Abstract

Pseudomonas fluorescens Q8r1-96 produces 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol (2,4-DAPG), a polyketide antibiotic that suppresses a wide variety of soilborne fungal pathogens, including Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici, which causes take-all disease of wheat. Strain Q8r1-96 is representative of the D-genotype of 2,4-DAPG producers, which are exceptional because of their ability to aggressively colonize and maintain large populations on the roots of host plants, including wheat, pea, and sugar beet. In this study, three genes, an sss recombinase gene, ptsP, and orfT, which are important in the interaction of Pseudomonas spp. with various hosts, were investigated to determine their contributions to the unusual colonization properties of strain Q8r1-96. The sss recombinase and ptsP genes influence global processes, including phenotypic plasticity and organic nitrogen utilization, respectively. The orfT gene contributes to the pathogenicity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in plants and animals and is conserved among saprophytic rhizosphere pseudomonads, but its function is unknown. Clones containing these genes were identified in a Q8r1-96 genomic library, sequenced, and used to construct gene replacement mutants of Q8r1-96. Mutants were characterized to determine their 2,4-DAPG production, motility, fluorescence, colony morphology, exoprotease and hydrogen cyanide (HCN) production, carbon and nitrogen utilization, and ability to colonize the rhizosphere of wheat grown in natural soil. The ptsP mutant was impaired in wheat root colonization, whereas mutants with mutations in the sss recombinase gene and orfT were not. However, all three mutants were less competitive than wild-type P. fluorescens Q8r1-96 in the wheat rhizosphere when they were introduced into the soil by paired inoculation with the parental strain.

Interest in biological control continues to increase in response to public concerns about the use of chemical pesticides and recognition of the need for environmentally benign plant disease control strategies (76). Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) have potential for development as biopesticides, biofertilizers, or phytostimulants, but only a few such products have been marketed, in part because the performance of introduced strains varies among fields and years. Variable root colonization can contribute significantly to this inconsistency because the introduced bacteria must attain threshold population sizes in the rhizosphere in order to be effective. Considerable research during the past 25 years has been directed toward understanding the biotic and abiotic factors that influence root colonization.

Our research has focused on colonization of the wheat rhizosphere by Pseudomonas fluorescens Q8r1-96, which produces the polyketide antibiotic 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol (2,4-DAPG). 2,4-DAPG-producing strains of P. fluorescens suppress root and seedling diseases of a variety of crops and play a key role in the natural biological control of take-all disease of wheat known as take-all decline (4, 19, 28, 49, 50, 65, 75). Strain Q8r1-96 is representative of D-genotype 2,4-DAPG producers as defined by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the phlD gene (phlD+) (39) and by repetitive-sequence-based PCR using the BOXA1R primer (42). D-genotype strains accounted for the majority of phlD+ isolates obtained from wheat or pea plants grown in Washington state soils that naturally suppress take-all, caused by Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici, and Fusarium wilt of pea, caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. pisi. Strain Q8r1-96 is exceptional because of its ability to establish and maintain large populations (up to 107 CFU/g of root) on the roots of wheat, pea (34, 51), and sugar beet (6) even when low doses are used. This special colonizing ability is typical of all D-genotype strains tested to date (34, 35, 51) and distinguishes these strains from typical rhizosphere pseudomonads.

Root colonization by introduced PGPR is a complex process that includes interactions among the introduced strain, the pathogen, and the indigenous rhizosphere microflora. All of these microorganisms interact with and influence each other in the context of the rhizosphere environment. Bacterial cell surface structures, such as flagella (18), fimbriae (11), and the O antigen of lipopolysaccharide (14), have been shown to influence the attachment of Pseudomonas cells to plant roots. Genes responsible for the biosynthesis of amino acids, vitamin B1 (67), a putrescine transport system (32), the NADH dehydrogenase NDH-1 (11), and ColR/ColS, a two-component regulatory system (16), also can influence the efficiency of root colonization. A site-specific sss recombinase gene, originally identified in P. aeruginosa 7NSK2 as an orthologue of the Escherichia coli site-specific recombinase gene xerC (26), has a role in root colonization in several strains (1, 15, 61) and even has been proposed as a potential target for improved colonization through genetic engineering (17). The protein encoded by sss, also known as xerC, belongs to the λ integrase family and plays a role in DNA rearrangement and phase variation (15, 61).

As one approach to identifying determinants of the unique rhizosphere competence of Q8r1-96 and related D-genotype strains, we hypothesized that these bacteria may interact with their plant hosts more intimately than other commensal pseudomonads interact with their plant hosts and that some of the broadly conserved bacterial genes critical to pathogenicity in such varied hosts as plants and animals (36, 54) may contribute to this unusual ability. Indeed, recent evidence of the presence of type III secretion genes in the PGPR strain P. fluorescens SBW25 (55, 56) and the presence of related genes in many other PGPR (41, 48, 58) suggests that such commonalities may occur more frequently than was previously anticipated. In this study, we focused on ptsP and orfT, two of the genes that contribute to the pathogenicity of P. aeruginosa in both plant and animal systems (53, 54) and are highly conserved (levels of identity, more than 70%) in the genomes of saprophytic rhizosphere pseudomonads, and on the sss recombinase gene because of its known contribution to the ability of bacteria to adapt to new environments. We identified and characterized the sss, orfT, and ptsP orthologues in P. fluorescens Q8r1-96, generated mutants with mutations in each gene, and determined the contributions of the genes to rhizosphere competence and strain competitiveness in the wheat rhizosphere.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

All bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli strains were routinely grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with standard concentrations of appropriate antibiotics (2). P. fluorescens strains were cultured at 28°C in King's medium B (KMB) (30) or pseudomonas agar P (PsP) (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). In experiments with P. fluorescens, antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 40 μg ml−1; rifampin, 100 μg ml−1; tetracycline, 10 μg ml−1; gentamicin, 2 μg ml−1; cycloheximide, 100 μg ml−1, chloramphenicol, 13 μg ml−1; and kanamycin, 25 μg ml−1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas fluorescens strains | ||

| Q8r1-96 | DAPG+ Rifr | 34 |

| Q8r1-96Gm | Q8r1-96 tagged with mini-Tn7-gfp2; DAPG+ Rifr Gmr | 71 |

| Q8r1-96sss | sss::EZ::TN<Kan2>; DAPG+ Rifr Kanr | This study |

| Q8r1-96ptsP | ptsP::EZ::TN<Kan2>; DAPG+ Rifr Kanr | This study |

| Q8r1-96orfT | orfT::EZ::TN<Kan2>; DAPG+ Rifr Kanr | This study |

| Q2-87 | DAPG+ Rifr | 74 |

| Escherichia coli strains | ||

| S17-1(λ-pir) | thi pro hsdM recA rpsL RP4-2 (Tetr::Mu) (Kanr::Tn7) | Lab collection |

| Top 10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) Φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 araΔ139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCPP47 | Broad-host-range cosmid derived from pCPP34, tandem cos+ par+ Tetr | 3 |

| pMOB3 | Kanr CamroriT sacB | 62 |

| pNOT19 | ColE1 oriV Ampr; accessory plasmid | 62 |

| pNOT19-sss-Kan | pNOT19 containing the 2.57-kb DNA SmaI fragment with sss interrupted by EZ::TN<Kan2> | This study |

| pNOT19-ptsP-Kan | pNOT19 containing the 3.8-kb DNA SmaI fragment with ptsP interrupted by EZ::TN<Kan2> | This study |

| pNOT19-orfT-KpnI-BamHI | pNOT19 containing the 1.2-kb fragment of orfT flanked by KpnI and BamHI sites | This study |

| pNOT19-orfT-BamHI-PstI | pNOT19 containing the 1.1-kb fragment of orfT flanked by BamH and PstI sites | This study |

| pNOT19-orfT-Kan | pNOT19 containing the 2.3-kb DNA SmaI fragment with orfT interrupted by EZ::TN<Kan2> | This study |

| pNOT19-sss-Kan-MOB3 | pNOT19-sss-Kan ligated with 5.8-kb NotI fragment from pMOB3 | This study |

| pNOT19-ptsP-Kan-MOB3 | pNOT19-ptsP-Kan ligated with 5.8-kb NotI fragment from pMOB3 | This study |

| pNOT19-orfT-Kan-MOB3 | pNOT19-orfT-Kan ligated with 5.8-kb NotI fragment from pMOB3 | This study |

| pME6010 | Broad-host-range plasmid; pVS1 oriV, p15a oriV, Pk Tetr | 23 |

| pME6010-ccdB | Gateway destination vector derived from pME6010 with ccdB-Camr cassette flanked by attR1 and attR2 | This study |

| pMK2010 | Gateway entry vector; ColE1 oriV, oriTRP4 Kanr, ccdB-Camr cassette flanked by attP1 and attP2 | 27 |

| pMK2010-sss | pMK2010 containing the 0.6-kb DNA fragment with sss | This study |

| pMK2010-ptsP | pMK2010 containing the 2.2-kb DNA fragment with ptsP | This study |

| pMK2010-orfT | pMK2010 containing the 1.0-kb DNA fragment with orfT | This study |

| pME6010sss | pME6010 containing the 0.6-kb DNA fragment with sss | This study |

| pME6010ptsP | pME6010 containing the 2.2-kb DNA fragment with ptsP | This study |

| pME6010orfT | pME6010 containing the 1.0-kb DNA fragment with orfT | This study |

DAPG+, strain produces 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol; Rifr, rifampin resistance; Gmr, gentamicin resistance; Ampr, ampicillin resistance; Tetr, tetracycline resistance; Kanr, kanamycin resistance; Camr, chloramphenicol resistance.

