Abstract

Achondroplasia, the most common form of dwarfism in man, is a dominant genetic disorder caused by a point mutation (G380R) in the transmembrane region of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3). We used gene targeting to introduce the human achondroplasia mutation into the murine FGFR3 gene. Heterozygotes for this point mutation that carried the neo cassette were normal whereas neo+ homozygotes had a phenotype similar to FGFR3-deficient mice, exhibiting bone overgrowth. This was because of interference with mRNA processing in the presence of the neo cassette. Removal of the neo selection marker by Cre/loxP recombination yielded a dominant dwarf phenotype. These mice are distinguished by their small size, shortened craniofacial area, hypoplasia of the midface with protruding incisors, distorted brain case with anteriorly shifted foramen magnum, kyphosis, and narrowed and distorted growth plates in the long bones, vertebrae, and ribs. These experiments demonstrate that achondroplasia results from a gain-of-FGFR3-function leading to inhibition of chondrocyte proliferation. These achondroplastic dwarf mice represent a reliable and useful model for developing drugs for potential treatment of the human disease.

Four fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs) are known (1), and >50 mutations in three of them (FGFR1, 2, and 3) recently have been implicated in congenital skeletal and cranial disorders (reviewed in refs. 2–4). Achondroplasia, the most common form of dwarfism, was shown to be linked to a single point mutation, G380R, in the transmembrane region of FGFR3 (5, 6). FGFR3 is expressed mainly by developing bones, brain, lung, and spinal cord (7, 8), and FGFR3-deficient mice show enhanced endochondral bone growth, expansion of their growth plate, and increased chondrocyte proliferation (9, 10). Thus, FGFR3 is a negative regulator of bone growth. Several experiments at the cellular level indicated that the Ach mutation (G380R) results in a constitutive activation of the receptor in a ligand-independent manner (11–13). It was suggested that this is because of stabilization of receptor dimers, a prerequisite for signal transduction in these receptors (14). This is also consistent with the constitutive activation by dimer formation described for an erbB2 (neu) receptor mutant, which carries a Val-to-Glu mutation in an analogous position to that of the FGFR3 variant in its transmembrane region (15). It is likely that, in many of the other mutations in FGFR1–3, the underlying mechanism of receptor activation is also through stabilization of receptor dimers because many of these mutations result in unpaired cysteines that may enhance inter-receptor disulfide bonds (2–4).

To generate an animal model for this type of mutation and to study the role of the mutated FGFR3 in vivo, we used gene targeting to introduce the achondroplasia mutation (G380R) into murine FGFR3. This resulted in a dominant dwarf phenotype that exhibits many of the features of human achondroplasia. This is an indication from in vivo data for the gain-of-function nature of this mutation as the cause of achondroplasia. The dwarf achondroplastic mouse represents a useful model to study the development of this disorder and to search for treatment of the human disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of Targeting Vector.

A single phage was isolated from a mouse 129/SV fix DNA library (Stratagene) and contained the entire FGFR3 gene (16). To construct the targeting vector, three separate gene fragments were subcloned into pBluescript II KS(+) (Stratagene): (i) A 4.25-kilobase (kb) HindIII/XbaI fragment containing exons 10–19 was used to generate the G/A mutation at codon 374. The mutation was introduced into a HindIII/SmaI subclone containing exon10 by using the four-oligonucleotide PCR mutagenesis method. The sense (5′-GCGTCCTCAGCTACAGGGTGGTC 3′) and antisense (5′-GACCACCCTGTAGCTGAGGACGC 3′) oligonucleotides both contained the mutation (underlined), and the T3 and T7 primers were from the pBluescript II KS(+) flanks. The product was cut with HindIII and SmaI and was replaced the homologous fragment in subclone 1. (ii) The 3.0-kb EcoRI/HindIII fragment encompassing exons 5–9 then was joined to subclone 1 to generate plasmid 1+2. (iii) The 1.8-kb KpnI/EcoRI fragment containing exon 4, and part of exon 5, was used to insert a polylinker containing the sites: 5′-XhoI-HincII-BglII-3′ into the unique BglII site. The targeting construct was generated in the vector Osdupdel, which contains MCI neo flanked by loxP and thymidine kinase under control of 3′ phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) (a gift from O. Smithies, Univ. of North Carolina), as follows: the KpnI/BamHI (1.3-kb) fragment from subclone 3 was ligated to the KpnI/BamHI sites of the vector downstream to the neo gene to form the 5′ region of homology. The XhoI/EcoRI fragment (0.3-kb) from subclone 3 and the EcoRI/XbaI fragment from subclone 1+2 (6.7-kb) were ligated to the XhoI/NheI sites between the neo and the thymidine kinase genes to form the 3′ homology region. The transcription orientation of the FGFR3 gene and the neo marker are opposite. We noted that the neo marker had a deletion of 53 bp at the 3′ end, which included the polyadenylation signal.

