Abstract

Myo1c is a member of the myosin superfamily that binds phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), links the actin cytoskeleton to cellular membranes and plays roles in mechano-signal transduction and membrane trafficking. We located and characterized two distinct membrane binding sites within the regulatory and tail domains of this myosin. By sequence, secondary structure, and ab initio computational analyses, we identified a phosphoinositide binding site in the tail to be a putative pleckstrin homology (PH) domain. Point mutations of residues known to be essential for polyphosphoinositide binding in previously characterized PH domains inhibit myo1c binding to PIP2 in vitro, disrupt in vivo membrane binding, and disrupt cellular localization. The extended sequence of this binding site is conserved within other myosin-I isoforms, suggesting they contain this putative PH domain. We also characterized a previously identified membrane binding site within the IQ motifs in the regulatory domain. This region is not phosphoinositide specific, but it binds anionic phospholipids in a calcium-dependent manner. However, this site is not essential for in vivo membrane binding.

INTRODUCTION

Myosin-Is are single-headed motor proteins that make up the largest unconventional myosin family in humans (Berg et al., 2001). They are widely expressed and function in membrane dynamics, cell structure, and mechanical signal transduction by linking the actin cytoskeleton to cellular membranes (Ruppert et al., 1995; Tang and Ostap, 2001; Bose et al., 2002; Holt et al., 2002; Tyska et al., 2005). Subcellular fractionations of vertebrate cells show that a large percentage of myosin-I is associated with the membrane and the cytoskeletal fractions (Ruppert et al., 1995; Bose et al., 2002), and immunofluorescence and live cell microscopy suggest that myosin-I is dynamically localized to the cell membrane. Thus, a key property of myosin-I isoforms seems to be their ability to bind in a regulated manner to cellular membranes (Coluccio, 1997; Tang and Ostap, 2001).

In vitro biochemical experiments provide evidence that myosin-I binds anionic phospholipids via electrostatic interactions (Adams and Pollard, 1989; Miyata et al., 1989; Hayden et al., 1990), and in vivo experiments have suggested that myosin-I isoforms associate with anionic phosphoinositides (Hirono et al., 2004; Huang et al., 2004). Our recent experiments have shown that a widely expressed vertebrate myosin-I isoform, myo1c, associates with high-affinity to phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) via a site in the myosin-I tail domain (Hokanson and Ostap, 2006). This interaction is clearly different from the cooperative interactions of membrane binding proteins that contain polybasic effector domains, e.g., MARCKS (McLaughlin et al., 2002) and N-WASP (Papayannopoulos et al., 2005), and seems to be noncooperative and specific for the headgroup of the lipid, similar to the interaction between pleckstrin homology (PH) domains and phosphoinositides (for review, see Lemmon and Ferguson, 2001).

Although we determined that the PIP2 binding site resides in the tail domain of myo1c, the specific sequences responsible for binding have not been identified. Additionally, it has been proposed that membrane binding also can be mediated via the myosin-I regulatory domain (Swanljung-Collins and Collins, 1992; Tang et al., 2002; Hirono et al., 2004), which is composed of three positively charged IQ motifs. IQ motifs are sequences of 21–25 amino acids that bind calmodulin and calmodulin-like proteins (Bahler and Rhoads, 2002). Anionic phospholipids may compete with calmodulin for binding to the positive residues in the IQ motifs in a calcium-sensitive manner (Tang et al., 2002; Hirono et al., 2004). The relevance of this binding has not been determined. Quantitative binding experiments must be performed and correlated with in vivo observations to clarify the role of the regulatory domain in membrane attachment.

In this study, we report the identification of the PIP2 binding site as a putative PH domain in the myo1c tail. This domain seems to be present in most myosin-I isoforms and is necessary for in vivo membrane association. Additionally, we report that the myo1c regulatory domain binds nonphysiologically high concentrations of anionic lipids in a calcium-dependent manner, but it does not bind to phosphoinositides specifically and is not a major determinant of binding in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and Buffers

All in vitro experiments were performed in HNa100 (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, and 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT]). Calcium concentrations were adjusted by adding CaCl2 to HNa100 and are reported as free calcium. Unless stated otherwise, all binding experiments were performed with 1 μM free calmodulin. Phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidylcholine (PC), and PIP2 were from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL); d-myo-inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate [Ins(1,4,5)P3], d-myo-inositol-1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate [Ins(1,3,4,5)P4], d-myo-inositol-1,3,4,6-tetrakisphosphate [Ins(1,3,4,6)P4], and d-myo-inositol hexakisphosphate (InsP6) were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA); d-myo-inositol-3-monophosphate [Ins(3)P1], d-myo-inositol-1,3,4-trisphosphate [Ins(1,3,4)P3], and d-myo-inositol-1,2,6-trisphosphate [Ins(1,2,6)P3] were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI); d-myo-inositol-1,2,5,6-tetrakisphosphate [Ins(1,2,5,6)P4], and d-myo-inositol-1,2,3,5,6-pentakisphosphate [Ins(1,2,3,5,6)P5] were purchased from A.G. Scientific (San Diego, CA). Recombinant chicken calmodulin was expressed and purified from bacterial lysates (Putkey et al., 1985) and further purified by fast-performance liquid chromatography as described previously (Hokanson and Ostap, 2006).

Baculovirus Expression Constructs

Most binding experiments were performed using protein expressed in Sf9 cells coinfected with baculovirus containing the myo1c construct and baculovirus containing calmodulin. A mouse myo1c-tail construct (accession no. NM_008659) containing residues 690-1028 (myo1c-tailIQ1-3), which consists of an N-terminal HIS6 tag for purification, three calmodulin-binding IQ motifs, and the tail domain, was expressed and purified as described previously (Tang et al., 2002). A mouse myo1c-motor-IQ construct containing residues 1–767 (myo1c-motorIQ1-3), which includes the motor domain, three calmodulin-binding IQ motifs, and C-terminal tag for site-specific biotinylation and FLAG sequence for purification, was expressed and purified as described previously (Hokanson and Ostap, 2006).

Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) Expression Constructs and GFP Protein Purification

GFP-tagged mouse myo1c-tail constructs were created in the plasmid pEGFP-C1 (Clonetech, Mountain View, CA). Expression constructs contain an N-terminal GFP, the myo1c-tail domain, and the first three IQ motifs (residues 690-1028; GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3), the second two IQ motifs (residues 721-1028; GFP-myo1c-tailIQ2–3), the third IQ motif (residues 744-1028; GFP-myo1c-tailIQ3), no IQ motifs (residues 768-1028; GFP-myo1c-tailIQ0). Full-length myo1c (GFP-myo1c) was created in the plasmid pEGFP-N1.

Point mutations in GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3 (GFP-K892A and GFP-R903A) or full-length GFP-myo1c (GFP-myo1c-K892A and GFP-myo1c-R903A) were generated using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). All point mutations were verified by automated dideoxynucleotide sequencing.

