Abstract

The activities of anidulafungin and caspofungin against Candida glabrata were evaluated. MICs, 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50 values), and IC90 values for anidulafungin were lower than those for caspofungin for 16 of 18 strains tested. Anidulafungin has potent in vitro activity against C. glabrata that is maintained against isolates with elevated caspofungin MICs.

Infections caused by Candida glabrata have been reported to be increasing in frequency (19, 30) and are associated with high mortality rates for the elderly, immunocompromised patients, and patients in intensive care units (2, 11, 27). Treatment may be complicated by the variable susceptibility of C. glabrata to fluconazole and by reduced response rates to other azole antifungals in breakthrough infections (2, 11, 22, 26, 29).

The echinocandins have emerged as an effective treatment strategy for invasive candidiasis. Although susceptibility breakpoints are not currently established, broth microdilution studies have demonstrated relatively good activity for each member of this class against Candida isolates, including non-C. albicans species (13, 28). However, case reports describing clinical failures of caspofungin associated with reduced in vitro activity against C. albicans, C. glabrata, and C. krusei have begun to emerge (6, 7, 9, 10, 14, 21). It is currently unknown if other echinocandins would maintain potency at clinically relevant exposures in the face of diminished caspofungin activity. The objective of this study was to compare the in vitro activities and pharmacodynamics of anidulafungin and caspofungin against Candida glabrata isolates over a range of clinically achievable concentrations.

(Part of this work was presented previously [N. P. Wiederhold, J. R. Graybill, L. K. Najvar, and D. S. Burgess, Abstr. 45th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. M-2160, 2005].)

Eighteen Candida glabrata isolates from the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio were tested. Stock solutions of anidulafungin (Vicuron Pharmaceuticals, King of Prussia, PA) and caspofungin (Merck & Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ) were prepared by dissolving drug powders in dimethyl sulfoxide and water, respectively.

Microdilution broth susceptibility testing was performed in duplicate according to the CLSI M27-A2 method in RPMI growth medium buffered with 0.165 M 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (15). The MIC2 was defined as the lowest concentration of anidulafungin or caspofungin that caused a significant decrease in turbidity (≥50%) compared to that of the growth control, and the MIC0 was defined as the lowest concentration resulting in no visual growth. The minimum fungicidal concentration (MFC) was measured as previously described (5).

The 2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide (XTT) colorimetric assay was performed in triplicate as previously reported (12). Final anidulafungin concentrations ranged from 0.015 to 32 μg/ml, and those of caspofungin ranged from 0.06 to 128 μg/ml. The absorbance was read at 492 nm, and readings were converted to percent absorbance, with values for growth control wells set at 100% and those for medium control wells set at 0%. XTT reduction assay data were fit to a four-parameter inhibitory sigmoid model, using computer curve fitting software (Prism 4; GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA), to derive 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) and IC90 values. The goodness of fit for each isolate/drug was assessed by the R2 value and the standard error of the IC50 value. The IC50 and IC90 values were not determined if minimal or no reduction in formazan absorbance was observed with increasing drug concentrations.

Time-kill studies were performed in duplicate on isolates with caspofungin MICs of ≥8 μg/ml, using previously described methods (8). The anidulafungin and caspofungin concentrations tested were 0.5, 1.0, 4.0, 8.0, and 16 μg/ml. These are within the range achieved clinically for both agents (3, 4, 25). Fungicidal activity was defined as a ≥3-log10 (99.9%) reduction in CFU from the starting inoculum.

Anidulafungin MICs ranged from 0.125 to 4 μg/ml and were at least two dilutions lower than those of caspofungin (range, 1 to 64 μg/ml) for 16 of the 18 isolates tested, including the three isolates with elevated caspofungin MICs (Table 1). Similarly, the MFCs for anidulafungin (range, 0.25 to 8 μg/ml) were ≥2 dilutions lower than those of caspofungin (1 to ≥128 μg/ml) for 14 of the 18 isolates tested. Anidulafungin remained fungicidal against the three strains with elevated caspofungin MFCs (≥64 μg/ml).