Construction of a cosmid library of P. fluorescens Q8r1-96.

Throughout this study, standard protocols were used for plasmid DNA purification, restriction enzyme digestion, ligation, and E. coli transformation (2). Total DNA of wild-type strain Q8r1-96 (51) was purified by using the Marmur procedure (22), partially digested with Sau3AI, and size fractionated on a 0.3% agarose gel. The 25- to 35-kb fraction was extracted by using a QIAEX II agarose gel extraction kit (QIAGEN, Santa Clarita, Calif.) and was ligated with vector arms prepared by digesting the broad-host-range cosmid vector pCPP47 (5) with BamHI and ScaI. The ligated DNA was packaged into λ particles with a Gigapack Gold kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), transduced into E. coli XL1-Blue MR, and selected on LB medium supplemented with tetracycline. Amplified and ordered copies of the genomic library were stored at −80°C in a freezing medium [2.5% (wt/vol) LB broth, 13 mM KH2PO4, 36 mM K2HPO4, 1.7 mM sodium citrate, 6.8 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.4 mM MgSO4, 10% glycerol].

Screening of the genomic library by hybridization and PCR.

The library was arrayed on BrightStar-Plus nylon membranes (7.4 by 11.4 cm; Ambion, Inc., Austin, Tex.) by replicating clones from the glycerol stocks with a 96-pin multiblot replicator (V&P Scientific, Inc., San Diego, Calif.) and a library copier that permits arraying in a 386-sample format. After arraying, the clones were grown overnight at 37°C and lysed in 0.4 M NaOH with subsequent UV cross-linking as described elsewhere (7).

The sss and orfT hybridization probes were amplified by PCR performed with Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, Wis.) and primers SSS_UP and SSS_LOW and primers ORFT_UP and ORFT_LOW (Table 2), respectively. The primers were developed by using the Oligo 6.65 software (Molecular Biology Insights, West Cascade, Colo.), based on the sss recombinase sequence from P. fluorescens F113 (GenBank accession number AF416734) and the orfT sequence from P. fluorescens SBW25 (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/P-fluorescens). The cycling program with the sss primers included a 1.5-min initial denaturation at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 61°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 1.2 min and a final extension at 68°C for 5 min. PCR amplification with the orfT primers was performed similarly except that the annealing step was at 62°C for 30 s and extension was at 72°C for 1 min.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this studya

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| SSS_UP | 5′ CGT CTT TCG CAC CTG ATG GA 3′ |

| SSS_LOW | 5′ CCT GGG ATG GGC ACT GTC A 3′ |

| ORFT_UP | 5′ CTA CGT TTA CAA CAG CTG GA 3′ |

| ORFT_LOW | 5′ TTC ACC CAG TTC GCT CAG T 3′ |

| ORFT_KpnI | 5′ AAG TAG TAC GGG GTG ACC AG 3′ |

| ORFT_Bam1 | 5′ TTT TGG ATC CAC GAA GGG TTT GCA 3′ |

| ORFT_Bam2 | 5′ GCT GGA TCC TCA GGA TGC GGT C 3′ |

| ORFT_Pst | 5′ GCC CCA GCA ATA CAA ACA AC 3′ |

| ORFT_seq1 | 5′ GAC GAT TTG TTC CGC GAT GC 3′ |

| ORFT_seq2 | 5′ TCC AGC CAG CCG CGC ACA C 3′ |

| PTSP3 | 5′ TCCAACGACCTCACCCAGTA 3′ |

| PTSP4 | 5′ CGCAGCATCCACTTCACCTT 3′ |

| PTSP5 | 5′ GGT GGT GAC ATT CAA GCG CGA 3′ |

| PTSP13 | 5′ GAG TGT GTT CAT CGC CAG CC 3′ |

| KAN_UP | 5′ TGG CAA GAT CCT GGT ATC GGT 3′ |

| KAN_LOW | 5′ GAA ACA TGG CAA AGG TAG CGT 3′ |

| Cm_UP | 5′ ATC CCA ATG GCA TCG TAA AGA 3 |

| Cm_LOW | 5′ AAG CAT TCT GCC GAC AT 3′ |

| sssF | 5′ GTG CCC TTT GTC AGC CTG ATC CTG TTC G 3′ |

| sssR | 5′ AGC TGG GTT CTA TGA TTC GTC GCC CTT GAT GC 3′ |

| sss2F | 5′ GGG GAC AAG TTT GTA CAA AAA AGC AGG CTT AGT GCC CTT TGT CAG C 3′ |

| ptsPF | 5′ GGA GGC TCT TCA ATG CTC AAT ACG CTG CGC AA 3′ |

| ptsPR | 5′ AGC TGG GTT CTA GAG GGT CTT GTT CGA AGC CG 3′ |

| orfTF | 5′ GGA GGC TCT TCA ATG CCC GAC CAA GAT GTA CG 3′ |

| orfTR | 5′ AGC TGG GTT CTA TGC CGT TGC TCC GGC CGA TT 3′ |

Oligonucleotides were designed by using the Oligo 6.65 primer analysis software and were constructed in this study.

The PCR products were labeled with [α-32P] dATP using the rediprime II random primer labeling system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech. Inc., Piscataway, N.J.) and were purified with a QIAGEN nucleotide removal kit (QIAGEN). The membranes on which the library was arrayed were prehybridized for 2 h at 60°C in a solution containing 3× SSC (60), 4× Denhardt's solution (60), 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 300 μg per ml of denatured salmon sperm DNA (Sigma). Prehybridized membranes were incubated overnight with ∼1 × 106 cpm of 32P-labeled probe under the same conditions and were washed with 2× SSC-0.1% SDS at room temperature (twice), 0.2× SSC-0.1% SDS at room temperature (twice), 0.2× SSC-0.1% SDS at 60°C (twice), and 0.1× SSC-0.1% SDS at 60°C (once). The conditions used for Southern hybridization with the orfT probe were the conditions described above, except that 4× SSC was used for prehybridization and high-stringency washes were performed at 58°C.

Clones containing ptsP were identified by PCR performed with primers PTSP3 and PTSP4 (Table 2), which were developed from the genome sequence of P. fluorescens SBW25. The library was divided into “primary” pools (i.e., pooled clones from each 96-well plate) that were further subdivided into “secondary” pools (containing clones from each 96-well plate pooled by rows or by columns). The purified cosmid DNA from “primary” and then “secondary” pools was screened by PCR using a program that included 1 min of initial denaturation at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 25 s, 60°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 20 s.

Shotgun sequencing and sequence analysis.

Selected cosmid clones carrying sss, ptsP, or orfT were sequenced by using the EZ::TN<Kan-2> transposition system (Epicenter Technologies, Madison, Wis.). Transposition reactions were performed in vitro according to the manufacturer's recommendations, and cosmids bearing insertions in the gene of interest were shotgun sequenced with transposon-specific primers by using an ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator v.3.0 Ready Reaction cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The sequence data were compiled with the Vector NTI software (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, Calif.) and were analyzed with the OMIGA 2.0 software (Accelrys, San Diego, Calif.). Database searches for similar protein sequences and protein motifs and domains were performed by using NCBI's BLAST network service (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST) and the MyHits Internet engine (46).

Allelic replacement in Q8r1-96.

A spontaneous rifampin-resistant derivative of Q8r1-96 (34) was used for gene replacement mutagenesis. To construct an sss mutant, the sss gene interrupted by EZ::TN<Kan-2> was amplified with primers SSS_UP and SSS_LOW by using KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase. The cycling program included 2 min of initial denaturation at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 61°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 1.2 min and a final extension at 68°C for 5 min. The amplification product was cloned into the SmaI site of the gene replacement vector pNOT19 (62). The resultant Kanr plasmids were digested with NotI and ligated into a 5-kb fragment carrying a pMOB3 cassette (62) linearized with NotI and containing the sacB and cat genes. The resultant plasmid was electroporated into E. coli S17-1(λ-pir), selected on LB medium supplemented with chloramphenicol and kanamycin, and mobilized from E. coli S17-(λ-pir) into P. fluorescens Q8r1-96 by using a biparental mating technique. Mutant clones were first selected on LB medium supplemented with rifampin, kanamycin, and 5% sucrose. Sucrose- and kanamycin-resistant clones were screened for the absence of plasmid-borne sacB, bla, and catgenes by PCR performed with primers SAC1 and SAC2 (38), primers BLA1 and BLA2 (38), and primers Cm_UP and Cm_LOW (Table 2), respectively. Primers KAN_UP and KAN_LOW (Table 2) were used to detect the presence of a kanamycin resistance gene in sss recombinase mutants, which also were screened by PCR performed with primers SSS_UP and SSS_LOW to confirm the absence of the wild-type sss allele.