Generation of FGFR3 Mutant Mice.

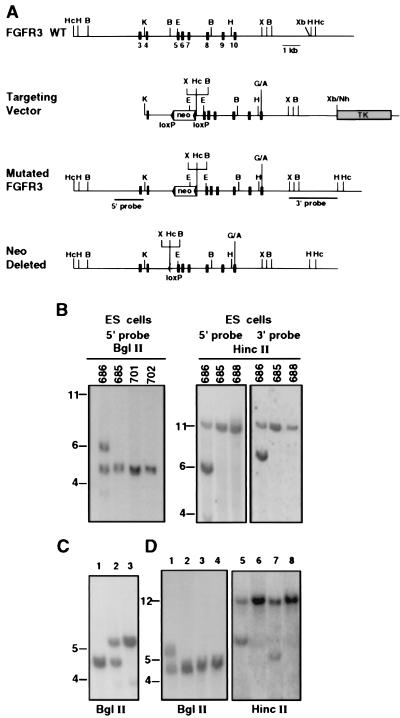

Culture and selection of embryonic stem (ES) cells (R1 cell line of 129/SV mouse) and the screening of the targeted clones were performed as described (17) by using negative (ganciclovir) and positive (G-418) selection. Cell clones were screened by Southern blot analysis by using BglII digestion and probing with the 1.5-kb 5′ probe derived by PCR from sequences upstream to the KpnI site in intron 3 (see Fig. 1). This analysis also was verified by HincII-digested DNA by using both the 5′ probe and 3′ probe based on the HincII site inserted into the polylinker at intron 4 (Fig. 1B). The HincII digest also was used to detect the mutant allele after the Cre-mediated deletion of the neo (See Fig. 1D). Clones that carried homologous recombinant containing the mutant FGFR3 were aggregated with eight-cell embryos (18) of MF1 mice. The resulting chimeric mice were crossed with MF1 females, and heterozygotic mutants were identified by Southern blot analysis of tail DNA. Heterozygous mice were mated with PGK-Crem mice (19) to delete the neo marker. The mouse genotypes were identified by Southern blots of tail DNA.

Figure 1.

Strategy used to mutate the mouse FGFR3 via gene targeting. (A) The wild-type FGFR3, with exons 3–10 marked (see ref. 16), and the targeting vector (containing intron 3 to exon 19) after mutating codon 374 (G/A), which changed Gly to Arg. Insertion of the neo cassette at intron 4 and the polylinker added 3′ to the neo are shown. (B) Mutated FGFR3 was detected in ES cells after BglII digestion by using the 5′ probe and after HincII digestion by using the 5′ and 3′ probes. Numbers represent individual ES clones. (C) Analysis of tail DNA from interheterozygote mating. Lanes: 1, wild type; 2, FGFR3G374R heterozygote; 3, FGFR3G374R homozygote. (D) Detection of neo deletion in offspring from mating FGFR3G374Rneo+ heterozygote with PGK-Crem mice. Lanes: 1 and 5, control FGFR3G374Rneo+ heterozygote; 2 and 6, control wild-type mouse; 3 and 7, FGFR3G374Rneo− heterozygote; 4 and 8, wild-type littermates. DNA blots were analyzed with the 5′ probe. Deletion of neo resulted in reduction in the size of the recombinant allele by 1.2 kb. The expected sizes of the HincII fragments detected by the 5′ or 3′ probes are 6.2 and 7.7 kb, respectively. The wild-type allele gives a band of 12.5 kb. The expected sizes of the BglII fragments are 4.6 kb (16) and 5.6 kb in the wild-type and recombinant allele, respectively. B, BglII; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; Hc, HincII; K, KpnI; X, XhoI; Xb, XbaI.

Skeletal and Histological Analysis.

