Abstract

Although sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) has been considered a potent regulator of skeletal muscle biology, acting as a physiological anti-mitogenic and prodifferentiating agent, its downstream effectors are poorly known. In the present study, we provide experimental evidence for a novel mechanism by which S1P regulates skeletal muscle differentiation through the regulation of gap junctional protein connexin (Cx) 43. Indeed, the treatment with S1P greatly enhanced Cx43 expression and gap junctional intercellular communication during the early phases of myoblast differentiation, whereas the down-regulation of Cx43 by transfection with short interfering RNA blocked myogenesis elicited by S1P. Moreover, calcium and p38 MAPK-dependent pathways were required for S1P-induced increase in Cx43 expression. Interestingly, enforced expression of mutated Cx43Δ130–136 reduced gap junction communication and totally inhibited S1P-induced expression of the myogenic markers, myogenin, myosin heavy chain, caveolin-3, and myotube formation. Notably, in S1P-stimulated myoblasts, endogenous or wild-type Cx43 protein, but not the mutated form, coimmunoprecipitated and colocalized with F-actin and cortactin in a p38 MAPK-dependent manner. These data, together with the known role of actin remodeling in cell differentiation, strongly support the important contribution of gap junctional communication, Cx43 expression and Cx43/cytoskeleton interaction in skeletal myogenesis elicited by S1P.

INTRODUCTION

Skeletal muscle formation during development requires several cellular and molecular events that lead to the maturation of myoblasts into multinucleated myofibers. The onset of the terminal differentiation process is characterized by cell cycle withdrawal and myogenin synthesis followed by the expression of muscle-specific genes including sarcomeric proteins and creatine kinase (CK; Lassar et al., 1989). Adult skeletal muscle have the ability to regenerate after injury from quiescent mononucleated satellite cells which, lying between the sarcolemma and the basal lamina, use the same differentiation program as developing myoblasts (Hawke and Garry, 2001; Grounds et al., 2002). Although much remains to be learned on the inductive factors and molecular mechanisms involved in the myogenesis, it is well established that diverse intercellular signaling pathways may influence the regulation of myoblast differentiation during development and regeneration of skeletal muscle. One of them is mediated by gap junctions, specialized membrane regions composed of aggregate of intercellular channels connecting directly the adjacent cells (Simon and Goodenough, 1998). Each intercellular channel is formed by the conjunction of two hemichannels composed of six protein subunits belonging to the connexin family, whose connexin (Cx) 43 is the most widely expressed member (Sàez et al., 2003). Although absent in adult skeletal muscle fibers, Cx43 is present in the early stages of myogenesis, and Cx43-containing gap junctions are required for determining the correct cellular specification during myogenesis (Araya et al., 2003). Indeed, Cx43 is transiently expressed in myoblasts being down-regulated before their fusion into multinucleated myotubes (Gorbe et al., 2005). Moreover, the application of connexin channel blockers (Proulx et al., 1997a) as well as the inducible deletion of Cx43 protein (Araya et al., 2005) have been shown to dramatically affect myogenic differentiation, whereas the overexpression of Cx43 by rhabdomyosarcoma cells has been described as enhancing the differentiation capacity (Proulx et al., 1997b). In general, the effects of Cx43 expression have been attributed to the role of gap junctions in the establishment of organized pathways for the intercellular transfer of small metabolites and messenger molecules necessary for the coordination and guide of the interacting myoblasts to their final differentiation (Goldberg et al., 1999). However, evidence is accumulating that connexins may have additional functions independent of their gap channel–forming ability (Giepmans, 2004; Stout et al., 2004; Jiang and Gu, 2005). Indeed, several lines of evidences have shown that Cx43 regulates cell growth and migration by mechanisms that do not require intercellular communication in normal and transformed neuronal and epithelial cells (Huang et al., 1998a, 1998b; Omori and Yamasaki, 1998; Moorby and Patel, 2001; Qin et al., 2002). Moreover, the exogenous expression of mutant nonfunctional connexins has been reported to protect glial cells against injury and apoptotic cell death (Lin et al., 1998). So far, no evidence of the existence of a direct action of the Cx43 protein on the regulation of cell differentiation and skeletal muscle formation has been reported.

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) is a bioactive lipid that participates in the regulation of numerous cell processes, such as cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, and apoptosis, and acts as intracellular mediator and ligand for specific S1P receptors (Saba, 2004). We have recently shown that S1P is a potent inducer of skeletal muscle differentiation (Donati et al., 2005), and its specific Edg5/S1P2 receptor is down-regulated during myogenesis (Meacci et al., 2003). Notably, we have also demonstrated that the activity and protein content of sphingosine kinase, the enzyme catalyzing the formation of S1P, is greatly enhanced in differentiating C2C12 myoblasts, and its silencing delays myoblast maturation, thus implicating a physiological role of S1P in myogenesis (Meacci, E., Nuti, F., Donati C., Cencetti, F., Farnararo, M., and Bruni, P., unpublished results).

On the basis of the above reported observations, in the present study we investigated whether the regulation and assembly of Cx43 into gap junctions could represent a critical event in C2C12 myoblast differentiation elicited by S1P and whether Cx43 protein per se could contribute to this process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Cultures

Murine C2C12 myoblasts (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were routinely grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS, Sigma). For proliferation experiments, cells were seeded in 96-well plates and utilized when ∼50% confluent. For myogenic differentiation experiments, cells were grown in 100-mm dishes or six-well plates until 95% confluent and induced to differentiate by switching to differentiation medium (DM), DMEM containing 2% horse serum (HS, Sigma) for different times (24, 48, and 72 h and 5 d) in the presence or absence of S1P (1 μM, 2 mM stock solution in dimethylsulfoxide, Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA).

Cell Treatments

C2C12 cells were challenged with 5 μM of the specific p38 MAPK inhibitor SB239063 (Tocris Cookson, Bristol, United Kingdom) and 10 μM of the ERK1/ERK2 pathway inhibitor PD98059 (Calbiochem) prepared in 0.05% DMSO, 30 min before agonist addition. The specific effect of the various inhibitors was tested by Western blot analysis evaluating the phosphorylation status of p38 MAPK and ERK1/2. To investigate calcium-dependent events, C2C12 cells were incubated in the dark for 1 h before S1P challenge with 15 μM of the Ca2+ chelator 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid/acetoxymethyl ester (BAPTA/AM, Calbiochem) prepared in 100 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.0, and 0.1% Pluronic F-127 as previously described (Meacci et al., 2002b). The BAPTA/AM efficacy was tested by Western blot analysis examining the inhibition of S1P-induced PKCα translocation to the membrane fraction that, in C2C12 cells, occurs via a Ca2+-dependent mechanism (Meacci et al., personal communication).

Silencing of Cx43 by siRNA

To silence the expression of Cx43, short interfering RNA duplexes (siRNA) were used (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) corresponding to three distinct regions of the DNA sequence of mouse Cx43 gene (NM_010288): 5′CCCAACUGAACCUUAAGAA3′, 5′CCUCACCAAAUGA UUUCUA3′, and 5′CCUACCAGUUUCUUCAAGU3′. The sequences were evaluated against the database using the NIH Blast program to test for specificity. A nonspecific scrambled (SCR) siRNA was used as control. C2C12 cells grown into 60-mm dishes in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS were transfected with the mixed combination of the above reported three RNA duplexes, using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (1 mg/ml; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, Lipofectamine 2000 was incubated with Cx43-siRNA (ratio 2:1) at room temperature for 20 min, and successively the lipid/RNA complexes were added with gentle agitation to C2C12 cells. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were shifted to DM in the presence or absence of S1P for a further 48 h and used for the experiments. Longer incubation times had deleterious effects on C2C12 cell viability and survival, as evaluated by visual inspection and MTS-dye reduction assay (Promega, Madison, WI). To evaluate the specific knock-down of Cx43, cell lysates from myoblasts transfected with Cx43- or SCR-siRNA were immunoblotted, and protein was detected using specific anti-Cx43 antibodies.

Construction of GFP-wtCx43 and Mutated GFP-Cx43Δ130–136 Expression Vectors

Cx43 cDNA was obtained by reverse transcription of 1 μg of total RNA extracted from C2C12 myoblasts using TRIREAGENT (Sigma), according to the manufacturer's protocol and amplified using SuperScriptOne-Step RT-PCR System (Invitrogen) and the following mouse gene-specific primers designed in the coding region: forward primer 1: 5′ATGGGTGACTGGAGCAGCG CCTTG3′ and reverse primer 1: 5′GGCAGCTTGAT GTTCAAGCCTG3′and). A cDNA fragment corresponding to mouse Cx43 with a deletion of amino acids 130–136 (Krutovskikh et al., 1998; Upham et al., 2003) was obtained by the amplification of two overlapped fragments: fragment A amplified using forward primer 1 and the reverse primer 2 (5′TTCAATCCCAAT CTGTTCAGGTGCAT3′) and fragment B amplified using forward primer 2 (5′AAGCAGATTGGGATTGAAGAACACGGC3′) and reverse primer 1. Cx43 (wtCx43) or Cx43Δ130–136 (DNCx43) cDNAs were subcloned into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1/NT-GFP-TOPO using the TA cloning kit and following the manufacturer's supplied protocol (Invitrogen). The nucleotide sequences of all PCR products were confirmed by automated DNA sequencing.

