Abstract

ATP-loaded liposomes (ATP-L) infused into Langendorff-instrumented isolated rat hearts protect the mechanical functions of the myocardium during ischemia/reperfusion. The left ventricular developed pressure (LVDP) at the end of the reperfusion in the ATP-L group recovered to 72% of the baseline (preservation of the systolic function) compared to 26%, 40%, and 51% in the groups treated with Krebs-Henseleit (KH) buffer, empty liposomes (EL), and free ATP (F-ATP), respectively. The ATP-L-treated group also showed a significantly lower left ventricular end diastolic pressure (LVEDP; better preservation of the diastolic function) after ischemia/reperfusion than controls. After incubating the F-ATP and ATP-L with ATPase, the protective effect of the F-ATP was completely eliminated because of ATP degradation, while the protective effect of the ATP-L remained unchanged. Fluorescence microscopy confirmed the accumulation of liposomes in ischemic areas, and the net ATP in the ischemic heart increased with ATP-L. Our results suggest that ATP-L can effectively protect myocardium from ischemic/reperfusion damage.

Keywords: Isolated rat heart, Rabbit myocardial infarction, Mechanical functions, Ischemia, Reperfusion, ATP, Liposomes

1. Introduction

ATP levels drop by as much as 80% after 15 min in the cardiomyocytes during cardiac ischemia [1]. A similar time scale for the lowering of the intracellular ATP was observed during cardiac hypoxia and inhibition of glycolysis [2]. The concentration of ATP in the extracellular space in a well-perfused tissue is∼40 nM, [3] or∼105 times lower than the intracellular ATP concentration of 5-7 mM. In the continuing absence of the oxygen supply, both normal ATP supply and the temporary pathway for ATP production via glycolysis become rapidly depleted, ATP-dependent ion pumps in myocytes cease to function, cells lose their ion balance, swell, burst, and release their contents into the circulation. The mechanisms for the ischemia-induced myocardial failure include the depletion of ATP to 1.5-2.0 μmol/g wet weight and increase of intracellular Ca+ resulting in the increased myocardial contracture and cell death [4] by apoptosis or oncosis depending on duration of the ischemic stress and availability of the intracellular ATP [5].

The administration of the exogenous ATP might help in the restoration of its normal level in myocytes and cardioprotection. However, ATP has a very short half-life in the blood being hydrolyzed into ADP, AMP, and adenosine by extracellular ecto-nucleotidases [6]. Additionally, ATP is a hydrophilic and strongly charged anion, and cannot enter cells through the plasma membrane [6,7]. These limitations confine the direct use of the exogenous ATP as a therapeutic substrate. Thus, in order to generate a meaningful pharmacological response, alternative ways to deliver physiologically relevant amount of ATP into ischemic cardiomyocytes have to be found.

Liposomes are widely used as nanosized drug delivery vehicles [8]. The accumulation of liposomes as well as other nanoparticular drug carriers in the regions of experimental myocardial infarction was demonstrated [9-13], which proceeds via the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect[14,15]. Liposomes may also “plug” and “seal” the damaged myocyte membranes and protect cells against ischemic and reperfusion injury in vitro [16]. Thus, one can suggest that ATP-L can be used for the “passive” ATP delivery into the infarcted myocardium.

Some encouraging results with ATP-L in certain in vitro and in vivo models have been reported. ATP-L protected human endothelial cells from the energy failure in a cell culture model of sepsis [17].Ina brain ischemia model, ATP-L increased the number of ischemic episodes tolerated before brain electrical silence and death [7,18,19]. In a hypovolemic shock-reperfusion model in rats, ATP-L provided effective protection to the liver [20]. ATP-L improved rat liver energy state and metabolism during cold storage preservation [21,22]. Biodistribution studies with the ATP-L demonstrated their accumulation in the damaged myocardium [23]. Several methods to load ATP into liposomes have been described, such as the reverse phase evaporation and emulsification[7,19,20,23]. We have recently shown that the freezing-thawing method provides a high degree of ATP incorporation into liposomes [24].

Here, we present the data on the cardioprotective effect of the ATP-L on isolated rat hearts subjected to global ischemia in the Langendorff isolated heart model, which is a reliable system for measuring systolic (the ability of the heart to contract) and diastolic function (the ability of the heart to relax) of the left ventricle (LV) as indexes of cardiac function after global ischemia and reperfusion [25]. These results can be considered as a significant step towards the protection of the ischemic myocardium against damages resulting from an inadequate ATP supply.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Egg phosphatidylcholine (PC), cholesterol (Ch), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (mPEG2000-DSPE), 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethyl-ammonium-propane (DOTAP), and rhodamine-phosphatidylethanolamine (Rh-PE) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). ATP and adenosine-5V-triphosphatase (EC 3.6.1.3) from dog kidney (ATPase) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Fluorescein-isothiocyanate-labeled dextran (FITC-dextran) was purchased from Fluka Chemical (Buchs, Switzerland). All other chemicals and buffer components were of analytical grade.

2.2. Preparation of liposomes

To prepare ATP-L by the freezing-thawing method[24,26], chloroform solution of phosphatidylcholine (0.26 mmol), cholesterol (0.12 mmol), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethyleneglycol)-2000] (mPEG2000-DSPE) (1.8 μmol), and 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethyl-ammonium-propane (10.8 μmol) was evaporated, and the film formed was hydrated with 5 mL of 400 mM ATP in the KH buffer. The dispersion was frozen at -80 °C for 30 min followed by the thawing at 45°C for 5 min; this cycle was repeated 5 times. The liposomes were extruded 5 times through each of 800, 600, 400, and 200 nm pore size polycarbonate membranes (Whatman) to produce samples with a narrow size distribution. Non-encapsulated ATP was separated by dialysis against the KH buffer at 4 °C overnight. The liposomal formulations were diluted to a final concentration of 4 mg lipids/1 mg ATP/mL. For dose-dependency experiments, ATP-L sample was prepared with 10-fold decreased ATP content (0.1 mg ATP/mL). Control EL were prepared without adding ATP.