Skeletal and histological preparations were produced as described (20). Biometry was performed electronically. The brain was observed after perfusion with 2.5% paraformaldehyde. Paraffin sections, staining, alkaline phosphatase activity determination, and in situ hybridization were performed as described (21). Animal care was in accordance with the Weizmann Institute guidelines.

RESULTS

Generation of Mice with Mutant FGFR3.

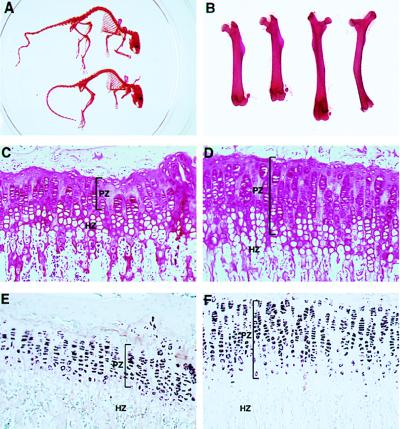

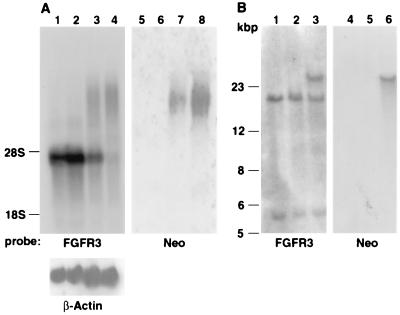

To generate a mouse model for achondroplasia, we isolated the mouse FGFR3 gene and introduced a G-to-A point mutation, changing Gly (GGG) to Arg (AGG) in codon 374 (the ortholog of human codon 380), which is located in exon 10. This point mutation (FGFR3G374R) was incorporated into a targeting construct, including a floxed neo cassette in intron 4. Other than this mutation, the coding sequence in the construct, which included exons 4–19 (16), was unchanged, but new restriction sites 3′ to the neo cassette were introduced to facilitate molecular analysis (Fig. 1). After homologous recombination in ES cells, heterozygotes were derived that had phenotypes indistinguishable from the wild type. Surprisingly, FGFR3G374Rneo+ homozygotes (abbreviated as neo+/neo+) exhibited a phenotype very similar to the targeted loss-of-function mutation of FGFR3 (9, 10). They were viable and fertile with kinky tails and dorsal kyphosis, exhibited overgrowth of the long bones, and displayed a greatly expanded growth plate (Fig. 2). DNA sequence analysis of exon 10 verified the presence of the G-to-A mutation in codon 374. Northern blot analysis revealed that neo+/neo+ animals lacked normal size FGFR3 mRNA (4.2 kb) but contained a novel high molecular weight RNA (≈10 kb) that hybridized with FGFR3 as well as with neo (Fig. 3A). These results suggest that the neo cassette may have interfered with the proper splicing of the transcript from the recombinant gene. We conclude that this transcriptional interference caused a loss of FGFR3 expression in the homozygote, resulting in a phenotype similar to the targeted inactivation of FGFR3 (9).

Figure 2.

Homozygotes of the FGFR3G374Rneo+ mutation display a phenotype very similar to the targeted loss of function mutation of FGFR3. (A) Homozygote mutant (upper skeleton) shows a kinky and elongated tail relative to the normal (lower skeleton); in the mutant, the long bones, especially the femur, are bent and longer than those of the wild type. (B) Comparison of two femurs from wild-type (Left) and mutant (Right). (C–F) Histological analysis of the tibia growth plates. (C and D) Hemotoxilin–eosin staining. (E and F) In situ hybridization with collagen type II probe. The mutant homozygotes (D and F) show longer growth plates compared with normal (C and E), which is particularly attributable to an increase in proliferating chondrocytes characterized by collagen type II expression. HZ, hypertrophic zone; PZ, proliferating zone.

Figure 3.

