Abstract

Integrin receptors, and associated cytoplasmic proteins mediate adhesion, cell signaling and connections to the cytoskeleton. Using fluorescent protein chimeras, we analyzed initial integrin adhesion in spreading fibroblasts with Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy. Surprisingly, sequential radial projection of integrin and actin containing filopodia formed the initial cell-matrix contacts. These Cdc42-dependent, integrin-containing projections recruited cytoplasmic focal adhesion (FA) proteins in a hierarchical manner; initially talin with integrin and subsequently FAK and paxillin. Radial FA structures then anchored cortical actin bridges between them and subsequently cells reorganized their actin, a process promoted by Src, and characterized by lateral FA reorientation to provide anchor points for actin stress fibers. Finally, the nascent adhesions coalesced until they formed mature FAs.

INTRODUCTION

Cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix (ECM) is essential for a range of processes such as cell cycle progression, hemostasis, and regulation of apoptosis (Hynes, 2002). The transmembrane receptors that bind to the ECM and mediate the interaction between the ECM and the cytoskeleton are the integrins, a family of >20 heterodimeric glycoproteins (Hynes, 2002). In adherent cells, integrin ligand binding triggers an array of cytoplasmic events, such as the activation of the Rho family of GTPases (Ren et al., 1999; del Pozo et al., 2000), which regulate the organization of the cytoskeleton (Nobes and Hall, 1995; Palazzo et al., 2004), and the recruitment of a network of molecules to adhesive structures called focal adhesions (FAs). FAs are plaques containing a diverse range of molecules such as adapter proteins, kinases, and proteins that physically link the integrin receptor to actin, completing the connection to the cytoskeleton (Sastry and Burridge, 2000; Calderwood and Ginsberg, 2003).

In migrating cells, it has been established that motility is accomplished by the formation of new adhesions at the leading edge, rather than movement of existing FAs (Rottner et al., 1999; Smilenov et al., 1999; Yeo et al., 2006). Consequently, given the importance of motility in cell biology, there has been keen interest in elucidating the mechanism by which new adhesions are formed.

The generation of new adhesions is also fundamental to the ability of a cell to spread, and it has been assumed that cell spreading and migration are, in part, analogous. However, in spreading cells, unlike in migrating cells, initially no FAs are present. Hence, the cell must generate all adhesions de novo in order to adhere, flatten and become polarized. Furthermore, there is no existing cytoskeletal organization, nor activity of adhesion-dependent kinases in spreading, as opposed to migrating cells. Consequently, cell spreading presented an excellent system to investigate FA generation. In addition, an examination of cell spreading after detachment may provide important insights into postmitotic cell spreading in culture.

We examined dynamically the physical mechanism by which integrins, the cells' adhesion receptor, and cytoplasmic FA proteins, which mediate the cytoskeletal connection, were constructed into a mature adhesion during spreading. Specifically, we found that the initial integrin–matrix contacts occurred at the tips of filopodia. These initial contacts then activated the sequential recruitment of FA components to filopodia. As the cells spread, these filopodia were organized into FAs that served as anchor points for actin stress fibers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of Reporter Constructs

For reporter constructs, chimera was initially prepared using commercial green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion protein vectors (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) before subcloning into retroviral vectors. Subsequently, red fluorescent protein (RFP) variants were constructed using the GFP template. All restriction enzymes and Klenow fragment DNA polymerase were from Promega (Madison, WI). Taq DNA polymerase, used for generating DNA fragments, was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and PfuTurbo DNA polymerase and DpnI restriction enzyme, used for degenerate oligonucleotide-mediated site-directed mutagenesis, were from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). All constructs were sequenced to confirm their fidelity.

Human α1 integrin was conjugated to RFP and ligated into the pLHCX (Clontech) retroviral expression vector. The resulting chimera had a four-amino acid linker (PVAT) between the integrin C terminus and the N terminus of RFP. pLHCX-GFP-FAK was prepared as described previously (Ezratty et al., 2005). The RFP variant, pLHCX-RFP-FAK, was created in a similar manner. pEGFP-paxillin and pCDNA3-paxillin were gifts from C. Turner (SUNY, Syracuse, NY). Paxillin-GFP was subcloned into pLNXC. The paxillin-RFP variant was created similarly to the RFP variant of α1-GFP. GFP-Talin (a gift from K. Yamada, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) was cloned into pLNCX-2 before infection into NIH3T3 cells. Myc-tagged N17Rac and N17Cdc42 were a gift from S. Greenberg (Columbia University, New York, NY). Dominant-negative Cdc42 effector constructs MRCKcpc, PAK4-Δ, PAK1(-83–149), and N-WASP-H208D were gifts from G. Gundersen (Columbia University), A. Minden (Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ), G. Bokoch (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA), and S. Suetsugu (University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan), respectively. pLHCXcSrc was a gift from H. Varmus (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Institute, New York, NY).

Transfection of Reporter Constructs into NIH3T3 Cells

Transient transfections were performed in serum-containing media by using Lipofectamine Plus reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. GFP-Paxillin was stably transfected into cells by calcium phosphate precipitation. For all other constructs, a retroviral expression system was used to generate stable cell lines. Infections were performed as described previously (Pear et al., 1993). Cells were cultured in selection media (either 1 mg/ml G418 or 300 μg/ml hygromycin), and positive colonies were screened by immunofluorescence microscopy. SYF cells were from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA).

Cell Spreading Analysis

Fibronectin (FN; 1 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) or collagen IV (1 μg/ml) was coated on coverslips at 37°C for 1 h. For analysis of fixed samples, cells were trypsinized and added to coverslips in DMEM, 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 1% serum, and incubated at 37°C for varying times before fixation (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS], 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min) and permeabilization (PBS, 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 min). Cells were stained with either rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin (Invitrogen) for F-actin or antibodies to vinculin (Sigma-Aldrich), myc (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), paxillin, total focal adhesion kinase (FAK) (BD Biosciences Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), or FAKpY397 (BioSource International, Camarillo, CA). Secondary antibodies were from Invitrogen.

For determination of two-dimensional spread cell area, cells transfected with DsRed or cotransfected with DsRed and N17Cdc42 or N17Rac were trypsinized, placed on a heated (35°C) microscope stage, and allowed to spread for 2–4 h on FN-coated glass-bottomed culture dishes (MatTek, Ashland, MA) with phase contrast images captured every 20–30 min. Fluorescent images were taken at the end of each recording to identify positive cells, and spread cell area was measured using MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Alternatively, N17Cdc42- or N17Rac-transfected cells were allowed to spread for ∼20 min, fixed, and stained for myc or FAKpY397, and images were captured by total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy. For dominant-negative Cdc 42 effectors, transfected cells were allowed to spread for 30 or 60 min; they were fixed and stained for myc, hemagglutinin (HA) (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich), N-WASP (S. Suetsugu, University of Tokyo), and either FAK or FAKpY397; and images were captured by TIRF microscopy.

