Abstract

The fission yeast multiprotein-component Sim4 complex plays a fundamental role in the assembly of a functional kinetochore. It affects centromere association of the histone H3 variant CENP-A as well as kinetochore association of the DASH complex. Here, multicopy suppressor analysis of a mutant version of the Sim4 complex component Mal2 identified the essential Fta2 kinetochore protein, which is required for bipolar chromosome attachment. Kinetochore localization of Mal2 and Fta2 depends on each other, and overexpression of one protein can rescue the phenotype of the mutant version of the other protein. fta2 mal2 double mutants were inviable, implying that the two proteins have an overlapping function. This close interaction with Fta2 is not shared by other Sim4 complex components, indicating the existence of functional subgroups within this complex. The Sim4 complex seems to be assembled in a hierarchical way, because Fta2 is localized correctly in a sim4 mutant. However, Fta2 kinetochore localization is reduced in a spc7 mutant. Spc7, a suppressor of the EB1 family member Mal3, is part of the conserved Ndc80–MIND–Spc7 kinetochore complex.

INTRODUCTION

The segregation of the duplicated sister chromatids into two equal sets is achieved by the interaction between spindle microtubules and chromosomes. Attachment of the mitotic spindle fibers occurs at the kinetochore, a multicomponent organelle assembled on centromeric DNA. Kinetochores perform various functions during mitosis: they mediate attachment of the sister chromatids with the plus-ends of spindle microtubules and maintain microtubule attachment during dynamic microtubule behavior, thus generating the physical forces required for chromosome movement. In addition, this complex is needed for spindle checkpoint signaling that regulates anaphase onset. These functions can be carried out by essentially all types of kinetochores, although the centromeric DNA requirements and the composition of the various protein kinetochore complexes can vary greatly between different organisms (Pidoux and Allshire, 2000; Cleveland et al., 2003).

The simplest kinetochore seems to be that of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which consists of 125-base pair centromeric DNA and >60 kinetochore proteins organized into discrete complexes (De Wulf et al., 2003; McAinsh et al., 2003; Westermann et al., 2003). Budding yeast kinetochores exist during most of the cell cycle, and the proteins of this organelle are organized into multiple functional subcomplexes that are assembled hierarchically. The outer part of the budding yeast kinetochore associates with a single spindle microtubule (Winey et al., 1995).

Kinetochores from higher eucaryotes, in contrast, can encompass megabases of highly repetitive DNA sequences, they are predicted to contain >100 proteins, and they are assembled from S phase to early mitosis (Fukagawa, 2004; Maiato et al., 2004). The association of ∼20 microtubule plus-ends to the outer plate of a vertebrate kinetochore requires correct orientation of the microtubule attachment sites to one pole to avoid merotelic attachments.

The kinetochores of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe lie in between these two extremes. The centromeric DNA of S. pombe is 35–100 kb and is composed of a central core region that is flanked by inner and outer repetitive sequences. Marker genes that are placed within the centromeric DNA are transcriptionally silenced (Allshire et al., 1994, 1995). S. pombe kinetochore proteins identified to date either associate with the central domain or with the heterochromatic outer repeats, thus enforcing the existence of two distinct domains in the fission yeast centromeres. Although the outer repeats play an important role in sister centromere cohesion and possibly help to properly orient the multiple kinetochore microtubule attachment sites (Pidoux and Allshire, 2004), the central region is needed for the assembly of the kinetochore per se and the interaction with the mitotic spindle fibers (Saitoh et al., 1997; Goshima et al., 1999; Jin et al., 2002; Pidoux et al., 2003; Kerres et al., 2004; Obuse et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2005; Sanchez-Perez et al., 2005). The central region has a distinct composition as evidenced by the association of the conserved histone H3 variant Cnp1 and shows an unusual chromatin structure, because a limited micrococcal nuclease digestion gives rise to a smear instead of the expected nucleosomal ladder (Polizzi and Clarke, 1991; Takahashi et al., 1992, 2000). Kinetochore proteins that associate with the central region are required to maintain this specialized chromatin structure (Saitoh et al., 1997; Goshima et al., 1999; Jin et al., 2002). A substantial number of proteins that associate constitutively with the central region have been described, and mutations in genes coding for these proteins lead to extreme missegregation of chromosomes (Saitoh et al., 1997; Goshima et al., 1999; Jin et al., 2002; Pidoux et al., 2003; Hayashi et al., 2004). Recently, using affinity purification, the majority of these proteins have been grouped into two biochemically separable complexes, namely, the Ndc80–MIND–Spc7 and the Sim4 complexes (Liu et al., 2005). The MIND complex, made up of four conserved, essential proteins, serves in budding yeast as a bridge between kinetochore subunits that associate with the centromeric DNA and those that bind microtubules (De Wulf et al., 2003; Obuse et al., 2004). The four component Ndc80 complex is also conserved from yeast to human and is required for kinetochore–microtubule association and spindle checkpoint signaling (He et al., 2001; Janke et al., 2001; Wigge and Kilmartin, 2001). Finally, the Spc7 protein was identified as an interaction partner of the Mal3 protein, a member of the EB1 family of microtubule plus-end–binding proteins (Kerres et al., 2004). Its Caenorhabditis elegans homologue KNL-1 is required for targeting a number of components of the outer kinetochore, thus directing the assembly of the microtubule–kinetochore interface (Desai et al., 2003). Proteins of the Ndc80–MIND–Spc7 complex have been shown to be required for the special chromatin structure of the central centromere region; however, they do not seem to be required for the association of the kinetochore-specific histone H3 variant Cnp1 with this region (Goshima et al., 1999; Takahashi et al., 2000; Hayashi et al., 2004). This is in contrast to Sim4 complex components, which affect the chromatin structure and incorporation of Cnp1 (Takahashi et al., 2000; Pidoux et al., 2003). The Sim4 complex consists of 13 proteins: the previously identified Sim4, Mis6, Mal2, Mis15, and Mis17 proteins as well as the newly identified Fta1-7 proteins and Dad1, a component of the DASH complex (Saitoh et al., 1997; Jin et al., 2002; Pidoux et al., 2003; Hayashi et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2005; Sanchez-Perez et al., 2005). Interestingly, one of the functions of the Sim4 complex is to act as a loading dock for the transient association of the nonessential fission yeast DASH complex with the kinetochore. It thus plays a role in chromosome biorientation (Liu et al., 2005; Sanchez-Perez et al., 2005). To better understand the function of the Sim4 complex in mitosis, we conducted a screen for extragenic suppressors of one of its members, namely, the Mal2 protein (Fleig et al., 1996; Jin et al., 2002). Mal2 is a conserved kinetochore component that is essential for faithful chromosome segregation. Its budding yeast counterpart, the Mcm21 protein, is part of the four-component COMA complex, that links DNA-associated kinetochore subcomplexes with those associating with microtubules (Ortiz et al., 1999; De Wulf et al., 2003). However, the other members of the COMA complex do not seem to exist in fission yeast. Recently, orthologues of Mal2 have been identified by computational approaches in a large number of eucaryotes (Meraldi et al., 2006). Furthermore, the human Mal2 homologue CENP-O was isolated in screens that identified proteins associated with centromeric chromatin, pointing to the importance of this protein in kinetochore function (Foltz et al., 2006; Okada et al., 2006) In this study, we identified Fta2 as a close interaction partner of Mal2 and provide evidence that the Sim4 complex seems to be assembled in a hierarchical way.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Media

Yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. New strains were obtained by crossing the appropriate strains followed by tetrad or random spore analysis and genotyping. At least three double mutants were tested per cross. Strains were grown in rich media (YE5S) or minimal media (EMM or MM) with the required supplements (Moreno et al., 1991). MM with 5 μg/ml thiamine repressed the nmt promoters. For high-level expression from nmt promoters, cells were grown in thiamine-less media for 22–24 h at 25°C or for 18–20 h at 30°C. Resistance to G418 was tested on YE5S plates containing 100 mg/l G418. Transcriptional silencing assays were carried out as described previously (Jin et al., 2002; Pidoux et al., 2003).