Northern and Southern blot analysis of normal and mutant mice. (A) Northern blot of brain RNA analyzed by FGFR3 cDNA and neo probes. Lanes: 1 and 5, control wild-type mouse; 2 and 6, FGFR3G374Rneo− heterozygote dwarf mouse; 3 and 7, FGFR3G374Rneo+ heterozygote, showing both FGFR3 RNA and the high molecular weight RNA that also hybridized with neo; 4 and 8, FGFR3G374Rneo+ homozygote RNA is devoid of normal size FGFR3 RNA. The blots also were hybridized with a β-actin probe to normalize RNA loading. (B) Southern blot of DNA digested with SpeI that cuts 3′ to the FGFR3 gene and in intron 2. Lanes: 1 and 4, control wild-type mouse; 2 and 5, FGFR3G374Rneo− heterozygote dwarf mouse; 3 and 6, FGFR3G374Rneo+ heterozygote. The results indicate that the neo+ heterozygote contains a band that hybridized with both neo and FGFR3 (lanes 3 and 6). In the neo− heterozygote, this band migrates like wild-type FGFR3, and no hybridization with neo was detected (lanes 2 and 5). The bottom band represents a fragment containing exons 1 and 2. An FGFR3 cDNA probe was used (7).

neo− Heterozygotes Display Dwarfism and Skeletal Defects.

Deletion of the neo cassette by mating neo+ heterozygotes to PGK-Crem “deleter” transgenic animals (19) resulted in heterozygotes distinguished by a novel phenotype. This cross yielded 50% dwarf and 50% normal offspring whereas mating the neo+ homozygotes to PGK-Crem transgenic mice resulted in 100% dwarf mice. The gross structure of FGFR3 gene in the dwarf mice (containing the FGFR3G374Rneo− mutation, abbreviated here as neo−) was identical to that of the wild type, as judged by hybridization of FGFR3 cDNA to Southern blots of DNA digested with three different enzymes (data not shown). DNA digested with SpeI, which flanks almost the entire gene (10), demonstrated that the neo+ heterozygote contains one wild-type allele (≈18 kb), which hybridized only with the FGFR3 probe, and a larger fragment, which hybridized to both FGFR3 and neo, representing the recombinant allele. The size of this fragment (≈24 kb), the only band that hybridized with the neo probe, was larger than expected from the addition of a single neo cassette (1.2 kb) to the recombinant allele. It is therefore likely that more than one neo cassette was incorporated into FGFR3. To analyze this possibility, we performed PCR on DNA derived from a neo+ heterozygote mouse by using two oligonucleotides derived from the neo sequence in opposite orientation. This yielded a 3.9-kb PCR product flanked by neo fragments. Sequence analysis of this PCR product showed that it contains the 5′ KpnI-BamHI fragment from the targeting construct followed by the neo cassette and continues with the 3′ fragment of the construct, including exons 5, 6, and 7 and ending at the middle of intron 7. The results indicate that two such truncated fragments of the targeting construct were incorporated in tandem in a head-to-tail orientation in the recombinant allele. These insertions did not alter the size of the fragments detected by hybridization with the external probes. The Cre-recombinase removed all of these fragments together with the neo cassettes, yielding the wild-type size DNA fragment of FGFR3 (Fig. 3B, lane2). Sequencing of the DNA of dwarf mice in the region joining the 5′ and 3′ regions of homology of the construct revealed only a single loxP sequence, as expected from Cre/loxP recombination. The absence of neo cassettes in the DNA of the dwarf mice is correlated with the Northern blot analysis, which showed that the neo− heterozygotes contain only FGFR3 mRNA of wild-type size (Fig. 3A, lane2), in contrast to the neo+ heterozygotes, which contain both a high molecular weight mRNA species that hybridizes with both FGFR3 and neo and a normal-sized mRNA (Fig. 3A, lane3). Thus, removal of the neo cassettes resulted in a dominant dwarf phenotype that was associated with an FGFR3 transcript of normal size.

