Abstract

Background

Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging with fluorine-18 (18F) Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) and flow tracer such as Rubidium-82 (82Rb) is an established method for evaluating an ischemic but viable myocardium. However, the high cost of PET imaging restricts its wider clinical use. Therefore, less expensive 18F FDG single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging has been considered as an alternative to 18F FDG PET imaging. The purpose of the work is to compare SPECT with PET in myocardial perfusion/viability imaging.

Methods

A nonuniform RH-2 thorax-heart phantom was used in the SPECT and PET acquisitions. Three inserts, 3 cm, 2 cm and 1 cm in diameter, were placed in the left ventricular (LV) wall to simulate infarcts. The phantom acquisition was performed sequentially with 7.4 MBq of 18F and 22.2 MBq of Technetium-99m (99mTc) in the SPECT study and with 7.4 MBq of 18F and 370 MBq of 82Rb in the PET study. SPECT and PET data were processed using standard reconstruction software provided by vendors. Circumferential profiles of the short-axis slices, the contrast and viability of the inserts were used to evaluate the SPECT and PET images.

Results

The contrast for 3 cm, 2 cm and 1 cm inserts were for 18F PET data, 1.0 ± 0.01, 0.67 ± 0.02 and 0.25 ± 0.01, respectively. For 82Rb PET data, the corresponding contrast values were 0.61 ± 0.02, 0.37 ± 0.02 and 0.19 ± 0.01, respectively. For 18F SPECT the contrast values were, 0.31 ± 0.03 and 0.20 ± 0.05 for 3 cm and 2 cm inserts, respectively. For 99mTc SPECT the contrast values were, 0.63 ± 0.04 and 0.24 ± 0.05 for 3 cm and 2 cm inserts respectively. In SPECT, the 1 cm insert was not detectable. In the SPECT study, all three inserts were falsely diagnosed as "viable", while in the PET study, only the 1 cm insert was diagnosed falsely "viable".

Conclusion

For smaller defects the 99mTc/18F SPECT imaging cannot entirely replace the more expensive 82Rb/18F PET for myocardial perfusion/viability imaging, due to poorer image spatial resolution and poorer defect contrast.

Background

Fluorine-18 (18F) Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging has been considered as an alternative to 18F FDG positron emission tomography (PET) imaging for evaluating injured but viable myocardium [1,2]. SPECT 18F imaging is sometimes performed as simultaneous Technetium-99m sestamibi (99mTc MIBI)/18F FDG perfusion/viability myocardial studies [3,4]. The main limitations of this technique are poor resolution of the 18F and 99mTc SPECT images and, when acquired simultaneously, degradation of the 99mTc MIBI images due to 18F downscatter to the 99mTc window. The 18F images are also influenced by high septal penetration and poor sensitivity, due to the limited stopping power of the detector crystal in standard gamma cameras [5]. In PET centres without a cyclotron, sequential Rubidium-82 (82Rb) and 18F FDG perfusion/viability myocardial imaging are the most appropriate, because of the availability of both isotopes [6-10]. 82Rb is a potassium analog that, like Thalium-201, is extracted by living cells. It is produced from a commercially available, FDA approved strontium-82 generator, which must be replenished 13 times a year. The short half-life of 82Rb allows repeated acquisitions every 10 minutes. Neither, 18F FDG or 82Rb require expensive on-site cyclotrons, as are needed with 13N ammonia and 15O oxygen. Also, most health care providers reimburse for 82Rb perfusion imaging, and more recently for 18F FDG viability myocardial imaging.

The objective of our work was to compare 18F SPECT with PET in myocardial perfusion/viability imaging in the classification of simulated myocardial defects for "viability" according to commonly applied criteria.

