Abstract

Understanding external deciding factors in growth and morphology of reef corals is essential to elucidate the role of corals in marine ecosystems, and to explain their susceptibility to pollution and global climate change. Here, we extend on a previously presented model for simulating the growth and form of a branching coral and we compare the simulated morphologies to three-dimensional (3D) images of the coral species Madracis mirabilis. Simulation experiments and isotope analyses of M. mirabilis skeletons indicate that external gradients of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) determine the morphogenesis of branching, phototrophic corals. In the simulations we use a first principle model of accretive growth based on local interactions between the polyps. The only species-specific information in the model is the average size of a polyp. From flow tank and simulation studies it is known that a relatively large stagnant and diffusion dominated region develops within a branching colony. We have used this information by assuming in our model that growth is entirely driven by a diffusion-limited process, where DIC supply represents the limiting factor. With such model constraints it is possible to generate morphologies that are virtually indistinguishable from the 3D images of the actual colonies.

Keywords: morphogenesis, scleractinian corals, diffusion-limited growth, morphological plasticity, computed tomography scanning, stable isotope analysis

1. Introduction

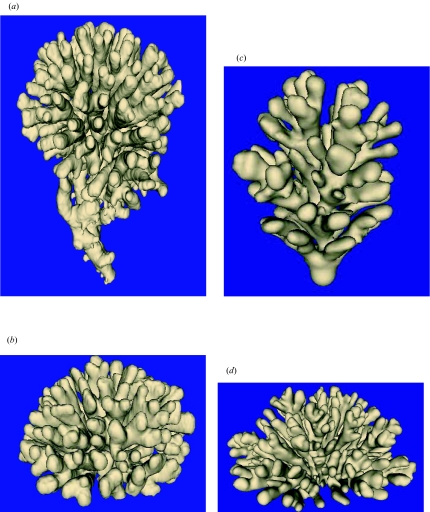

Scleractinian corals are well known for their high morphological plasticity related to environmental forcing in light (Muko et al. 2000) and hydrodynamic (Bruno & Edmunds 1998; Kaandorp 1999) gradients. This externally driven morphological plasticity makes scleractinian corals extremely suitable for studying patterns of morphogenesis, and allows distinguishing intrinsic genetic regulation from external environmental forcings. However, experimental work on growth, colony shape and regeneration of corals is greatly limited by the difficulties experienced in accessing relevant local physical environmental parameters, such as micro-flow patterns, thickness of boundary layers, absorption of food particles (Sebens et al. 1997; Anthony 1999) and dissolved material (Sorokin 1993; Lesser et al. 1994; Marubini & Thake 1999; Marubini et al. 2002). As a case study to model growth and shape of phototrophic corals, we used the symbiont-bearing (zooxanthellate) coral species Madracis mirabilis (figure 1a,b). For zooxanthellate corals, the relevant physical environment consists of a phototrophic component with local calcification related to local light and inorganic carbon concentrations (Lesser et al. 1994; Marubini & Thake 1999; Marubini et al. 2002), and a heterotrophic component with local calcification related to the uptake of nutrients from the environment. Nutrients affecting the heterotrophic component can be either dissolved material (phosphate and nitrate) (Sorokin 1993) or particulate material (Sebens et al. 1997; Anthony 1999). The relative contribution of the phototrophic and heterotrophic components to the calcification can be estimated from skeletal δ13C and δ18O values by applying a model of kinetic versus metabolic isotope fractionation (McConnaughey et al. 1997; Heikoop et al. 2000; Maier et al. 2003).

Figure 1.

Surface-renderings of CT scans of Madracis mirabilis colonies and simulated objects. C indicates the compactness. (a) Upward-growing morphology (C=0.29) and (b) hemispherical morphology (C=0.41) of M. mirabilis. Simulated growth forms: (c) upward-growing morphology (C=0.30) and (d) hemispherical morphology (C=0.24). Animations of all objects shown in figure 1 can be found in electronic Appendix B.

