Abstract

Three-dimensional reconstructions from electron cryomicrographs of the rotor of the flagellar motor reveal that the symmetry of individual M rings varies from 24-fold to 26-fold while that of the C rings, containing the two motor/switch proteins FliM and FliN, varies from 32-fold to 36-fold, with no apparent correlation between the symmetries of the two rings. Results from other studies provided evidence that, in addition to the transmembrane protein FliF, at least some part of the third motor/switch protein, FliG, contributes to a thickening on the face of the M ring, but there was no evidence as to whether or not any portion of FliG also contributes to the C ring. Of the four morphological features in the cross section of the C ring, the feature closest to the M ring is not present with the rotational symmetry of the rest of the C ring, but instead it has the symmetry of the M ring. We suggest that this inner feature arises from a domain of FliG. We present a hypothetical docking in which the C-terminal motor domain of FliG lies in the C ring, where it can interact intimately with FliM.

The bacterial flagellum of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium has a reversible rotary motor powered by the proton gradient across the cell's plasma membrane. The flagellar filament, with its corkscrew shape, converts the motor's torque to thrust. Counterclockwise (CCW) rotation of the filament by the motor pushes the cell through the liquid medium, whereas a brief intervening burst of clockwise (CW) rotation causes the cell to tumble. Following the CW burst, the motor resumes CCW rotation, and the cell swims off in a new direction. Approximately 40 proteins are involved in the regulation, assembly, and operation of the flagellum. At least 24 of them are components of the completed flagellum. Of the 24, only 5, i.e., MotA, MotB, FliG, FliM, and FliN, appear to be involved in torque generation (for reviews, see references 1, 2, and 25). MotA and MotB (8, 37) form a proton channel through the plasma membrane (3, 38); they are assumed to form the stator (7, 18). The remaining three are cytoplasmic proteins that form the switch complex (49) and are assumed to be part of the rotor. FliG appears to be most directly involved in torque generation (14, 22), and the C-terminal domain of FliG contains key charged residues that interact with charged residues in MotA (53). The N-terminal portion of FliG interacts with FliF, the transmembrane component of the rotor (20, 31), which functions as a mechanical mount for the rotor and couples the motor to the rod or drive shaft. FliM is involved in switching between CCW and CW rotation (34) and binds phospho-CheY (48), tipping the motor's bias toward CW rotation. FliN appears to play a smaller role in rotation and switching (14, 22) but has an important role in flagellar export (46).

The gross structural features of the flagellum are a filamentous axial structure and a set of coaxial rings (Fig. 1). MotA and MotB, the putative stator, form a ring of about 10 studs in the plasma membrane (17, 18). FliM and FliN form most of the C ring (12, 52). FliF, a transmembrane protein, forms the S and M rings (45), and there is evidence (see Fig. 5a in reference 11) that FliG is bound to the cytoplasmic face of FliF, causing the M ring to appear thicker. FliM and FliN do not contribute to the M ring (12, 41), but it remains unclear whether FliG forms part of the C ring. The similarity in structure between the M rings prepared from wild-type strains and a strain with a mutation resulting in a covalent fusion of the full-length FliF and FliG proteins suggests that there are equal numbers of copies (∼26) of FliF and FliG in the hook-basal body complex (HBB) (15, 41). The C ring contains about 34 copies of FliM and about 100 copies of FliN (42, 52). In vitro, one molecule of FliM can form a complex with four molecules of FliN (6). The symmetry of, and hence the number of, subunits in the C ring is not fixed but varies from 31 to 38 (51).

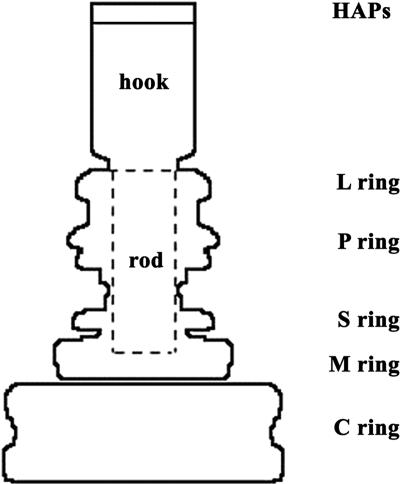

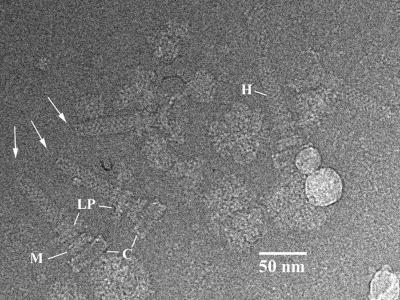

FIG. 1.