Small amounts of GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3, GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3-K892A, and GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3-R903A were purified for binding experiments by transient expression in human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293T cells. Transfected cells (∼1 × 109 cells per transfection) were collected by sedimentation, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. GFP proteins were purified in a 1-d procedure. Pellets of ∼1 × 109 cells were suspended in 15 ml of lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, 1 mM EGTA, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.5% Igepal, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.01 mg/ml aprotinin, and 0.01 mg/ml leupeptin), lysed by 8 strokes in a Dounce homogenizer, and centrifuged for 1 h at 100,000 × g. The supernatant was incubated on ice with 10 μg/ml RNase A and 5 μg/ml DNase I for 20 min. After dilution, the final NaCl concentration of the supernatant was 100 mM. It was then passed through a 0.22-μm syringe filter and loaded immediately onto a monoQ column (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). Protein was eluted from the monoQ column by using a linear salt gradient, and GFP proteins were detected by monitoring GFP fluorescence. Fractions containing GFP were diluted to 100 mM final NaCl concentration, and CaCl2 was added to attain 1 mM free calcium. The protein was loaded immediately back on the monoQ column and eluted with a linear salt gradient in column buffers containing 1 mM free calcium. Addition of calcium results in the dissociation of a calmodulin from myo1c (Zhu et al., 1998; Sokac and Bement, 2000). We found that this dissociation causes the GFP proteins to elute from the monoQ column at a lower salt concentration, resulting in their separation from calcium-insensitive proteins. Calmodulin (5 μM) and 5 mM EGTA were added to the eluted GFP proteins, and the proteins were dialyzed overnight versus HNa100. GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3, GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3-K892A, and GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3-R903A were >90% pure as determined by Sypro-red staining of SDS-PAGE gels (Figure 2, inset). GFP proteins were stored on ice and used in binding assays within 2 d of purification. Yields of pure GFP proteins were low (2–3 μg per transfection), but the preparations provided enough material to perform binding assays.

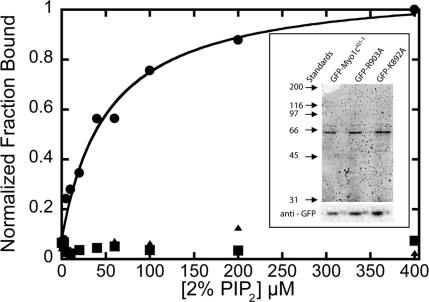

Figure 2.

Lipid concentration dependence of 6.9 nM GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3 (●), 9.7 nM GFP-K892A (■), and 15 nM GFP-R903A (▴) binding to LUVs composed of 2% PIP2. Each point is the average of two measurements. The solid line is the best fit of the GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3 data to a hyperbola, yielding, Kefflipid = 53 ± 11 μM. Top inset, Sypro-red stained SDS-PAG showing purified GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3, GFP-R903A, and GFP-K892A. Bottom inset, immunoblot of purified GFP-myo1c-tail constructs stained with anti-GFP antibody.

Lipid Preparation and Sedimentation Assays

Large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) with 100-nm diameter were prepared by extrusion as described previously (Hokanson and Ostap, 2006). Briefly, lipid components were mixed in the desired ratios in chloroform and dried under a stream of N2. Dried lipids were resuspended in 176 mM sucrose and 12 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, subjected to five cycles of freeze-thaw, and then bath sonicated 1 min before being extruded through 100-nm filters and dialyzed overnight versus HNa100. LUVs were stored at 4°C under N2 and discarded after 3 d. PS and PIP2 percentages reported throughout the text are the mole percentages of total PS and PIP2 with the remainder being PC. Lipid concentrations are given as total lipid unless otherwise noted.

Binding of myo1c constructs to LUVs was determined by sedimentation assays as described previously (Hokanson and Ostap, 2006). Briefly, 200-μl samples containing sucrose-loaded LUVs and myo1c constructs were sedimented at 150,000 × g for 30 min at 25°C. The top 160 μl of each sample was removed and analyzed as supernatant. Pellets to be analyzed by SDS-PAGE were resuspended with 10 μl of SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiled. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with SYPRO-red (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for quantitation as described previously (Hokanson and Ostap, 2006). Supernatants containing GFP proteins were assayed for GFP fluorescence in a fluorometer (PTI, Birmingham, NJ).

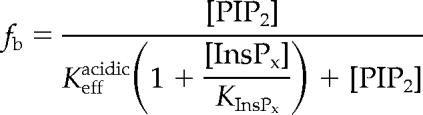

We report the binding affinity of myo1c protein constructs to LUVs as an effective dissociation constant in terms of total lipid concentration (Kefflipid) or in terms of the accessible acidic phospholipid concentration (Keffacidic). Kefflipid is simply the inverse of the partition coefficient as defined (Peitzsch and McLaughlin, 1993). Binding data were fit to hyperbolae by using KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software, Reading, PA). Soluble inositol phosphate competition data were fit to the following equation:

|

where [PIP2] is the concentration of accessible PIP2, [InsPx] is the concentration of the soluble inositol phosphate, KInsPx is the affinity of the inositol phosphate for myo1c, and Keffacidic is the effective dissociation constant of the myo1c-PIP2 interaction in terms of accessible concentration of PIP2.

Live Cell Microscopy and Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF)/Fluorescence-Recovery after Photobleaching (FRAP)

Normal rat kidney (NRK) epithelial cells were cultured and electroporated with GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3, GFP-myo1c-tailIQ2–3, GFP-myo1c-tailIQ3, GFP-myo1c-tailIQ0, GFP-myo1c, GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3-K892A, GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3-R903A, GFP-myo1c-K892A, GFP-myo1c-R903A, or GFP only as described previously(Tang and Ostap, 2001). To avoid apparent aggregation of GFP-myo1c-tailIQ0, cells electroporated with this construct were grown overnight at 32°C. Cells plated on 40-mm glass coverslips were mounted in a temperature-controlled flow chamber (Bioptechs, Butler, PA) for microscopic observation and perfused with DMEM, 10 mM HEPES, and 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C as described previously (Tang and Ostap, 2001).

Objective-type TIRF microscopy was performed on a modified Leica DMIRB microscope fitted with a Nikon 1.45 numerical aperture objective (Axelrod, 2001). Samples were illuminated through the rear port of the microscope with a 488-nm laser beam (Melles Griot, Carlsbad, CA) focused on the back focal plane of the objective. Images were acquired with a digital camera (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ) and MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). A computer controlled filter wheel (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) containing neutral density filters was placed in the beam path to allow for attenuation of the beam. Photobleaching by TIRF illumination was accomplished by removing the neutral density filter and decreasing the beam diameter. FRAP was performed as follows. Five prebleach TIRF images were acquired 5–10 s apart with a 100-ms acquisition time, followed by a 1-s bleaching TIRF pulse, followed by the immediate acquisition of images 1–2.5 s apart with 100-ms acquisition time. The bleach illumination was 10- to 100-fold more intense (depending on the cell intensity) than the imaging illumination.

For presentation purposes (Figure 3), the photobleached region was normalized by dividing the image by the same region acquired 20–30 s before the bleach pulse and then multiplied by 1000 to allow visualization of a 12-bit image. This normalization allows the fluorescence recovery to be visualized without the complication of cell intensity variation. Movies of the fluorescence recovery without normalization are available in the supplementary information.