For TIRF live imaging experiments, cells were trypsinized, washed twice in spreading media (phenol red-free DMEM, 2% BSA, 1% serum, 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.1), added to FN- or collagen IV-coated glass-bottomed culture dishes, and placed on the microscope stage maintained at 35°C. After allowing the cells to settle for 5 min, a newly adhered cell was chosen for analysis, and images were captured every 60–120 s.

Epifluorescence and TIRF Microscopy

Epifluorescent microscopy was performed with a Nikon Optiphot microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) by using a 60× plan apo objective and filter cubes optimized for fluorescein/GFP and rhodamine/RFP fluorescence (Nikon). Images were obtained with a back-illuminated cooled charge-coupled device camera (1000 × 800 pixels; Princeton Instruments, Trenton, NJ) by using MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices).

For TIRF microscopy, samples were observed with a 60× apo objective (numerical aperture = 1.45) on a Nikon TE2000-U microscope equipped with a TIRF illuminator and fiber optic-coupled laser illumination with two separate laser lines (Ar ion (488 nm) and HeNe (543 nm) and filter cubes optimized for flourescein/Alexa488/GFP and rhodamine/RFP (Chroma Technology, Rockingham, VT). For dual-color imaging, a z488/543rpc (Chroma Technology) polychroic was used with HQ515/30m (GFP) and HQ590/50m (RFP) emission filters.

Western Blotting and Adhesion-dependent FAK Tyrosine Phosphorylation

Membranes were probed with a primary antibodies specific for either pY397 of FAK (BioSource International) followed by protein A-peroxidase (BD Biosciences Transduction Laboratories) or monoclonal antibodies FAK, paxillin, or talin (Sigma-Aldrich) followed by anti-mouse-peroxidase (Chemicon International). Western blots of FAK pY397 were reprobed with the FAK monoclonal antibody (mAb). Membranes were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL).

RESULTS

Cell Spreading Mediated by the Projection of FA Protein-containing Filopodia

To observe how FAs were generated, we first made a fluorescently labeled integrin by fusing a monomeric RFP (Campbell et al., 2002) to the cytoplasmic tail of the human α1 integrin, a subunit of the collagen IV receptor. The α1-RFP reporter was stably expressed in NIH3T3 cells (A1R cells) that do not express a collagen binding integrin (Briesewitz et al., 1993), ensuring that all adhesion events on collagen IV would be mediated by the fluorescently labeled receptor (Supplemental Figure S1). To examine cell spreading, and in particular to determine precisely the initiation of an adhesion site, we used TIRF microscopy. This technique enabled examination of the specific region where integrin–ligand interaction occurred, the bottom 100 nm of a spreading cell (Toomre and Manstein, 2001).

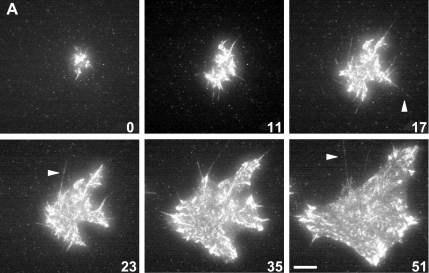

Surprisingly, adhesions in spreading cells were not initiated from a nucleation point or smaller focal complexes forming at the leading edge of a lamellapodia, as they are in migrating cells (Rottner et al., 1999; Smilenov et al., 1999). Rather, adhesions were initiated by the sequential formation of integrin-containing filopodia, which projected approximately radially to the cell centroid (Figure 1). The initial projections varied significantly in length and were, in some instances, considerably longer than the 10 μm (Figure 1, arrows, and Supplemental Video 1) previously thought to be the upper limit for filopodia length in fibroblasts (Welch and Mullins, 2002). These results were unexpected, because, although filopodia had been considered important for early spreading (Price et al., 1998), their fundamental role in generating adhesive sites throughout spreading by the continuous production of new projections had not been characterized.

Figure 1.

Cell spreading was accomplished by projection of integrin-containing filopodia. α1-RFP–expressing cells (A1R cells) were plated on collagen IV and allowed to spread. Six representative images of an entire cell at intervals throughout the spreading process visualized by TIRF microscopy (see Supplemental Video 1 for all 29 images). Numbers indicate time (minutes) after spreading began. Bar, 10 μm. Arrows indicate filopodia longer than 10 μm.

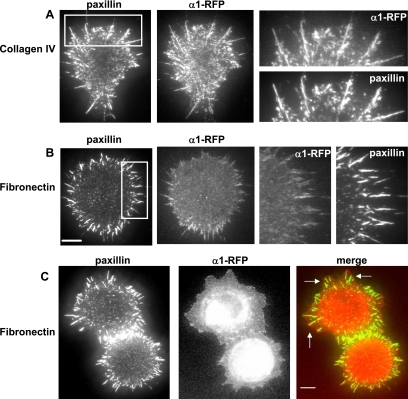

In addition to integrins, mature FAs in fully spread cells contain a variety of cytoplasmic proteins, including the adapter protein paxillin (Turner, 2000), the tyrosine kinase FAK (Mitra et al., 2005), and the ezrin, radixin, and moesin domain-containing protein talin (Calderwood and Ginsberg, 2003). In an initial examination of fixed A1R cells partially spread on collagen IV, endogenous FA proteins colocalized to integrin-containing filopodia at early spreading times (Figures 2A and S2). In addition, fluorescently labeled FA proteins behaved similarly to their endogenous counterparts, and GFP-fusions of FAK (Figure 3C), talin (Supplemental Figure S2), and paxillin (our unpublished data), when expressed in A1R cells, tracked with the receptor by forming filopodia in the earliest stages of spreading. Importantly, when adhesions were initiated in these cells on FN, interacting with the ECM via their endogenous α5β1 receptor, paxillin displayed analogous filopodial projections (Figure 2B). This finding indicated that the process was a characteristic of NIH3T3 fibroblasts and not a feature specific to the α1-RFP-β1 integrin and its ligand collagen IV.

Figure 2.

α1-RFP integrin localization in cells spreading on its ligand collagen IV compared with fibronectin. A1R cells were allowed to spread on collagen IV or fibronectin for 15–25 min. Then, they were fixed, stained for paxillin, and examined by TIRF microscopy. (A) TIRF images of α1-RFP and paxillin 15 min after spreading on collagen IV. (B) TIRF images of α1-RFP and paxillin 15 min after spreading on fibronectin. For A1R cells spreading on fibronectin, the α1-RFP receptor was not ligand bound and served as a diffuse membrane stain. Bar, 5 μm. (A and B) Panels at right are enlargements of regions outlined in the paxillin images of the whole cell. (C) TIRF and epifluorescent images of endogenous paxillin and α1-RFP, respectively, after 25 min spreading on fibronectin. Arrows in merged image indicate where filopodial adhesions containing paxillin (green) anchor a larger membrane area (α1-RFP, red). Bar, 5 μm. α1-RFP integrin is enriched in filopodia when spreading on its ligand collagen IV, whereas on fibronectin the reporter behaves as a diffuse membrane marker surrounding the filopodial paxillin projection at early spreading time but forms a large veil spanning the filopodial paxillin projections at later times.