Table 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Name | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| UFY819 | h+fta2+/ura4+his3Δ leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 | This study |

| UFY547 | h−mal2-1-GFP/KanR leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4-D18 | This study |

| UFY518 | h− fta2-GFP/KanR leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4-D6 | This study |

| UFY544 | h− fta2-GFP/KanR mal2-1 leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4-D18 | This study |

| UFY1215 | h+fta2-292/his3+cnt1(NcoI):arg3+cnt3(NcoI):ade6+otr2(HindIII):ura4+leu1-32 ura4-D18 arg3− ade6-M210 | This study |

| UFY1189 | h− fta2-292/his3+imr1R(NcoI):ura4+ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4− | This study |

| UFY1048 | h−fta2-291/his3+his3− leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 | This study |

| UFY1050 | h− fta2-292/his3+his3− leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 | This study |

| UFY1144 | h+fta2-291/his3+his7+::lacI-GFP lys1+::LacOP ura4− leu1-32 | This study |

| UFY1179 | h+fta2-291/his3+mad2Δ::ura4+ura4-D18 ade6-M210 leu1-32 | This study |

| UFY1180 | h+fta2-291/his3+mph1Δ::ura4+ura4-D18 ade6-M210 leu1-32 | This study |

| UFY1124 | h− fta2-292/his3+mal2-GFP/KanR ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4−his3− | This study |

| UFY787 | h−fta2-HA/KanR his3-D1 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| UFY789 | h+fta2-HA/KanR mal2-GFP/KanR ura4− leu1-32 ade6-M210 | This study |

| UFY1202 | h+fta2-291/his3+mis15-68 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| UFY1204 | h− fta2-292/his3+mis15-68 leu1-32 | This study |

| UFY1198 | h− fta2-291/his3+mis6-302 leu1-32 ade6-M210 | This study |

| UFY1200 | h+fta2-292/his3+mis6-302 leu1-32 | This study |

| UFY1219 | h+fta2-291/his3+sim4-193 leu1-32 his3-D1 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 | This study |

| UFY886 | h+fta2-GFP/KanR sim4-193 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4− | This study |

| UFY889 | h− fta2-GFP/KanR mis6-302 leu1-32 | This study |

| UFY1131 | h+fta2-GFP/KanR mis15-68 leu1-32 | This study |

| UFY1129 | h− fta2-GFP/KanR mis17-362 leu1-32 ura4-D6 | This study |

| UFY1211 | h− fta2-291/his3+sim4-GFP/KanR his3-D1 leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4− | This study |

| UFY1239 | h− fta2-291/his3+mis6-3HA::leu+ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4− | This study |

| UFY1054 | h− fta2-292/his3+dad1-GFP/KanR leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 | This study |

| UFY885 | h+fta2-GFP/KanR mis12-537 leu1-32 ade6-M210 | This study |

| UFY1184 | h+fta2-GFP/KanR nuf2-1::ura4+ura4− leu1-32 | This study |

| UFY1028 | h+spc7-23/his3+his3-D1 ade6-M216 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| UFY1170 | h+fta2-GFP/KanR spc7-23/his3+leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4− | This study |

| UFY1237 | h− fta2-291/his3+spc7-GFP/KanR ade6-M210 ura4− | This study |

| UFY1085 | h− fta2-291/his3+spc7-23/his3+leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| UFY852 | h− mal2-1 leu1-32 ade6-M210 ura4-D18 | U. Fleig |

| UFY597 | h+mal2-GFP/KanR ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D6 | U. Fleig |

| FY3027 | h+cnt1(NcoI):arg3 cnt3(NcoI):ade6 otr2(HindIII):ura4 tel1L:his3 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 arg3-D4 his3-D1 | R. Allshire |

| FY4540 | h− sim4-193 cnt1(NcoI):arg3 cnt3(NcoI):ade6 otr2(HindIII):ura4 tel1L:his3 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 arg3-D4 his3-D1 | R. Allshire |

| FY5231 | h+sim4-193 arg3-D4 ade6-M210 his3-D1 ura4-D18 leu1-32 | R. Allshire |

| KG425 | h− ade6-M210 leu1-32 his3Δ ura4-D18 | K. Gould |

| KG554 | h+ade6-M216 leu1-32 his3Δ ura4-D18 | K. Gould |

| ANF251-9A | h+nuf2-1::ura4+ura4-D18 | Y. Hiraoka |

| SS638 | h− mad2Δ::ura4+leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 | S. Sazer |

| SS560 | h− mph1Δ::ura4+leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M216 | S. Sazer |

| h− mis6-302 leu1-32 | M. Yanagida | |

| h− mis15-68 | M. Yanagida | |

| h− mis17-362 | M. Yanagida | |

| h− mis12-537 leu1-32 | M. Yanagida |

Identification of fta2+ and DNA Methods

Multicopy extragenic suppressors of the mal2-1 temperature-sensitive (ts) phenotype were isolated by transformation of this strain with a genomic S. pombe DNA bank (Barbet et al., 1992). Ura+ transformants were isolated at 30.5°C to 32°C, and the genomic DNA inserts of the plasmids were sequenced. At 32°C, only wild-type mal2+ could be isolated. At 30.5°C, 4/15,000 transformants showed better growth. The plasmids of transformants able to grow better at 30.5°C but not at higher temperatures were analyzed further. One plasmid that contained four open reading frames (ORFs) (cosmid c1783 position, 739-6205) was subcloned to determine which ORF suppressed the mal2-1 ts phenotype. This identified the ORF with the systematic name SPAC1783.03, which has recently be named fta2+ (Liu et al., 2005).

A fta2+ null allele (Δfta2+) was generated by replacing the entire 1056 base pairs of the fta2+ ORF plus seven base pairs of the 3′ noncoding region with the Kanamycin-resistance (KanR) cassette in diploid strain KG425 × KG554 (Bahler et al., 1998). Tetrad analysis of 77 heterozygous Δfta2+/fta2+ diploids revealed that only the two kanamycin-sensitive (KanS) spores/tetrad grew. We attempted to delete the mal2+ ORF in haploid strain KG425 overexpressing fta2+ from the nmt1+ promoter as described previously (Fleig et al., 1996). We generated endogenous fta2+-gfp, fta2+-HA, mal2-1-gfp fusions via polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based gene targeting by using the KanR cassette (Bahler et al., 1998). The correct KanR transformants were indistinguishable in phenotype from the isogenic parental strain.

Generation of fta2ts Alleles

A pBSK-based plasmid containing the entire 1056-base pair-long fta2+ ORF followed 3′ by the his3+ gene was used as a template for a mutagenic PCR reaction that amplified the 3256-base pair-long fta2+ his3+ DNA fragment. This fragment was transformed in strain UFY 819, which contained the ura4+ marker placed behind the genomic fta2+ gene. His+ transformants that grew at 25°C but not at 36°C were identified and tested for loss of the ura4+ marker on 5-fluoroorotic acid. Correct integration of the mutagenized DNA fragments was tested via PCR. A fta2+ containing plasmid was able to fully rescue the temperature sensitivity of these mutant strains, which were backcrossed twice.

Immunoprecipitations

Chromatin immunoprecipitations (ChIP) were performed as described previously (Pidoux et al., 2003; Kerres et al., 2004). We performed at least three independent ChIP analyses per strain and temperature.

For coimmunoprecipitation, Fta2-HA–, Mal2-GFP–, and Fta2-HA Mal2-GFP–expressing strains were grown at 30°C in YE5S over night followed by protein extraction and immunoprecipitation as has been described previously (Kerres et al., 2004). Eluates were boiled and resolved on a SDS-9% polyacrylamide gel and blotted. Blots were probed with anti-hemagglutinin (HA) antibody (monoclonal mouse; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim. Germany) followed by the secondary antibody (peroxidase-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-mouse IgG [H+L]; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Immobilized antigens were detected using the ECL Advance Western blotting kit (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom).

