Abstract

In an established Candida albicans murine keratitis model, combination therapy with ophthalmic preparations of fluconazole and cyclosporine A (CsA) demonstrated in vivo drug synergy and effectively resolved wild-type C. albicans infection more rapidly than monotherapy with either drug. Calcineurin, the target of CsA, was also found to contribute to pathogenicity.

Fungal infections of the cornea (fungal keratitis or keratomycosis) cause significant morbidity and can progress to endophthalmitis, with subsequent risk for visual loss (6). In temperate climates, Candida albicans is the most frequent etiology of keratitis caused by yeast-like fungi (6, 13, 15). C. albicans keratomycosis is associated with preexisting ocular or systemic conditions, such as epithelial defects, contact lens use, poor eyelid closure, neurotrophic cornea, diabetes, immunosuppression, and/or corneal transplantation (6, 15). Clinical management of these infections is largely dependent upon antifungal drug efficacy and penetration into corneal tissue (7, 9, 14, 15). Fungistatic azole drugs that target ergosterol biosynthesis and perturb cell membrane integrity are relatively successful in managing a variety of Candida disease manifestations (11). However, Candida has evolved sophisticated azole drug resistance mechanisms, which complicate disease management (16-18). Consequently, novel approaches need to be employed to expand antifungal treatment options.

In C. albicans, calcineurin, a serine/threonine phosphatase, is required for survival in the presence of azoles and for virulence in a murine disseminated candidiasis model (1, 4, 10, 12). We previously demonstrated that azoles act synergistically with the calcineurin inhibitor FK506 or cyclosporine A (CsA) to inhibit C. albicans in vitro (4). Here, we explore the potential for applying this drug synergy to a murine model of C. albicans keratomycosis (19). We discovered that the efficacy of topical fluconazole therapy was enhanced by genetic or pharmacological inhibition of calcineurin.

BALB/c mice were immunosuppressed with methylprednisolone (100 mg/kg of body weight) 5 days before, 1 day before, and 1 day after inoculation to rapidly establish and maintain infections (19). An intramuscular injection of a ketamine (10 mg/ml)-xylazine (1 mg/ml) mixture was given, and the right cornea of each animal was scarred with a 28.5-gauge needle. A 5-microliter suspension containing 106 C. albicans wild-type (SC5314) (5) cells was evenly distributed over the scarred cornea. A disease grading scale from 0 (no disease) to 4 (severe disease) was established by an ophthalmologist who was blinded to the infecting C. albicans strain and drug treatment (Fig. 1). The animals were randomly assigned to treatment groups, and treatment was begun when at least one animal in each group achieved a grade 3 or higher infection (Fig. 1). The treated animals received six doses of 2% CsA (10 μg/dose), 0.2% fluconazole (1 μg/dose), or 0.2% fluconazole (1 μg/dose) plus 2% CsA (10 μg/dose) over a 4-day period. For combination therapy, the drugs were administered in succession with at least 2 minutes between doses. Corneas were observed at 1.6× magnification with a Zeiss biomicroscope and slit lamp and scored daily. The results from two independent experiments were combined and analyzed.

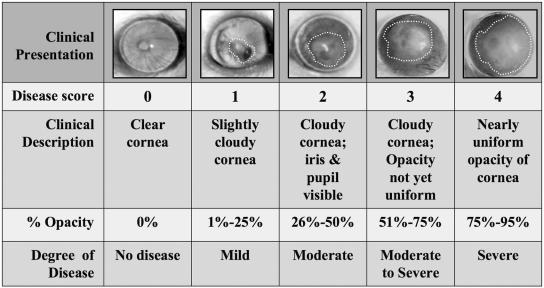

FIG. 1.