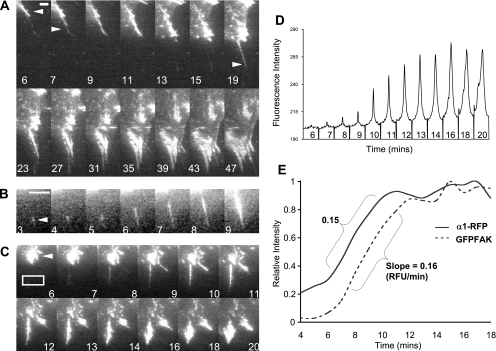

Figure 3.

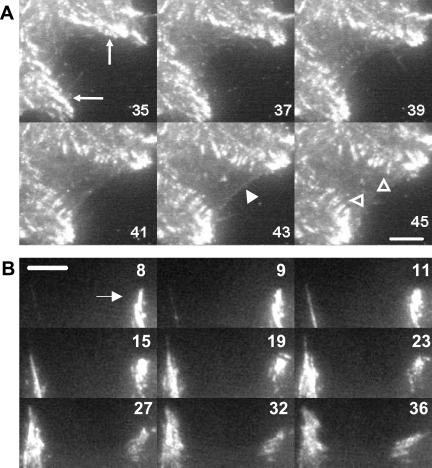

Analysis of filopodial projections. (A) A montage of a developing adhesion from an A1R cell spreading on collagen IV between 6 and 47 min after spreading began visualized by α1-RFP. Arrowheads indicate the formation of new projections. Bar, 2 μm. (B) A montage of one adhesion from a second cell. Arrowhead indicates the first point of contact of the integrin with the ECM. Cell periphery visible at top left of each frame. Bar, 2 μm. (C) A montage of an adhesion from a third cell between 6 and 20 min after spreading began visualized by GFP-FAK. Arrowhead indicates mature FA before disassembly (see Supplemental Video 2). (D) Fluorescence intensity profile of a cross-section of a developing adhesion (box in Figure 3C) from 6 to 20 min after spreading began. Maximum intensity occurred in the same pixel position in each successive frame, indicating that the projection did not move laterally during the recording. (E) Relative intensity of the peak value of GFP-FAK in comparison with α1-RFP integrin in a cross-section of a developing adhesion from 4 to 18 min after spreading began. The slope of the line (relative fluorescence units/minute) during the period where the increase in intensity is linear was almost identical for the two proteins.

α1-RFP was clearly localized to filopodia when the cells were spreading on its corresponding ligand collagen IV (Figures 1 and 2A). Furthermore, on FN, both the integrin reporter (which behaves as a diffuse membrane marker on FN) and the adapter protein paxillin were localized to projections at the membrane periphery, which indicated that at the early phases of spreading the filopodia were protruding outward from the perimeter of the cell (Figure 2B). However, we wanted to establish that on collagen IV, the α1-RFP integrin was binding ligand and therefore responsible for the initiation of adhesion, compared with FN, where the reporter was visible at filopodia purely as a membrane marker. By comparing the intensity of labeling of α1-RFP on collagen IV, its ligand, with the intensity on FN, the degree of enrichment in the filopodia could be compared. Importantly, relative to paxillin, there was a 2.3 ± 0.3-fold (n = 6 cells) increase in the average intensity of labeling by α1-RFP in filopodia when the cells were spread on collagen IV versus when they were spread on FN, indicating that on collagen IV the α1-RFP integrin was more vigorously recruited to the filopodia (Figure 2B). These results strongly suggest that the filopodia observed in cell spreading on collagen IV are sites of engagement of α1-RFP with its ligand and are the initial contact sites with the ECM during spreading.

Generation of Mature FAs from Filopodial Projections

We next investigated how these projections were transformed into mature FAs. Unexpectedly, during spreading FAs did not form through fragmentation of a leading edge and subsequent aggregation into a FA, as has been observed in migrating cells (Rottner et al., 1999). Rather, once an integrin projection was initiated, the filopodia subsequently lengthened. However, this process was not gradual; after individual projections formed, they did not extend. Instead, the newly formed projection accumulated more integrin (thus thickening and brightening) and sporadically nucleated the formation of another fine projection (Figure 3A, arrowheads). This process continued until the projections became brighter, coalesced, contracted slightly, and mature FAs were formed (Figure 3A and Supplemental Video 2). Analysis of the average intensity in a cross-section of a nascent FA confirmed that the projections became increasingly bright with time (Figure 3D). In addition, this analysis revealed that the position of the peak value in the image did not change throughout the recording. This result was significant, because it further demonstrated that these initiating adhesions were anchored to the ECM while accumulating integrin and focal adhesion components (Figure 3, C and D). Furthermore, a comparison of the accumulation of GFP-FAK to an α1-RFPβ1 integrin projection showed that the two proteins were recruited at an almost identical rate (Figure 3E). Interestingly, similar results were obtained for other adhesions comparing FAK and integrin as well as for GFP-paxillin accumulation to integrin (our unpublished data), indicating that, at least in spreading, the components of the FA are recruited to the filopodial adhesion proportionately at the same rate.

Although most integrin projections were initiated from ligand-bound contacts and were visible along the length of the filopodia (Figure 3A), some were first observed as disconnected from the cell periphery and hence not as a projection as it seemed in TIRF microscopy (Figure 3B). In subsequent frames, the center of light intensity of these adhesions then moved back toward the periphery of the cell until they could be visualized as connected to the cell (Figure 3B). The most likely explanation for this was that the projection initiated from part of the cell above the evanescent field (approx. 100 nm); consequently, it was not visible in TIRF microscopy. That part of the cell, now tethered to the ECM, was then brought down closer to the surface of the glass and into the visible field (Supplemental Figure S3). This finding was important because it suggested that the integrin-containing filopodia could act as an adhesion sensor and communicate a signal to bring the cell closer to the substratum. Thus, ligand bound integrin initiates the adhesion as a filopodia and helps bring the cell to the substratum during spreading.

As indicated, the successive formation of filopodia was a feature of FA generation. We also noted that in order for FAs to form at the cell periphery via this method, the initial filopodia, which subsequently swelled to a nascent FA, often disassembled as new filopodia were projected forward (Figure 3C and Supplemental Video 2). Thus, continual generation of filopodia and subsequent disassembly of the recently constructed adhesions seemed to be critical to the formation of mature FAs in spreading cells. However, this process, although repeated numerous times during FA generation (Figure 3A), was not infinite. Possibly due to contraction signals provided by the small GTPase Rho, activated substantially only after 30 min of spreading (Ren et al., 1999), filopodia formation ceased after 30–45 min, and more mature FAs were formed (Figures 1 and 3, A and C).