Methods

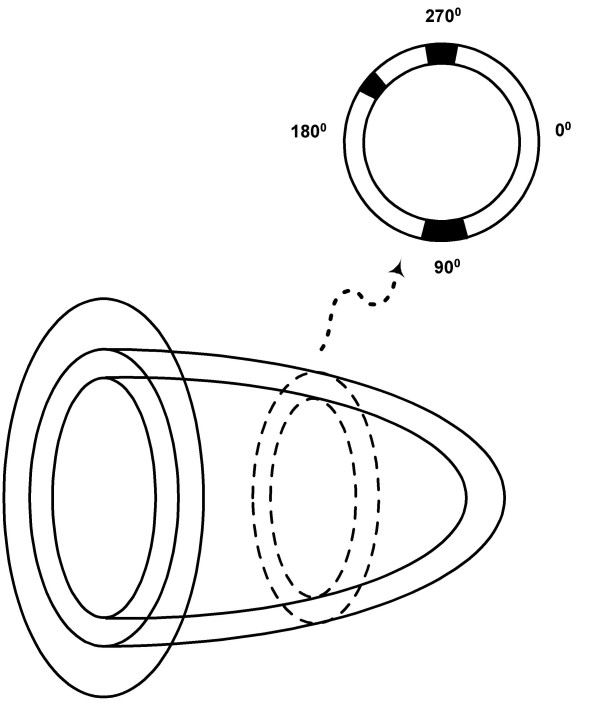

A nonuniform RH-2 thorax-heart phantom (Kyoto Scientific Speciment Co., LTD, Kyoto, Japan) (Fig. 1) was used in SPECT and PET acquisitions. Three inserts, 3 cm, 2 cm and 1 cm in diameter, were placed in the left ventricular (LV) wall to simulate small transmural infarcts (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

RH-2 thorax-heart phantom. A) In a left ventricular wall three inserts, 1 cm, 2 cm and 3 cm in diameter were placed in the same short-axis plane. B) Cardiac phantom is placed in water. Left ventricular wall is connected by Teflon tubes to remote filling system. Teflon rod simulates spine and sawdust simulates lungs.

Figure 2.

Position of inserts. The 3 cm insert was placed at 90 degrees, 1 cm insert at 200 degrees and 2 cm insert at 270 degrees.

SPECT acquisitions were performed on a dual headed system (T22 gamma camera, SMV, Twinsburg, Ohio) with ultra-high-energy (UHE) collimator. The energy resolution of the system at 140 keV is 9.8%, and at 511 keV is 7.8%. The thickness of the NaI(Tl) crystal is 0.9525 cm (3/8"). A step-and-shoot mode was used for SPECT acquisitions, with a 64 × 64 acquisition and processing frame matrix size and zoom of 1.5. The time per frame was 40 sec. The 64 frames were acquired over 360°. The radius of rotation for the phantom study was 21 cm, which is also a typical radius for our clinical SPECT acquisitions. The pixel size in the acquisition and reconstructed images was 6.08 mm. SPECT data were processed using standard reconstruction software based on a filtered backprojection method. A Butterworth filter of 5th order and cut-off frequency of 0.25 cycles/pixel was used in the reconstruction for all studies. Neither attenuation nor scatter correction was performed.

The UHE parallel-hole collimator, used for the 18F SPECT imaging, has hexagonal holes 3.4 mm in diameter and 65.0 mm in length, with a septal thickness of 3.0 mm. The collimator cores are mounted in an all-lead frame designed for 511 keV imaging. Planar resolution as a function of distance for the UHE collimator, measured in air with a 99mTc point source was FWHM = 3.9 mm, 10.6 mm, and 14.0 mm for 0 cm, 10 cm and 15 cm distance, respectively. The same planar resolution measured with an 18F point source gave FWHM = 5.3 mm, 13.9 mm, and 18.2 mm for 0 cm, 10 cm and 15 cm distance, respectively [11]. The standard deviation was less than 0.5 mm in all measurements and was obtained from three measurements. This shows that planar resolution for the UHE collimator is better for 99mTc than for 18F. Septal penetration for the UHE collimator is 6.5% and for the low-energy-high-resolution collimator is 0.50% [5]. The quoted septal penetration values were calculated for only single septi. Actual septal penetration in clinical situations may account for 30%–50% of detected events [3].

A GE ADVANCE (General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) PET system was used in 2D mode for PET acquisitions. The system has 18 detector rings and 12,096 bismuth germanate (BGO) 4 × 8 × 30 mm crystals. In 2D mode, the system uses a tungsten collimator 1 × 120 mm in size. The axial field of view is 15.2 cm. It is covered by 35 image planes. The axial sampling interval is 4.25 mm. The transaxial field of view is 55.0 cm. The coincidence window width is 12.5 ns and energy window is 300–650 keV. All 2D PET acquisitions were performed in high sensitivity (HS) mode. The resolution of our PET system was measured using an 18F line source and for HS mode, FWHM = 4.44 ± 0.04 mm in the tangential direction and FWHM = 4.85 ± 0.08 mm in the radial direction. The PET images were reconstructed using a filtered backprojection reconstruction method and Hanning smoothing filter with an 0.5 cycles/pixel cutoff. The matrix size was 128 × 128 and the pixel size was 4.29 mm. Attenuation correction using an 8-min transmission scan was applied in the PET studies. Also, Bergstrom [12] scatter correction, provided by the vendor, was applied.