To prepare fluorescently labeled liposomes, 0.5 mol% of the membranotropic rhodamine-phosphatidylethanolamine (Rh-PE) was added to the lipid composition. The internal aqueous fluorescent marker, FITC-dextran (MW 4000 Da) was added to the KH buffer for liposome preparation. Non-encapsulated FITC-dextran was separated by gel-filtration on NAP™ columns (Amersham).

All liposomal preparations were supplemented with 1.7 mM CaCl2 prior to the infusion into the isolated heart.

2.3. Characterization of liposomes

The size and size distribution of EL and ATP-L were determined by dynamic light scattering using a Coulter N4 MD Submicron Particle Analyzer (Beckman-Coulter). Zeta-potentials of the liposome preparations were measured at 25 °C in water (0.08-0.015 mg lipid/mL) using a Zeta Plus z-potential analyzer (Brookhaven Instruments).

2.4. Excising and perfusing the heart, Langendorff apparatus, and experimental ischemia-reperfusion protocol

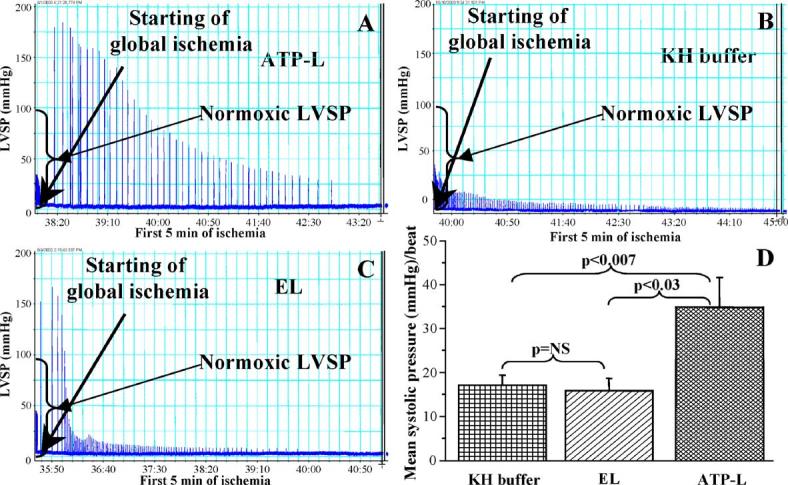

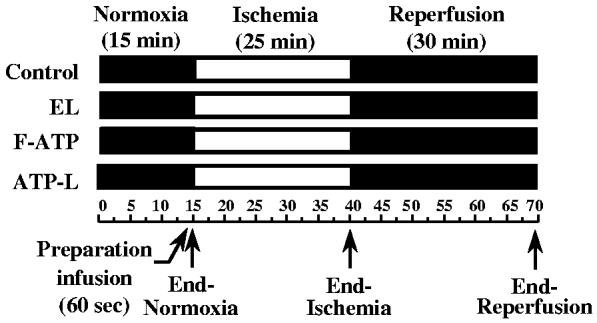

Sprague-Dawley rats (300-350 g) were anesthetized i.p. with sodium pentobarbital (80 mg/kg). The heart was excised and placed in ice-cold 0.9% NaCl. Within a minute from the time of excision, the heart was attached by the aorta onto the cannula of the Langendorff apparatus at 37 ± 1 °C. Thebesian drainage was removed via an apical drain placed through the LV apex, and a cannula was secured into the pulmonary artery for the coronary venous drainage. Isolated hearts were allowed for a 15 min stabilization period. Two pressure transducers PowerLab 4SP (ADInstruments) measured the coronary perfusion pressure (CPP) and LVDP/LVEDP. The LVDP is a physiological parameter indicating the ability of the heart to contract and develop pressure. It is defined as the difference between LV systolic pressure and LVEDP (an ability of the heart to relax) at the end of the relaxation phase of the heart. We have also monitored the ionotropic effect [characterizing the contractile function of the LV and expressed as an average of left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP; mm Hg) per beat] after the infusion of various preparations (Fig. 4). A positive ionotropic effect indicates a higher force of the myocardial contraction. The ± dp/dt values characterize the rate of the changes in heart contraction and relaxation. Pressure recordings were displayed on a digital recorder (Chart4, ADInstruments). LV balloon volume was adjusted to produce an initial LVEDP of 10 mm Hg, and this volume was kept constant throughout the experiment. These isolated, isovolumic (latex balloon-in-LV) rat heart preparations were retrogradely perfused through the aorta to the coronary arteries at a CPP of 80 mm Hg with the oxygenated KH buffer (with 1.7 mM CaCl2) at pH 7.4, aerated with the mixture of 95% O2and 5% CO2, and kept at 37 °C. The heart rate was maintained by pacing with a stimulator (Phipps and Bird) at a frequency of 5 Hz. Fig. 1 represents the schematic diagram of the experimental protocol. The liposomes were infused over a 1 min period, prior to the onset of ischemia. The calculated amount of the liposomal ATP administered into the isolated heart preparations was 9 ± 1 mmol/g wet weight of the heart (Mean ± SE). A global ischemia was immediately induced for 25 min by decreasing the perfusion pressure to zero within 60 s, and switching off the pacing. The hearts were then reperfused for 30 min at a CPP of 80 mm Hg with pacing.

Fig. 4.

Ionotropic effect of the infusion of ATP-L (A), KH buffer (B), EL (C), and summary graph of the mean LVSP per beat (D) during the first 5 min of global ischemia. (Mean ± SE), n= 7-10.