In flume studies it was found that densely packed branching colonies, similar to those of M. mirabilis, act as a solid body (Chamberlain & Graus 1977). In a previous study we have performed simulation studies using actual morphologies of M. mirabilis in a laminar flow regime and found that around the branching morphologies, relatively large diffusive boundary layers are formed, which act as stagnant regions (Kaandorp et al. 2003). Flow starts to circumvent the colony and stagnant—and hence diffusion dominated—regions, even for relatively high flow velocities of up to 20 cm s−1 (Chamberlain & Graus 1977), develop within the colony. Subsequently, photosynthetic bicarbonate assimilation results in depletion and gradients of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) within these boundary layers.

In M. mirabilis we observe a gradual change from more compact high-flow morphologies (for example the colony shown in figure 1a) at shallow locations to more open thin-branching low-flow morphologies at deeper locations (Kaandorp et al. 2003). In the branching coral Pocillopora damicornis, a similar morphological range is observed going from high-flow to low-flow locations (Veron & Pichon 1976). In Lesser et al. (1994) it was demonstrated that the morphological plasticity in P. damicornis provides a mechanism to minimize the diffusional boundary layer thickness and maximize mass transfer through the boundary layer under different flow regimes. In the compact high-flow morphology relatively smaller boundary layers develop, whereas in the open low-flow morphology, relatively larger boundary layers are formed. In both morphologies, under high-flow and low-flow conditions, respectively, sufficient transfer of nutrients through the boundary layer for the development of the colony is possible.

First, we have verified the assumption that calcification of M. mirabilis is mainly supported by photosynthesis through analysis of the δ13C and δ18O isotopes of the skeletons shown in figure 1a,b (Maier et al. 2003). If photosynthesis is the main source of energy then DIC gradients will play a crucial role in the morphogenesis of M. mirabilis. From growth models from physics (e.g. Brener et al. 1992) it is known that gradients of a growth-limiting agent may induce branching patterns in abiotic growth processes. Our hypothesis is that gradients of a limiting nutrient (DIC) are required to induce a branching growth pattern in the development of coral colonies such as M. mirabilis. An alternative hypothesis is that the growth is mainly limited by local light intensities. Previous simulation studies (Graus & Macintyre 1982; Kaandorp & Kübler 2001) demonstrate that light-intensity-limited growth yields very different morphologies (for example spherical, column or plate-like morphologies), which may approximate the colony morphology of other coral species (for example, Montastrea annularis).

We have obtained actual morphologies of M. mirabilis (figure 1a,b) with computed tomography (CT) scanning techniques. This allows us to make a visual and quantitative comparison between the actual morphologies and the simulated growth forms. The goal is to construct a generative simulation model based on a minimal set of parameters and assumptions. With this model we want to simulate the full morphogenesis of the coral in space and time and compare the simulated results to actual three-dimensional (3D) morphological data. The purpose is to come to a ‘minimal’ model which has the highest explanatory and predictive power. We use a morphological simulation model, the accretive growth model, in combination with a diffusion model, to study the hypothesis that external gradients of inorganic carbon in the boundary layers of the colony are shaping the coral.

We have used a hydrodynamical model, based on the lattice Boltzmann method, that is suitable for computing flow patterns in complex-shaped 3D morphologies (Kaandorp et al. 2003). The method can be used in conjunction with a method to study the dispersion of a tracer through diffusion. Based on the findings in experimental work in flume studies (Chamberlain & Graus 1977) and previous simulation studies using actual M. mirabilis morphologies (Kaandorp et al. 2003), we have investigated the hypothesis that a diffusion-dominated model is sufficient to approximate the influence of external gradients of DIC on the growth process.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 The computed tomography scans

