Summary

Purification of HA-tagged P2Y2 receptors from transfected human 1321N1 astrocytoma cells yielded a protein with a molecular size determined by SDS-PAGE to be in the range of 57–76 kDa, which is typical of membrane glycoproteins with heterogeneous complex glycosylation. The protein phosphatase inhibitor, okadaic acid, attenuated the recovery of receptor activity from the agonist-induced desensitized state, suggesting a role for P2Y2 receptor phosphorylation in desensitization. Isolation of HA-tagged P2Y2 nucleotide receptors from metabolically [32P]-labeled cells indicated a 3.8 ± 0.2-fold increase in the [32P]-content of the receptor after 15 min of treatment with 100 μM UTP, as compared to immunoprecipitated receptors from untreated control cells. Receptor sequestration studies indicated that ~40% of the surface receptors were internalized after a 15 min stimulation with 100 μM UTP. Point mutation of three potential GRK and PKC phosphorylation sites in the third intracellular loop and C-terminal tail of the P2Y2 receptor (namely, S243A, T344A, and S356A) extinguished agonist-induced receptor phosphorylation, caused a marked reduction in the efficacy of UTP to desensitize P2Y2 receptor signaling to intracellular calcium mobilization, and impaired agonist-induced receptor internalization. Activation of PKC isoforms with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate that caused heterologous receptor desensitization did not increase the level of P2Y2 receptor phosphorylation. Our results indicate a role for receptor phosphorylation by phorbol-insensitive protein kinases in agonist-induced desensitization of the P2Y2 nucleotide receptor.

Abbreviations: AAA-P2Y2, S243A, T344A, and S356A triple mutant of P2Y2; BSA, bovine serum albumin; [Ca2+]i, intracellular free calcium ion concentration; DMEM, Dulbecco’s modified Eagles Medium; EC50, agonist concentration that produces 50% of a response; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; GRK, G protein-coupled receptor kinase; HA, hemagglutinin; Hepes, N-[2-Hydroxyethyl]piperazine-N’-[2-ethanesulfonic acid]; IC50, agonist concentration that inhibits 50% of the response; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; PKC, protein kinase C; PLC-b, phospholipase C-beta; P2Y2-1321N1, HA-tagged P2Y2 transfected 1321N1 cells; PMA, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate; PMSF, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; SEM, standard error of the mean; WT-P2Y2, wild type P2Y2

Introduction

The heptahelical P2Y2 nucleotide receptor couples to the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK), the mobilization of intracellular stores of calcium, the activation of phospholipase C-β(PLC-β), protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms, focal adhesion kinase, and c-Src kinase, and has been implicated in a number of physiological and pathological processes including inflammation (1, 2), reactive astrogliosis (3), and neuroprotection (4). Nucleotides acting through the P2Y2 receptor have been shown to induce Cl− secretion in airway epithelial cells that is not dependent on the cystic fibrosis transmembrane-conductance regulator (5), and P2Y2 receptor ligands have been proposed as novel class of medication for treatment of retinal detachment (6) and improved mucociliary clearance in clinical conditions such as cystic fibrosis (7).

There is limited information regarding the regulation of signaling by the P2Y2 nucleotide receptor. Like in other G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), the P2Y2 nucleotide receptor signaling is regulated by agonist-induced desensitization (8, 9). The mechanisms of GPCR desensitization have been studied most extensively with the b2-adrenergic receptor (10, 11). G protein-coupled receptor kinase (GRK)-mediated phosphorylation increases the binding of cytosolic proteins termed arrestins to the β2-adrenergic receptor, leading to its internalization (12–16). It has been shown that GRK-mediated phosphorylation targets the arrestin-bound b2-adrenergic receptor towards sequestration via clathrin-coated pits (17). Truncation of GPCR C-terminal regions containing consensus sequences for potential phosphorylation by GRKs has been shown to impair β2-adrenergic receptor sequestration (14).

The P2Y2 nucleotide receptor is a Gq protein-coupled receptor that is stimulated equipotently by UTP and ATP, mediating activation of phospholipase C-beta (PLC-β) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (18, 19). We have previously reported that the P2Y2 receptor undergoes rapid agonist-induced desensitization (8, 9, 20). Significantly, treatment of desensitized cells with the protein phosphatase inhibitor, okadaic acid, inhibited resensitization of the receptor, suggesting a role for protein phosphorylation in the regulation of P2Y2 receptor signaling (9, 20). Moreover, truncation mutants indicated an important role for the C-terminal tail of the P2Y2 receptor in desensitization and sequestration of the receptor (8).

In this paper, we have investigated the UTP-induced desensitization, phosphorylation and sequestration of a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope-tagged P2Y2 receptor transfected in 1321N1 human astrocytoma cells. Antibodies directed towards the HA-tag facilitated detection of the P2Y2 receptor by flow cytometry, confocal microscopy, immunoprecipitation, and Western blot in sequestration and phosphorylation assays. Agonist-mediated desensitization of the P2Y2 receptor mediated Ca2+ mobilization correlated with an increase in receptor phosphorylation and sequestration. We confirmed that inhibition of protein phosphatases with okadaic acid decreased receptor resensitization. Furthermore, point mutation of potential sites for GRK and PKC phosphorylation diminished agonist-induced phosphorylation and internalization of the P2Y2 receptor, and the efficacy of UTP to induce desensitization. Interestingly, heterologous desensitization induced by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate occurred in the absence of increased receptor phosphorylation. This study yields a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms for desensitization of the P2Y2 nucleotide receptor.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

[32P]-orthophosphate (HCl-free, carrier-free) and Protein A-Sepharose CL-4B were purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech. Anti-HA 12CA5 and Anti-HA-peroxidase 3F10 monoclonal antibodies were provided by Roche Molecular Biochemicals. Horse radish peroxidase-protein markers for Western blots were purchased from New England Biolabs. Phosphate-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagles Medium (DMEM) and Geneticin were supplied by Invitrogen Life Technologies. Tissue culture reagents were from Hyclone. All other reagents were obtained from Sigma.