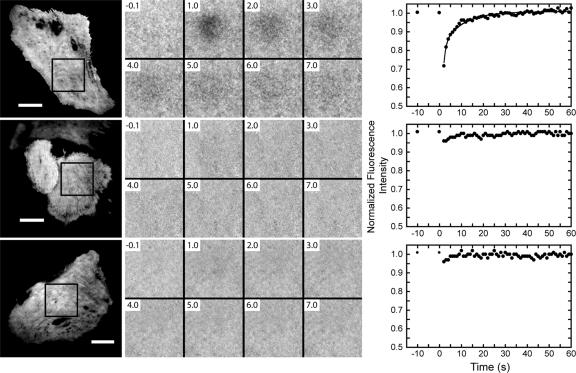

Figure 3.

TIRF/FRAP experiments of single NRK cells expressing GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3 (top row), GFP-K892A (middle row), and GFP-R903A (bottom row). Left, TIRF micrographs of NRK cells before photobleaching. The boxes outline the photobleached regions. Bar, 15 μm. Middle, normalized time-lapse images of the photobleached regions (see Materials and Methods); elapsed times are given relative to the start of the bleach pulse. Right, fluorescence recovery of GFP after photobleach. The bleach pulse occurs at time 0. The solid line in the top graph is a fit of the data from this cell to the sum of two exponential rates (kslow = 0.10 ± 0.010 s−1). Movies of the fluorescence recovery without normalization are available in Supplemental Materials.

For analysis, the average background intensity was subtracted from the image, and the integrated intensity of the bleached spot was normalized by dividing by the intensity before the bleach. Thus, the intensity of the spot before the bleach is set to 1, and absence of fluorescence is set to zero. After the bleaching pulse, the illumination required for visualization of the recovery time course resulted in further photobleaching (<15%) in some cells. This non-FRAP bleaching was corrected for by subtracting the rate of photobleaching as determined in an area away from the FRAP region. The effective rate of fluorescence recovery was determined by fitting the recovery transient to the sum of two exponential rates by using KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software).

Molecular Modeling and Structure Prediction

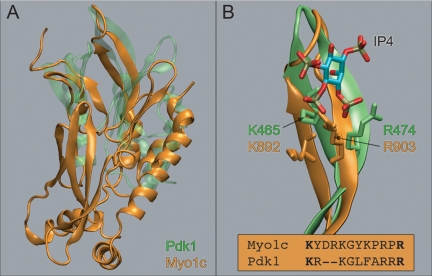

We used the Phyre server (www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/phyre/) to initially discover the secondary structural similarities of the tail domain to a PH domain. The Phyre server predicts the three-dimensional structure of a protein sequence by “threading” it through known structures and scoring it for compatibility (Kelley et al., 2000). To provide further speculative structural insight into the binding of PIP2 by the myosin-I tail, we ran the mouse myo1c sequence through Pfam to identify known domains (Bateman et al., 2004). Based on the Pfam analysis, we selected a region following the IQ motif as the tail region (P802-R1028) and used this sequence in ab initio structure prediction with Rosetta (Bonneau et al., 2002), generating a total of 50 structures. Clustering the structural predictions based on root mean square deviation (RMSD) resulted in a top structural candidate, and the side chains of this structure were added in and minimized using PLOP (Jacobson et al., 2004). This completed structure was then simulated using molecular dynamics in Gromacs 3.3 (Lindahl et al., 2001). The simulation used the OPLS/AA force field, TIP3P water, and periodic boundary conditions with Particle Mesh Ewald for long-range electrostatics. After heating the system in 50K steps and equilibrating for 1 ns, the structure was simulated for a total of 20 ns at 300K. There were some minimal structural rearrangements during the simulation, but the basic structure of the protein remained constant throughout the simulation. Finally, to identify potential structural homologues, we performed a BLAST search on the myo1c-tail sequence, identifying phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (Pdk1) as a limited sequence match. Because Pdk1 had been crystallized with Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 (pdb 1W1D) and our myo1c tail sequence showed 61% identity over the PIP2 binding region of Pdk1, we used this structure for a detailed structural comparison.

RESULTS

Identification of a Putative PH Domain in the Myo1c Tail

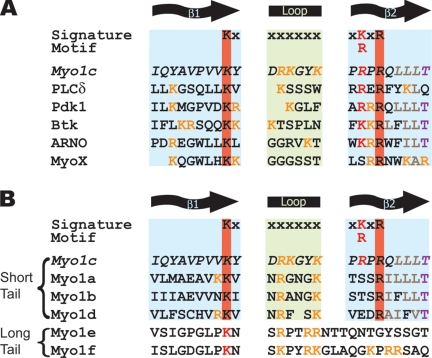

We searched for structural homologues of the myo1c tail domain by using the Phyre server (www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/phyre/) with the goal of identifying a phosphoinositide binding site. Secondary structural analysis reveals that the myo1c-tail domain has homology to PH domains, including specific sequence homology to the β1-loop-β2 phosphoinositide binding region of certain PH domains (Isakoff et al., 1998). This region contains the PH domain signature motif of conserved basic residues [K-Xn-(K/R)-X-R] (Isakoff et al., 1998; Cronin et al., 2004), which we identify in myo1c (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Alignment of mouse myo1c (residues 884–908) with the β1-loop-β2 motif of PH domains (A) and other myosin-I isoforms (B). Red bands and residues indicate conserved basic residues important for membrane binding in PH domains, orange residues indicate all other basic residues, brown residues indicate conserved hydrophobic patch after the second key residue of β2, purple residues indicate conserved threonine at end of β2. Accession numbers for the proteins listed are as follows: PLCδ (M20637), Pdk1 (AF017995), Btk (L29788), Arf nucleotide binding site opener (ARNO; PR000904), Myosin X (U55042), myo1a (AF009961), myo1b (X68199), myo1c (NP032685), myo1d (X71997), myo1e (U14391), and myo1f (X97650).

Two of the conserved basic residues in the β1-loop-β2 region of PH domains have been shown to be crucial for high-affinity polyphosphoinositide binding (Cronin et al., 2004) (shown as red residues in Figure 1A). To determine whether these residues also play a role in myo1c-PIP2 interactions, we mutated the corresponding amino acids in a GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3 construct (which includes three IQ motifs and bound calmodulins) to alanines (GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3-K892A and GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3-R903A). We expressed GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3, GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3-K892A, and GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3-R903A in HEK-293T cells, and purified the proteins using a simple two-step purification (see Materials and Methods; Figure 2, inset).

We determined the effective dissociation constants, expressed in terms of total lipid (Kefflipid) or accessible acidic phospholipid (Keffacidic), for the interaction between GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3 GFP-K892A, and GFP-R903A and sucrose-loaded LUVs containing 2% PIP2 by sedimentation (Table 1). Because the constructs are GFP fusion proteins, we were able to determine the fraction bound as a function of lipid concentration by monitoring the loss of fluorescence in the supernatant (Figure 2). The GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3 binds with Kefflipid = 53 ± 11 μM (Keffacidic = 0.53 ± 0.11 μM; Table 1), which is approximately twofold weaker than a myo1c-tailIQ1-3 construct expressed in Sf9 cells that does not contain GFP (Table 1; Hokanson and Ostap, 2006). Remarkably, we did not detect any binding of the GFP-K892A and GFP-R903A mutants to LUVs containing 2% PIP2 at lipid concentrations up to 400 μM (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Effective dissociation constants for myo1c-tail binding to LUVsa

| Myo1c construct | LUV compositionb | Kefflipid (μM)c | Keffacidic (μM)d |

|---|---|---|---|

| GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3 | 2% PIP2 | 53 ± 11 | 0.53 ± 0.11 |

| GFP-K892A | 2% PIP2 | ≫400 | ≫4 |

| GFP-R903A | 2% PIP2 | ≫400 | ≫4 |

| Myo1c-tailIQ1-3 | 2% PIP2 | 23 ± 5.0e | 0.23 ± 0.050e |

| Myo1c-tailIQ1-3 | 2% PIP2 + 20% PS | 4.0 ± 1.5 | 0.44 ± 0.17 |

a 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, and 1 μM calmodulin.

b Mole percentages of PS and PIP2 are reported with the remaining composed of PC.

c Effective dissociation constants expressed in terms of total phospholipid. Errors are SEs of the fit.

d Effective dissociation constants expressed in terms of accessible acidic phospholipid. Errors are SEs of the fit.

e Data from Hokanson and Ostap (2006).

