Abstract

PCR-based subtractive hybridization was used to isolate sequences from Erwinia amylovora strain Ea110, which is pathogenic on apples and pears, that were not present in three closely related strains with differing host specificities: E. amylovora MR1, which is pathogenic only on Rubus spp.; Erwinia pyrifoliae Ep1/96, the causal agent of shoot blight of Asian pears; and Erwinia sp. strain Ejp556, the causal agent of bacterial shoot blight of pear in Japan. In total, six subtractive libraries were constructed and analyzed. Recovered sequences included type III secretion components, hypothetical membrane proteins, and ATP-binding proteins. In addition, we identified an Ea110-specific sequence with homology to a type III secretion apparatus component of the insect endosymbiont Sodalis glossinidius, as well as an Ep1/96-specific sequence with homology to the Yersinia pestis effector protein tyrosine phosphatase YopH.

Erwinia amylovora is the causal agent of fire blight disease of apple, pear, and many other rosaceous species. Interestingly, strains of E. amylovora that infect raspberry and other brambles (Rubus spp.) are unable to infect apple and pear (2, 9). The Rubus-infecting strains of E. amylovora are closely related to the apple- and pear-infecting strains, as evidenced by similar amplified fragment length polymorphism and PCR fingerprints, species-level total DNA-DNA homology, and nearly identical sequences in pathogenicity and virulence genes (7, 11, 16-18). Recently, other blight-causing Erwinia sp. strains with restricted host ranges have been described; Erwinia pyrifoliae was identified as the cause of Asian pear blight (12), and Erwinia sp. strains isolated in Japan cause bacterial shoot blight of pears (13). The Asian strains produced no symptoms when inoculated on apple seedlings (13, 14). Comparisons of chromosomal and plasmid sequences and amplified fragment length polymorphism profiles have indicated that E. pyrifoliae is genetically distinct from but closely related to E. amylovora and that the Erwinia sp. strains from Japan are more closely related to E. pyrifoliae than to E. amylovora (12-14, 16, 17). Despite their phenotypic and genetic similarities, the basis for differences in host specificity between these Erwinia strains remains unknown.

Suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH) is a PCR-based method that has been widely used to identify differences between prokaryotic genomes with differing phenotypes, including those of pathogenic and nonpathogenic strains of the same species (19), and between different, closely related species (3). SSH has also been used to analyze genetic differences between plant-pathogenic strains varying in host specificity (8, 28).

Our objective in this study was to identify genomic differences among plant-pathogenic Erwinia strains. We used SSH to generate six subtractive libraries to compare the genomes of fruit tree-infecting E. amylovora strains with those of E. pyrifoliae, a Japanese Erwinia sp. strain, and a Rubus-infecting strain of E. amylovora. These experiments resulted in the identification of strain-specific sequences including genes encoding a putative type III secretion system (T3SS) effector, a T3SS apparatus component, and several putative membrane proteins.

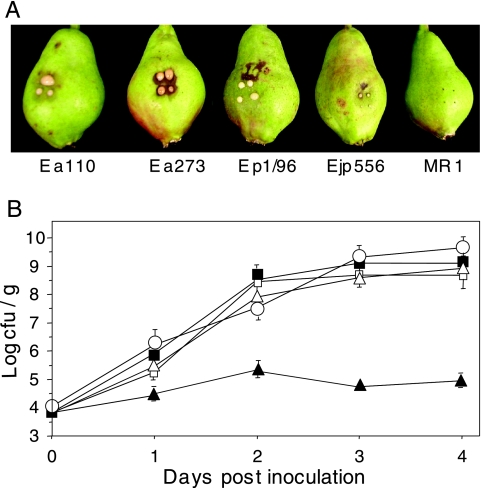

Pathogenicity of Erwinia strains on immature pears.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Immature pears were wounded and inoculated with 6 × 103 cells of E. amylovora strains Ea110, Ea273, and MR1; Erwinia sp. strain Ejp556; and E. pyrifoliae Ep1/96. After incubation for 3 days, pears infected with strains Ea110, Ea273, and Ep1/96 displayed symptoms typical of fire blight infection, including extensive water soaking and necrosis accompanied by the production of bacterial ooze (Fig. 1A). Pears infected with Ejp556 displayed these same symptoms to a reduced extent, and pears inoculated with MR1 showed no signs of infection (Fig. 1A). Cell counts from inoculated pears revealed that strains inciting disease symptoms on pears increased 104- to 105-fold over the 4-day period, while populations of MR1 remained relatively constant (Fig. 1B). In contrast to its reaction in immature pear fruit, E. amylovora MR1 is a virulent pathogen on raspberry and is capable of inciting shoot blight symptoms on raspberry plants (G. C. McGhee and A. L. Jones, unpublished observations, and data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Erwinia strains used in this study and their indigenous plasmid content