The M. mirabilis colonies were collected at depths between 6 m and 20 m at the reef of Curaçao (Netherlands Antilles, 12° N, 69° W). 3D images of the colonies were obtained using X-ray CT scanning techniques (Kaandorp & Kübler 2001). The CT scan data were stored in digital imaging and communications in medicine (DICOM) format (a general data format used for medical images). The CT scan data consist of 512×512×z (20≤z≤50) 3D pixels, the so-called ‘voxels’. The slice thickness of the CT scan data is 2.5 mm in the xy direction. Each voxel represents a density value between 0 and 212, where 0 is the lowest density (the air around the coral skeleton), while high values indicate the calcium carbonate of the coral skeleton. In figure 1a,b, the 3D images are visualized using a surface rendering technique. The surface is constructed, approximately, at the boundary between the air and the calcium carbonate skeleton of the coral. With this technique, using the original dataset of 512×512×z voxels, an image is reconstructed with an equal resolution in x, y and z directions (for details see Schroeder et al. 1997). Only the surface of the coral is visualized, without any surface structures such as corallites. On the voxels representing the surface of the corals a triangulated mesh was constructed using the marching cubes method (Lorensen & Cline 1987).

2.2 Calculation of photosynthesis to respiration ratio

We calculated the average photosynthesis to respiration (P/R) values using carbon (δ13C) and oxygen (δ18O) stable isotope data from carbonate samples (Maier et al. 2003) derived from the skeleton surface of the M. mirabilis colonies shown in figure 1a,b (n=36 and n=78, respectively), tissue δ13C samples (separated zooxanthellae and animal polyp, n=43 each) of additional M. mirabilis colonies sampled between 5 m and 20 m depth, and δ18O and δ13C of sea water (seawater samples were taken in biweekly intervals between mid-April and the end of June 2001 at depths of 5 m, 15 m, 25 m and 40 m, n=36). This dataset allowed us to calculate average P/R values for the M. mirabilis colonies based on the approaches described in McConnaughey et al. (1997) and Heikoop et al. (2000). We adjusted the equations for calculation of P/R values from stable isotope data as follows:

| (2.1) |

| (2.2) |

The parameters used in equations (2.1) and (2.2) are summarized in table 1.

Table 1.

Description of the parameters used in equations (2.1) and (2.2) for the calculation of the P/R ratio.

| parameter | description |

| Moffset | metabolic offset from kinetic line |

| δ13Corig | measured δ13C of same skeletal sample as δ18Oorig |

| δ13Oorig | measured δ18O of same skeletal sample as δ13Corig |

| a | slope of relation of δ13C to δ18O for kinetic isotope fractionation. We used a slope of three which is a rather conservative estimate for establishing P/R ratios. |

| δ18Oeq | average δ18O value for δ18O of aragonite in equilibrium with sea water, with an average of δ18Oeq of 0.32±0.04 s.e. |

| δ13Ceq | average δ13C value for aragonite in equilibrium with sea water, with δ13Ceq=δ13CDIC+2.7 (Heikoop et al. 2000). The average δ13CDIC was 1.32±0.02 s.e. and we thus used a δ13Ceq of 4.0 |

| r | offset of δ13C from kinetic line as a result of coral respiration, which is estimated to be −1.5 (McConnaughey et al. 1997; Heikoop et al. 2000) |

| δ13Cz/δ13Cp | δ13C of zooxanthellae/δ13C of animal polyp from paired samples with an average value of 0.989±0.003 |

There was no difference between depth effect on seawater δ13C or δ18O and consequently all data were put together and the average value was used to estimate the equilibrium values for aragonite in seawater. The samples of separated animal polyp and zooxanthellae tissues of M. mirabilis colonies for tissue δ13C analyses were retrieved from depths between 5 m and 20 m in June 2002 (C. Maier, unpublished data).

2.3 Modelling diffusion

We used a cellular-automata-based particle model, the ‘moment propagation’ method (Lowe & Frenkel 1995; Merks et al. 2002) in conjunction with the lattice Boltzmann method (Chopard & Droz 1998; Succi 2001) to model the dispersion of nutrients in the external environment by diffusion. The lattice Boltzmann method is especially suitable for developing scalable simulations (using distributed computation) of advection–diffusion/diffusion processes and modelling boundary layers in complex 3D geometries (Kaandorp et al. 1996; Koponen et al. 1998; Kandhai et al. 2002). Simulation of the diffusion process represents the computational bottleneck. Typical run-times of the simulations shown in this paper are 30 h on a parallel machine consisting of 16 processors of 700 MHz each. Details on the equations and parameters used in the lattice Boltzmann simulations and the diffusion model are provided in Appendix A.