A similar strategy was used to construct a ptsP mutant. Briefly, the full-length ptsP gene was amplified from strain Q8r1-96 with primers PTSP5 and PTSP13 (Table 2) and Expand Long PCR polymerase (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, Ind.). The cycling program consisted of 2 min of initial denaturation at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 10 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 3.5 min and a final extension at 68°C for 5 min. The amplification product was treated with T4 DNA polymerase, cloned into the SmaI site of pNOT19, mutagenized in vitro with EZ::TN<Kan-2>, digested with NotI, and ligated with a 5-kb fragment carrying a pMOB3 cassette (62) as described above. The resultant plasmids were electroporated into E. coli S17-1(λ-pir) and used for gene replacement as described above, except that the mutants were screened by PCR performed with primers PTSP5 and PTSP13 to confirm the absence of the wild-type allele.

To construct the orfTmutant, the 1,386-bp 5′ part of orfT was amplified by using KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase and oligonucleotides ORFT_KpnI and ORFT_Bam1 (Table 2). The cycling program included 2 min of initial denaturation at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 65°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 1 min and a final extension at 68°C for 5 min. The PCR product was digested with KpnI and BamHI, gel purified, and cloned into pNOT19. Next, a 1,246-bp fragment containing the 3′ part of orfT was amplified with primers ORFT_Pst and ORFT_Bam2 (Table 2) by using the same cycling program. The PCR product was digested with BamHI and PstI, gel purified, and cloned into pNOT19 containing the 5′ end of the orfT gene. These manipulations resulted in introduction of a unique BamHI site in orfT. This site was then used to insert the kanamycin resistance gene from EZ::TN<Kan-2>, yielding pNOT19-orfT-Kan. The resultant plasmids were digested with NotI, ligated with a 5-kb fragment of pMOB3 containing the sacB and cat genes, and electroporated into E. coli S17-1(λ-pir). Gene replacement mutagenesis was carried out essentially as described above, except that the mutants were screened by PCR performed with primers ORFT_seq1 and ORFT_seq2 to confirm the absence of the wild-type orfT allele. All mutant clones of each of the three genes were isogenic, and only one mutant clone was used for further experiments.

Construction of complemented mutants.

Full-length copies of sss, ptsP, and orfT were cloned into the stable broad-host-range plasmid vector pME6010 (23) by using Gateway Technology (Invitrogen). First, the genes were amplified by using a nested PCR protocol described by House et al. (27). Briefly, sss, ptsP, and orfT were amplified with gene-specific primers sssF and sssR, primers ptsPF and ptsPR, and primers orfTF and orfTR, respectively, and then attB sequences were introduced by reamplification with the secondary primers 2F and 2R (27) (or primers sss2F and 2R in the case of sss) (Table 2). All amplifications were carried out with KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase. The PCR products were then cloned into the entry plasmid pMK2010 (27) by using BP Clonase II (Invitrogen), sequenced to confirm gene integrity, and transferred with LR Clonase II (Invitrogen) to the destination vector pME6010 containing ccdB and attR cassettes (27). The resultant plasmids were electroporated (20) into Q8r1-96sss, Q8r1-96ptsP, or Q8r1-96orfT with a Gene Pulser II (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.).

Phenotypic characterization in vitro.

Polysaccharide production was scored visually after 3 days of growth on PsP by using a scale from 0 to 5, where 0 indicated a nonmucoid isolate and 5 indicated a moderately mucoid culture. Siderophore production was determined by measuring orange halos after 2 days of growth at 28°C on CAS agar plates (63). Exoprotease activity was detected by spotting 5 μl of an exponentially growing culture whose optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was adjusted to 0.1 on skim milk agar (59); a clearing zone surrounding the bacterial growth was measured after incubation for 48 and 72 h at 28°C. Production of hydrogen cyanide was monitored daily by using cyanide detection paper placed on petri dish lids for cultures grown on KMB agar amended with 0.44% glycine for 4 days at 28°C (3). All experiments described above were repeated twice with six replicates. Motility assays were performed on LB medium solidified with 0.3%, 0.5%, 1.0%, or 1.5% agar. Plates were inoculated with 5 μl of logarithmically growing bacterial cultures whose OD600 was adjusted to 0.1 and were incubated right side up at 28°C, and the diameter of outward expansion was measured after 24, 48, and 72 h. Experiments were repeated twice with four replicates per strain. Inhibition of G. graminis var. tritici by P. fluorescens Q8r1-96Gm and mutants of this strain was assayed on KMB agar as described previously (44). Carbon and nitrogen utilization profiles were generated by using Biolog SF-N2 and PM3 MicroPlates (Biolog, Inc., Hayward, Calif.), respectively, with 96 substrates each. Four independent repetitions were performed with each strain (40). Biolog assays were validated by using M9 minimal media supplemented with 0.4% d-galactose as a carbon source or with nitrogen sources at a concentration of 10 mM. Phloroglucinol compounds were extracted with ethyl acetate from bacterial cultures grown for 48 h at 27°C in KMB broth. The extracts were fractionated on a Waters NOVA-PAK C18 Radial-PAK cartridge (4 μm; 8 by 100 mm; Waters Corp., Milford, Mass.) as described previously (9). Two independent experiments with five replications were performed.

Rhizosphere colonization assays.

Rhizosphere colonization assays were performed with the sss recombinase, ptsP, and orfT mutants and Q8r1-96Gm, a gentamicin-resistant derivative of the parental strain tagged with mini-Tn7-gfp2 (71) to distinguish it from mutant strains in mixed-inoculation studies. Bacterial inocula were prepared and added to Quincy virgin soil as previously described (33) to obtain ∼1 × 104 CFU g−1 of soil and ∼0.5 × 104 CFU of each strain g−1 of soil (1:1 ratio) for single and mixed inoculations, respectively. The actual density of each strain was determined by assaying 0.5 g of inoculated soil as described by Landa et al. (33), and the control treatments consisted of soil amended with a 1% methylcellulose suspension. Experiments were repeated twice with six replicates per treatment. Spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L. cv. Penawawa) seeds were pregerminated on moistened sterile filter paper in petri dishes for 24 h in the dark and were sown in square pots (height, 6.5 cm; width, 7 cm) containing 200 g of Quincy virgin soil (33) inoculated with one or two bacterial strains. Wheat was grown for six successive cycles in a controlled-environment chamber at 15°C with a 12-h photoperiod. After 2 weeks of growth (one cycle), population densities of bacteria were determined as described by Mavrodi et al. (40). In order to determine the persistence of the mutants in the soil, the soil from pots that received the same treatment was decanted into plastic bags after the sixth cycle and stored at 20°C for 10 weeks before spring wheat was planted again. Plants were grown in a growth chamber for two successive 2-week cycles in the same controlled environment, processed, and analyzed as described below.

Population densities of the introduced strains were monitored by the modified dilution-endpoint method (43, 71). Briefly, individual wheat root systems were placed in 10 ml of sterile distilled water, vortexed, and sonicated. The soil suspensions were serially diluted in 96-well microtiter plates containing 1/3× KMB broth supplemented with rifampin, cycloheximide, ampicillin, and chloramphenicol and incubated for 72 h at room temperature (an OD600 of ≥0.07 was scored as positive) (43). After 3 days, the cultures were replicated into fresh 96-well plates containing KMB broth amended with kanamycin or gentamicin to distinguish between strains in mixed inoculations. Population densities of total culturable heterotrophic bacteria were determined by performing the same assay in 0.1× tryptic soy broth supplemented with cycloheximide (43).

Data analysis.

All treatments in competitive colonization experiments were arranged in a complete randomized design. Statistical analyses were performed by using appropriate parametric and nonparametric procedures with the STATISTIX 8.0 software (Analytical Software, St. Paul, Minn.). All population data were converted to log CFU g−1 of soil or log CFU g−1 (fresh weight) of root. Differences in population densities among treatments were determined by standard analysis of variance, and mean comparisons among treatments were performed by using Fisher's protected least-significant-difference test (P = 0.05) or the Kruskal-Wallis all-pairwise comparison test (P = 0.05). The area under the colonization progress curve (AUCPC), which represented the total rhizosphere colonization for all six cycles (34), was calculated with SigmaPlot V. 8.0 (SYSTAT Software Inc., Richmond, Calif.). Data from phenotypic assays were compared by using a two-sample t test or the Wilcoxon rank sum test (P = 0.05).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sss, ptsP, and orfT sequences of P. fluorescens Q8r1-96 have been deposited in the GenBank nucleotide sequence database under accession numbers AY172655, AY816321, and AY816322, respectively.

RESULTS

Identification, cloning, and characterization of sss, orfT, and ptsP.

Initial screening of the Q8r1-96 library by colony hybridization or, in the case of ptsP, by PCR yielded eight sss-positive clones, eight orfT-positive clones, and one ptsP-positive clone, all of which were further mapped by Southern hybridization. Briefly, purified cosmid DNA from each clone was digested with EcoRI, KpnI, and SacI, resolved on an agarose gel, blotted, and hybridized with the corresponding biotin-labeled probe. One clone containing each gene of interest then was selected for EZ::TN<Kan-2>-mediated DNA sequencing.

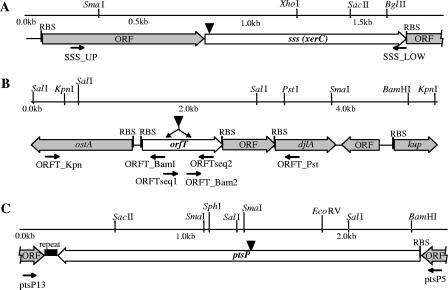

Included in sss-positive cosmid clone 7D10 was a 1,851-bp contig containing a predicted open reading frame with similarity to genes encoding numerous bacterial and phage site-specific recombinases (Fig. 1A). The sss gene encodes a predicted 299-amino-acid protein with a molecular mass of 33,772 Da and is flanked by two open reading frames coding for a conserved hypothetical protein and a putative hydrolase, YigB.

