Abstract

Purpose: The paper compares several bedside information tools using user-centered, task-oriented measures to assist those making or supporting purchasing decisions.

Methods: Eighteen potential users were asked to attempt to answer clinical questions using five commercial products (ACP's PIER, DISEASEDEX, FIRSTConsult, InfoRetriever, and UpToDate). Users evaluated each tool for ease-of-use and user satisfaction. The average number of questions answered and user satisfaction were measured for each product.

Results: Results show no significant differences in user perceptions of content quality. However, user interaction measures (such as screen layout) show a significant preference for the UpToDate product. In addition, users found answers to significantly more questions using UpToDate.

Conclusion: When evaluating electronic products designed for use at the point of care, the user interaction aspects of a product become as important as more traditional content-based measures of quality. Actual or potential users of such products are appropriately equipped to identify which products rate the highest on these measures.

Highlights

Users tested products using actual clinical questions, rating content quality similarly among the products but indicating higher ratings for UpToDate in user interaction measures.

Users reported that they found the answers to more questions with UpToDate than the other products evaluated.

Implications for practice

Evaluations need to take into account more than the content of an information product.

User opinions give valuable information on issues such as quality and usability when comparing such products.

Analysis of user preferences may inform design improvements for these resources.

INTRODUCTION

In the past decade, evidence-based medicine (EBM) has become mainstream [1]. EBM can be defined as “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients” [2]. In its original conception, EBM asked practitioners to be able to access the literature when an acute clinical information need arises. This process included four steps. First, formulate a clear clinical question from the patient's problem. Second, search the primary literature for relevant clinical articles. Third, critically appraise the evidence for validity and, finally, implement these findings in practice [3].

One barrier encountered by physicians attempting to answer questions with evidence is lack of time to perform all of the steps outlined above [4]. In an observational study, participating physicians spent less than two minutes seeking the answer to a clinical question [5]. In addition to the lack of time, many clinicians may also lack the skills needed to search, analyze, and synthesize the primary literature [6]. While it could be argued that clinicians could or ought to learn these skills, other professionals already have these skills. In a modern team-based approach to health care, it is natural for others to do the information synthesis and analysis [7]. In the McColl study cited above, 37% of respondents felt the most appropriate way to practice EBM was to use “guidelines or protocols developed by colleagues for use by others.” Only 5% felt that “identifying and appraising the primary literature” was the most appropriate. When others do the searching and synthesizing, clinicians no longer need to assemble the evidence as the need arises. Access to these predigested forms of information readily supports the use of evidence in clinical decision making.

Many electronic products have been specifically designed to provide this sort of synthesized information to the clinician. For the purpose of this discussion, they can be called bedside information tools. Because they have been designed to provide information at the point of care, they tend to provide information that will directly affect patient care. Although like other secondary sources, they can be a good source for background information. What distinguishes these products from sources such as electronic textbooks is this emphasis on point-of-care, patient-oriented information. These products are distinctly different from text-based, point-of-care sources such as printed guidelines: these electronic resources can be updated much more frequently than print resources and provide tools for easily searching and sharing information.

As with other forms of secondary literature, a number of such resources are available from which to choose. With limited financial resources, libraries and other institutions cannot afford to subscribe to or purchase all available bedside information tools. Thus, providing access to all the bedside information tools is not a practical solution. The question then is which bedside information tools should be selected and supported by an institution or library? To make this decision, a method for evaluating these products is needed.