2.4 The accretive growth model

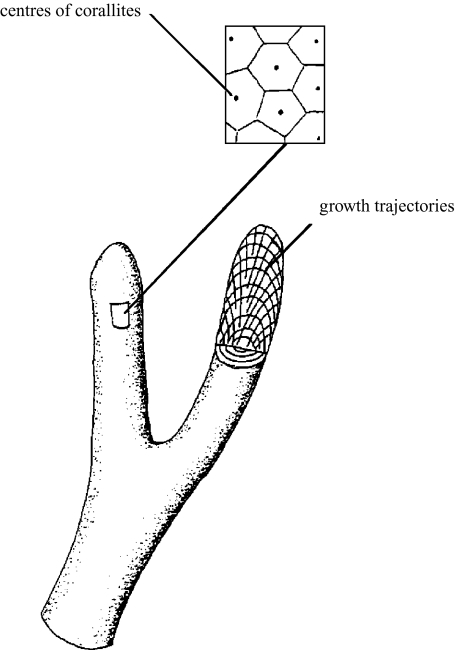

For our simulations we used the polyp oriented accretive growth model (Merks et al. 2004), which derives from differential accretive growth models (Kaandorp & Kübler 2001; Kaandorp & Sloot 2001; Merks et al. 2003). The growth process is modelled as a surface-normal deposition process, where new material is deposited along the normal vectors that are constructed on the surface of the previous growth stage (figure 2). X-ray studies demonstrated that the coral polyp tends to be set normal with respect to the previous growth layers (Darke & Barnes 1993; Le Tissier et al. 1994). The polyp moves outward with the (living) periphery and leaves a growth trajectory which can be reconstructed by connecting the positions of the centre of a corallite in the successive growth layers. For the simulation model it is therefore assumed that the living tissue deposits new layers of material (aragonite, in the real coral) on top of the previous layers, which remain unchanged. The polyp is carried upwards, vacating the lower skeletal regions. In the real coral, the vacated skeletal regions are separated from the living polyp by dissepiments. This mode of deposition represents an additive-growth pattern of the individual polyps.

Figure 2.

Diagram of the accretive-growth process. Part of the surface is enlarged (see inset), showing the polygons tessellating the surface and the position of the corallites. Part of one branch is removed to show the growth layers and the trajectories of the corallites.

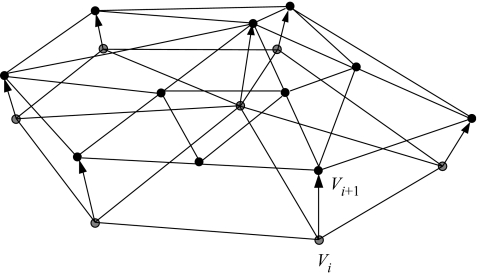

In the model, the growth layers are represented by layers of triangles. A small detail of the model is shown in figure 3, where a new layer of triangles (layer i+1 with vertices Vi+1) is constructed on top of the previous layer (layer i with vertices Vi). We based the simulation model on the hypothesis that DIC used by photosynthesis is the main limiting factor in the calcification process, and growth is limited by the local amount of nutrient available to the simulated polyp. Light was not considered to be limiting for photosynthesis or coral growth. We assume that inorganic carbon in the immediate environment is exclusively distributed by diffusion. The nutrient distribution was simulated using the diffusion model described above (see Appendix A for details). The diffusion model was coupled to the accretive-growth model, by mapping the geometric representation (the layers of triangles) onto a lattice of 2003 nodes. The lattice representation was used for computing the gradients around the simulated growth form. In the diffusion simulations it was assumed that the vertices shown in figure 3 represent the anchor points of the polyps to the skeleton, from which the simulated polyps project along the normal vector. Thus the nutrients are absorbed at a small distance from the simulated coral surface, representing the height of the coral polyps, while the source nodes are located at a certain distance from the object. After the gradients have been computed, the normalized flux of nutrients ci into the polyp can be calculated. The linear extension rate of the simulated skeleton is driven by the amount of absorbed simulated nutrients. The thickness of a new layer li+1, the distance between two successive vertices Vi and Vi+1, is computed by using the growth function

| (2.3) |

where is the average normal vector in vertex Vi, ci is the amount of absorbed simulated nutrients in vertex Vi, and s is the maximal thickness of the growth layer. In this growth function we assume a linear relationship between the local amount of deposited material and the local amount of absorbed nutrient from the environment.