We monitored membrane association of GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3, GFP-K892A, and GFP-R903A by TIRF/FRAP microscopy in live NRK cells to determine whether the K892A and R903A mutations affect in vivo membrane binding. The fluorescence of all constructs was visible by TIRF microscopy, as was fluorescence from cells expressing GFP only (our unpublished data). The fluorescence after photobleaching of GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3 recovered in two phases (Figure 3). A fast phase (kfast) recovered within the first acquisition point (>1 s−1), and a slow phase (kslow) recovered with an average rate of 0.060 ± 0.037 s−1 (Figure 3 and Table 2). kslow ranged between 0.013 and 0.15 s−1 (Table 2) in the 18 cells examined by TIRF/FRAP, but in all cases kslow was clearly resolved from kfast. Because myo1c binds to acidic lipids with a diffusion-limited rate (Tang et al., 2002), we interpret the slow recovery time to be the rate at which the photobleached GFP-tagged-myo1c dissociates from the membrane and the fast recovery to be the diffusion of GFP-tagged-myo1c in the cytoplasm (Tyska and Mooseker, 2002).

Table 2.

Rates of fluorescence recovery from TIRF/FRAP experiments

| Myo1c constructa | kslow (s−1)b | Rangec |

|---|---|---|

| GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3 (18) | 0.060 ± 0.037 | 0.013–0.15 |

| GFP-myo1c (10) | 0.050 ± 0.028 | 0.017–0.096 |

| GFP-K892A (4) | >1 s−1 | >1 s−1 |

| GFP-R903A (7) | >1 s−1 | >1 s−1 |

| GFP-myo1c-K892A (7) | >1 s−1 | >1 s−1 |

| GFP-myo1c-R903A (9) | >1 s−1 | >1 s−1 |

| GFP only (4) | >1 s−1 | >1 s−1 |

| GFP-myo1c-tailIQ2–3 (11) | 0.049 ± 0.028 | 0.018–0.087 |

| GFP-myo1c-tailIQ3 (16) | 0.050 ± 0.021 | 0.019–0.089 |

| GFP-myo1c-tailIQ0 (15) | 0.041 ± 0.012 | 0.012–0.094 |

a Number of FRAP transients is reported in the parentheses.

b Values of kslow were determined from fitting the data to the sum of two exponential transients. Values of kfast determined from the fits are as fast as the time resolution of the acquisitions and are not reported. Errors are SDs.

c Minimum and maximum values for the experimental set of kslow values.

The fluorescence after photobleaching of GFP-K892A and GFP-R903A almost completely recovered within the first acquisition point at a rate >1 s−1 (Figure 3 and Table 2), similar to control cells expressing GFP alone (our unpublished data). No slow phase was detected, suggesting that the mutants do not bind tightly to the membrane, which is consistent with the in vitro binding data (Figure 2 and Table 1).

Point Mutations in the Putative PH Domain Affect Myo1c Localization

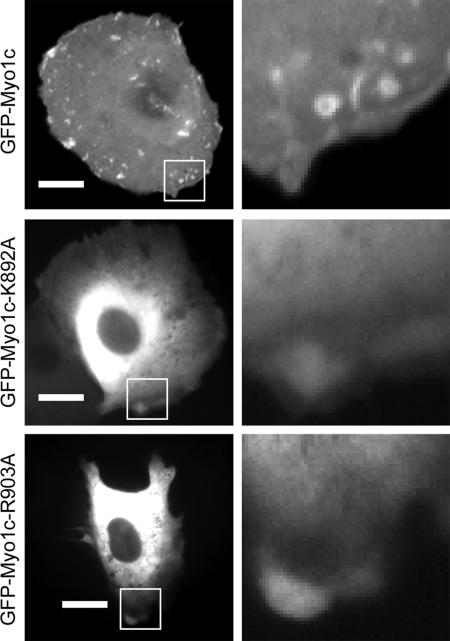

A full-length myo1c construct with GFP at the N terminus (GFP-myo1c) localizes to the cell membrane and is concentrated in regions of membrane ruffling and retraction (Figure 4and Supplemental Movie 3), as reported previously for endogenously expressed myo1c in NRK (Ruppert et al., 1995) and GFP-myo1c in NIH3T3 cells (Bose et al., 2004). Full-length GFP-myo1c constructs that contain the K892A (GFP-myo1c-K892A) and R903A (GFP-myo1c-K903A) mutations are localized to the cytoplasm with no concentration in the dynamic cell margins (Figure 4 and Supplemental Movies 4 and 5), suggesting the mutant constructs do not bind to the plasma membrane.

Figure 4.

Epifluorescence micrographs of live NRK cells expressing GFP-myo1c (top), GFP-myo1c-K892A (middle), and GFP-myo1c-R903A (bottom). The boxes outline the expanded regions shown in the right column. Note the localization of GFP-myo1c within the membrane ruffles and macropinocytic regions in the cell expressing the wild-type protein but not in the mutants. Time-lapse movies of these cells are available in the Supplemental Materials. Bars, 15 μm.

The fluorescence of GFP-myo1c after photobleaching in TIRF/FRAP experiments recovered in two phases, with kinetics nearly identical to GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3 (Table 2), indicating that the actin binding domain does not contribute significantly to the lifetime of plasma membrane attachment of the overexpressed protein. The fluorescence after photobleaching of GFP-myo1c-K892A and GFP-myo1c-K903A almost completely recovered within the first acquisition point at a rate of >1 s−1, confirming that the mutant full-length proteins do not bind tightly to the membrane. Therefore, we conclude that myo1c binds to membranes in vitro and in vivo via a region in the tail domain that is structurally homologous to the phosphoinositide binding site in PH domains.