Microscopy

Photomicrographs were obtained with a Zeiss Axiovert200 fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) coupled to a charge-coupled device camera (Orca-ER; Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ) and Openlab imaging software (Improvision, Coventry, United Kingdom). Immunofluorescence microscopy was done as described previously (Hagan and Hyams, 1988; Bridge et al., 1998). Tubulin was stained using monoclonal anti-TAT1 antibodies followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). HA or green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion proteins were observed in fixed cells by indirect immunofluorescence with mouse anti-HA antibody (Covance, Princeton, NJ) or rabbit anti-GFP antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), respectively. Cy3-conjugated sheep anti-mouse antibodies or Cy3-conjugated sheep anti-rabbit antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich) were used as secondary antibodies. Cells were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) before mounting.

RESULTS

Identification of fta2+ as a Suppressor of the mal2-1 ts Mutant Phenotype

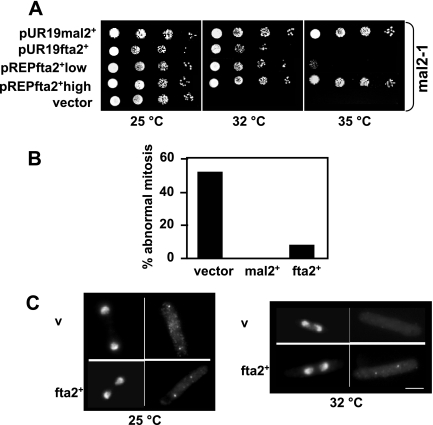

The conditionally lethal ts mal2-1 allele leads to severe missegregation of endogenous chromosomes at the restrictive temperature (Fleig et al., 1996; Jin et al., 2002). To identify Mal2 interaction partners, we conducted a multicopy extragenic suppressor screen and identified an ORF with the systematic name SPAC1783.03 that was able to suppress the temperature sensitivity of the mal2-1 strain (see Materials and Methods; Figure 1A). SPAC1783.03 codes for a 40.5-kDa protein that shows no strong sequence similarity to other proteins in the databases (Sanger Institute, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Recently, this ORF was named fta2+ (Liu et al., 2005). fta2+ driven by its own promoter on plasmid pUR19 rescued the ts phenotype of the mal2-1 strain up to 32°C, whereas overexpression of fta2+ from the repressible, wild-type nmt1+ promoter resulted in suppression of the mal2-1 nongrowth phenotype at all temperatures tested (Figure 1A). We next tested whether the essential mal2+ ORF could be replaced by high level fta2+ expression. To this end we attempted, but failed, to delete the mal2+ ORF in haploid strains strongly overexpressing fta2+ (see Materials and Methods).

Figure 1.

fta2+ suppresses the phenotypes of the mal2-1 mutant strain. (A) The rescue of the mal2-1 ts phenotype by fta2+ is dosage dependent. Serial dilution patch tests (104 to 101 cells) of mal2-1 transformants grown under selective conditions at the indicated temperatures for 4–6 d. Vector control indicates plasmid without insert; pUR19mal2+ and pUR19fta2+ denotes the presence of wild-type mal2+ or fta2+ expressed by their endogenous promoters on plasmid pUR19. pREPfta2+low and pREPfta2+high denote presence of wild-type fta2+ driven by the nmt1 promoter under repressed (low) or derepressed (high) conditions, respectively. (B) Overexpression of fta2+ suppresses mitotic defects in mal2-1 cells. The number of abnormal mitosis was determined in mal2-1 cells transformed with a vector control or plasmids expressing wild-type mal2+ or fta2+. Cells were shifted from 25 to 32°C for 6 h, fixed, and the number of aberrant anaphases was determined. N/strain = 50. (C) Kinetochore localization of Mal2-1-GFP is dependent on fta2+ overexpression. mal2-1-gfp cells transformed with vector control (v) or a plasmid expressing fta2+ under the control of the nmt1+ promoter were grown at 25 or 36°C for 6 h, and the localization of Mal2-1-GFP was determined. Bar, 5 μm.

The suppression of the mal2-1 ts phenotype by fta2+ is due to suppression of the chromosome missegregation observed in mal2-1 cells; 53.5% of mal2-1 anaphase cells transformed with a vector control and incubated at the nonpermissive temperature for 6 h showed severe chromosome segregation defects. This phenotype was fully suppressed by the presence of wild-type mal2+ on a plasmid and reduced to 9.2% in mal2-1 cells expressing extra fta2+ (Figure 1B).

As shown by the immunofluorescence analysis of a Mal2-1-GFP fusion protein, the mutant Mal2-1 protein is present at the kinetochore at 25°C. However, Mal2-1 kinetochore association is not observed at the restrictive temperature (Figure 1C). Overexpression of fta2+ in this strain rescues this phenotype, because Mal2-1-GFP shows kinetochore association at the restrictive temperature in the presence of extra fta2+ (Figure 1C). We conclude that extra fta2+ is able to rescue the mal2-1 strain by stabilizing the mutant Mal2-1 protein and/or by helping the mutant Mal2-1 protein to associate with the kinetochore at the nonpermissive temperature.

Association of the Essential Fta2 Protein with the Kinetochore Is Dependent on the Presence of Functional Mal2

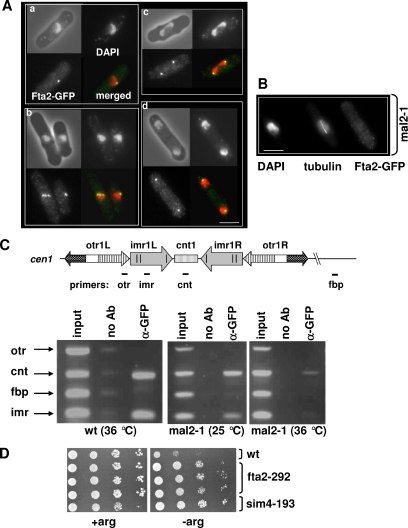

To determine whether fta2+ was essential for vegetative growth one copy of the fta2+ ORF was replaced with the KanR (kanamycin resistance) marker in a diploid strain (see Materials and Methods). Sporulation followed by tetrad analysis of 77 tetrads of this strain revealed that only two of the four spores in a tetrad could grow, and these were kanamycin sensitive, indicating that fta2+ is an essential gene. To determine the subcellular localization of Fta2, a fluorescence-improved version of GFP was fused to the COOH-terminal end of the endogenous fta2+ ORF (see Materials and Methods). Immunofluorescence of interphase and mitotic cells revealed a localization pattern characteristic of S. pombe kinetochore proteins, namely, a single fluorescent dot near the nuclear periphery in interphase and late mitotic cells and up to six fluorescent dots in metaphase cells (Figure 2A) (Jin et al., 2002). This localization pattern is dependent on the presence of a functional Mal2 protein, because no specific Fta2-GFP signal could be detected in a mal2-1 strain incubated at the restrictive temperature (Figure 2B). Fta2 protein levels in the cell were not affected in the mal2-1 strain (Supplemental Figure 1). To identify the centromere region with which Fta2 associates and to determine whether the association of Fta2-GFP with centromeric DNA was dependent on Mal2, ChIP was carried out (Partridge et al., 2000). Wild-type or mal2-1 cells expressing Fta2-GFP were analyzed in ChIP assays by using anti-GFP antibodies. The DNA present in crude extracts or in the immunoprecipitates was analyzed by multiplex PCR analysis using primers to amplify the cnt, imr, and otr regions of centromere I and an unrelated euchromatic control (fbp) (Figure 2C). In wild-type cells, Fta2 associates with the central centromere region as shown by the specific enrichment of the cnt and imr sequences in the Fta2-GFP ChIP (Figure 2C) (Liu et al., 2005). In mal2-1 cells, Fta2 ChIPs also showed enrichment of the cnt and imr sequences at the permissive temperature (25°C); however, incubation at the nonpermissive temperature led to a severe reduction of the cnt and imr sequences brought down by ChIP (Figure 2C). These data imply that Fta2 localization at the kinetochore was dependent on Mal2.