| Species and strain | Plasmid(s) or relevant characteristic | Host(s) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erwinia amylovora | |||

| Ea110 | pEA29 | Apple, pear | 20 |

| Ea110− | Cured of pEA29 | Apple, pear | 29 |

| Ea273 | pEA29, 71.5-kb plasmid | Apple, pear | 24 |

| MR1 | pEA29 | Rubus sp. | 18 |

| Ea321 | pEA29 | Crataegus | 24 |

| Erwinia pyrifoliae | |||

| Ep1/96 | pEP36 and 3 small plasmids | Asian pear | 12, 16, 17 |

| Ep4/97 | pEP36 | Asian pear | 12 |

| Erwiniasp. | |||

| Ejp556 | pEJ30 | Asian pear | 13, 16 |

| Ejp557 | pEJ30 | Asian pear | 13 |

FIG. 1.

(A) Symptom expression in immature pear fruit following inoculation with Erwinia amylovora Ea110, Ea273, and MR1; E. pyrifoliae Ep1/96; and Erwinia sp. strain Ejp556. Each fruit was inoculated in four places. (B) Growth of E. amylovora Ea110 (▪), Ea273 (□), and MR1 (▴); E. pyrifoliae Ep1/96 (▵); and Erwinia sp. strain EJP556 (○) during infection of immature pears. The growth of bacterial strains was monitored at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 days after inoculation. Data points represent the means of three replicates ± standard errors. Similar results were obtained in two additional independent experiments.

SSH and isolation of E. amylovora-specific sequences.

SSH is used to enrich for PCR products unique to a tester genome, with amplification of sequences from a driver genome suppressed. Six subtractive libraries were made: three used E. amylovora Ea110− as the tester and E. pyrifoliae Ep1/96, Erwinia sp. strain Ejp556, or E. amylovora MR1 as the driver, and three were created with either Ep1/96, Ejp556, or MR1 as the tester and Ea273 as the driver (Table 2). E. amylovora Ea273 was a strain of choice because a genome sequencing project of this strain is under way (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/E_amylovora/), and so this strain was used as a driver in subtractions enriching for restricted-host-range strains. However, Ea273 also contains a 71.5-kb indigenous plasmid previously thought to be similar to a plasmid in E. amylovora Ea322 (24). The plasmid from E. amylovora Ea322 has no known involvement in virulence and no known counterpart in Ea110, Ep1/96, Ejp556, or MR1 (17). To avoid the creation of subtractive libraries enriched with sequences from this plasmid or the ubiquitous plasmid pEA29, a plasmid-cured strain of E. amylovora Ea110 designated Ea110− was used as the tester in SSH experiments. All Ea110−-specific sequences were later confirmed to be present in the Ea273 genome.

TABLE 2.

Libraries generated by suppression subtractive hybridization in this study

| Subtractive library | No. of unique sequences (no. of sequences with significant BlastX match) |

|---|---|

| Ea110− (apple) − MR1 (Rubus spp.) | 10 (7) |

| Ea110− (apple) − Ep1/96 (pear) | 11 (9) |

| Ea110− (apple) − Ejp556 (pear) | 10 (7) |

| Ep1/96 (pear) − Ea273 (apple) | 8 (5) |

| Ejp556 (pear) − Ea273 (apple) | 14 (9) |

| MR1 (Rubus spp.) − Ea273 (apple) | 0 |

SSH was performed using the PCR-Select bacterial genome subtraction kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions, except that the primary PCR was increased to 28 cycles. PCR products were ligated into the pGEM T-Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI) and transformed into chemically competent cells of Escherichia coli DH5α. For the three subtractions that used E. amylovora Ea110− as the tester, inserts from 96 randomly selected clones were amplified by PCR using primers specific to the oligonucleotide adapters, denatured for 10 min at 95°C, and spotted onto duplicate Immobilon-P nylon membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Tester and driver genomic DNAs were labeled with digoxigenin (DIG) by random priming using the DIG DNA labeling kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Duplicate membranes were hybridized overnight to tester and driver probes at 63°C as described in the DIG application manual (Roche). PCR products hybridizing more strongly to tester DNA were purified, spotted onto new membranes, and reprobed. Products hybridizing only to tester DNA were sequenced at the Michigan State University Genomics Technology Support Facility, and these sequences were then tested for homogeneity to other genetic elements by using BlastX and BlastN (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/).