TABLE 1.

MIC, MFC, IC50, and IC90 values for anidulafungin and caspofungin against C. glabrata isolates

| Isolate | Anidulafungin value

|

Caspofungin value

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC2/MIC0/MFC | IC50/IC90 | R2 | MIC2/MIC0/ MFC | IC50/IC90 | R2 | |

| 1 | 0.25/0.5/0.5 | 0.063/0.075 | 0.97 | 1/2/4 | 0.81/0.83 | 0.91 |

| 2 | 0.125/0.25/0.25 | 0.11/0.18 | 0.93 | 1/1/2 | 0.52/0.60 | 0.96 |

| 3 | 0.125/0.25/0.25 | 0.039/0.11 | 0.86 | 1/2/4 | 0.55/0.61 | 0.95 |

| 4 | 0.125/0.25/0.25 | 0.086/0.18 | 0.91 | 1/2/2 | 0.91/1.1 | 0.89 |

| 5 | 0.125/0.25/0.25 | 0.15/0.65 | 0.83 | 1/2/2 | 0.64/0.85 | 0.89 |

| 6 | 1/2/4 | 0.65/2.4 | 0.96 | 2/2/128 | 1.8/23 | 0.73 |

| 7 | 0.125/0.25/0.5 | 0.092/0.15 | 0.96 | 1/1/2 | 0.57/0.67 | 0.95 |

| 8 | 0.25/0.25/0.5 | 0.049/0.16 | 0.94 | 1/1/2 | 0.90/1.0 | 0.82 |

| 9 | 0.25/0.5/0.5 | 0.13/0.15 | 0.88 | 1/1/2 | 0.94/1.0 | 0.91 |

| 10 | 0.125/0.25/1 | 0.11/0.19 | 0.81 | 1/1/2 | 0.86/1.2 | 0.91 |

| 11 | 0.125/0.25/4 | 0.071/0.12 | 0.98 | 1/1/1 | 0.91/0.98 | 0.86 |

| 12 | 0.125/0.25/0.5 | 0.11/0.12 | 0.93 | 1/1/4 | 0.84/0.94 | 0.95 |

| 13 | 0.25/0.25/1 | 0.053/0.38 | 0.89 | 1/1/2 | 0.74/1.0 | 0.89 |

| 14 | 0.125/0.125/1 | 0.062/0.21 | 0.92 | 1/1/2 | 0.90/0.99 | 0.90 |

| 15 | 0.125/0.125/1 | 0.11/0.13 | 0.83 | 1/1/4 | 0.83/0.93 | 0.94 |

| 16 | 1/2/4 | 0.17/7.8 | 0.78 | 4/8/64 | NDa | ND |

| 17 | 2/4/8 | 0.83/5.3 | 0.93 | 64/64/>128 | ND | ND |

| 18 | 0.5/4/8 | 2.4/3.6 | 0.90 | 2/64/64 | ND | ND |

ND, IC50 and IC90 values were not determined because of minimal or no reduction in formazan absorbance with increasing drug concentrations.

The potency of anidulafungin was greater than that of caspofungin, as evidenced by a lower IC50 value for each strain evaluated (Table 1). Similarly, the IC90 values for anidulafungin were also lower than those for caspofungin against all isolates. Against the isolates with caspofungin MICs of ≥8 μg/ml, only the highest concentration of caspofungin tested (128 μg/ml) resulted in a >90% reduction in viability, while anidulafungin maintained its potency (IC50 range, 0.17 to 2.4 μg/ml; IC90 range, 3.6 to 7.8 μg/ml).