Schematic drawing of the hook and basal body. At the tip of the HBB are the three hook-associated proteins. The hook extends from them to the rod. The rod passes through the L and P rings, which form a bushing through the lipopolysaccharide and the peptidoglycan layers. It stops just short of the M ring, which is embedded in the plasma membrane. The M ring passes through the membrane and extends into the cytoplasm. The C ring lies beneath the M ring held by thin connections sometimes seen in images of HBBs.

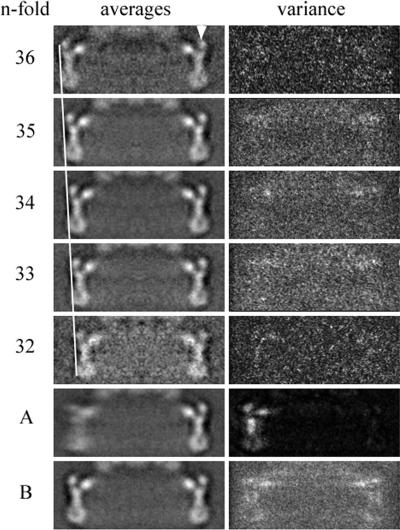

FIG. 5.

Class averages and variances of the C ring. Images of the hook-basal body complexes were sorted into classes based on the symmetry of the C ring (see Materials and Methods). The members of each symmetry class were averaged (left column) and the variances calculated (right column). Note how low the variance is for the sorted C rings compared to the high variance seen when the C rings (rows A and B) are averaged without sorting. The C rings are aligned on the rightmost feature (arrowhead at right top). The line along the left side accentuates the decrease of diameter with symmetry, as expected from the results of Young et al. (51) Row A shows the average of all the averaged images when aligned on the right-side feature. The left-side feature, as expected, is blurred. Note the variance in row A is low on the right and high on the left due to the misalignment of left-side features. Row B is an average over all images independent of symmetry. The alignment in this case was done using whole C rings. The variance is high because of the variation in diameter present when the averaged C rings have not been sorted according to symmetry.

There are high-resolution structures for the C-terminal two-thirds of FliG (5), for the C-terminal portion of FliN (6), and for HrcQBC, a homolog of FliN found in the type III secretion system of Pseudomonas syringae (9). The structure of the solved portion of FliG has two globular domains connected by a long alpha helix. There is also a structure for EscJ, a homolog of FliF found in the type III secretion complex of Escherichia coli. EscJ has less than half the mass of FliF (50) and has sequence homology to the N-terminal portion of FliF. It is not known how the components of the motor interact at a molecular level, but there are clues provided by mutational, binding, and cross-linking studies (23, 27, 32, 40). What is needed are three-dimensional (3D) maps of the rotor into which one can fit atomic structures of the components as they become known.

Here we present 3D reconstructions of the C ring and M ring from a CW-locked mutant of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (SJW2811). The CW-locked phenotype arises from the deletion of three amino acids, P169, A170, and A171, in FliG (43). These residues are located at the N-terminal end of the extended alpha helix that connects the C-terminal and middle domains. In addition to the known variation in the C-ring symmetry, we find evidence for variation in the symmetry of the M ring. We present 3D maps of the 33-, 34-, and 35-fold-symmetric C rings and of 24-, 25-, and 26-fold-symmetric M rings. We find no simple correlation between the symmetry of the C ring and that of the M ring. However, the inner domain of the C ring, which lies nearest the M ring, appears not to have the symmetry of the C ring but rather to have that of the M ring. We suggest that this feature may correspond to the C-terminal domain of FliG.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample preparation.