Academic medical and hospital libraries have long been tasked with selecting which information products such as books and journals to purchase and make available to their patrons. This task is often guided by a collection development policy, which states what topics and formats are collected and to what extent. These decisions are driven by the population that the library serves, including people such as researchers, clinicians, and students as well as departments, disciplines, and programs supported by the library. In addition, librarians have traditionally used review tools to aid their decisions. For example, the ISI's Journal Citation Reports contain citation analysis data, including ISI impact factors, often used in decisions about which journals to subscribe to [8]. Another commonly used tool has been the Brandon/Hill selected lists. Compiled by individuals using criteria such as content, authority, scope, audience, and timeliness, the Brandon/Hill selected lists have long been recognized as containing the “best” core books and journals available for medicine, nursing, and allied health. Although the Brandon/Hill selected lists have recently been discontinued [9], their rapid replacement by Doody's Core Titles [10] is testament to how essential librarians have found these tools for collection development.

The evaluation of bedside information tools poses a challenge, as few tools are available to assist the evaluator. Product reviews are sparse. Published reviews were found for each of the five products evaluated in the current work; however, more than one review was found for only four products [11–21]. With frequent updates and changes to electronic information resources, published reviews may quickly become out of date. Often these reviews are only for the personal digital assistant (PDA) version of the product or similarly limited in scope. In addition, published articles about a product are often authored by those involved with the development of the product itself [11, 22–26]. There are no centralized reviewers, as with the Brandon/Hill selected lists, or generally accepted metrics, such as ISI impact factors. While the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society Solution Toolkit [27] is a potential evaluation tool, bedside information tools generally fall outside of its scope; only two of the products evaluated here are included. Without readily available evaluations of these tools, librarians and other decision makers are forced to evaluate these tools themselves [28].

Evaluations of more traditional information products often focus on the product itself, as do many evaluations of information retrieval (IR) systems. The interactive nature of the bedside information products being evaluated requires that a user's interaction with the product be evaluated as well as the content of the product. User-centered evaluations look at the user and the system as a whole when evaluating an IR system [29]. Task-oriented evaluations ask users to attempt a task on the system, then ask if the user is able to complete the task. A task-oriented evaluation of bedside information tools asks the question, “Can users find answers to clinical questions using this tool?,” and seeks to answer the question by having users attempt to complete these tasks. By looking at both the system and the user, these evaluations measure whether or not an IR system does what it is designed to do.

User satisfaction assessment goes one step further and asks not only “Did the system do what it was designed to do?,” but also “Was the user satisfied with the way it did it?” By measuring user satisfaction, an evaluation can identify not only those products that successfully answer clinical questions, but also those products that the users enjoy using the most.

Evaluating and selecting products for others' use can pose a challenge. Evaluators need to be explicit in including potential users of the bedside information resources in these evaluations. Although products must meet minimum standards of quality, by not addressing users in an evaluation, one risks choosing a product that does not suit the users' needs. Therefore, the researchers employed a user-centered, task-oriented approach to evaluate a selection of these bedside information tools. This project aimed to evaluate five bedside information products by measuring the number of questions that can be successfully answered using these products, as well as users' perceptions of both ease of use and the content of the databases.

METHODS

The specific products evaluated in this project were ACP's PIER, DISEASDEX from Thomson Micromedex, FIRSTConsult from Elsevier, InfoRetriever, and UpToDate. These products were selected for practical considerations as they were the ones being considered for purchase or renewal by the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) Library at the time of the study.

User recruitment

After receiving approval from OHSU's Institutional Review Board, participants were recruited via personal contacts, postings on email discussion lists and Websites, and flyers posted on campus. Classes of targeted individuals included physicians, residents, medical students, physician assistants, physician assistant students, nurses, nursing students, pharmacists, and informatics students with current or previous clinical experience. All participants were staff or students at OHSU. When individuals agreed to participate in the study, an investigator met with them personally. At this meeting, the evaluation protocol and background to the study were discussed and the participants were consented. A $20 gift certificate to a local bookstore was offered as an incentive for consented participants to complete the process, but it was not offered initially as an incentive to enroll in the study. Twenty-four participants were consented and accepted into the study; only 18 users completed the process during January and February of 2005.