Ocular grading scale used to determine disease score. The right eyes of immunosuppressed animals were scarred and inoculated with C. albicans cells. The infections were photographed using a 35-mm camera mounted with a Zeiss biomicroscope slit lamp. The white dotted lines designate the areas of focal lesions. The photographs and corresponding clinical criteria describe the degrees of infection. Scores that deviated from the whole-number grading scale were assigned fractional values in 0.25 increments in reference to the nearest whole-number score. The photographs represent the criteria for the grading scale and do not reflect the disease progression in a single animal.

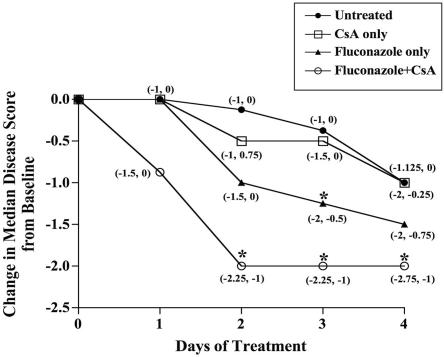

All treatment groups exhibited comparable median disease scores prior to treatment (data not shown). The median disease scores of animals treated with combination therapy declined more rapidly than those of all other treatment groups (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2). Combination therapy significantly reduced median disease scores in 2 days (P < 0.0001) compared to those of untreated animals, while fluconazole monotherapy required 3 days (P = 0.0085) (Fig. 2). Thus, combination therapy improved corneal infections more rapidly than fluconazole monotherapy. The daily change in median disease scores for untreated and CsA-treated animals did not differ (P > 0.2) (Fig. 2). When only grade 4 infections were considered, the disease resolution pattern of animals receiving combination therapy resembled that of the collective group (data not shown). Therefore, combination treatment was effective regardless of disease severity.

FIG.2.

The fluconazole-CsA combination rapidly clears wild-type infections. By day 2, the change from the baseline median disease score for animals treated with combination therapy was significantly different from that of untreated animals (P < 0.0001), while fluconazole-treated animals required 3 days of treatment to exhibit a significant difference from untreated animals (P = 0.0085). Descriptive statistics of the median disease scores (plus the first and third quartiles) were obtained for each day based on drug treatment using two-sided tests. The significance of the median changes from baseline was assessed within groups using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. The differences among groups with respect to response at each time point were assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test for medians. Pairwise comparisons between groups were assessed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test for medians. Bonferonni's adjusted alpha levels were applied to sets of pairwise tests. Analyses were carried out using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS), and the graphs were created with PRISM 4.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California). Animals were untreated (n = 28) or treated with CsA (n = 13), fluconazole (n = 17), or both drugs (n = 22). The values in parentheses represent the first and third quartiles. Intersecting data points with only one label indicate identical values. The asterisks designate P values of ≤0.008 compared to untreated animals.

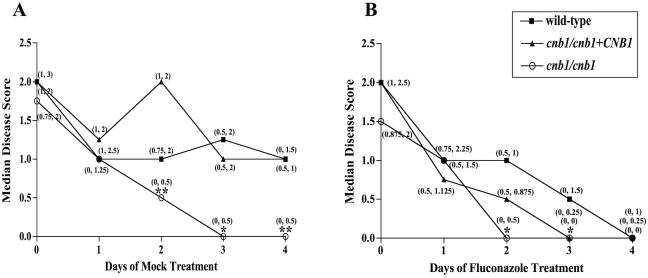

Animals were also infected with the C. albicans cnb1/cnb1 calcineurin mutant strain (JRB64) (3) or the cnb1/cnb1+CNB1 complemented calcineurin mutant strain (MCC85) (4). The calcineurin mutant is avirulent in murine disseminated candidiasis models (3, 10), and none of the cnb1/cnb1 mutant infections reached grade 3 (Fig. 1). By day 2, the median disease score of untreated cnb1/cnb1 infections was significantly lower than those of the wild type (P = 0.002) and of the CNB1-complemented mutant strains (P = 0.006) (Fig. 3A). Thus, the absence of functional calcineurin diminished C. albicans pathogenicity and accelerated disease resolution in this infection model.

