Abstract

Spindle positioning is essential for the segregation of cell fate determinants during asymmetric division, as well as for proper cellular arrangements during development. In Caenorhabditis elegans embryos, spindle positioning depends on interactions between the astral microtubules and the cell cortex. Here we show that let-711 is required for spindle positioning in the early embryo. Strong loss of let-711 function leads to sterility, whereas partial loss of function results in embryos with defects in the centration and rotation movements that position the first mitotic spindle. let-711 mutant embryos have longer microtubules that are more cold-stable than in wild type, a phenotype opposite to the short microtubule phenotype caused by mutations in the C. elegans XMAP215 homolog ZYG-9. Simultaneous reduction of both ZYG-9 and LET-711 can rescue the centration and rotation defects of both single mutants. let-711 mutant embryos also have larger than wild-type centrosomes at which higher levels of ZYG-9 accumulate compared with wild type. Molecular identification of LET-711 shows it to be an ortholog of NOT1, the core component of the CCR4/NOT complex, which plays roles in the negative regulation of gene expression at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels in yeast, flies, and mammals. We therefore propose that LET-711 inhibits the expression of ZYG-9 and potentially other centrosome-associated proteins, in order to maintain normal centrosome size and microtubule dynamics during early embryonic divisions.

INTRODUCTION

Asymmetric divisions are a primary mechanism by which cells with differing developmental fates are generated (Betschinger and Knoblich, 2004; Cowan and Hyman, 2004). In order for an intrinsically asymmetric division to occur, cell fate determinants must become asymmetrically localized and the spindle must align along the axis of polarity, so that the determinants are partitioned unequally between the daughter cells during division. Although the molecular mechanisms that position the spindle in response to polarity cues remain to be fully elucidated, studies in several organisms indicate that interactions between astral microtubules and cues at the cell cortex play a major role in this process (Cowan and Hyman, 2004; Pearson and Bloom, 2004; Huisman and Segal, 2005).

The Caenorhabditis elegans embryo has emerged as an excellent system for the study of spindle positioning in multicellular organisms, because wild-type embryos undergo a series of invariant cell divisions in which spindles are positioned on specific axes in both asymmetrically and symmetrically dividing cells (reviewed in Schneider and Bowerman, 2003; Betschinger and Knoblich, 2004; Cowan and Hyman, 2004). After fertilization, the egg pronucleus migrates to meet the sperm pronucleus and its associated centrosomes in the posterior of the embryo. The pronuclear–centrosome complex then moves to the center in a process called centration and rotates onto the polarized axis, and the mitotic spindle forms. During metaphase and anaphase, the spindle moves toward the posterior pole and also elongates asymmetrically toward the posterior, which results in unequal division. Similar nuclear and spindle movements are repeated in asymmetrically dividing daughters of the P lineage, whereas no rotation occurs in cells of the AB lineage. The nuclear and spindle movements are dependent on the PAR polarity proteins, which establish cellular and embryonic polarity, as well as heterotrimeric G protein signaling. The use of PARs and G proteins for spindle positioning is conserved in Drosophila (Schneider and Bowerman, 2003; Betschinger and Knoblich, 2004; Cowan and Hyman, 2004; Bellaiche and Gotta, 2005).

Although it remains to be determined exactly how the PARs and G protein signaling regulate downstream components that position nuclei and spindles, it is clear that interactions between astral microtubules and the cortex are essential in C. elegans. Mutations or treatments that render microtubules too short to contact the cortex cause defects in both rotation and posterior spindle displacement in 1- and 2-cell embryos (Kemphues et al., 1986; Hyman and White, 1987; Matthews et al., 1998; Gonczy et al., 2001; Bellanger and Gonczy, 2003; Le Bot et al., 2003; Srayko et al., 2003). Spindle severing experiments more directly demonstrated that the forces that asymmetrically elongate the spindle during anaphase come from the cortex rather than the central spindle and that these cortical forces are regulated by the PAR polarity proteins (Grill et al., 2001). Similar types of experiments carried out during nuclear rotation and metaphase suggest that cortical forces play a critical role in nuclear rotation and metaphase spindle displacement as well (Labbe et al., 2004). The microtubule motor dynein and its associated dynactin complex are required for centration and rotation (Skop and White, 1998; Gonczy et al., 1999; Schmidt et al., 2005), suggesting that dynein anchored at the cortex is one source of the force that moves the spindle.

Microtubule–cortex interactions important for spindle positioning are influenced by microtubule dynamics. A small number of proteins that influence centrosome/spindle positioning and regulate microtubule dynamics have been described in C. elegans. ZYG-9, a C. elegans XMAP215 homolog, is required for spindle positioning during the first division. Reduction of ZYG-9 function results in short microtubules, leading to defects in female pronuclear migration, nuclear-centrosome centration and rotation, and spindle elongation (Kemphues et al., 1986; Matthews et al., 1998). Recent work has shown that ZYG-9 promotes microtubule polymerization (Srayko et al., 2005), a role consistent with studies of several other XMAP215 family members (Tournebize et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2001; Graf et al., 2003; Holmfeldt et al., 2004; Brittle and Ohkura, 2005). The same phenotype as that observed for zyg-9 embryos is seen in embryos depleted of TAC-1, a coiled-coil protein that binds to ZYG-9 and is required for ZYG-9 localization and stability (Bellanger and Gonczy, 2003; Le Bot et al., 2003; Srayko et al., 2003). Reduction of ZYG-8, a microtubule-associated protein that can protect microtubules against depolymerization by cold or drug treatment, also causes nuclear and spindle positioning defects in 1-cell embryos (Gonczy et al., 2001). Interestingly, examination of microtubules in zyg-8 embryos revealed shorter microtubule lengths during anaphase but not rotation, suggesting that small changes in microtubule length and/or dynamics can have a major affect on spindle positioning.

Whether proteins required for microtubule dynamics, such as ZYG-9/TAC-1 and ZYG-8, are regulated in an asymmetric manner by the PAR polarity pathway remain to be determined. Nonetheless, it is likely that the overall activity of microtubule binding proteins must be tightly regulated for normal spindle positioning to occur, because too much activity would be predicted to result in longer than normal microtubules with altered dynamics. Such regulation could be accomplished through the opposing activities of microtubule depolymerizing factors (Tournebize et al., 2000; Kinoshita et al., 2001; Holmfeldt et al., 2004; Wordeman, 2005). The only depolymerization factor that has been examined in detail in C. elegans is CeMCAK (aka klp-7), the homolog of the MCAK and XKCM1 kinesin family proteins (Grill et al., 2001; Oegema et al., 2001; Srayko et al., 2005). Based on in vitro studies showing that MCAK can balance the activity of XMAP215 (Tournebize et al., 2000), depletion of CeMCAK in C. elegans embryos may have been predicted to produce long microtubules and defects in spindle positioning. However, although RNA interference studies (RNAi) have revealed strong defects in meiosis and kinetochore microtubule function at mitosis, no obvious defects in centration or nuclear rotation have been observed (Oegema et al., 2001; DeBella and Rose, unpublished results). Further, from analysis of microtubule polymerization rates in living C. elegans embryos, it has been suggested that CeMCAK plays a role in nucleation, but not polymerization rate, and thus that CeMCAK and ZYG-9 act in different pathways in this system (Srayko et al., 2005). In addition, RNAi of several other microtubule-associated proteins did not reveal any proteins with opposite effects on polymerization compared with zyg-9(RNAi), and ZYG-9/TAC-1 appeared to be the major contributor to polymerization (Srayko et al., 2005).

An alternative means of regulating ZYG-9/TAC-1 and ZYG-8 activity, and thus microtubule length, would be to control their localization or amounts in a cell cycle–dependent manner or during the course of development. For example, it is known that ZYG-9 localization at the centrosome is regulated as part of centrosome maturation, the process by which additional centrosomal antigens accumulate and more microtubules are nucleated as mitosis proceeds. A block in centrosome maturation results in a decrease in the level of ZYG-9 and other centrosome-associated proteins and thus small asters (Hannak et al., 2001, 2002). However, it is not clear how centrosome-associated proteins are regulated during the cell cycle to prevent excess accumulation.

In this article we describe a new gene, let-711, which was identified based on defects in positioning of the mitotic spindle. The spindle positioning phenotypes correlate with the presence of longer microtubules that are more cold-stable than in wild type, a phenotype opposite to that of zyg-9 mutants. Simultaneous reduction of both ZYG-9 and LET-711 leads to more wild-type spindle positioning than in either single mutant. Interestingly, let-711 mutant embryos have larger than wild-type centrosomes at which more ZYG-9 accumulates, suggesting that LET-711 acts through ZYG-9 and other proteins, rather than directly on microtubules. Consistent with this model, LET-711 is an ortholog of the NOT1 gene, which regulates several distinct levels of gene expression in other systems. These results show that let-711 is required for the regulation of microtubule length through effects on the expression of centrosome-associated proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and Genetics