The subtraction Ea110− − MR1 yielded 10 unique Ea110−-specific sequences, including EM4, a sequence sharing greater than 30% amino acid identity with exopolysaccharide (EPS) acetyltransferases from Burkholderia and Xanthomonas spp. and an ExoZ homolog from Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. Although the functional role of EPS acetylation in plant pathogens has not been studied, ExoZ is thought to reduce EPS susceptibility to cleavage in Rhizobium meliloti (27). In addition, three SSH clones contained a total of five putative genes that were similar to genes from the insect endosymbiont Photorhabdus luminescens (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Sequence analysis of inserts specific to E. amylovora Ea110− but not to E. amylovora MR1, E. pyrifoliae Ep1/96, or Erwinia sp. strain Ejp556

| Subtractive library | SSH clone | Organism, similar protein | Predicted function | BlastX E value | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ea110− − MR1 | EM1a,b | Photorhabdus luminescens, Plu3117 | Hypothetical protein | 2 E−17 | CAE15491 |

| Photorhabdus luminescens, Plu3116 | Hypothetical protein | 9 E−17 | CAE15490 | ||

| EM2a | Photorhabdus luminescens, Plu4876 | Hypothetical protein | 2 E−41 | CAE17248 | |

| Photorhabdus luminescens, Plu4875 | Hypothetical protein | 1 E−5 | CAE17247 | ||

| EM3a | Photorhabdus luminescens, Plu1815 | DNA-damage inducible protein | 5 E−7 | CAE14108 | |

| Shewanella denitrificans, Sden_3233 | Phage integrase | 2 E−36 | ZP_00583430 | ||

| EM4 | Burkholderia xenovorans,ExoZ | Exopolysaccharide biosynthesis | 4 E−43 | YP_553663 | |

| EM5c | Escherichia coli, EcolB7_01003583 | Predicted ATPase | 9 E−58 | ZP_00714762 | |

| EM6 | Oceanobactersp., Red65_14712 | Hypothetical protein | 4 E−28 | ZP_01306318 | |

| EM7 | Pseudomonas putida, Pp2746 | Hypothetical protein | 9 E−61 | NP_744890 | |

| Ea110− − Ep1/96 | EP1 | E. amylovora, AmsF | Exopolysaccharide biosynthesis | 5 E−3 | CAA54887 |

| EP2b | Sodalis glossinidius, YsaQ | T3SS invasion protein | 2 E−23 | AAS66845 | |

| EP3b | Pseudomonas putida, Pp5253 | Putative arylesterase | 7 E−28 | NP_747354 | |

| EP4 | Salmonella enterica, CysQ | Ammonium transport | 4 E−47 | NP_458840 | |

| EP5b | Pseudomonas syringae, Psyr_4778 | Hypothetical protein | 8 E−13 | YP_237843 | |

| EP6 | Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, MglA | Galactoside ABC transporter | 7 E−127 | AAC44149 | |

| EP7 | Klebsiella pneumoniae, OrfX | Membrane dipeptidase | 3 E−46 | CAA41578 | |

| EP8 | Salmonella enterica, Sc0250 | Hypothetical protein | 9 E−26 | YP_215237 | |

| EP9a | Escherichia coli, C3433 | Hypothetical protein | 2 E−6 | ZP_00727249 | |

| Photorhabdus luminescens, FtsI | FtsI precursor | 2 E−5 | CAE16033 | ||

| Ea110− − Ejp556 | EJ1 | Escherichia coli, RfaK | Lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis | 9 E−6 | AAA24523 |

| EJ2 | Erwinia amylovora, OrfL | Unknown, chitin-binding domain | 1 E−87 | AAX39449 | |

| EJ3c | Escherichia coli, EcolB7_01003583 | Predicted ATPase | 9 E−58 | ZP_00714762 | |