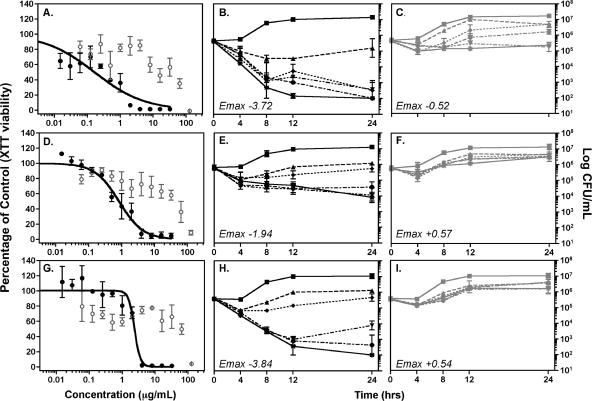

These results are supported by data from time-kill studies (Fig. 1). Against C. glabrata isolate 16, anidulafungin at 1 μg/ml resulted in a >3-log10 CFU/ml decrease in the starting inoculum at 24 h, compared to a 0.43-log10 CFU/ml reduction for caspofungin at 16 μg/ml. Anidulafungin at 4 μg/ml was fungicidal against isolate 18, in contrast to the 0.54-log10 CFU/ml increase observed with caspofungin at 16 μg/ml. Minimal activity was also observed for caspofungin against C. glabrata isolate 17 at the highest concentration tested (0.65-log10 increase in CFU/ml at 16 μg/ml). Although anidulafungin was not fungicidal against this isolate, concentrations of ≥4 μg/ml did result in reductions in colony counts (≥1.74-log10 CFU/ml decrease).

FIG. 1.

Dose-response curves (A, D, and G) and time-kill plots (B, C, E, F, H, and I) for anidulafungin and caspofungin against C. glabrata isolates with caspofungin MICs of ≥8 μg/ml. (A, B, and C) C. glabrata isolate 16; (D, E, and F) C. glabrata isolate 17; (G, H, and I) C. glabrata isolate 18. Symbols in dose-response curves (A, D, and G) show means ± standard errors for experiments performed in triplicate with anidulafungin (•) and caspofungin (○). Curves were generated by fitting XTT data to a four-parameter inhibitory sigmoid model. Symbols in time-kill plots (B, C, E, F, H, and I) show the mean values for log10 CFU/ml versus time for anidulafungin (B, E, and H) and caspofungin (C, F, and I) against C. glabrata isolates with caspofungin MICs of ≥8 μg/ml. Drug concentrations: ▪, control; ▴, 0.5 μg/ml; ⧫, 1 μg/ml; •, 4 μg/ml; ▾, 8 μg/ml; and *, 16 μg/ml. Symbols represent the means ± standard errors for experiments performed in duplicate for each drug. Emax values represent maximum log10 reductions in CFU/ml for anidulafungin and caspofungin against each isolate at 24 h.

Surveillance studies have reported relatively good activities for the echinocandins compared to other antifungals against Candida species, including non-C. albicans and fluconazole-resistant isolates (1, 5, 16, 17, 24). Against the isolates of C. glabrata tested for this study, anidulafungin had greater in vitro potency than did caspofungin, as evidenced by lower MIC and MFC values. The enhanced potency of anidulafungin against C. glabrata isolates is also supported by pharmacodynamic data from XTT and time-kill assays and was maintained against C. glabrata isolates with elevated caspofungin MICs.