Trial questions

The test questions used for the evaluations were drawn from a corpus of clinical questions recorded during ethnographic observations of practicing clinicians [30, 31]. To create a set of questions for which these products would be the appropriate resource to find the answers, a number of categories of questions were removed from consideration—patient data questions, population statistic questions, logistical questions, and drug dosing and interaction questions—because these questions would be best answered with other resources such as the patient's chart or drug-specific databases. The remaining questions can be categorized as diagnosis (N = 4), prognosis (N = 3), treatment (N = 4), and guideline (N = 4) questions. This set of fifteen questions was then tested by a group of pilot users, none of whom later participated in the experiment, and some questions were reworded for clarity. The following is a sample of the questions. Appendix A, which appears online, provides the full list of test questions:

What diagnostic tests are recommended for a male with atypical chest pain?

Is it appropriate to use nitroglycerin for episodes of atrial fibrillation?

What are the current guidelines for cholesterol levels?

Experimental design

The experimental design of the allocation of questions, databases, and testers was based on the experimental design specifications set out by the Sixth Text REtrieval Conference (TREC-6) “Interactive Track” [32]. To simulate the clinical setting, users were instructed to spend no more than three minutes on each question, significantly less time than the twenty-minute time limit used in TREC-6 [33]. Each tester was given three unique questions for each database. Following the conventions of TREC-6, no tester saw a question more than once; they approached each system with a fresh set of questions. Over the whole experiment, the questions assigned to each database were randomized so that, although no individual participant attempted the same question on multiple databases, each question was paired with each database at least once. The order in which testers evaluated the systems was also randomized.

Each tester attempted to answer three questions with a specified product, answered a set of user satisfaction questions described further below, and then moved on to the next bedside information tool and set of three questions. Users were asked to complete these evaluations in their own workspace, on their own time. While this did not recreate the use of these products at the bedside, it was a more natural setting than a laboratory and allowed the flexibility needed for recruitment. This evaluation process was tested using the same pilot users mentioned above. Pilot testing indicated that the time commitment for the process was about an hour and that the instructions for logging onto the products and progressing through the evaluations were clear.

Questionnaires

The development of the participant background questionnaire (Appendix B; find online) was guided by the literature. After examining several examples of background questions [34–39], a questionnaire was developed to address likely sources of variation among users: age, gender, profession, years at profession, experience with computers in general, and experience with searching.

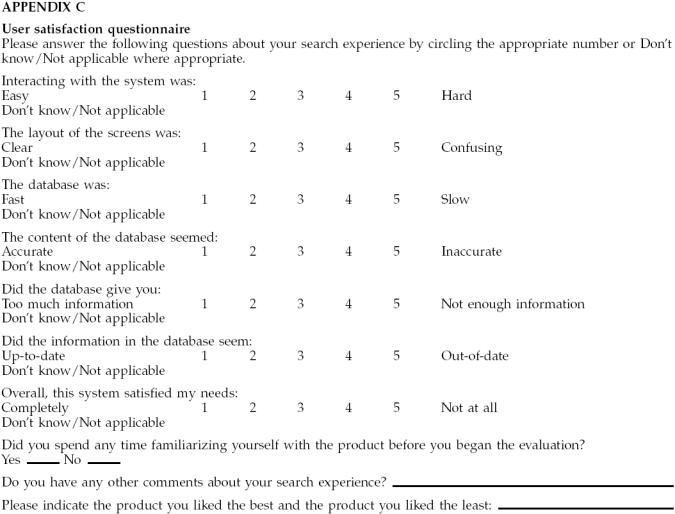

The user satisfaction questionnaire (Appendix C; find online) was also developed from the literature. User evaluation questions were extracted from eleven studies [37–47]. The questions asked by at least two-thirds of the examined questionnaires were transformed into questions that could be answered using a five-point Likert scale. A final opportunity for comments was added at the end, and users were asked to indicate which product they liked the best as well as which product they liked the least.

