the practices and health beliefs of their patients, without judgment, even when they contradict their own beliefs. Health literacy is the combination of skills that enables people to locate and evaluate health information to make health care decisions for themselves or their families. The practice that is common to both is belief. All individuals choose what information they will believe, and this choice is made within their own cultural milieus. For health care providers to demonstrate cultural competence, they must try to understand what their patients believe and where they get their information, two of the essential elements of health literacy.

Competence is always situational. A nurse who is competent at administering medication may be incompetent at communicating with patients who do not speak English. A brilliant physicist may be an incompetent cook. Communications scholar William Howell proposed five levels of competence in communication: unconscious incompetence, conscious incompetence, conscious competence, unconscious competence, and unconscious supercompetence [9]. Regarding cultural competence, most preclinical undergraduate students are at the lowest level, unconscious incompetence. The goal of this assignment is to guide them to the conscious incompetence level, thereby opening their minds to the concept that cultural competence is a skill that must be cultivated.

Health care providers in the United States today face an increasingly diverse population, as reflected not only in physical and ethnic characteristics, but also in abilities and willingness to participate in care, expectations of health care providers, and definitions of health. Moreover, the available universe of information, from which everyone draws to make decisions, is constantly growing and changing. Any capable health care provider must strive to be culturally competent and aware of health literacy issues to deliver effective health care.

Footnotes

* This paper is based on a poster titled, “Health Literacy: Reaching Students through Unteaching,” presented at MLA '05, the 105th Annual Meeting of the Medical Library Association; San Antonio, TX; May 2005.

REFERENCES

- National Library of Medicine. Current bibliographies in medicine: health literacy. [Web document]. Bethesda, MD: The Library, 2000. [7 Mar 2002; cited 1 Jun 2006]. <http://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/cbm/hliteracy.html>. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Health Literacy, Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health, Institute of Medicine. Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fadiman A. The spirit catches you and you fall down: a Hmong child, her American doctors, and the collision of two cultures. 1st ed. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Oblinger D. Boomers, gen-xers, millennials: understanding new students. EDUCAUSE Rev. 2003 Jul–Aug. 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Prensky M. Engage me or enrage me: what today's learners demand. EDUCAUSE Rev. 2005 Sep–Oct. 61–4. [Google Scholar]

- Foreman J. Game-based learning: how to delight and instruct in the 21st century. EDUCAUSE Rev. 2004 Sep–Oct. 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Gee JP.. Good video games and good learning. Phi Kappa Phi Forum. 2005;85(2:):33–7. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eck R. Digital game-based learning: it's not just the digital natives who are restless. EDUCAUSE Rev. 2006 Mar– Apr. 16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Howell WS. The empathic communicator. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, 1986, c1982. [Google Scholar]