Figure 2.

Fta2 kinetochore localization is dependent on functional Mal2. (A) Localization of the Fta2-GFP protein in wild-type cells in interphase (a) and early, middle, and late mitosis (b [left cell]–d, respectively). Fixed cells were stained with DAPI and anti-GFP antibody. Bar, 5 μm. (B) Localization of Fta2-GFP in an early mitotic mal2-1 cell. Cells were incubated for 6 h at 36°C, fixed, and stained with DAPI, anti-tubulin antibody, and anti-GFP antibody. Bar, 5 μm. (C) Fta2 association with the central domain of cen1 is Mal2 dependent. Wild-type or mal2-1 cells expressing Fta2-GFP were fixed and processed for ChIP by using anti-GFP antibodies. The chromatin in immunoprecipitates and in the crude extracts was analyzed by multiplex PCR. The amplified regions in cen1 are indicated. fbp, euchromatic negative control. The cnt and imr regions are enriched in Fta2-GFP ChIPs from wild-type cells; the association of Fta2-GFP with these regions is reduced or severely reduced in mal2-1 cells grown at 25 or 36°C (for 6 h), respectively. (D) Fta2 is involved in cnt centromeric silencing. Serial dilution patch tests (104 to 101 cells) of wild-type, fta2-292, and sim4-193 cells that have the arg3+ gene inserted at cnt1. Alleviation of silencing leads to growth on arginine minus (−arg) plates. Cells were incubated at 30°C for 5 d.

Because mutations in genes encoding components of the kinetochore affect centromeric silencing (Pidoux and Allshire, 2000), we tested whether marker genes placed within the centromere DNA were still transcriptionally repressed in the fta2-292 ts mutant strain (see below). To this end, we assayed growth of fta2-292 strains that had the ura4+ marker gene inserted at otr2 (otr region of centromere 2) or imr1, or the arg3+ marker gene inserted at cnt1 (Partridge et al., 2000; Pidoux et al., 2003). Wild-type strains carrying a marker gene inserted at a centromeric region are auxotroph for that particular marker due to transcriptional repression of the centromeric DNA (Pidoux and Allshire, 2000). The presence of fta2-292 had no influence on transcriptional silencing of the otr and imr regions but led to alleviation of silencing at the central cnt region (our unpublished data; Figure 2D). Wild-type strains containing the promoter-crippled arg3+ gene inserted into the cnt1 region grow very poorly on medium that does not contain arginine, whereas kinetochore mutants such as sim4-193 alleviate cnt1 silencing and allow fast growth on arginine minus medium (Figure 2D) (Pidoux et al., 2003). The presence of the mutant fta2-292 allele led to good growth on medium without arginine implying that transcriptional silencing of the cnt1 region has been alleviated (Figure 2D).

fta2 Mutants Show Severe Defects in Chromosome Segregation and Bipolar Attachment

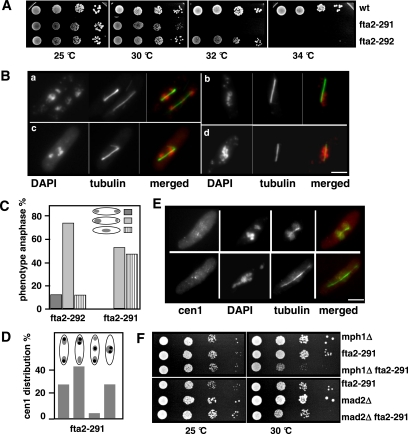

To study the function of Fta2 in mitosis, we generated ts fta2 alleles (see Materials and Methods). The two mutant fta2 strains that showed the tightest ts phenotype were analyzed in greater detail. DNA sequence analysis revealed that both strains carried a single point mutation in the fta2 ORF, one mutation at position 871 (G to A), and the other mutation at position 874 (T to C). The single base-pair changes resulted in single amino acid changes at position 291 (a change from glycine to serine) and position 292 (a change from phenylalanine to leucine) of the 351-amino acid-long Fta2 protein. The mutants were therefore named fta2-291 and fta2-292, respectively (Figure 3A). Because the entire fta2+ ORF was mutagenized but the two mutants with the most prominent ts phenotype had mutations in proximity to each other, we reasoned that the C-terminal region of Fta2 played an important role in its function. We therefore conducted another database search using WU-BLAST2 for putative Fta2 homologues using the last 81 C-terminal amino acids only (Altschul et al., 1997). We found a very limited homology to the S. cerevisiae kinetochore protein Ctf13 (36% identical, 50% similar amino acids in a 63-amino acid-long region) (Supplemental Figure 2) (Doheny et al., 1993). Ctf13 is one of the four proteins of the CBF3 kinetochore complex, which is the essential centromere DNA binding complex in budding yeast (Doheny et al., 1993; Russell et al., 1999).

Figure 3.

ts fta2 mutants have severe mitotic defects. (A) Serial dilution patch tests (104 to 101 cells) of wild-type (wt), fta2-291, and fta2-292 strains grown at the indicated temperatures for 3 d. (B) Photomicrographs of mitotic fta2-291 (a and b) and fta2-292 (c and d) cells incubated for 6 h at 36°C. Fixed cells were stained with DAPI and anti-tubulin antibody. Shown are the main two phenotypes: unequally/partially segregated (a and c) or nonseparated (b and d) chromatin on an elongating spindle. (C) Diagrammatic representation of anaphases observed in fta2-291 and fta2-292 strains incubated for 6 h at 36°C. N/strain = 60. (D) Diagrammatic representation of cen1 distribution in mitotic fta2-291 cells with an elongating spindle (cen1 signal, black dot). (E) Distribution of GFP-marked cen1 in mitotic fta2-291 cells. Cells were incubated for 6 h at 36°C, fixed, and stained with anti-GFP antibody, DAPI, and anti-tubulin antibody. (F) fta2-291 interacts genetically with a component of the spindle checkpoint pathway. Serial dilution patch tests of mph1Δ, mad2Δ, fta2-291 and the respective fta2-291 double mutants grown at the indicated temperatures for 3 d.

Interestingly, in this alignment the amino acids at position 291 and 292 of Fta2 were conserved (Supplemental Figure 2). However, at present it is unclear whether Ctf13 and Fta2 share a common domain.

To analyze the reason for the nongrowth phenotype of the fta2 mutant strains at higher temperatures, fta2-291 and fta2-292 strains were incubated at the nonpermissive temperature for 6 h and analyzed by immunofluorescence. Although interphase cells showed no obvious abnormalities, mitotic cells were severely affected. All fta2-291 mitotic cells and 86% of fta2-292 mitotic cells showed severe chromosome segregation defects (Figure 3, B and C). The two predominant abnormal chromosome resolution phenotypes were 1) unequally or partially separated chromatin (Figure 3B, a and c) and 2) no separation of highly condensed chromatin on an elongating spindle (Figure 3B, b and d). The chromatin was separated, albeit unequally, in the majority of fta2-292 mitotic cells, whereas nearly 50% of fta2-291 mitotic cells were unable to separate their chromatin (Figure 3C). Aberrant spindle phenotypes were observed rarely. To further characterize the severe chromosome segregation defects observed in fta2 mutant cells, we analyzed the segregation behavior of sister centromeres by monitoring the segregation behavior of centromere 1 marked with GFP (cen1-gfp) (Nabeshima et al., 1998). In interphase cells, the distribution of the cen1-GFP signals was very similar to that observed for wild-type cells, indicating that premature sister chromatid separation was not the cause of the aberrant chromatin distribution seen in fta2 mutants. In mitotic cells, only 26.7% of fta2-291 cells with an elongating spindle showed correct separation of cen1 sister centromeres, although the chromatin in these cells was distributed unequally (Figure 3D). In 42.3% of cells, the sister centromeres segregated together, possibly due to syntelic microtubule attachment (Figure 3, D and E). In 3.8% of the cells, only one of the sister centromeres segregated to the end of the cell. Finally, in 26.7% of cells, sister chromatids were not segregated and remained in the middle of the cell (Figure 3D).