| EJ4 | Escherichia coli, EcolB7_01003586 | Hypothetical protein | 1 E−96 | ZP_00714765 | |

| EJ5 | Escherichia coli, Orf5 | Hypothetical protein | 2 E−15 | CAA11511 | |

| EJ6 | Salmonella enterica, YidR | Putative ATP-binding protein | 7 E−18 | AAV79455 | |

| EJ7a | E. amylovora, Orf106 | Hypothetical protein | 1 E−37 | CAH41996 | |

| E. amylovora, Orf81 | Hypothetical protein | 7 E−33 | CAH41995 |

Clones EM1, EM2, EM3, EP9, and EJ6 contained sequences from two genes.

The sequences in clones EM1, EP2, EP3, and EP5 were each found in more than one clone.

Clones EM5 and EJ3 contained identical insert sequences.

The subtraction Ea110− − Ep1/96 yielded nine nonredundant clones with significant BlastX hits, including a sequence from clone EP1 that was similar to amsF from E. amylovora, a gene involved in synthesis of the EPS and essential pathogenicity factor amylovoran (Table 3) (4). A sequence matching EP1 was obtained from the E. amylovora sequence database website (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/E_amylovora/), revealing a 1.8-kb open reading frame (ORF) with 37% amino acid similarity to AmsF. However, this ORF does not appear to be flanked by other ams gene homologs and thus is most likely in a different genomic location than the ams operon. Another sequence, EP2, shared 31% amino acid identity with the T3SS gene ysaQ from the insect endosymbiont Sodalis glossinidius (Table 3). This T3SS is required for host cell invasion and host transfer of the endosymbiont (5). EP6 was 91% identical to 268 amino acids of the 506-amino-acid protein MglA, a highly conserved ABC transporter involved in galactose uptake in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (23).

The subtraction Ea110− − Ejp556 led to the identification of seven unique sequences with matches to known genes, including sequence EJ1, which shared 24% amino acid similarity with the E. coli protein RfaK, which is thought to be involved in modification of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) core to facilitate O-antigen attachment (Table 3) (15). LPS O-antigen biosynthetic genes have been found to differ significantly between the closely related Xanthomonas, Xylella, and Serratia marcescens genomes (22, 25, 28).

Isolation of sequences specific to Asian Erwinia strains.

For subtractions enriching for sequences specific to Asian Erwinia strains, clone inserts were sequenced at random prior to hybridization screening. Sequences were screened against the genome of the driver, Ea273, to screen for tester specificity and were confirmed by dot blot hybridization.

Of 48 clones sequenced from the subtraction Ejp556 − Ea273, 14 clones were tester specific, with 9 of these sharing significant homology with known sequences (Table 4). JE1 contained ejp19, a putative membrane ABC transporter previously identified in Ejp556 (16), and JE2, JE3, and JE4 also contained gene sequences with similarity to hypothetical transmembrane proteins. Previous work has reported that differences between Rubus strains and other isolates of E. amylovora include several membrane proteins and an ABC transporter (2).

TABLE 4.

Sequence analysis of SSH inserts specific to Erwinia sp. strain Ejp556 or E. pyrifoliae but not to E. amylovora Ea273

| Subtractive library | SSH Clone | Organism, similar protein | Predicted function | BlastX E value | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ejp556 − Ea273 | E1 | Erwinia sp. strain Ejp556, Ejp19 | ATP-binding ABC transporter | 6 E−40 | NP_857628 |

| JE2a | Thiomicrospira crunogena, Tcr_0083 | Hypothetical protein | 7 E−18 | ABB40679 | |

| JE3 | Escherichia coli, YbiO | Putative membrane transport protein | 4 E−19 | AAN79366 | |

| JE4 | Yersinia mollareti, Y mola_01003756 | Hypothetical protein | 7 E−47 | ZP_00823862 | |

| JE5 | Burkholderia fungorum, Bcep02003426 | Hypothetical chitin-binding protein | 1 E−15 | ZP_00281547 | |

| JE6 | Carnobacterium divergens, DvnA | Divergicin A precursor | 6 E−6 | AAZ29031 | |

| JE7 | Escherichia coli, C2473 | Transposase | 2 E−19 | AAN80932 | |

| Erwinia carotovora, Eca1054 | Integrase | 4 E−11 | YP_215278 | ||

| JE8 | Caenorhabditis elegans, K06A9.1c | Hypothetical protein | 1 E−5 | AAP82647 | |