P2Y2 receptor gene cDNA construct

The P2Y2 receptor cDNA was subcloned into the retroviral vector pLXSN at the EcoRI /BamHI sites of the multiple cloning site. The open reading frame of the P2Y2 receptor cDNA was modified using polymerase chain reaction to include the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope (YPYDVPDYA) from influenza virus at the amino terminus of the expressed protein, as described previously (8). The forward and reverse HA primers designed for this study were (HA-tag encoded by underlined sequence): 5’–gatcgtgaattctgatgtatccatatgatgttccagattatgctgcagcagacctggaaccctgg–3’ and 5’–gatcgtggatcccctgactgaggtgctatagccg–3’, respectively. A mutant P2Y2 receptor was constructed by changing serine-243, threonine-344, and serine-356 to alanine (AAA-P2Y2). Recombinant cDNA constructs were sequenced on both strands to ensure that mutagenesis had occurred as expected using an ABI Prism automated sequencing apparatus (Perkin-Elmer) and fluorescence dideoxynucleotide technology.

Cell culture and transfection

1321N1 astrocytoma cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% Fetalclone III bovine serum, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 pg/mL streptomycin, 5 mM Hepes and 500 pg/mL Geneticin (G418) (21). Cells were seeded at 2.5 x 106 per 75cm2 tissue culture flasks and grown to ~90% confluency in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. The 1321N1 cells were transfected with HA-tagged P2Y2 receptor cDNA using the pLXSN retroviral vector as described previously (22).

Intracellular free calcium ion mobilization

Activation of the P2Y2 receptor was monitored by detecting changes in intracellular free calcium ion concentration (i.e., [Ca2+]i) in fura2 labeled 1321N1 cells using a dual-excitation spectrofluorimeter, as described previously (9, 23). Cells were assayed in 15 mM Hepes-buffered saline (pH 7.4) containing 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 0.18% (w/v) glucose. Desensitization experiments were performed by incubating the transfected 1321N1 cell suspension with varying concentrations of UTP or PMA for 15 min at 37°C. The cells were pelleted in a microcentrifuge and resuspended in 2 mL Hepes buffer. A concentration of UTP equal to the EC50 value for each cell line was used to rechallenge the cells in receptor desensitization experiments. Calcium mobilization is reported as a ratio relative to the maximal response. Concentration-response data was analyzed with the Prism curve-fitting program (GraphPAD Software for Science, San Diego, CA).

Receptor immunoprecipitation

1321N1 cells were seeded at 2.5 x 106 cells / 25 mL in 25mm x 150mm tissue culture dishes and allowed to grow to ~90% confluency. On the day of the experiment, each cell monolayer was washed two times with 5 mL of serum-free DMEM, leaving 5 mL of the medium over the cells. Then, the cells were either stimulated for 15 min with 100 μM UTP or control-treated with serum-free medium. The culture dishes were placed on ice and the medium was aspirated followed by two washes with ice-cold PBS. The final wash was aspirated and 700 pL of RIPA Buffer (2x) [300 mM NaCl; 100 mM Tris-HCL; 10 mM EDTA; 2% (v/v) NP-40; 1% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate; 0.2% (w/v) SDS; 20 mM NaF; 20 mM disodium pyrophosphate; 20 pg/mL of benzamidine, leupeptin, and soybean trypsin inhibitor; 10 pg/mL aprotinin; 2 pg/mL pepstatin A; and 0.2 mM PMSF; pH 8] was added. The cells were scraped in this volume and solubilized for 1 h at 4°C with gentle rocking. After solubilization, the extract was centrifuged at 200,000 x g for 45 min at 4°C. The supernatant was mixed with 100 mL 10% (w/v) Protein A-Sepharose prepared in 3% BSA/RIPA (1x) buffer and incubated for 1 h at 4°C with gentle rocking. The suspension was centrifuged at 12,000 x g for 2 min at 4°C and the precleared supernatant was mixed with 50 pg anti-HA antibody and 100 pL 10% Protein A-Sepharose. The samples were incubated overnight at 4°C with gentle rocking. On the next day, the gel matrix was washed three times using RIPA (1x) buffer at 4°C and the final pellet was resuspended in 50 pL SDS Loading Buffer (1x). The samples were incubated at 65°C for 10 min to elute the antigen-antibody complexes and the gel matrix was pelleted as before. The supernatant was removed and saved at –20°C until SDS-PAGE (10%) analysis was performed.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot

The immunoprecipitated samples were analyzed in a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred electrophoretically to nitrocellulose membranes using trisglycine transfer buffer and 15V constant voltage in a Semi-dry Transfer System (Bio-Rad) for 1.5 h. The nitrocellulose membrane was blocked for 1 h with 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS-0.1% Tween 20 pH 7.2 (PBS-T), followed by three quick rinses with PBS-T. The membrane was then incubated with 1 pg of anti-HA-peroxidase 3F10 antibody (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) in 10 mL of 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS-T pH 7.2 for 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C with gentle agitation. Anti-biotin-peroxidase (10 mL, New England BioLabs) was also added in order to detect the biotinylated protein standards. The membrane was washed three times for 10 min with PBS-T before adding the luminol detection solution (SuperSignal West Dura, Pierce). The drained nitrocellulose membrane covered with plastic wrap was exposed for 15 min to the Molecular Imager Screen-CH (GS-525 Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) for chemiluminescence analysis of total protein.

Receptor phosphorylation

HA-tagged P2Y2 transfected 1321N1 cells (P2Y2-1321N1) were seeded and grown as mentioned in the receptor immunoprecipitation assay. On the day of the experiment, each cell monolayer was washed two times with 5 mL of phosphate-free, serum-free DMEM, leaving 5 mL of the medium over the cells. Then, 2.5 mCi of [32P]-orthophosphate was added to each dish and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Okadaic acid (1 μM final concentration) was added 10 min prior to the UTP or PMA which was incubated for the final 15 min of the 2 h labeling period according to Freedman et al (24). The P2Y2 receptor was immunopurified and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot as described earlier. Phosphorylation data was acquired prior to chemiluminescence analysis by exposing the nitrocellulose membrane to the Molecular Imager Phosphor Screen-BI™ (GS-525 Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) for 18 h. Total protein was determined via chemiluminescence by exposing the same membrane to the Molecular Imager Screen-CH for 15 min after visualization of bands with anti-HA peroxidase-coupled antibodies as described earlier. Phosphorylation data was normalized to total protein data by dividing [32P] counts by chemiluminescence counts.