Figure 3.

Small detail of the accretive-growth model showing the construction of a new layer (layer i+1) on top of the previous layer (layer i). The thickness li+1 of the new layer, the distance between the vertices Vi and Vi+1, is determined by the growth function in equation (2.3).

In the simulations, the polyps interact locally through the simulated fluid and are closely packed on a growth layer. The distance between the simulated polyp varies around a certain (species-specific) mean size of the polyp. Simulated polyps that become too large split up into new ones, while small ones are deleted. In the figure some triangles in the previous layer i have split up into smaller ones during the construction in layer i+1. For further details about the splitting up and deletion of triangles, we refer to aprevious paper on the accretive growth model (Merks et al. 2003). After each growth step, where a new layer of triangles is constructed on top of the previous one, we again compute the gradients. We applied 80 growth steps for the simulations in this paper. In the simulated objects shown in this paper we have taken two representative objects of the polyp oriented model; a complete description of simulated growth forms for various polyp distances can be found in Merks et al. (2004). The size of the simulated growth form and the number of steps are limited by the dimensions of the simulation box (2003 nodes). The simulation is initialized with a small spherical triangulated object.

The simulated and actual morphologies were quantitatively compared by computing the compactness, C, of the objects (Merks et al. 2003). C is defined as the ratio

| (2.3) |

of the volume of the object (Vobject) and the volume of its convex hull (Vhull).

3. Results

We calculated P/R ratios of 3.74±0.11 (± s.e.) and 2.54±0.08 for the M. mirabilis colonies shown in figure 1a,b, respectively. This shows that one of our main assumptions in the simulation model, that the metabolism in M. mirabilis is mainly supported by photosynthesis, is correct.

Figure 1a,b shows the reconstructed surfaces of the M. mirabilis colonies. C was computed using equation (2.4) for both colonies. For the upward-growing morphology in figure 1a, C equals 0.29, whereas in the hemispherical morphology in figure 1b, C equals 0.41.

In figure 1c,d we show examples of simulated morphologies. In figure 1c the source of nutrients is located at the top plane and it is assumed that both the simulated polyps and the ground plane absorb nutrients. An absorbing ground plane represents a hard substrate encrusted with absorbing sessile organisms. The hemispherical shape in figure 1d is generated by assuming that only the simulated polyps absorb nutrients. C equals 0.30 in the upward-growing morphology shown in figure 1c and is 0.24 in the hemispherical morphology (figure 1d). A complete description of the simulated growth forms for various polyp distances, boundary conditions, and alternative growth functions is given in Merks et al. (2004).

4. Discussion

The only species-specific information included in our model is the distance between the polyps and the height of a polyp. Our main discovery is that with the incorporation of simple local rules, controlling the size of individual simulated polyps in the polyp-oriented model (Merks et al. 2004), and local gradients it is possible to generate branching morphologies which approximate closely the morphologies of surface renderings of CT scans of M. mirabilis shown in figure 1a,b. In the simulations we obtained Madracis-like growth forms de novo. Although we did not extensively test the initial conditions in the model, we expect that the model is not very sensitive for the initial conditions in the simulations. We used a spherical object to initialize the growth simulations. After several growth steps, the shape of the initial object hardly influences the shape of the simulated growth form. Another obvious choice for the initial object could, for example, be a sheet of material. A diffusion-limited environment is sufficient to get the correct gradients in the simulated morphogenesis. When comparing simulated and actual objects in figure 1 we see that the branch spacing, which is quite regular and characteristic in M. mirabilis (Sebens et al. 1997), is also very regular in both simulated objects. The compactness, C (equation (2.4)), of the simulated objects shown in figure 1 is close to the C values of the actual objects. The results in figure 1c,d indicate that the model can be used to approximate a branching coral with relatively large closely packed and undifferentiated corallites (e.g. M. mirabilis). By slightly modifying the boundary conditions, using an absorbing substrate plane (figure 1c) in the upward-growing morphology (figure 1c) and a non-absorbing substrate plane in the hemispherical shape (figure 1d), it is possible to simulate morphologies of M. mirabilis as shown in figure 1a,b. The upward-growing morphology in M. mirabilis is typically found under circumstances when the colony is competing for space and resources with neighbouring colonies, while the hemispherical morphology develops in isolated colonies. The competition effect was represented in the simulation by an absorbing substrate plane.