FIG. 1.

Restriction maps and locations of individual genes in regions of the P. fluorescens Q8r1-96 genome containing sss (A), orfT (B), and ptsP (C). Inverted solid triangles indicate the positions of EZ::TN<Kan-2> insertions, and small horizontal arrows indicate PCR primers used in this study. The shaded arrows indicate the positions of genes and open reading frames (ORF) that were not relevant in the present study. RBS, ribosome-binding site.

The deduced Sss protein is highly similar to putative recombinases from P. fluorescens WCS365 (NCBI accession number CAA72946; 100% identity), P. fluorescens Pf-5 (NCBI accession number AAY95204; 88% identity), Pseudomonas putida KT2440 (NCBI accession number NP_747331; 76% identity), and P. aeruginosa PAO1 (NCBI accession number Q51566; 71% identity). Further analyses revealed the presence of a XerC profile listed in the HAMAP database of orthologous microbial protein families (21) and two Pfam domains (residues 5 to 89 and 111 to 282) associated with phage integrases. Searches against the Cluster of Orthologous Groups of Proteins (COG) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG) indicated that the protein belongs to COG4973 and COG0582, which contain XerC-like site-specific recombinases (E value, 3e−94). Finally, the protein structure predicted by the fold recognition server 3D-PSSM (29) closely resembled that of the site-specific XerD recombinase from E. coli (68).

Shotgun sequencing of cosmid clone 7D2, which hybridized to the orfT probe, revealed a 5,176-bp contig (Fig. 1B) that included a predicted open reading frame with similarity to Orf338 from P. aeruginosa PA14 (69). The gene, referred to here as orfT, is preceded by a putative ribosome-binding site, GGAGA, and encodes a predicted 341-amino-acid protein with a molecular mass of 38,655 Da. The contig contains a number of other open reading frames, two of which are located immediately downstream of orfT and probably are cotranscribed with it. These genes encode a conserved hypothetical protein and a putative DnaJ-like protein.

Database searches revealed that orfT is highly conserved in sequenced bacterial genomes, and a blastp search against the nonredundant GenBank data set returned more than 40 hits with E values less than 1e−50. The deduced OrfT protein is most similar to its counterparts from P. fluorescens Pf-5 (NCBI accession number AAY94838; 84% identity), Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae DC3000 (NCBI accession number AAO54097; 82% identity), P. putida KT2440 (NCBI accession number NP_742571; 74% identity), and P. aeruginosa PA14 (NCBI accession number AAD22455; 67% identity). OrfT is a member of COG3178, which contains predicted phosphotransferases (E value, 1e−90), and further analyses revealed the presence of a Pfam domain associated with the aminoglycoside phosphotransferase enzyme family (residues 152 to 234). The OrfT structure predicted by 3D-PSSM (29) is related to the structures of aminoglycoside 3′-phosphotransferases from Enterococcus faecalis (10) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (45).

ptsP-positive cosmid clone 5F9 contained a 2,586-bp contig that included a predicted open reading frame with similarity to numerous bacterial pstP genes (Fig. 1C). The ptsP gene encodes a predicted 759-amino-acid protein with a molecular mass of 83,208 Da and is flanked in Q8r1-96 by a well-conserved ribosome-binding site, GGAG, and a putative transcriptional terminator comprised of a 93-bp region with imperfect dyad symmetry.

The deduced PtsP protein is highly similar to its orthologues from P. fluorescens Pf-5 (NCBI accession number AAY95089; 96% identity), P. syringae pv. syringae DC3000 (NCBI accession number AAO58710; 92% identity), Azotobacter vinelandii (NCBI accession number CAA74995; 87% identity), and P. aeruginosa PAO1 (NCBI accession number NP_249028; 86% identity). The results of domain searches revealed a conserved PROSITE phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP)-utilizing enzyme signature (residues 620 to 638) and Pfam GAF (residues 17 to 154), N-terminal (residues 178 to 302), mobile (residues 318 to 399), and TIM barrel (residues 424 to 715) domains associated with PEP-utilizing enzymes. Finally, searches against the COG database indicated that the protein belongs to COG3605 containing bacterial PtsP proteins (E value, 0.0), and the protein structure predicted by 3D-PSSM (29) was related to the structures of pyruvate phosphate dikinases from Clostridium symbiosum (24) and Trypanosoma brucei (13).

Phenotypic characteristics of the sss, ptsP, and orfT mutations.

The motilities of wild-type Q8r1-96 and sss, ptsP, and orfT mutants of this strain were compared on LB medium solidified with different agar concentrations. The motility of the wild-type strain was significantly (P = 0.05) greater than the motilities of the ptsP and orfT mutants on 0.3% agar (Table 3). In contrast, the motility of the sss mutant did not differ from that of Q8r1-96. When higher concentrations of agar were used, neither the mutants nor the wild type showed the ability to swarm.

TABLE 3.

Phenotypic effects of sss, ptsP, and orfT mutations in P. fluorescens Q8r1-96

| Strain | Siderophore productiona | Exoprotease production afterb:

|

Motility afterc:

|

MAPG productiond | 2,4-DAPG productiond | Total production of phloroglucinal-related compoundsd | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48 h | 72 h | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | |||||

| Q8r1-96 | 8.5 a | 6.7 a | 9.8 a | 20.2 a | 32.3 a | 38.7 a | 2.1 × 106 a (100) | 9.4 × 106 a (100) | 12.0 × 106 b (100) |

| Q8r1-96sss | 7.4 b | 7.5 b | 11.2 b | 19.2 a | 30.8 a | 36.5 a | 2.8 × 106 a (132) | 12.7 × 106 b (134) | 16.1 × 106 a (133) |

| Q8r1-96ptsP | 11.4 b | 4.5 b | 8.7 b | 17 b | 29.6 b | 35.1 b | 1.1 × 106 be (54) | 5.7 × 106 b (60) | 7.6 × 106 ae (63) |

| Q8r1-96orfT | 8.0 a | 6.8 a | 10.7 a | 17.2 b | 27.8 b | 32.8 b | 2.5 × 106 a (120) | 11.5 × 106 a (122) | 14.6 × 106 a (121) |

Siderophore production was determined by measuring orange halos (in millimeters) after 2 days of growth at 28°C on CAS agar plates. The values are means for four replicate plates. Values followed by the same letter are not significantly different as determined by a two-sample t test in which each mutant was compared separately to the wild type.

Zone of casein digestion on milk agar plates (in millimeters) after 48 and 72 h of bacterial growth. The values are means for three replicate plates. Values followed by the same letter are not significantly different as determined by a two-sample t test in which each mutant was compared separately to the wild type.

Diameter of bacterial spread (in millimeters) on 0.3% LB agar. The values are means for six replicate plates after 24, 48, and 72 h of bacterial growth. Values followed by the same letter are not significantly different as determined by a two-sample t test in which each mutant was compared separately to the wild type.

Production expressed as peak area/optical density. The values are means for five replicate extractions. Values followed by the same letter are not significantly different as determined by a two-sample t test (unless indicated otherwise) in which each mutant was compared separately to the wild type. The values in parentheses are percentages of production relative to production by Q8r1-96, which was set at 100%.

Significance was determined by the Wilcoxon rank sum test (α = 0.05).

The siderophore excretion detected on CAS agar plates was significantly greater for the ptsP mutant, not altered for the orfT mutant, and significantly lower for the sss mutant compared with the siderophore excretion detected for the parental strain (Table 3). Differences in colony morphology were observed on some media. The sss and orfT mutants were more mucoid on PsP than the parental strain, and the ptsP mutant was less mucoid. Isolated colonies of the ptsP mutant, but not isolated colonies of the sss and orfT mutants, appeared to be more yellow than those of the parental strain when they were grown on LB medium supplemented with glucose. The extracellular protease activity was significantly greater for the sss mutant, not altered for the orfT mutant, and significantly lower for the ptsP mutant compared with the extracellular protease activity of wild-type strain Q8r1-96 (Table 3). None of the mutants was impaired for hydrogen cyanide (HCN) production.

The growth kinetics of the sss, ptsP, and orfT mutants in 1/3× KMB and M9 media supplemented with glycerol were indistinguishable from those of wild-type strain Q8r1-96. Likewise, the carbon and nitrogen substrate utilization profiles of the sss and orfT mutants did not differ from those of Q8r1-96 on the 96 substrates contained in Biolog SF-N2 and PM3 microplates. In contrast, the ptsP mutant grew more slowly on d-galactose as a source of carbon and on l-cysteine as a source of nitrogen, both in the Biolog assays and in appropriately supplemented cultures grown in M9 medium.

Phloroglucinol production and fungal inhibition in vitro.