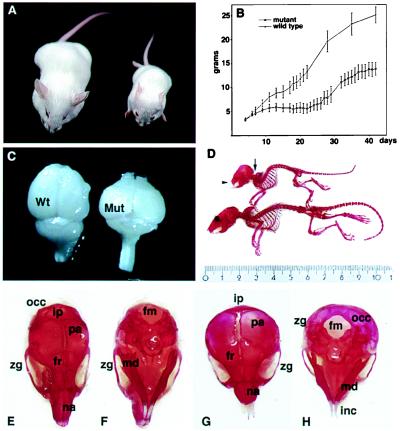

The phenotype of the neo− heterozygotes that carried the G374R point mutation is a model for human achondroplasia (Fig. 4A). The weight of these mice was half or less of their wild-type littermates (Fig. 4B), and they could be distinguished by a rounded head (Fig. 4 A, D, and G) by as early as 10 days of age. In addition, the incisors of the dwarf mice did not align normally (Fig. 4 D, G, and H) because of changes in the skull. To allow normal food intake, the teeth of the dwarfs were shortened under anesthesia, and the pelleted mouse chow was softened by wetting. Even with this treatment, the weight of the mutants did not exceed 60% of the wild-type littermates. Skeletal preparations (20) revealed an overt anterior gibbus (humpback), probably attributable to the nearly perpendicular angle between the skull and the cervical vertebrae, resulting in extreme curvature of the cervical and upper thoracic vertebrae and distorting the thorax and the anterior girdle (Fig. 4D). On close observation of the skull, extreme shortening of the nasal and frontal bones and rounding of the braincase became evident (Fig. 4 E–H). The round-headed appearance of the mutant was attributable to a ventral and anterior shift of the interparietal and occipital bones, which brought the foramen magnum to the base of the skull (Fig. 4 G and H), thereby causing the thoracic gibbus and displacing the mandibula, which in turn disrupted the normal closure of the upper and lower incisors (Fig. 4 G and H). This change was accompanied by distortion of the membrane bones of the skull vault (parietal and frontal bones) and the facial area (nasal bone and maxilla). Similar changes in the base of the skull are also characteristic of human achondroplasia and may lead to brain stem compression, respiratory disturbance, and paralysis (22–24).

Figure 4.

Anatomical defects in FGFR3G374Rneo−/+ heterozygotes. (A) Dwarfism in 5-week-old mutant (right) and wild-type littermate control mouse (left). (B) Growth curve of the neo− heterozygote and wild-type mice. Mice from a cross between mutant FGFR3G374R heterozygotes and PGK-Crem mice were weighed daily from birth. At 4 weeks of age, tail DNA was analyzed by Southern blotting to determine the genotype (FGFR3G374Rneo−/+ or +/+; see Fig. 1D). There was complete correspondence between the FGFR3G374Rneo−/+ genotype and the weight curve of the affected mice (lower curve). (C) Gross distortion of the brain in dwarf mice. (D) Skeletal defects in the dwarf mice. The arrow points to the craniocervical junction and thoracic kyphosis; the arrowhead shows the facial shortening and overgrowth of incisor teeth. (E–H) Comparison of the skull of a wild-type (E and F) and dwarf (G and H) mouse. (E and G) Dorsal view. (F and H) Ventral view. fm, foramen magnum; fr, frontal bone; inc, incisor teeth; ip, interparietal bone; md, mandible; na, nasal bone; occ, occipital bone; pa, parietal bone; zg, zygomatic arch; Mut, mutant dwarf mouse.

Narrow Growth Plate Indicates Inhibition of Chondrocyte Proliferation.