Fig. 1.

The schematic diagram of the experimental protocol.

2.5. Fluorescence microscopy

To follow liposome accumulation in the myocardium, liposomes with double fluorescent labels (Rh-PE in the membrane and FITC-dextran in the aqueous interior) were administered in ischemia/reperfusion experiment as described above. Approximately 3 mm thick heart sections were prepared and stained for the dehydrogenase activity by incubating them for 20 min at 40-45 °C with a 0.05% solution of Nitro Blue tetrasolium (NBT) in PBS, pH 7.4, which stained the infarcted areas [27]. Infarcted and non-infarcted tissue samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and superficial cryosections were discarded. The pictures of following sections were taken with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus) using FITC and rhodamine filters.

2.6. ATP level in ischemic myocardium

ATP in the heart tissue was determined by HPLC. At the very end of the perfusion, the heart sample was washed with liposome-free buffer to remove ATP-L from the vasculature. Tissue samples obtained after perfusion were quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C. To extract ATP, the heart tissue was homogenized with 0.66 M perchloric acid using a homogenizer (Yamato Scientific), vortexed for 1 min, and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min at 0 °C [28]. From this mixture, 1 mL of supernatant was mixed with 0.5 mL of 0.66 M potassium phosphate, and again vortexed and centrifuged. Fifty microliters of the supernatant was injected into the HPLC system using a 250-4.6 mm stainless steel column (Supelco) packed with the Discovery C18carrier (particle size of 5 μm, Supelco) at the following conditions: isocratic elution at room temperature with 0.1 M KH2PO4buffer, pH 6.0/methanol (96/4); flow-rate, 1 mL/min. The amount of ATP was measured by the UV absorbance at 254 nm. The retention time of ATP was 4.3 ± 0.2 min.

2.7. Ethics

Protocols for this study were approved by the IACUC, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA, and conform to the guidelines specified in the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication no. 85-23, revised 1985).

2.8. Statistical data analysis

Data analysis was carried out with the software package Microcal Origin, Version 6. Results were expressed as Mean ± Standard Error, n = 4-10 independent samples. Statistically significant differences were determined using the Student’s t-test and analysis of variance (group effect) (ANOVA) with p < 0.05 as a minimal level for significance.

3. Results

3.1. Liposome size, size distribution, and zeta-potential

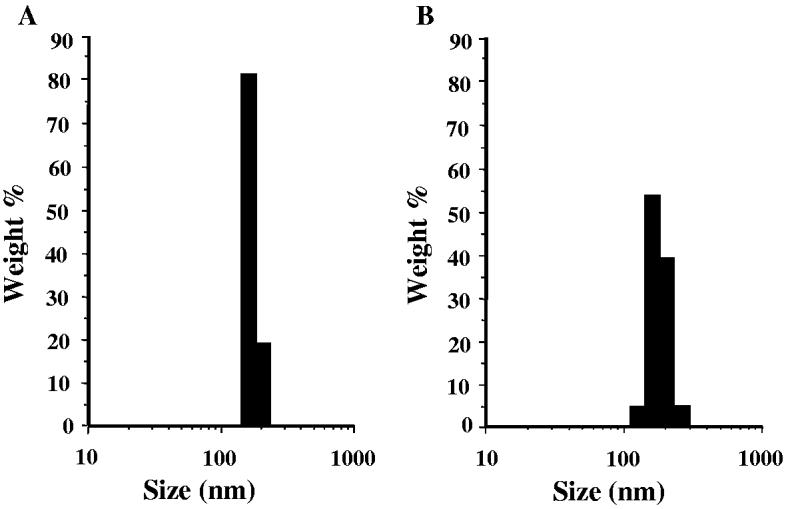

The freezing-thawing/extrusion method resulted in vesicles with a relatively high ATP encapsulation efficiency (ca. 0.40 μmol of ATP per μmol of total lipids) and with narrow size distribution for both EL [167.3 ± 45.8 nm (mean diameter ± SD) with polydispesity index of 0.109] and ATP-L [189.8 ± 45.5 nm (mean diameter ± SD) with polydispesity index of 0.085] (Fig. 2A,B). Zeta-potential values were virtually identical for EL and ATP-L (13.27 ± 0.59 and 12.91 ± 0.41 mV, respectively) indicating that ATP was encapsulated into liposomes rather than associated with the liposomal membrane.

Fig. 2.

The size and size distribution of EL (A) and ATP-L (B).