Specificity of Myo1c for Inositol Phosphates

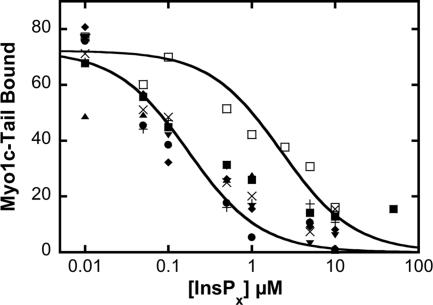

We have shown previously that myo1c binds the soluble phosphoinositide headgroup of PIP2, Ins(1,4,5)P3, with high affinity (Hokanson and Ostap, 2006). To determine whether the myo1c-tail is able to bind other soluble phosphoinositides, we measured the ability of Ins(3)P1, Ins(1,3,4)P3, Ins(1,2,6)P3, Ins(1,3,4,5)P4, Ins(1,2,5,6)P4, Ins(1,3,4,6)P4, Ins(1,2,3,5,6)P5, and InsP6 to compete with LUVs containing 2% PIP2 for binding myo1c-tailIQ1-3 (Figure 5 and Table 3). We found that the myo1c-tailIQ1-3 was displaced from LUVs with increasing concentrations of Ins(1,3,4)P3, Ins(1,2,6)P3, Ins(1,3,4,5)P4, Ins(1,2,5,6)P4, Ins(1,3,4,6)P4, Ins(1,2,3,5,6)P5, and InsP6. Ins(3)P1 did not displace myo1c-tailIQ1-3 at concentrations up to 100 μM (Table 3), and myo1c-tailIQ1-3 binds to Ins(1,2,6)P3 approximately fivefold more weakly than to Ins(1,4,5)P3 (Figure 5 and Table 3). These results suggest that myo1c has some phosphoinositide binding specificity for phosphates at the 4- and 5-positions of the inositol ring.

Figure 5.

Binding of 40–100 nM myo1c-tail to 60 μM LUVs containing 2% PIP2 in the presence of 0–50 μM Ins(1,4,5)P3 (■), Ins(1,3,4)P3 (▴), Ins(1,2,6)P3 (□), Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 (●), Ins(1,2,5,6)P4 (▴), Ins(1,3,4,6)P4 (×), Ins(1,2,3,5,6)P5 (+), and InsP6 (♦) (n for each point = 4–14). Solid lines are fits to the Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 (●) and Ins(1,2,6)P3 (□) by using the competition binding equation (see Materials and Methods). Points at 0 μM InsPx are not shown owing to logarithmic scale. The effective dissociation constants obtained from the fits are listed in Table 4.

Table 3.

Effective dissociation constants for inositol phosphates binding to myo1c-taila

| Inositol phosphate | Kdb |

|---|---|

| Ins(3)P1 | >1 μM |

| Ins(1,4,5)P3 | 96 ± 32 nM |

| Ins(1,3,4)P3 | 61 ± 25 nM |

| Ins(1,2,6)P3 | 630 ± 130 nM |

| Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 | 33 ± 7.0 nM |

| Ins(1,2,5,6)P4 | 53 ± 23 nM |

| Ins(1,3,4,6)P4 | 67 ± 17 nM |

| Ins(1,2,3,5,6)P5 | 44 ± 14 nM |

| InsP6 | 48 ± 16 nM |

a 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, and 1 μM calmodulin.

b Effective dissociation constants were determined by competition assays as described in Materials and Methods. Errors are SEs of the fit.

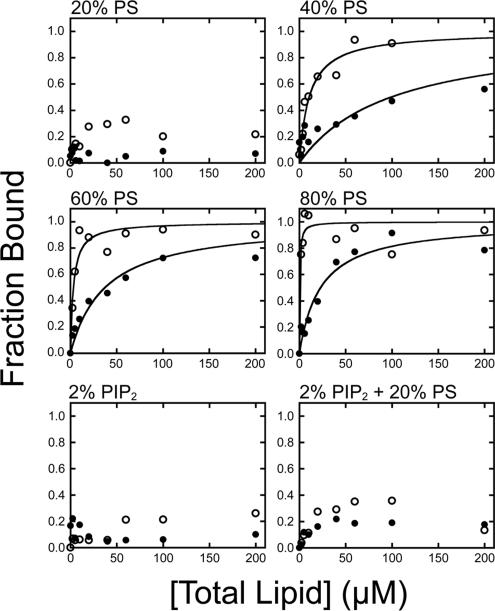

Contribution of the Regulatory Domain to Membrane Binding

It has been proposed that IQ motifs in the regulatory domains of some myosin-I isoforms contribute to membrane binding (Swanljung-Collins and Collins, 1992; Tang et al., 2002; Hirono et al., 2004). Although we demonstrated that this region is not responsible for binding to physiological levels of PIP2 (Hokanson and Ostap, 2006), it remains possible that the regulatory domain acts as a secondary membrane binding site. Therefore, we measured binding of a myo1c construct (myo1c-motorIQ1-3) that contains the motor and regulatory domain (but no tail) to LUVs composed of 20, 40, 60, and 80% PS, 2% PIP2, or both 20% PS and 2% PIP2 (Figure 6). In the absence of calcium, myo1c-motorIQ1-3 binds weakly to LUVs with ≤40% PS, whereas LUVs with ≥60% PS bind tightly (Table 4). In the presence of 10 μM free calcium, the affinity of myo1c-motorIQ1-3 for LUVs composed of 40–80% PS increased ∼10-fold, consistent with the proposal that positive charges in the IQ motif are revealed upon calcium-induced dissociation of calmodulin (Tang et al., 2002; Hirono et al., 2004).

Figure 6.

Lipid concentration dependence of 40 nM myo1c-motorIQ1-3 binding to LUVs composed of PC and 20% PS, 40% PS, 60% PS, 80% PS, 2% PIP2, and 20% PS + 2% PIP2 in the (●) absence and (○) presence of 10 μM free calcium. Data for 20% PS and 2% PIP2 have been reported previously (Hokanson and Ostap, 2006). Each point is the average of two to six measurements. The solid and dashed curves are the best fits of the data to hyperbolae. The Kefflipid of each data set is listed in Table 3.

Table 4.

Effective dissociation constants for myo1c-motorIQ1-3 binding to LUVsa

| LUV compositionb | Kefflipid (μM)c −Calcium | Kefflipid (μM)c +Calcium |

| 20% PS | >400 | >400 |

| 40% PS | 99 ± 24 | 11 ± 1.5 |

| 60% PS | 37 ± 5.6 | 3.2 ± 0.83 |

| 80% PS | 23 ± 3.3 | 0.42 ± 0.27 |

| 2% PIP2 | >400 | >400 |

| 2% PIP2 + 20% PS | >400 | >400 |

a 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, and 1 μM calmodulin.

b Mole percentages PS and PIP2 are reported with the remaining lipid composed of PC.

c Effective dissociation constants expressed in terms of total phospholipid. Errors are SEs of the fit.

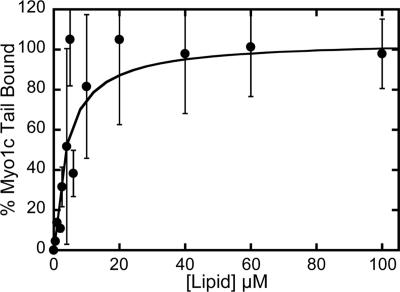

Biological membranes are composed of <40% PS, so it unlikely that binding to high PS concentrations is physiologically relevant. It is possible that high levels of free calcium induce PS to cluster and form microdomains that would be more favorable for the highly cationic IQ motifs to bind. However, it is more likely that low concentrations of PS contribute to the binding energy when myo1c is attached to the membrane via phosphoinositides. We therefore measured the binding of myo1c-tailIQ1-3 to LUVs composed of 2% PIP2 and 20% PS (Figure 7) and found the affinity to be approximately fivefold tighter (Kefflipid = 4.0 ± 1.5 μM) than to LUVs composed of 2% PIP2 alone (Kefflipid = 23 ± 5 μM; Table 1).

Figure 7.