Statistical analysis

In the user evaluation questions using a Likert-type scale, the questions were phrased such that one was correlated with a desirable trait, such as speed, and five was correlated with an undesirable trait, such as slowness. For the presentation of the results, it was more intuitive for the desirable traits to be associated with higher numbers; thus, the original results were subtracted from six to transform the data before presentation. Responses of “Don't know/Not applicable” were not included in the calculation of the mean scores, resulting in N-values of less than eighteen in some cases. Similarly, some users were only able to identify a product that they liked the best or a product that they liked the least.

The results of the user satisfaction scales are ratings, and the number of answers found were recorded as 0, 1, 2, or 3. Because no assumptions can be made about the distribution or variance of these discrete and ordinal data, the nonparametric Friedman test was used to test the null hypothesis that the mean scores for the products are equal and that the number of questions answered per product were the same. Because best and worst resource rating analysis compares proportions, a chi-squared test was used to compare the percentage of users rating each product the best or the worst.

RESULTS

Participants' backgrounds

The users participating in the study ranged in age from 28 to 49 years (mean age 35 years). The group of users was roughly split between men and women, with 42% men and 58% women. The clinical occupations represented included 8 physicians, 3 pharmacists, 5 medical informatics students with previous clinical experience, 1 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technologist, and a registered nurse. Participants had been at their current profession for 1 to 20 years with a mean of 8 years. All participants were experienced computer users; 94% (N = 17) used a computer more than once a day, with the most common location for computer use being work, and all participants own a computer. While 72% (N = of respondents were familiar with UpToDate, InfoRetriever was only familiar to 2 respondents and only 1 respondent indicated being familiar with either FIRSTConsult, ACP's PIER, or DISEASEDEX.

Average number of answers found

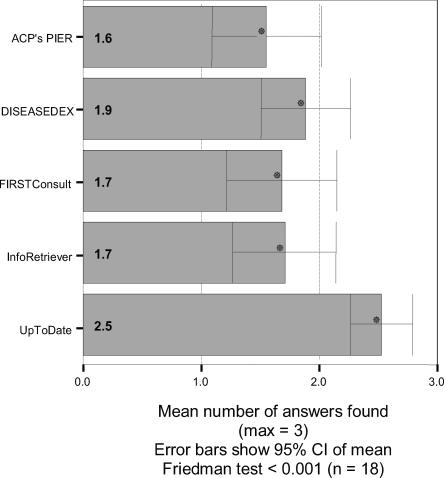

Participants attempted to answer 3 clinical questions using each resource. For each resource, the total number of answers successfully found by each participant was recorded. On average, participants found answers to 2.5 questions in UpToDate, 1.9 questions in DISEASEDEX, 1.7 questions in both FIRSTConsult and InfoRetriever, and 1.6 questions in ACP's PIER. The Friedman test was used to test the null hypothesis that the average number of questions answered was the same for each database. This hypothesis was rejected with a P value of <0.001 (N = 18) (Figure 1), indicating that participants were able to successfully answer more clinical questions with the UpToDate product than with any other resource.

Figure 1.

Average number of answers found

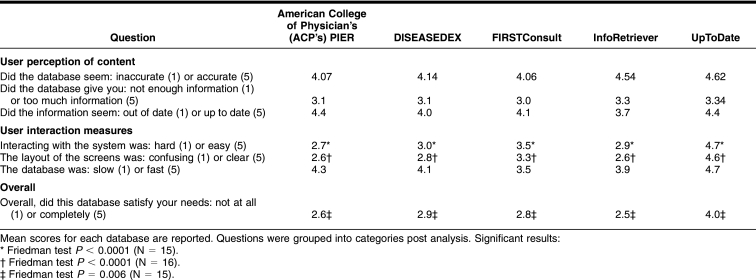

User satisfaction

Results of the user satisfaction survey are reported in Table 1. For questions relating to the user's perception of content (accuracy, amount of information, and timeliness), no significant differences between the products were found. For questions relating to the user experience (interacting with the system, screen layout, and speed), UpToDate was ranked significantly higher (Friedman test P < 0.001) than all other products in all aspects except for speed, where no significant difference was found. In response to the question, “Overall, did this database satisfy your needs?,” UpToDate again ranked significantly higher (Friedman test P = 0.006) than all other products.