C. elegans were cultured on MYOB plates (Church et al., 1995) using standard conditions (Brenner, 1974). The following strains were kindly provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, Drs. D. Bailey (BC strains), B. Bowerman (EU), K. Oegema/A. Desai (OD), K. Kemphues (KK) or were constructed in the Rose laboratory (RL). N2 or unc-32 worms were used for all wild-type (let-711+) controls: N2: wild-type, Bristol variant; CB4856: wild type, Hawaiian variant; KK72: unc-32(e189) III; KK93: him-3(e1147) egl-23(n601) IV; RL67: lon-1(e185) let-711(it150ts) unc-32(e189)/qC1 III; RL93: dpy-17(e164) let-711(s2587) unc-32(e189)/qC1 III; RL116: sma-3(e491) let-711(s2587) unc-32(e189)/sma-3(e491) unc-36(e251) III; BC4183: dpy-17(e164) let-711(s2473) unc-32(e189)III;sDp3(III;f); BC4184: dpy-17(e164) let-711(s2474) unc-32(e189)III;sDp3(III;f); BC4227: dpy-17(e164) let-711(s2587) unc-32(e189)III;sDp3(III;f); BC4989: dpy-17(e164) let-711(s2790) unc-32(e189)III;sDp3(III;f); BC4152: dpy-17(e164) let-771(s2442) unc-32(e189) III;sDp3(III;f); BC4241: dpy-17(e164) let-783(s2601) unc-32(e189)III;sDp3(III;f); BC4267: dpy-17(e164) let-843(s2627) unc-32(e189)III;sDp3(III;f); BC4634: dpy-17(e164) sDf125(s2424) unc-32(e189)III; sDp3(III,f); BC4638: dpy-17(e164) sDf127(s2428) unc-32(e189)III; sDp3(III,f); BC4677: dpy-17(e164) sDf135(s2767) unc-32(e189)III; sDp3(III,f); BC4828: dpy-17(e164) let-792(s2798) nd-1(e1865) unc-32(e189)III;sDp3(III;f); BC4855: dpy-17(e164) let-793(s2825) nd-1(e1865) unc-32(e189)III;sDp3(III;f); BC4879: dpy-17(e164) let-795(s2849) nd-1(e1865) unc-32(e189)III;sDp3(III;f); BC4863: dpy-17(e164) cyk-1(s2833) nd-1(e1865) unc-32(e189)III;sDp3(III;f); EU709: unc-50(e306) rfl-1(or198ts) III; and OD44: unc-119 (ed3) III; ltIs2 [pIC27-4: pie-1::GFP-TEV-Stag::tbg01cDNA; unc-119(+)].

The it150 mutation was identified in screens for maternal effect lethal mutations that cause defects in spindle position and was originally designated spn-3 (http://www.wormbase.org/); a single spn-3 allele was obtained from ∼10,000 haploid genomes screened (Rose and Kemphues, 1998; Tsou and Rose, unpublished results). Mapping experiments placed it150 between sma-3 and cyk-1, and it150 was complemented by the deletions sDf125 and sDf135, but not sDf127. Complementation tests with lethal and maternal effect mutations mapping to this deletion interval (Stewart et al., 1998; Swan et al., 1998; Kurz et al., 2002); see strains above) were carried out. The let-711(s2587) mutation and three other let-711 mutations failed to complement it150 as shown for s2587 in Table 1, whereas all other mutations tested complemented. To generate s2587/it150 mutants for all further experiments, RL67 males were mated to RL93 hermaphrodites, and Unc hermaphrodites (dpy-17 s2587 unc-32/it150 unc-32) were chosen. The phenotype of it150/s2587 derived embryos varied with temperature as shown in Table 1; worms raised at 13–15°C were used for all further analyses, and their embryos were examined within 2 d after L4 stage because older worms produced very few fertilized embryos. Although care was taken to minimize the time worms were at room temperature during collection and preparation for both live and fixed analyses, filming had to be carried at room temperature (23–25°C). However, the shift in temperature during filming did not obviously affect the phenotype: the same spindle positioning defects were observed in embryos that were filmed for the first cell cycle at room temperature as were seen in embryos directly cut from mothers (who were thus at 13–15°C up until division). it150/s2587 hermaphrodites mated to CB4856 males (which leave a mucus plug indicating successful mating) produced dead embryos (progeny from 10 matings examined); such embryos had a phenotype identical to those produced by unmated hermaphrodites (n = 13 embryos filmed), indicating that the division phenotype and lethality are maternal effects of the mutations.

Table 1.

Phenotypes of let-711 mutants

| Genotypea | Temp (°C)b | nc | Embryonic lethality (%)d | Embryonic phenotypese |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wild type | 14 | 5 | 0.8 ± 0.8 | Normal spindle positioning |

| unc-32 | 14 | 9 | 4.5 ± 7.4 | Normal spindle positioning |

| unc-32 | 25 | 7 | 0.4 ± 0.4 | Normal spindle positioning |

| let-711(s2587)/qCl | 14 | 4 | 2.8 ± 2.2 | Normal spindle positioning |

| 20 | 10 | 2.0 ± 0.9 | Normal spindle positioning | |

| let-711(it150)/let-711(it150) | 16 | 9 | 47.5 ± 24.5 | Weak spindle positioning defects |

| 25 | 51 (1) | 72.3 ± 17.7 | Weak spindle positioning defects | |

| let-711(it150)/let-711(s2587) | 14 | 10 (1) | 100 ± 0.0 | Strong spindle positioning defects |

| 16 | 17 (3) | 100 ± 0.0 | Strong spindle positioning defects | |

| 20 | 16 (6) | 100 ± 0.0 | Strong spindle positioning defects | |

| 25 | 20 (11) | 100 ± 0.0 | No development |

a Both wild-type and unc-32 worms were tested, because all combinations of let-711 alleles were marked with unc-32 (see Materials and Methods for complete strain descriptions).

b Temperature at which hermaphrodites were raised (±1°C).

c Number of hermaphrodites whose embryos were scored for hatching, with the number of hermaphrodites that laid no embryos shown in parentheses.

d The percentage of embryos that failed to hatch, given as the mean ± SD per hermaphrodite (does not include sterile hermaphrodites).

e Of embryos produced by it150 homozygotes shifted to 25°C for 24 h after L4 stage, 2 of 28 1-cell embryos exhibited failure of nuclear rotation, and in an additional 6 of 28 the spindle skewed laterally or toward the posterior during anaphase; 4 of the remaining embryos showed a failure of P1 nuclear rotation at second division. In embryos from worms raised at 25°C continuously, a higher penetrance of first spindle positioning defects was observed, but the worms showed greatly reduced embryo production, making analysis difficult. All embryos produced by it150/s2587 mothers raised at 13–20°C showed defects at first division similar to those described in the text and Table 2; the embryos were also osmotically sensitive, and this defect was worse at higher temperatures. it150/s2587 worms raised at 25°C were usually sterile, but 9 produced <20 embryos that were extremely osmotically sensitive and never showed signs of development.

RNAi of zyg-9

Antisense and sense RNAs were transcribed in vitro (Ambion, Austin, TX; Megascript) from a PCR-derived zyg-9 DNA template, which consisted of a 1-kb genomic fragment of zyg-9 with T3 (ggaaggtggatatccttcccaaacttccacc) or T7 (ggatttcagcaatctctgcgggcccagc) promoters appended at either end. Double-stranded RNAs (dsRNA) were annealed as described (Fire et al., 1998). L4 worms were soaked (Tabara et al., 1998) in zyg-9 dsRNA solution (1.5 mg/ml) for 13–15 h at 13–15°C, and the progeny of soaked worms were analyzed beginning at 24 h after soaking. The time at which zyg-9(RNAi) embryos showed fully penetrant defects in migration and rotation varied slightly with different preparations of RNAi; thus for each experiment wild-type and let-711 embryos were soaked in the same preparation of dsRNA, and let-711;zyg-9(RNAi) embryos were always examined at the time when the zyg-9(RNAi) embryos began showing the strong phenotype reported in Table 1.

Microscopy and Analysis of Living Embryos

For live analysis, embryos were cut from hermaphrodites in egg buffer (due to osmotic sensitivity of some let-711 embryos; Edgar, 1995) and mounted on poly-lysine–coated slides as described (Rose and Kemphues, 1998) to prevent flattening. Mounted embryos were filmed under DIC optics using time-lapse videomicroscopy. Embryos were examined from pronuclear migration through first division, and the position of pronuclei at meeting, centration, and rotation were scored from the video images. The degree of rotation was scored at nuclear envelope break down, before cell shape can alter the orientation, and spindle position was scored at metaphase (just before spindle poles began moving apart) and late anaphase (as judged by ingression of the cleavage furrow).

Immunolocalization and Quantification of Centrosome-staining Intensities

For in situ immunolocalization, worms were cut in egg buffer on poly-lysine–coated slides, freeze-fractured, and fixed in −20°C methanol (Miller and Shakes, 1995). Slides were preblocked with 30% goat serum for 15 min at room temperature, and primary antibody incubations were carried out as described for PAR-3 (1:40 in PBS; Etemad-Moghadam et al., 1995), P granules (MabOIC1D4, 1:2; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, developed by Strome and Wood, 1983), and ZYG-9 (1:25; (Matthews et al., 1998), and AIR-1 (1:50; Schumacher et al., 1998), followed by secondary antibody incubation at room temperature for 1–2 h with FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse (1:100 in PBS, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). For α-tubulin localization, slides were fixed in room temperature methanol for 5 min and incubated with DM1a (1:400 in PBS; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 45 min at room temperature, followed by secondary antibody incubation. Embryos were staged by DAPI (4′,6-diamindino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride; Sigma) staining of the DNA. Specimens were mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Images of stained embryos were obtained using either a 100× UPlanFl NA 1.30 Olympus Photomicrocope BX60 (Melville, NY) equipped with a Hamamatsu Orca CCD camera (Bridgewater, NJ), a 100× HcxPlApo NA 1.40 objective on a Leica Confocal (Deerfield, IL; type TCS SP) microscope, or a 60× PlanApo NA 1.42 objective on an Olympus FV1000 Fluoview Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope. For confocal microscopy, z series (0.24-μm optical sections) through the entire embryo were obtained. For epifluorescence microscopy, midcentrosome focal plane images were taken for each centrosome.