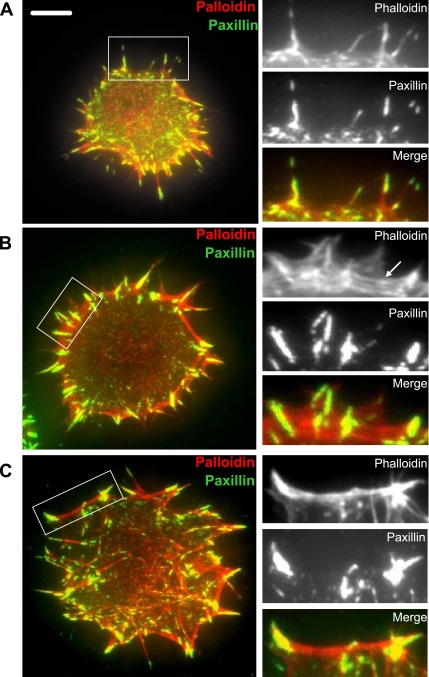

Actin Reorganization during Cell Spreading

To confirm that the integrin-containing projections that generated mature FAs were bona fide actin-containing filopodia, we fixed and stained spreading cells with phalloidin and paxillin to reveal projections in TIRF microscopy. Both F-actin and paxillin were localized in filopodia formed in the spreading cells (Figure 4A). The result was significant because it indicated that even at early points in adhesion formation, actin was localized with FA proteins, even though it had not formed cytoskeletal stress fibers.

Figure 4.

Actin localization in spreading cells. Paxillin (green) and phalloidin (red) staining of NIH3T3 cells between 15 and 30 min after spreading began on FN, as observed by TIRF microscopy. Yellow regions indicate paxillin and phalloidin colocalization. (A) After ∼15 min of spreading, filopodial projections contain both paxillin and F-actin. Bar, 10 μm. (B) After ∼23 min of spreading, F-actin forms a scaffold (arrow) between paxillin-containing filopodia at the cell's periphery. (C) After ∼30 min of spreading, nascent FAs anchor recognizable stress fibers that begin to traverse the cell. Sets of three panels to the right are enlarged views of regions outlined by boxes in images of the whole cell.

As mentioned above, dynamics of adhesion molecules indicated that the filopodia, once formed, recruited more FA proteins, but they were adherent and hence they did not themselves extend or move laterally. In analyzing cells fixed at various stages of spreading, it was evident that during this stage, after the projection of a new filopodia containing integrin and actin, the actin subsequently organized and formed a cortical cytoskeletal bridge between filopodia as more FA proteins were recruited (Figure 4B, arrow). These structures were neither filopodial nor recognizable as mature stress fibers, but they represent an intermediate stage in actin organization. These cytoskeletal structures also correlated with membrane formations at later spreading times. During this stage, while adhesions remained filamentous in form, the membrane (as seen with α1RFP as a marker) formed a large veil spanning the two filopodial paxillin peaks (Figure 2C).

In the later stages of spreading, some maturing FAs reoriented laterally to the cell centroid and subsequently contracted (Figure 5). In part, the contraction of lateral integrin anchor points facilitated extension of large folds of membrane to the substratum (Figure 5A, arrowhead, and Supplemental Video 1). More importantly, the reorientation of FAs provided cytoskeletal anchors for the strengthening of lateral actin stress fibers (Figures 4C and 5B and Supplemental Video 2). In fully spread cells, actin stress fibers are anchored by FAs some distance apart and can span the central region of the cell (Smilenov et al., 1999). In contrast, while filopodial FA precursors were assembled, early actin structures formed only between integrin-filopodia that were adjacent. At an intermediate stage, when a cell began to reorient some FAs, actin fibers began to form between more distant FAs and could traverse parts of the cell center (Figure 4C).

Figure 5.

FAs reorient laterally in the final stages of spreading. Cells stably expressing α1RFP alone (A) and coexpressing GFP-FAK (B) were allowed to spread on collagen IV. Images were captured every 60–90 s. Numbers indicate time (minutes) after spreading began. (A) The reorientation of two sets of focal adhesions laterally to the cell centroid visualized by α1-RFP. Bar, 5 μm. Arrows indicate two filopodial adhesions oriented approximately radially to the cell centroid, closed arrowhead indicates the membrane fold lowered to the substratum and brought into the evanescent field, and open arrowheads indicate the focal adhesions now oriented laterally to the cell centroid. (B) Reorientation of a maturing FA (arrowhead) in a second cell visualized by a FA protein reporter, GFP-FAK. Arrow indicates initial filopodial projected radially to the cell centroid. Reorientation likely provides anchor points for lateral actin fibers that are contracting.

Integrin and Talin Localize to Filopodial Projections before FAK and Paxillin

The generation of mature FAs requires an ordered recruitment of the proteins that comprise an established plaque. We expected that in the initiating adhesions during spreading, the transmembrane ECM receptor would bind ligand first and the cytoplasmic FA proteins would subsequently localize to the integrin. However, the order to which proteins are recruited to FAs is not well established, and it has been suggested that cytoplasmic proteins may accumulate in FAs before the integrin organizes (Laukaitis et al., 2001). Therefore, we wanted to visualize directly the order in which integrin and cytoplasmic FA proteins were localized to new projections.

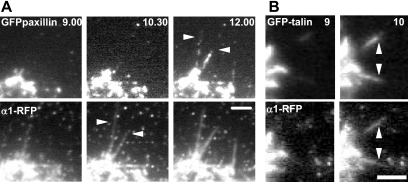

To accomplish this, we stably infected A1R cells with GFP-fusions of talin, FAK, or paxillin and examined dynamically by TIRF microscopy the colocalization of each cytoplasmic FA reporter relative to the α1-RFP-β1 integrin during spreading on collagen IV. Images of both α1-RFP and GFP-paxillin or -FAK were captured every 60–90 s, and the relative intensity of each set of pictures was equalized. Each α1-RFP image was compared with the previous frame to identify newly formed projections. New α1-RFP projections were scored and the corresponding GFP-paxillin or -FAK images were examined to determine whether colocalization to the new projections had occurred. Analysis of these images showed that there was often a delay of 60–90 s between visualization of an integrin-containing filopodia and that of both GFP-paxillin (Figure 6A and Table 1) and GFP-FAK (Table 1), scored by a reduction in the frequency of colocalization. In 24–35% of newly formed integrin projections, the filopodia were not labeled with FAK or paxillin (Table 1). In no cases did we observe projections labeled with FAK or paxillin in frames before integrin labeling. In all cases, after this delay, there was colocalization in subsequent frames (Figure 6). Thus, at least in spreading cells, adhesion sites were initiated by integrin and subsequently FAK and paxillin were recruited.

Figure 6.