All phantom acquisitions were single-isotope studies in order to avoid down-scatter. The SPECT study was performed with 7.4 MBq of 18F and 22.2 MBq of 99mTc and the PET study with 7.4 MBq of 18F and 370 MBq of 82Rb. These activities were injected into the phantom LV wall, which with the three inserts had a volume of 140 ml. Consequently, the radioactivity concentrations in the LV wall were 52.9 kBq/ml for 18F, 158.6 kBq/ml for 99mTc and 2.64 MBq/ml for 82Rb.

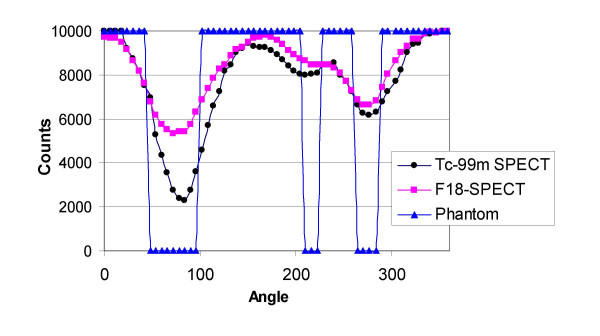

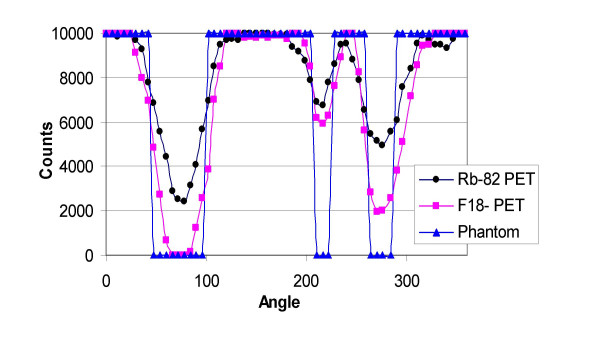

Circumferential profiles of the short-axis slices (figs. 3 and 4), the contrast, and the defect severity of the inserts were used to evaluate the SPECT and PET images. The contrast value was calculated as a ratio C = (A-B)/(A+B), where A and B are the average activities in region-of-interest (ROI) covering the normal and cold areas, respectively. In the SPECT study, 3 × 3 pixel (region-of-interest) ROIs covering 333 mm2 were used, and in the PET study 4 × 4 pixel ROIs covering 294 mm2 were used. The different size ROIs in SPECT and PET were used to approximately cover the same area, although the PET ROI was slightly smaller. In all studies, three adjacent short-axis slices were used, and their average contrast value and standard deviation were calculated.

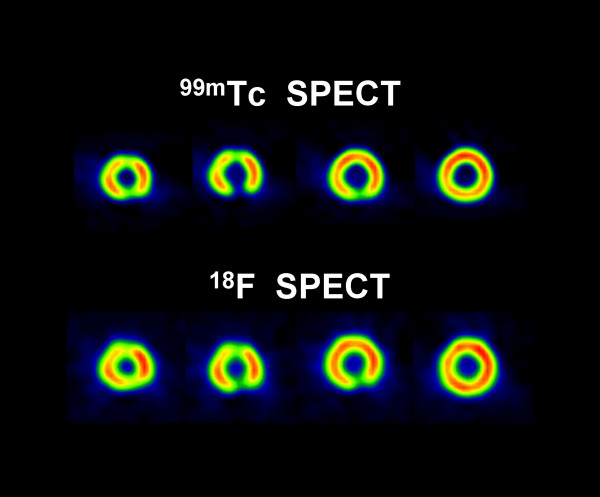

Figure 3.

Short-axis slices. Short-axis slices in the 99mTc/18F SPECT cardiac phantom study.