Flow cytometry sequestration assay

The procedure was performed essentially as described previously (8). Briefly, P2Y2-1321N1 cells were grown to ~90% confluency in 35-mm2 culture dishes and incubated with 100 μM UTP for various time periods. Control cells were incubated without UTP to allow an estimation of the total detectable cell-surface P2Y2 receptors. UTP-treated cells were then washed with ice-cold Hepes buffer and incubated at 4°C for 1 h with the same buffer containing 10 pg of anti-HA 12CA5 antibody. The cells were washed and incubated with PBS containing 30 pg/mL of Fc-specific fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled goat anti-mouse antibody (Sigma) in the dark at 4°C for 1 h. Control cells were incubated with primary or secondary antibody alone to detect any nonspecific fluorescence. The PBS-washed P2Y2-1321N1 cells were detached from the dishes using Hepes buffer containing 2 mM EDTA. They were centrifuged and resuspended in 1 mL of 1% (v/v) formaldehyde in PBS and incubated in the dark at 4°C for 10 more minutes. Finally, the cells were centrifuged and resuspended in 0.5 mL PBS, and analyzed on an EPICS 753 flow cytometer (Coulter Corp., Hialeah, FL) with a 5-watt argon laser tuned at 488 nm using 150-milliwatt output.

Confocal microscopy

1321N1 cell transfected with either wild type or AAA mutant P2Y2R were cultured in Laboratory-Tek chamber slides (Nalge Nunc Int., Rochester, NY, USA) for 3 days in culture medium. On the day of the assay, cells were equilibrated in serum-free medium for 1 h at 37°C. Nonspecific protein sites were blocked with 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin in PBS (blocking buffer) for 15 min at 4°C. Cells were then incubated with 10 pg/mL anti-HA mouse monoclonal antibody (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) in blocking buffer for 1 h at 4°C to form receptor/antibody complexes and washed three times with ice-cold PBS. Cells were incubated with or without 10 μM UTP at 37°C for 5, 15, or 30 min. The cells washed three times with ice-cold PBS and fixed with 2% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Plasma membrane staining with Wheat Germ Agglutinin-Texas Red (Molecular Probes) was performed as described by Holloway et al. (25). Images were acquired using a Zeiss (Thornwood, NY, USA) LSM-5 Pascal scanning confocal microscope equipped with an Alpha-Fluar 100×1.45 DIC oil immersion objective. Argon and helium-neon lasers were used for excitation of Alexa Fluor 488 and Texas Red, respectively. Emission from Alexa Fluor 488 and Texas Red was detected using BP 505–530 and LP 560 filters, respectively using multitracking scan mode. P2Y2 receptor sequestration was analyzed by determining colocalization of receptor with the plasma membrane marker Wheat Germ Agglutinin-Texas Red (WGA). The weighted colocalization coefficient of immunostained P2Y2 receptor with Wheat Germ Agglutinin-Texas Red (WCC:P2Y2/WGA) was determined using Zeiss LSM 5 Pascal Software Release 3.2 which calculates the coefficient according to the following equation:

Statistical analysis

One-way multiple Tukey comparison post tests analysis of variance test (ANOVA) and unpaired Student’s t-test were used for comparison of multiple groups and two groups, respectively. A probability <0.05 between control and experimental groups was considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were performed with InStat software Version 3.06 (GraphPad Software Inc. San Diego, CA).

Results

N-terminally hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged recombinant P2Y2 receptors were constructed by polymerase chain reaction and expressed in 1321N1 astrocytoma cells to investigate UTP-mediated receptor desensitization, phosphorylation and sequestration. The HA tag (YPYDVPDYA) is specifically recognized by the commercially-available 12CA5 and 3F10 monoclonal antibodies.

Immunoprecipitation of the P2Y2 receptor reveals non-uniform receptor protein distribution

Solubilized protein extracts of HA-tagged P2Y2 transfected 1321N1 cells (P2Y2-1321N1) were immunoprecipitated with 12CA5 anti-HA monoclonal antibody. Western blots of the immunoprecipitated products revealed heterogeneity of receptor protein ranging in size from 57 to 76 kDa, and a single protein band of 45 kDa (Figure 1, lane 2). Vector-transfected 1321N1 cells yielded no immunoprecipitated products nor did the eluent from washed Sepharose matrix (Figure 1, lanes 3 and 4, respectively). No bands were detected in a sample consisting of 12CA5 anti-HA antibody indicating that the detected bands originated from the P2Y2-1321N1 cells and were not contaminants introduced by the antibody used in the immunoprecipitation protocol (Figure 1, lane 6).

Figure 1. Immunoprecipitation of the HA-tagged P2Y2 receptor.

1321N1 cells stably transfected with HA-tagged P2Y2 receptor or with pLXSN vector without receptor were detergent solubilized and immunoprecipitated with 12CA5 anti-HA monoclonal antibody. Immunoprecipitated products were resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose and immunoblotted using 3F10 anti-HA-peroxidase monoclonal antibody. Samples in the blot are: protein standards (lanes 1 and 5), immunoprecipitation from HA- tagged P2Y2 transfected cells (lane 2), immunoprecipitation from pLXSN vector transfected cells (lane 3), products eluted from the anti-HA crosslinked gel matrix (lane 4), and 12CA5 anti-HA antibody only (used for immunoprecipitation reactions) (lane 6). Results shown are representative of three separate experiments.