3.2. Systolic function of the myocardium in isolated heart model

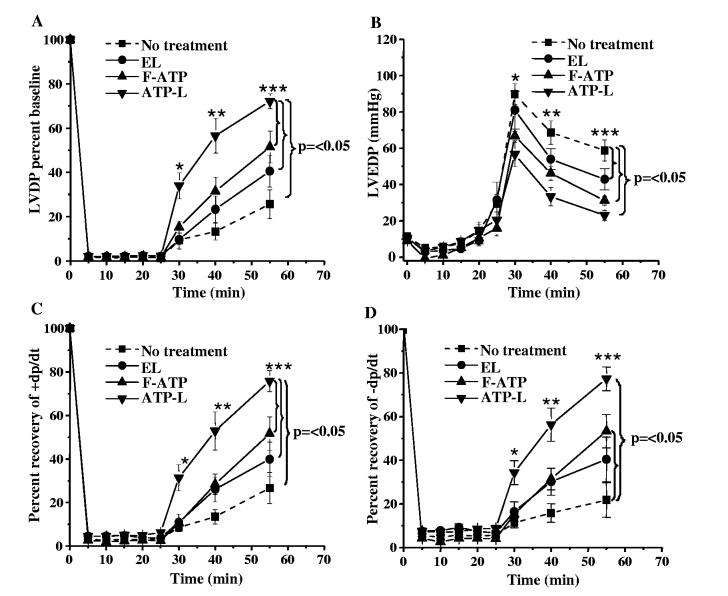

The LVDP baseline prior to ischemia in all the groups was 95 ± 6 mm Hg. At the onset of ischemia, all LVDP values decreased to less than 3 mm Hg (Fig. 3A). The group treated with ATP-L at an ATP concentration of 1 mg/mL exhibited the markedly best recovery of the LV contractile function of all groups. The LVDP after 15 min reperfusion in this ATP-L group was 51 ± 9 mm Hg (57% of baseline) as compared to 15 ± 4 (13% of baseline, p < 0.004), 22 ± 5 (23% of baseline, p < 0.03), and 28 ± 7mm Hg (31% of baseline, p < 0.03) in KH buffer, EL, and F-ATP groups, respectively. The LVDP at the end of reperfusion (30 min) in the ATP-L group was 65 ± 4 mm Hg (72% of baseline) as compared to 29 ± 8 (26% of baseline, p < 0.0007), 37 ± 6 (40% of baseline, p < 0.003), and 45 ± 9 mm Hg (51% of baseline, p < 0.05) in KH buffer, EL, and F-ATP group, respectively, (Fig. 3A). The changes in the developed pressure over time were accompanied by similar changes in ± dp/dt values. The recovery of the +dp/dt, the first derivative of contraction rate over time, in the ATP-L group (at 1 mg/mL ATP) was higher (76% baseline) than with KH buffer (27%; p < 0.0005), EL (40%; p < 0.001), and F-ATP (52%; p < 0.05) after 30 min reperfusion (Fig. 3C). Similarly, -dp/dt, the first derivative of relaxation rate over time, recovered to 77% baseline in the ATP-L, 22% in KH buffer ( p < 0.0005), 40% in EL ( p < 0.001), and 53% in F-ATP ( p < 0.05) groups after reperfusion (Fig. 3D). There was no significant difference between KH buffer and EL groups. An analysis of covariance (ANOVA) for the group effect on the LVDP was performed, which also indicated a significant ( p < 0.001) difference with an ± value of 12.3 with 3 degrees of freedom.

Fig. 3.

Effect of various preparations on LVDP (A) and LVEDP (B) values, as well as on ± dp/dt (C,D) after global ischemia and reperfusion in isolated rat heart (Mean ± SE), n = 7-10.

The phenomenon of LVDP recovery was ATP concentration-dependent, since a 10-fold decrease in the dose of ATP delivered by ATP-L (perfusate with 0.1 mg ATP/mL was used) resulted in decreased LVDP recovery after 30 min reperfusion to only 52 ± 15 mm Hg (the data are not shown in the Fig. 3 to keep it less busy). Fig. 4 represents the ionotropic effect of the infusion of various preparations on the LVSP during the first 5 min of global ischemia. In the ATP-L treated group the mean systolic pressure per beat was significantly higher (34 ± 7 mm Hg/beat) as compared to the KH buffer (17 ± 2 mm Hg/beat; p < 0.007) or EL (16 ± 3 mm Hg/beat; p < 0.03). This positive ionotropic effect of ATP-L infusion indicate that the ATP starts being delivered by the liposomes into the myocytes quickly, probably within a few minutes after the onset of ischemia, as seen in Fig. 4A. In contrast, the infusion of KH buffer or EL (Fig. 4B and C, respectively) did not show any positive ionotropic effect which is obvious as the ATP levels decrease by 80% in the initial few minutes of ischemia [1].

3.3. Diastolic function of the myocardium in isolated heart model

Under ischemia, LVEDP decreased to less than 5 mm Hg in all groups (Fig. 3B). Within the first 5 min of reperfusion, the LVEDP increased to 90 ± 6, 81 F10 ( p = NS), 67 ± 3( p < 0.005), and 57 ± 7mm Hg ( p < 0.003) in KH buffer, EL, F-ATP, and ATP-L (1 mg/mL ATP) groups, respectively. At the end of reperfusion, the LVEDP was significantly reduced to 23 ± 3 mm Hg in the ATP-L group (1 mg/mL ATP) as and 31 ± 2mmHg( p < 0.002) in KH buffer, EL, and F-ATP groups, respectively (no significant difference between KH buffer and EL groups). Again, the 10-fold decrease in ATP concentration resulted in higher LVEDP of 40 ± 5 mm Hg at the end of reperfusion. An analysis of covariance (ANOVA) for the group effect on the LVEDP also showed a significant ( p < 0.001) difference with an ± value of 11.2 with 3 degrees of freedom.

LVDP and LVEDP measurements demonstrated a substantial protective effect of the ATP-L on the systolic and diastolic functions after ischemia and reperfusion. It is worth mentioning here, that the use of the physical mixture of bworking concentrationsQ of EL and F-ATP produced the results close to that for F-ATP (the data not shown).