For confocal images used in quantifying centrosome staining, all images were taken with identical settings, with the gain adjusted below saturation. A single section at midcentrosome was examined. Using ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij), the mean pixel intensities were measured in a circle of fixed size placed over the centrosome. The size was chosen such that the entire brightly staining centrosome was contained within the circle from pronuclear meeting through anaphase for ZYG-9 (4.89 μm in diameter). For AIR-1, the same size circle was used for meeting through metaphase, but was increased at anaphase (7.11 μm) to accommodate the greater area stained by this antigen at this stage. For both antigens, cytoplasmic intensities were measured from a circle of 10 μm placed in the anterior half of the embryo, away from the centrosomes.

To quantify γ-tubulin accumulation, a let-711(it150) unc-32/qC1; γ-tub:GFP strain was created from RL67 and OD44. Males from this new strain were crossed to dpy-17 let-711(s2587) unc-32/qC1 hermaphrodites or to unc-32 hermaphrodites. The unc-32 progeny from each cross (it150/s2587 and it150/+ respectively) were examined. At pronuclear meeting, NEB, and metaphase, as judged by brightfield microscopy (∼3-min intervals), epifluorescence images of each centrosome at a midfocal plane were obtained (two images per time point at identical settings below saturation). Staining intensity was quantified as described above for ZYG-9, except that the circle size was 3.3 μm.

Quantification of Microtubule Numbers, Depolymerization, and Regrowth Experiments

Embryos were processed for immunofluorescence of microtubules and examined by confocal microscopy as described above. For these experiments the gain was adjusted such that microtubule-staining intensity appeared similar in each embryo. Although this precludes comparison of absolute staining intensity between embryos, it allowed for more consistent identification of “microtubule bundles” from embryo to embryo. To count the number of microtubules bundles extending from the centrosome, two 0.24-μm optical sections taken at a midcentrosome focal plane from each embryo were merged and analyzed using Openlab software (Improvision, Lexington, MA). Because astral microtubules are excluded by the nucleus, only microtubules emanating from the nonnuclear half of the aster were counted for each embryo. The width and pixel intensity of all microtubule line segments reaching a specific distance from the center of the centrosome (8 or 10 μm) were measured. Counting absolute numbers of microtubules in light microscope images is resolution limited such that a bundle of 2 or more microtubules will appear to have the same width as a single microtubule. A bundle of two microtubules, however, will have twice the staining intensity as a single microtubule in the same image. To partially correct for this problem, we assumed that the dimmest anti-tubulin staining line segments in any image represented single microtubules. The average intensities of the five dimmest line segments in each image were therefore used to define a “single microtubule,” and any line segments with twice this intensity were scored as two microtubules. Similarly, line segments greater than two times the average width of the standards were scored as two microtubules; the smallest measurable line segment in most embryos was ∼2 pixels or 0.25 μm, which is reasonable for the resolution limit of the objective used. The values for all line segments were then added together to obtain the number of microtubules for each half centrosome. Microtubule numbers change during mitosis (Hannak et al., 2001, 2002), so only wild-type embryos from pronuclear meeting through centration/rotation (not including nuclear envelope breakdown) were grouped for this analysis; for mutants with defects in these events, similar late prophase stages were chosen based on DAPI staining. With the exception of zyg-9(RNAi), embryos in which the centrosomes were very close to the posterior were excluded from this analysis if the 8-μm distance was outside the embryo for any part of the half centrosome, because this could result in an artificially low count. For zyg-9(RNAi) embryos, most centrosomes would have been excluded by this criterion, and thus instead, microtubules were counted for each quarter centrosome and the number was multiplied by 2 for comparison in Table 2. For practical reasons, the wild-type controls done in parallel with the mutants for this experiment were grown at 20°C, and all mutants were grown at 13–15°C. Examination of wild-type embryos grown at 13–15°C gave similar results; for example, 18.2 ± 4.2 microtubules per centrosome extended 10 μm (n = 6).

Table 2.

Nuclear and centrosome positions in 1-cell embryos

| Genotype | Position of pronuclear meetinga | Position of pronuclei at NEBb | Angle of centrosomes at NEB (°)c | Angle of centrosomes at metaphase (°)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type (n = 13) | 66.4 ± 6.3 | 51.7 ± 3.8 | 18.0 ± 10.9 | 7.0 ± 5.7 |

| let-711 (n = 17) | 76.8 ± 5.0 | 65.0 ± 10.5 | 64.4 ± 19.3 | 56.9 ± 20.9 |

| zyg-9(RNAi) (n = 12) | na | 81.9 ± 4.5 | 73.1 ± 18.5 | 71.6 ± 18.6 |

| let-711;zyg-9(RNAi) (n = 13) | 68.7 ± 8.8 | 56.2 ± 10.9 | 38.5 ± 26.5 | 23.5 ± 25.2 |

All values given are mean ± SD for the number of embryos scored (n) for each genotype.

a Position of midpoint between the pronuclei at meeting, expressed as percentage (%) of egg length, with anterior equal to 0%. This parameter was measured for only 10 let-711 embryos and 10 let-711;zyg-9 embryos, because either the maternal pronucleus was initially located in the posterior end (see text), which could result in premature meeting, or the pronuclei had already met at the time filming started. In zyg-9 embryos, the female and male pronuclei do not meet during prophase, and so this measurement is not applicable (na).

b Position of the center of the pronuclei, expressed as percentage (%) of egg length, just after nuclear envelope breakdown (NEB).

c Angle of a line drawn through both centrosomes, relative to the anterior/posterior axis (0°). Wild-type embryos showed a range of angles from 0 to 39° at NEB (12/13 spindles had rotated to within 30°). Only 3/17 let-711 spindles and 0/12 zyg-9 spindles were within this wild-type range, but 8/12 let-711;zyg-9embryos were within the wild-type range.

Microtubule depolymerization by cold treatment was carried out using a modification of the protocol described by Hannak et al. (2002). Worms were cut in egg buffer on poly-lysine–coated slides and placed on an aluminum block in an ice bath (0–1°C) for 5, 30, or 60 min to allow microtubule depolymerization. Slides were then transferred to an aluminum block at 4°C for 0, 10, or 20 s and then transferred to liquid nitrogen, followed by processing for immunofluorescence. Regrowth was carried out at 4°C instead of room temperature to reduce the number of microtubules and thus allow for quantification of both number and length. The microtubules were quantified as above, except that line segments extending from the entire centrosomal region were included, and the length of each microtubule and microtubule bundle from the center of the centrosome was also measured.

Molecular Identification of LET-711

To map let-711 using single nucleotide polymorphisms present between the Bristol and Hawaiian strains of C. elegans (Wicks et al., 2001), RL116: sma-3 let-711(s2587) unc-32/qC1 hermaphrodites (Bristol) were mated to CB4856 (Hawaiian) males to generate heterozygotes, and the sma-3 let-711(+) recombinants were analyzed for the presence of SNP-T07E3[1], SNP-F57B9[1], and SNP-pk3076[1] (http://www.wormbase.org/). Of 7 recombinants, 3 recombined between sma-3 and SNP-T07E3[1] and 4 recombined between SNP-T07E3[1] and SNP-F57B9[1], suggesting that let-711 was to the right or very close to SNP-F57B9[1]. Genomic DNA was prepared from let-711(s2587) arrested larvae and was PCR amplified, and the coding region, and introns of the following predicted genes (spanning most of the region between SNP-T0E3[1] and SNP-F57B9[1]) were sequenced: F57B9.1, F57B9.2, F57B9.3, F57B9.4, F57B9.5, F57B9.6, F57B9.7, F57B9.8, F57B9.9, F57B9.10, F31E3.1, F31E3.2, F31E3.3, F31E3.4, and F31E3.5. A DNA change that would produce an amino acid change in s2587 was found in F57B9.2. The F57B9.2 region (the entire 13 kb between adjacent genes F57B9.9 and F57B9.10) was sequenced in its entirety from s2587 and the other let-711 alleles. All errors were confirmed by sequencing two additional independent PCR reactions. The DNA changes for each allele were as follows: s2587, C6711T (resulting in Q1053stop); s2473, C4266T and C9346T (L630F, Q1878stop); s2790, C10862T (Q2362stop); and it150, G8280A, which changes the 3′ acceptor splice site of intron 15. As controls, the entire region was also sequenced from let-771(s2442), which was isolated in the same background as the let-711 alleles (Stewart et al., 1998), and KK93, the it150 background. The only change compared with the Genome Consortium Sequence was a base addition (3871T) in intron 9 that was present in both controls and all let-711 alleles.

For RNAi of F57B9.2, a bacterial clone from the Ahringer RNAi library (Kamath et al., 2003) was used for feeding experiments (Timmons et al., 2001). An overnight culture of this bacteria alone or mixed 1:1 with control bacteria (L4440, vector only) were plated on MYOB/IPTG/Amp plates and allowed to dry overnight at room temperature. Wild-type L4 worms were then plated, and their embryos were examined 18–30 h after the start of exposure.