Stable Cell Transfections

To obtain cells stably overexpressing GFP-wtCx43 or GFP-DNCx43, myoblasts were plated onto 60-mm dishes and transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (1 mg/ml) mixed with pGFP-wtCx43, pGFP-DNCx43, or plasmid alone. After 36 h, the cells were replated in the presence of G418 (300 μg/ml; Invitrogen) and expanded under selective conditions. Selected bulk population was used to avoid potential phenotypic changes due to selection and propagation of clones from single individual cells. Ectopic Cx43 expression levels were routinely monitored by Western blot analysis using specific anti-Cx43 or anti-GFP antibodies (Santa Cruz). Empty vector-transfected cells were utilized as control. Because previous studies have shown that enforced expression of connexins can affect cell survival, MTS-dye reduction assay (Promega) in vector control and GFP-wtCx43– or GFP-DNCx43–transfected cells was performed. The capability of reducing MTS dye after 24 h of serum deprivation evaluated in GFP-wtCx43– or GFP-DNCx43–expressing myoblasts was not significantly different from that in control cells transfected with empty vector alone (0.76, 0.81, and 0.79 arbitrary units, respectively; data are media ± SEM; n = 3 for independent experiments performed in quadruplicate, with SEM always <15%).

Reverse Transcription and cDNA Amplification

Total RNA (1 μg), isolated using TRIREAGENT (Sigma) from cells incubated in the presence or the absence of S1P for 24, 48, and 72 h was added to 4 μl of 2.5 mM dNTP and 1 μl of 0.5 mg/ml random primers. Reverse transcription was performed at 42°C for 60 min using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) as described in the manufacturer's protocols. Different amount of reverse transcription reaction were used for semiquantitative PCR in the presence of mouse Cx43 gene-specific primers designed in the coding region: forward primer 1 (5′ATGGGTGACTGGAGC AGCGCCTTG3′) and the reverse primer 2 (5′TTCAATCCCAATC TGTTCAGGTGCAT3′). Amplified DNA was separated by electrophoresis onto 1.8% agarose gel, and exact size was evaluated by comparison with PCR 100-base pair Low Ladder (Sigma). β-actin, was amplified using specific primers (forward: 5′ TCATGTTTGAGACCTTCAACACCC3′; reverse: 5′GATGGAATTGAA TGTAGTTTC3′; Invitrogen) and used as an internal reference control to normalize relative levels of gene expression.

Lysate Preparation and Western Blot Analysis

Native, silenced, and stable overexpressing C2C12 myoblasts were incubated in the presence or the absence of S1P and/or inhibitors, washed twice in cold PBS, scraped, and lysed for 30 min at 4°C in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 6 mM EGTA, 15 mM Na4P2O7, 20 mM NaF, 1% Nonidet, and protease inhibitor cocktail (1.04 mM AEBSF, 0.08 μM aprotinin, 0.02 mM leupeptin, 0.04 mM bestatin, 15 μM pepstatin A, and 14 μM E-64, Sigma) essentially as previously described (Kaliman et al., 1999). Lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and protein concentration was measured using the Bradford microassay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). For Western blot analysis, proteins from cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE. To immunodetect endogenous Cx43, specific monoclonal anti-Cx43 antibodies (1:1000, Chemicon, Temecula, CA) directed against a synthetic peptide corresponding to position 252–270 of the mouse sequence or polyclonal antibodies directed against C-terminal region of the protein (C6219, Sigma) were used. Rabbit polyclonal anti-Cx39 antibodies (kindly provided by Drs. Willecke and von Maltzahn, Institut fur Genetik, Abteilung Molekulargenetik, Universitat Bonn, Germany) direct against the C-terminal region of rat protein were also used (von Maltzahn et al., 2004). Overexpression of recombinant GFP-wtCx43 or GFP-DNCx43 protein were tested using monoclonal anti-Cx43 or anti-GFP (1:1000; Santa Cruz). For myogenic differentiation experiments, polyclonal anti-myogenin (clone F5D, Sigma), monoclonal anti-skeletal fast myosin heavy chain (MHC; clone MY-32, Sigma), monoclonal anti-caveolin-3 (cav-3; Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), and monoclonal anti-β-actin (Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO) were used. Bound antibodies were detected by anti-rabbit and anti-goat immunoglobulin G1 conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Santa Cruz) and ECL reagents (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden).

Confocal Immunofluorescence

C2C12 cells grown on glass coverslips were incubated with S1P (1 μM) for the indicated times, fixed in 0.5% buffered paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, permeabilized with cold acetone for 3 min, blocked with PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) and 3% glycerol, and immunostained (1 h at room temperature) with primary antibodies: monoclonal anti-Cx43 (1:250, Chemicon) and polyclonal anti-cortactin (1:50, Santa Cruz). After washing, cells were further incubated (1 h at room temperature) with Alexa 488- or Cy5-conjugated IgG (1:100, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), rinsed, and mounted with an antifade mounting medium (Biomeda Gel mount, Electron Microscopy Sciences, Foster City, CA). Negative controls were carried out by replacing the primary antibody with nonimmune mouse serum. Counterstaining was performed with either tetramethyl rhodamine-isothiocyanate (TRITC)-labeled phalloidin (1:100; Sigma) to reveal F-actin or with propidium iodide (PI, 1:30; Molecular Probes) to reveal nuclei. Cells were then examined with a Bio-Rad MCR 1024 ES confocal laser scanning microscope (Bio-Rad) equipped with a Krypton/Argon laser (15 mW) for fluorescence measurements and with differential interference contrast optics. Fluorescence was collected by a Nikon PlanApo 60× oil immersion objective (Melville, NY). Series of optical sections (512 × 512 pixels) at intervals of 0.4 μm were taken and superimposed as a single composite image. The laser potency, photomultiplier, and pin-hole size were kept constant. The optical density of Cx43 immunoreactivity was also measured to quantify Cx43 expression in myoblasts during differentiation. In each experimental group, at least 30 different cells were analyzed, and the mean optical density (±SEM) was calculated.

Lucifer Yellow Dye Transfer Analyses

To reveal functional gap junctions, the gap junction-permeant dye Lucifer yellow (20% in PBS; Molecular Probes) was microinjected into single cells under a phase-contrast microscope using a pressure injection system (Femtojet InjectMan NI2, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) as previously described (Formigli et al., 2005a). The fluorescent coupling was viewed under a Nikon Diaphot 300 microscope equipped with fluorescence illumination and FITC filters (excitation 488 nm, emission 512 nm) and photographed using a Nikon digital camera (1 image per second). The specificity of dye transfer was tested by pretreatment with heptanol (1 mM, Sigma), a blocker of gap junction coupling. The extent of gap junction intercellular communication was quantified by counting the number of fluorescent cells surrounding each injected cell (number of dye-coupled cells/microinjection). At least 20 independent microinjections were performed for each sample (n = 3).

Electrophysiological Measurements

Electrophysiological properties of both gap junctions and hemichannels were investigated. Experiments aimed to study gap junction channels were achieved in C2C12 cell pairs by dual whole cell patch-clamp, as previously described (Formigli et al., 2005a, 2005b). C2C12 myoblasts were used after 24 h of culture in DM in the presence or absence of S1P. Initially, the membrane potentials of cell 1 (V1) and 2 (V2) were clamped to the same value, V1 = V2. V1 was then changed to establish a transjunctional voltage Vj = V2 − V1. Cell 1 was stepped using a bipolar pulse protocol. The pulses were 4.7 s long. Currents recorded from cell 1 represented the sum of two components: the transjunctional current (Ij) and the membrane current of cell 1. Currents recorded from cell 2 corresponded to −Ij. The electrophysiological properties of connexin hemichannel, IhCh current, and GhCh conductance, and the IhCh-V relationship were studied in single cells using a single pulse protocol from −70 to 70 mV in 10-mV increments. The pulses were 4.7 s long. Holding potential was −60 mV. The amplitudes of IhCh were determined at the beginning (IhCh,inst) and at the end of each pulse (IhCh,ss) to estimate the conductances GhCh,inst and GhCh,ss. The normalized GhCh,ss values were calculated from the ratios IhCh,ss/V, normalized to the maximal IhCh,ss at 70 mV, averaged, and plotted versus V. The normalized GhCh,ss-V plots were fitted by the Boltzmann equation: GhCh,ss = (GhCh,max − GhCh,min)/(1 + e(A(V − V0)) + GhCh,min, where GhCh,max and GhCh,min are the maximal and minimal conductance at large positive and negative Vm, respectively. V0 corresponds to V at which GhCh,ss is half-maximally activated. In some experiments, we used the Tyrode' solution or a bath solution as that previously reported by (Valiunas, 2002). In the presence of both solutions we observed an outward K+ current that appeared at positive potentials. This indicated that some voltage-dependent K+ channels were not activated by an holding potential of 0 mV (Kondo et al., 2000). Therefore, to block K+ channels and to improve the open state of hemichannels (Valiunas, 2002), a bath solution containing TEA and low Ca2+ concentration: 122.5 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 20 TEA-OH, and 10 mM HEPES were used.

Creatine Kinase Assay

After 72 h of culture, cells were washed with PBS and homogenized in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer, containing 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.2. The 20,000 × g supernatant was used to measure the activity of muscle creatine kinase (CK), as previously described (Naro et al., 1999). CK-specific activity was calculated and expressed as arbitrary units/mg.

Immunoprecipitation

Stable overexpressing myoblasts were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS to confluence and switched to DM. Native cells were incubated in growing medium and switched to DM in the presence or absence of 5 ìM SB239063, 30 min before S1P stimulation. After 24 h both cell preparations were washed in PBS and harvested on ice in 200 μl of precipitation assay lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 500 μM Na3VO4, 0.5% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitors (Sigma), and 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, pH 7.2) as previously described (Singh et al., 2005). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min, and the cell supernatant was used. For immunoprecipitations, polyclonal anti-Cx43 antibodies were incubated with cell lysates for 3 h followed by immunoprecipitation with protein A-Sepharose beads for 1 h. The beads were washed extensively in PBS, and bound proteins were eluted in Laemmli sample buffer followed by separation on SDS-PAGE and immunodetected using anti-cortactin and anti-actin antibodies (Cytoskeleton) or anti-Cx43 as described in Western Blot Analysis above.