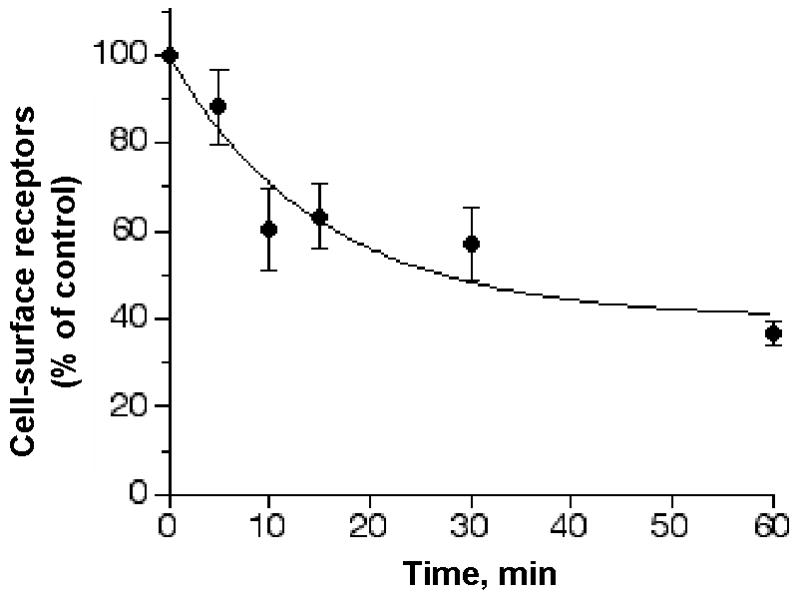

Agonist-mediated P2Y2 receptor desensitization involves phosphorylation

Extracellular UTP caused a concentration-dependent activation of P2Y2 receptors that mediated rapid and transient increases in intracellular free calcium ion concentration ([Ca2+]i) as previously reported (9). The agonist concentration that produces 50% of a response (EC50) value was 0.32 μM (log EC50 = −6.5 ± 0.1) (Table 1). Desensitization of the UTP-mediated calcium response was determined after a 15 min pretreatment of the cells with various UTP concentrations. The desensitization was rapid exhibiting an agonist concentration that inhibits 50% of the response (IC50) value of 6.3 μM (log IC50 = −5.2 ± 0.2) (Table 1). Flow cytometry sequestration analysis of HA-tagged P2Y2 receptors was performed using mouse anti-HA 12CA5 antibody and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled goat anti-mouse antibody. About 40% of the receptors were sequestered within 15 min of incubation with 100 μM UTP (Figure 2).

Table 1.

EC50 and IC50 values for different P2Y2 receptor constructs expressed in 1321N1 cells.

|

EC50, μM (log EC50) |

IC50, μM log (IC50) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| P2Y2Receptor | UTP | UTP | PMA |

| wild type | 0.32 (−6.5±0.1) | 6.3 (−5.2±0.2) | 3.2 (−5.5±0.2) |

| AAA-P2Y2 | 0.20 (−6.7±0.1) | 79 (−4.1±0.2) | 2.0 (−5.7±0.3) |

EC50 (agonist concentration that produces 50% of the maximal response), IC50 (agent concentration that inhibits 50% of a response), log EC50, log IC50 and standard error of the mean (SEM) were determined as described in Experimental Procedures using the Prism 4.0 software, GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA.

Figure 2. UTP-induced sequestration of P2Y2 receptors expressed in 1321N1 cells.

1321N1 cells expressing HA-tagged P2Y2 receptors were incubated at 37°C with 100 μM UTP for the indicated times. Control cells were incubated without UTP to determine the total detectable cell-surface P2Y2 receptors. The cells were washed in assay buffer and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled goat anti-mouse antibody at 4°C in the dark for 1 h. Cells were washed again and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in Experimental Procedures. Each value shown is expressed as a percentage of the total P2Y2 receptors detected in control cells that were treated with UTP-free carrier buffer. The data presented are the average ± SEM of results from three independent experiments.

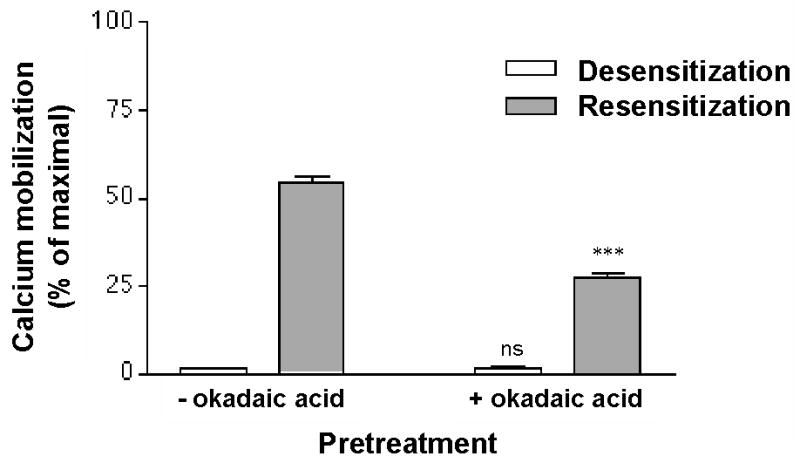

Previous reports have suggested that receptor phosphorylation plays a role in the modulation of P2Y2 receptor desensitization and recovery (9, 20). Consistent with this idea, we observed that recovery of P2Y2 receptor signaling after agonist-induced desensitization was inhibited in 50% upon treatment with 1 μM of the protein phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid (Figure 3). Okadaic acid treatment had no effect on receptor desensitization. However, to directly assess phosphorylation of the P2Y2 receptor, we developed a receptor phosphorylation assay using an immunopurification protocol to examine metabolically [32P]-orthophosphate labeled P2Y2-1321N1 cells. Treatment of [32P]-orthophosphate labeled cells with 100 μM UTP agonist caused a significant increase in the [32P]-radioactivity associated with immunoprecipitated proteins in the 57–76 kDa region as compared to control unstimulated cells (Figure 4A).

Figure 3. Effect of the phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid on recovery of P2Y2 receptor from UTP-induced desensitization.

Fura2 labeled P2Y2-1321N1 cells were incubated with 100 μM UTP for 15 min at 37°C in the presence of 1 μM okadaic acid. The cells were washed, resuspended in buffer and either assayed immediately for Ca2+ mobilization (open bars), or incubated for 30 min in UTP-free medium (shaded bars), in the presence or absence of 1 μM okadaic acid prior to measuring changes in [Ca2+]i in response to 1 μM UTP as described in Experimental Procedures. Data are expressed as a percentage of the maximal response to 100 μM UTP in control untreated cells. Data are the average ± SEM of results from three independent experiments. Cells with okadaic acid treatment were compared to parallel cultures without okadaic acid treatment (*** p<0.001; ns, p>0.05 one-way ANOVA).