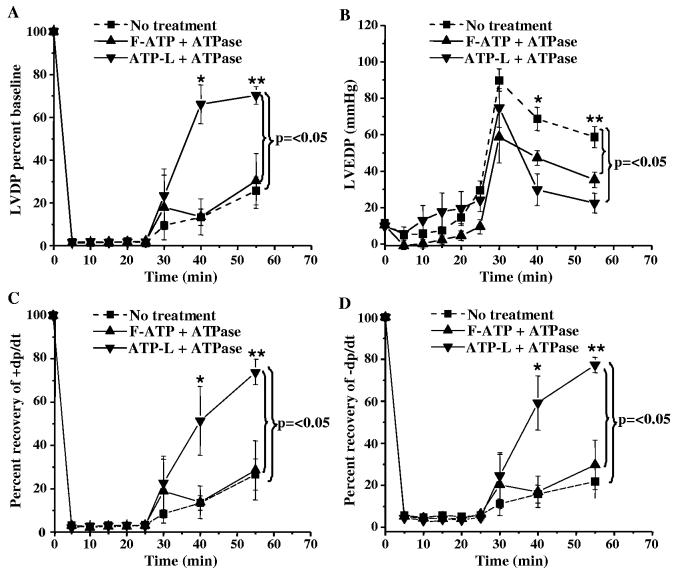

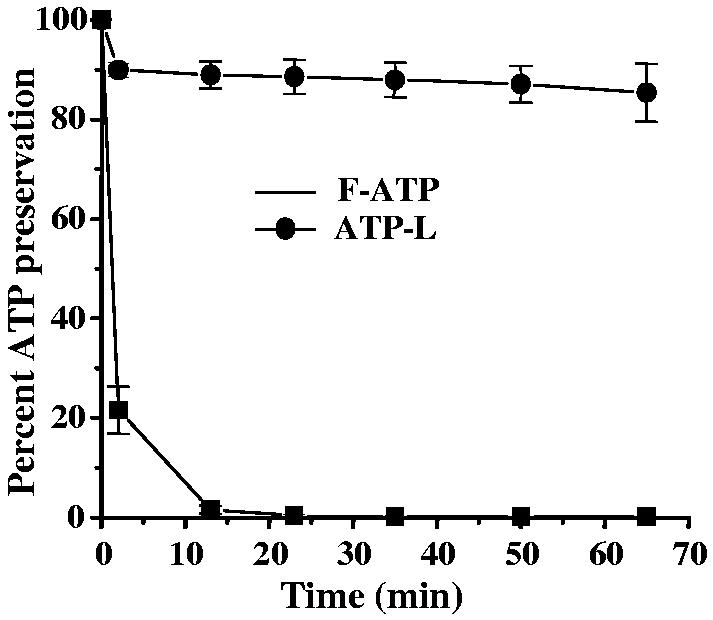

3.4. Effect of preincubation of ATP-L with ATPase

Both the F-ATP and ATP-L (1 mg/mL ATP) provided significant protection to the ischemic myocardium, the maximum effect still being observed with the ATP-L (Fig. 6). However, F-ATP can hardly protect the ischemic myocardium in vivo, since it is immediately hydrolyzed by extracellular enzymes [6]. We partially simulated in vivo conditions by preincubating F-ATP and ATP-L (same concentrations as ATP) with ATPase at 37 °C. The encapsulation into liposomes prevented the hydrolysis of ATP by ATPase 21% of the F-ATP remained non-hydrolized as compared to 90% in the case of ATP-L. After 25 min incubation, less than 0.5% of the F-ATP remained as compared to 85% in the case of ATP-L.

Fig. 6.

Protective effect of various preparations (incubated with ATPase for 60 min at 37 °C prior to infusion) on LVDP (A) and LVEDP (B) values, as well as ± dp/dt (C,D) after global ischemia and reperfusion in isolated rat heart (Mean ± SE), n =4.

After the treatment with the ATPase, the protective effect of the F-ATP on the ischemic myocardium was completely eliminated, while ATP-L (1 mg/mL ATP) still provided good recovery of LV contractile function (Fig. 6A). The LVDP at the end of reperfusion (30 min) in the ATP-L group was 68 ± 9 mm Hg (70% of the baseline) as compared to 27 ± 7 (28% of the baseline, p < 0.02) and 26 ± 12 mm Hg (27% of the baseline, p < 0.003) in KH buffer and bhydrolyzedQ F-ATP groups, respectively. Similarly, at the end of the reperfusion, LVEDP was significantly lower (23 ± 5 mm Hg) in the ATP-L group as compared to 59 ± 6 mm Hg in the KH buffer group ( p < 0.004) and 35 ± 4 mm Hg in the F-ATP group ( p < 0.03) (Fig. 6B). The recovery of the Fdp/dt values in the ATP-L group was significantly higher than in controls ( p < 0.005) (Fig. 6 C,D).

3.5. Liposome accumulation in ischemic myocardium in isolated heart model

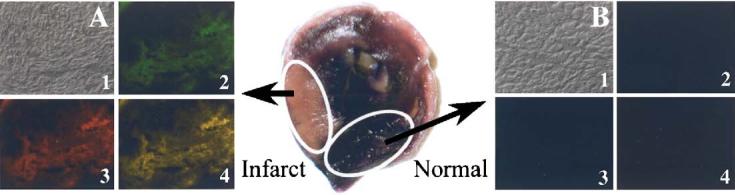

Using double-labeled fluorescent liposomes (Rh-PE and FITC-dextran) and cryosections of infarcted and normal myocardium, we observed the intense red and green fluorescence in the NBT-negative infarcted zone (Fig. 7A), indicating that liposomes accumulated in the infarct and delivered there their load (hydrophilic FITC-dextran). Neither the normal NBT-positive areas of the ischemic heart showed any fluorescence (Fig. 7B), nor did samples from a non-ischemic heart (images not shown).

Fig. 7.

Microscopy of 7 μm thick heart cryosections fixed with 4% formaldehyde, washed with PBS, and mounted with Flour mounting media (Trevigen). A — Extensive association of Rh-PE and FITC fluorescence with infarcted (pink, NBT-negative) tissue; B — Lack of fluorescence associated with normal (dark, NBT-positive) tissue. 1 — Transmission microscopy; 2 — fluorescence microscopy with FITC filter; 3 — fluorescence microscopy with rhodamine filter; 4 — superposition of (2) and (3).