Presentation of Data and Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by Student's t test, with a value of p < 0.05 considered significant. In RT-PCR and immunoblot experiments, densitometric analysis of the band intensities was performed using Imaging and Analysis Software by Bio-Rad (Quantity-One), determined by calculating the Cx43/β-actin ratios as percentage of control (set at 100), and reported as means ± SEM. Densitometric analysis of the intensity of the immunostaining for Cx43 was carried out on digitized images using NIH ImageJ software (NIH). In electrophysiological experiments, statistical analysis of differences between the experimental groups was performed by one-way ANOVA and Newman-Keuls post-test (p < 0.05 was considered significant). Calculations were made with Graph Pad Prism statistical program (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). pClamp9 (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA), SigmaPlot and SigmaStat (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA) were used for mathematical and statistical analysis of electrophysiological data.

RESULTS

S1P Induces Cx43 Protein Expression and Gap Junctional Communication in Differentiating Myoblasts

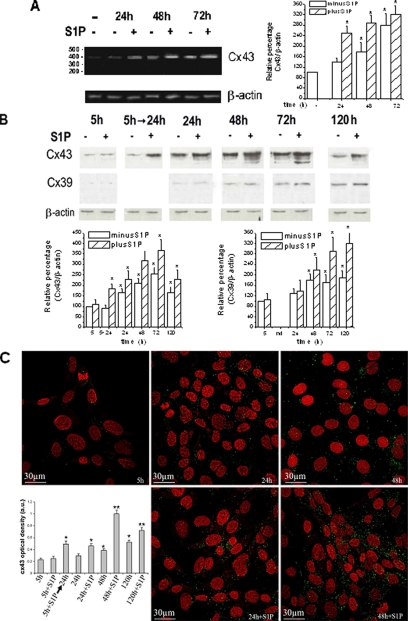

We first ought to determine whether Cx43 could be a possible target of S1P-induced C2C12 myoblast differentiation by RT-PCR and Western blot analysis in differentiating cells. As reported in Figure 1, A and B, Cx43 was greatly up-regulated at the mRNA and protein levels in differentiating cells and, particularly, in those treated with S1P, indicating that the bioactive lipid acted as a potent inducer of Cx43 expression in C2C12 myoblasts. In particular, the expression of the gap junction protein gradually increased from 24 up to 72 h and then declined with the progression of myogenesis, being barely detected in cells at 5 d of differentiation and in fully differentiated cells (unpublished data). Cx43 was found as a prevalent band of ∼43 kDa in control cells and as multiple bands of 40–46 kDa in S1P-treated myoblasts, suggesting that the bioactive lipid could also affect Cx43 posttranslation modifications. Parallel experiments were performed to verify whether S1P treatment affected the expression of other connexin such as Cx39, an isoform recently identified in differentiating myoblasts (von Maltzahn et al., 2004, 2006; Belluardo et al., 2005). As shown in Figure 1B, Cx39 was weakly detectable in C2C12 myoblasts, and its expression was not affected by S1P, at least in the early hours of differentiation (24–48 h). However, the expression level of Cx39 increased significantly in differentiating cells starting from 72 up to 120 h of incubation in DM, especially in the presence of S1P (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effects of S1P on Cx43 expression and protein localization in C2C12 myoblasts. (A) RT-PCR analysis. Total RNA (1 μg), prepared from C2C12 myoblasts incubated in DM at the indicated times in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 1 μM S1P, was used for reverse transcription and semiquantitative PCR analysis. An ethidium bromide–stained 1.8% agarose gel showing a band corresponding to Cx43 of the expected size (390 base pairs) is reported. Quantitative analysis of Cx43 mRNA expression is shown in the graphic as relative percentage (means ± SEM), obtained by calculating the Cx43/β-actin ratios of band intensities and normalizing to control (set as 100). The experiment was repeated three times with similar results. β-actin was used as an internal reference control. (B) Western analysis of Cx43 and Cx39 expression. Confluent C2C12 myoblasts were processed as indicated above. The content of Cx43 and Cx39 was analyzed in cell lysates by Western blot. Equally loaded protein (30 μg) was checked by expression of the nonmuscle-specific β isoform of actin. A blot representative of at least three independent experiments with similar results is shown. Band intensity was calculated as indicated in Materials and Methods, normalized and reported as relative percentage (means ± SEM) respect to control set as 100 (5 h in the absence of S1P). Quantitative analysis of Cx43 and Cx39 expression is shown in the graphic. (C) Confocal immunofluorescence of Cx43 expression. Confocal fluorescence micrographs of cells grown in DM in the presence or absence of 1 μM S1P at the indicated times, fixed, and stained with the primary antibodies for Cx43 to visualize the protein distribution (green) and with PI (red) to show nuclei. Cx43 is poorly expressed in control cells (5 h); its expression increases during differentiation and, in particular, after S1P stimulation. In S1P-treated cells the staining appears mainly localized in the perinuclear regions and at the appositional plasma membranes between adjacent myoblasts. Expression of Cx43 was quantified and plotted by SCION IMAGE. The images are representative of at least three separate experiments with similar results (*p < 0.01, **p < 0.005, n = 4).

Confocal immunofluorescence confirmed the temporal regulation of Cx43 protein expression detected by Western blot analysis (Figure 1C). Confluent C2C12 myoblasts expressed some Cx43 immunostaining, distributed as small green fluorescent dots both in the cytoplasm—in the perinuclear regions—and at the cell surface. However, after 24 and 48 h of S1P stimulation, the expression of Cx43 appeared remarkably increased compared with the levels detected in untreated cells. The immunofluorescent dots were abundantly found in the cytoplasm, likely within the protein synthesis pathway, as well as along regions of intimate cell-to-cell contacts, compatible with the formation of gap junction plaques. Of interest, the quantification of the fluorescent signal indicated that cells treated with S1P for 5 h and left in DM in the absence of the bioactive lipid for additional 20 h, showed higher levels of Cx43 than the untreated cells, consistent with an effect of S1P on the protein expression in the early hours of incubation (Figure 1C).

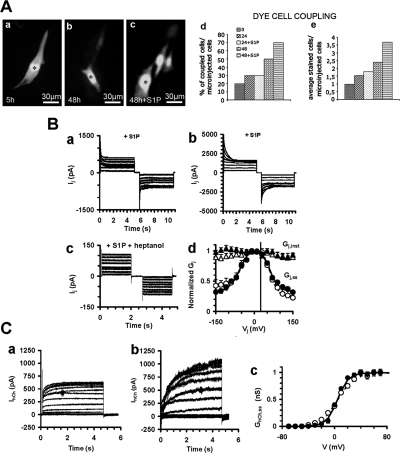

The increase of immunoreactive Cx43 at the appositional plasma membranes between adjacent myoblasts after S1P stimulation was consistent with the functional differences in the gap junction permeability, as detected by Lucifer yellow dye-transfer assay (Figure 2A). The efficacy of dye spreading in control was very low, with ∼20% of the cells showing dye coupling with only one neighboring cell. After 24 and 48 h of incubation in DM the extent of dye transfer slightly increased, with ∼30% of the cells showing 1–2 or 2–3 coupled cells, respectively. The long-term treatment with S1P significantly increased the extent of gap junction communication over that evaluated in controls, with ∼50 and 70% of the cells showing 1–2 and 3–4 coupled cells per injection, after 24 and 48 h of stimulation, respectively.

Figure 2.

Effect of S1P on gap-junctional intercellular communication. (A) Lucifer yellow dye/transfer analysis of gap junction communication. C2C12 cells were grown in DM in the presence or absence of 1 μM S1P at the indicated time and then microinjected with the gap junction–permeant dye. (a–c) Representative images of dye transfer from microinjected to neighboring cells in the reported experimental conditions. The cell into which the dye was microinjected is indicated with the asterisk. The images are representative of at least three independent experiments with similar results. (d and e) Quantitative analysis of dye cell coupling. The percentage of coupled cells versus the total amount of microinjected cells (d) and the average number of stained cells per microinjected cell (e) were reported. Note that S1P-treated cells exchange Lucifer yellow to an higher number of cells (3–4) compared with the untreated ones (1–2). (B) Transjunctional current (Ij) recordings. C2C12 cells were cultured in DM for 24 h in the presence or absence of 1 μM S1P and analyzed using dual patch-clamp. (a and b) Time course of intercellular currents (Ij) showing the ability of S1P to increase gap junction currents. (c) The treatment with heptanol blocks Ij in S1P-stimulated cells. (d) Normalized Gj,inst- and Gj,ss-Vj plots. Gj,inst is indicated as open triangles in unstimulated and filled triangles in S1P-stimulated cells. Gj,ss is reported as open circles and dashed line in unstimulated and as filled circles and continuous line in S1P-stimulated cells. Note that stimulation with S1P changes the current-voltage plot from asymmetric to symmetric one. The related Boltzmann parameters are reported in Table 1. (C) Hemichannel current (IhCh) recordings. C2C12 cells were processed as above, and IhCh was recorded by single patch-clamp. (a and b) IhCh time course; (c) normalized GhCh,ss-V plot for unstimulated (○ and – – –) and S1P-stimulated cells (● and —). The related Boltzmann parameters are reported in Table 1.