We next asked whether all centromeres were associated with the mitotic spindle by assaying colocalization of the cen1-GFP signal and the spindle (Figure 3E). We found that in cells with segregated chromatin 75% of cen1-GFP signals were spindle associated, whereas 25% were not. In cells with an elongating spindle but unseparated chromatin, the majority (58%) of cen1-GFP signals did not colocalize with the mitotic spindle. Our findings imply that the Fta2 protein is required for correct bipolar chromosome orientation and also plays a role in linking the kinetochore to spindle microtubules. The observed fta2 mutant phenotypes should lead to activation of the spindle checkpoint.

This checkpoint regulates entry into anaphase by inhibiting the anaphase promoting complex until proper spindle microtubules association of the kinetochores. The absence of spindle microtubules will activate the attachment response, whereas the tension response will be activated in response to the absence of tension between sister kinetochores (Musacchio and Hardwick, 2002; Cleveland et al., 2003). We tested whether the spindle checkpoint was active in fta2 mutant cells by constructing double mutants of fta2-291 with null alleles of mad2+ and mph1+, which encode conserved components of the spindle checkpoint pathway (He et al., 1997, 1998). The growth properties of mad2Δ (mad2+ deletion) fta2-291 double mutants were indistinguishable from that of the single fta2-291 mutant (Figure 3F). In contrast, mph1Δ fta2-291 strains showed growth defects at 30°C (Figure 3F). We analyzed the phenotypic consequences of an mph1+ deletion in fta2-291 strain by incubation of the single and double mutants for 8 h at 30°C followed by DAPI staining. At this temperature, 47.1% of fta2-291 anaphase cells showed aberrant chromosome segregation, whereas in the mph1Δ fta2-291 double mutant, this number rose to 64.1% (our unpublished data). Our results indicate that the mph1+ spindle checkpoint branch is required for survival of the fta2-291 strain at 30°C.

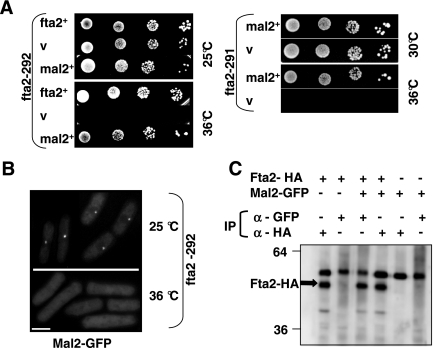

Extra Mal2 Can Suppress the fta2 ts Mutant Phenotypes

Because fta2+ was isolated as a suppressor of the mal2-1 mutant phenotypes, it was of interest to see whether extra mal2+ could suppress the fta2 mutant phenotypes. mal2+ driven by its own promoter on plasmid pUR19 rescued the ts phenotype of the fta2-292 strain at all temperatures tested (Figure 4A, left), whereas it could only rescue the ts phenotype of the fta2-291 strain up to 34°C. However overexpression of mal2+ from the repressible, wild-type nmt1+ promoter resulted in suppression of the fta2-291 nongrowth phenotype at all temperatures tested (Figure 4A, right). Thus, suppression of the fta2 ts phenotype by mal2+ occurs in the same dosage-dependent manner as has been observed for the suppression of mal2-1 by fta2+. It was therefore not surprising that the kinetochore localization of a Mal2-GFP fusion protein was affected in fta2 mutants (Figure 4B). The kinetochore association of Mal2-GFP was not affected in fta2 mutants grown at the permissive temperature, but it was reduced severely in fta2 ts cells incubated at the restrictive temperature (Figure 4B). Mal2-GFP protein levels were not affected in fta2 mutant strains incubated at the restrictive temperature (Supplemental Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Extra mal2+ suppresses the ts nongrowth phenotypes of the fta2 mutant strains. (A) Serial dilution patch tests (104 to 101 cells) of fta2-292 and fta2-291 transformants grown under selective conditions at the indicated temperatures for 4 d. Vector control (v) indicates plasmid without insert; Mal2+ denotes the presence of wild-type mal2+ expressed by the endogenous promoters on plasmid pUR19 (for fta2-292) or from the thiamine-repressible nmt1+ promoter in the absence of thiamine (for fta2-291). (B) Kinetochore localization of Mal2-GFP is abolished in the fta2-292 strain at the nonpermissive temperature. fta2-292 cells expressing Mal2-GFP were grown at 25°C or shifted for 6 h to 36°C and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. (C) Coimmunoprecipitation of Fta2 and Mal2. Protein extracts from strains expressing Mal2-GFP, Fta2-HA, or both were used for immunoprecipitation (IP) with an anti-HA or anti-GFP antibody. The immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed with an anti-HA antibody. Kilodalton size markers are indicated.

Given the close genetic interaction between mal2+ and fta2+, we investigated whether the Mal2 and Fta2 proteins interacted. For this purpose, we tested whether HA-tagged Fta2 could be coimmunoprecipitated by GFP-tagged Mal2. Immunoprecipitation with anti-HA or anti-GFP antibodies was carried out with protein extracts from strains that expressed endogenous Fta2-HA and/or Mal2-GFP. We found that Mal2-GFP strongly coimmunoprecipitated Fta2-GFP. Fta2-HA could also coimmunoprecipitate Mal2-GFP (Supplemental Figure 3).

Given the close physical and genetic interaction between fta2+ and mal2+, we were interested to analyze the phenotype of fta2 mal2 double mutants. However, we were unable to construct mal2-1 fta2-291 or mal2-1 fta2-292 mutants by tetrad analysis at 25°C. The mal2-1 fta2 double mutant spores germinated, and cells divided two to three times before dying (see Materials and Methods).