| JE9 | Photorhabdus luminescens, Plu3156 | Hypothetical protein | 4 E−17 | CAE15530 | |

| Ep1/96 − Ea273 | PE1 | Thiomicrospira crunogena, Tcr_0083 | Hypothetical protein | 5 E−18 | ABB40679 |

| PE2 | Burkholderia sp., Bcep18194_c7625 | Putative conserved lipoprotein | 3 E−8 | ABB06669 | |

| PE3b | Yersinia pestis, YopH | Type III effector protein | 3 E−5 | AAC69768 | |

| PE4 | Escherichia coli, Tsr | Methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein | 8 E−16 | AAN83850 | |

| PE5b,c | Bordetella parapertussis, BPP0716 | Hypothetical protein | 2 E−50 | CAE40125 | |

| Novosphingobium aromaticivorans, Saro02002220 | Family 19 glycoside hydrolase | 3 E−24 | YP_498016 |

Clones JE2 and PE1 contained sequences from the same gene.

The sequences in PE3 and PE5 were found in more than one clone.

PE5 contained sequences from two genes.

In the subtraction Ep1/96 − Ea273, Ep1/96 plasmid DNA (300 ng) was added to the primary and secondary hybridizations of Ea273 genomic DNA and Ep1/96 genomic DNA. This plasmid DNA was added to hybridize with adapter-ligated tester plasmid DNA, reducing preferential amplification of the small plasmids specific to this strain (17). Nevertheless, over half of the tester-specific sequences resulting from this subtraction matched known sequences from these small plasmids (data not shown). Of the remaining eight tester-specific sequences, five unique sequences were identified with significant BlastX matches (Table 4). Sequence analysis of clone PE3 showed a predicted 48% amino acid similarity with the Yersinia pestis type III effector YopH, a tyrosine phosphatase that targets a variety of immune signaling pathways (26). Comparison of this sequence with the E. amylovora genomic database revealed a 1,587-nucleotide ORF with 57% nucleotide sequence similarity to the Ep1/96 putative YopH homolog and 33% similarity to YopH itself. Mutagenesis of these sequences in E. amylovora and E. pyrifoliae is under way to determine whether the YopH homologs have a role in virulence or host specificity.

Assay for sequences specific to MR1 but not Ea273.

SSH libraries were also constructed using Rubus-specific strain MR1 as the tester, but no MR1-specific sequences were found after screening 36 sequences from two independent subtractions. A previous SSH study of Xylella fastidiosa genomes failed to find tester-specific clones when the tester genome was slightly smaller than that of the driver (8). Similarly, the MR1 genome could be smaller than that of Ea273.

Distribution of isolated sequences among Erwinia strains.

Ea110−-specific sequence EP2 (Table 3), which was similar to YsaQ from S. glossinidius, was subjected to Blast analysis against the E. amylovora Ea273 genomic sequence (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/E_amylovora/). Further analysis of the Ea273 chromosomal sequence revealed two copies of a putative T3SS with high similarity to S. glossinidius symbiosis island SSR-1, which is required for Sodalis invasion of insect host cells (5). The first putative T3SS is approximately 23.5 kb in length and contains 24 predicted ORFs. This is preceded by a putative phage integrase gene and has an overall base composition (38.4 mol% G+C) that is significantly lower than that predicted for the E. amylovora genome (53.5 mol% G+C). The second putative T3SS is approximately 33.4 kb and contains 26 predicted ORFs with an overall base composition of 43.4 mol% G+C.

To determine the distribution of the new T3SS sequences among Erwinia strains, DNA probes were generated from PCR products from four predicted ORFs in the two putative T3SS sequences, ysaQ, yspB, ysaC2, and ysaH2. All of these probes hybridized to genomic DNAs from strains of E. amylovora but not to DNAs from other Erwinia strains (Table 5). Thus, if a Sodalis-like T3SS does exist in the Asian pear pathogens, it is divergent from that of E. amylovora. The type III (Hrp) secretion systems of E. pyrifoliae and E. amylovora associated with plant infection, in contrast, are highly conserved, sharing 84 to 96% nucleotide sequence similarity (21). E. amylovora is insect disseminated and has been isolated from orchard populations of several orders of insects with diverse habitats (10), although the exact interaction between the pathogen and its insect hosts remains poorly understood. The presence of sequences highly similar to insect endosymbionts could indicate a common ancestry and close phylogenetic relationship between Erwinia spp. and insect-related enteric bacteria, raising the possibility that an insect host might be serving as a mixing vessel for the exchange of genes between Erwinia strains and other enteric bacteria. Studies are under way to determine whether these genomic islands have a role in the virulence and spread of Erwinia spp.