To further investigate the role of S1P on intercellular communication, we characterized the biophysical properties of gap junctional current by dual whole cell voltage-clamp. Figure 2B shows transjunctional current traces (Ij) in representative cell pairs in control condition and after 24 h of treatment. Interestingly, the amplitude of Ij and transjunctional conductance (Gj,ss) increased significantly at all the voltage values in cells treated with S1P. The dependence of this current and conductance on junctional channels was established by assessing its sensitivity to heptanol, a commonly used gap junction channel blocker. As expected, heptanol (1 mM) was able to inhibit both Ij and Gj,ss within 3–5 min (Figure 2B), since Gj,ss at + 10 mV ranged from 0.62 ± 0.04 (n = 8) to 0.72 ± 0.05 (n = 9) nS in control and stimulated cell pairs, respectively. Of interest, best-fit Boltzmann parameters showed that control cells had a slight asymmetrical voltage-dependent currents (Table 1). In keeping with our data that Cx39 was only weakly detectable in C2C12 myoblasts and in consideration that ambiguous data exist on the expression of Cx45 in these cells (Araya et al., 2005; von Maltzahn et al., 2006), we suggested that the asymmetric Bolzmann parameters were predominantly due to the inside-outside voltage dependence of Cx43 Gj previously described (White et al., 1994). However, the plot became symmetric after treatment with S1P and showed a slower inactivation compared with control, suggesting that S1P could affect the inside-outside voltage-dependence of Cx43-containing gap junctions, by reducing the fast gating, acting in the same manner as other chemicals (Bukauskas et al., 2001). Finally, we demonstrated that S1P affected the hemichannel conductance in myoblastic cells, because IhCh as well as its voltage sensitivity were significantly increased in S1P-treated cells compared with control, as indicated by the A parameter (Figure 2C, Table 1).

Table 1.

Boltzmann parameters for gap junctions and hemichannels in C2C12 cells

| Parameter | Gap junctions |

Hemichannels |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −S1P |

+S1P |

|||||

| Vj(+) | Vj(−) | Vj(+) | Vj(−) | −S1P | +S1P | |

| A (mV−1) | 0.065 ± 0.004 | 0.072 ± 0.003a | 0.064 ± 0.004 | 0.063 ± 0.004b | 0.08 ± 0.002 | 0.12 ± 0.002c |

| V0 (mV) | 62.10 ± 4.42 | −51.11 ± 4.32a | 62.03 ± 5.02 | −55.03 ± 5.02 | 5.0 ± 1.2 | 4.5 ± 0.9 |

| Gmin | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 0.45 ± 0.05a | 0.34 ± 0.04b | 0.32 ± 0.04b | ||

Data were obtained from C2C12 cells incubated in DM for 24 h in the absence (−) or presence (+) of S1P. The parameters were obtained by fitting normalized Gj,ss and GhCh,ss vs. voltage data (20–24 for each experimental condition).

Note that Boltzmann parameters at negative Vj, Vj(−), are significantly different with respect to those at positive Vj, Vj(+), in control but not in S1P-stimulated cells;

a p < 0.05 for Vj(−) vs. Vj(+);

b p < 0.05 for S1P-stimulated cell pairs vs. controls.

For hemichannel analysis, the value A representing the GhCh,ss voltage sensitivity is significantly increased in S1P-stimulated cells with respect to their control counterpart;

c p < 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Overall, all these data indicated that S1P promoted Cx43 protein expression and increased gap junctional and hemichannel permeability during the early phases of myogenesis.

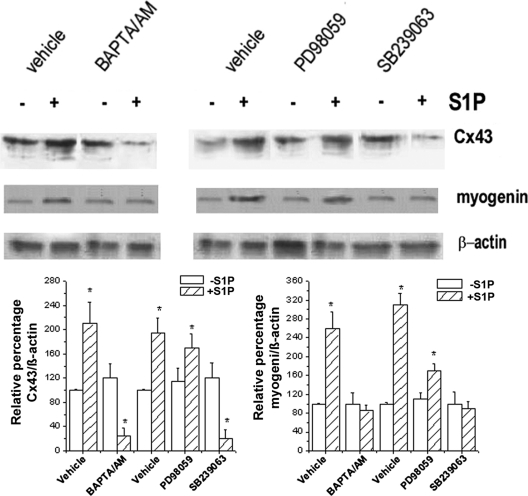

Calcium Increase and p38 MAPK Activity Are Involved in S1P-induced Cx43 Expression

Because gap junctions are required for normal myogenesis (Araya et al., 2005), we next investigated whether known mediators of the myogenic program and known targets of S1P, such as Ca2+ and p38 MAPK (Meacci et al., 2002a; Porter et al., 2002; Cabane et al., 2003; Donati et al., 2005), could also play a role in the regulation of Cx43 expression induced by the bioactive lipid. To this end, we used BAPTA/AM (15 μM), a calcium chelator capable of preventing intracellular calcium increase, or SB239063 (5 μM), a specific inhibitor of p38 MAPK, and focused our observations on the time period where the effect of S1P on protein expression was predominant (48 h). As shown in Figure 3, depletion of Ca2+ by BAPTA/AM as well as inhibition of p38 MAPK activity by SB239063 prevented S1P-induced Cx43 up-regulation and strongly reduced expression of myogenin (Figure 3) and myosin heavy chain (MHC) and caveolin-3 (cav-3; unpublished data). Notably, no significant change was observed in the expression of Cx43 as well as of the other myogenic markers in myoblasts treated with PD98057 before S1P addition, suggesting that ERK1/2 activity was not required for Cx43 expression and myogenesis. Moreover, BAPTA/AM or PD98057 was unable to affect basal Cx43 and myogenin expression, whereas SB239063 strongly reduced Cx43 expression below the control. Taken together, these results indicated that S1P regulated the expression of Cx43 through the activation of both Ca2+- and p38 MAPK-dependent pathways.

Figure 3.

Effect of inhibition of calcium increase, ERK1/2, and p38 MAPK on S1P-induced Cx43 and myogenin expression in C2C12 myoblasts. (A) Confluent C2C12 cells were treated with 15 μM BAPTA/AM or 10 μM PD98059 or 5 μM SB239063 or each specific vehicle for 30 min before incubation in DM in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 1 μM S1P for 48 h. The content of Cx43 and myogenin were analyzed on cell lysates by Western blot. Equally loaded protein (30 μg) was checked by expression of the nonmuscle specific β-actin. Band intensity was determined by densitometry and relative percentage to control arbitrarily normalized to 100 is shown in the graphic. A blot representative of at least three independent experiments is shown.

Cx43 Protein Expression Is Required for Myoblast Differentiation Promoted by S1P

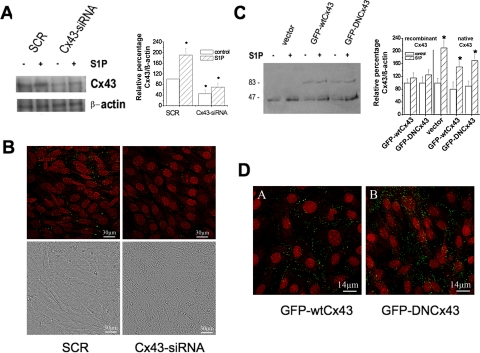

To investigate whether Cx43 expression represented an essential step in the myogenesis elicited by S1P, C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with a mix of specific siRNA duplexes directed against three distinct regions of mouse Cx43 mRNA or with plasmids encoding either for dominant negative mutant Cx43Δ130–136 or wild-type Cx43 fused to GFP (GFP-DNCx43, GFP-wtCx43) and examined for myogenic marker expression after 48 h of incubation in DM. Preliminary experiments were performed to verify the expression level of Cx43 in silenced and stable overexpressing myoblasts. As shown in Figure 4, A and B, Cx43 was significantly down-regulated in Cx43-siRNA-treated myoblasts both in unstimulated and stimulated cells. A band of ∼75 kDa, consistent with the predicted molecular weight of Cx43 protein fused to GFP, was immunodetected in GFP-DNCx43–, as well as in GFP-wtCx43–overexpressing myoblasts, and its expression appeared not to be affected by S1P treatment (Figure 4C). Confocal microscopy, performed to reveal the in situ localization of recombinant Cx43, showed that both GFP-wtCx43 and GFP-DNCx43 were present in the cytoplasm as well as at the plasma membrane. However, the localization of the mutated protein at cell–cell contacts, was less clear than that of wild-type Cx43, indicating some alterations in the organization of gap junctional plaques in GFP-DNCx43 myoblasts (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Effect of down-regulation and overexpression of wild-type and mutant Cx43. (A) Western analysis of Cx43 expression. C2C12 myoblasts treated with scrambled (SCR) or Cx43-siRNA were incubated with DM in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 1 μM S1P for 48 h. Proteins (30 μg) were separated on SDS-PAGE, and the content of Cx43 was analyzed using monoclonal anti-Cx43. Equally loaded proteins were evaluated as reported in Figure 3. Band intensity was determined as reported in the legend of Figure 1 and shown in the graphic. A blot representative of at least three independent experiments is shown. (B) Confocal microscopy of Cx43 expression. C2C12 cells treated with scrambled (SCR) or Cx43-siRNA were incubated in DM for 48 h in the presence of S1P. Cells were fixed and labeled for Cx43 to visualize the intracellular localization of Cx43 (green) and counterstained with PI (red) to reveal nuclei. Note the marked reduction of the fluorescence signal in Cx43-siRNA–treated myoblasts. Differential interference contrast images are shown to reveal the morphological features of SCR- or Cx43-siRNA–treated cells. (C) Western analysis of recombinant Cx43 expression. C2C12 myoblasts stably transfected with GFP-wtCx43 or GFP-DNCx43 or vector alone were incubated in DM for 48 h in the absence or presence of 1 μM S1P and processed as above. Recombinant protein and endogenous Cx43 were immunodetected by monoclonal anti-GFP and anti-Cx43 antibodies. Densitometric analysis determined as reported in Materials and Methods is shown in the graphic. A blot representative of three independent experiments is shown. (D) Confocal microscopy of recombinant Cx43 expression. C2C12 myoblasts stably transfected with wtCx43 (GFP-wtCx43) or DNCx43 (GFP-DNCx43) were incubated in DM for 48 h and processed as above. Recombinant wtCx43 immunostaining (green) was mainly detected as a linear punctate staining at the membrane interface in GFP-wtCx43 cells; in contrast, mutated Cx43 showed a predominant cytoplasmic localization in GFP-DNCx43 cells. The images are representative of three separate experiments with similar results.