Table 1 User satisfaction survey results

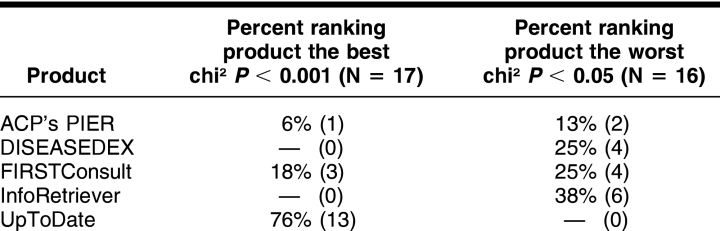

Respondents ranking products best and worst

Thirteen respondents (73%) ranked UpToDate the best, and none ranked it the worst. Six users (38%) rated InfoRetriever the worst, and none found it the best. Four respondents (25%) found DISEASEDEX the worst, and none rated it the best. One individual (6%) found ACP's PIER the best, and two (13%) found it the worst. Three participants (18%) rated FIRSTConsult the best, and four (25%) rated it the worst. A chi-squared analysis found the rankings to be significantly different with a P < 0.05 (Table 2).

Table 2 Respondents rating products best and worst

DISCUSSION

UpToDate ranked high compared to the other products examined by users. Most users ranked UpToDate to be the best product, and none rated it the worst. UpToDate rated the highest on ratings of ease of interaction, screen layout, and overall satisfaction, and users were able to answer significantly more questions with UpToDate than any other product. Any previous experience with products was recorded with the background questionnaire, and very few users were not already familiar with the product. While a user's previous experience might be responsible for its favorable reviews by users, the few that were not familiar with this resource appeared to have similar trends in ranking UpToDate the best and rating the product high on the user satisfaction questionnaire. It is also worth noting that FIRSTConsult was consistently ranked second on a number of scales. This product had never been used at OHSU, and most users were completely unfamiliar with it. If familiarity alone were to account for the favorable reviews of UpToDate, one would not expect FIRSTConsult to garner such favorable reviews as well.

The finding that UpToDate is generally preferred by the users in this study is consistent with studies that tested what tools users select when they have access to more than one tool. These use studies, while not exploring the reasons that people use the products they use, do indicate that when given a choice, users pick UpToDate as a resource very frequently [48, 49].

Unlike some other studies [34, 38, 41], no training on the resources was provided. Users may have had different opinions about some products if they had been trained in their optimal use. However, users were allowed to familiarize themselves with the product before the evaluation if they wished. It can also be argued that sitting down to a resource with no training whatsoever is standard practice; this study attempted to replicate that practice. If a product requires training for users to be successful with it, those training costs must be considered when comparing to other options. An inexpensive product that requires extensive training may be more expensive in the long run than a more expensive product that requires little or no training.

Although thorough efforts were made to recruit a broad sample of potential users, the evaluators were essentially a convenience sample of volunteers. These volunteers might not represent the total user population as they tended to have an interest in these types of products at the study's outset. Their responses may not be typical of other users who, having no interest in the technology, are still “forced” to use these types of products for one reason or other. Another result of relying on pure volunteerism is that the users in various classes were not evenly represented. Input from other types of clinicians, including more nurses, physician's assistants, dentists, and others may have changed the results. Alternately, a more homogenous group could have given more reliable results. The current sample size also precluded comparisons by type of user or previous experience with these products.