TABLE 5.

Dot blot hybridization analysis of the distribution of gene sequences among various blight-causing Erwinia strains

| SSH clone | Predicted function | Hybridization with:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ea110 | Ea273 | Ea321 | MR1 | Ep1/96 | Ep4/97 | Ejp556 | Ejp557 | ||

| EP1 | EPS synthesis, similar to AmsF | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + |

| EJ1 | LPS biosynthesis | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| EJ2 | OrfL, unknown | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| EM4 | Polysaccharide biosynthesis | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| JE5 | Chitin-binding protein | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| PE3 | YopH-like PTPase (Ep1/96) | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| YopH-like PTPase (Ea273) | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | |

| PE5 | Bordetellahypothetical protein | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| EP6 | Galactose transporter MglA | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| EP7 | OrfX, unknown | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| EP2 | YsaQ | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| YsaC2 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | |

| YsaH2 | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | |

| YspB | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | |

| DspE (positive control) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

DIG-labeled DNA probes were created from PCR products of several other sequences isolated in this study to determine their distribution among Erwinia strains. Results of dot blot hybridizations are summarized in Table 5. Generally, Ea110−-specific sequences hybridized to all four strains of E. amylovora tested, with the predicted AmsF homolog sequence EP1 hybridizing to DNAs from strains Ejp556 and Ejp557 as well. Sequence JE5, a putative chitin-binding protein sequence specific to Ejp556, hybridized to all four of the Asian Erwinia strains tested. However, both probes derived from Ep1/96-specific sequences hybridized only to E. pyrifoliae strains (Table 5). A probe derived from the YopH homolog found in Ea273 hybridized to all four E. amylovora strains.

Summary.