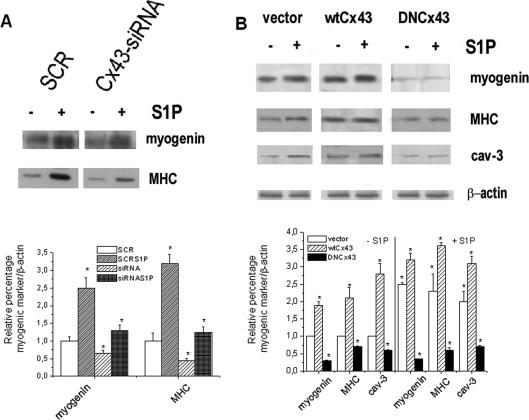

Interestingly, the down-regulation of the endogenous Cx43 protein or the enforced expression of mutated form dramatically reduced myogenic differentiation in control and S1P-stimulated cells, as judged by Western blot analysis for the expression of the myogenic markers (Figure 5, A and B) and by CK assay (3.3 ± 0.04 vs. 8.2 ± 0.09 U/mg in S1P-treated GFP-DNCx43 cells vs. S1P-stimulated C2C12 cells, p < 0.05, n = 3). In addition, both Cx43-siRNA-treated or GFP-DNCx43 cells showed a delay in myoblast maturation, retaining spherical or star-shaped morphology at 48 h of differentiation in the presence or absence of S1P (Figure 4B). By contrast, as shown in Figure 5B, enforced expression of GFP-wtCx43 accelerated C2C12 myoblast differentiation. All these data indicated that Cx43 expression and plasma membrane localization were required for skeletal muscle differentiation.

Figure 5.

Effect of down-regulation and overexpression of Cx43 on S1P-induced myogenic marker expression. (A) Western analysis of myogenic marker expression. Confluent C2C12 myoblasts were treated with scrambled (SCR) or Cx43-siRNA for 48 h in DM in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 1 μM S1P. Cell lysates (30 μg of protein) were separated by SDS-PAGE. Myogenin and MHC expression were immunodetected by specific antibodies. Equally loaded protein was checked by expression of the nonmuscle specific β-actin. Band intensity normalized with respect to each specific control (set as 100) is reported in the graphic. A blot representative of three independent experiments with similar results is shown. (B) Western analysis of myogenic marker expression. Confluent vector, GFP-wtCx43, or GFP-DNCx43 myoblasts incubated with DM for the indicated period of time in the absence (−) or in the presence (+) of 1 μM S1P were processed as reported above. Myogenin, MHC, and cav-3 expression were immunodetected by specific antibodies. Band intensity was determined by densitometry and relative percentage to control was arbitrarily normalized to 100 is shown in the graphic. A blot representative of at least three independent experiments with similar results is shown.

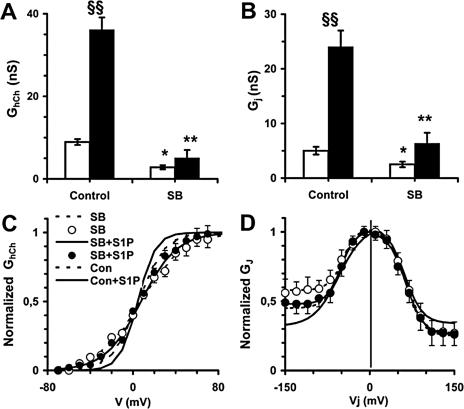

To understand the mechanisms by which Cx43 protein could regulate S1P-induced myogenesis, myoblasts overexpressing GFP-wtCx43 and GFP-DNCx43 were analyzed for the ability to form functional channels. Electrophysiological recordings of myoblast pairs cultured in DM in the presence or absence of S1P (Figure 6) indicated that the highest values of gap junction and hemichannel conductance were recorded in cells transfected with the wild-type connexin, suggesting that the overexpressed recombinant protein assembled correctly into functional connexons. Both basal gap junction and hemichannel conductance were reduced by ∼60% in GFP-DNCx43 myoblasts as compared with those of vector and C2C12 cells (Figure 6). In particular, C2C12 myoblasts overexpressing GFP-wtCx43 showed a symmetrical current-voltage plot, whereas those overexpressing GFP-DNCx43 exhibited an asymmetrical relationship as in control cells (Figure 6, Table 2). Similarly, the hemichannel voltage sensitivity increased in GFP-wtCx43- and decreased in GFP-DNCx43-expressing myoblasts (Figure 6, Table 2). Collectively, these data indicated a channel-dependent role for Cx43 in the regulation of skeletal myogenesis.

Figure 6.

Gap-junctional and hemichannel conductances in overexpressing myoblasts. (A and B) Gap junction, Gj,ss, and hemichannel, GhCh,ss, conductance. Electrophysiological parameters were measured in native C2C12 cells and in cells overexpressing GFP (Vector), GFP-DNCx43, and GFP-wtCx43. C2C12 cells cultured in DM in the presence (■) or absence of S1P (□) for 24 h were analyzed by dual (A) or single (B) patch clamp. Transfection with vector alone does not modify Gj,ss and GhCh,ss, whereas transfection with GFP-DNCx43 or with GFP-wtCx43 constructs decrease and increase both Gj,ss and GhCh,ss (*p < 0.05), respectively. S1P stimulation enhances the electrical coupling and hemichannel conductance in all the cell preparations (§p < 0.05 and §§p < 0.001). (C and D) Normalized Gj,ss-Vj plots. Note that S1P changes from asymmetrical to symmetrical the current-voltage plots in all the cell preparations, but not in GFP-DNCx43 cells. Open symbols are related to unstimulated cells (C), whereas filled symbols refer to S1P-stimulated cells (D). (Vector, Δ, ▴; GFP-wtCx43, □, ■; GFP-DNCx43, ○, ●). The related Boltzmann parameters are shown in Table 2. (E and F) Normalized GhCh,ss-V plots. Note that the hemichannel voltage sensitivity is markedly increased in GFP-wtCx43 cells compared with that of C2C12 and vector cells. Such increase is significantly enhanced by S1P stimulation (F, filled symbol) in all the cell preparations, but not in GFP-DNCx43 cells. Symbols and superimposed Boltzmann lines are as above. The related Boltzmann parameters are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Boltzmann parameters for gap junctions and hemichannels in overexpressing cells

| Parameter | Gap junctions |

Hemichannels |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −S1P |

+S1P |

|||||

| Vj(+) | Vj(−) | Vj(+) | Vj(−) | −S1P | +S1P | |

| A (mV−1) | 0.060 ± 0.004 | 0.070 ± 0.003 | 0.063 ± 0.004 | 0.058 ± 0.004ab | 0.08 ± 0.002 | 0.12 ± 0.002c |

| V0(mV) | 61.10 ± 4.42 | −50.01 ± 4.32a | 61.03 ± 5.02 | −54.03 ± 4.82a | 5.01 ± 0.8 | 4.61 ± 0.91 |

| Gmin | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 0.46 ± 0.05a | 0.34 ± 0.04b | 0.33 ± 0.04b | ||

| GFP-DNCx43 |

Hemichannels |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −S1P | +S1P | −S1P | +S1P | |||

| A (mV−1) | 0.068 ± 0.004 | 0.078 ± 0.003a | 0.066 ± 0.004 | 0.075 ± 0.004a | 0.05 ± 0.004d | 0.06 ± 0.004d |

| V0(mV) | 65.10 ± 4.42 | −48.11 ± 4.32a | 63.03 ± 5.02 | −50.03 ± 5.10a | 8.10 ± 1.2d | 7.03 ± 0.89d |

| Gmin | 0.24 ± 0.03 | 0.52 ± 0.05a | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 0.45 ± 0.04 | ||

| GFP-wtCx43 |

Hemichannels |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −S1P | +S1P | −S1P | +S1P | |||

| A (mV−1) | 0.063 ± 0.004 | 0.056 ± 0.003 | 0.062 ± 0.004 | 0.060 ± 0.004 | 0.14 ± 0.003e | 0.15 ± 0.003e |

| V0 (mV) | 62.10 ± 4.42 | −61.11 ± 4.32 | 62.03 ± 5.02 | −63.03 ± 5.02 | 4.11 ± 1.20 | 3.51 ± 0.75 |

| Gmin | 0.32 ± 0.03 | 0.33 ± 0.05 | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 0.30 ± 0.04 | ||

Data were obtained from vector, GFP-DNCx43 and GFP-wtCx43 cells incubated in DM for 24 h in the absence (−) or presence (+) of S1P. The parameters were obtained by fitting normalized Gj,ss and GhCh,ss vs. voltage data (15–20 recordings for each experimental condition). Gj,ss is asymmetrical in vector control and becomes symmetrical in S1P-treated cell pairs,

a p < 0.05 for Vj(−) vs. Vj(+), and

b p < 0.05 for S1P-stimulated vs. unstimulated cell pairs. In DN-Cx43 cells, Gj,ss remains asymmetrical after S1P stimulation, whereas in GFP-wtCx43 cells, Gj,ss is symmetrical in unstimulated and S1P-stimulated cells. As regards hemichannel parameters, in vector control cells, the value A, representing the GhCh,ss voltage sensitivity, is significantly increased in S1P-treated cells with respect to their control counterpart (

c p < 0.05). In GFP-DNCx43 and GFP-wtCx43 cells, the voltage sensitivity are significantly decreased or increased, respectively, with respect to vector control cells (

d p < 0.05,

e p < 0.05). Data presented as mean ± SEM.