3.6. ATP level in ischemic myocardium in isolated heart model

The ATP level in ventricular tissue (cardiomyocytes) at the end of reperfusion in the ATP-L (1 mg/mL ATP) group was 69.2 ± 4.6 μg/100 mg wet weight (1.25 μmol/g) or approximately 50% higher ( p < 0.05) compared to 46.4 ± 1.5 μg (0.84 μmol/g) in the KH buffer group (similar ATP concentrations were reported earlier for rat hearts after ischemia-reperfusion [29]).

4. Discussion

Our experiments clearly demonstrated a pronounced protective effect of the ATP-L (1 mg/mL ATP in the isolated rat heart perfusion system) on the functions (systolic and diastolic) of the myocardium during acute myocardial ischemia and reperfusion in isolated rat heart. Assuming that the use of ATP-L eventually resulted in an increased level of ATP in cardiomyocytes, 25 min of ischemia in the isolated heart model already provided a sufficient time for ATP-L to accumulate in the ischemic area via the EPR effect and bunloadQ ATP in concentrations sufficient to protect ischemic cells. This is in agreement with earlier reports that liposomes are rapidly taken up by the hearts during the Langendorff perfusion [30] or protect the rat liver during 30 min of hypovolumic shock [20].

In our study, we used the freezing-thawing method of ATP-L preparation because of its simplicity, high encapsulation efficiency (40 mol% in our case), and the absence of organic solvents [24]. The increased encapsulation of ATP into liposomes by this method may be explained by the formation of transient pores in the liposomal membrane, which allows for the ATP entry from the outside into the inside until the equilibrium is achieved [31].

Circulation time of liposomes in vivo can be increased by grafting their surface with poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), which inhibits liposome opsonization and subsequent elimination [32-35]. On the other hand, high concentration of the PEG on the liposome surface may hinder the interaction of liposomes with target cells and drug release. Therefore, we have used a relatively small amount of PEG on the liposomal surface (0.5 mol% of mPEG2000-DSPE) aiming to achieve both, a somewhat extended circulation time within the perfusion system and easiness of interaction with cells.

In our experiments, the use of ATP-L (1 mg/mL ATP) in the isolated heart model allowed for substantial normalization of LVDP and LVEDP after ischemia/reperfusion (Fig. 3A,B). The recovery of the contractile and relaxation functions proceeds with a similar rate as follows from the close values of +dp/dt and - dp/dt. Certain beneficial (though smaller) effects could also be noticed after the administration of the EL and F-ATP (Fig. 3A,B).

However, protective mechanisms in all these cases may differ. Thus, the beneficial effect of the EL may be explained by the earlier demonstrated non-specific “plugging and sealing” of the damaged cell membranes [16]. At the same time, the cardioprotection of the isolated heart by the F-ATP that cannot enter cardiomyocytes, may involve endogenous physiological mechanisms, since the role of the ATP in the heart is not restricted to energy-requiring processes inside cells. Extracellular ATP is an important signal molecule [3,37], and F-ATP could provide a certain protection to the ischemic myocardium by getting incorporated into the existing mechanisms involving the chain of interstitial adenine nucleotides, interstitial enzymes, myocyte purinoreceptors, and KATP channels as a final common pathway of endogenous cardioprotection [3,6,36,37]. Thus, the intravascular administration of ATP has been shown to induce a significant coronary vasodilation in the isolated heart[37-39]. Still, whatever mechanisms of the protective action of F-ATP might be, it can hardly be considered as an in vivo cardioprotector because of fast ATP dephosphorylation in the circulation by ecto-nucleotidases located on the surface of myocytes [3,6,40,41] via an efficient and “almost instantaneous” process [37]. This was confirmed by the complete abolition of the protective effect of F-ATP with ATPase in our experiment (see Fig. 6A,B) which precludes its use in vivo.

Contrary to this, the ATP-L seems to protect the heart through the different mechanisms and may directly deliver ATP into the myocytes, thus recovering heart mechanical functions after ischemia/reperfusion. At the end of experiment, the ATP-L-treated group (1 mg/mL ATP) showed significantly higher recovery of LVDP and the lowest rise of the LVEDP than all controls. Unlike F-ATP, ATP-L was not affected by the ATPase treatment and still had significant cardioprotective effect. Moreover, the observation in the first 5 min of global ischemia revealed the pronounced positive ionotropic effect of ATP-L infusion, which supports our hypothesis on the direct delivery of liposomal ATP into the ischemic cardiomyocytes, thereby protecting the mechanical functions of the myocardium.

The ability of the liposomes to cross the biological barriers, such as capillary endothelium, and deliver ATP directly into the cell by transporting themselves through endothelial tight junction opening and increased endothelial endocytosis was clearly shown[42,43]. The opening of the endothelial tight junctions is the primary mechanism through which liposomes reach the tissue in the ischemic brain [7,44] and in the liver [20]. Enhanced permeability and retention effect can also facilitate liposome extravasation into ischemic myocardium through damaged blood vessels[11-15]. It was also reported that liposomes could cross a continuous wall of myocardial capillaries in the isolated heart through endocytosis [45]. In an ischemic myocardium, liposomes were found in the cytoplasm of both cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells [9].

The hypothesis that the selective accumulation of ATP-L in the ischemic tissue and direct ATP delivery to ischemic cells are responsible for myocardial protection was confirmed by the fluorescence microscopy of heart cryosections after the perfusion with liposomes labeled with Rh-PE and loaded with FITC-dextran. Fig. 7A shows an extensive association of liposomes (red fluorescence) and intraliposomal load (green fluorescence) with ischemic areas, but not with the normal myocardium (Fig. 7B). The presence of FITC-dextran in the infarcted zone indicates that liposomes can deliver their hydrophilic load, such as ATP, into the ischemic myocardium. An increase by almost 50% in the levels of ATP found in ATP-L-treated hearts (liposomal ATP accumulated both in the interstitium via the EPR effect and in ischemic cardiomyocytes) supports our hypothesis. Although, the amount of liposomal ATP actually delivered into the ischemic myocytes may be not very high, it nevertheless may btip the “alance” of the ischemic injury and provide cardioprotection.