From an initial volunteer sample of twenty-four participants, only eighteen completed the study in the time frame of this study. Participants who failed to complete the study did not differ from those who completed the evaluation in terms of recruitment method or clinician type (as ascertained from the initial meeting with these participants). Dropout rates might have been high because participants were asked to perform the evaluations on their own time. A laboratory-based evaluation might have reduced dropout rates but might have also reduced the number of volunteers in total.

In addition to the limitation caused by having a volunteer pool of participants, the products tested also amounted to a convenience sample of those products the OHSU Library was currently interested in. When compared to a different selection of products, UpToDate might not have ranked as high.

Although user evaluations in this study pointed to differences in user interaction scales, those that measured the user's perception of the content of the product (accuracy, currency, and amount of information) did not show any significant differences. Evaluations that focus on the content of an information resource, rather than on the user's experience, would not have revealed the strong user preference for UpToDate. These types of products must be evaluated in terms of user interaction as well as their content. For example, a product selected because of excellent content can be rendered useless by a difficult user interface.

As electronic formats become the expected form for information, as in the case of the products evaluated here, the interface takes on greater significance. In this study, users rated the content of these products to be equivalent but found significant differences in the user interface. In the case of these types of bedside information tools, the interface is the product as much, if not more, than the content of the product. This only underscores that content-focused evaluation methods may no longer be sufficient in evaluating this new breed of information tools.

While users rated the accuracy, amount of information and currency of these products to be roughly equal, they found significant differences in interface features, overall satisfaction, and ability to successfully answer questions. This indicates that more than quality content is necessary for bedside information products to be used to successfully answer clinical questions. Further studies to explore why users had more success with some products than others could lead to a better understanding of the obstacles clinicians face when attempting to answer clinical questions. This understanding could aid in the development of products that are better suited to meet the information needs of clinicians at the point of care.

APPENDIX A

Clinical questions

Is an annual urinalysis adequate to test for diabetic nephropathy in a diabetic?

What is the current thinking on treatment for rheumatoid arthritis?

What are the current guidelines for cholesterol levels?

What diagnostic tests are recommended for a male with atypical chest pain?

How do you treat chondromalacia patellae?

How do you evaluate angina?

How much bleeding is normal in postmenopausal women?

Is it appropriate to use nitroglycerin for episodes of atrial fibrillation?

What is the clinical course for following a child who is knock-kneed (genu valgum)?

Find an overview of renal hypertension.

What is the best approach to treating a woman with a history of abnormal paps?

When is a pelvic ultrasound indicated for a patient having pelvic pain?

What is the appropriate work-up for attention deficit disorder (ADD)?

What are the parameters for hyponatremia?

What is the treatment for gingivitis?

APPENDIX B

Clinical questions

APPENDIX C

User satisfaction questionnaire

Footnotes

* This work was supported by National Library of Medicine Training Grant ASMMI0031 and a Northwest Health Foundation Student Research Grant.

† Based on Campbell R, Ash JS. Comparing bedside information tools: a user-centered, task oriented approach. AMIA Proceedings 2005:101–5.

‡ This article reflects the author's personal view and in no way represents the view of the Department of Veterans Affairs of the US government.

Supplemental electronic content is included with this paper on PubMed Central.

Contributor Information

Rose Campbell, Email: rose.campbell@va.gov.

Joan Ash, Email: ash@ohsu.edu.