P. fluorescens Q8r1-96 and the sss, orfT, and ptsP mutants all produced detectable quantities of 2,4-DAPG, as well as monoacetylphloroglucinol (MAPG) and three other uncharacterized phloroglucinol-related compounds (Table 3). The sss and orfT mutants produced larger amounts of 2,4-DAPG and total phloroglucinol-related compounds than wild-type strain Q8r1-96 produced (for the orfT mutant only production of total phloroglucinol-related compounds was significantly greater [P = 0.05]), whereas the ptsP mutant produced significantly less MAPG and 2,4-DAPG. The reduced phloroglucinol production by the ptsP mutant was correlated with the diminished ability of this mutant to inhibit growth of G. graminis var. tritici in vitro; the hyphal inhibition indices (ratios of the distance between the edge of the bacterial colony and the fungal mat to the distance between the edge of the colony and the center of the mat) for this mutant and the parental strain were 0.0 and 0.16, respectively, after 6 days. In contrast, overproduction of 2,4-DAPG by the sss and orfT mutants was not correlated with increased fungal inhibition, probably due to differences in the relative amounts of phloroglucinol compounds accumulated during the different growth regimens. The hyphal inhibition indices for the sss and orfT mutants at 6 days postinoculation were 0.12 and 0.08, respectively.

Impact of the sss, ptsP, and orfT mutations on rhizosphere colonization by Q8r1-96.

The impact of the sss, ptsP, and orfT mutations on the rhizosphere competence of Q8r1-96 was assessed by performing competitive wheat root colonization assays under greenhouse conditions. The sss, ptsP, and orfT mutant strains were introduced into raw Quincy virgin soil either individually or, to test their competitiveness with the parental strain, in pairwise combinations (1:1 ratio) with strain Q8r1-96Gm. Figures 2A to C show the population dynamics of the strains over six 2-week growth cycles. In each case, the population densities of the introduced strains at cycle 0, the beginning of the experiments, were equivalent. In both single and mixed inoculations, the population sizes of the wild type and the sss recombinase and orfT mutant strains increased by 4 orders of magnitude by the end of cycle 1 and then slowly declined over the following six cycles.

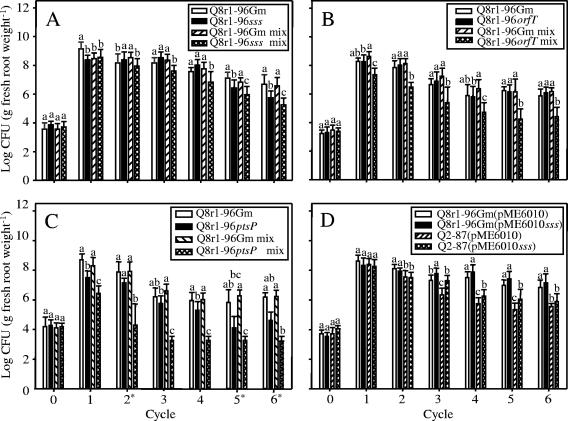

FIG. 2.

Population dynamics of Pseudomonas strain Q8r1-96Gm, sss (A), orfT (B), and ptsP (C) mutants, and strains Q8r1-96Gm and Q2-87 bearing pME6010 or pME6010sss (D) on the roots of wheat cv. Penawawa grown in Quincy virgin soil for six consecutive 2-week cycles as described in Materials and Methods. Each strain was introduced into the soil at a final density of approximately log 4 CFU per g of soil (cycle 0) in single inoculations and approximately 0.5 × 104 CFU per g of soil in mixed inoculations. The bars indicate means, and the error bars indicate standard deviations. The same letter above bars for the same cycle indicates that the means are not significantly different (P = 0.05) according to a Fisher's protected least-significant-difference test (unless indicated otherwise). Cycles marked with an asterisk were analyzed by a Kruskal-Wallis test (P = 0.05).

The population densities of both Q8r1-96Gm and the sss mutant in the wheat rhizosphere fluctuated when the strains were introduced individually. The densities of the two strains were similar in cycles 3 and 4, and the density of the sss mutant was less than that of the wild-type strain in cycles 5 and 6 (Fig. 2A). However, the values for the AUCPC and mean colonization (measures of colonization across all cycles) did not differ significantly, indicating that the wild type and the sss mutant were equivalent in terms of rhizosphere colonization (Table 4). However, when introduced in combination with the parental strain, the sss mutant colonized the wheat rhizosphere significantly less than Q8r1-96Gm colonized the wheat rhizosphere in cycles 2 through 6, and the AUCPC and mean colonization values of the mutant were significantly lower than those of the wild type (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Population densities of indigenous, introduced wild-type, and mutant strains on the roots of wheat grown in Quincy virgin soila

| Expt | Strain(s) | Population densities (AUCPC)b:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q8r1-96Gm | Mutant | Q8r1-96Gm and mutant (1:1) | Controlc | ||

| 1 | Indigenous bacteria | 8.75 bc | 9.02 a | 8.92 ab | 8.59 c |

| Q8r1-96Gm | 7.8 ad (45.3 a) | ND | 7.8 ad (45.0 a) | ND | |

| Q8r1-96sss | ND | 7.6 ad (44.5 a) | 7.0 bd(41.4 b) | ND | |

| 2 | Indigenous bacteria | 8.68 bd | 8.96 ad | 8.79 abd | 8.66 abd |

| Q8r1-96Gm | 6.8 a (39.5 b) | ND | 7.1 a (41.3 a) | ND | |

| Q8r1-96orfT | ND | 6.9 a (39.9 b) | 5.4 b (32.0 c) | ND | |

| 3 | Indigenous bacteria | 8.27 b | 8.51 a | 8.54 a | 8.46 ab |

| Q8r1-96Gm | 6.8 a (39.8 a) | ND | 6.9 a (40.3 a) | ND | |

| Q8r1-96ptsP | ND | 5.7 b (34.3 b) | 4.0 c (24.3 c) | ND | |

Raw Quincy virgin soil was treated with ∼104 CFU per g of soil of Q8r1-96Gm and/or Q8r1-96sss, Q8r1-96orfT, or Q8r1-96ptsP. Mixed-inoculation treatments contained a 1:1 mixture of competing strains (∼0.5×104 CFU per g of soil of each strain). Rhizosphere population densities of bacteria were determined by the terminal dilution endpoint assay as described in Materials and Methods.

The values are mean population densities in log CFU per g (fresh weight) of root for six cycles except cycle 0. Mean population densities in each experiment were analyzed separately. Within each experiment, populations of indigenous bacteria were analyzed separately from populations of introduced wild types and mutants. The values in parentheses are the areas under the rhizosphere colonization progress curves (AUCPC) for introduced bacteria for six cycles. Different letters after values indicate that there is a statistically significant difference as determined by Fisher's protected least-significant-difference test (P = 0.05) (unless indicated otherwise). ND, not detected.

Treatment without bacterial inoculation.

The significance of differences between bacterial densities was determined by the Kruskal-Wallis all-pairwise comparison test (P = 0.05).

As observed for the sss mutant, the population densities of the orfT mutant in single-inoculation treatments fluctuated over the six growth cycles (Fig. 2B). The densities of the two strains did not differ significantly in any of the cycles, and the AUCPC and mean colonization values of the orfT mutant did not differ from those of Q8r1-96Gm (Table 4). In contrast, when the strains were introduced together into the soil, Q8r1-96Gm consistently outcompeted the orfT mutant. The population size of Q8r1-96Gm was significantly greater than that of the mutant in cycles 1 through 6 (Fig. 2B), and the AUCPC and mean colonization values of the mutant were significantly lower than those of the wild type in the mixed inoculations (Table 4).

Unlike the sss and orfT mutants, the ptsP mutant colonized the wheat rhizosphere significantly less (P = 0.05) than Q8r1-96Gm when the strains were introduced individually (Fig. 2C, cycles 1 and 4). The population densities of the two strains were similar in the other cycles, but the AUCPC and mean colonization values for Q8r1-96Gm were significantly higher than those for the ptsP mutant (Table 4). In mixed treatments, the ptsP mutant consistently colonized the wheat rhizosphere less than Q8r1-96Gm in cycles 1 through 6 (Fig. 2C), and the AUCPC and mean colonization values for the mutant were significantly lower (P = 0.05) than those for the wild type (Table 4).

The population densities for total culturable aerobic bacteria in the wheat rhizosphere for all experiments were more than log 8.4 CFU/g root. Mean colonization values of indigenous bacteria are shown in Table 4.

In order to evaluate survival of the wild type and the sss, orfT, and ptsP mutants in the absence of wheat roots, after the sixth cycle of the colonization experiments soils were stored at 20°C for 10 weeks, and then wheat seeds were sown again. The mean population densities recovered from the roots after two consecutive cycles are shown in Table 5. In soil into which the sss mutant and the wild-type strain had been introduced separately, comparable populations of the two strains were recovered from the rhizosphere, suggesting that the strains had survived equally well in the bulk soil during storage. In the soil into which the two strains had been coinoculated, a significantly larger population of the wild type than of the mutant was recovered, consistent with both the larger wild-type population at the time of storage and the tendency of the wild type to outcompete the mutant in mixed inoculations. In contrast, in the soils into which the ptsP or orfT mutant and the wild type had been introduced, whether separately or together, the recovered populations of the mutants were significantly smaller than those of the wild type (Table 5), suggesting that the mutants did not survive well in the absence of roots.

TABLE 5.