RESULTS

let-711 Mutant Embryos Have Defects in Centration and Rotation of the Nuclear–Centrosome Complex

The it150 mutation was identified in screens for maternal effect lethal mutations that cause defects in spindle positioning during the first cleavage divisions of the C. elegans embryo (Rose and Kemphues, 1998). The it150 allele behaves as a recessive temperature-sensitive maternal effect lethal mutation, but after outcrossing produces only weak defects in spindle orientation (Table 1). Mapping and complementation tests revealed that it150 is an allele of the let-711 gene (Table 1 and Materials and Methods). Four let-711 alleles, including the s2587 mutation, were previously identified (Stewart et al., 1998); all are homozygous lethal at the early or midlarval stage, and the s2587 allele shows the same early larval arrest in trans to the deletion sDf127 (Stewart et al., 1998). In contrast, worms heterozygous for the it150 mutation and let-711(s2587) raised at 16–20°C were viable but produced osmotically sensitive embryos that failed to hatch (Table 1). Such heteroallelic hermaphrodites raised at 25°C were either sterile or produced <20 embryos (Table 1). Examination of the germ lines of the sterile it150/s2587 worms revealed oocytes of various sizes packed together in a disorganized manner. Together these results suggest that s2587 is a strong or complete loss-of-function allele, that the it150 mutation is a rare maternal allele of let-711, and that the let-711 gene is required for several different aspects of development.

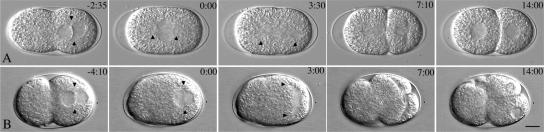

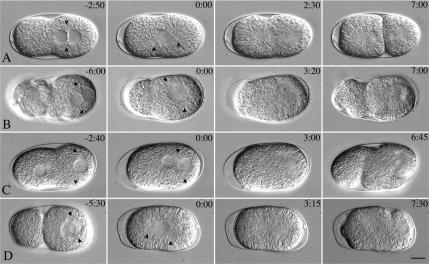

We found that the embryos produced by heteroallelic s2587/it150 worms raised at 13–15°C were less osmotically sensitive than those raised at 16–20°C, but gave a similar strong spindle-positioning phenotype. Such embryos were used for all further analysis and will be referred to hereafter as let-711 embryos. We first examined let-711 embryos by time-lapse videomicroscopy and compared them with wild-type embryos (Figure 1; representative data sets are shown in Table 2). In wild-type embryos meiosis is completed after fertilization, and results in the formation of two polar bodies and a single female pronucleus. The female pronucleus is typically located at opposite end of the embryo from the sperm pronucleus, whose position determines the posterior pole of the embryo. After pronuclear formation, the plasma membrane undergoes a series of anterior cortical contractions that culminate in a single pseudocleavage furrow. The furrow recedes as the female pronucleus migrates from the anterior to meet the male pronucleus near the posterior pole (pronuclear meeting). Together the pronuclei and associated centrosomes move to the center of the embryo (centration) and the centrosomes rotate 90° onto the anterior/posterior axis (nuclear rotation), usually before nuclear envelope breakdown (12/13 wild-type embryos in Table 2; Figure 1A). At metaphase/anaphase, the spindle moves toward the posterior and elongates more toward the posterior, such that first cleavage is unequal (Labbe et al., 2004). In let-711embryos after meiosis, anterior cortical contractions and pseudocleavage furrows formed; a single female pronucleus was observed, suggesting that the previous meiotic divisions proceeded normally (n = 17). In some let-711 embryos (2/12 embryos from Table 2 that could be scored before pronuclear meeting), the female pronucleus was located at the same pole as the sperm nucleus. In the remaining embryos in which the female pronucleus was anteriorly located, migration of the female pronucleus occurred and the pronuclei met in the posterior (Figure 1B), but at a position slightly more posterior than in wild-type embryos (Table 2). The most striking defects in let-711 embryos were seen during nuclear and spindle positioning (Figure 1B). In most embryos, the pronuclei failed to center completely (11/17), failed to undergo a full 90° nuclear rotation before nuclear envelope breakdown (14/17), or both (Figure 1). These defects resulted in spindles setting up at an angle and farther to the posterior on average than in wild type. Abnormal spindle orientations persisted through metaphase and anaphase in most embryos. Thus, in many embryos (11/17) the cytokinesis furrow initiated from a posterior or a lateral posterior position, and ectopic furrows formed in the anterior of the embryo (Figure 1B). In the remaining embryos, the anaphase spindle skewed closer to one cortex (2/17), or the entire spindle and the embryo rotated within the eggshell such that the final spindle position was abnormal (2/17); in these cases, the cytokinesis furrow initiated at an abnormal location and was also accompanied by ectopic furrows. In most embryos the furrows resolved to produce 2-cell embryos with variably sized cells; however, in ∼30% of embryos all furrows receded, resulting in one cell that divided with a multipolar spindle at the next division.

Figure 1.

let-711 embryos have defects in centration and nuclear rotation. Time-lapse DIC microscopy series of wild-type (A) and let-711 mutant embryos (B). Each series consists of 1-cell embryos at pronuclear meeting, nuclear envelope breakdown, anaphase, telophase, and 2-cell prophase. Time is indicated (minutes:seconds) for each image, relative to nuclear envelope breakdown equals 0:00. Arrowheads indicate the position of centrosomes. Scale bar, 10 μm.

To determine if let-711 embryos had defects in overall cellular polarity that could cause the spindle-positioning defects, we compared the localization of polarity markers in let-711 and wild-type embryos. P granules were localized normally in 20/22 1-cell let-711 embryos (compared with 29/30 wild-type embryos; Strome and Wood, 1983). In addition, PAR-3 was localized at the anterior cortex in 30/31 let-711 embryos examined, as in wild type (23/23 embryos; Etemad-Moghadam et al., 1995). Thus polarized proteins are properly localized in 1-cell mutant embryos at the time of nuclear rotation, suggesting that LET-711 functions downstream of polarity establishment or in a parallel pathway to orient the spindle.

let-711 Embryos Have Longer and More Cold-stable Microtubules than Wild Type

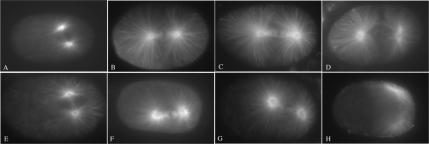

Mutations in zyg-8 and zyg-9, as well as treatment with nocodazole, result in shorter than normal microtubules and produce defects in centration and anaphase spindle positioning (Hyman and White, 1987; Matthews et al., 1998; Gonczy et al., 2001). We therefore compared wild-type and let-711 embryos fixed and stained with antibodies against α-tubulin to examine microtubule length. Surprisingly, let-711 embryos had robust microtubule asters, similar to those of wild type, and some embryos appeared to have more long microtubules reaching the cortex (Figure 2 and see below). In addition, the densely staining area of microtubules at the centrosome appeared larger in let-711 embryos compared with wild type. During mitosis, the centrosome matures and nucleates more microtubules and expands in diameter as the cell cycle proceeds (Hannak et al., 2001, 2002). In wild-type embryos, the densely staining region in the middle of the centrosome appeared circular during prophase and ring-like during metaphase and anaphase and then became dispersed during telophase (Figure 2, A–D). In let-711 embryos, the centrosomes already appeared ring-like during prophase and appeared to expand to a greater diameter in metaphase and anaphase compared with wild type (Figure 2, E–H, more than 5 embryos examined each stage). In anaphase and telophase let-711 embryos in which the spindle was transversely oriented, the centrosomes also appeared extended along the cortex (Figure 2H). However, in 2-cell embryos, the centrosomes once again appeared as small circles or ring-like structures that then expanded as the cell cycle progressed (unpublished data).

Figure 2.

let-711 embryos have robust asters and expanded centrosome morphology. Epifluorescence images of wild-type (A–D) and let-711 mutant embryos (E–H) stained for α-tubulin. One-cell embryos at prophase (A and E), metaphase (B and F), anaphase (C and G), and telophase (D and H) are shown. Although most let-711 embryos at metaphase and anaphase had more severely mispositioned spindles than these examples, these more clearly illustrate the altered centrosome size using a single focal plane image. The telophase embryo illustrates the abnormal extension of centrosomes along the cortex that occurs in anaphase and telophase let-711 mutants in which the spindle is posteriorly positioned. Note that exposure and gain settings were used that allowed visualization of the hollow center of centrosomes, and thus astral microtubules are less distinct compared with the images in Figure 3. Scale bar, 10 μm.

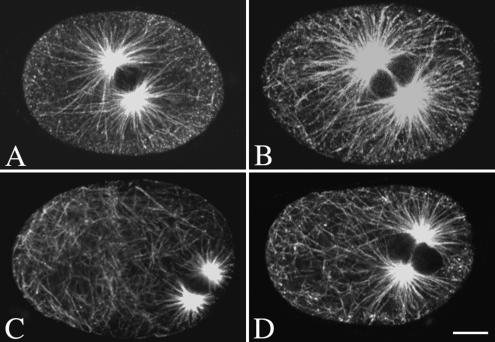

To quantify changes in microtubule length in let-711 embryos, we first examined the microtubules contacting the cortex in confocal images of embryos. Although some let-711 embryos had more microtubules contacting the cortex (Figure 3and unpublished data), the posterior position of the pronuclei in let-711 embryos could result in more cortical contacts even if overall microtubule length was the same as in wild type. In addition, accurate counts of the number of astral microtubules reaching the anterior cortex were difficult because of the variable number of noncentrosomal microtubules still present at this stage in both let-711 and wild-type embryos. We therefore quantified the number of microtubules extending at least 8 or 10 μm from the centrosome in late prophase embryos, the time during which the defects in centration and rotation occur in let-711 embryos. For each embryo, the number of microtubule line segments reaching a certain distance was measured using optical confocal sections taken through the middle of the centrosome; this raw count was normalized for the width and staining intensity of each line segment to calculate the number of microtubules per centrosome (Table 3; see Materials and Methods). On average, let-711 embryos had more microtubules extending from the centrosome than wild-type embryos for both distances (Table 3). These data indicate that a reduction in LET-711 function increases the number of long astral microtubules.