The treatment with S1P caused a significant elevation of both the gap junction and hemichannel conductance in GFP-DNCx43 compared with vector cells (about twofold vs. 4–5-fold). Interestingly, the amplitude of Gjss and the Boltzmann parameters in S1P-treated GFP-DNCx43 cells did not differ from that of unstimulated vector and control myoblasts. However, it was of interest to note that 1) the residual gap junction and hemichannel conductance in GFP-DNCx43 cells stimulated with S1P showed, differently from control, a more pronounced asymmetrical behavior, suggesting the formation of connexons containing different combinations of the mutated and endogenous proteins in these experimental conditions; and 2) GFP-DNCx43 myoblasts were unable to undergo normal differentiation compared with control cells. Furthermore, the inhibition of p38 MAPK activity by the treatment with SB 239063 had effects on myogenin and gap and hemichannel conductance similar to those induced by the overexpression of GFP-DNCx43 (Figures 3 and 7 and Table 3).

Figure 7.

Effect of p38 MAPK-inhibition on gap junction and hemichannel conductance in C2C12 myoblasts. (A and B) Gap junction and hemichannel conductance. Gap junction, Gj,ss, and hemichannel, GhCh,ss, conductance was evaluated in unstimulated (□) or S1P-stimulated (■) C2C12 cells after incubation in DM for 24 h in the presence (SB) or absence (control) of 5 μM SB239063, added 30 min before S1P stimulation. In SB239063-treated cells, Gj,ss and GhCh,ss are significantly reduced (*p < 0.05), especially after S1P stimulation (**p < 0.01). The effect of S1P treatment on the electrical coupling and hemichannel conductance in control cells is statistically significant (§§p < 0.001). (C) Normalized Gj,ss-Vj plots. The treatment with SB239063 does not modify the current-voltage plot in unstimulated and S1P-stimulated cells. Open symbols and superimposed dashed lines refer to unstimulated cells, and filled symbols and continuous lines to S1P-stimulated cells. For comparison, continuous and dashed lines corresponding to the normalized Gj,ss of native cells are shown. The related Boltzmann parameters are listed in Table 3. (D) GhCh,ss-V plots. Note that S1P is unable to increase the hemichannel voltage sensitivity in SB239063-treated cells. Symbols and superimposed Boltzmann lines are as above. For comparison, continuous and dashed lines corresponding to normalized Ghch,ss of native cells are shown. The related Boltzmann parameters are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Boltzmann parameters for gap junctions and hemichannels in C2C12 cells treated with SB239063

| Parameter | Gap junctions |

Hemichannels |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SB |

SB + S1P |

|||||

| Vj(+) | Vj(−) | Vj(+) | Vj(−) | SB | SB + S1P | |

| A (mV−1) | 0.067 ± 0.004 | 0.082 ± 0.003a | 0.065 ± 0.004 | 0.078 ± 0.004a | 0.05 ± 0.003 | 0.06 ± 0.003 |

| V0 (mV) | 65.10 ± 4.42 | −48.11 ± 4.32a | 64.03 ± 5.02 | −51.03 ± 5.02a | 7.50 ± 1.2 | 7.0 ± 0.9 |

| Gmin | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 0.56 ± 0.05a | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.04a | ||

Data were obtained from unstimulated or S1P-stimulated C2C12 cells incubated in DM for 24 h with SB239063, which was added to the medium 30 min before S1P addition. The parameters were obtained by fitting normalized Gj,ss and GhCh,ss vs. voltage data (16–20 recordings for each experimental condition). Note that SB239063 does not modify Gj,ss,which remains asymmetrical after S1P treatment (

a p < 0.05). Moreover, S1P is unable to significantly change GhCh,ss. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Association of Cx43 with Cytoskeletal Proteins

In search of a possible explanation of the apparent discrepancy between the extent of gap junction permeability and myogenesis, and in consideration of the recent findings showing that Cx43 can affect cell function independently of gap junctional communication, we analyzed the ability of Cx43 protein to interact with other cellular proteins known to positively influence skeletal myogenesis, such as cytoskeletal proteins (Komati et al., 2005; Formigli et al., 2007).

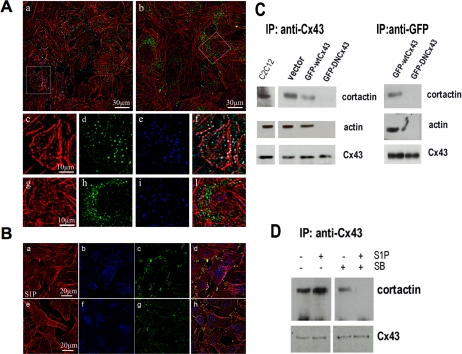

Colocalization of Cx43 with F-actin and cortactin, an F-actin–binding protein present in the cortical structures (Wu and Parsons, 1993; Wu and Montone, 1998), was investigated by confocal immunofluorescence followed by high-resolution deconvolution of the fluorescence images. Colabeling with Cx43 and anti-cortactin antibodies and/or TRITC-phalloidin revealed that the gap junctional protein colocalized with cortactin and, to a lesser extent, with F-actin in GFP-wtCx43–overexpressing cells (Figure 8A). By contrast, mutated Cx43 did not colocalized with F-actin and cortactin in basal conditions (unpublished data) as well as after S1P stimulation (Figure 8A). Similarly, the treatment with SB was able to prevent the interactions between F-actin and Cx43 in native C2C12 myoblasts (Figure 8B). The physical association of Cx43 with cytoskeletal proteins was verified by coimmunoprecipitation experiments. As shown in Figure 8C, endogenous Cx43 and GFP-wtCx43, but not GFP-DNCx43, coimmunoprecipitated with cortactin and skeletal actin. Of note, we found that S1P positively affected Cx43 interaction with cortactin in native C2C12 cells and such association was dependent on the activation of p38 MAPK pathways.

Figure 8.

Association between Cx43 and cytoskeletal proteins. (A) Intracellular localization of Cx43/actin complex in overexpressing C2C12 myoblasts. C2C12 cells were transfected with plasmids containing GFP-wtCx43 (a and c–f) or GFP-DNCx43 (b and g–l) grown in DM for 48 h, fixed, and stained with specific anti-cortactin antibodies (blue). Counterstaining was performed with TRITC-phalloidin (red) to show actin filaments. Fluorescent deconvolution microscopy analysis allowed the detection of F-actin (c and g) with Cx43 (green, d and h) and cortactin (e and i). (f–k) Merged images of F-actin, Cx43, and cortactin localization. White spots indicate colocalization of the three signals. Note that Cx43 colocalizes mainly with cortactin (cyan) and weakly with F-actin (yellow) in cells transfected with GFP-wtCx43, whereas the GFP-DNCx43 signal is found predominantly as green dots in the merged images, indicating the absence of colocalization with the cytoskeletal signals. (B) Intracellular localization of Cx43/actin complex in C2C12 myoblasts. C2C12 cells incubated in DM in the absence (a–d) or presence (e–h) of SB239063 (5 μM) 30 min before S1P addition were fixed and stained with specific anti-cortactin and anti-Cx43 antibodies. Counterstaining was performed with TRITC-phalloidin to show actin filaments. Fluorescent deconvolution microscopy analysis allowed the detection of F-actin (red, a and e) with Cx43 (blue, b and f) and cortactin (green, c and g). (d and h) Merged images of F-actin, Cx43, and cortactin localization. White spots indicate colocalization of the three signals. (C) Interaction of Cx43 with actin and cortactin in overexpressing C2C12 myoblasts. C2C12 cells were transfected with plasmids containing GFP-DNCx43 or GFP-wtCx43, incubated with DM for 48 h, and processed as described in Materials and Methods. Monoclonal anti-Cx43 or anti-GFP antibodies were incubated with cell lysates (200 μg of proteins) followed by immunoprecipitation (IP) with protein A-Sepharose beads. The bound proteins was eluted after extensive washing in Laemmli sample buffer followed by separation on SDS-PAGE and immunodetected using anti-cortactin or anti-actin or anti-Cx43 antibodies as indicated. A blot representative of at least three independent experiments with similar results is shown. (D) Effect of p38 MAPK-inhibition on Cx43 and cortactin interaction in S1P-stimulated C2C12 myoblasts. Confluent C2C12 cells were treated with 5 μM SB239063 or vehicle for 30 min before incubation in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 1 μM S1P and cultured for 48 h in DM. Cells were processed as above, and cortactin and Cx43 were immunodetected in the immunoprecipitate by specific anti-cortactin or anti-Cx43 antibodies. A blot representative of three independent experiments with similar results is shown.

All these data, taken together, were consistent with the idea that C2C12 myoblast differentiation could depend on the intercellular coupling as well as on an additional function of Cx43 protein per se, likely involving its physical interaction with proteins of cytoskeleton.

DISCUSSION

In the present study we identified Cx43 as a key regulatory protein of C2C12 myoblast differentiation elicited by S1P and proposed a novel mechanism by which Cx43 protein, in addition to form functional channels, may regulates skeletal muscle differentiation through other mechanisms requiring actin cytoskeletal remodeling and actin–Cx43 protein interaction.