REFERENCES

- Guyatt G, Cook D, and Haynes RB. Evidence based medicine has come a long way: the second decade will be as exciting as the first. BMJ. Oct 30; 329(7473:):990–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JAM, Haynes RB, and Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ. 1996 Jan 13; 312(7023:):71–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg W, Donald A. Evidence based medicine: an approach to clinical problem-solving. BMJ. 1995 Apr 29; 310(6987:):1122–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely JW, Osheroff JA, Ebell MH, Chambliss ML, Vinson DC, Stevermer JJ, and Pifer EA. Obstacles to answering doctors' questions about patient care with evidence: qualitative study. BMJ. 2002 Mar 23; 324(7339:):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely JW, Osheroff JA, Ebell MH, Bergus G, Levy BT, Chambliss ML, and Evan ER. Analysis of questions asked by family doctors regarding patient care. BMJ. 1999 Aug 7; 319(7206:):358–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McColl A, Smith H, White P, and Field J. General practitioners' perceptions of the route to evidence based medicine: a questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1998 Jan 31; 316(7128:):361–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer BS, Seymour A, and Capitani C. Bringing the best of medical librarianship to the patient team. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002 Jan; 90(1:):22–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black S. An assessment of social sciences coverage by four prominent full-text online aggregated journal packages. Libr Coll Acq Tech Serv. 1999 Winter; 23(4:):411–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mount Sinai School of Medicine Web Development Team. Brandon/Hill selected lists: overview: important announcement. [Web document]. New York, NY: The School, 2006. [rev. 2006; cited 23 Apr 2006]. <http://www.mssm.edu/library/brandon-hill/index.shtml>. [Google Scholar]

- Doody Enterprises. Doody Enterprises to publish core titles list. [Web document]. Chicago, IL: Doody Enterprises, 2004. [rev. 1 Jun 2004; cited 23 Apr 2006]. <http://www.doodyenterprises.com/news06012004.htm>. [Google Scholar]

- Badgett RG, Murlow CD. Welcome, PIER, a new physicians' information and education resource. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Apr 2; 136(7:):553–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ML. DISEASEDEX general medicine system [review]. J Med Libr Assoc. 2004 Apr; 92(2:):281–2. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick RB.. InfoRetriever basics: a resource for evidence-based clinical information. J Elec Res Med Libr. 2004;1(1:):103–11. [Google Scholar]

- Fox GN, Moawad NS. UpToDate: a comprehensive clinical database. J Fam Pract. 2003 Sep; 52(9:):706–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox GN, Moawad NS, and Music RE. FIRSTConsult: a useful point-of-care clinical reference. J Fam Pract. 2004 Jun; 53(6:):466–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison JA. UpToDate [review]. J Med Libr Assoc. 2003 Jan; 91(1:):97. [Google Scholar]

- Howse D. InfoRetriever 3.2 for Pocket PC [review]. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002 Jan; 90(1:):121–2. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy J. InfoRetriever 2004 [review]. J Med Libr Assoc. 2004 Jul; 92(3:):381–2. [Google Scholar]

- Simonson MT.. Product review: UpToDate. Natl Netw. 2000;24(2:):16–7. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MV, Ellis PS, and Kessler D. FIRSTConsult [review]. J Med Libr Assoc. 2004 Apr; 92(2:):285–7. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasulo P. PIER—evidence-based medicine from ACP. Med Ref Serv Q. 2004 Fall; 23(3:):39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alper BS. Practical evidence-based Internet resources. Fam Pract Manag. 2003 Jul–Aug; 10(7:):49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alper BS, Stevermer JJ, and White DS. Answering family physicians' clinical questions using electronic medical databases. J Fam Pract. 2001 Nov; 50(11:):960–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebell MH, Barry H. InfoRetriever: rapid access to evidence-based information on a hand-held computer. MD Comput. 1998 Sep–Oct; 15(5:):289–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebell MH, Messimer SR, and Barry H. Putting computer-based evidence in the hands of clinicians. JAMA. 1999 Apr 7; 281(13:):1171–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebell HM, Slawson D, Schaugnessy A, and Barry H. Update on InfoRetriever software [letter to the editor]. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002 Jul; 90(3:):343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society. (HIMSS). HIMSS Solution toolkit. [Web document]. Chicago, IL: The Society, 2005. [rev. 2005; cited 23 Nov 2005]. <http://www.solutions-toolkit.com>. [Google Scholar]