Figure 4. UTP-induced phosphorylation of P2Y2 receptors.

1321N1 cells expressing the HA-tagged P2Y2 receptor gene were metabolically labeled with [32P]-orthophosphate for 2 h in serum-free and phosphate-free medium and then challenged with 100 μM UTP for 15 min as described in Experimental Procedures. Control-unstimulated cells were challenged with carrier medium. Cells were lysed and detergent-solubilized cell extracts were analyzed by anti-HA immunoprecipitation, SDS-PAGE (10%), and Western blot. The [32P]-radioactivity data were acquired prior to chemiluminescence analysis by exposing the nitrocellulose membrane to the Molecular Imager Screen-BI for 18 h. Total protein in the membrane was then analyzed after chemiluminescence detection by incubating the same nitrocellulose membrane with peroxidase-conjugated anti-HA antibody followed by luminol substrate incubation and exposure to the Molecular Imager Screen-CHEMI for 15 min. (A) Chemiluminescence (left panel) and [32P]-radioactivity (right panel) signals were detected in the same nitrocellulose membrane. Molecular weight standards are indicated on the left. (B) Chemiluminescence and [32P]-radioactivity counts (arbitrary units) were detected in the nitrocellulose membrane (thick line, UTP-treated cells; thin line, control unstimulated cells) and are expressed as a function of protein migration distance (in mm) from top to bottom of the scanned membrane. [32P]-radioactivity counts from phosphorylated proteins were normalized by calculating the ratio to chemiluminescence counts from total immunoprecipitated protein. UTP treatment caused a 3.8 ± 0.2-fold increase in phosphorylation as compared to control unstimulated cells. Results shown are representative of three separate experiments.

The [32P]-radioactivity data was normalized to the total protein detected by chemiluminescence analysis of the same nitrocellulose membrane using anti-HA-peroxidase antibody and a luminol substrate. Thus, the ratio of [32P]-radioactivity counts to chemiluminescence counts was determined for immunoprecipitated samples from UTP-treated cells and control unstimulated cells (Figure 4B). A 3.8 ± 0.2-fold increase in [32P]-content (phosphorylation) was obtained for the P2Y2 receptor after 15 min of stimulus with UTP.

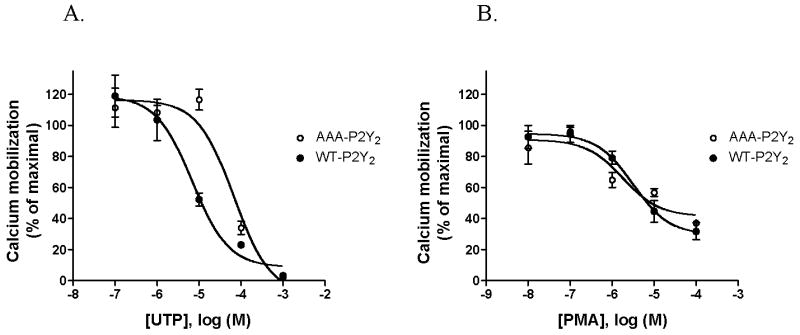

Elimination of potential GRK and PKC phosphorylation sites attenuates agonist-induced but not phorbol ester-induced P2Y2 receptor desensitization and phosphorylation

Examination of the primary structure of the P2Y2 receptor revealed the presence of serine and threonine residues within GRK/PKC consensus substrate sequences (26, 27) in the intracellular domains (28). A mutant HA-tagged P2Y2 receptor was constructed by changing serine-243, threonine-344 and serine-356 to alanine (AAA-P2Y2) to test the hypothesis that phosphorylation of the P2Y2 receptor may be implicated in agonist-induced desensitization. We transfected the AAA-P2Y2 receptor cDNA into 1321N1 cells and tested the receptor’s capacity to signal through calcium mobilization and its desensitization. The AAA-P2Y2 receptor induced the mobilization of intracellular stores of calcium with an EC50 value for UTP of 0.20 μM (log EC50 = −6.7 ± 0.1) (Table 1) which is comparable to that for the wild type P2Y2 receptor (WT-P2Y2). Desensitization of the Ca2+ response was determined in cells expressing either wild type or AAA-P2Y2 receptors. Cells were pretreated for 15 min with various concentrations of UTP, as indicated in Figure 5A, and then rechallenged with a concentration of UTP equal to the corresponding EC50 value for each cell line, i.e., 0.32 μM and 0.20 μM for wild type and AAA-P2Y2 receptors, respectively. Interestingly, the IC50 value for UTP was ~10-fold higher for the AAA-P2Y2 receptor (IC50 = 79 μM, log IC50 = −4.1 ± 0.2) than for the wild type receptor (IC50 = 6.3 μM, log IC50 = −5.2 ± 0.2) (Figure 5A and Table 1). Moreover, when cells were pretreated for 15 min with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), known to activate PKC isoforms and to cause heterologous desensitization of the P2Y2 receptor (8, 9), we found no significant difference between the IC50 values for PMA determined in cells expressing AAA-P2Y2 receptors (IC50 = 2.0 μM, log IC50 = −5.7 ± 0.3) and those expressing wild type P2Y2 receptors (IC50 = 3.2 μM, log IC50 = −5.5 ± 0.2) (Figure 5B and Table 1).

Figure 5. Desensitization of wild type and AAA-P2Y2 receptors mediated by UTP and PMA.

Potential serine/threonine phosphorylation sites for GRK and PKC in the receptor (S243, T344, S356) were mutated to alanine to create the AAA-P2Y2 receptor. 1321N1 cells expressing either wild type (WT,•) or AAA-P2Y2 (○) receptor were labeled with fura2 and incubated for 15 min with various concentrations of either UTP (A) or phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (B). Ca2+ mobilization was determined after rechallenging the cells with the EC50 concentration for UTP of each transfected cell (wild type EC50 = 0.32 μM and AAA-P2Y2 mutant EC50 = 0.20 μM). The data are expressed as a percentage of the maximal response to 100 μM UTP in cells that were not preincubated with UTP or PMA. Values shown are the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments.