Figure 3.

Microtubules are longer in let-711 embryos. Confocal images of wild-type (A), let-711 (B), zyg-9(RNAi) (C), and let-711;zyg-9(RNAi) (D) embryos stained for α-tubulin. Each image is a projection of two optical sections through the middle of the centrosomes; exposure and gain settings were adjusted to allow visualization of microtubules extending to the cortex. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Table 3.

Quantification of astral microtubules in 1-cell prophase embryos

| Genotype | n | Microtubules per centrosome extending 8 μm | Microtubules per centrosome extending 10 μm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 12 | 25.6 ± 5.0 | 22.7 ± 4.6 |

| let-711 | 8 | 39.5 ± 8.8 | 36.0 ± 6.6 |

| zyg-9(RNAi) | 28 | 1.9 ± 3.4 | 0.8 ± 1.8 |

| let-711; zyg-9(RNAi) | 8 | 38.0 ± 6.9 | 33.1 ± 9.1 |

Number of microtubules (mean ± SD) extending the indicated distance from the center of a centrosome, taking both width of line segments and intensity into account, as described in Materials and Methods. Only microtubules on the half of the centrosome facing away from the nucleus were counted; the number of half centrosomes (n) examined for each genotype is given.

To determine if the greater number of long microtubules in let-711 embryos correlates with a change in microtubule stability, embryos were subjected to cold treatment (Hannak et al., 2002). As was reported previously, wild-type embryos incubated at 0–1°C for 5 min had virtually no astral microtubules (Figure 4A; Hannak et al., 2002; Bellanger and Gonczy, 2003). However, after 5 min at 0–1°C, let-711 embryos had significantly more long microtubules extending from the centrosome than wild-type embryos (Figure 4E). This subset of cold-stable microtubules did not appear to decrease at 10 and 30 min (unpublished data); however, let-711 embryos incubated at 0°C for 60 min had the same number of microtubules remaining as wild type (Figure 4, B and F, and Table 4).

Figure 4.

Microtubules are more cold-stable in let-711 mutant embryos. Confocal images of wild-type (A–D), let-711 (E–H), and zyg-9(RNAi) (I–L) embryos mutant embryos after cold treatment and regrowth. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Table 4.

Quantification of astral microtubules after cold treatment and regrowth

| Genotype | Time of regrowth (s) | na | Microtubules per centrosomeb | Length of microtubules (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 0 | 18 | 2.5 ± 2.2 | 1.8 ± 0.2 |

| 10 | 20 | 4.3 ± 1.7 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | |

| 20 | 20 | 9.3 ± 4.2 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | |

| let-711 | 0 | 14 | 2.6 ± 2.4 | 2.0 ± 0.1 |

| 10 | 18 | 19.8 ± 7.2 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | |

| 20 | 20 | 26.3 ± 5.2 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | |

| zyg-9(RNAi) | 0 | 20 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.2 |

| 10 | 22 | 1.2 ± 1.4 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | |

| 20 | 20 | 1.7 ± 2.5 | 2.0 ± 0.2 |

Embryos of the given genotype were subjected to cold treatment for 60 min, followed by regrowth for the times indicated.

a Number of centrosomes examined for each genotype.

b Average number of microtubules (mean ± SD) extending from the center of a centrosome.

c Average length of microtubules (mean ± SD) extending from the center of a centrosome.

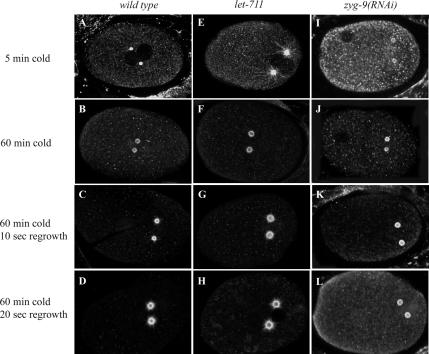

The cold stability of microtubules in let-711 embryos could be due to an increase in stability in a subset of let-711 astral microtubules, or let-711 embryos could nucleate more microtubules in general, allowing a larger number to remain stable under these conditions. To assay for microtubule nucleation, we carried out regrowth assays (Hannak et al., 2002). Embryos were incubated for 60 min at 0–1°C to depolymerize most of the astral microtubules as described above. Embryos were then shifted to 3–4°C for 10 or 20 s to allow regrowth of microtubules and then fixed, stained., and analyzed for astral microtubule length and number (Figure 4, C, D, G, and H; Table 4). Analysis of astral microtubules after 10 s of regrowth at 4°C showed let-711 embryos to have significantly more microtubules with a longer average length than wild type. To obtain an indirect measure of microtubule polymerization rate in these embryos, we compared the number and length of microtubules after regrowth at 10 and 20 s. After 20 s of regrowth at 3–4°C, let-711 embryos continued to have more microtubules with a longer average length than wild-type embryos. However, between 10 and 20 s of regrowth the wild-type embryos had an increase of ∼5 microtubules per embryo and an increase in length of 0.7 μm per microtubule, whereas let-711 embryos had an increase of 6.5 microtubules per embryo and 0.4 μm per microtubule. Thus, the reduction of LET-711 affected the initial nucleation rate during regrowth, but did not increase continued nucleation or polymerization rate. These results suggest that reduction of let-711 activity may not affect nucleation rate under physiological conditions, but rather that in let-711 mutant embryos more microtubule seeds remain after cold treatment compared with wild type, even at long treatment times. Thus, we propose that the longer microtubules in untreated let-711 embryos are due to a change in microtubule dynamics other than polymerization rate or nucleation rate. Such changes in microtubule dynamics, the resulting longer microtubules, or both could then interfere with the normal cortical interactions necessary for centration and rotation.

Simultaneous Reduction of let-711 and zyg-9 Results in Less Severe Spindle Positioning Defects

The phenotype of let-711 embryos is opposite to that seen in zyg-9 loss of function embryos, which have astral microtubules that are shorter than wild type (Kemphues et al., 1986; Matthews et al., 1998). Thus, we hypothesized that wild-type LET-711 may function in opposition to ZYG-9. We examined let-711;zyg-9 double mutant embryos to determine if reduction of LET-711 could suppress the zyg-9 phenotype or vice versa, using zyg-9(RNAi) to reduce the function of zyg-9 in the let-711 heteroallelic background. As a baseline for comparison, we first examined wild-type worms soaked in zyg-9 dsRNA. In zyg-9(RNAi) embryos examined by time-lapse videomicroscopy from 24 to 40 h after treatment, we observed defects in meiosis and mitosis that were similar to those previously described for zyg-9 strong loss-of-function mutations (Kemphues et al., 1986; Matthews et al., 1998). Instead of two polar bodies and a single female pronucleus as seen in all wild-type embryos (n = 13), some zyg-9(RNAi) embryos were missing one or both polar bodies and had more than one female pronucleus, indicating a defect in meiosis (n = 4/12). In zyg-9(RNAi) embryos, the female pronucleus did not migrate normally and thus the female and male pronuclei did not meet until prometaphase or later (n = 11/12; Figure 5C), whereas pronuclear meeting always occurred during prophase in wild-type embryos (n = 13; Figure 5A). In addition, all zyg-9(RNAi) embryos had defects in centration and rotation, resulting in spindles being set up in the posterior and on the wrong axis compared with wild type (Figure 5C and Table 2). In contrast, fewer let-711;zyg-9(RNAi) embryos examined during the same time period were defective in meiosis, as judged by the appearance of two polar bodies and one female pronucleus (11/12), and the male and female pronuclei met during prophase in the posterior of all such embryos (Figure 5D and Table 2). In addition, in let-711;zyg-9(RNAi) embryos the pronuclei moved to the center of the embryo and rotated to an extent that was on average more like wild type than either single mutant alone (Figure 5D and Table 2). The orientation of metaphase and anaphase spindles was also normal in a higher percentage of double mutant embryos, but in some embryos spindles skewed toward the cortex in late anaphase/telophase (Figure 5D) and division was accompanied by ectopic furrowing. Although spindle positioning was more like wild type in these embryos, they nonetheless failed to hatch.

Figure 5.

Simultaneous reduction of let-711 and zyg-9 restores centration and rotation. Time-lapse videomicroscopy series of wild-type and mutant embryos during first division. A wild-type embryo (A) is shown from pronuclear meeting through early anaphase; a let-711 embryo (B), a zyg-9(RNAi) embryo (C), and a let-711;zyg-9(RNAi) (D) embryo at comparable stages are shown. Time is indicated (minutes:seconds) for each image, relative to nuclear envelope breakdown equals 0:00. Arrowheads indicate the position of centrosomes. Scale bar, 10 μm.