Interaction between Fta2 and Other Components of the Sim4 Kinetochore Subcomplex

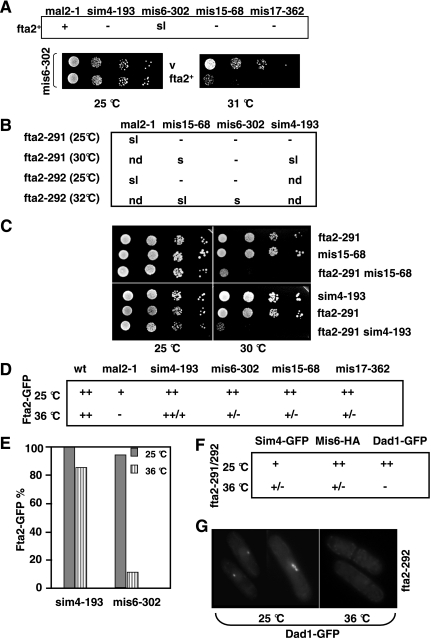

Recently, Fta2 and Mal2 were identified as components of the Sim4 kinetochore complex (Liu et al., 2005). The Sim4 complex consists of the previously identified proteins Sim4, Mal2, Mis6, Mis15, and Mis17; the DASH component Dad1; and seven novel proteins, Fta1-7 (Goshima et al., 1999; Jin et al., 2002; Pidoux et al., 2003; Hayashi et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2005). Given the close interaction between Mal2 and Fta2 for all parameters tested, we assayed the interaction between Fta2 and other components of the Sim4 complex. We first tested suppression of all existing conditional lethal alleles of the Sim4 complex components by overexpression of fta2+. fta2+ expressed from the repressible, wild-type nmt1+ promoter was unable to suppress the nongrowth phenotype of the ts sim4-193, mis6-302, mis15-68, or mis17-362 strains even at semipermissive temperatures (Figure 5A). In fact, overexpression of fta2+ in mis6-302 was synthetic lethal at 31°C, a temperature that has only a slight effect on the growth of the mis6 mutant transformed with a vector control (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Interaction between fta2+ and other components of the Sim4 kinetochore complex. (A) Plasmid-borne expression of fta2+ from the nmt1+ promoter rescues the ts phenotype of a mal2-1 mutant (+), leads to synthetic lethality (sl) of a mis6-302 mutant at the semipermissive temperature and has no effect (−) on the growth of the sim4-193, mis15-68, and mis17-362 strains at temperatures below the restrictive temperature. Serial dilution patch tests of mis6-302 transformants grown under selective conditions at the indicated temperatures for 4 d. v, vector control. (B) Growth of double mutants of fta2-291 and/or fta2-292 with other components of the Sim4 complex. sl, synthetic lethal; s, reduced growth; −, no effect; nd, not done. (C) Serial dilution patch tests of fta2-291, mis15-68, sim4-193, and double mutants grown on YE5S for 4 d (25°C) or 3 d (30°C). (D) Kinetochore localization of a Fta2-GFP fusion protein in the indicated ts strains. All strains were incubated for 6 h at the nonpermissive temperature before fixation. Wt, wild-type; ++, wild-type–like localization to −, no localization. N/strain = 140. (E) Diagrammatic representation of Fta2-GFP kinetochore localization in sim4-193 and mis6-302 cell populations. N/strain = 140. (F) Kinetochore localization of Sim4-GFP, Mis6-HA in a fta2-291 mutant and Dad1-GFP in a fta2-292 mutant grown for 6 h at the restrictive temperature. ++, wild-type–like localization to −, no localization. N/strain = 140. (G) Dad1-GFP localization was analyzed in living fta2-292 cells grown at 25 or 36°C for 6 h.

Next, double mutants of fta2-291 and/or fta2-292 with sim4-193, mis6-302, mis15-68 were constructed by tetrad analysis. In contrast to the fta2 mal2-1 double mutants, which were inviable, all of these double mutants were able to grow normally at 25°C. However, at higher temperatures, synthetic effects were observed that resulted in poor growth at that particular temperature (Figure 5B). As an example, single and double mutant strains of fta2-291 and mis15-68 and sim4-193 are shown (Figure 5C). To determine whether kinetochore localization of Fta2 was affected in mutants of the Sim4 complex, we assayed localization of a Fta2-GFP fusion protein in sim4-193, mis6-302, mis15-68, and mis17-262 mutants. At the permissive temperature (25°C), no difference in Fta2-GFP staining was observed between a wild-type strain and the Sim4 complex mutants, with the exception of the mal2-1 mutant, which showed less intense Fta2-GFP signals (Figure 5D; our unpublished data). At the nonpermissive temperature, no Fta2-GFP signal was observed in mal2-1 cells (Figure 2B), and severely reduced signals were observed in mis6-302, mis15-68, and mis17-362 cells (Figure 5D). For example, only 10% of mis6-302 cells incubated for 6 h at 36°C showed a wild-type–like Fta2-GFP signal; all other cells had a severely reduced or no GFP signal (Figure 5E). This phenotype was irrespective of the cell cycle phase, although interphase cells showed a higher percentage of cells with no GFP signal/versus reduced signal than mitotic cells. Analysis of a Mis6-HA fusion protein in the fta2-291 mutant gave a similar result (Figure 5F).

Surprisingly, the presence of the mutant sim4 allele had only mild effects on the correct localization of Fta2-GFP. After 6–8 h at the restrictive temperature, 86% of sim4-193 cells showed wild-type–like Fta2-GFP signals (Figure 5E). However, the correct localization of a Sim4-GFP fusion protein was dependent on Fta2, because kinetochore localization of Sim4-GFP in the fta2-291 mutant was reduced severely (Figure 5F; our unpublished data).

These results imply that the Sim4 kinetochore complex is build up hierarchically. Mal2 is absolutely required for kinetochore localization of Fta2. Mis6, Mis15, and Mis17 are also needed for Fta2 localization, but to a somewhat lesser degree, whereas Sim4 does not seem to be required. Fta2 is absolutely required for kinetochore localization of Mal2 and plays an important role in the correct localization of Mis6 and Sim4 proteins.

Finally, it has been shown previously that Sim4 complex components are required for association of the DASH complex (Sanchez-Perez et al., 2005). We therefore tested whether Dad1, a constitutive component of the DASH complex was localized correctly in fta2-292 mutant cells and found that kinetochore localization of Dad1-GFP was dependent on functional fta2+ (Figure 5, F and G).

Wild-Type–like Fta2 Localization Requires Spc7, a Component of the Ndc80–MIND–Spc7 Kinetochore Complex

Recently, the Ndc80–MIND–Spc7 kinetochore complex has been described (Obuse et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2005). This complex seems to exist independently of the Sim4 complex (Liu et al., 2005).

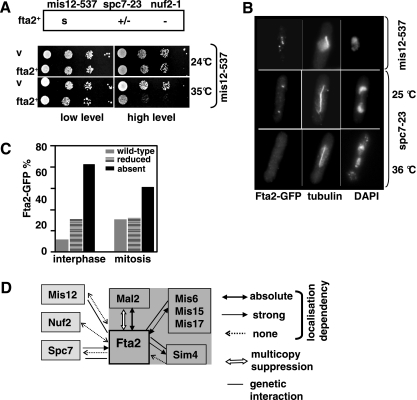

To analyze a possible interaction between Fta2 and components of the Ndc80–MIND–Spc7 complex, we overexpressed fta2+ in mis12-537, nuf2-1, and spc7-23 mutant strains at various temperatures up to the maximally permissive temperatures. The Mis12 protein is part of the MIND complex, whereas Nuf2 is a component of the Ndc80 complex. Extra fta2+ had no effect on the growth of a nuf2–1 mutant, a slight negative effect on the spc7-23 mutant and gave rise to reduced growth of the mis12-537 mutant strain (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Interaction of fta2+ with components of the Ndc80–MIND–Spc7–kinetochore complex. (A) Growth phenotype of mis12-537, spc7-23, and nuf2–1 strains transformed with pREPfta2+. s, reduced growth; +/−, slightly reduced growth; −, no effect. The serial dilution patch tests (104 to 101 cells) show a mis12-537 strain transformed with pREPfta2+ grown under selective conditions and under nmt1+ promoter repressing (low) or derepressing (high) conditions for 6 d. (B) Photomicrographs of mis12-537 and spc7-23 cells expressing Fta2-GFP. The spc7-23 strain was incubated at 25°C or for 6 h at 36°C, the mis12-537 strain for 6 h at 36°C, fixed, and stained with DAPI, anti-tubulin antibody, and anti-GFP antibody. Bar, 5 μm. (C) Diagrammatic representation of Fta2-GFP in a spc7-23 cell population incubated for 6 h at 36°C. N/cell cycle phase, 55. (D) Summary of the interactions between Fta2 and components of the Sim4 and Ndc80–MIND–Spc7 complexes.

To test whether Fta2 kinetochore localization was dependent on the Ndc80–MIND–Spc7 complex, subcellular localization of the Fta2-GFP fusion protein was determined in mis12-537, nuf2-1, and spc7-23 ts strains (Goshima et al., 1999; Nabetani et al., 2001; Kerres et al., 2004). Kinetochore localization of Fta2-GFP was unaffected in mis12-537 and nuf2-1 mutant strains incubated at the nonpermissive temperature (Figure 6B; our unpublished data). However, surprisingly, Fta2-GFP localization was affected in the spc7-23 strain at the restrictive temperature (Figure 6B). spc7-23 encodes a ts mutant Spc7 protein that has a severely reduced kinetochore association at the restrictive temperature, leading to spindle defects and massive chromosome missegregation (Kerres, Jakopec, and Fleig, unpublished data). Whereas Fta2-GFP kinetochore localization was unaffected in a spc7-23 strain grown at 25°C (Figure 6B), the signal intensity of the fusion protein was reduced or absent in the majority of spc7-23 cells incubated at the restrictive temperature (Figure 6, B and C). Fta2 proteins levels were similar in spc7-23 and wild-type cells (Supplemental Figure 1). Thus, Spc7 is required for correct localization of the Sim4 complex component Fta2. However, a Spc7-GFP fusion protein is localized correctly in a fta2 mutant (our unpublished data).