Intricately branched corals appear to be more susceptible to mortality than massive corals when bleaching occurs during periods of high sea-surface temperatures (Davies et al. 1997; Nakamura & Van Woesik 2001; Kaandorp et al. 2003; Nakamura et al. 2003). One hypothesis is that in intricately branched corals mass transfer through the boundary layer is strongly diffusion-dominated and can disperse fewer of the metabolic by-products that arise during warmer periods (Nakamura & Van Woesik 2001; Nakamura et al. 2003). Our results confirm the central role of diffusion-dominated boundary layers, and demonstrate the influence of (external) driving factors in coral functioning and coral growth. Although we have limited our model exclusively to the diffusion-dominated regime, it can be expected that advection still plays an important role in the formation of gradients and boundary layers. For this reason we think it is important to use an advection–diffusion model in combination with a morphogenetic model of the coral. Our results indicate that nutrient gradients may play a major role in the morphogenesis of branching marine sessile organisms with an accretive growth process in general. A similar model can be applied in other scleractinian corals and sponges (Abraham 2001; Kaandorp & Kübler 2001) with a nutrient-limited accretive growth process. In several other cases, for example in the sceleractinian coral Montastrea annularis (Graus & Macintyre 1982), the local available light intensity is the major parameter controlling accretive growth. Furthermore it may be hypothesized that in some sessile organisms with accretive growth, the final shape of the organism is controlled by a mixture of parameters (nutrient gradients, local light intensity and hydrodynamics). For a better understanding of growth and form in a morphological highly diverse coral genus like Acropora or the diversity within the Madracis genus, the influence of genetic factors (Van Oppen et al. 2001) and zooxanthellae (Little et al. 2004) have to be included in a more detailed morphogenetic model and be compared with actual genetic and morphological data.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. E. H. Lampmann for his help and advice in obtaining CT scans of the corals; R. G. Belleman and A. Wiegersma for their help with the visualization; A. G. Hoekstra for his advice during the development of the simulations; M. Segl for stable isotope analyses of skeleton and seawater; and S. Schouten for providing the facilities to analyse tissue stable-isotopes. This project was initiated during the ‘modelling growth and form of marine sessile organisms’ workshop in 1999, funded by the National Science Foundation at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis in Santa Barbara, CA.

Appendix A: The Lattice Boltzmann and Moment Propagation Method

The general form of the lattice Boltzmann equation is

| (A 1) |

where fi is the concentration of particles that travels with velocity . With the discrete velocity, , the particle distributions travel to the next lattice node in one time step, Δt. The collision operator, Ωi, differs for the many lattice Boltzmann methods. In the lattice Boltzmann Bhatnagher–Gross–Krook method (Qian et al. 1992) that we use, the particle distribution after propagation is relaxed towards the equilibrium distribution as

| (A 2) |

The relaxation τ parameter determines the kinematic viscosity, υ, of the simulated fluid, according to,

| (A 3) |

which was set to υ=1/6 for the simulations shown in this paper.

The equilibrium distribution is a function of the local density, ρ, and the local velocity, . These are the first-and second-order moments of the particle distribution given by

| (A 4) |

and

| (A 5) |

The equilibrium density is calculated from

| (A 6) |

in which cs is the speed of sound, the index and tp is the corresponding equilibrium density for . For the 3D, 19 velocity lattice (D3Q19) that we have used in our simulations, t0=1/3 (rest particle), t1=1/18 (particles streaming to the face-connected neighbours) and t2=1/36 (particles streaming to the edge-connected neighbours).