Population densities of introduced wild-type and mutant strains in the rhizosphere of wheat sown in soil after 10 weeks of storagea

| Expt | Strain | Population densitiesb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q8r1-96Gm | Mutant | Q8r1-96Gm and mutant (1:1) | ||

| 1 | Q8r1-96Gm | 6.0 a (6.8) | ND | 5.8 a (6.6) |

| Q8r1-96sss | ND | 5.5 a (5.7) | 4.3 b (5.2) | |

| 2 | Q8r1-96Gm | 6.5 ac (5.9) | ND | 5.8 bc (6.2) |

| Q8r1-96orfT | ND | 5.7 bc (6.0) | 3.5 cc (4.4) | |

| 3 | Q8r1-96Gm | 5.4 a (6.2) | ND | 5.7 a (6.2) |

| Q8r1-96ptsP | ND | 3.3 b (4.6) | 3.3 b (3.2) | |

Strain recovery was determined as the mean population density on roots of wheat plants of growth following a 10-week fallow period as described in Materials and Methods.

The values are mean population densities in log CFU per g (fresh weight) of root for two cycles except cycle 0. Mean population densities in each experiment were analyzed separately. The values in parentheses are population densities in log CFU per g (fresh weight) of root after cycle 6 (before soil was stored for 10 weeks). Different letters after values indicate that there is a statistically significant difference as determined by Fisher's protected least-significant-difference test (P = 0.05) (unless indicated otherwise). ND, not detected.

The significance of differences between population densities after two cycles was determined by the Kruskal-Wallis all-pairwise comparison test (P = 0.05).

Rhizosphere colonization assays also were conducted with the sss, orfT, and ptsP mutants complemented with the corresponding wild-type genes carried on pME6010 (23), a stable, low-copy-number plasmid vector. The mean population densities and AUCPC values for six cycles (Table 6) indicated that the plasmid-borne functional gene copies did indeed complement the chromosomal mutations in sss, orfT, and ptsP. Only when the complemented ptsP mutant was present in a 1:1 mixture with the wild type was the AUCPC value less than that for the wild-type strain.

TABLE 6.

Population densities of P. fluorescens Q8r1-96Gm and complemented mutants on the roots of wheat grown in Quincy virgin soila

| Expt | Strain | Population densities (AUCPC)b

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q8r1-96Gm(pME6010) | Complemented mutant | Q8r1-96Gm(pME6010) and mutant (1:1) | ||

| 1 | Q8r1-96Gm(pME6010) | 7.6 a (43.7 abc) | ND | 7.5 a (40.0 cc) |

| Q8r1-96sss(pME6010sss) | ND | 7.6 a (44.6 ac) | 7.8 a (40.5 bcc) | |

| 2 | Q8r1-96Gm(pME6010) | 7.6 a (44.2 ab) | ND | 7.4 a (43.2 b) |

| Q8r1-96orfT(pME6010orfT) | ND | 7.7 a (44.8a) | 7.4 a (42.8 b) | |

| 3 | Q8r1-96Gm(pME6010) | 7.6 a (43.8 ab) | ND | 7.4 a (43.0 b) |

| Q8r1-96ptsP(pME6010ptsP) | ND | 7.7 a (45.1 a) | 7.4 a (41.0 c) | |

Raw Quincy virgin soil was treated with ∼104CFU g−1 soil of Q8r1-96Gm(pME6010) and/or Q8r1-96sss(pME6010sss), Q8r1-96orfT(pME6010orfT), or Q8r1-96ptsP(pME6010ptsP). Mixed-inoculation treatments contained a 1:1 mixture of competing strains (∼0.5×104 CFU g−1 soil of each strain). Rhizosphere population densities of bacteria were determined by the terminal dilution endpoint assay described in Materials and Methods.

The values are mean population densities in log CFU per g (fresh weight) of root for six cycles except cycle 0. Mean population densities in each experiment were analyzed separately. The values in parentheses are areas under the rhizosphere colonization progress curves (AUCPC) for introduced bacteria for six cycles. Different letters after values indicate that there is a statistically significant difference as determined by Fisher's protected least-significant-difference test (P = 0.05) (unless indicated otherwise). ND, not detected.

The significance of differences between AUCPC was determined by the Kruskal-Wallis all-pairwise comparison test (P = 0.05).

Dekkers et al. (17) reported that the ability of some strains of P. fluorescens to colonize root tips of tomato is improved upon introduction of a plasmid-borne sss-containing fragment. To determine whether sss from P. fluorescens Q8r1-96 enhanced colonization of entire wheat root systems grown in nonsterile soil under our experimental conditions, we introduced pME6010sss into Q8r1-96, an exceptional root colonizer, and into the closely related but less aggressive strain Q2-87. The population dynamics of the two strains harboring either the empty vector or pME6010sss for six cycles are shown in Fig. 2D, and the mean colonization values and AUCPC values are shown in Table 7. Only in one of six cycles did Q8r1-96Gm harboring additional copies of sss establish a larger (approximately threefold) population in the wheat rhizosphere than the strain carrying an empty plasmid did. In contrast, the presence of pME6010sss in Q2-87 significantly improved root colonization 9.1-, 3.3-, and 5.2-fold in cycles 3, 4, and 5 (Fig. 2D). However, statistical analysis of the mean population density and AUCPC values across all six cycles indicated that there were no significant differences between treatments (Table 7).

TABLE 7.

Population densities of strains Q8r1-96Gm and Q2-87 bearing pME6010 or pME6010sss on the roots of wheat grown in Quincy virgin soil

| Straina | Mean population densityb | AUCPCe |

|---|---|---|

| Q8r1-96Gm(pME6010) | 7.6 a | 43.7 ab |

| Q8r1-96Gm(pME6010sss) | 7.8 a | 44.6 a |

| Q2-87(pME6010) | 6.5 b | 38.9 c |

| Q2-87(pME6010sss) | 6.9 ab | 40.5 bc |

| Controlc | NDd | ND |

Raw Quincy virgin soil was treated with ∼104 CFU per g of soil of strain Q8r1-96Gm or Q2-87 containing the empty vector pME6010 or the pME6010 derivative with cloned sss. Rhizosphere population densities of bacteria were determined by the terminal dilution endpoint assay as described in Materials and Methods.

The values are mean population densities in log CFU per g (fresh weight) of root for six cycles except cycle 0. Different letters after values in the same column indicate that there is a statistically significant difference as determined by Fisher's protected least-significant-difference test (P = 0.05).

Treatment without bacterial inoculation.

ND, not detected.

The values are areas under the colonization progress curves for introduced bacteria for six cycles. Different letters after values in the same column indicate that there is a statistically significant difference as determined by the Kruskal-Wallis all-pairwise comparison test (P = 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The P. fluorescens genes studied in this work were chosen for analysis based on the important roles that they play in other bacterial systems. Of the three genes, sss probably is the best known in relation to rhizosphere microbiology; it encodes a subunit of a site-specific tyrosine recombinase involved in proper segregation of circular bacterial chromosomes during cell division and in the stable maintenance of some plasmids (8). In E. coli, the orthologue XerC, together with XerD, forms a heterotetrameric enzyme complex that catalyzes two consecutive pairs of strand exchanges at a 28-bp dif site in the chromosome. In the complex, XerC specifically cleaves and exchanges the top DNA strand. However, XerC and XerD are similar to each other and act in a cooperative fashion. The Xer recombinase is highly conserved in most species of Enterobacteriaceae, as well as in many other bacterial genera, including Pseudomonas (73). In fluorescent pseudomonads, xerC (called sss) initially was identified in P. aeruginosa as a gene that complemented a deficiency in pyoverdin production (26), but further functional studies revealed that sss encodes a site-specific recombinase homologous to XerC from E. coli (8). Later studies established that this sss-encoded recombinase plays an important role in competitive rhizosphere colonization by P. fluorescens WCS365, where its activity is linked to phenotypic variation and high mutation frequencies in the GacA/GacS global two-component regulatory system (15, 37, 61). The role of phenotypic variation in rhizosphere Pseudomonas spp. has been reviewed recently (72).

The results of the sequence analysis suggest that the sss-like gene that we cloned from P. fluorescens Q8r1-96 indeed encodes a true xerC homologue. We included this gene in our studies of root colonization because it was shown previously to contribute to rhizosphere competence and phenotypic variation in fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. in a variety of crops (1, 15, 61) and because we wondered if it played a significant role in the unusual colonization properties of strain Q8r1-96. Under gnotobiotic conditions, the sss mutant of P. aeruginosa 7NSK2 colonized potato root tips 10- to 1,000-fold less than the wild type colonized potato root tips in mixed inoculations, and the corresponding mutant of P. fluorescens WCS365 was impaired in colonization of tomato root tips in potting soil and in colonization of radish and wheat root tips under gnotobiotic conditions (15). These gnotobiotic systems are important in identifying genes that may function in colonization, but the results obtained under such conditions must be validated in natural soil. In our studies, the bacteria were added to a natural field soil that was cropped to wheat for multiple cycles, allowing rhizosphere colonization to proceed for months under controlled conditions in the presence of indigenous microflora and percolating water. Under these conditions, the sss mutant of Q8r1-96 colonized the wheat rhizosphere to the same extent as its wild-type parent colonized the wheat rhizosphere, and a deficiency in rhizosphere competence of the mutant became apparent only when plants were inoculated with a mixture containing both strains (Table 4).