DISCUSSION

We investigated the role of the conserved Mal2 protein in mitosis by screening for extragenic suppressors that were able to rescue the mal2-1 ts phenotype at a semipermissive growth temperature and thus identified the essential kinetochore component Fta2. Both proteins were recently shown to be members of the Sim4 kinetochore complex (Liu et al., 2005).

Our characterization of Fta2 shows that it localizes to the central domain of the fission yeast centromere, where it is required for transcriptional silencing. This specific alleviation of central core silencing has also been documented for other mutant components of the Sim4-complex, such as Mis6, Mal2, and Sim4, and probably reflects defects in the assembly of the kinetochore (Allshire et al., 1995; Jin et al., 2002; Pidoux et al., 2003). The ts fta2 mutants show a very high number of aberrant mitosis with no or unequal separation of the condensed chromatin indicating the important role of Fta2 in kinetochore function. The high frequency of mitotic cells with nonseparated chromatin on an elongating spindle (nearly 50% in the fta2-291 strain) has so far not been observed for other mutant components of the Sim4 complex and implies that kinetochore function is severely affected in fta2 mutants.

Analysis of the segregation behavior of tagged cen1 sister centromeres indicated that Fta2 is required for bipolar chromosome orientation. In addition, 44% of cen1-GFP signals did not seem to be spindle associated in anaphase fta2 mutants, implying that Fta2 also plays a role in linking the kinetochore to microtubule plus-ends.

The spindle checkpoint monitors spindle–kinetochore interaction and becomes activated when the mitotic chromosomes are not under tension or/and are not microtubule associated (Musacchio and Hardwick, 2002; Cleveland et al., 2003). Given the phenotype of the fta2 mutants, one would expect activation of the spindle checkpoint in these strains. Indeed, we observed that in the absence of the spindle checkpoint component Mph1, the temperature sensitivity and chromosome missegregation phenotype of a fta2 mutant strain was increased significantly. However, double mutants between fta2-291 and mad2Δ behaved like the fta2-291 single mutant. Recently, it has been shown that Mis6 is required for the association of Mad2 with the kinetochore during mitosis (Saitoh et al., 2005). Because the Mis6 protein is not localized correctly in fta2 mutants, we presume that the Mad2-dependent part of the spindle checkpoint pathway is impaired in fta2 mutants and thus unable to sense the aberrant microtubule–kinetochore interactions.

Fta2 is a component of the 13-component Sim4 kinetochore complex that comprises the previously identified proteins Mal2, Mis6, Sim4, Mis15, and Mis17; the DASH component Dad1; and the seven new Fta1-7 proteins (Liu et al., 2005). Apart from the nonessential Dad1 protein, all other Sim4 complex components analyzed to date are essential for precise chromosome transmission. However, the phenotypes caused by various mutant alleles coding for Sim4 complex components are not identical (Fleig et al., 1996; Goshima et al., 1999; Jin et al., 2002; Pidoux et al., 2003; Hayashi et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2005; Sanchez-Perez et al., 2005). For example, mal2-1 and sim4-193 mutants are hypersensitive to microtubule-destabilizing drugs, whereas others, such as mis6-302 or fta2 mutants, are not (Jin et al., 2002; Pidoux et al., 2003; our unpublished data). By analyzing the interactions between Fta2 and other members of the Sim4 complex, we have started to identify functional subgroups within this complex (Figure 6F). In particular, the tight functional interaction with Mal2 was not observed for other members of this complex. mal2+ overexpression strongly suppressed the ts phenotype of the fta2 mutants in a dosage-dependent manner. The same held true for the rescue of the mal2-1 ts phenotype by extra fta2+. Furthermore, kinetochore localization of these proteins was absolutely dependent on each other. These data imply that Mal2 and Fta2 work together in a subgroup of the Sim4 complex. Because fta2 mal2-1 double mutants could not be obtained at any temperature, fta2 and mal2 mutants require the presence of the other wild-type partner protein for survival at the permissive temperature.

Such a close functional interaction has not been observed for any other members of the Sim4 complex. For example, all double mutants of essential Sim4 complex components generated to date were viable at the permissive temperature (22–26°C) and showed growth impairment only at higher temperatures (Pidoux et al., 2003; Hayashi et al., 2004) (Figure 5B).

Furthermore, reciprocal suppression has not yet been observed for any other members of the Sim4 complex. Although Mis6, Mis17, and Mis15 proteins show strong coimmunoprecipitation and depend on each other for correct kinetochore localization, they show no suppression of each others mutant phenotype (Hayashi et al., 2004). Extra Sim4 protein is able to rescue the ts phenotype of a mis6-302 mutant; however, the converse is not true (Pidoux et al., 2003). We have shown that fta2+ or mal2+ overexpression did not rescue the ts phenotype of sim4-193, mis15-68, and mis17-362 mutant strains and that extra fta2+ in the mis6-302 mutant gave rise to a synthetic lethal phenotype. Interestingly, gfp-tagged fta2+ in mis17-365 and mis15-68 but not other Sim4 component strains resulted in an increased ts sensitivity of these strains (our unpublished data), possibly implying that Fta2 and Mis17/Mis15 are in proximity to each other.

Kinetochore localization of Fta2 was absolutely dependent on Mal2; strongly dependent on functional Mis15, Mis17, and Mis6 proteins; but unaffected in sim4 mutant cells, implying that the Sim4 complex is build up in a hierarchical manner (Figure 6F).

Interestingly, we found that wild-type–like kinetochore localization of Fta2 is dependent on the presence of a functional Spc7 protein. Spc7, which was isolated as a suppressor of the EB1 family member Mal3 and plays a role at the microtubule–kinetochore interface, is closely associated with the Ndc80 and MIND complexes (Kerres et al., 2004; Obuse et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2005). Our data thus indicate an interaction between the Ndc80–MIND–Spc7 and Sim4 complexes, which is possibly mediated via Spc7 and Fta2. The functional significance of this interaction awaits further analysis; however, given the finding that Spc7 associates with the microtubule plus-end–associating protein Mal3 and that the Sim4 complex Fta2 is required for kinetochore association of the DASH complex, it is possible that this interaction contributes to the dynamic microtubule–kinetochore interface.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Yanagida, Y. Hiraoka, J. Millar, S. Sazer, and K. Gould for strains; E. Walla for excellent technical assistance; J. Hegemann for support; and K. Gull for the anti-tubulin antibody TAT1. The initial stages of this work were supported by funds from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to U.F.)

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E06-04-0264) on July 19, 2006.