As soon as a steady flow pattern has been obtained with the lattice Boltzmann method, the advection and diffusion of nutrients through the fluid is simulated using the moment propagation method (Lowe & Frenkel 1995; Merks et al. 2002). The moment propagation method solves the advection–diffusion equation to second order (Warren 1997). A scalar quantity, P, is distributed over the neighbouring lattice nodes, according to the probability, fi/ρ, that a fluid particle moves with velocity, , after collision,

| (A 7) |

where the whole quantity inside [...] is evaluated at , and Δ is the fraction of resting tracer particles, by which the diffusion coefficient can be set as (Warren 1997; Merks et al. 2002)

| (A 8) |

In this paper D was set to the value 1/6 and was set to 0, the diffusion-limited regime.

References

- Abraham E.R. The fractal branching of an arborescent sponge. Mar. Biol. 2001;138:503–510. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony K.R.N. Coral suspension feeding on fine particulate matter. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1999;232:85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Brener E., Kassner K., Műller-Krumbhaar H. Pattern formation in first-order phase transistions. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C. 1992;3:825–851. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno J.F., Edmunds P.J. Metabolic consequences of phenotypic plasticity in the coral Madracis mirabilis (Duchassaing and Michelotti): the effect of morphology and water flow on aggregate respiration. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1998;229:187–195. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain J.A., Graus R.R. Water flow and hydromechanical adaptations of branched reef corals. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1977;25:112–125. [Google Scholar]

- Chopard B., Droz M. Cellular automata modeling of physical systems. Cambridge Univerity Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Darke W.M., Barnes D.J. Growth trajectories of corallites and ages of polyps in massive colonies of reef-building corals of the genus. Porites. Mar. Biol. 1993;117:321–326. [Google Scholar]

- Davies J.M., Dunne R.P., Brown B.E. Coral bleaching and elevated sea-water temperature in Milne Bay Province Papua New Guinea 1996. Mar. Freshwat. Res. 1997;48:513–518. [Google Scholar]

- Graus R.R., Macintyre I.G. Variation in growth forms of the reef coral Montastrea annularis (Ellis and Solander): a quantitative evaluation of growth response to light distribution using computer simulation. Smitson. Contr. Mar. Sci. 1982;12:441–464. [Google Scholar]

- Heikoop J.M., Dunn J.J., Risk M.J., Schwarcz H.P., McConnaughey T.A., Sandeman I.M. Separation of kinetic and metabolic isotopic effects in carbon-13 records preserved in reef coral skeletons. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2000;64:975–987. [Google Scholar]

- Kaandorp J.A. Morphological analysis of growth forms of branching marine sessile organisms along environmental gradients. Mar. Biol. 1999;134:295–306. [Google Scholar]

- Kaandorp J.A., Kübler J.E. The algorithmic beauty of seaweeds, sponges and corals. Springer; Heidelberg, Germany: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kaandorp J.A., Sloot P.M.A. Morphological models of radiate accretive growth and the influence of hydro dynamics. J. Theor. Biol. 2001;209:257–274. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2001.2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaandorp J.A., Lowe C.P., Frenkel D., Sloot P.M.A. The effect of nutrient diffusion and flow on coral morphology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;77:2328–2331. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaandorp J.A., Koopman E.A., Sloot P.M.A., Bak R.P.M., Vermeij M.J.A., Lampmann L.E.H. Simulation and analysis of flow patterns around the scleractinian coral Madracis mirabilis (Duchassaing and Michelotti) Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2003;358:1551–1557. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2003.1339. doi:10.1098/rstb.2003.1339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandhai D., Hlushkou D., Hoekstra A.G., Sloot P.M.A., Van As H., Tallarek U. Influence of stagnant zones on transient and asymptotic dispersion in macroscopically homogeneous porous media. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002;88:234501–234504. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.234501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koponen A., Kandhai D., Hellen E., Alava M., Hoekstra A., Kataja M., Niskanen K., Sloot P.M.A., Timmonen J. Permeability of three-dimensional random fiber webs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998;80:716–719. [Google Scholar]