Lipid concentration dependence of 40 nM myo1c-tailIQ1-3 binding to LUVs composed of 78% PC, 20% PS, and 2% PIP2. The solid line is the best fit of the data to a hyperbola (Kefflipid = 4.0 ± 1.5. Error bars represent the SD of each measurement (n = 6).

To test whether the IQ motifs in the regulatory domain are necessary for membrane binding in live NRK cells, we performed TIRF/FRAP microscopy of GFP-myo1c-tailIQ2–3, GFP-myo1c-tailIQ3, and GFP-myo1c-tailIQ0. The fluorescence after photobleaching of these constructs recovered in two phases, as seen with GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3 (Figure 3). The fast phases recovered within the time resolution of the experiment (>1 s−1), and the slow phases recovered with average rates between 0.041–0.049 s−1 (Table 2), which are not significantly different from kslow determined for GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3. Therefore, the regulatory domain is not necessary for membrane association in vivo; however, this finding does not rule out a role for the regulatory domain in targeting the motor to specific subcellular regions (Cyr et al., 2002; see Discussion).

DISCUSSION

Identification of the Phosphoinositide Binding Site

In this study, we identify the phosphoinositide binding site in the tail of myo1c, and we identify key residues essential for membrane binding. Based on structural, sequence homology, and biochemical analyses, we propose that this phosphoinositide binding region is a previously unidentified PH domain. The sequence homology of myo1c to PH domains is weak, yet structural analysis by using the Phyre server (www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/phyre/) allowed us to perform a sequence alignment and identify basic residues in the putative β1-loop-β2 region essential for phosphoinositide binding of certain PH domains (Figure 1; Cronin et al., 2004). Mutation of either of these residues to alanine annihilates in vitro binding to PIP2 (Figure 2) and in vivo binding to the plasma membrane, supporting the proposal that this region is a PH domain (Figure 3).

We performed ab initio structural prediction of residues P802-R1028 within the myo1c tail, resulting in a model structure that shows similarity to PH domains (see Materials and Methods). Although obviously speculative, the model is striking in its similarity to PH domains in the prediction of the structure of the β1-loop-β2 region as well as the β-sheet core structure (Figure 8 and Supplemental Materials). Specifically, when compared with the PH domain of Pdk1, we see that the structural alignment over the β1-loop-β2 region is very good (Figure 8), giving a protein backbone RMSD of 3.5 Å with a sequence identity of 61% (Figure 1). The computation failed to predict a C-terminal α-helical cap present in all PH domain structures (Lemmon and Ferguson, 2001), which may be a limitation of the computational method or may be due to actual differences in the structure itself.

Figure 8.

(A) Predicted structure for the myo1c tail region (orange) compared with the Pdk1 structure (green). (B) Detailed comparison of the β1-loop-β2 region of Pdk1 and the predicted structure of the Myo1c tail. Two of the residues in Pdk1 involved in coordinating the Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 molecule align with our two mutations at K892 and R903 (see sequence inset).

Although our modeling provides support for a PH domain in the myo1c tail, it is possible that this region is a novel PIP2 binding motif with sequence and structural elements similar to PH domains. Therefore, it is imperative we obtain the structure to better understand the structural diversity within the family of phosphoinositide binding proteins and the regulation of myosin-I isoforms.

Inositol Phosphate Specificity

Competition binding assays show that myo1c-tailIQ1-3 binds Ins(1,3,4)P3, Ins(1,4,5)P3, Ins(1,3,4,5)P4, Ins(1,2,5,6)P4, Ins(1,3,4,6)P4, Ins(1,2,3,5,6)P5, and InsP6 with similar tight affinities (Figure 5 and Table 3), indicating phosphoinositide binding is relatively promiscuous. These affinities are similar to those of PH domains specific for inositol phosphate Ins(1,4,5)P3, including phospholipase C (PLC)δ, Kd = 0.21 μM (Lemmon et al., 1995), or for Ins(1,3,4,5)P4, including Burton's tyrosine kinase (Btk), Kd = 0.040 μM (Baraldi et al., 1999), and Pdk1, Kd = 0.014 μM (Komander et al., 2004).

Myo1c-tailIQ1-3 binds Ins(1,2,6)P3 with a weak affinity (Figure 5 and Table 3) and does not bind Ins(3)P1 detectably (Table 3). Therefore, the binding affinity is not based on the charge of the inositol phosphate alone, but it is dependent on the positions of the phosphates on the inositol ring. Our experiments suggest that phosphates at the 4- or 5-positions are required for tight binding, whereas phosphates at the other positions do not prevent binding.

The myo1c-tail should be able to bind lipids that have headgroups listed in Table 3, with PIP2 [Ins(1,4,5)P3 headgroup] and PIP3 [Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 headgroup] being the most prevalent in the membrane and the most relevant to the proposed functions of myo1c (Yin and Janmey, 2003). The cellular concentration of PIP2 is much higher than PIP3 in both unstimulated and stimulated cells (Insall and Weiner, 2001; Dormann et al., 2002). Thus, in the absence of other phosphoinositide binding proteins, we would expect myo1c to interact with PIP2 based on its higher concentration (McLaughlin and Murray, 2005). However, our in vitro biochemical experiments cannot take into account the presence of other cellular phosphoinositide binding proteins, so further cellular experiments are required to determine in vivo specificity and binding of myo1c.

The Regulatory Domain and Membrane Association

Sedimentation assays confirm that the regulatory domain of myo1c is capable of binding negatively charged phospholipid membranes in vitro in a calcium-dependent manner (Figure 6 and Table 4), as proposed for myo1a (Collins and Swanljung-Collins, 1992) and myo1c (Tang et al., 2002; Hirono et al., 2004). High-affinity membrane binding via the regulatory domain in the absence and presence of calcium requires the membrane composition to be >40% PS, which is not a physiological mole fraction. However, the affinity of the myo1c-tailIQ1-3 interaction increases approximately fivefold with the inclusion of 20% PS in LUVs that contain 2% PIP2, suggesting the possibility that the regulatory domain plays a secondary role in membrane attachment, with the primary association occurring via phosphoinositide tail interactions (Hokanson and Ostap, 2006).

Although the presence of calcium increases the in vitro membrane affinity for PS (Figure 6), previous experiments show that increased intracellular calcium concentrations result in dissociation of GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3 from the plasma membrane (Hokanson and Ostap, 2006). Additionally, TIRF/FRAP experiments reveal that the regulatory domain is not necessary for plasma membrane association in live cells (Table 2). Therefore, we conclude that the primary attachment to the membrane is not mediated by the regulatory domain.

We must emphasize that our TIRF/FRAP experiments are designed to detect membrane attachment only. The high expression levels of the GFP constructs and the short acquisition integration time prevent us from confidently examining subtle changes in subcellular localizations. Additionally, the motor domain is required for correct subcellular localization of myo1c (Ruppert et al., 1995; Tang and Ostap, 2001; Bahler and Rhoads, 2002), which our IQ-motif deletion constructs do not contain. Although we can rule out the requirement of the regulatory domain for plasma membrane attachment, further experiments are required to determine its role in myosin-I targeting (Cyr et al., 2002).