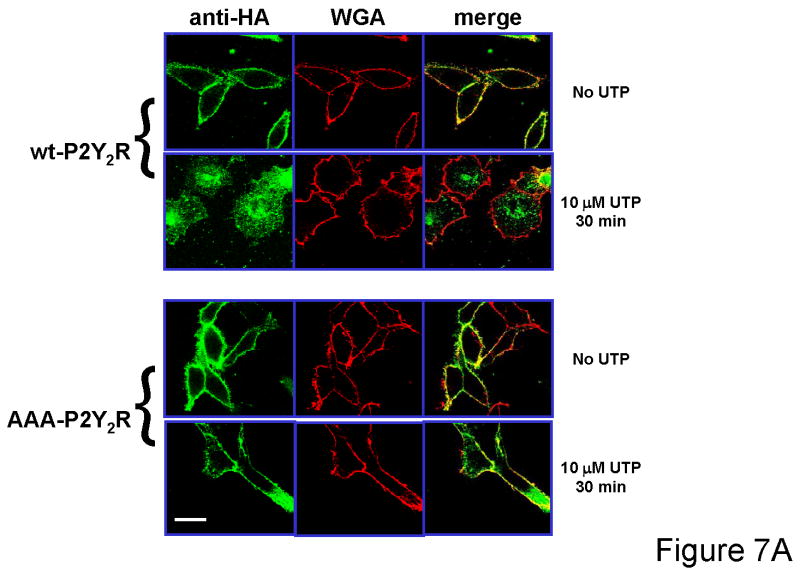

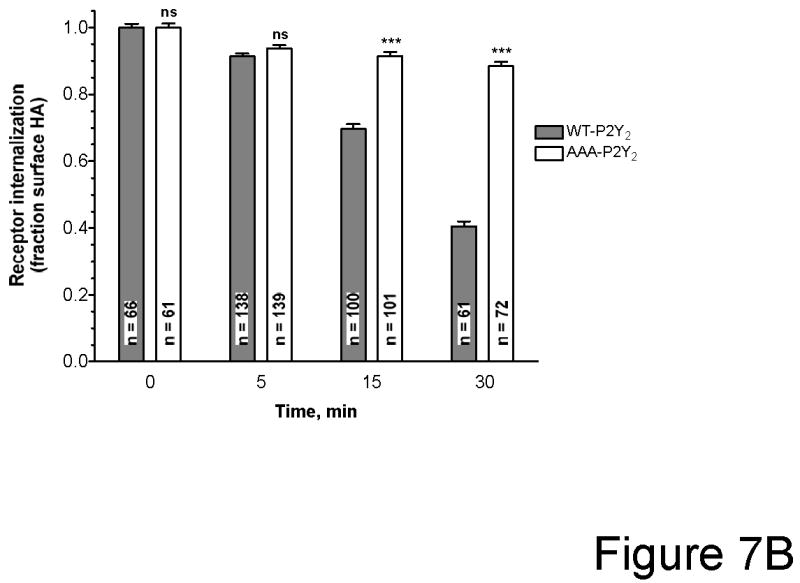

We found that UTP-induced phosphorylation of the AAA-P2Y2 receptor was markedly reduced as compared to the wild type P2Y2 receptor (Figure 6). No increase in receptor phosphorylation was detected upon treatment with 10 μM PMA for 15 min in either wild type or AAA-P2Y2 receptors (Figure 6). Importantly, agonist-induced internalization was significantly impaired in AAA-P2Y2 receptors compared to wild type P2Y2 receptors (Figure 7). Taken together, these results implicate the phosphorylation of potential GRK/PKC phosphorylation sites in agonist-induced desensitizaition of the P2Y2 receptor. Our data also indicate that PMA induces heterologous desensitization of the P2Y2 receptor independent of receptor phosphorylation.

Figure 6. Phosphorylation of wild type and AAA-P2Y2 receptors mediated by UTP and PMA.

1321N1 cells expressing either wild type or AAA-P2Y2 receptor were labeled with [32P]-orthophosphate for two hours in serum-free and phosphate-free medium. Cells were challenged for 15 min with 100 μM UTP or 10 μM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA). Control unstimulated cells were treated with carrier medium. Detergent solubilized cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody followed by SDS-PAGE (10%) and Western blot as described in Methods. [32P]-radioactivity counts from phosphorylated proteins were normalized by calculating the ratio to chemiluminescence counts from total immunoprecipitated protein as described in Figure 6. Results are the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments (**p<0.01, significantly different from unstimulated control).

Figure 7. Internalization of wild type P2Y2 and AAA-P2Y2 receptors transfected in 1321N1 cells.

(A) 1321N1 cells expressing either HA-tagged wild type or AAA-P2Y2 receptors were treated with or without 10 μM UTP for 30 min as described in Experimental Procedures. Laser scanning confocal microscopy images were acquired as described in Experimental Procedures. The HA-tagged receptors were detected by immunoflurescence with Alexa Fluor 488 staining (shown in green) and cell surface N-acetylglucosamine and N-acetylneuraminic acid residues in the same cells were detected with Texas Red-conjugated wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) (shown in red). Merge images are shown. Scale bar in lower left corner = 20 μm. (B) The weighted colocalization coefficient of the HA-tagged P2Y2 receptors with WGA were determined as described in Experimental Procedures. Receptor internalization (fraction surface HA-tagged) was determined at the indicated times after treatment with 10 μM UTP. The surface HA-tagged receptors were calculated from the ratio of WCC values to WCC in unstimulated control cells. Data presented are the average ± SEM of n individual cells (as indicted inside each bar) determined from at least three independent experiments. Cells expressing wild type P2Y2 receptors were compared to cells expressing AAA-P2Y2 receptors (*** p<0.001; ns, p>0.05 one-way ANOVA).

Discussion

The therapeutic potential of nucleotides and P2Y2 receptor ligands may depend on our understanding of the desensitization process that modulates signaling by this receptor. Desensitization of G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) may require the activities of several protein kinases such as protein kinase A (PKA), protein kinase C (PKC) and G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) (29, 30). Although the molecular basis for desensitization of the adenylyl cyclase-linked b2-adrenergic receptor has been well characterized, less is known about the regulatory mechanisms involved in the desensitization of signaling by the P2Y2 nucleotide receptor. Immunoprecipitation of the HA-tagged P2Y2 receptor expressed in 1321N1 astrocytoma cells revealed a non-uniform distribution of the receptor protein that is typical of membrane glycoproteins with heterogeneous complex glycosylation (Figure 1). This most likely results from asparagine-linked high mannose carbohydrates as well as hybrid and complex oligosaccharides since immunoprecipitated P2Y2 receptors were found to be susceptible to hydrolisis by peptide N-glycosidase F (data not shown). A similar heterogeneous pattern was reported for the b2-adrenergic receptor which has a molecular mass of 46,556 and was detected in the 47–90 kDa size range (31).