- Chueh H, Barnett GO. “Just-in-time” clinical information. Acad Med. 1997 Jun; 72(6:):512–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh WR, Hickam DH. How well do physicians use electronic information retrieval systems? a framework for investigation and systematic review. JAMA. 1998 Oct 21; 280(15:):1347–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman PN. Information needs of physicians. J Am Soc Inf Sci. 1995 Oct; 46(10:):729–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman PN, Helfand M. Information seeking in primary care: how physicians choose which clinical questions to pursue and which to leave unanswered. Med Dec Making. 1995 Apr-Jun; 15(2:):113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Over P. TREC-6 interactive report. In: Voorhees EM, Harman DK, eds. The Sixth Text REtrieval Conference (TREC-6). Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology, 1998:73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Belkin NJ, Carballo JP, Cool C, Lin S, Park SY, Rieh SY, Savage P, Sikora C, Xie H, and Allan J. Rutgers' TREC-6 interactive track experience. In: Voorhees EM, Harman DK, eds. The Sixth Text REtrieval Conference (TREC-6). Gaithersburg, MD: National Institute of Standards and Technology, 1998:597–610. [Google Scholar]

- Hersh WR, Crabtree MK, Hickam DH, Sacharek L, Friedman CP, Tidmarsh P, Mosbaek C, and Kraemer D. Factors associated with success in searching MEDLINE and applying evidence to answer clinical questions. JAMIA. 2002 May– Jun; 9(3:):283–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushniruk AW, Patel C, Patel ML, and Cimino JJ. “Televaluation” of clinical information systems: an integrative approach to assessing Web-based systems. Int J Med Inform. 2001 Apr; 61(1:):45–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh GE, Tan JKH. Computerized databases for emergency care: what impact on patient care? Meth Inf Med. 1994 Dec; 33(5:):507–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su LT.. A Comprehensive and systematic model of user evaluation of Web search engines: I. theory and background. J Am Soc Inf Sci. 2003;54(13:):1175–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hersh W, Crabtree MK, Hickam D, Sacharek L, Rose L, and Friedman CP. Factors associated with successful answering of clinical questions using and information retrieval system. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000 Oct; 88(4:):323–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cork RD, Detmer WM, and Friedman CP. Development and initial validation of an instrument to measure physicians' use of, knowledge about and attitudes toward computers. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1998 Mar–Apr; 5(2:):164–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JA, Brennan Pf, and Patrick TB. Design and evaluation of SchoolhealthLink, a Web-based health information resource. J Sch Nurs. 2003 Dec; 19(6:):351–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupferberg N, Hartel LJ. Evaluation of five full-text drug databases by pharmacy students, faculty, and librarians: do the groups agree? J Med Libr Assoc. 2004 Jan; 92(1:):66–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W.. A database selection expert system based on reference librarian's database selection strategy: a usability and empirical evaluation. J Am Soc Inf Sci. 2002;53(7:):567–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gadd CS, Baskaran P, and Lobach DF. Identification of design features to enhance utilization and acceptance of systems for Internet-based decision support at the point of care. AMIA Proceedings 1998:91–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. Development of a self-assessment method for patients to evaluate health information on the Internet. AMIA Proceedings 1999:540–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll WJ, Torkzadeh G. The measurement of end-user computing satisfaction. MISQ 1988 Jun;259–73. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JR.. IBM computer usability satisfaction questionnaires: psychometric evaluation and instructions for use. Int J Hum Comput Interact. 1995;7(1:):57–8. [Google Scholar]

- Abate MA, Shumway JM, and Jacknowitz AI. Use of two online services as drug information sources for health professionals. Meth Inf Med. 1992 Jun; 31(2:):153–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling LM, Steiner JF, Lundahl K, and Anderson RJ. Residents' patient-specific clinical questions: opportunities for evidence-based learning. Acad Med. 2005 Jan; 80(1:):51–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huan G, Sauds D, and Loo T. Housestaff use of medical references in ambulatory care. AMIA Proceedings 2003:869. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]