Focal adhesions assemble components in a discrete order. A1R cells were allowed to spread on collagen IV. (A) GFP-paxillin exhibited a delay in colocalization to new α1-RFP projections. New α1-RFP projections that formed between 9.00 and 10.30 min after spreading began (arrowheads) do not contain GFP-paxillin. GFP-paxillin (arrowheads) has colocalized in the subsequent frame, captured 90 s later. (B) GFP-talin was rapidly recruited to new α1-RFP projections. Discrete α1-RFP projections newly formed between 9 and 10 min after spreading on collagen IV also contain GFP-talin. Arrowheads indicate newly formed projections. Bar, 2 μm.

Table 1.

Recruitment of cytoplasmic FA proteins to new integrin projections during spreading on collagen IV

| Focal adhesion protein |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Talin | FAK | Paxillin | |

| No. new α1-RFP projections | 122 | 93 | 152 |

| FA protein recruited | 120 | 74 | 99 |

| % with delayed colocalization | 2 | 24 | 35 |

Talin is an ∼270 kDa FA protein that binds to β-cytoplasmic tails of integrins (Calderwood and Ginsberg, 2003). The integrin–talin interaction is critical for receptor activation and provides a connection to the actin cytoskeleton (Jiang et al., 2003; Tadokoro et al., 2003). Therefore, we wanted to ascertain whether there was also a delay in recruitment of talin to newly formed integrin projections in spreading cells. However, in contrast to paxillin and FAK, GFP-talin colocalized to new integrin projections in the same frame almost 100% of the time (Figure 6B and Table 1).

The observation that GFP-talin was colocalized to virtually all of the newly formed α1-RFP filopodia, whereas both GFP-FAK and GFP-paxillin were frequently delayed in their colocalization to integrin projections, strongly suggested that talin was recruited to integrin before the recruitment of FAK and paxillin. However, it was important to determine whether the same hierarchy of recruitment could be observed when the cytoplasmic FA proteins were directly compared with each other. We also wanted to determine whether this finding was characteristic of the endogenous α5β1 receptor as well as the α1-RFPβ1 integrin.

Having established the presence of filopodial-adhesions on FN, analogous to the process on collagen IV, we infected NIH3T3 fibroblasts with reporter constructs of talin and FAK, or FAK and paxillin, and applied the same method to directly compare recruitment of different FA proteins to newly formed α5β1 projections. Because GFP-talin occurred in new projections with integrins, we first decided to examine the ability of RFP-FAK to localize to GFP-talin–labeled filopodia. The result was strikingly similar to the comparison of integrin and FAK. We found that there was a delay in colocalization of RFP-FAK to GFP-talin–labeled projections (29% of 103 projections showed a 60-s delay of FAK). We then compared directly GFP-FAK and RFP-paxillin and detected no delay in colocalization with each other on FN (84 projections). Thus, talin and integrin colocalized initially and subsequently, paxillin and FAK were recruited to new projections. Because the levels of expression of the constructs were similar (Supplemental Figure S4), these colocalization differences were not likely to be due to differences in the quantity of protein expressed.

FA Protein-containing Filopodia Projection in Spreading Cells Is Cdc42 Dependent

Analysis of cells fixed at early spreading times has suggested the presence of cytoplasmic adhesion proteins in protrusions similar to filopodia (Zimerman et al., 2004). Furthermore, in studies of postmitotic spreading, actin-containing retraction fibers resembling filopodia have been characterized and have been shown to facilitate spreading (Cramer and Mitchison, 1993). Interestingly, activation of one member of the Rho family of small GTPases, Cdc42, causes dramatic extension of filopodia (Nobes and Hall, 1995), suggesting that the filopodial formation observed with integrins and FA proteins during the initiation of spreading may be triggered primarily by GTP-bound Cdc42. However, it has been reported that spreading is mediated by activation of both Cdc42 and another Rho family GTPase, Rac, which promotes lamellipodia formation (Nobes and Hall, 1995; Price et al., 1998). We wanted to characterize the relative contribution of the two GTPases to the rate of spreading and to determine whether specific inactivation of Cdc42 prevented the formation of filopodia at the initiation of spreading.

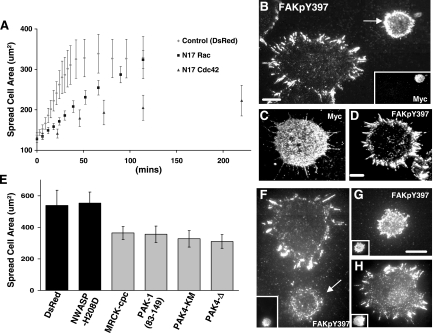

To accomplish this, we transiently cotransfected NIH3T3 cells with dominant-negative constructs of either Cdc42 or Rac (N17) and a reporter protein, DsRed, and recorded cell spreading on FN by phase-contrast microscopy. Interestingly, measurements of the two-dimensional area of the DsRed-positive cells indicated that cells cotransfected with N17Rac, although delayed in their spreading compared with cells transfected with DsRed alone, had reached normal spread cell area after ∼2 h (Figure 7A). However, cells cotransfected with N17Cdc42 did not reach normal spread cell area even after 4 h of spreading (Figure 7A). This finding indicated that although wild-type Rac activation may be important for normal kinetics of spreading, the effects of dominant-negative inhibition of this GTPase on spreading can be substantially overcome within 2 h. In contrast, inhibition of Cdc42 dramatically hindered spreading for a prolonged period.

Figure 7.

Role of small GTPases Cdc42 and Rac and their effectors in mediating the filopodial spreading phenotype. (A–D) Analysis of the effect of small GTPases Cdc42 and Rac on spreading time and filopodia projections in NIH3T3 cells. (A) Two-dimensional spread cell area measured by phase-contrast microscopy of cells transiently transfected with control plasmid (DsRed) or cotransfected with DsRed and dominant-negative N17Rac or N17Cdc42. Data are averages ± SEM of measurements taken from at least 10 cells from each of two independent experiments. (B–D) Cells transiently transfected with myc-tagged N17Cdc42 (B) or N17Rac (C and D) were trypsinized then allowed to spread on FN-coated coverslips for ∼20 min. Samples were fixed and stained for myc and FAKpY397 and examined by TIRF microscopy. (B) The cell indicated with an arrow stained positively for myc-tagged N17Cdc42 (inset), whereas cell at bottom left was untransfected. Cdc42 is required for the radial projection of filopodia containing adhesion molecules to facilitate rapid cell spreading. (E–H) The spreading behavior of 3T3 cells was examined after transient transfection with dominant-negative Cdc-42 effector constructs N-WASP-H208D, MRCK-cpc, PAK-1(83–149), PAK4-KM, and PAK4Δ, and the control plasmid DsRed and allowed to spread on fibronectin coated coverslips. (E) Two-dimensional spread cell area was measured by fixing and staining cultures after 60 min after spreading began and capturing phase-contrast images of cells positive for the transgene in epifluorescent microscopy. Data are averages ± SEM of measurements taken from at least 10 cells from each of two independent experiments. (F–H). Cells transfected with MRCK-cpc (F) or PAK4-KM (G) or N-WASP-H208D (H) were allowed to spread for 30 min and fixed and stained for the transgene (insets) and either FAKpY397 (F and G) or FAK (H) and examined by TIRF microscopy. Bar, 10 μm. (F) The cell indicated by an arrow stained positively for myc-tagged N17Cdc42 (inset), whereas the cell at top was untransfected. The Cdc42 effectors PAK1, PAK4, and MRCK (but not N-WASP) are involved in the formation of filopodia during spreading.