In conclusion, in the isolated rat heart model, ATP-L effectively protect ischemic myocardium from the ischemia/reperfusion damage and significantly improve both systolic and diastolic functions after ischemia and reperfusion. Although the experimental setup used in our work is far from the real clinical situation, nevertheless, we have obtained a clear proof that ATP-L can deliver their ATP load to/into ischemic cardiomyocytes and diminish their damage. If this protection could be further enhanced by using immuno-targeted and/or fusogenic liposomes, and if ATP-L can protect ischemic myocardium in vivo in animals with an acute experimental myocardial infarction, are the subjects of our current research.

Fig. 5.

Prevention of ATP hydrolysis by ATPase (adenosine-5′-triphosphatase EC 3.6.1.3 from dog kidney) at 37 °C by encapsulation in liposomes. (Mean ± SE), n=3.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the NIH grant RO1 HL55519 to Vladimir Torchilin. Authors acknowledge the technical support of V. Thakkar and F. Gadkari.

Footnotes

- ATP

- adenosine-5′-triphosphate

- ATPase

- adenosine-5′-triphosphatase

- ATP-L

- liposomes loaded with ATP

- F-ATP

- free ATP in Krebs-Henseleit buffer

- EL

- empty liposomes

- CPP

- coronary perfusion pressure

- LV

- left ventricle

- LVDP

- left ventricular developed pressure

- LVEDP

- left ventricular end diastolic pressure

- LVSP

- left ventricular systolic pressure

- KH

- Krebs-Henseleit

- EPR

- enhanced permeability and retention

- Rh-PE

- rhodamine-phosphatidylethanolamine

- FITC-dextran

- fluorescein-isothiocyanate-labeled dextran

- PEG

- poly(ethylene glycol)