Phosphoinositide Binding by Other Myosin-I Isoforms

Alignment of myo1c with the other seven vertebrate myosin-I isoforms shows sequence conservation in the β1-loop-β2 motif region of the putative PH domain. The highest sequence similarity is among the short tail myosin-I isoforms (myo1a, myo1b, myo1c, and myo1d; Figure 1B). Thus, we propose that the short-tail isoforms will bind to phosphoinositides in a manner similar to myo1c. We have also found extended sequence similarities of this region to myosin-Is from other species including 61F and 31DF from Drosophila, hum-5 and hum-1 from Caenorhabditis elegans, and Myo3 and Myo5 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nevertheless, this region is not completely conserved, which leaves open the possibility that the different short-tail isoforms differ in their phosphoinositide affinity and specificity.

Long-tail myosin-I isoforms (myo1e and myo1f) contain only the N-terminal portion of the PH domain signature motif (Figure 1B). The sequences diverge from the signature motif in the putative loop region, but the sequences do contain several positive charges that may be positioned for phosphoinositide binding. Long-tail myosin-I isoforms have been shown to bind acidic phospholipids (Adams and Pollard, 1989; Miyata et al., 1989; Stoffler et al., 1995), so it is possible that differences in this region may result in differences in membrane binding properties.

Biological Relevance of PIP2 Binding

Phosphoinositides are concentrated in actin-rich structures where they regulate the activity of several cytoskeletal proteins, including activators of the Arp2/3 complex, actin severing and capping proteins, and actin monomer binding proteins (Insall and Weiner, 2001; Yin and Janmey, 2003). Myosin-I isoforms are also enriched in these regions. One role of phosphoinositides in actin-rich structures may simply be to serve as spatially regulated membrane anchors for myosin-I isoforms, allowing the recruitment of myosin-I to function in endocytosis (Novak et al., 1995; Jung et al., 1996; Swanson et al., 1999; Ostap et al., 2003), secretion (Bose et al., 2002), and membrane retraction. However, myosin-I isoforms may also use their barbed-end–directed motor activity to keep the fast-growing ends of the actin filament oriented toward the membrane and phosphoinositide regulators of the cytoskeleton (Jung et al., 2001).

Myosin-I isoforms may also link phosphoinositides to other regulatory proteins. For example, β-catenin and dynamin have been shown to bind myosin-I in Drosophila, where they play a role in the control of left-right asymmetry during development (Hozumi et al., 2006; Speder et al., 2006). However, the function of myosin-I in these processes is not understood, and it is not known whether the motor and phosphoinositide binding activity of myosin-I drives the localization of these proteins, or whether myosin-I is targeted to specific regions by binding to these proteins. PHR1, a recently identified integral membrane protein present in the sensory cells of the inner ear, binds myo1c and may link it to stereocilia membranes (Etournay et al., 2005). Myo1c is the likely motor that drives mechanical adaptation in hair cells (Gillespie and Cyr, 2004), and depletion of PIP2 inhibits this adaptation (Hirono et al., 2004). Therefore, it is likely that PHR1 and PIP2 act to link myo1c to the adaptation complex (Hirono et al., 2004; Etournay et al., 2005). It is interesting to speculate that control of the levels of membrane phosphoinositides regulates the assembly of this motor complex.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Mark Lemmon for suggesting structural homology analyses and for helping to design point mutants. We also thank Dr. Kate Ferguson for helpful discussions, Dr. Joseph Forkey for assistance in setting up the TIRF microscope, and Dr. Nanyun Tang for the GFP-myo1c expression constructs. E.M.O. was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant GM-57247 and an American Heart Association Established Investigator grant. D.S. was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM-067246.

Abbreviations used:

- GFP

green fluorescence protein

- GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3

GFP-tagged myo1c (residues 690-1028)

- GFP-myo1c-tailIQ2–3

GFP-tagged myo1c (residues 721-1028)

- GFP-myo1c-tailIQ3

GFP-tagged myo1c (residues 744-1028)

- GFP-myo1c-tailIQ0

GFP-tagged myo1c (residues 768-1028)

- GFP-K892A and GFP-R903A

point mutations in GFP-myo1c-tailIQ1-3

- GFP-myo1c-K892A and GFP-myo1c-K903A

point mutations in GFP-myo1c

- Ins(1,2,6)P3

d-myo-inositol-1,2,6-trisphosphate

- Ins(1,3,4)P3

d-myo-inositol-1,3,4-trisphosphate

- Ins(1,4,5)P3

d-myo-inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate

- Ins(1,3,4,5)P4

d-myo-inositol-1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate

- Ins(1,2,5,6)P4

d-myo-inositol-1,2,5,6-tetrakisphosphate

- Ins(1,3,4,6)P4

d-myo-inositol-1,3,4,6-tetrakisphosphate

- Ins(1,2,3,5,6)P5

d-myo-inositol-1,2,3,5,6-pentakisphosphate

- Ins(3)P1

d-myo-inositol-3-monophosphate

- InsP6

d-myo-inositol hexakisphosphate

- LUV

large unilamellar vesicle

- myo1c-tailIQ1-3

myo1c (residues 690-1028)

- myo1c-motorIQ1-3

myo1c (residues 1–767)

- PH

pleckstrin homology

- PIP2

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PS

phosphatidylserine.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E06-05-0449) on September 13, 2006.