The profound inhibition of spreading by N17Cdc42 suggested the possibility that wild-type activity of this GTPase was required for the initiation of filopodial projections in order for cells to adhere and flatten. We wondered whether dominant-negative N17Cdc42 prevented the formation of these adhesions and thus blocked spreading at this crucial initial phase. This hypothesis was tested by staining fixed cells with an antibody for myc-tagged N17Cdc42 as well as FAKpY397, to reveal FA proteins. The N17Cdc42-transfected cells did not display FAKpY397-stained filopodia (Figure 7B), whereas N17Rac-transfected cells exhibited clearly identifiable, FAKpY397-containing, filopodial structures in the early stages of spreading (Figure 7, C and D). Together, these results strongly suggest that cell spreading can occur, albeit delayed, in the absence of Rac activation. However, under normal conditions, the process is initiated through and dramatically facilitated by Cdc42-induced, FA protein-containing filopodia.

Having established that Cdc42 was the GTPase principally responsible for the formation of filopodia during spreading, we wanted to investigate the downstream effectors that mediated the phenotype. A number of Cdc42 effectors have been implicated in cytoskeletal changes and the formation of filopodia in other contexts, such as N-WASP, mDia2, PAK4, MRCK, and PAK1 (Abo et al., 1998; Miki et al., 1998; Zhao et al., 1998; Edwards et al., 1999; Peng et al., 2003). We wanted to assess what influence these effectors had on spreading and filopodia formation. First, we eliminated mDia2 as a candidate, confirming that it is not expressed in our NIH3T3 cells (Tominaga et al., 2000; our unpublished data). To assess the other candidates, we transiently transfected into 3T3 cells the dominant-negative constructs N-WASP-H208D (which cannot bind to Cdc42), MRCKcpc (which lacks both the kinase domain and the GTPase binding domain [GBD]), PAK4-Δ (which has both the kinase and GBD domains deleted), PAK4-KM (which is kinase dead but can bind to the GBD domain), and PAK1(83-149) (comprising only the autoinhibitory regulatory domain, which inhibits PAK activity in vitro) (Abo et al., 1998; Miki et al., 1998; Zhao et al., 1998; Edwards et al., 1999) and examined spreading and filopodia formation in transfected cells.

First, we analyzed whether the dominant-negative effector constructs had an influence on the rate of spreading by measuring the spread cell area of each transfected cell compared with the area of cells transfected with DsRed. Interestingly, this analysis revealed that three of the four dominant-negative effectors tested, MRCK, PAK4, and PAK1, led to significantly decreased spreading after 60 min, albeit not as dramatically as N17Cdc42. However, dominant-negative N-WASP did not have a significant influence on spreading compared with DsRed-transfected cells (Figure 7E). We then wanted to determine whether this reduction in spreading corresponded to effects on the formation of filopodial projections at earlier spreading times. Interestingly, when examined by TIRF microscopy, cells transfected with dominant-negative MRCK, PAK4 (Figure 7, F and G), or PAK-1 (our unpublished data), had a greatly reduced ability to project filopodia after 30 min of spreading. In contrast, cells transfected with N-WASP-H208D displayed filopodia in early spreading, a phenotype characteristic of wild-type cells (Figure 7H). The published data indicating that N-WASP induces filopodia (and inhibition by the dominant-negative N-WASP-H208D) occurred in the presence of constitutively active Cdc42 (Miki et al., 1998). It is possible that in the wild-type form, where Cdc42 is in the GTP-bound state only transiently, the other effectors more effectively bind to the GBD to mediate downstream signals and filopodia formation.

The constructs that we used to test the role of these kinases would not bind to the GBD of Cdc42, so that they would not act as global inhibitors by binding to this crucial site and eliminating Cdc42 activity. However, we also used a defective PAK-4, which still could bind to Cdc42, as a global inhibitor. Those results (Figure 7) showed this construct blocked spreading and filopodial formation, reinforcing the notion that Cdc42, not Rac is critical for spreading in these cells.

Src Is Required for Rapid Actin and FA Reorganization after Early Spreading

Interestingly, analysis of the change in cell area during spreading by phase-contrast microscopy indicated that wild-type cells flattened rapidly to ∼75% of their final two-dimensional surface area within 20–25 min of adhesion beginning (Figure 7A). In contrast, after 30 min of spreading, cell flattening slowed, cells halted the sequential projection of filopodia, and subsequently, some nascent FAs reoriented and disassembled. Together, these observations suggested a two-phase spreading process: an initial, rapid flattening of the cell facilitated by the approximately symmetrical projection of filopodia, followed by a more asymmetrical spreading of the cell characterized by restructuring of nascent FAs and organization of the actin cytoskeleton into stress fibers. We were interested in understanding the mechanism by which this transition took place. Increased cytoskeletal organization (likely driven by Rho activation) was undoubtedly crucial to this process as lateral cortical actin formed between radial filopodial FA precursors before reorientation of these adhesion structures occurred. However, we wanted to know whether specific FA-related triggers were also involved.

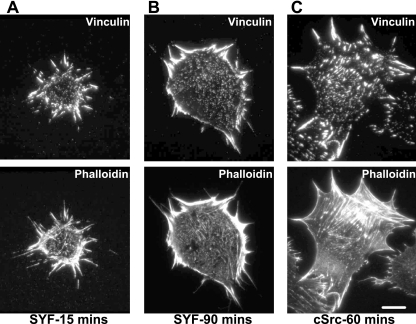

Src family kinases (SFKs) are a group of ubiquitously expressed, nonreceptor tyrosine kinases that are critical for adhesion-mediated signaling and motility. Furthermore, spreading has been reported to be delayed in SFK null fibroblasts (SYF cells) (Klinghoffer et al., 1999; Cary et al., 2002). Therefore, we examined the features of spreading of SYF cells at various times. Surprisingly, in the initial stages of spreading, SYF cells displayed the characteristic radial-filopodial adhesion structures similar to NIH3T3 cells (Figure 8A). This result indicated that, unlike Cdc42, Src was not required for the initial filopodial phase of the spreading process.

Figure 8.