Inactivation of sss in P. fluorescens Q8r1-96 resulted in a phenotype similar to that of the sss mutant of P. fluorescens WCS365 (15). Q8r1-96sss did not differ from the wild-type parent in its carbon and nitrogen utilization profiles, growth rate, motility, or swarming behavior (Table 3). Among the minor differences observed were decreased siderophore production, also reported in P. aeruginosa 7NSK2 (26), and production of elevated amounts of exoprotease and phloroglucinol-related compounds (Table 3). The fact that the extracellular protease activity or HCN production of the sss mutant was not impaired suggests that the GacA/GacS regulatory circuitry, which coordinately regulates the production of secondary metabolites and exoprotease (77), was not disturbed in Q8r1-96sss. We have no immediate explanation for the phenotypic changes observed in the sss mutant, and we attribute them to the pleiotropic nature of the sss mutation.

The second gene studied in this work, orfT, was selected for analysis based on its role in interactions between P. aeruginosa PA14 and Arabidopsis thaliana (53). Like the sss mutant of Q8r1-96, the orfT mutant did not differ from the wild type in the ability to colonize the rhizosphere of wheat when it was introduced into the soil alone, but it colonized significantly less than the parental strain colonized when the two strains were introduced together (Table 4). Inactivation of orfT resulted in reduced motility and production of elevated total amounts of phloroglucinol-related compounds (Table 3). On the other hand, the orfT mutant did not differ from the wild type in carbon and nitrogen utilization profiles or the production of exoprotease, hydrogen cyanide, and siderophores. Furthermore, the mutant was indistinguishable from P. fluorescens Q8r1-96 on KMB and LB media supplemented with 2% glucose, but it was slightly more mucoid on PsP.

The results of computer analyses of OrfT indicate that its orthologues are found in all Pseudomonas genomes sequenced to date. The predicted proteins share a HRDxxxN motif with eukaryotic and some prokaryotic Ser/Thr and Tyr protein kinases (66) and some aminoglycoside phosphotransferases that are responsible for bacterial resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics, such as streptomycin and kanamycin (45). The motif represents part of an active center where the conserved aspartate residue acts as a catalytic base (45). Despite these findings, this eukaryote-like protein kinase motif is too generic to provide any clues concerning the specificity of OrfT, and the similarity to aminoglycoside phosphotransferases is partial and limited to about 40% of the polypeptide chain. Thus, at this point the exact function of orfT in the rhizosphere competence of P. fluorescens Q8r1-96 remains unclear.

Like orfT, the third gene studied in this work, ptsP, was chosen for study based on its role in interactions between P. aeruginosa PA14 and A. thaliana (53). In contrast to the sss and orfT mutants, the rhizosphere competence of Q8r1-96ptsP was strongly impaired, and its rhizosphere population densities were significantly lower than those of the wild type in both single and mixed inoculations (Table 4 and Fig. 2C). The mutant lost the ability to maintain a density greater than 106 CFU/g root during extended cycling, which is a key characteristic of Q8r1-96 and all D-genotype isolates (6, 34, 35, 51). In cycles 5 and 6, the density of the mutant was ≤103 CFU/g root, at least 3 orders of magnitude less than that of the wild type. The ptsP mutant exhibited altered morphology, reduced motility and exoprotease activity, and an increased level of fluorescence. It produced significantly smaller amounts of MAPG and 2,4-DAPG (ca. 54% and 60% of the wild-type levels). Carbon and nitrogen substrate utilization profiling revealed that Q8r1-96ptsP grew more slowly on d-galactose and l-cysteine, respectively.

The pleiotropic phenotype exhibited by Q8r1-96ptsP appears to reflect the proposed global regulatory function of the ptsP gene, which is highly conserved in the genomes of P. fluorescens Pf01, SBW25, and Pf-5. The product of ptsP forms part of an alternative PEP:carbohydrate phosphotransferase system (PTS). PTSs are found in a wide range of gram-positive and gram-negative microorganisms and have been best studied in enteric bacteria, where they are involved in sensing, transport, and metabolism of carbohydrates, as well as in catabolite repression and inducer exclusion. The first component of a typical PTS is a carbohydrate-specific multisubunit (or multidomain) enzyme II (EII) that forms a membrane translocation channel and phosphorylates the incoming sugar (47). The second part of a PTS is involved in the phosphorylation of all PTS carbohydrates. It lacks specificity and is comprised of cytoplasmic enzyme I (EI) and histidine protein (HPr).

In E. coli, ptsP encodes a nitrogen-specific EI paralogue called EINtr that, together with EIINtr and NPr (paralogues of EIIFru and HPr, respectively), forms a regulatory PTS phosphoryl transfer chain (52). Functional analyses have shown that this chain is involved in sugar-dependent utilization of certain amino acids and somehow links the metabolism of carbon and nitrogen. In P. putida, EIINtr either positively or negatively (and largely in a glucose-independent fashion) controls the expression of over 100 genes, some of which are members of the σ54 regulon (12). Based on the results of this study, it was proposed that EIINtr, which together with EINtr and NPr presumably forms an alternative PTS in P. putida, functions as a global regulatory factor rather than as a promoter-specific regulatory factor. Genes coding for EINtr also were described for A. vinelandii (64), Bradyrhizobium japonicum (31), P. aeruginosa (69), and Legionella pneumophila (25). In these microorganisms, as in E. coli, ptsP primarily plays a regulatory role and does not directly participate in phosphorylation or utilization of carbohydrates. Similarly, the ptsP mutant of Q8r1-96 did not differ considerably from the wild type in utilization of the sugars, amino acids, and organic acids included among the substrates present in Biolog MicroPlates. Recently, it was reported that ptsP plays an important role in the regulation of pyocyanin production but did not influence the quorum-sensing system in P. aeruginosa (78).

In conclusion, the data presented in this paper suggest novel functions for two genes, ptsP and orfT, that previously were linked with pathogenesis in P. aeruginosa. The ptsP and orfT mutants of Q8r1-96 did not have nonspecific growth defects in vitro, and the effects of the mutations became apparent only when the mutants were tested in the rhizosphere, either individually or in competition with the parental strain. In this respect, both genes fulfill the criteria for “true” rhizosphere colonization determinants, as described by Lugtenberg et al. (36). To our knowledge, this is the first report to provide evidence that ptsP is involved in rhizosphere colonization by fluorescent pseudomonads. The results of sequence analyses suggest that in P. fluorescens Q8r1-96, as in P. aeruginosa (57) and P. putida (12), PtsP (EINtr) forms part of the regulatory phosphoryl transfer chain that may coordinate the metabolism of carbon and nitrogen. Unfortunately, despite the fact that EINtr, EIINtr, and NPr have been purified and characterized biochemically, their exact functions remain poorly understood even in E. coli (70). However, if PtsP has a role in integrating carbon and nitrogen utilization, as it is thought to have in some bacteria, then the mutant phenotype might be manifested differently in the synthetic media used in our growth studies than in the complex mixture of sugars, organic acids, and amino acids present in root exudates. More comprehensive growth studies are necessary to determine whether such differences may account for the limited effects of the mutation on growth in vitro compared to the profound impact observed in the wheat rhizosphere.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Research Initiative Competitive Grants Program (grants 2003-35319-13800 and 2003-35107-13777).

We thank K. Hansen, A. Park, M. Young Son, and J. Mitchell for technical assistance and Nathalie Walter for comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 25 August 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achouak, W., S. Conrod, V. Cohen, and T. Heulin. 2004. Phenotypic variation of Pseudomonas brassicacearum as a plant root-colonization strategy. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 17:872-879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.). 2002. Short protocols in molecular biology, 5th ed. John Wiley and Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 3.Bakker, A. W., and B. Schippers. 1987. Microbial cyanide production in the rhizosphere in relation to potato yield reduction and Pseudomonas spp. mediated plant growth stimulation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 19:451-457. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bangera, M. G., and L. S. Thomashow. 1999. Identification and characterization of a gene cluster for synthesis of the polyketide antibiotic 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol from Pseudomonas fluorescens Q2-87. J. Bacteriol. 181:3155-3163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer, D. W., and A. Collmer. 1997. Molecular cloning, characterization, and mutagenesis of a pel gene from Pseudomonas syringae pv. lachrymans encoding a member of the Erwinia chrysanthemi PelADE family of pectate lyases. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 10:369-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergsma-Vlami, M., M. E. Prins, M. Staats, and J. M. Raaijmakers. 2005. Assessment of genotypic diversity of antibiotic-producing Pseudomonas spp. in the rhizosphere by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:993-1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birren, B., E. D. Green, S. Klapholz, M. R. Myers, H. Riethman, and J. Roskams. 1999. Genome analysis: a laboratory manual, vol. 3. Cloning systems. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 8.Blakely, G. W., A. O. Davidson, and D. J. Sherratt. 2000. Sequential strand exchange by XerC and XerD during site-specific recombination at dif*. J. Biol. Chem. 275:9930-9936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonsall, R. F., D. M. Weller, and L. S. Thomashow. 1997. Quantification of 2.4-diacetylphloroglucinol produced by fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. in vitro and in the rhizosphere of wheat. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:951-955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burk, D. L., W. C. Hon, A. K.-W. Leung, and A. M. Berghuis. 2001. Structural analyses of nucleotide binding to an aminoglycoside phosphotransferase. Biochemistry 40:8756-8764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camacho Carvajal, M. M. 2000. Molecular characterization of the role of type 4 pili, NADH-I and PyrR in rhizosphere colonization of Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365. Ph.D. thesis. Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