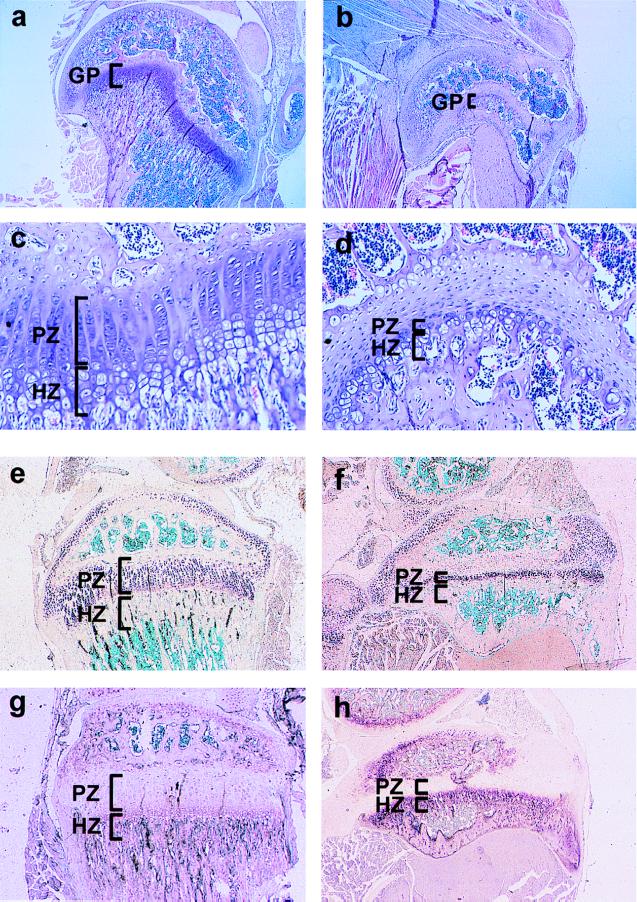

Histological observation revealed that the dwarf mouse displayed striking shortening of the growth plate (Fig. 5). The growth plate shortening in the mutant mice was greater than that reported in most cases of human achondroplasia, although, in the human disease growth plate shortening also is observed to varying degrees (25, 26). Comparison of the growth plates in dwarf and normal mice showed marked shortening with severe disorganization of the mutant growth plate in the long bones, as demonstrated in the growth plate of the tibia (Fig. 5). In most cases, the hypertrophic zone was considerably reduced or absent, and the proliferating zone was devoid of the characteristic chondrocyte columns (Fig. 5 C and D). Especially significant in the mutant tibia was the narrowing of the collagen type II-positive proliferating chondrocyte layer at the proliferating zone (Fig. 5 E and F) and the intensified alkaline phosphatase activity, a marker for differentiated chondrocytes in the hypertrophic zone (Fig. 5 G and H). These findings are consistent with inhibition of chondrocyte proliferation and precocious ossification, which may be the main cause of dwarfism in these mice.

Figure 5.

Histological analysis of the growth plates from the tibia of neo− FGFR3 heterozygotes (FGFR3G374Rneo−/+) (Right) and wild-type mice (Left). (A and B) Tibia of 30-day-old normal mouse (A) and its FGFR3G374Rneo−/+ littermate (B). (C and D) Higher magnification of the same sections. In the growth plate of the wild type, columns of proliferative and hypertrophic chondrocytes are observed (stained purple with hematoxilin and eosin). In the FGFR3G374Rneo−/+ mouse, the tibia is smaller, and the overall organization of the columns is disrupted and markedly shortened, with very few cells in the proliferative and hypertrophic zones. (E and F) In situ hybridization of the growth plate with a probe for collagen type II, a marker for proliferating chondrocytes. (G and H) Staining for alkaline phosphatase activity in the growth plate marking the hypertrophic chondrocytes. GP, growth plate; HZ, hypertrophic zone; PZ, proliferative zone.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we report the generation of achondroplastic mice by a point mutation inserted into the transmembrane domain of FGFR3. This point mutation is identical to that found in human achondroplasia (5, 6). This gene targeting resulted in two opposite phenotypes: The neo+ homozygotes were similar to targeted loss-of-function mutation of FGFR3 (9, 10) and showed bone overgrowth (Fig. 2) whereas the neo− heterozygote displayed dwarfism (Fig. 4). Removal of the neo cassettes allowed the conversion between these phenotypes because of restoration of proper mRNA processing (Fig. 3). It is clear, therefore, that the expression of the achondroplastic phenotype depends on the expression of mature mRNA transcribed from the mutant allele. The constitutive activation of the mutant FGFR3 in the dwarf mouse results in inhibition of chondrocyte proliferation at the growth plate, premature differentiation, and early cessation of bone growth. If the achondroplastic phenotype is caused by ligand-independent activation of the mutant receptor (11–13), then it is plausible that stimulation of wild-type FGFR3 by excess ligand should result in a similar effect. Indeed FGF2, a ligand for FGFR3, was found to inhibit chondrocyte proliferation and to reduce the number of hypertrophic chondrocytes in the growth plate of cultured bone (27) as well as in FGF2 transgenic mice that overexpress FGF2 (28). Hence, FGFR3 signaling, whether through excess ligand binding or because of the achondroplastic mutation, leads to inhibition of proliferation and premature differentiation of growth plate chondrocytes.

The dominant dwarf phenotype described here was caused by the activation of the mutant FGFR3 after the Cre-mediated removal of the neo cassettes. This activation is an indication from in vivo data for the gain-of-function nature of this mutation; our results also provide direct evidence that this mutation is the cause of achondroplasia. Activation of a dominant mutation is an attractive approach to generate and breed mouse models for congenital defects connected with FGF receptors (2–4). Indeed, the parental heterozygotic strains of the mutant described here are normal and highly fertile, allowing the production of numerous, viable mutant animals that can be bred with a deleter Cre mouse to yield dwarf mice. Hence, this mouse model for achondroplasia may provide an experimental system for the testing of drugs to restore normal bone formation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mr. Niv Tutka for his excellent assistance in animal care, great interest, and creativity, which were essential to this project. We thank Dr. Y. Yamada for the probe for collagen type II. This study was supported in part by a Research Center Grant from the Israel Science Fund, administered by the Israel Academy of Sciences; by the Infrastructure Laboratory program of the Israel Ministry of Science; and by ProChon Biotech, Ltd. (Nes Ziona, Israel).