While no strong correlation exists between susceptibility data and clinical success in the treatment of invasive fungal infections, in vitro and in vivo data suggest that antifungal MICs may be predictive of responses to therapy (7, 9). Furthermore, antifungal resistance is associated with clinical failure (9, 18, 20, 23). Recent reports suggested that this may also be true for caspofungin in the setting of elevated MICs (6, 7, 9, 10, 14, 21). Due to the difficulty in treating invasive candidiasis that is unresponsive to prior therapy, further studies investigating the utility of anidulafungin in this setting are warranted.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by a grant from Vicuron Pharmaceuticals to J.R.G.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 August 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arevalo, M. P., A. J. Carrillo-Munoz, J. Salgado, D. Cardenes, S. Brio, G. Quindos, and A. Espinel-Ingroff. 2003. Antifungal activity of the echinocandin anidulafungin (VER002, LY-303366) against yeast pathogens: a comparative study with M27-A microdilution method. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:163-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodey, G. P., M. Mardani, H. A. Hanna, M. Boktour, J. Abbas, E. Girgawy, R. Y. Hachem, D. P. Kontoyiannis, and I. I. Raad. 2002. The epidemiology of Candida glabrata and Candida albicans fungemia in immunocompromised patients with cancer. Am. J. Med. 112:380-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dowell, J. A., W. Knebel, T. Ludden, M. Stogniew, D. Krause, and T. Henkel. 2004. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of anidulafungin, an echinocandin antifungal. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 44:590-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dowell, J. A., M. Stogniew, D. Krause, T. Henkel, and I. E. Weston. 2005. Assessment of the safety and pharmacokinetics of anidulafungin when administered with cyclosporine. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 45:227-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Espinel-Ingroff, A. 1998. Comparison of in vitro activities of the new triazole SCH56592 and the echinocandins MK-0991 (L-743,872) and LY303366 against opportunistic filamentous and dimorphic fungi and yeasts. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2950-2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hakki, M., J. F. Staab, and K. A. Marr. 2006. Emergence of a Candida krusei isolate with reduced susceptibility to caspofungin during therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2522-2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hernandez, S., J. L. Lopez-Ribot, L. K. Najvar, D. I. McCarthy, R. Bocanegra, and J. R. Graybill. 2004. Caspofungin resistance in Candida albicans: correlating clinical outcome with laboratory susceptibility testing of three isogenic isolates serially obtained from a patient with progressive Candida esophagitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1382-1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klepser, M. E., E. J. Ernst, R. E. Lewis, M. E. Ernst, and M. A. Pfaller. 1998. Influence of test conditions on antifungal time-kill curve results: proposal for standardized methods. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1207-1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krogh-Madsen, M., M. C. Arendrup, L. Heslet, and J. D. Knudsen. 2006. Amphotericin B and caspofungin resistance in Candida glabrata isolates recovered from a critically ill patient. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42:938-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laverdiere, M., R. G. Lalonde, J. G. Baril, D. C. Sheppard, S. Park, and D. S. Perlin. 2006. Progressive loss of echinocandin activity following prolonged use for treatment of Candida albicans oesophagitis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:705-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malani, A., J. Hmoud, L. Chiu, P. L. Carver, A. Bielaczyc, and C. A. Kauffman. 2005. Candida glabrata fungemia: experience in a tertiary care center. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41:975-981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meletiadis, J., J. W. Mouton, J. F. Meis, B. A. Bouman, P. J. Donnelly, and P. E. Verweij. 2001. Comparison of spectrophotometric and visual readings of NCCLS method and evaluation of a colorimetric method based on reduction of a soluble tetrazolium salt, 2,3-bis [2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-[(sulfenylamino) carbonyl]-2H-tetrazolium-hydroxide], for antifungal susceptibility testing of Aspergillus species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4256-4263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Messer, S. A., J. T. Kirby, H. S. Sader, T. R. Fritsche, and R. N. Jones. 2004. Initial results from a longitudinal international surveillance programme for anidulafungin (2003). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54:1051-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller, C. D., B. W. Lomaestro, S. Park, and D. S. Perlin. 2006. Progressive esophagitis caused by Candida albicans with reduced susceptibility to caspofungin. Pharmacotherapy 26:877-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NCCLS. 