UTP-mediated activation of the P2Y2 receptor triggers the phospholipase C (PLC) signaling pathway leading to the production of inositol–1,4,5-triphosphate which increases [Ca2+]i, and diacylglycerol which activates PKC. EC50 values for Ca2+ mobilization determined with the HA-tagged P2Y2 receptor transfected cells (0.32 μM; Table 1) were similar to those obtained by us (20) for endogenous P2Y2 receptors in human monocytic U-937 cells (0.44 μM). A 15 min treatment with 100 μM UTP produced rapid desensitization showing an IC50 value of 6.3 μM (Table 1). We confirmed that treatment of desensitized cells with the protein phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid (1 μM) inhibited the recovery of receptor activity from the desensitized state by ~50% (9), suggesting a role for P2Y2 receptor phosphorylation in the desensitization process (Figure 3). These results prompted us to investigate whether UTP-mediated desensitization involved an increase in receptor phosphorylation. Indeed, the P2Y2 receptor was phosphorylated after an agonist treatment that caused desensitization and receptor internalization by 40% (Figures 2 and 4). These results suggest a link between receptor phosphorylation and agonist-induced desensitization. Interestingly, immunoprecipitation of detergent-solubilized total cell extracts from UTP-stimulated cells yielded an unphosphorylated ~45 kDa protein band. Receptors from non-plasmatic membranes (e.g., non-glycosylated receptors in endoplasmic reticulum membranes) would not be accessible to extracellular ligands and thus, remain un-phosphorylated upon agonist challenge

Studies of other GPCRs have indicated the importance of the C-terminus in agonist-mediated receptor regulation, since this portion of the receptor contains potential phosphorylation sites for protein kinases. For example, truncation of the C-terminus of the α1b-adrenergic receptor exhibited decreased agonist-mediated desensitization, phosphorylation and sequestration when compared to wild type receptors (32). C-terminus truncations of other GPCRs such as angiotensin II, neurotensin and the parathyroid hormone receptor, have been observed to inhibit receptor sequestration as well (33–35). Studies from our laboratory have shown that the C-terminus of the P2Y2 receptor is important for both agonist-mediated desensitization and sequestration (8). Therefore, we constructed a mutated AAA-P2Y2 receptor by changing three potential GRK and PKC phosphorylation sites to alanine (S243, T344, S356) located in the C-terminus tail and the third intracellular loop of the P2Y2 receptor. While the triple mutation did not affect the receptor’s ability to activate calcium mobilization, it dramatically reduced the extent of phosphorylation of the receptor upon activation with agonist as well as the efficacy of agonist towards inducing receptor desensitization. It is very likely that agonist-mediated homologous desensitization of P2Y2 receptors involves protein kinases other than PMA-activated PKC isoforms, such as the GRKs; although PMA-insensitive PKC isoforms have not been ruled out. Receptor phosphorylation may modulate its affinity to agonist, its ability to couple with signal transducers, and mediates its internalization by promoting receptor trafficking towards endocytic pathways. It is possible that PKC-mediated heterologous desensitization of the P2Y2 receptor involves phosphorylation of signaling molecules other than the heptahelical receptor, such as phospholipase C (36), regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) (37, 38), and GRK2 (39, 40).

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health through grants S06 GM-08102, P20 RR-15565, P01 AG-018357 and R01 DE-007389, and the University of Missouri-Columbia Food for the 21st Century Program.