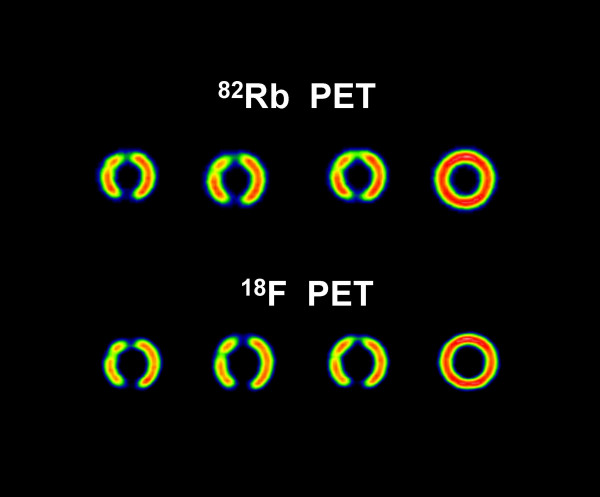

Figure 4.

Short-axis slices. Short-axis slices in the 82Rb/18F PET cardiac phantom study.

Two criteria were used to determine "viability" or "nonviability" [13-24]. First, for each isotope images, i.e., 99mTc, 82Rb and 18F images, if the minimum value in the lesion (MIN) was less than 50% of the maximum LV value (MAX), the lesion was considered to be nonviable. In addition to the above mentioned criterion for nonvaibility, in the SPECT study, the minimum lesion value in the 18F image (MIN(18F)) should be equal to or less than the same corresponding minimum lesion value in the 99mTc image (MIN(99mTc)). In the PET study, the minimum lesion value in the 18F image should be equal to or less than the same the minimum lesion value in the 82Rb image (MIN(82Rb)). If the MIN(18F) is greater than the same lesion MIN(99mTc) or MIN(82Rb), for SPECT or PET study, respectively, then the lesion is considered viable (mismatch pattern).

By definition, the inserts, not containing any activity, were considered as a "nonviable" gold standard.

Results

Figures 3 and 4 show short axis slices from the 99mTc/18F SPECT study and from the 82Rb/18F PET study, respectively. In the SPECT study (Fig. 3) the 99mTc images have better resolution and contrast than the corresponding 18F images [5,11]. However, in the PET study (Fig. 4) the situation is the opposite, i.e. the 18F images have better resolution and contrast compared with the corresponding 82Rb images. Comparing the SPECT with PET images (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4) one can see that PET images have much better resolution and, except for the 99mTc 3 cm insert, the contrast values are better than in the SPECT images, regardless of the isotope used. For 18F PET data the contrast for 3 cm, 2 cm and 1 cm inserts was 1.0 ± 0.01, 0.67 ± 0.02 and 0.25 ± 0.01, respectively. For 82Rb PET data the corresponding contrast values were 0.61 ± 0.02, 0.37 ± 0.02, and 0.19 ± 0.01, respectively. For 18F SPECT the contrast values were, 0.31 ± 0.03 and 0.20 ± 0.05 for 3 cm and 2 cm inserts respectively. For 99mTc SPECT the contrast values were, 0.63 ± 0.04 and 0.24 ± 0.05 for 3 cm and 2 cm inserts respectively. In the SPECT study the 1 cm insert was not visually detectable (Fig. 3 and Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Circumferential profiles. Circumferential profiles from short-axis slices shown in fig. 3.

The total number of counts was 2.5 times higher in the PET 18F study vs. the SPECT 18F study. The total number of counts in the PET study was calculated as total prompt counts minus total delays (randoms), and they include scatter events.

Figures 5 and 6 show circumferential profiles from the short-axis slices shown in fig. 3 and fig. 4, respectively, normalized to 10,000 counts. Normalization provided easier calculations of nonviability/viability of the insert areas, using the criteria described above. Table 1 gives minimum values in the insert areas as percentage of the maximum, i.e. 10,000 values. Based on the criteria described in the methods section, nonviability/viability for the inserts were calculated and presented in Table 2.

Figure 6.

Circumferential profiles. Circumferential profiles from short-axis slices shown in fig. 4.

Table 1.

COMPARISON OF SPECT 99mTc/18F AND PET 82Rb/18F IN CARDIAC PHANTOM STUDY*

| 1 cm insert | 2 cm insert | 3 cm insert | |

| 18F SPECT | 85% | 66% | 54% |

| 99mTc SPECT | 80% | 62% | 23% |

| 18F PET | 60% | 20% | 0% |

| 82Rb PET | 68% | 50% | 24% |

* Percentage of maximum values

Table 2.