- Le Tissier M. D’ A. A., Clayton B., Brown B.E., Spencer Davies P. Skeletal correlates of coral density banding and an evaluation of radiography as used in scelerochronology. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1994;110:29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lesser M.P., Weis V.M., Patterson M.R., Jokiel P.L. Effects of morphology and water motion on carbon delivery and productivity in the reef coral, Pocillopora damicornis (Linnaeus): diffusion barriers, inorganic carbon limitation, and biochemical plasticity. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1994;178:153–179. [Google Scholar]

- Little A.F., Van Oppen M.J.H., Willis B.L. Flexibility in algal endosymbioses shapes growth in reef corals. Science. 2004;304:1492–1494. doi: 10.1126/science.1095733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorensen W.E., Cline H.E. Marching cubes: a high resolution 3D surface construction algorithm. ACM Comput. Graphics. 1987;21:163–169. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe C.P., Frenkel D. The super long-time decay of velocity fluctuations in a two-dimensional fluid. Physica A. 1995;220:251–260. [Google Scholar]

- McConnaughey T.A., Burdett J., Whelan J.F., Paul C.K. Carbon isotopes in biological carbonates: respiration and photosynthesis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1997;61:611–622. [Google Scholar]

- Maier C., Pätzold J., Bak R.P.M. The skeletal isotopic composition as an indicator of ecological plasticity in the coral genus Madracis. Coral Reefs. 2003;22:370–380. [Google Scholar]

- Marubini F., Thake B. Bicarbonate addition promotes coral growth. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1999;44:716–720. [Google Scholar]

- Marubini F., Ferrier-Pages C., Cuif J. Suppression of skeletal growth in scleractinian corals by decreasing ambient carbonate-ion concentration: a cross-family comparison. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2002;270:179–184. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2212. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merks R.M.H., Hoekstra A.G., Sloot P.M.A. The moment propagation method for advection-diffusion in the lattice Boltzmann method: validation and Peclet number limits. J. Comput. Phys. 2002;183:563–576. [Google Scholar]

- Merks R.M.H., Hoekstra A.G., Kaandorp J.A., Sloot P.M.A. Models of coral growth: spontaneous branching, compactification and the Laplacian growth assumption. J. Theor. Biol. 2003;224:153–166. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(03)00140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merks R.M.H., Hoekstra A.G., Kaandorp J.A., Sloot P.M.A. Polyp oriented modelling of coral growth. J. Theor. Biol. 2004;228:559–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muko S., Kawasaki K., Sakai K., Takasu F., Shigesada N. Morphological plasticity in the coral Porites sillimaniani and its adaptive significance. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2000;66:225–239. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T., Van Woesik R. Water-flow rates and passive diffusion partially explain differential survival of corals during the 1998 bleaching event. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2001;212:301–304. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T., Yamasaki H., Van Woesik R. Water flow facilitates recovery from bleaching in the coral Stylophora pistillata. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2003;256:287–291. [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y.H., D’Humieres D., Lallemand P. Lattice BGK models for the Navier-Stokes equation. Euorophys Lett. 1992;17:479–484. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder W., Martin K., Lorensen B. The visualization toolkit: an object-oriented approach to 3D graphics. 2nd edn. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sebens K.P., Witting J., Helmuth B. Effects of water flow and branch spacing on particle capture by the reef coral Madracis mirabilis (Duchassaing and Michelotti) J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1997;211:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sorokin Y.I. Coral reef ecology. Springer; Heidelberg, Germany: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Succi S. The lattice Boltzmann equation: for fluid dynamics and beyond. Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oppen M.J.H., McDonald B.J., Willis B.L., Miller D.J. The evolutionary history of the coral genus Acropora (Scleractinia, Cnidaria) based on mitochondrial and a nuclear marker: reticulation, incomplete lineage sorting, or morphological convergence? Mol. Biol. Evol. 2001;18:1315–1329. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veron J.E.N., Pichon M. Scleractinia of Eastern Australia. Part V. Family Acroporidae. Australian Government Publishing Service; Canberra, Australia: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Warren P.B. Electroviscous transport problems via lattice-Boltzmann. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C. 1997;8:889–898. [Google Scholar]