In this study, we used SSH and dot blot hybridization screening and identified a number of genomic differences between Erwinia strains with differing host ranges, including components of two novel type III secretion systems in E. amylovora, a putative tyrosine phosphatase effector, and several sequences related to membrane transport or polysaccharide biosynthesis. The putative functions of genes that we identified are similar to those found in a recent study comparing the genome of a Xylella fastidiosa citrus strain with draft genome sequences of X. fastidiosa almond and oleander strains (1). This result is of interest because the X. fastidiosa pathogen is similar to E. amylovora in that gene-for-gene interactions between pathogen and host are currently unknown in both pathosystems. In contrast, comparative genomic analyses of different host-specific strains of P. syringae, a pathogen with known gene-for-gene interactions with plant hosts, indicated significant differences in the type III effector gene repertoires of these strains (6). Our work with Erwinia strains suggests that more subtle differences in exopolysaccharides, lipopolysaccharides, and transporters may be important in the interaction of blight-causing Erwinia strains and their hosts. The sequences we identified are candidates for analyses of their roles in host range differentiation and virulence.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the USDA CSREES and the Michigan Agricultural Experiment Station.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 September 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bhattacharyya, A., S. Stilwagen, N. Ivanova, M. D'Souza, A. Bernal, A. Lykidis, V. Kapatral, I. Anderson, N. Larsen, T. Los, G. Reznik, E. Selkov, Jr., T. L. Walunas, H. Feil, W. S. Feil, A. Purcell, J.-L. Lassez, T. L. Hawkins, R. Haselkorn, R. Overbeek, P. F. Predki, and N. C. Kyrpides. 2002. Whole-genome comparative analysis of three phytopathogenic Xylella fastidiosa strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:12403-12408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braun, P. G., and P. D. Hildebrand. 2005. Infection, carbohydrate utilization, and protein profiles of apple, pear, and raspberry isolates of Erwinia amylovora. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 27:338-346. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown, N. F., and I. R. Beacham. 2000. Cloning and analysis of genomic differences unique to Burkholderia pseudomallei by comparison with B. thailandensis. J. Med. Microbiol. 49:993-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bugert, P., and K. Geider. 1995. Molecular analysis of the ams operon required for exopolysaccharide synthesis of Erwinia amylovora. Mol. Microbiol. 15:917-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dale, C., S. A. Young, D. T. Haydon, and S. C. Welburn. 2001. The insect endosymbiont Sodalis glossinidius utilizes a type III secretion system for cell invasion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:1883-1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feil, H., W. S. Feil, P. Chain, F. Larimer, G. DiBartolo, A. Copeland, A. Lykidis, S. Trong, M. Nolan, E. Goltsman, J. Theil, S. Malfatti, J. E. Loper, A. Lapidus, J. C. Detter, M. Land, P. M. Richardson, N. C. Kyrpides, N. Ivanova, and S. E. Lindow. 2005. Comparison of the complete genome sequences of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae B728a and pv. tomato DC3000. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:11064-11069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giorgi, S., and M. Scortichini. 2005. Molecular characterization of Erwinia amylovora strains from different host plants through RFLP analysis and sequencing of hrpN and dspA/E genes. Plant Pathol. 54:789-798. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harakava, R., and D. W. Gabriel. 2003. Genetic differences between two strains of Xylella fastidiosa revealed by suppression subtractive hybridization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1315-1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heimann, M. F., and G. L. Worf. 1985. Fire blight of raspberry caused by Erwinia amylovora in Wisconsin. Plant Dis. 69:360. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hildebrand, M., E. Dickler, and K. Geider. 2000. Occurrence of Erwinia amylovora on insects in a fire blight orchard. J. Phytopathol. 148:251-256. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jock, S., and K. Geider. 2004. Molecular differentiation of Erwinia amylovora strains from North America and of two Asian pear pathogens by analyses of PFGE patterns and hrpN genes. Environ. Microbiol. 6:480-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim, W. S., L. Gardan, S.-L. Rhim, and K. Geider. 1999. Erwinia pyrifoliae sp. nov., a novel pathogen that affects Asian pear trees (Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai). Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:899-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim, W. S., M. Hildebrand, S. Jock, and K. Geider. 2001. Molecular comparison of pathogenic bacteria from pear trees in Japan and the fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora. Microbiology 147:2951-2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim, W. S., S. Jock, J.-P. Paulin, S.-L. Rhim, and K. Geider. 2001. Molecular detection and differentiation of Erwinia pyrifoliae and host range analysis of the Asian pear pathogen. Plant Dis. 85:1183-1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klena, J. D., R. S. D. Ashford II, and C. A. Schnaitman. 