2002. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts; approved standard. NCCLS document M27-A2. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 16.Odds, F. C., M. Motyl, R. Andrade, J. Bille, E. Canton, M. Cuenca-Estrella, A. Davidson, C. Durussel, D. Ellis, E. Foraker, A. W. Fothergill, M. A. Ghannoum, R. A. Giacobbe, M. Gobernado, R. Handke, M. Laverdiere, W. Lee-Yang, W. G. Merz, L. Ostrosky-Zeichner, J. Peman, S. Perea, J. R. Perfect, M. A. Pfaller, L. Proia, J. H. Rex, M. G. Rinaldi, J. L. Rodriguez-Tudela, W. A. Schell, C. Shields, D. A. Sutton, P. E. Verweij, and D. W. Warnock. 2004. Interlaboratory comparison of results of susceptibility testing with caspofungin against Candida and Aspergillus species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3475-3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ostrosky-Zeichner, L., J. H. Rex, P. G. Pappas, R. J. Hamill, R. A. Larsen, H. W. Horowitz, W. G. Powderly, N. Hyslop, C. A. Kauffman, J. Cleary, J. E. Mangino, and J. Lee. 2003. Antifungal susceptibility survey of 2,000 bloodstream Candida isolates in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3149-3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Panackal, A. A., J. L. Gribskov, J. F. Staab, K. A. Kirby, M. Rinaldi, and K. A. Marr. 2006. Clinical significance of azole antifungal drug cross-resistance in Candida glabrata. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:1740-1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pappas, P. G., J. H. Rex, J. Lee, R. J. Hamill, R. A. Larsen, W. Powderly, C. A. Kauffman, N. Hyslop, J. E. Mangino, S. Chapman, H. W. Horowitz, J. E. Edwards, and W. E. Dismukes. 2003. A prospective observational study of candidemia: epidemiology, therapy, and influences on mortality in hospitalized adult and pediatric patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37:634-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pappas, P. G., J. H. Rex, J. D. Sobel, S. G. Filler, W. E. Dismukes, T. J. Walsh, and J. E. Edwards. 2004. Guidelines for treatment of candidiasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:161-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pelletier, R., I. Alarie, R. Lagace, and T. J. Walsh. 2005. Emergence of disseminated candidiasis caused by Candida krusei during treatment with caspofungin: case report and review of literature. Med. Mycol. 43:559-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perfect, J. R., K. A. Marr, T. J. Walsh, R. N. Greenberg, B. DuPont, J. de la Torre-Cisneros, G. Just-Nubling, H. T. Schlamm, I. Lutsar, A. Espinel-Ingroff, and E. Johnson. 2003. Voriconazole treatment for less-common, emerging, or refractory fungal infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:1122-1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rex, J. H., and M. A. Pfaller. 2002. Has antifungal susceptibility testing come of age? Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:982-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roling, E. E., M. E. Klepser, A. Wasson, R. E. Lewis, E. J. Ernst, and M. A. Pfaller. 2002. Antifungal activities of fluconazole, caspofungin (MK0991), and anidulafungin (LY 303366) alone and in combination against Candida spp. and Crytococcus neoformans via time-kill methods. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 43:13-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone, J. A., S. D. Holland, P. J. Wickersham, A. Sterrett, M. Schwartz, C. Bonfiglio, M. Hesney, G. A. Winchell, P. J. Deutsch, H. Greenberg, T. L. Hunt, and S. A. Waldman. 2002. Single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of caspofungin in healthy men. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:739-745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.vanden Bossche, H., P. Marichal, F. C. Odds, L. Le Jeune, and M. C. Coene. 1992. Characterization of an azole-resistant Candida glabrata isolate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:2602-2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Viscoli, C., C. Girmenia, A. Marinus, L. Collette, P. Martino, B. Vandercam, C. Doyen, B. Lebeau, D. Spence, V. Krcmery, B. De Pauw, and F. Meunier. 1999. Candidemia in cancer patients: a prospective, multicenter surveillance study by the Invasive Fungal Infection Group (IFIG) of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Clin. Infect. Dis. 28:1071-1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiederhold, N. P., and R. E. Lewis. 2003. The echinocandin antifungals: an overview of the pharmacology, spectrum and clinical efficacy. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 12:1313-1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wingard, J. R., W. G. Merz, M. G. Rinaldi, C. B. Miller, J. E. Karp, and R. Saral. 1993. Association of Torulopsis glabrata infections with fluconazole prophylaxis in neutropenic bone marrow transplant patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:1847-1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wisplinghoff, H., T. Bischoff, S. M. Tallent, H. Seifert, R. P. Wenzel, and M. B. Edmond. 2004. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39:309-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]