References

- 1.Hanley PJ, Musset B, Renigunta V, Limberg SH, Dalpke AH, Sus R, Heeg KM, Preisig-Muller R, Daut J. Extracellular ATP induces oscillations of intracellular Ca2+ and membrane potential and promotes transcription of IL-6 in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9479–9484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400733101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kannan S. Neutrophil chemotaxis: potential role of chemokine receptors in extracellular nucleotide induced Mac-1 expression. Med Hypotheses. 2003;61:577–579. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(03)00234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neary JT, Baker L, Jorgensen SL, Norenberg MD. Extracellular ATP induces stellation and increases glial fibrillary acidic protein content and DNA synthesis in primary astrocyte cultures. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1994;87:8–13. doi: 10.1007/BF00386249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chorna NE, Santiago-Perez LI, Erb L, Seye CI, Neary JT, Sun GY, Weisman GA, Gonzalez FA. P2Y receptors activate neuroprotective mechanisms in astrocytic cells. J Neurochem. 2004;91:119–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stutts MJ, Chinet TC, Mason SJ, Fullton JM, Clarke LL, Boucher RC. Regulation of Cl-channels in normal and cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells by extracellular ATP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:1621–1625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nour M, Quiambao AB, Peterson WM, Al-Ubaidi MR, Naash MI. P2Y(2) receptor agonist INS37217 enhances functional recovery after detachment caused by subretinal injection in normal and rds mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:4505–4514. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kellerman DJ. P2Y(2) receptor agonists: a new class of medication targeted at improved mucociliary clearance. Chest. 2002;121:201S–205S. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.5_suppl.201s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garrad RC, Otero MA, Erb L, Theiss PM, Clarke LL, Gonzalez FA, Turner JT, Weisman GA. Structural basis of agonist-induced desensitization and sequestration of the P2Y2 nucleotide receptor. Consequences of truncation of the C terminus. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29437–29444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Otero M, Garrad RC, Velazquez B, Hernandez-Perez MG, Camden JM, Erb L, Clarke LL, Turner JT, Weisman GA, Gonzalez FA. Mechanisms of agonist-dependent and -independent desensitization of a recombinant P2Y2 nucleotide receptor. Mol Cell Biochem. 2000;205:115–123. doi: 10.1023/a:1007018001735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bouvier M, Hausdorff WP, De Blasi A, O'Dowd BF, Kobilka BK, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Removal of phosphorylation sites from the beta 2-adrenergic receptor delays onset of agonist-promoted desensitization. Nature. 1988;333:370–373. doi: 10.1038/333370a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hausdorff WP, Bouvier M, O'Dowd BF, Irons GP, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Phosphorylation sites on two domains of the beta 2-adrenergic receptor are involved in distinct pathways of receptor desensitization. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:12657–12665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Premont RT, Inglese J, Lefkowitz RJ. Protein kinases that phosphorylate activated G protein-coupled receptors. Faseb J. 1995;9:175–182. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.2.7781920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gurevich VV, Pals-Rylaarsdam R, Benovic JL, Hosey MM, Onorato JJ. Agonist-receptor-arrestin, an alternative ternary complex with high agonist affinity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28849–28852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.28849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferguson SS, Barak LS, Zhang J, Caron MG. G-protein-coupled receptor regulation: role of G-protein-coupled receptor kinases and arrestins. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1996;74:1095–1110. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-74-10-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterne-Marr R, Benovic JL. Regulation of G protein-coupled receptors by receptor kinases and arrestins. Vitam Horm. 1995;51:193–234. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(08)61039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koenig JA, Edwardson JM. Endocytosis and recycling of G protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1997;18:276–287. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zuker CS, Ranganathan R. The path to specificity. Science. 1999;283:650–651. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5402.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erb L, Lustig KD, Sullivan DM, Turner JT, Weisman GA. Functional expression and photoaffinity labeling of a cloned P2U purinergic receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10449–10453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boarder MR, Weisman GA, Turner JT, Wilkinson GF. G protein-coupled P2 purinoceptors: from molecular biology to functional responses. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1995;16:133–139. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)89001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santiago-Perez LI, Flores RV, Santos-Berrios C, Chorna NE, Krugh B, Garrad RC, Erb L, Weisman GA, Gonzalez FA. P2Y(2) nucleotide receptor signaling in human monocytic cells: activation, desensitization and coupling to mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Cell Physiol. 2001;187:196–208. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parr CE, Sullivan DM, Paradiso AM, Lazarowski ER, Burch LH, Olsen JC, Erb L, Weisman GA, Boucher RC, Turner JT. Cloning and expression of a human P2U nucleotide receptor, a target for cystic fibrosis pharmacotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3275–3279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen T, Erb L, Weisman GA, Marchese A, Heng HH, Garrad RC, George SR, Turner JT, O'Dowd BF. Cloning, expression, and chromosomal localization of the human uridine nucleotide receptor gene. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:30845–30848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.30845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freedman NJ, Liggett SB, Drachman DE, Pei G, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Phosphorylation and desensitization of the human beta 1-adrenergic receptor. Involvement of G protein-coupled receptor kinases and cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17953–17961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holloway AC, Qian H, Pipolo L, Ziogas J, Miura S, Karnik S, Southwell BR, Lew MJ, Thomas WG. Side-chain substitutions within angiotensin II reveal different requirements for signaling, internalization, and phosphorylation of type 1A angiotensin receptors. Molecular Pharmacology. 2002;61:768–777. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.4.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seibold A, January BG, Friedman J, Hipkin RW, Clark RB. Desensitization of beta2-adrenergic receptors with mutations of the proposed G protein-coupled receptor kinase phosphorylation sites. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7637–7642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mellor H, Parker PJ. The extended protein kinase C superfamily. Biochem J. 1998;332 (Pt 2):281–292. doi: 10.1042/bj3320281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weisman GA, Gonzalez FA, Erb L, Garrad RC, Turner JT. The cloning and expression of G protein-coupled P2Y nucleotide receptors. In: Fedan JS, editor. The P2 Nucleotide Receptors. Humana Press: Totowa, NJ; 1998. pp. 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turner JT, Weisman GA, Fedan JS. 1998. The P2 Nucleotide Receptors. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lefkowitz RJ. G protein-coupled receptors. III New roles for receptor kinases and beta-arrestins in receptor signaling and desensitization. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18677–18680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Zastrow M, Kobilka BK. Ligand-regulated internalization and recycling of human beta 2-adrenergic receptors between the plasma membrane and endosomes containing transferrin receptors. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:3530–3538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lattion AL, Diviani D, Cotecchia S. Truncation of the receptor carboxyl terminus impairs agonist-dependent phosphorylation and desensitization of the alpha 1B-adrenergic receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22887–22893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang Z, Chen Y, Nissenson RA. The cytoplasmic tail of the G-protein-coupled receptor for parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related protein contains positive and negative signals for endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:151–156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas WG, Thekkumkara TJ, Motel TJ, Baker KM. Stable expression of a truncated AT1A receptor in CHO-K1 cells. The carboxyl-terminal region directs agonist-induced internalization but not receptor signaling or desensitization. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:207–213. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chabry J, Botto JM, Nouel D, Beaudet A, Vincent JP, Mazella J. Thr-422 and Tyr-424 residues in the carboxyl terminus are critical for the internalization of the rat neurotensin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2439–2442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Litosch I. Novel mechanisms for feedback regulation of phospholipase C-beta activity. IUBMB Life. 2002;54:253–260. doi: 10.1080/15216540215673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sato M, Moroi K, Nishiyama M, Zhou J, Usui H, Kasuya Y, Fukuda M, Kohara Y, Komuro I, Kimura S. Characterization of a novel C. elegans RGS protein with a C2 domain: evidence for direct association between C2 domain and Galphaq subunit. Life Sci. 2003;73:917–932. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00355-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cunningham ML, Waldo GL, Hollinger S, Hepler JR, Harden TK. Protein kinase C phosphorylates RGS2 and modulates its capacity for negative regulation of Galpha 11 signaling. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:5438–5444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007699200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krasel C, Dammeier S, Winstel R, Brockmann J, Mischak H, Lohse MJ. Phosphorylation of GRK2 by protein kinase C abolishes its inhibition by calmodulin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1911–1915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lorenz K, Lohse MJ, Quitterer U. Protein kinase C switches the Raf kinase inhibitor from Raf-1 to GRK-2. Nature. 2003;426:574–579. doi: 10.1038/nature02158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]