In line with previous reports (Proulx et al., 1997a; Constantin and Cronier, 2000; Gorbe et al., 2005), Cx43 protein was transiently up-regulated in differentiating C2C12 myoblasts: Cx43 appeared early in proliferating cells, followed by a progressive increase in the cytoplasm and cell-membrane domains of adjacent myoblasts until fusion into myotubes, where the expression decreased rapidly. Moreover, we demonstrated that S1P was a potent inducer of Cx43 expression in these cells. This finding, together with our previous data showing that S1P is a stimulator of myogenesis in C2C12 cells (Donati et al., 2005), provides the basis for considering Cx43 protein as an new intracellular target of S1P action during myogenesis. Enhanced expression synthesis of Cx43 by S1P was accompanied by increased gap junctional communication, as demonstrated by Lucifer yellow dye transfer after microinjection and the evaluation of gap junctional conductance using dual patch-clamp method. In particular, the transjunctional currents between undifferentiated myoblastic pairs exhibited an asymmetrical voltage dependence, indicating the involvement of heterotypic gap junctional channels in C2C12 intercellular coupling as previously reported (Beyer, 1990; Brink et al., 1997; Sakai et al., 2003; Yao et al., 2003). Interestingly, the transjunctional current showed a symmetrical behavior in S1P-stimulated cells, consistent with the prevalence of Cx43-homotypic channels and the ability of the bioactive lipid to affect preferentially the expression of only one connexin isoform (i.e., Cx43). In agreement, the expression of Cx39, weakly detectable at basal level, was not affected by S1P in the early stages of myoblast differentiation. However, consistent with previous reports (von Maltzahn et al., 2004, 2006; Belluardo et al., 2005) the level of this protein increased in differentiated C2C12 cells, especially upon S1P treatment. We also demonstrated that S1P-dependent up-regulation of Cx43 was dependent on the intracellular p38 MAP kinase signaling and Ca2+ mobilization, in agreement with our previous data showing a clear correlation between Ca2+ concentration and Cx43 protein expression (Formigli et al., 2005a). On the other hand, we showed that S1P likely affected the degradative process of Cx43 in conditions where Ca2+ had been depleted and p38 MAP kinase was inhibited. Despite the evidence suggesting a role for ERK1/2 signaling pathway in the regulation of Cx43 expression (Warn-Cramer et al., 1998; Hossain et al., 1999), we showed here that ERK1/2 inactivation by PD98057 treatment did not modify the synthesis of the protein in C2C12 cells stimulated with S1P consistently with the reported inability of ERK1/2 inhibition to affect S1P-induced myogenesis in C2C12 cells (Donati et al., 2005).

Gap junctional communications have been long thought to play an important role in the coordination of numerous cell functions, including maintenance of the cellular homeostasis and the regulation of cell growth, differentiation, and development. In particular, several studies have proposed that gap junctions are required for skeletal muscle development and regeneration, because the blockade of the intercellular coupling with channel blockers, octanol and 18beta-glycyrrhetinic acid, or the inducible deletion of Cx43 in transgenic mice, inhibit the expression of myogenic markers in differentiating myoblasts (Kalderon et al., 1977; Araya et al., 2003). Based on these findings, it has been proposed a possible role for gap junctions in allowing the intercellular spread of second messengers and coordination of the cell functions in a network of cells (Simon and Goodenough, 1998). To verify whether the intercellular communication was critical during myogenesis in C2C12 cells, we silenced Cx43 expression, and prepared myoblasts expressing a dominant negative form of Cx43, which formed gap junction channels with reduced permeability. In both conditions we found that cells expressing mutated Cx43 failed to enter the myogenic program elicited by the bioactive lipid, supporting the idea that gap junction functionality was essential for the promotion of myogenesis by S1P. However, myogenesis appeared not to be fully dependent on the extent of gap junctional communication. In fact, it was found an almost complete inhibition of the expression of myogenic markers in GFP-DNCx43–expressing cells despite a 50% decrease in the transjunctional conductance compared with that of controls. Such discrepancy was even greater in GFP-DNCx43 myoblasts incubated with S1P for,one d, in which the gap junctional conductance was increased upon the basal levels and similar in amplitude to that of native unstimulated cells, which, instead, underwent normal differentiation. We explained the persistence of the cell-to-cell coupling in S1P-stimulated GFP-DNCx43 myoblasts by the ability of mutated connexin to form with the endogenous protein, up-regulated by the bioactive lipid, an ample range of connexons, whose function was dependent on the proportion of the endogenous and mutant form. It was likely that the different structure of connexons in S1P-treated GFP-DNCx43 cells compared with that of control cells (heteromeric vs. homomeric), despite the similar residual conductance, could explain the different capability to differentiate observed in the two cell populations. We suggested the possibility that Cx43 expression per se, in addition to its channel forming ability, could influence skeletal myogenesis of C2C12 cells elicited by S1P. Consistent with this assumption, several lines of evidences have recently shown that the expression of mutated Cx43 with no intrinsic channel activity are as effective as the wild-type protein in the regulation of several biological processes, including cell growth and survival (Lin et al., 1998; Dang et al., 2003). In such a view, it is very likely that Cx43, similarly to other proteins localized at the intercellular junctions, such as E-cadherin and β-catenin (Giepmans, 2004), may exert multiple functions with different domains and play an important role as intermediate protein in the transduction of signals from the membrane to nucleus.

Recent investigations have suggested an involvement for actin and actin-binding proteins in the regulation of myogenesis, and several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the effect of cytoskeleton on skeletal differentiation (Qu et al., 1997). Accumulating data have demonstrated a direct interaction of the Cx43 C-terminus, with cytoskeletal proteins displaying signal transduction activity, including drebrin (Butkevich et al., 2004), ZO-1 (zonula occludens 1 (Toyofuku et al., 2001), and c-Src (Giepmans et al., 2003). Therefore, we analyzed the ability of the mutated and wild-type protein to interact with the cytoskeleton. Of note, endogenous connexin and recombinant wild-type Cx43, but not DNCx43, were physically associated with skeletal actin as well as cortactin, strongly supporting the idea that the interaction between Cx43 protein and cytoskeleton may be involved in the accomplishment of myogenesis in C2C12 cells. We also showed that the interaction between the gap junction protein and cortactin is regulated by S1P and is dependent on p38 MAPK activation, pointing to the phosphorylation of Cx43 as an additional step in S1P regulation of gap junction protein function. The physical association of Cx43 with F-actin modulated by S1P is of particular interest in view of our recent observations, showing that actin remodeling is crucial for myogenic process elicited by S1P in the same cells (Formigli et al., 2005a; Formigli et al., 2007). Collectively, these data in combination with those reported in the literature showing that the lack of a correct gap-junctional assembly of Cx43 on the cell surface hampers several cellular processes, including growth, proliferation, and differentiation (Moorby and Patel, 2001; Dang et al., 2003; Li et al., 2006), are consistent with the emerging idea that Cx43 may also act as an adaptor protein and function through gap-independent mechanisms.

In conclusion, the results of the present study provide the first experimental evidence that up-regulation of Cx43 protein and the subsequent increase in gap junction functionality are important mechanism by which S1P promotes myogenesis in C2C12 myoblasts. Notably, our data, although not excluding that the exchange of molecules through functional gap junctions plays a dominant role in skeletal muscle differentiation, suggest that the interaction between Cx43 and cytoskeletal proteins may represent a possible molecular mechanism by which Cx43 per se affects cellular differentiation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. J. von Maltzahn and K. Willecke from Institut fur Genetik, Abteilung Molekulargenetik, Universitat Bonn, Germany, for providing us antibodies against the C-terminus region of mouse Cx39. This article was supported by grants from Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Pistoia e Pescia (to E.M.), from Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze (to F.F. and S.Z.-O.), and from the University of Florence (ex 60%) (to E.M., L.F., S.Z.-O., and F.F.).

Abbreviations used:

- S1P

sphingosine 1-phosphate

- wtCx43

wild-type connexin 43

- DNCx43

dominant negative connexin 43

- PBS

phosphate buffer solution

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- DM

differentiation medium

- HS

horse serum

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- ERK1/2

p44/42 MAPK

- siRNA

short interfering RNA

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- MHC

myosin heavy chain.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E06-03-0243) on September 6, 2006.