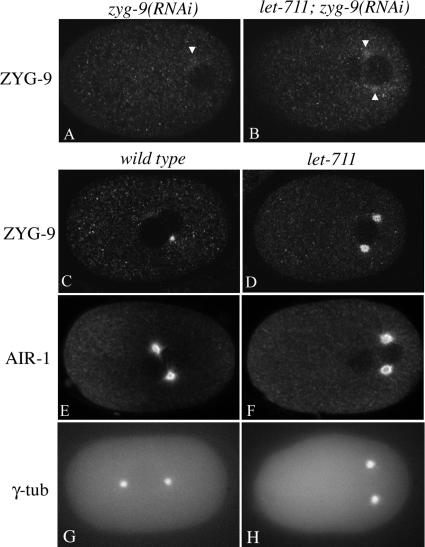

In let-711;zyg-9(RNAi) embryos examined at later time points after RNAi treatment, the phenotype observed by time-lapse videomicroscopy became increasingly more like zyg-9, and embryos exhibited complete failures of centration and nuclear rotation (n = >10), which suggests that at the time mutual suppression was observed, some ZYG-9 activity remained. Consistent with this, when embryos from the same time point were stained for ZYG-9 protein (Figure 6, A and B), many let-711;zyg-9(RNAi) embryos showed residual ZYG-9 staining at the centrosome (e.g., 7/9 prophase embryos in one data set). However, ZYG-9 staining in these let-711;zyg-9(RNAi) embryos was greatly reduced compared with that in both wild-type and let-711 embryos (Figure 6 C and D), and some let-711;zyg-9(RNAi) embryos showed no detectable ZYG-9 (2/9 embryos). In addition, zyg-9(RNAi) embryos from the same time points consistently showed less ZYG-9 remaining at the centrosome (Figure 6A) than the let-711;zyg-9(RNAi) embryos (3/14 zyg-9(RNAi) prophase embryos showed a slight haze at centrosomes, and 11/14 had no detectable ZYG-9). Although the residual ZYG-9 remaining in let-711;zyg-9(RNAi) embryos can explain the suppression of the zyg-9 phenotype observed in let-711;zyg-9(RNAi) embryos, this result cannot account for the partial rescue of the let-711 phenotype in let-711;zyg-9(RNAi) embryos. Thus, these data show that a partial reduction of both genes' activities can result in mutual suppression of the mutant phenotypes, whereas a stronger loss of zyg-9 function is epistatic to the let-711 phenotype. These results are consistent with let-711 and zyg-9 functioning in a common pathway to regulate microtubule length.

Figure 6.

Localization of ZYG-9 in wild-type and mutant embryos. Confocal images of embryos stained for ZYG-9 (A–D) or AIR-1 (E and F) or epifluorescence images of γ-tubulin:GFP expressing embryos (G and H). Genotypes are as shown; each pair of embryos is age matched (either late prophase or prometaphase). The positions of the centrosomes (white arrowheads) in zyg-9(RNAi) and let-711; zyg-9(RNAi) were determined from double-staining for tubulin. Note that only one centrosome is fully in the focal plane for A and C. For each protein analyzed, the images were taken at the same gain and exposure settings and thus intensities can be compared. Scale bar, 10 μm.

To determine if the more normal phenotype seen in let-711;zyg-9(RNAi) double mutants correlated with changes in microtubule length, we examined microtubule length in let-711;zyg-9(RNAi) embryos and zyg-9(RNAi) embryos collected at the time suppression was observed by time-lapse microscopy. Examination of microtubules in zyg-9(RNAi) embryos showed a decrease in the overall length of microtubules compared with wild type, as previously reported, and only rare embryos examined had microtubules reaching 8 μm from the centrosome (Figure 3C and Table 2). In contrast, let-711;zyg-9(RNAi) embryos exhibited many long microtubules extending 8 and 10 μm from the centrosome (Figure 3D and Table 2), consistent with the suppression of the zyg-9 phenotype and the residual amount of ZYG-9 still present under these conditions. Although average microtubule length in let-711 compared with let-711;zyg-9(RNAi) embryos was not dramatically different, it is possible that the number of microtubules actually interacting with the cortex, or their dynamic parameters, were restored to a more wild-type condition in let-711;zyg-9(RNAi), embryos, which then resulted in suppression of the let-711 rotation defect.

We also examined whether the changes in microtubule cold stability and regrowth observed in let-711 embryos are opposite to those in zyg-9(RNAi) embryos. After cold treatment, zyg-9(RNAi) embryos had significantly fewer microtubules extending from their centrosomes than wild-type embryos at all time points (Figure 4, I and J, and Table 4). Similarly, zyg-9(RNAi) embryos had significantly fewer microtubules than wild type after both 10 and 20 s of regrowth at 4°C (Figure 4, K and L, and Table 4). Between 10 and 20 s of regrowth, zyg-9 embryos had an increase of only 0.5 microtubules per embryo and 0.2 μm per microtubule, suggesting that ZYG-9 plays a role in both nucleation and microtubule polymerization, at least under these assay conditions. Thus, LET-711 and ZYG-9 have opposite affects on cold stability and initial nucleation rate. These observations and the suppression of the let-711 phenotype by reduction of ZYG-9 are consistent with the model that let-711 and zyg-9 act in wild-type embryos in opposite ways to promote normal microtubule length and thus spindle positioning. However, because let-711 and zyg-9 mutants did not have opposite effects on continued nucleation or polymerization rate (Table 4), the reduction of let-711 likely affects microtubules in a ZYG-9 independent manner as well.

let-711 Mutant Embryos Have Increased Centrosomal Accumulation of ZYG-9

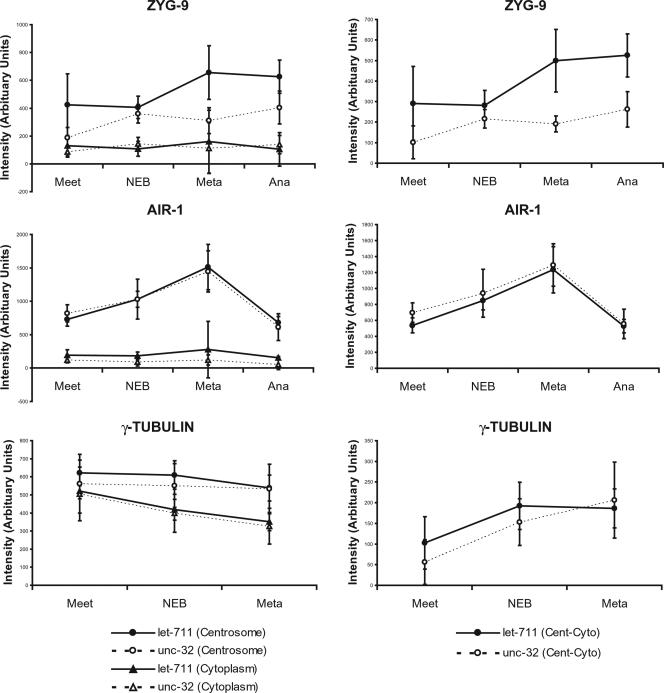

During mitosis the pericentrosomal matrix of proteins grows during a process known as maturation, which allows for an increase in the number of microtubules nucleated from the centrosome. During this time, the appearance of the centrosome visualized with tubulin changes from spherical to ring-like, and the accumulation of components required for centrosome maturation, such as ZYG-9, also increases (Hannak et al., 2001, 2002). Given the genetic interaction with ZYG-9 outlined above and the apparent early expansion of the centrosomes observed with tubulin staining, we more carefully compared the localization of ZYG-9 at the centrosome in wild-type and let-711 single mutant embryos. In let-711 embryos, ZYG-9 localized to the centrosome, and the diameter of the staining increased during the cell cycle as in wild type. However, the diameter of ZYG-9 localization in pronuclear meeting through metaphase stage let-711 embryos appeared larger than controls at the same stages (Figure 6, C and D; n = >20 for each genotype). The increased area of ZYG-9 localization could represent a higher accumulation of antigen, or alternatively, the expansion of the centrosome could spread the wild-type amount of antigen into a larger area. To distinguish between these possibilities, we quantified the average staining intensities of a small area including the centrosome, as well as a fixed area of cytoplasm (Figure 7). The mean intensities of ZYG-9 staining at let-711 centrosomes were greater than wild-type centrosomes at most stages examined, whereas the cytoplasmic intensities of ZYG-9 were similar. These observations indicate that in let-711 embryos, more ZYG-9 accumulates at the centrosome.

Figure 7.

Quantification of staining intensities of ZYG-9, AIR-1, and γ-tubulin::GFP. Each plot on the left shows the cytoplasmic and centrosomal staining intensities for a single antigen in wild-type and let-711 embryos at pronuclear meeting (Meet), nuclear envelope breakdown/prometaphase (NEB), metaphase (Meta) and anaphase (Ana). Values are mean intensities; error bars indicate the SEM at the 95% confidence level. Intensities for ZYG-9 and AIR-1 were determined from fixed samples: n = 6–22 centrosomes for each genotype at each stage (except n = 4 for let-711, ZYG-9 anaphase). Intensities for γ-tubulin were determined from living embryos expressing γ-tubulin::GFP (n = 2 centrosomes each from 7 let-711 and 5 wild-type embryos); the decrease in γ-tubulin::GFP intensities over time was due to bleaching. The ZYG-9 metaphase value is statistically different between let-711 and wild type at this confidence level, and calculation of the 90% confidence level gives significant differences for ZYG-9 during meeting and anaphase as well. All other values are not statistically different between let-711 and controls. For these measurements, the mean intensity of a circle of fixed size was used (see Materials and Methods for details) to compare centrosomes. Because this measure is proportional to the total intensity in a given area, this allows determination of whether a larger total amount is present or whether the wild-type amount is distributed in a larger area at let-711 centrosomes. This method includes some cytoplasmic signal, which could artificially lower the centrosomal value, especially for controls with smaller diameters of ZYG-9 staining. The right-hand panels show plots of the data where the cytoplasmic levels (Cyto) were subtracted from the centrosome levels (Cent). Using this measure, ZYG-9 intensities in let-711 are still significantly different from wild type (SEM, 95% confidence level) except at NEB.