References

- [1].Kingsley PB, Sako EY, Yang MQ, Zimmer SD, Ugurbil K, Foker JE, From AH. Ischemic contracture begins when anaerobic glycolysis stops: a 31P-NMR study of isolated rat hearts. Am. J. Physiol. 1991;261:H469–H478. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.2.H469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Allen DG, Morris PG, Orchard CH, Pirolo JS. A nuclear magnetic resonance study of metabolism in the ferret heart during hypoxia and inhibition of glycolysis. J. Physiol. 1985;361:185–204. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kuzmin AI, Lakomkin VL, Kapelko VI, Vassort G. Inter-stitial ATP level and degradation in control and postmyocardial infarcted rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275:C766–C771. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.3.C766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Flameng W. New strategies for intraoperative myocardial protection. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 1995;10:577–583. doi: 10.1097/00001573-199511000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Leist M, Single B, Castoldi AF, Kuhnle S, Nicotera P. Intracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) concentration: a switch in the decision between apoptosis and necrosis. J. Exp. Med. 1997;185:1481–1486. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.8.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gordon JL. Extracellular ATP: effects, sources and fate. Biochem. J. 1986;233:309–319. doi: 10.1042/bj2330309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Puisieux F, Fattal E, Lahiani M, Auger J, Jouannet P, Couvreur P, Delattre J. Liposomes, an interesting tool to deliver a bioenergetic substrate (ATP). In vitro and in vivo studies. J. Drug Target. 1994;2:443–448. doi: 10.3109/10611869408996820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lasic DD, Papahajopoulos D. Medical Application of Liposomes. Elsevier, Amsterdam; The Netherlands: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Caride VJ, Zaret BL. Liposome accumulation in regions of experimental myocardial infarction. Science. 1977;198:735–738. doi: 10.1126/science.910155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Palmer TN, Caride VJ, Caldecourt MA, Twickler J, Abdullah V. The mechanism of liposome accumulation in infarction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1984;797:363–368. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(84)90258-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lukyanov AN, Hartner WC, Torchilin VP. Increased accumulation of PEG-PE micelles in the area of experimental myocardial infarction in rabbits. J. Control. Release. 2004;94:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Mueller TM, Marcus ML, Mayer HE, Williams JK, Hermsmeyer K. Liposome concentration in canine ischemic myocardium and depolarized myocardial cells. Circ. Res. 1981;49:405–415. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Caride VJ, Twickler J, Zaret BL. Liposome kinetics in infarcted canine myocardium. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1984;6:996–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Maeda H, Wu J, Sawa T, Matsumura Y, Hori K. Tumor vascular permeability and the EPR effect in macromolecular therapeutics: a review. J. Control. Release. 2000;65:271–284. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Maeda H. The enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect in tumor vasculature: the key role of tumor-selective macromolecular drug targeting. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 2001;41:189–207. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2571(00)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Khaw BA, Torchilin VP, Vural I, Narula J. Plug and seal: prevention of hypoxic cardiocyte death by sealing membrane lesions with antimyosin-liposomes. Nat. Med. 1995;1:1195–1198. doi: 10.1038/nm1195-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Han YY, Huang L, Jackson EK, Dubey RK, Gillepsie DG, Carcillo JA. Liposomal atp or NAD+ protects human endothelial cells from energy failure in a cell culture model of sepsis. Res. Commun. Mol. Pathol. Pharmacol. 2001;110:107–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Laham A, Claperon N, Durussel JJ, Fattal E, Delattre J, Puisieux F, Couvreur P, Rossignol P. Liposomally-entrapped ATP: improved efficiency against experimental brain ischemia in the rat. Life Sci. 1987;40:2011–2016. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(87)90292-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Laham A, Claperon N, Durussel JJ, Fattal E, Delattre J, Puisieux F, Couvreur P, Rossignol P. Liposomally entrapped adenosine triphosphate. Improved efficiency against experimental brain ischaemia in the rat. J. Chromatogr. 1988;440:455–458. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)94549-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Konno H, Matin AF, Maruo Y, Nakamura S, Baba S. Liposomal ATP protects the liver from injury during shock. Eur. Surg. Res. 1996;28:140–145. doi: 10.1159/000129451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Neveux N, De Bandt JP, Fattal E, Hannoun L, Poupon R, Chaumeil JC, Delattre J, Cynober LA. Cold preservation injury in rat liver: effect of liposomally-entrapped adenosine triphosphate. J. Hepatol. 2000;33:68–75. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Neveux N, De Bandt JP, Chaumeil JC, Cynober L. Hepatic preservation, liposomally entrapped adenosine triphosphate and nitric oxide production: a study of energy state and protein metabolism in the cold-stored rat liver. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2002;37:1057–1063. doi: 10.1080/003655202320378266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Xu GX, Xie XH, Liu FY, Zang DL, Zheng DS, Huang DJ, Huang MX. Adenosine triphosphate liposomes: encapsulation and distribution studies. Pharm. Res. 1990;7:553–557. doi: 10.1023/a:1015837321087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Liang W, Levchenko TS, Torchilin VP. Encapsulation of ATP into liposomes by different methods: optimization of the procedure. J. Microencapsul. 2004;21:251–261. doi: 10.1080/02652040410001673900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Galinanes M, Hearse DJ. Assessment of ischemic injury and protective interventions: the Langendorff versus the working rat heart preparation. Can. J. Cardiol. 1990;6:83–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Pick U. Liposomes with a large trapping capacity prepared by freezing and thawing of sonicated phospholipid mixtures. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1981;212:186–194. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(81)90358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Narula J, Petrov A, Pak KY, Lister BC, Khaw BA. Very early noninvasive detection of acute experimental nonreperfused myocardial infarction with 99mTc-labeled glucarate. Circulation. 1997;95:1577–1584. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.6.1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Teerlink T, Hennekes M, Bussemaker J, Groeneveld J. Simultaneous determination of creatine compounds and adenine nucleotides in myocardial tissue by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 1993;214:278–283. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Khogali SE, Harper AA, Lyall JA, Rennie MJ. Effects of L-glutamine on post-ischaemic cardiac function: protection and rescue. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:819–827. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kayawake S, Kako KJ. Association of liposomes with the isolated perfused rabbit heart. Basic Res. Cardiol. 1982;77:668–681. doi: 10.1007/BF01908318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mayer LD, Hope MJ, Cullis PR, Janoff AS. Solute distributions and trapping efficiencies observed in freeze-thawed multilamellar vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1985;817:193–196. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(85)90084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Klibanov AL, Maruyama K, Torchilin VP, Huang L. Amphipathic polyethyleneglycols effectively prolong the circulation time of liposomes. FEBS Lett. 1990;268:235–237. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81016-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Blume G, Cevc G. Liposomes for the sustained drug release in vivo. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1990;1029:91–97. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(90)90440-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Torchilin VP, Trubetskoy VS. Which polymers can make nanoparticulate drug carriers long-circulating? Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1995;16:141–155. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lasic DDM, Stealth Liposomes F. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- [36].O’Rourke B. Myocardial K(ATP) channels in preconditioning. Circ. Res. 2000;87:845–855. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.10.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Korchazhkina O, Wright G, Exley C. No effect of aluminium upon the hydrolysis of ATP in the coronary circulation of the isolated working rat heart. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1999;76:121–126. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(99)00123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Erga KS, Seubert CN, Liang HX, Wu L, Shryock JC, Belardinelli L. Role of A(2A)-adenosine receptor activation for ATP-mediated coronary vasodilation in guinea-pig isolated heart. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:1065–1075. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gorman MW, Ogimoto K, Savage MV, Jacobson KA, Feigl EO. Nucleotide coronary vasodilation in guinea pig hearts. Am. J. Physiol., Heart Circ. Physiol. 2003;285:H1040–H1047. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00981.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Plesner L. Ecto-ATPases: identities and functions. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1995;158:141–214. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62487-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Yagi K, Shinbo M, Hashizume M, Shimba LS, Kurimura S, Miura Y. ATP diphosphohydrolase is responsible for ecto-ATPase and ecto-ADPase activities in bovine aorta endothelial and smooth muscle cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1991;180:1200–1206. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81323-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Chapat S, Frey V, Claperon N, Bouchaud C, Puisieux F, Couvreur P, Rossignol P, Delattre J. Efficiency of liposomal ATP in cerebral ischemia: bioavailability features. Brain Res. Bull. 1991;26:339–342. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(91)90004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Laham A, Claperon N, Durussel JJ, Fattal E, Delattre J, Puisieux F, Couvreur P, Rossignol P. Intracarotidal administration of liposomally-entrapped ATP: improved efficiency against experimental brain ischemia. Pharmacol. Res. Commun. 1988;20:699–705. doi: 10.1016/s0031-6989(88)80117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kuroiwa T, Shibutani M, Okeda R. Blood-brain barrier disruption and exacerbation of ischemic brain edema after restoration of blood flow in experimental focal cerebral ischemia. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl) 1988;76:62–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00687681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Mixich F, Mihailescu S. Liposome microcapsules; an experimental model for drug transport across the blood-brain barrier. In: deBoer B, Sutanto W, editors. Drug Transport Across the Blood-Brain Barrier. Harwood Acad. Publ; GMBH, Amsterdam: 1997. pp. 201–213. [Google Scholar]