Src promotes actin reorganization in later spreading. SYF cells (A and B) and cells re-expressing cSrc (C) were allowed to spread for 15–90 min on FN-coated coverslips, fixed, and stained with phalloidin for F-actin or vinculin for FAs. Bar, 10 μm. SYF cells could spread substantially by projection of FA protein-containing filopodia but the actin persisted in a radial pattern for an extended period compared with cSrc-reexpressing cells.

In fully spread SYF cells, phosphotyrosine levels are very low (Klinghoffer et al., 1999), and we wanted to determine whether this diminished signaling capacity would hinder the rapid reorganization of FAs and actin in the later phase of spreading. Interestingly, when SYF cells were allowed to spread on FN, radial FA projections anchoring cortical actin structures between adjacent adhesions persisted for up to 90 min (Figure 8B). Hence, although SYF cells were substantially spread after 60–90 min, the cells remained with radial distributed actin. In contrast, Src-reexpressing SYF cells behaved similarly to NIH3T3 cells and developed actin stress fibers after ∼60 min of spreading (Figure 8C). This finding indicated that the dynamic changes in cytoskeletal and FA structures that occurred in wild-type cells between 30 and 60 min after spreading began were delayed in the absence of SFKs, suggesting that signaling capacity of Src was important for generation of mature actin stress fibers in spreading.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that in routine culture conditions, fibroblast spreading is facilitated by the continuous and sequential generation of filopodial structures containing integrins and FA proteins. Importantly, ligand-bound integrins are the initial adhesive sites in these filopodia, because they are enriched in the projections compared with the surrounding membrane, and they provide stationary contacts during the early stages of spreading. In addition, we have demonstrated that spreading proceeds via a hierarchical assembly of focal adhesion components into the filopodia. Finally, we have shown that as the filopodia thicken and accumulate focal adhesion components, these adhesive contacts progress to form mature focal adhesions that anchor actin stress fibers. These results are novel, because integrin-mediated filopodial spreading has not been characterized previously nor has the concept that these filopodia are a precursor to focal adhesions in spreading.

The involvement of actin in FA generation is critically important. First, integrin-containing projections that mediate the cell's initial contact with the ECM contain F-actin and are likely generated in part by its rapid polymerization. Actin then organizes around these nascent FAs to form a cortical bridge structure connecting them. Finally, mature stress fibers are generated between reorienting adhesions. This is important because it defines the progression from filopodia to mature stress fiber via an intermediate actin structure that forms at the perimeter of the cell anchored by approximately symmetrical filopodial adhesions.

The fact that adhesion was initiated by discrete projections and that the cytoplasmic FA proteins colocalized to the filopodia allowed direct visualization of the order of recruitment of cytoplasmic FA proteins to integrin and analysis of the relative rate at which they accumulate. It has been proposed that the integrin–ligand interaction is required before the hierarchical recruitment of FA proteins to nascent adhesions (Miyamoto et al., 1995), and the finding that talin–integrin association occurred before recruitment of paxillin or FAK is consistent with indirect evidence indicating that talin, which has been shown to affect an integrins' affinity-state for ligand (Tadokoro et al., 2003), forms a crucial initial connection to integrins (Jiang et al., 2003). These results are distinct from antibody-clustering experiments, indicating that FAK can interact with the receptor without talin (Miyamoto et al., 1995). Furthermore, our results indicating that in spreading, FA proteins and integrin are recruited to developing filopodial adhesions at the same rate is in contrast to evidence suggesting that paxillin accumulation precedes integrin organization in mature FAs (Laukaitis et al., 2001).

The generation of new adhesions is essential for cell motility and spreading (Yeo et al., 2006). However, at the tail of a migrating cell, focal adhesions must disassemble in order for the cell to advance. Conceptually, a spreading cell would need to assemble new FAs, not disassemble existing FAs. However, the analysis here indicates that bona fide disassembly of FAs not only occurs but also may be critical to the ability of the cell to extend FAs to its periphery during spreading. Interestingly, the finding that initial adhesion sites were nonmotile, whereas more mature FAs could reorient, was in agreement with a proposed mechanism for modulating the connection between the receptor and the cytoskeleton to regulate propulsive forces in migrating cells (Smilenov et al., 1999; Beningo et al., 2001).

Our data indicated that in spreading cells, Cdc42 triggered the projection of integrin-containing filopodia that are adhesion precursors and provide the initial contact with the substratum. Given that the dramatic filopodia formations were continually renewed throughout the spreading process, we anticipated that more than one Cdc42 effector may be involved in this process. When we screened four effectors implicated in filopodial formation in other contexts, we found that PAK1, PAK4, and MRCK (but not N-WASP) had an effect on the formation of filopodia during spreading. These kinases all play a role in connecting Cdc42 to downstream kinases that are involved in actin cytoskeletal dynamics. These results show that these filopodia share similarities to those examined in other conditions, such as those studied by overexpression of activated Cdc42 or its effectors (Nobes and Hall, 1995; Miki et al., 1998).

It is important to note that FA formation from filopodia was observed in nonstarved cells permitted to settle on ECM-coated glass in normal growth media. Others have used different conditions, including serum starvation and synchronization of attachment by centrifugation, which resulted in lamellipodial-based spreading (Giannone et al., 2004). Under our conditions, most cells generated FA from filopodial projections, whether spreading on FN using endogenous receptors or on collagen IV using the α1-RFP integrin. We now have shown that these filopodia are the initial contacts with the ECM and proceed to generate mature FAs through a coherent and sequential mechanism. This observation has important implications for the formation of FAs in other contexts, such as cell migration and postmitotic cell spreading. Using the methods described here for analyzing the initiation of adhesion sites, the hierarchy of assembly of other important focal adhesion proteins, such as phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase type 1γ (Di Paolo et al., 2002), can be tested. Furthermore, the role of cell signaling in the formation of focal adhesions in spreading cells can now be fully investigated. For example, the targets for Src-induced actin reorganization can also be deduced. Last, myosin X has been proposed as a motor in filopodia, which is integrin dependent (Zhang et al., 2004), and it will be important to determine the specific role of this motor in early cell spreading.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank L. Hughes for technical assistance; G. Gundersen for critical review of the manuscript; and J. Schmoranzer, E. Gomes, and E. Ezratty for microscopy assistance and discussions. We also thank A. Minden, G. Bokoch, S. Greenberg, S. Suetsugu, R. Tsien, C. Turner, H. Varmus, and K. Yamada for their generous gifts of constructs. TIRF microscope setup was provided by National Institutes of Health Grant 1S10RR017911.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0496) on July 19, 2006.