Clinical diagnosis

| 1 cm insert | 2 cm insert | 3 cm insert | |

| 99mTc/18F SPECT | VIABLE | VIABLE | VIABLE |

| 82Rb/18F PET | VIABLE | NONVIABLE | NONVIABLE |

Based on the 99mTc/18F dual-isotope criteria used (Tables 1 and 2), SPECT failed, for all three inserts, to provide the correct result (nonviable), while the 82Rb/18F PET study correctly identified the two larger nonviable lesions. The region of the 1 cm insert was falsely diagnosed as viable by using the criteria described in the methods section, because MIN(18F) was 60% of the MAX(18F) value in the LV wall. However, the 1 cm insert area is clearly visible in 18F and R-82 PET images (Fig. 4) and their corresponding circumferential profiles (Fig. 6). On the contrary, in the 99mTc/18F SPECT study, the 1 cm insert was not clearly visible in the reconstructed images (Fig. 3) and circumferential profiles (Fig. 5).

Discussion

The results show that PET study provides images of better resolution and sensitivity than SPECT study. This results in better contrast for cold lesions created by the inserts and better determination of viability/nonviability using standard criteria. The differences in resolution and sensitivity between PET and SPECT studies are significant. The difference in sensitivity between the PET 18F study vs. the SPECT 18F study is a factor of 2.5. The difference in resolution is less pronounced, but sill present. For 18F SPECT the FWHM = 5.3 mm, while for 18F PET FWHM = 4.44 ± 0.04 mm in the tangential direction and FWHM = 4.85 ± 0.08 mm in the radial direction. These differences in resolution and sensitivity results in significantly better PET images comparing with the SPECT images in the study (Fig. 3, 4, 5, Fig. 6).

Using commonly applied criteria [13-24], SPECT failed for all three inserts to provide the accurate diagnosis of nonviability, which is significant drawback. While 1 cm lesion may not be clinically important, as discussed below, failure to properly classify 2 cm and 3 cm lesions may be a problem for wider 18F SPECT clinical application. On the other hand, PET correctly diagnosed 2 cm and 3 cm lesions as nonviable and failed only for 1 cm insert to provide accurate diagnosis because MIN(18F) was 60% of the MAX(18F) value in the LV wall. One way to improve PET diagnostics accuracy is to raise the threshold from 50% to 60% for our PET system. But, 1 cm lesion is not of clinical importance because question of viability usually apply to large segment or multisegment region. However, in the PET study 1 cm insert was clearly visible in both the 18F and 82Rb images, while in the 99mTc/18F SPECT study a 1 cm insert was not clearly visible in the images and circumferential profiles (Fig.3, 4, 5, Fig. 6).

In addition, an important difference between the SPECT and PET images of the phantom was that 18F SPECT images were of inferior quality compared with SPECT 99mTc images, while 18F PET images were better in quality than corresponding 82Rb PET images. Consequently, for SPECT, the defects were seen as mismatches, while in PET they tended to be seen as reverse mismatches.

The reason for this is that the gamma camera was optimized for 99mTc 140 keV photon imaging. Resolution properties for 18F imaging are better on the PET system than on the gamma camera. Septal penetration is also a significant problem in gamma camera 18F imaging. In our high count phantom studies sensitivity was not the main issue, but in a clinical situation that can also be a problem for standard gamma cameras. For a 0.9525 cm (3/8") thick NaI(Tl) crystal 73% of 18F 511 keV photons do not interact, 15% interact through Compton scatter and only 12% through the photoelectric effect, which is the mode most desirable for good detection. This means that for 18F 511 keV photons, standard gamma cameras have very poor sensitivity. Doubling the thickness of the NaI(Tl) crystal to 1.905 cm (3/4") will increase the number of photoelectric interactions to 26%, Compton scatter to 20%, and will decrease the number of noninteracting photons to 54%. But, still this represents relatively poor sensitivity, especially when compared with 99mTc 140 keV photons interacting with a 0.9525 cm (3/8") thick NaI(Tl) crystal: 88% photoelectric effect, 2% Compton scatter and only 10 % no interaction.

82Rb PET images have poorer resolution and contrast when compared with 18F images due to a higher 82Rb positron maximum energy of 3.35 MeV (emitted 83% of the time) and 2.57 MeV (emitted 12% of the time). In comparison, 18F positron maximum energy is only 0.64 MeV. Higher positron energy results in higher average distance positron travel in medium prior to annihilation, 2.40 mm for 82Rb vs. 0.35 mm for 18F.