REFERENCES

- Adams R. J., Pollard T. D. Binding of myosin I to membrane lipids. Nature. 1989;340:565–568. doi: 10.1038/340565a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod D. Total internal reflection microscopy in cell biology. Traffic. 2001;2:764–774. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.21104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahler M., Rhoads A. Calmodulin signaling via the IQ motif. FEBS Lett. 2002;513:107–113. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraldi E., Carugo K. D., Hyvonen M., Surdo P. L., Riley A. M., Potter B. V., O'Brien R., Ladbury J. E., Saraste M. Structure of the PH domain from Bruton's tyrosine kinase in complex with inositol 1,3,4,5–tetrakisphosphate. Structure. 1999;7:449–460. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A., et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D138–D141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg J. S., Powell B. C., Cheney R. E. A millennial myosin census. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:780–794. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.4.780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonneau R., Strauss C. E., Rohl C. A., Chivian D., Bradley P., Malmstrom L., Robertson T., Baker D. De novo prediction of three-dimensional structures for major protein families. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;322:65–78. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00698-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose A., Guilherme A., Robida S. I., Nicoloro S. M., Zhou Q. L., Jiang Z. Y., Pomerleau D. P., Czech M. P. Glucose transporter recycling in response to insulin is facilitated by myosin Myo1c. Nature. 2002;420:821–824. doi: 10.1038/nature01246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose A., Robida S., Furcinitti P. S., Chawla A., Fogarty K., Corvera S., Czech M. P. Unconventional myosin Myo1c promotes membrane fusion in a regulated exocytic pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:5447–5458. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5447-5458.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins J. H., Swanljung-Collins H. Calcium regulation of myosin I-a motor for membrane movement. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1992;321:159–163. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-3448-8_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coluccio L. M. Myosin I. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:C347–C359. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.2.C347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin T. C., DiNitto J. P., Czech M. P., Lambright D. G. Structural determinants of phosphoinositide selectivity in splice variants of Grp1 family PH domains. EMBO J. 2004;23:3711–3720. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyr J. L., Dumont R. A., Gillespie P. G. Myosin-1c interacts with hair-cell receptors through its calmodulin-binding IQ domains. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:2487–2495. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02487.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dormann D., Weijer G., Parent C. A., Devreotes P. N., Weijer C. J. Visualizing PI3 kinase-mediated cell-cell signaling during Dictyostelium development. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:1178–1188. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00950-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etournay R., et al. PHR1, an integral membrane protein of the inner ear sensory cells, directly interacts with myosin 1c and myosin VIIa. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:2891–2899. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie P. G., Cyr J. L. Myosin-1c, the hair cell's adaptation motor. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2004;66:521–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.112842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden S. M., Wolenski J. S., Mooseker M. S. Binding of brush border myosin I to phospholipid vesicles. J. Cell Biol. 1990;111:443–451. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.2.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirono M., Denis C. S., Richardson G. P., Gillespie P. G. Hair cells require phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate for mechanical transduction and adaptation. Neuron. 2004;44:309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokanson D. E., Ostap E. M. Myo1c binds tightly and specifically to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:3118–3123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505685103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt J. R., Gillespie S. K., Provance D. W., Shah K., Shokat K. M., Corey D. P., Mercer J. A., Gillespie P. G. A chemical-genetic strategy implicates myosin-1c in adaptation by hair cells. Cell. 2002;108:371–381. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00629-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hozumi S., et al. An unconventional myosin in Drosophila reverses the default handedness in visceral organs. Nature. 2006;440:798–802. doi: 10.1038/nature04625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S., Lifshitz L., Patki-Kamath V., Tuft R., Fogarty K., Czech M. P. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate-rich plasma membrane patches organize active zones of endocytosis and ruffling in cultured adipocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:9102–9123. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.9102-9123.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insall R. H., Weiner O. D. PIP3, PIP2, and cell movement–similar messages, different meanings? Dev. Cell. 2001;1:743–747. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00086-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isakoff S. J., Cardozo T., Andreev J., Li Z., Ferguson K. M., Abagyan R., Lemmon M. A., Aronheim A., Skolnik E. Y. Identification and analysis of PH domain-containing targets of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase using a novel in vivo assay in yeast. EMBO J. 1998;17:5374–5387. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson M. P., Pincus D. L., Rapp C. S., Day T. J., Honig B., Shaw D. E., Friesner R. A. A hierarchical approach to all-atom protein loop prediction. Proteins. 2004;55:351–367. doi: 10.1002/prot.10613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung G., Remmert K., Wu X., Volosky J. M., Hammer J. A., 3rd The Dictyostelium CARMIL protein links capping protein and the Arp2/3 complex to type I myosins through their SH3 domains. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:1479–1497. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.7.1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung G., Wu X., Hammer J. A., 3rd Dictyostelium mutants lacking multiple classic myosin I isoforms reveal combinations of shared and distinct functions. J. Cell Biol. 1996;133:305–323. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.2.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley L. A., MacCallum R. M., Sternberg M. J. Enhanced genome annotation using structural profiles in the program 3D-PSSM. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;299:499–520. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komander D., Fairservice A., Deak M., Kular G. S., Prescott A. R., Peter Downes C., Safrany S. T., Alessi D. R., van Aalten D. M. Structural insights into the regulation of PDK1 by phosphoinositides and inositol phosphates. EMBO J. 2004;23:3918–3928. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon M. A., Ferguson K. M. Molecular determinants in pleckstrin homology domains that allow specific recognition of phosphoinositides. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2001;29:377–384. doi: 10.1042/bst0290377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon M. A., Ferguson K. M., O'Brien R., Sigler P. B., Schlessinger J. Specific and high-affinity binding of inositol phosphates to an isolated pleckstrin homology domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:10472–10476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl E., Hess B., van der Spoel D. GROMACS 3.0, a package for molecular simulation and trajectory analysis. J. Mol. Mod. 2001;7:306–317. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin S., Murray D. Plasma membrane phosphoinositide organization by protein electrostatics. Nature. 2005;438:605–611. doi: 10.1038/nature04398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin S., Wang J., Gambhir A., Murray D. PIP(2) and proteins: interactions, organization, and information flow. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2002;31:151–175. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.082901.134259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata H., Bowers B., Korn E. D. Plasma membrane association of Acanthamoeba myosin I. J. Cell Biol. 1989;109:1519–1528. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.4.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak K. D., Peterson M. D., Reedy M. C., Titus M. A. Dictyostelium myosin I double mutants exhibit conditional defects in pinocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 1995;131:1205–1221. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.5.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostap E. M., Maupin P., Doberstein S. K., Baines I. C., Korn E. D., Pollard T. D. Dynamic localization of myosin-I to endocytic structures in Acanthamoeba. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 2003;54:29–40. doi: 10.1002/cm.10081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papayannopoulos V., Co C., Prehoda K. E., Snapper S., Taunton J., Lim W. A. A polybasic motif allows N-WASP to act as a sensor of PIP(2) density. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peitzsch R. M., McLaughlin S. Binding of acylated peptides and fatty acids to phospholipid vesicles: pertinence to myristoylated proteins. Biochemistry. 1993;32:10436–10443. doi: 10.1021/bi00090a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putkey J. A., Slaughter G. R., Means A. R. Bacterial expression and characterization of proteins derived from the chicken calmodulin cDNA and a calmodulin processed gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:4704–4712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruppert C., Godel J., Muller R. T., Kroschewski R., Reinhard J., Bahler M. Localization of the rat myosin I molecules myr 1 and myr 2 and in vivo targeting of their tail domains. J. Cell Sci. 1995;108:3775–3786. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.12.3775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokac A. M., Bement W. M. Regulation and expression of metazoan unconventional myosins. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2000;200:197–304. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(00)00005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speder P., Adam G., Noselli S. Type ID unconventional myosin controls left-right asymmetry in Drosophila. Nature. 2006;440:803–807. doi: 10.1038/nature04623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoffler H. E., Ruppert C., Reinhard J., Bahler M. A novel mammalian myosin I from rat with an SH3 domain localizes to Con A-inducible, F-actin-rich structures at cell-cell contacts. J. Cell Biol. 1995;129:819–830. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.3.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanljung-Collins H., Collins J. H. Phosphorylation of brush border myosin I by protein kinase C is regulated by Ca(2+)-stimulated binding of myosin I to phosphatidylserine concerted with calmodulin dissociation. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:3445–3454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson J. A., Johnson M. T., Beningo K., Post P., Mooseker M., Araki N. A contractile activity that closes phagosomes in macrophages. J. Cell Sci. 1999;112:307–316. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang N., Lin T., Ostap E. M. Dynamics of myo1c (myosin-ibeta) lipid binding and dissociation. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:42763–42768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206388200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang N., Ostap E. M. Motor domain-dependent localization of myo1b (myr-1) Curr. Biol. 2001;11:1131–1135. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00320-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyska M. J., Mackey A. T., Huang J. D., Copeland N. G., Jenkins N. A., Mooseker M. S. Myosin-1a is critical for normal brush border structure and composition. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:2443–2457. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-12-1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyska M. J., Mooseker M. S. MYO1A (brush border myosin I) dynamics in the brush border of LLC-PK1-CL4 cells. Biophys. J. 2002;82:1869–1883. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75537-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H. L., Janmey P. A. Phosphoinositide regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003;65:761–789. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T., Beckingham K., Ikebe M. High affinity Ca2+ binding sites of calmodulin are critical for the regulation of myosin Ibeta motor function. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:20481–20486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.