In wild-type embryos, the cell cycle–dependent increase in localization of ZYG-9 to the pericentriolar region depends on the activity of AIR-1 and γ-tubulin, key components of the maturation process (Hannak et al., 2002). We therefore examined the localization of these proteins in let-711 embryos. In wild-type and let-711 embryos fixed and stained with AIR-1 antibodies, AIR-1 localized strongly to centrosomes and weakly to microtubules (Schumacher et al., 1998; Hannak et al., 2002; Figure 6). Quantification of staining intensities did not reveal any significant differences between wild type and let-711 at any stage for either cytoplasmic or centrosomal accumulation of AIR-1 (Figure 7). This suggests that in contrast to the result for ZYG-9, let-711 centrosomes do not contain more AIR-1 protein. To quantify γ-tubulin levels, a γ-tubulin::GFP reporter under the regulation of pie-1 regulatory sequences was used. The cytoplasmic and centrosomal intensities of γ-tubulin::GFP in let-711 embryos were similar to those in wild-type embryos (Figure 7). Because γ-tubulin::GFP is under the control of pie-1 regulatory sequences, we cannot rule out the possibility that endogenous γ-tubulin is overexpressed in let-711 mutants. Nonetheless, together these results indicate that LET-711 can differentially affect the expression and/or localization of centrosome-associated proteins. Further, the increased accumulation of ZYG-9 without a concomitant increase in AIR-1 in the let-711 embryos provides an explanation for the mutual suppression of spindle positioning defects observed in let-711;zyg-9(RNAi) embryos.

LET-711 Is an Ortholog of NOT1, the Core Component of the CCR4/NOT Complex

To begin to address how LET-711 affects centrosomes and microtubules at the molecular level, we cloned the let-711 gene. Classical recombination mapping placed let-711 on Chromosome III between sma-3 and cyk-1. Transformation experiments using pools of cosmids spanning the region between sma-3 and cyk-1 failed to give any rescue of let-711(s2587) lethality (unpublished data). Therefore, to further define the position of let-711, SNP mapping (Wicks et al., 2001) was carried out, which suggested that let-711 is between SNP-T07E3[1] and SNP-pkP3076, very close to SNP-F57B9[1]. DNA from let-711(s2587) homozygous larvae was used to PCR-amplify and sequence 12 predicted genes spanning the region between SNP-T07E3[1] and SNP-pkP3076. A protein altering mutation was found only in the F57B9.2 gene. Sequencing of DNA from it150 and the two let-711 early larval lethal alleles revealed changes in F57B9.2 as well (see below and Materials and Methods for details).

To gain additional evidence that F57B9.2 corresponds to let-711, we performed RNAi. RNAi of this gene has been reported to produce multiple defects, including larval arrest, sterility, embryonic lethality, and osmotically sensitive eggs (Gonczy et al., 2000; Maeda et al., 2001; Kamath et al., 2003; Simmer et al., 2003; Sonnichsen et al., 2005), consistent with the phenotypes we have observed for let-711 (Table 1), but no defects in spindle positioning were noted. When bacteria expressing F57B9.2 (Kamath et al., 2003) were fed to wild-type L4 stage worms, worms produced viable progeny during the first 24 h of exposure and then quickly ceased egg production after producing a few osmotically sensitive embryos that appeared multinucleate or failed to progress. To produce a weaker loss of let-711 function, bacteria expressing the F57B9.2 RNA were mixed 1:1 with control bacteria. Although treated worms eventually became sterile, they produced dead embryos from ∼18 to 30 h after exposure, and embryos examined at 24–26 h showed a failure of nuclear rotation or the spindle skewed toward the posterior or lateral cortex during anaphase (9/30 embryos); embryos examined after this time point were osmotically sensitive and arrested. This spindle positioning phenotype is very similar to that seen in embryos produced by let-711(s2587/it150) worms and it150 homozygous worms (Table 1, footnote). Together with the sequence data, these results indicate that let-711 corresponds to F57B9.2.

The F57B9.2 gene is predicted to encode a protein of 2500 amino acids. BLAST searches (Altschul et al., 1997; Tatusova and Madden, 1999; Schaffer et al., 2001) of the predicted protein reveal a high degree of similarity to the NOT1 protein, conserved in yeast, flies, and vertebrates including humans (Collart and Timmers, 2004); this gene is referred to as ntl-1 (NOT-like-1) in the C. elegans database (http://www.wormbase.org/). The N-terminal 500 amino acids of C. elegans NOT1/LET-711 shows only 10% amino acid identity to human NOT1, but the remaining protein shows 36% identity throughout its length, with small regions of greater than 50% identity. Drosophila NOT1 and Saccharomyces cerevisiae NOT1 are 33 and 22% identical, respectively, with amino acids 500-2500 of C. elegans NOT1/LET-711. Based on a variety of studies, the NOT1 protein is a scaffolding component of a large multisubunit complex called CCR4/NOT, which has been implicated in both positive and negative control of transcription, repression of gene expression through mRNA deadenylation, and degradation of proteins via ubiquitination (Collart and Timmers, 2004).

The three larval lethal alleles of let-711 each result in a premature stop codon that is predicted to truncate the protein: The s2587 allele changes amino acid Q1053 to a stop, and s2473 and s2790 change Q1878 and Q2362 respectively to stops. The larval alleles likely represent the complete loss of zygotic function for this protein. In contrast, the maternal allele it150 results in an altered 3′ splice acceptor site in intron 15 (see Materials and Methods for nucleotide changes). The it150 mutant phenotype is much weaker than that of either the s2473 and s2790 mutations, which encode stop codons in later exons; thus, the mutated it150 splice site may result in an alternatively spliced form of the protein rather than a frameshift that results in a premature stop. Given the identity of LET-711 as a member of the CCR4/NOT complex and the observed effects on the accumulation of ZYG-9, LET-711 likely acts through regulating the expression of ZYG-9 and other centrosome-associated proteins.

DISCUSSION

In the C. elegans embryo, proper positioning of the mitotic spindle during cell division requires astral microtubules that are thought to interact with motors at the cell cortex. Disruption or alterations in these interactions, in particular mutations or conditions that result in shorter microtubules, affect the ability of the nuclear–centrosome complex to move to the center and orient properly on the anterior/posterior axis of the embryo (Hyman and White, 1987; Matthews et al., 1998; Gonczy et al., 2001; Bellanger and Gonczy, 2003; Le Bot et al., 2003; Srayko et al., 2003; Wright and Hunter, 2003; Phillips et al., 2004). Here we show that let-711 is required for centration and rotation of the nuclear–centrosome complex in the 1-cell C. elegans embryo. Interestingly however, instead of short microtubules, let-711 embryos had more long microtubules than wild-type embryos during the time of centration and rotation. The microtubules were more stable to cold treatment as well, which could indicate they have altered dynamics under physiological conditions. This let-711 phenotype is fairly novel among mutations affecting spindle structure or phenotype in C. elegans, the only other report of more stable microtubules being for gain-of-function mutations in tubulin (Wright and Hunter, 2003). The changes in microtubule length and stability observed in let-711 embryos could affect spindle positioning in several ways. If centration and rotation require depolymerization of microtubules to pull the centrosome toward the cortex, the increased stability of the microtubules in let-711 embryos could result in static nonproductive attachments to cortically anchored motors or the failure to undergo search and capture to interact with motors. Alternatively, the length and or stability of the microtubules observed in let-711 embryos could sterically interfere with the ability of the nuclear–centrosome complex to move through the cytoplasm. Recently, it has been proposed that centration (but not necessarily rotation) is due to length-dependent pulling forces on microtubules that extend anteriorly in the cytoplasm (Kimura and Onami, 2005). Although longer than normal microtubules should not disrupt central cytoplasm pulling forces based on this model, long microtubules making improper cortical interactions could nonetheless interfere with movement. Regardless, the let-711 phenotype, along with the observation that zyg-8 embryos had variable defects in rotation without a detectable change in microtubule length (Gonczy et al., 2001), highlight the need for a tight control of microtubule dynamics and length during spindle orientation. Such dynamics are a potential target of regulation by PAR polarity cues and G protein signaling, and indeed measurement of microtubule residency time at the cortex revealed differences in microtubule dynamics in the anterior and posterior PAR domains (Labbe et al., 2004).

The phenotype of let-711 mutant embryos suggests that wild-type LET-711 may affect some aspect of microtubule dynamics, and our analysis of ZYG-9 accumulation and the molecular identity of LET-711 suggest this effect is through the regulation of the amounts of microtubule-associated proteins. LET-711 is an ortholog of the NOT1 protein, which is the core component of the CCR4/NOT complex. Studies in several organisms have implicated the NOT complex in transcriptional activation and repression, mRNA deadenylation, and ubiquitination (reviewed in Collart and Timmers, 2004). Multiple proteins that function in this complex have been identified, and subgroups are involved in different aspects of regulation. For example, DHH1 (a dead box helicase) interacts with NOT1 through CCR4 (the catalytic subunit of mRNA deadenylase) to form the major mRNA deadenylase activity in S. cerevisiae, whereas NOT2, 3, and 5 have been shown to act in transcriptional repression but not mRNA deadenylation (Albert et al., 2000; Badarinarayana et al., 2000; Chen et al., 2002; Tucker et al., 2002; Collart and Timmers, 2004). NOT4 may act separately from both of these groups, as it shows homology with E3 ubiquitin ligases and has a mutant phenotype distinguishable from that of the other components (Albert et al., 2000; Collart and Timmers, 2004). The observation that ZYG-9 centrosomal levels are increased in let-711 embryos compared with wild type is consistent with a role for LET-711 in negatively regulating the expression of this protein. Because an effect on ZYG-9 was only observed for centrosomal accumulation, it appears that either LET-711 regulates ZYG-9 post-translationally, for example, through ubiquitination, or indirectly through another protein. The view that ZYG-9 levels are not regulated through the deadenylation subcomplex of CCR4/NOT1 is consistent with recent studies of CGH-1, the closest C. elegans homolog of yeast DHH1. No defects in spindle positioning were observed after partial RNAi depletion of CGH-1, although a profound defect in the formation of interzonal microtubules in anaphase spindles was observed (Audhya et al., 2005). Stronger loss of cgh-1 activity results in larval arrest or sterility, and similar phenotypes have been reported for RNAi depletion of other members of the CCR4/NOT complex (Navarro et al., 2001; Boag et al., 2005; Molin and Puisieux, 2005; Sonnichsen et al., 2005). A more detailed examination of embryonic division after varying degrees of RNAi will be needed to determine which activities of the CCR4/NOT complex are involved in regulating ZYG-9 and spindle positioning.