ABBREVIATIONS

- FGFR3

fibroblast growth factor receptor 3

- kb

kilobase

- ES cell

embryonic stem cell

- PGK

3′ phosphoglycerate kinase

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

References

- 1.Givol D, Yayon A. FASEB J. 1992;6:3362–3369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Moerlooze L, Dickson C. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:378–385. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilkie A O. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1647–1656. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.10.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Webster M K, Donoghue D J. Trends Genet. 1997;13:178–182. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiang R, Thompson L M, Zhu Y Z, Church D M, Fielder T J, Bociar M, Winokur S T, Wasmuth J J. Cell. 1994;78:335–342. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rousseau F, Fonaventure J, Legcai-Mallet L, Pelet A, Rozet J M, Marobeaux P, Le Merrer M, Munnich A. Nature (London) 1994;371:252–254. doi: 10.1038/371252a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avivi A, Zimmer Y, Yayon A, Yarden Y, Givol D. Oncogene. 1991;6:1089–1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters K, Ornitz D, Werner S, Williams L. Dev Biol. 1993;155:423–430. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deng C, Wynshaw-Boris A, Zhou F, Kuo A, Leder P. Cell. 1996;84:911–921. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colvin J S, Bohne B A, Harding G W, McEwen D G, Ornitz D M. Nat Genet. 1996;12:390–397. doi: 10.1038/ng0496-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naski M C, Wang Q, Xu J, Ornitz D M. Nat Genet. 1996;13:233–237. doi: 10.1038/ng0696-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Webster M K, Donoghue D J. EMBO J. 1996;15:520–527. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li T, Hagasarian K, Mansukhani A, Basilico C. Oncogene. 1997;14:1397–1406. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss A, Schlessinger J. Cell. 1998;94:277–280. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81469-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiner D B, Liu J, Cohen J A, Williams W V, Green M I A. Nature (London) 1989;339:230–231. doi: 10.1038/339230a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perez-Castro A V, Wilson J, Alther M R. Genomics. 1995;30:157–162. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.9890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mansour S L, Thomas K T, Capecchi M. Nature (London) 1988;336:348–352. doi: 10.1038/336348a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagy A, Rossant J, Nagy R, Abramov-Newerly W, Roder J C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:842–848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lallemand Y, Luria V, Haffner-Krausz R, Lonai P. Transgenic Res. 1998;7:105–112. doi: 10.1023/a:1008868325009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaufman M H. The Atlas of Mouse Development. New York: Academic; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knopov V, Leach R M, Barak-Shalom T, Hurwitz S, Pines M. Bone (NY) 1995;16:329S–334S. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(94)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horton W A, Hecht J Y. In: Connective Tissue and its Heritable Diseases: Molecular Genetic and Medical Aspects. Royce P M, editor. New York: Wiley–Liss; 1993. pp. 641–675. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reid C S, Pyeritz R E, Kopits S E, Maria B L, Wang H, McPherson R W, Hurko O, Phillips J A, Rosenbaum A E. J Pediatrics. 1987;110:522–530. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80542-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson F W. Ann Neurol. 1988;24:89–93. doi: 10.1002/ana.410240117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horton W A, Hood O L, Machado M A, Campbell D. In: Human Achondroplasia: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Nicoletti B, Kopitz S E, McKusick V A, editors. New York: Plenum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rimoin D L, Hughes G N, Kaufman R L, Rosenthal R E, McAlister W H, Silberger R. N Engl J Med. 1970;283:728–735. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197010012831404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mancilla E E, De Luca F, Uyeda J A, Czerwiec F S, Baron J. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2900–2904. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.6.6032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coffin J D, Florkiewicz R Z, Neumann J, Mort-Hopkins T, Dorn G W, II, Lightfoot P, German R, Howles P N, Kier A, O’Toole B A, et al. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:1861–1873. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.12.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]