This study examined the effect of system resolution on the classification of small intramural defects as "viable" or "nonviable" by commonly used criteria [13-24]. Over the last two decades, a variety of criteria have been used to define viability, few of which are exactly the same. Nevertheless, the criteria used here are some of the most commonly used. Use of alternate criteria, i.e., 60% threshold [22,23], or other arbitrary or empirical criteria would result in similar, if not identical, conclusions. In practice, questions of viability usually apply to large segmental and multisegmental regions of dysfunction, hypoperfusion and hypometabolism [13-24], since small perfusion (function) defects have little impact on LV functional properties. Small defects of 2 cm or less would not be considered clinically for questions of viability. However, perceived false mismatches at the edges of defects several cm in extent may result in misclassification of significant portions of the myocardium as viable in SPECT studies, as would modest defects of 2–4 cm. To a lesser extent, false negatives of viability may occur in 82Rb/18F PET studies.

A similar phantom comparison between SPECT and a dedicated PET system [1] concluded that by using an appropriate threshold to define a defect, SPECT can accurately measure defect size similarly to the manner of PET. Also, the same group recently published the results of their clinical comparison of SPECT with PET in the assessment of myocardial viability [4], and concluded that SPECT provided similar information to that of PET and MRI. The phantom used was very similar to our phantom, the PET system was the same and, as in our study, motion and background effects were not taken onto account. These studies recognize already mentioned advantages of PET over SPECT, which has higher spatial resolution, higher count sensitivity and routine use of attenuation and scatter correction in PET, but not in SPECT. However, the difference in the UHE collimator design and properties, the difference in the gamma camera crystal thickens, our 0.9525 cm (3/8") vs. 1.6 cm (5/8") thick NaI(Tl) crystal in these studies [1,4], a difference in acquisition (360 degree in our studies vs. 180 degree in these studies) and a difference in evaluation of SPECT and PET data lead us to a slightly different conclusion.

Conclusion

The results of this phantom study suggest that for smaller defects, the 99mTc/18F SPECT imaging cannot entirely replace the more expensive 82Rb/18F PET for myocardial perfusion/viability imaging, due to poorer image spatial resolution and poorer defect contrast.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

Both authors, KK and JM, have made substantial contributions in acquisition, processing and analysing of data, and writing the manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Karin Knešaurek, Email: karin.knesaurek@mssm.edu.

Josef Machac, Email: josef.machac@mssm.edu.