Given it role in regulating multiple levels of gene expression, the reduction of LET-711/NOT-1 is predicted to affect many different processes. The pleiotropic nature of the let-711 phenotype—larval arrest, sterility, and arrested 1-cell embryos under strong loss of function conditions—is consistent with the loss of regulation of multiple proteins. However, it is interesting that fairly specific spindle positioning defects occur under partial loss-of-function conditions. Both the it150 and it150/s2587 backgrounds, as well as RNAi treatment, gave spindle-positioning phenotypes without obvious defects in meiosis, pronuclear migration, or overall polarity, which are easily scored using DIC microscopy. Thus, either NOT1/LET-711 regulates a small number of targets at this stage of development, or spindle positioning is highly sensitive to changes in protein levels, perhaps especially increases. A more extensive study of protein expression in let-711 will be required to distinguish between these two possibilities. However, we note that sensitivity to the levels of ZYG-9 is consistent with previous studies on microtubule dynamics in C. elegans. In many systems, microtubule dynamics is regulated by a balance between proteins that stabilize microtubules, allowing them to grow, and proteins that promote depolymerization (Tournebize et al., 2000; Kinoshita et al., 2001; Holmfeldt et al., 2004; Wordeman, 2005). ZYG-9, the C. elegans homolog of XMAP215, and its partner TAC-1 are required for long astral microtubules in embryos (Matthews et al., 1998; Bellanger and Gonczy, 2003; Le Bot et al., 2003; Srayko et al., 2003) and for the rapid polymerization rate of microtubules observed in wild-type embryos (Srayko et al., 2005). Interestingly however, CeMCAK (klp-7), the sole ortholog of the major depolymerization factor described in other systems, appears to affect nucleation rate but not microtubule polymerization rate, and ZYG-9/TAC-1 was found to be the most prominent regulator of microtubule dynamics in an RNAi study of several microtubule-associated proteins (Srayko et al., 2005). Thus, C. elegans embryos may be even more sensitive to small changes in the levels of ZYG-9 than in other systems. With this view, the increased levels of ZYG-9 in the let-711 would be responsible at least in part for the changes in microtubule length observed. The mutual suppression we observed in let-711;zyg-9 embryos is consistent with this model. At the same time, the analysis of cold stability and microtubule regrowth after depolymerization showed that not all aspects of microtubule behavior are opposite in the two single mutants. These observations suggest that LET-711 affects other centrosome or microtubule-associated proteins in addition to ZYG-9.

Although the targets of LET-711/NOT1 remain to be determined, the results presented are consistent with the model that not all centrosome-associated proteins are overexpressed and/or accumulate to higher levels at the centrosome. A hierarchy of proteins that are recruited to centrosomes during maturation has been described. AIR-1 and γ-tubulin are recruited rather late in the sequence, and both of these are required for wild-type levels of ZYG-9 (Hannak et al., 2001, 2002). Because we did not detect higher levels of AIR-1 at the centrosome in let-711 embryos, it thus seems likely that the other antigens that precede it in the hierarchy are not increased at the centrosome. It is still possible that endogenous γ-tubulin is recruited to higher levels in let-711 embryos. We may not have detected a change in γ-tubulin in this study, either because the GFP-tagged protein acts differently than endogenous γ-tubulin or because let-711 does not affect expression of pie-1, the gene whose regulatory sequences were used to express γ-tubulin::GFP. Even if endogenous γ-tubulin does accumulate to higher levels in let-711 embryos, which then recruits ZYG-9, this phenotype would still appear to be independent of normal centrosome maturation for the reasons cited above. Thus, the centrosome expansion phenotype reported for let-711 does not appear to be due to premature centrosome maturation.

An alternative interpretation of the let-711 expanded centrosome phenotype is that the increased accumulation of ZYG-9 or some other centrosome protein changes centrosome morphology. Centrosome size varies widely in different cell types, and studies in other systems have shown that some centrosome-localized proteins show both microtubule-independent (maturation-dependent) and microtubule-dependent association. For example, γ-tubulin has a broader distribution at spindle poles during mitosis than during interphase in many cases, which is partly dependent on intact microtubules and the severing of microtubules by katanin (Buster et al., 2002). Similarly, the area occupied by katanin and tubulin varies with cell type (McNally and Thomas, 1998; Buster et al., 2002). A third interpretation of the large centrosome phenotype in let-711 embryos is that the longer microtubules result in increased forces that expand the centrosome prematurely, compared with the normal expansion of the centrosome during late anaphase and telophase in wild-type embryos, which is thought to reflect higher forces at this time (Severson and Bowerman, 2003). However, we note that the area of α -tubulin staining after cold treatment, when microtubules would no longer contact the cortex, was consistently larger in let-711 embryos than in wild-type controls (Figure 3 and unpublished data). Thus, we favor the view that at least some aspect of centrosome expansion in let-711 embryos is due to changes at the centrosome itself.

In summary, we have identified a role for the conserved NOT1 protein in regulating the expression levels of a microtubule-associated protein during cell division in the early C. elegans embryo. The analysis of CGH-1, a potential component of the CCR4/NOT1 complex in C. elegans, also implicates this complex in regulating microtubule-binding proteins during mitosis (Audhya et al., 2005). Roles for the CCR4/NOT complex in mitosis and/or the cell cycle are conserved in other organisms. Mutations in yeast NOT1 were identified in screens for cell cycle mutants, and subsequent studies have revealed a link between mitotic exit and transcriptional regulation by CCR4/NOT1 (Morel et al., 2003; Collart and Timmers, 2004). Similarly, the Drosophila homolog of CCR4 is required for the regulation of genes essential for normal cyst divisions in the ovary (Morris et al., 2005). Roles for CCR4/NOT in regulating the expression of maternally provided mRNAs and proteins may also be conserved. In Drosophila, CCR4/NOT complex members play roles in mRNA deadenylation and degradation, which aid in localizing mRNAs to specific regions to pattern the oocyte and embryo (Benoit et al., 2005; Semotok et al., 2005). Our findings indicate that the NOT1 complex regulates maternally provided mRNAs or proteins in C. elegans as well. In the case of ZYG-9, which is essential for both oocyte meiosis and embryonic mitosis (Kemphues et al., 1986; Mains et al., 1990; Matthews et al., 1998), LET-711/NOT1 may play a role in either spatial localization to the centrosome, or in fine-tuning the absolute level of protein needed for different functions during the oocyte to embryo transition or during mitotic cell cycle progression. The identification of additional targets of NOT1/LET-711 activity and how they are regulated will lead to a better understanding of the precise role of LET-711 in microtubule and centrosome function and other early developmental processes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ken Kemphues for strains and antibodies as well as his support during the initial phases of this work, and we are indebted to Frank McNally for the zyg-9 RNAi construct, help with quantification of microtubules, and insightful comments on the project and the manuscript. We also thank Eric Mortensen for help with SNP mapping; Dave Baillie, Bruce Bowerman, Jill Schumacher, Iain Cheeseman, and Arshad Desai for strains and antibodies; and Dan Starr and Lori Krueger for critical comments on the manuscript. Additional strains were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (funded by the National Institutes of Health [NIH] National Center for Research Resources), and the P granule OICID4 antibody was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, maintained by The University of Iowa, Department of Biological Sciences, Iowa City, IA 52242). This research was supported by fellowships from the UC Davis Office of Graduate Studies and the NIH Molecular and Cellular Biology Training Grant to L.D.-B., as well grants from the NIH (GM56284 and GM68744), American Cancer Society (RPG-00-076-01-DDC), and University of California Cancer Research Coordinating Committee to L.R.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E06-02-0107) on September 13, 2006.

REFERENCES

- Albert T. K., Lemaire M., van Berkum N. L., Gentz R., Collart M. A., Timmers H. T. Isolation and characterization of human orthologs of yeast CCR4-NOT complex subunits. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:809–817. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.3.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schaffer A. A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D. J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audhya A., Hyndman F., McLeod I. X., Maddox A. S., Yates J. R., 3rd, Desai A., Oegema K. A complex containing the Sm protein CAR-1 and the RNA helicase CGH-1 is required for embryonic cytokinesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell Biol. 2005;171:267–279. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badarinarayana V., Chiang Y. C., Denis C. L. Functional interaction of CCR4-NOT proteins with TATAA-binding protein (TBP) and its associated factors in yeast. Genetics. 2000;155:1045–1054. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.3.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellaiche Y., Gotta M. Heterotrimeric G proteins and regulation of size asymmetry during cell division. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005;17:658–663. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]