REFERENCES

- Allshire R. C., Javerzat J. P., Redhead N. J., Cranston G. Position effect variegation at fission yeast centromeres. Cell. 1994;76:157–169. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allshire R. C., Nimmo E. R., Ekwall K., Javerzat J. P., Cranston G. Mutations derepressing silent centromeric domains in fission yeast disrupt chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:218–233. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schaffer A. A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D. J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahler J., Wu J. Q., Longtine M. S., Shah N. G., McKenzie A., 3rd, Steever A. B., Wach A., Philippsen P., Pringle J. R. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast. 1998;14:943–951. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<943::AID-YEA292>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbet N., Muriel W. J., Carr A. M. Versatile shuttle vectors and genomic libraries for use with Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Gene. 1992;114:59–66. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90707-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge A. J., Morphew M., Bartlett R., Hagan I. M. The fission yeast SPB component Cut12 links bipolar spindle formation to mitotic control. Genes Dev. 1998;12:927–942. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.7.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland D. W., Mao Y., Sullivan K. F. Centromeres and kinetochores: from epigenetics to mitotic checkpoint signaling. Cell. 2003;112:407–421. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wulf P., McAinsh A. D., Sorger P. K. Hierarchical assembly of the budding yeast kinetochore from multiple subcomplexes. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2902–2921. doi: 10.1101/gad.1144403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai A., Rybina S., Muller-Reichert T., Shevchenko A., Hyman A., Oegema K. KNL-1 directs assembly of the microtubule-binding interface of the kinetochore in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2421–2435. doi: 10.1101/gad.1126303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doheny K. F., Sorger P. K., Hyman A. A., Tugendreich S., Spencer F., Hieter P. Identification of essential components of the S. cerevisiae kinetochore. Cell. 1993;73:761–774. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90255-O. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleig U., Sen-Gupta M., Hegemann J. H. Fission yeast mal2+ is required for chromosome segregation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:6169–6177. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltz D. R., Jansen L. E., Black B. E., Bailey A. O., Yates J. R., 3rd, Cleveland D. W. The human CENP-A centromeric nucleosome-associated complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:458–469. doi: 10.1038/ncb1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukagawa T. Centromere DNA, proteins and kinetochore assembly in vertebrate cells. Chromosome Res. 2004;12:557–567. doi: 10.1023/B:CHRO.0000036590.96208.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshima G., Saitoh S., Yanagida M. Proper metaphase spindle length is determined by centromere proteins Mis12 and Mis6 required for faithful chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1664–1677. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.13.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan I. M., Hyams J. S. The use of cell division cycle mutants to investigate the control of microtubule distribution in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Cell Sci. 1988;89:343–357. doi: 10.1242/jcs.89.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T., Fujita Y., Iwasaki O., Adachi Y., Takahashi K., Yanagida M. Mis16 and Mis18 are required for CENP-A loading and histone deacetylation at centromeres. Cell. 2004;118:715–729. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Jones M. H., Winey M., Sazer S. Mph1, a member of the Mps1-like family of dual specificity protein kinases, is required for the spindle checkpoint in S. pombe. J. Cell Sci. 1998;111:1635–1647. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.12.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Patterson T. E., Sazer S. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe spindle checkpoint protein mad2p blocks anaphase and genetically interacts with the anaphase-promoting complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:7965–7970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Rines D. R., Espelin C. W., Sorger P. K. Molecular analysis of kinetochore-microtubule attachment in budding yeast. Cell. 2001;106:195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00438-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janke C., Ortiz J., Lechner J., Shevchenko A., Magiera M. M., Schramm C., Schiebel E. The budding yeast proteins Spc24p and Spc25p interact with Ndc80p and Nuf2p at the kinetochore and are important for kinetochore clustering and checkpoint control. EMBO J. 2001;20:777–791. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.4.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Q. W., Pidoux A. L., Decker C., Allshire R. C., Fleig U. The mal2p protein is an essential component of the fission yeast centromere. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:7168–7183. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.20.7168-7183.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerres A., Vietmeier-Decker C., Ortiz J., Karig I., Beuter C., Hegemann J., Lechner J., Fleig U. The fission yeast kinetochore component Spc7 associates with the EB1 family member Mal3 and is required for kinetochore-spindle association. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:5255–5267. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-06-0443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., McLeod I., Anderson S., Yates J. R., 3rd, He X. Molecular analysis of kinetochore architecture in fission yeast. EMBO J. 2005;24:2919–2930. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiato H., DeLuca J., Salmon E. D., Earnshaw W. C. The dynamic kinetochore-microtubule interface. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:5461–5477. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAinsh A. D., Tytell J. D., Sorger P. K. Structure, function, and regulation of budding yeast kinetochores. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2003;19:519–539. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.155607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meraldi P., McAinsh A. D., Rheinbay E., Sorger P. K. Phylogenetic and structural analysis of centromeric DNA and kinetochore proteins. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R23. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-3-r23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno S., Klar A., Nurse P. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:795–823. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94059-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio A., Hardwick K. G. The spindle checkpoint: structural insights into dynamic signalling. Nat Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:731–741. doi: 10.1038/nrm929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabeshima K., Nakagawa T., Straight A. F., Murray A., Chikashige Y., Yamashita Y. M., Hiraoka Y., Yanagida M. Dynamics of centromeres during metaphase-anaphase transition in fission yeast: Dis1 is implicated in force balance in metaphase bipolar spindle. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1998;9:3211–3225. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.11.3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabetani A., Koujin T., Tsutsumi C., Haraguchi T., Hiraoka Y. A conserved protein, Nuf2, is implicated in connecting the centromere to the spindle during chromosome segregation: a link between the kinetochore function and the spindle checkpoint. Chromosoma. 2001;110:322–334. doi: 10.1007/s004120100153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obuse C., Iwasaki O., Kiyomitsu T., Goshima G., Toyoda Y., Yanagida M. A conserved Mis12 centromere complex is linked to heterochromatic HP1 and outer kinetochore protein Zwint-1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:1135–1141. doi: 10.1038/ncb1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M., Cheeseman I. M., Hori T., Okawa K., McLeod I. X., Yates J. R., Desai A., Fukagawa T. The CENP-H-I complex is required for the efficient incorporation of newly synthesized CENP-A into centromeres. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;5:446–457. doi: 10.1038/ncb1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz J., Stemmann O., Rank S., Lechner J. A putative protein complex consisting of Ctf19, Mcm21, and Okp1 represents a missing link in the budding yeast kinetochore. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1140–1155. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.9.1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge J. F., Borgstrom B., Allshire R. C. Distinct protein interaction domains and protein spreading in a complex centromere. Genes Dev. 2000;14:783–791. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidoux A. L., Allshire R. C. Centromeres: getting a grip of chromosomes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2000;12:308–319. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidoux A. L., Allshire R. C. Kinetochore and heterochromatin domains of the fission yeast centromere. Chromosome Res. 2004;12:521–534. doi: 10.1023/B:CHRO.0000036586.81775.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidoux A. L., Richardson W., Allshire R. C. Sim 4, a novel fission yeast kinetochore protein required for centromeric silencing and chromosome segregation. J. Cell Biol. 2003;161:295–307. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polizzi C., Clarke L. The chromatin structure of centromeres from fission yeast: differentiation of the central core that correlates with function. J. Cell Biol. 1991;112:191–201. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.2.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell I. D., Grancell A. S., Sorger P. K. The unstable F-box protein p58-Ctf13 forms the structural core of the CBF3 kinetochore complex. J. Cell Biol. 1999;145:933–950. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.5.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh S., Ishii K., Kobayashi Y., Takahashi K. Spindle checkpoint signaling requires the mis6 kinetochore subcomplex, which interacts with mad2 and mitotic spindles. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:3666–3677. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh S., Takahashi K., Yanagida M. Mis6, a fission yeast inner centromere protein, acts during G1/S and forms specialized chromatin required for equal segregation. Cell. 1997;90:131–143. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80320-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Perez I., Renwick S. J., Crawley K., Karig I., Buck V., Meadows J. C., Franco-Sanchez A., Fleig U., Toda T., Millar J. B. The DASH complex and Klp5/Klp6 kinesin coordinate bipolar chromosome attachment in fission yeast. EMBO J. 2005;24:2931–2943. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K., Chen E. S., Yanagida M. Requirement of Mis6 centromere connector for localizing a CENP-A-like protein in fission yeast. Science. 2000;288:2215–2219. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5474.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K., Murakami S., Chikashige Y., Funabiki H., Niwa O., Yanagida M. A low copy number central sequence with strict symmetry and unusual chromatin structure in fission yeast centromere. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1992;3:819–835. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.7.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann S., Cheeseman I. M., Anderson S., Yates J. R., 3rd, Drubin D. G., Barnes G. Architecture of the budding yeast kinetochore reveals a conserved molecular core. J. Cell Biol. 2003;163:215–222. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigge P. A., Kilmartin J. V. The Ndc80p complex from Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains conserved centromere component and has a function in chromosome segregation. J. Cell Biol. 2001;152:349–360. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.2.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winey M., Mamay C. L., O’Toole E. T., Mastronarde D. N., Giddings T. H., Jr., McDonald K. L., McIntosh J. R. Three-dimensional ultrastructural analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitotic spindle. J. Cell Biol. 1995;129:1601–1615. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.6.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.