REFERENCES

- Abo A., Qu J., Cammarano M. S., Dan C., Fritsch A., Baud V., Belisle B., Minden A. PAK4, a novel effector for Cdc42Hs, is implicated in the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton and in the formation of filopodia. EMBO J. 1998;17:6527–6540. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beningo K. A., Dembo M., Kaverina I., Small J. V., Wang Y. L. Nascent focal adhesions are responsible for the generation of strong propulsive forces in migrating fibroblasts. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:881–888. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briesewitz R., Epstein M. R., Marcantonio E. E. Expression of native and truncated forms of the human integrin alpha 1 subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:2989–2996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderwood D. A., Ginsberg M. H. Talin forges the links between integrins and actin. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:694–697. doi: 10.1038/ncb0803-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R. E., Tour O., Palmer A. E., Steinbach P. A., Baird G. S., Zacharias D. A., Tsien R. Y. A monomeric red fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:7877–7882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082243699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary L. A., Klinghoffer R. A., Sachsenmaier C., Cooper J. A. SRC catalytic but not scaffolding function is needed for integrin-regulated tyrosine phosphorylation, cell migration, and cell spreading. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:2427–2440. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.8.2427-2440.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer L., Mitchison T. J. Moving and stationary actin filaments are involved in spreading of postmitotic PtK2 cells. J. Cell Biol. 1993;122:833–843. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.4.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Pozo M. A., Price L. S., Alderson N. B., Ren X. D., Schwartz M. A. Adhesion to the extracellular matrix regulates the coupling of the small GTPase Rac to its effector PAK. EMBO J. 2000;19:2008–2014. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.9.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo G., Pellegrini L., Letinic K., Cestra G., Zoncu R., Voronov S., Chang S., Guo J., Wenk M. R., De Camilli P. Recruitment and regulation of phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase type 1 gamma by the FERM domain of talin. Nature. 2002;420:85–89. doi: 10.1038/nature01147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards D. C., Sanders L. C., Bokoch G. M., Gill G. N. Activation of LIM-kinase by Pak1 couples Rac/Cdc42 GTPase signalling to actin cytoskeletal dynamics. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1:253–259. doi: 10.1038/12963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezratty E. J., Partridge M. A., Gundersen G. G. Microtubule-induced focal adhesion disassembly is mediated by dynamin and focal adhesion kinase. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:581–590. doi: 10.1038/ncb1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannone G., Dubin-Thaler B. J., Dobereiner H. G., Kieffer N., Bresnick A. R., Sheetz M. P. Periodic lamellipodial contractions correlate with rearward actin waves. Cell. 2004;116:431–443. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes R. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang G., Giannone G., Critchley D. R., Fukumoto E., Sheetz M. P. Two-piconewton slip bond between fibronectin and the cytoskeleton depends on talin. Nature. 2003;424:334–337. doi: 10.1038/nature01805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinghoffer R. A., Sachsenmaier C., Cooper J. A., Soriano P. Src family kinases are required for integrin but not PDGFR signal transduction. EMBO J. 1999;18:2459–2471. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laukaitis C. M., Webb D. J., Donais K., Horwitz A. F. Differential dynamics of alpha 5 integrin, paxillin, and alpha-actinin during formation and disassembly of adhesions in migrating cells. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:1427–1440. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.7.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki H., Sasaki T., Takai Y., Takenawa T. Induction of filopodium formation by a WASP-related actin-depolymerizing protein N-WASP. Nature. 1998;391:93–96. doi: 10.1038/34208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra S. K., Hanson D. A., Schlaepfer D. D. Focal adhesion kinase: in command and control of cell motility. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrm1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S., Akiyama S. K., Yamada K. M. Synergistic roles for receptor occupancy and aggregation in integrin transmembrane function. Science. 1995;267:883–885. doi: 10.1126/science.7846531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobes C. D., Hall A. Rho, rac, and cdc42 GTPases regulate the assembly of multimolecular focal complexes associated with actin stress fibers, lamellipodia, and filopodia. Cell. 1995;81:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90370-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo A. F., Eng C. H., Schlaepfer D. D., Marcantonio E. E., Gundersen G. G. Localized stabilization of microtubules by integrin- and FAK-facilitated Rho signaling. Science. 2004;303:836–839. doi: 10.1126/science.1091325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pear W. S., Nolan G. P., Scott M. L., Baltimore D. Production of high-titer helper-free retroviruses by transient transfection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:8392–8396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J., Wallar B. J., Flanders A., Swiatek P. J., Alberts A. S. Disruption of the Diaphanous-related formin Drf1 gene encoding mDia1 reveals a role for Drf3 as an effector for Cdc42. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:534–545. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price L. S., Leng J., Schwartz M. A., Bokoch G. M. Activation of Rac and Cdc42 by integrins mediates cell spreading. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1998;9:1863–1871. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.7.1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X. D., Kiosses W. B., Schwartz M. A. Regulation of the small GTP-binding protein Rho by cell adhesion and the cytoskeleton. EMBO J. 1999;18:578–585. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottner K., Hall A., Small J. V. Interplay between Rac and Rho in the control of substrate contact dynamics. Curr. Biol. 1999;9:640–648. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80286-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastry S. K., Burridge K. Focal adhesions: a nexus for intracellular signaling and cytoskeletal dynamics. Exp. Cell Res. 2000;261:25–36. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smilenov L. B., Mikhailov A., Pelham R. J., Marcantonio E. E., Gundersen G. G. Focal adhesion motility revealed in stationary fibroblasts. Science. 1999;286:1172–1174. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadokoro S., Shattil S. J., Eto K., Tai V., Liddington R. C., de Pereda J. M., Ginsberg M. H., Calderwood D. A. Talin binding to integrin beta tails: a final common step in integrin activation. Science. 2003;302:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.1086652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga T., Sahai E., Chardin P., McCormick F., Courtneidge S. A., Alberts A. S. Diaphanous-related formins bridge Rho GTPase and Src tyrosine kinase signaling. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80399-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomre D., Manstein D. J. Lighting up the cell surface with evanescent wave microscopy. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:298–303. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02027-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner C. E. Paxillin and focal adhesion signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:E231–E236. doi: 10.1038/35046659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch M. D., Mullins R. D. Cellular control of actin nucleation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2002;18:247–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.040202.112133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo M. G., Partridge M. A., Ezratty E. J., Shen Q., Gundersen G. G, Marcantonio E. E. Src SH2 arginine 175 is required for cell motility: specific FAK targeting and focal adhesion assembly function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:4399–4409. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01147-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Berg J. S., Li Z., Wang Y., Lang P., Sousa A. D., Bhaskar A., Cheney R. E., Stromblad S. Myosin-X provides a motor-based link between integrins and the cytoskeleton. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:523–531. doi: 10.1038/ncb1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z. S., Manser E., Chen X. Q., Chong C., Leung T., Lim L. A conserved negative regulatory region in alphaPAK: inhibition of PAK kinases reveals their morphological roles downstream of Cdc42 and Rac1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:2153–2163. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimerman B., Volberg T., Geiger B. Early molecular events in the assembly of the focal adhesion-stress fiber complex during fibroblast spreading. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 2004;58:143–159. doi: 10.1002/cm.20005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.