- 12.Cases, I., J.-A. Lopez, J.-P. Albar, and V. De Lorenzo. 2001. Evidence of multiple regulatory functions for the PtsN (IIANtr) protein of Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 183:1032-1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cosenza, L. W., F. Bringaud, T. Baltz, and F. M. D. Vellieux. 2001. The 3.0 Å resolution crystal structure of glycosomal pyruvate phosphate dikinase from Trypanosoma brucei. J. Mol. Biol. 318:1417-1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dekkers, L. C., A. J. van der Bij, I. H. M. Mulders, C. C. Phoelich, R. A. R. Wentwoord, D. C. M. Glandorf, C. A. Wijffelman, and B. J. J. Lugtenberg. 1998. Role of the O-antigen of lipopolysaccharide, and possible roles of growth rate and of NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (nuo) in competitive tomato root-tip colonization by Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 11:763-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dekkers, L. C., C. C. Phoelich, L. van der Fits, and B. J. J. Lugtenberg. 1998. A site-specific recombinase is required for competitive root colonization by Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:7051-7056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dekkers, L. C., C. J. P. Bloemendaal, L. A. de Weger, C. A. Wijffelman, H. P. Spaink, and B. J. J. Lugtenberg. 1998. A two-component system plays an important role in the root-colonizing ability of Pseudomonas fluorescens strain WCS365. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 11:45-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dekkers, L. C., I. H. M. Mulders, C. C. Phoelich, T. F. C. Chin-a-Woeng, A. H. M. Wijfjes, and B. J. J. Lugtenberg. 2000. The sss colonization gene of the tomato-Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. radicis-lycopersici biocontrol strain Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 can improve root colonization of other wild-type Pseudomonas spp. bacteria. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13:1177-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Weger, L. A., C. I. M. Van der Vlugt, A. H. M. Wijfjes, P. A. H. B. M. Bakker, B. Schippers, and B. Lugtenberg. 1987. Flagella of a plant-growth-stimulating Pseudomonas fluorescens strain are required for colonization of potato roots. J. Bacteriol. 169:2769-2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duffy, B. K., and G. Défago. 1997. Zinc improves biocontrol of Fusarium crown and root rot of tomato by Pseudomonas fluorescens and represses the production of pathogen metabolites inhibitory to bacterial antibiotic biosynthesis. Phytopathology 87:1250-2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enderle, P. J., and M. A. Farwell. 1998. Electroporation of freshly plated Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells. BioTechniques 25:954-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gattiker, A., K. Michoud, C. Rivoire, A. H. Auchincloss, E. Coudert, T. Lima, P. Kersey, M. Pagni, C. J. A. Sigrist, C. Lachaize, A.-L. Veuthey, E. Gasteiger, and A. Bairoch. 2003. Automatic annotation of microbial proteomes in Swiss-Prot. Comput. Biol. Chem. 27:49-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerhardt, P., R. G. E. Murray, W. Wood, and N. R. Krieg (ed.). 1994. Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 23.Heeb, S., Y. Itoh, T. Nishijyo, U. Schnider, C. Keel, J. Wade, U. Walsh, F. O'Gara, and D. Haas. 2000. Small, stable shuttle vectors based on the minimal pVS1 replicon for use in gram-negative, plant-associated bacteria. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13:232-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herzberg, O., C. C. Chen, S. Liu, A. Tempczyk, A. Howard, M. Wei, D. Ye, and D. Dunaway-Mariano. 2002. Pyruvate site of pyruvate phosphate dikinase: crystal structure of the enzyme-phosphonopyruvate complex, and mutant analysis. Biochemistry 41:780-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higa, F., and P. H. Edelstein. 2001. Potential virulence role of the Legionella pneumophila ptsP ortholog. Infect. Immun. 69:4782-4789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofte, M., Q. Dong, S. Kourambas, V. Krishapillai, D. Sharratt, and M. Mergeay. 1994. The sss gene product, which affects pyoverdin production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa 7NSK2, is a site-specific recombinase. Mol. Microbiol. 14:1011-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.House, B. L., M. W. Mortimer, and Kahn, M. L. 2004. New recombination methods for Sinorhizobium meliloti genetics. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2806-2815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keel, C., U. Schnider, M. Maurhofer, C. Voisard, J. Laville, U. Burger, P. Wirthner, D. Haas, and G. Défago. 1992. Suppression of root diseases by Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0: importance of the bacterial secondary metabolite 2,4-diacetylphlorogluciol. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 5:4-13. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelley, L. A., R. M. MacCallum, and M. J. E. Sternberg. 2000. Enhanced genome annotation using structural profiles in the program 3D-PSSM. J. Mol. Biol. 299:499-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.King, E. O., M. K. Ward, and D. Raney. 1954. Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescein. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 44:301-307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.King, N. D., and M. R. O'Brian. 2001. Evidence for direct interaction between enzyme INtr and aspartokinase to regulate bacterial oligopeptide transport. J. Biol. Chem. 276:21311-21316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuiper, I., G. V. Bloemberg, S. Noreen, J. E. Thomas-Oates, and B. J. J. Lugtenberg. 2001. Increased uptake of putrescine in the rhizosphere inhibits competitive root colonization by Pseudomonas fluorescens strain WCS365. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 14:1096-1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landa, B. B., H. A. E. de Werd, B. B. McSpadden Gardener, and D. M. Weller. 2002a. Comparison of three methods for monitoring populations of different genotypes of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing Pseudomonas fluorescens in the rhizosphere. Phytopathology 92:129-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Landa, B. B., O. V. Mavrodi, J. Raaijmakers, B. B. McSpadden Gardener, L. S. Thomashow, and D. M. Weller. 2002b. Differential ability of genotypes of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing Pseudomonas fluorescens strains to colonize the roots of pea plants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3226-3237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landa, B. B., D. V. Mavrodi, J., Raaijmakers, L. S. Thomashow, and D. M. Weller. 2003. Interactions between strains of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing Pseudomonas fluorescens strains in the rhizosphere of wheat. Phytopathology 93:982-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lugtenberg, B. J. J., L. C. Dekkers, and G. V. Bloemberg. 2001. Molecular determinants of rhizosphere colonization by Pseudomonas. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 39:461-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinez-Granero, F., S. Capdevila, M. Sanchez-Contreras, M. Martin, and R. Rivilla. 2005. Two site-specific recombinases are implicated in phenotypic variation and competitive rhizosphere colonization in Pseudomonas fluorescens. Microbiology 151:975-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mavrodi, D. V., R. F. Bonsall, S. M. Delaney, M. J. Soule, G. Phillips, and L. S. Thomashow. 2001. Functional analysis of genes for biosynthesis of pyocyanin and phenazine-1-carboxamide from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Bacteriol. 183:6454-6465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mavrodi, O. V., B. B. McSpadden Gardener, D. V. Mavrodi, D. M. Weller, and L. S. Thomashow. 2001. Genetic diversity of phlD from 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. Phytopathology 91:35-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mavrodi, O. V., D. V. Mavrodi, D. M. Weller, and L. S. Thomashow. 2006. The role of dsbA in root colonization by Pseudomonas fluorescens Q8r1-96. Microbiology 152:863-872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mazurier, S., M. Lemunier, S. Siblot, C. Mougel, and P. Lemanceau. 2004. Distribution and diversity of type III secretion system-like genes in saprophytic and phytopathogenic fluorescent pseudomonas. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 49:455-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McSpadden Gardener, B. B., K. L. Schroeder, S. E. Kalloger, J. M. Raaijmakers, L. S. Thomashow, and D. M. Weller. 2000. Genotypic and phenotypic diversity of phlD-containing Pseudomonas isolated from the rhizosphere of wheat. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1939-1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McSpadden Gardener, B. B., D. V. Mavrodi, L. S. Thomashow, and D. M. Weller. 2001. A rapid PCR-based assay characterizing rhizosphere populations of 2,4-DAPG-producing bacteria. Phytopathology 91:44-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McSpadden Gardener, B. B., and D. M. Weller. 2001. Changes in populations of rhizosphere bacteria associated with take-all disease of wheat. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4414-4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nurizzo, D., S. C. Shewry, M. H. Perlin, S. A. Brown, J. N. Dholakia, R. L. Fuchs, T. Deva, E. N. Baker, and C. A. Smith. 2003. The crystal structure of aminoglycoside-3′-phosphotransferase-IIa, an enzyme responsible for antibiotic resistance. J. Mol. Biol. 327:491-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pagni, M., V. Ionnidis, L. Cerutti, M. Zahn-Zabal, C. V. Jongeneel, and L. Falquet. 2004. Myhits: a new interactive resource for protein annotation and domain identification. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:W332-W335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Postma, P. W., J. W. Lengeler, and G. R. Jacobson. 1996. Phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems, p. 1149-1174. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 48.Preston, G. M., N. Bertrand, and P. B. Rainey. 2001. Type III secretion in plant growth-promoting Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25. Mol. Microbiol. 41:999-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raaijmakers, J. M., D. M. Weller, and L. S. Thomashow. 1997. Frequency of antibiotic-producing Pseudomonas spp. in natural environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:881-887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raaijmakers, J. M., and D. M. Weller. 1998. Natural plant protection by 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing Pseudomonas fluorescens in take-all decline soils. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 11:144-152. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Raaijmakers, J. M., and D. M. Weller. 2001. Exploiting the genetic diversity of Pseudomonas spp: characterization of superior colonizing P. fluorescens strain Q8r1-96. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2545-2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rabus, R., J. Reizer, I. Paulsen, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1999. Enzyme INtr from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 274:26185-26191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]