REFERENCES

- Araya R., Eckardt D., Maxeiner S., Kruger O., Theis M., Willecke K., Saez J. C. Expression of connexins during differentiation and regeneration of skeletal muscle: functional relevance of connexin43. J. Cell Sci. 2005;8:27–37. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araya R., Eckardt D., Riquelme M. A., Willecke K., Saez J. C. Presence and importance of connexin43 during myogenesis. Cell Commun. Adhes. 2003;10:451–456. doi: 10.1080/cac.10.4-6.451.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belluardo N., Trovato-Salinaro A., Mudo G., Condorelli D. F. Expression of the rat connexin 39 (rCx39) gene in myoblasts and myotubes in developing and regenerating skeletal muscles: an in situ hybridization study. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;320:299–310. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-1087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer E. C. Molecular cloning and developmental expression of two chick embryo gap junction proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:14439–14443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brink P. R., Cronin K., Banach K., Peterson E., Westphale E. M., Seul K. H., Ramanan S. V., Beyer E. C. Evidence for heteromeric gap junction channels formed from rat connexin43 and human connexin37. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:C1386–C1396. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butkevich E., Hulsmann S., Wenzel D., Shiraro T., Duden R., Majoul I. Drebrin is a novel connexin-43 binding partner that links gap junctions to the submembrane cytoskeleton. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:650–658. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukauskas F. F., Bukauskiene A., Bennett M. V., Verselis V. K. Gating properties of gap junction channels assembled from connexin43 and connexin43 fused with green fluorescent protein. Biophys. J. 2001;81:137–152. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75687-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabane C., Englaro W., Yeow K., Ragno M., Derijard B. Regulation of C2C12 myogenic terminal differentiation by MKK3/p38alpha pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C658–C666. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00078.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantin B., Cronier L. Involvement of gap junctional communication in myogenesis. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2000;196:1–65. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(00)96001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang X., Doble B. W., Kardami E. The carboxy-tail of connexin-43 localizes to the nucleus and inhibits cell growth. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2003;242:35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donati C., Meacci E., Nuti F., Becciolini L., Farnararo M., Bruni P. Sphingosine 1-phosphate regulates myogenic differentiation: a major role for S1P2 receptor. FASEB J. 2005;19:449–451. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1780fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formigli L. Morphofunctional integration between skeletal myoblasts and adult cardiomyocytes in coculture is favored by direct cell-cell contacts and relaxin treatment. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2005a;288:C795–C804. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00345.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formigli L. Sphingosine 1-phosphate induces cytoskeletal reorganization in C2C12 myoblasts: physiological relevance for stress fibres in the modulation of ion current through stretch-activated channels. J. Cell Sci. 2005b;118:1161–1171. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formigli L., Meacci E., Sassoli C., Squecco R., Nosi D., Chellini F., Naro F., Francini F., Zecchi Orlandini S. Actin cytoskeleton/stretch-activated ion channels interaction regulates myogenic differentiation of skeletal myoblasts. J. Cell Physiol. 2007 doi: 10.1002/jcp.20936. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giepmans B. N. Gap junctions and connexin-interacting proteins. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004;62:233–245. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giepmans B. N., Feiken E., Gebbink M. F., Moolenaar W. H. Association of connexin43 with a receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase. Cell Commun. Adhes. 2003;10:201–205. doi: 10.1080/cac.10.4-6.201.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg G. S., Lampe P. D., Nicholson B. J. Selective transfer of endogenous metabolites through gap junctions composed of different connexins. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1:457–459. doi: 10.1038/15693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbe A., Becker D. L., Dux L., Stelkovics E., Krenacs L., Bagdi E., Krenacs T. Transient upregulation of connexin43 gap junctions and synchronized cell cycle control precede myoblast fusion in regenerating skeletal muscle in vivo. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2005;123:573–583. doi: 10.1007/s00418-004-0745-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grounds M. D., White J. D., Rosenthal N., Bogoyevitch M. A. The role of stem cells in skeletal and cardiac muscle repair. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2002;50:589–610. doi: 10.1177/002215540205000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawke T. J., Garry D. J. Myogenic satellite cells: physiology to molecular biology. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001;91:534–551. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.2.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M. Z., Jagdale A. B., Boynton A. L. Mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphorylation of connexin43 are not sufficient for the disruption of gap junctional communication by platelet-derived growth factor and tetradecanoylphorbol acetate. J. Cell Physiol. 1999;179:87–96. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199904)179:1<87::AID-JCP11>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G. Y., Cooper E. S., Waldo K., Kirby M. L., Gilula N. B., Lo C. W. Gap junction-mediated cell-cell communication modulates mouse neural crest migration. J. Cell Biol. 1998a;143:1725–1734. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R. P., Fan Y., Hossain M. Z., Peng A., Zeng Z. L., Boynton A. L. Reversion of the neoplastic phenotype of human glioblastoma cells by connexin 43 (cx43) Cancer Res. 1998b;58:5089–5096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalderon N., Epstein M. L., Gilula N. B. Cell-to-cell communication and myogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 1977;75:788–806. doi: 10.1083/jcb.75.3.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaliman P., Canicio J., Testar X., Palacin M., Zorzano A. Insulin-like growth factor-II, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, nuclear factor-kappaB and inducible nitric-oxide synthase define a common myogenic signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:17437–17444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komati H., Naro F., Mebarek S., De Arcangelis V., Adamo S., Lagarde M., Prigent A. F., Nemoz G. Phospholipase D is involved in myogenic differentiation through remodeling of actin cytoskeleton. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:1232–1244. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-06-0459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo R. P., Wang S. Y., John S. A., Weiss J. N., Goldhaber J. I. Metabolic inhibition activates a non-selective current through connexin hemichannels in isolated ventricular myocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2000;32:1859–1872. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krutovskikh V. A., Yamasaki H., Tsuda H., Asamoto M. Inhibition of intrinsic gap junction intercellular communication and enhancement of tumorigenicity of the rat bladder carcinoma cell line BC31 by a dominant-negative connexin 43 mutant. Mol. Carcinog. 1998;23:254–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J. X., Gu S. Gap junction- and hemichannel-independent actions of connexins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1711:208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassar A. B., Buskin J. N., Lockshon D., Davis R. L., Apone S., Hauschka S. D., Weintraub H. MyoD is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein requiring a region of myc homology to bind to the muscle creatine kinase enhancer. Cell. 1989;58:823–831. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90935-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Zhou Z., Saunders M. M., Donahue H. J. Modulation of connexin43 alters expression of osteoblastic differentiation markers. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C1248–C1255. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00428.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J. H., Weigel H., Cotrina M. L., Liu S., Bueno E., Hansen A. J., Hansen T. W., Goldman S., Nedergaard M. Gap junction-mediated propagation and amplification of cell injury. Nat. Neurosci. 1998;1:743–749. doi: 10.1038/2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meacci E., Becciolini L., Nuti F., Donati C., Cencetti F., Farnararo M., Bruni P. A role for calcium in sphingosine 1-phosphate-induced phospholipase D activity in C2C12 myoblasts. FEBS Lett. 2002a;521:200–204. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02866-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meacci E., Cencetti F., Formigli L., Squecco R., Donati C., Tiribilli B., Quercioli F., Zecchi Orlandini S., Francini F., Bruni P. Sphingosine 1-phosphate evokes calcium signals in C2C12 myoblasts via Edg3 and Edg5 receptors. Biochem. J. 2002b;362:349–357. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3620349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meacci E., Cencetti F., Donati C., Nuti F., Farnararo M., Kohno T., Igarashi Y., Bruni P. Down-regulation of EDG5/S1P2 during myogenic differentiation results in the specific uncoupling of sphingosine 1-phosphate signalling to phospholipase D. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1633:133–142. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(03)00106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorby C., Patel M. Dual functions for connexins: Cx43 regulates growth independently of gap junction formation. Exp. Cell Res. 2001;271:238–248. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naro F., Sette C., Vicini E., De Arcangelis V., Grange M., Conti M., Lagarde M., Molinaro M., Adamo S., Nemoz G. Involvement of type 4 cAMP-phosphodiesterase in the myogenic differentiation of L6 cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1999;10:4355–4367. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.12.4355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omori Y., Yamasaki H. Mutated connexin43 proteins inhibit rat glioma cell growth suppression mediated by wild-type connexin43 in a dominant-negative manner. Int. J. Cancer. 1998;78:446–453. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19981109)78:4<446::aid-ijc10>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter G. A., Jr, Makuck R. F., Rivkees S. A. Reduction in intracellular calcium levels inhibits myoblast differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:28942–28947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203961200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proulx A. M., Merrifield P. A., Naus C. C. Blocking gap junctional intercellular communication in myoblasts inhibits myogenin and MRF4 expression. Dev. Genet. 1997a;20:133–144. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1997)20:2<133::AID-DVG6>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proulx A. A., Lin Z. X., Naus C. C. Transfection of rhabdomyosarcoma cells with connexin43 induces myogenic differentiation. Cell Growth Differ. 1997b;8:533–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin H., Shao Q., Curtis H., Galipeau J., Belliveau D. J., Wang T., Alaoui-Jamali M. A., Laird D. W. Retroviral delivery of connexin genes to human breast tumor cells inhibits in vivo tumor growth by a mechanism that is independent of significant gap junctional intercellular communication. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:29132–29138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200797200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu G., Yan H., Strauch A. R. Actin isoform utilization during differentiation and remodeling of BC3H1 myogenic cells. J. Cell Biochem. 1997;67:514–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saba J. D. Lysophospholipids in development: miles apart and edging in. J. Cell Biochem. 2004;92:967–992. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sàez J. C., Berthoud V. M., Branes M. C., Martinez A. D., Beyer E. Plasma membrane channels form by connexin: their regulation and function. Physiol. Rev. 2003;83:1359–1400. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai R., Elfgang C., Vogel R., Willecke K., Weingart R. The electrical behaviour of rat connexin46 gap junction channels expressed in transfected HeLa cells. Pfluegers Arch. 2003;446:714–727. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon A. M., Goodenough D. A. Diverse functions of vertebrate gap junctions. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:477–483. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01372-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh D., Solan J. L., Taffet S. M., Javier R., Lampe P. D. Connexin 43 interacts with zona occludens-1 and -2 proteins in a cell cycle stage-specific manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:30416–30421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506799200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout C., Goodenough D. A., Paul D. L. Connexins: functions without junctions. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2004;16:507–512. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyofuku T., Akamatsu Y., Zhang H., Kuzuya T., Tada M., Hori M. c-Src regulates the interaction between connexin-43 and ZO-1 in cardiac myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:1780–1788. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005826200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upham B. L., Suzuki J., Chen G., Trosko J. E., Wang Y., McCabe L. R., Chang C. C., Krutovskikh V. A., Yamasaki H. Reduced gap junctional intercellular communication and altered biological effects in mouse osteoblast and rat liver oval cell lines transfected with dominant-negative connexin 43. Mol. Carcinog. 2003;37:192–201. doi: 10.1002/mc.10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]