FIG. 3.

Calcineurin promotes C. albicans pathogenicity in the cornea. (A) The disease severity of cnb1/cnb1 mutant infections differed from those of infections with the wild-type strain. By day 2, the median disease score of calcineurin mutant infections was significantly less than those of infections with the wild-type and the complemented calcineurin mutant (cnb1/cnb1+CNB1) strains (P = 0.002 and P = 0.006, respectively). (B) Fluconazole treatment enhanced disease resolution for all strains. By day 2, cnb1/cnb1 mutant infections exhibited a median disease score of zero and differed significantly from wild-type infections (P = 0.004). Fluconazole treatment lowered the median disease scores of cnb1/cnb1+CNB1 mutant infections to zero by day 3. The wild-type and complemented-mutant infections, which persisted with mock treatment (Fig. 3A), declined to zero with fluconazole therapy by day 3 or 4. Descriptive statistics for the median disease scores were obtained as for Fig. 2. Animals were infected with wild-type (n = 23), cnb1/cnb1 (n = 15), or cnb1/cnb1+CNB1 (n = 15) strains. The values in parentheses represent the first and third quartiles. Intersecting data points with only one label indicate identical values. *, P values of ≤0.017 compared to wild-type infections; **, P values of ≤0.017 compared to wild-type and cnb1/cnb1+CNB1 infections.

Fluconazole therapy caused the median disease scores of all infected animals to decline more rapidly than those of their untreated counterparts (Fig. 3). By day 2, the median disease score of fluconazole-treated cnb1/cnb1 infections was significantly lower than that of wild-type infections (P < 0.004) (Fig. 3B). The disease profiles of fluconazole-treated cnb1/cnb1 and cnb1/cnb1+CNB1 mutant infections were comparable (P ≥ 0.07) (Fig. 3B). Because the complemented mutant strain carries only one copy of the wild-type CNB1 gene, it may exhibit partial phenotypic complementation. Therefore, reduction in calcineurin activity substantially increased the fluconazole susceptibility of the cnb1/cnb1+CNB1 mutant strain, while complete loss of calcineurin reduced the infectivity of the cnb1/cnb1 mutants in this corneal infection model (Fig. 3). In addition, the median disease score for cnb1/cnb1 mutant infections reached zero 1 day sooner with fluconazole treatment (Fig. 3), likely owing to the fluconazole hypersensitivity previously demonstrated by calcineurin mutants (1, 3, 4, 12). Thus, the absence of functional calcineurin diminished C. albicans pathogenicity and accelerated disease resolution. This observation provided additional support for the idea that a calcineurin-dependent mechanism was responsible for the enhanced clearing observed when wild-type infections were treated with the fluconazole-CsA combination (Fig. 2).

This murine fungal keratitis model provided a unique setting to explore in vivo drug efficacy against C. albicans infection. Recent studies have demonstrated that specific host conditions can dictate strain infectivity and antifungal drug efficacy. Although C. albicans calcineurin mutants are avirulent in a murine model of disseminated candidiasis and demonstrate reduced pathogenicity in the cornea, as shown here, these mutants are not attenuated in murine vaginal or pulmonary infection models (1-3, 12). Thus, the role that calcineurin plays in C. albicans pathogenicity is dependent on the host niche. In addition, despite being a fungistatic drug, fluconazole exhibited fungicidal activity against Candida species under in vitro conditions that simulated the vaginal microenvironment (8). These findings demonstrate that in vitro studies can be applied to specific in vivo conditions to predict Candida susceptibility to certain antifungal therapies. Our findings may have broad implications, given that fluconazole and CsA are already used clinically and may be applicable to a wide range of fungi.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Sandra Stinnett for statistical data analysis and to the Duke University Medical Center Pharmacy for compounding drug formulations.