References

- Matsunari I, Yoneyama T, Kanayama S, Matsudaira M, Nakajima K, Taki J, Nekolla SG, Tonami N, Hisada K. Phantom Studies for Estimation of Defect Size on Cardiac 18F SPECT and PET: Implications for Myocardial Viability Assessment. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:1579–1585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JA, Sandler MP, Ohana I, Weinfeld Z. High-energy (511 keV) imaging with the scintillation camera. Radiographics. 1996;16:1183–1194. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.16.5.8888397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler MP, Bax JJ, Patton JA, Visser FC, Martin WH, Wijns W. Fluorine-18-florodeoxyglucosecardiac imaging using a modified scintillation camera. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:2035–2043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunari I, Kanayama S, Yoneyama T, Matsudaira M, Nakajima K, Taki J, Nekolla SG, Tonami N, Hisada K. Electrocardiographic-gated dual-isotope simultaneous acquisition SPECT using 18F-FDG and 99mTC-sestamibi to assess myocardial viability and function in a single study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:195–202. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1668-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knešaurek K, Machac J. Improvement of the flourine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose images in simultaneous F-18 FDG/Tc-99m collimated SPECT imaging. Med Phys. 1999;26:917–923. doi: 10.1118/1.598483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullani NA, Goldstein RA, Gould KL, Marani SK, Fisher DJ, O'Brien HA, Jr, Loberg MD. Myocardial perfusion with rubidium-82. I. Measurement of extraction fraction and flow with external detectors. J Nucl Med. 1983;24:898–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RA, Mullani NA, Marani SK, Fisher DJ, Gould KL, O'Brien HA., Jr Myocardial perfusion with rubidium-82. II. Effects of metabolic and pharmacologic interventions. J Nucl Med. 1983;24:907–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RA, Mullani NA, Wong WH, Hartz RK, Hicks CH, Fuentes F, Smalling RW, Gould KL. Positron imaging of myocardial infarction with rubidium-82. J Nucl Med. 1986;27:1824–1829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, Mullani N, Gould KL. Coronary flow and flow reserve by PET simplified for clinical applications using rubidium-82 or nitrogen-13-ammonia. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1701–1712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JW, Robert R, Sciacca RR, Chou R-L, Laine AF, Bergmann SR. Quantification of Myocardial Perfusion in Human Subjects Using 82Rb and Wavelet-Based Noise Reduction. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:201–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knešaurek K, Machac J. Three-window transformation cross-talk correction for simultaneous dual-isotope imaging. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:1992–1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom M, Eriksson L, Bohm C, Blomqvist G, Litton J. Correction for scatter radiation in a ring detector positron camera by integral transformation of the projections. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1983;10:845–850. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198302000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould KL, Yoshida K, Hess MJ, Haynie M, Mullani N, Smalling RW. Myocardial metabolism of fluorodeoxyglucose compared to cell membrane integrity for the potassium analogue rubidium-82 for assessing infarct size in man by PET. J Nucl Med. 1991;32:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas F, Haehnel CJ, Picker W, Nekolla S, Martinoff S, Meisner H, Schwaiger M. Preoperative positron emission tomographic viability assessment and perioperative and postoperative risk in patients with advanced ischemic heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1693–1700. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00375-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoder H, Campisi R, Ohtake T, Hoh CK, Moon DH, Czernin J, Schelbert HR. Blood flow-metabolism imaging with positron emission tomography in patients with diabetes mellitus for the assessment of reversible left ventricular contractile dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1328–1337. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sand NP, Bottcher M, Madsen MM, Nielsen TT, Rehling M. Evaluation of regional myocardial perfusion in patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction: comparison of 13N-ammonia PET and 99mTc sestamibi SPECT. J Nucl Cardiol. 1998;5:4–13. doi: 10.1016/S1071-3581(98)80004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beanlands RS, Hendry PJ, Masters RG, deKemp RA, Woodend K, Ruddy TD. Delay in revascularization is associated with increased mortality rate in patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction and viable myocardium on fluorine 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging. Circulation. 1998;98:II51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrighi JA, Ng CK, Dey HM, Wackers FJ, Soufer R. Effect of left ventricular function on the assessment of myocardial viability by technectium-99m sestamibi and correlation with positron emission tomography in patients with healed myocardial infarcts or stable angina pectoris, or both. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:1007–1013. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(97)00594-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunning MG, Anagnostopoulos C, Knight CJ, Pepper J, Burman ED, Davies G, Fox KM, Pennell DJ, Ell PJ, Underwood SR. Comparison of 201Tl, 99mTc-tetrofosmin, and dobutamine magnetic resonance imaging for identifying hibernating myocardium. Circulation. 1998;98:1869–1874. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.18.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huitink JM, Visser FC, Bax JJ, van Lingen A, Groenveld AB, Teule GJ, Visser CA. Predictive value of planar 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose imaging for cardiac events in patients after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:1072–1077. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(98)00143-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine MG, McGill CC, Ahlberg AW, White MP, Giri S, Shareef B, Waters D, Heller GV. Functional assessment with electrocardiographic gated single-photon emission computed tomography improves the ability of technetium-99m sestamibi myocardial perfusion imaging to predict myocardial viability in patients undergoing revascularization. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:1–5. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(98)00772-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoufis E, McGhie AI. Radionuclide techniques for the assessment of myocardial viability. Tex Heart Inst J. 1998;25:272–279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melon PG, de Landsheere CM, Degueldre C, Peters JL, Kulbertus HE, Pierard LA. Relation between contractile reserve and positron emission tomographic patterns of perfusion and glucose utilization in chronic ischemic left ventricular dysfunction: implications for identification of myocardial viability. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1651–1659. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00373-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebelink HM, Blanksma PK, Crijns HJ, Bax JJ, van Boven AJ, Kingma T, Piers DA, Pruim J, Jager PL, Vaalburg W, van der Wall EE. No difference in cardiac event-free survival between positron emission tomography-guided and single-photon emission computed tomography-guided patient management: a prospective, randomized comparison of patients with suspicion of jeopardized myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:81–88. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)01087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]