1992. Role of Escherichia coli K-12 rfa genes and the rfp gene of Shigella dysenteriae 1 in generation of lipopolysaccharide core heterogeneity and attachment of O antigen. J. Bacteriol. 174:7297-7307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maxson-Stein, K., G. C. McGhee, J. J. Smith, A. L. Jones, and G. W. Sundin. 2003. Genetic analysis of a pathogenic Erwinia sp. isolated from pear in Japan. Phytopathology 93:1393-1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGhee, G. C., E. L. Schnabel, K. Maxson-Stein, B. Jones, V. K. Stromberg, G. H. Lacy, and A. L. Jones. 2002. Relatedness of chromosomal and plasmid DNAs of Erwinia pyrifoliae and Erwinia amylovora. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:6182-6192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McManus, P. S., and A. L. Jones. 1995. Genetic fingerprinting of Erwinia amylovora strains isolated from tree-fruit crops and Rubus spp. Phytopathology 85:1547-1553. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyazaki, J., W. Ba-Thein, T. Kumao, H. Azaka, and H. Hayashi. 2002. Identification of a type III secretion system in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 212:221-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ritchie, D. F., and E. J. Klos. 1977. Isolation of Erwinia amylovora bacteriophage from the aerial parts of apple trees. Phytopathology 67:101-104. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shrestha, R., K. Tsuchiya, S. J. Baek, H. N. Bae, I. Hwang, J. H. Hur, and C. K. Lim. 2005. Identification of dspEF, hrpW, and hrpN loci and characterization of the HrpNEp gene in Erwinia pyrifoliae. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 71:211-220. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva, A. C. R., J. A. Ferro, F. C. Reinach, C. S. Farah, L. R. Furlan, R. B. Quaggio, C. B. Monteiro-Vitorello, M. A. Van Sluys, N. F. Almeida, L. M. C. Alves, A. M. do Amaral, M. C. Bertolini, L. E. A. Camargo, G. Camarotte, F. Cannavan, J. Cardozo, F. Chambergo, L. P. Ciapina, R. M. B. Cicarelli, L. L. Coutinho, J. R. Cursino-Santos, H. El-Dorry, J. B. Faria, A. J. S. Ferreira, R. C. C. Ferreira, M. I. T. Ferro, E. F. Formighieri, M. C. Franco, C. C. Greggio, A. Gruber, A. M. Katsuyama, L. T. Kishi, R. P. Leite, E. G. M. Lemos, M. V. F. Lemos, E. C. Locali, M. A. Machado, A. M. B. N. Madeira, N. M. Martinez-Rossi, E. C. Martins, J. Meidanis, C. F. M. Menck, C. Y. Miyaki, D. H. Moon, L. M. Moreira, M. T. M. Novo, V. K. Okura, M. C. Oliveira, V. R. Oliveira, H. A. Pereira, A. Rossi, J. A. D. Sena, C. Silva, R. F. de Souza, L. A. F. Spinola, M. A. Takita, R. E. Tamura, E. C. Teixeira, R. I. D. Tezza, M. Trindade dos Santos, D. Truffi, S. M. Tsai, F. F. White, J. C. Setubal, and J. P. Kitajima. 2002. Comparison of two Xanthomonas pathogens with differing host specificities. Nature 417:459-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stamm, L. V., N. R. Young, and J. G. Frye. 1996. Sequences of the Salmonella typhimurium mglA and mglC genes. Gene 171:131-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinberger, E. M., G.-Y. Cheng, and S. V. Beer. 1990. Characterization of a 56-kb plasmid of Erwinia amylovora Ea322: its noninvolvement in pathogenicity. Plasmid 24:12-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Sluys, M. A., M. C. de Oliveira, C. B. Monteiro-Vitorello, C. Y. Miyaki, L. R. Furlan, L. E. A. Camargo, A. C. R. da Silva, D. H. Moon, M. A. Takita, E. G. M. Lemos, M. A. Machado, M. I. T. Ferro, F. R. da Silva, M. H. S. Goldman, G. H. Goldman, M. V. F. Lemos, H. El-Dorry, S. M. Tsai, H. Carrer, D. M. Carraro, R. C. de Oliveira, L. R. Nunes, W. J. Siqueira, L. L. Coutinho, E. T. Kimura, E. S. Ferro, R. Harakava, E. E. Kuramae, C. L. Marino, E. Giglioti, I. L. Abreu, L. M. C. Alves, A. M. do Amaral, G. S. Baia, S. R. Blanco, M. S. Brito, F. S. Cannavan, A. V. Celestino, A. F. da Cunha, R. C. Fenille, J. A. Ferro, E. F. Formighieri, L. T. Kishi, S. G. Leoni, A. R. Oliveira, V. E. Rosa, Jr., F. T. Sassaki, J. A. D. Sena, A. A. de Souza, D. Truffi, F. Tsukumo, G. M. Yanai, L. G. Zaros, E. L. Civerolo, A. J. G. Simpson, N. F. Almeida, Jr., J. C. Setubal, and J. P. Kitajima. 2003. Comparative analyses of the complete genome sequences of Pierce's disease and citrus variegated chlorosis strains of Xylella fastidiosa. J. Bacteriol. 185:1018-1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viboud, G. I., and J. B. Bliska. 2005. Yersinia outer proteins: role in modulation of host cell signaling responses and pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59:69-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.York, G. M., and G. C. Walker. 1998. The succinyl and acetyl modifications of succinoglycan influence susceptibility of succinoglycan to cleavage by the Rhizobium meliloti glycanases ExoK and ExsH. J. Bacteriol. 180:4184-4191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang, Q., U. Melcher, L. Zhou, F. Z. Najar, B. A. Roe, and J. Fletcher. 2005. Genomic comparison of plant pathogenic and nonpathogenic Serratia marcescens strains by suppressive subtractive hybridization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:7716-7723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao, Y., S. E. Blumer, and G. W. Sundin. 2005. Identification of Erwinia amylovora genes induced during infection of immature pear tissue. J. Bacteriol. 187:8088-8103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]