This study was supported by RO1 grants AI42159 and AI050438 from the NIH/NIAID to Joseph Heitman and in part by NIH Supplement AI050438-04S1 from the NIAID to Chiatogu Onyewu and the Research to Prevent Blindness Award to Natalie Afshari. Chiatogu Onyewu is a UNCF/Merck Graduate Student Fellow.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 August 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bader, T., B. Bodendorfer, K. Schroppel, and J. Morschhauser. 2003. Calcineurin is essential for virulence in Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 71:5344-5354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bader, T., K. Schroppel, S. Bentink, N. Agabian, G. Kohler, and J. Morschhauser. 2006. Role of calcineurin in stress resistance, morphogenesis, and virulence of a Candida albicans wild-type strain. Infect. Immun. 74:4366-4369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blankenship, J. R., F. L. Wormley, M. K. Boyce, W. A. Schell, S. G. Filler, J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 2003. Calcineurin is essential for Candida albicans survival in serum and virulence. Eukaryot. Cell. 2:422-430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cruz, M. C., A. L. Goldstein, J. R. Blankenship, M. Del Poeta, D. Davis, M. E. Cardenas, J. R. Perfect, J. H. McCusker, and J. Heitman. 2002. Calcineurin is essential for survival during membrane stress in Candida albicans. EMBO J. 21:546-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillum, A. M., E. Y. Tsay, and D. R. Kirsch. 1984. Isolation of the Candida albicans gene for orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase by complementation of S. cerevisiae ura3 and E. coli pyrF mutations. Mol. Gen. Genet. 198:179-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klotz, S. A., C. C. Penn, G. J. Negvesky, and S. I. Butrus. 2000. Fungal and parasitic infections of the eye. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:662-685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manzouri, B., G. C. Vafidis, and R. K. Wyse. 2001. Pharmacotherapy of fungal eye infections. Exp. Opin. Pharmacother. 2:1849-1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moosa, M. Y., J. D. Sobel, H. Elhalis, W. Du, and R. A. Akins. 2004. Fungicidal activity of fluconazole against Candida albicans in a synthetic vagina-simulative medium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:161-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Day, D. M. 1996. Fungal keratitis. In J. S. Pepose, G. N. Holland, and K. R. Wilhemus (ed.), Ocular infections and immunity. Mosby, St. Louis, Mo.

- 10.Onyewu, C., F. L. Wormley, Jr., J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 2004. The calcineurin target, Crz1, functions in azole tolerance but is not required for virulence of Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 72:7330-7333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rex, J. H., T. J. Walsh, J. D. Sobel, S. G. Filler, P. G. Pappas, W. E. Dismukes, J. E. Edwards, et al. 2000. Practice guidelines for the treatment of candidiasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:662-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanglard, D., F. Ischer, O. Marchetti, J. Entenza, and J. Bille. 2003. Calcineurin A of Candida albicans: involvement in antifungal tolerance, cell morphogenesis and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 48:959-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanure, M. A., E. J. Cohen, S. Sudesh, C. J. Rapuano, and P. R. Laibson. 2000. Spectrum of fungal keratitis at Wills Eye Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Cornea 19:307-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas, P. A. 2003. Current perspectives on ophthalmic mycoses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 16:730-797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas, P. A. 2003. Fungal infections of the cornea. Eye 17:852-856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White, T. C. 1998. Antifungal drug resistance in Candida albicans. ASM News 63:427-433. [Google Scholar]

- 17.White, T. C., S. Holleman, F. Dy, L. F. Mirels, and D. A. Stevens. 2002. Resistance mechanisms in clinical isolates of Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1704-1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White, T. C., K. A. Marr, and R. A. Bowden. 1998. Clinical, cellular, and molecular factors that contribute to antifungal drug resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:382-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu, T. G., K. R. Wilhelmus, and B. M. Mitchell. 2003. Experimental keratomycosis in a mouse model. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44:210-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]