The strain SJW2811 (43) was kindly provided by Robert Macnab. The gene for FliC (flagellin) was deleted by Tn10 transposon insertion (19) to remove the filament, which is about 99% of the mass of the flagellum. This strain, NRF2811, was used as the source for HHBs. HBBs were purified as previously described by Francis et al. (12). Samples were kept on ice or at 4°C during all steps.

Electron microscopy.

Grids for electron microscopy were prepared in a cold room at 4°C. Samples of HBB in TET buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 8.0) were applied to Quantifoil (Jena, Germany) type R1.2/1.3 grids, which have 1.2-μm holes separated by 1.3 μm; blotted with Whatman no. 1 filter paper (Florham Park, NJ); and plunged into liquid ethane cooled by liquid N2. Grids were stored and handled at liquid N2 temperatures. An electron dose of 1,000 to 1,500 electrons per nm2 was used, and images were collected on SO-163 film (Kodak, Rochester, NY) at a magnification of ×50,000 on an F-20 microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR) equipped with a field emission gun. In the microscope, the specimen was held at −170°C in an Oxford cryo-holder (Gatan Inc., Warrendale, PA) cooled by liquid N2.

Image processing.

Micrographs were digitized at 7-μm per pixel, using a Zeiss SCAI scanner (Oberkochen, Germany). Pixels were averaged to yield 14-μm sampling corresponding to 0.28-nm/pixel in the specimen. The defocus for the micrographs was determined using CTFFIND2 (29). CTFFIND2 divides the micrograph into segments, calculates the power spectrum from each segment, and produces the average power spectrum for all the segments in each micrograph. The choice of segment size was important, and we found that segments of 512 by 512 were satisfactory while smaller segments were not. From the averaged power spectrum, CTFFIND2 determines the defocus and astigmatism. Micrographs with significant astigmatism were not used. A radially averaged power spectrum produced by CTFFIND2 is shown in Fig. 2a. Whole micrographs, as opposed to individual particle images, were corrected for the contrast transfer function (CTF). We used the CTF differently in different steps of the analysis. In the determination of alignment parameters, a phase-only correction was applied. To generate a 3D reconstruction, the micrographs were corrected for both phase and amplitude by using a Wiener filter (33), FC(X) = [F(X) · CTF(X)]/[|CTF(X)|2 + NS], where FC is the corrected Fourier coefficient, F is the measured Fourier coefficient, X is the reciprocal space position, and NS is the noise-to-signal ratio.

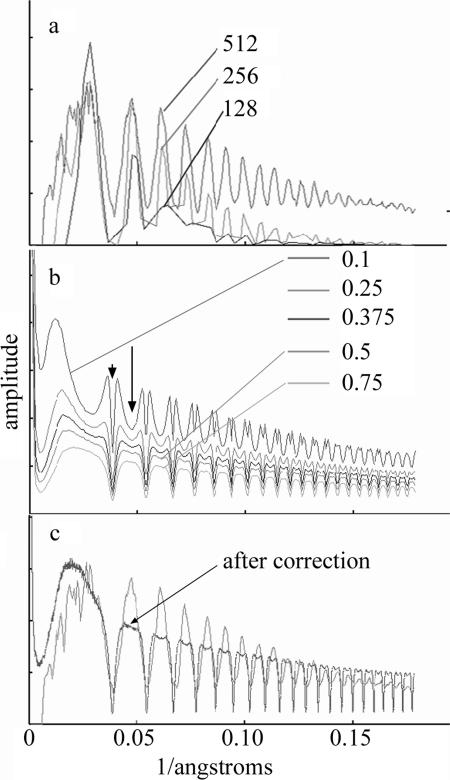

FIG. 2.

Data used to determine the best method for correction of the contrast transfer function. (a) Plots of rotationally averaged Fourier amplitude versus radius. Individual micrographs were divided into a set of segments having dimensions of 128 by 128, 256 by 256, or 512 by 512. The power spectra from each of the segments were averaged together, and the result was rotationally averaged. A background subtraction is applied to the power spectra as part of the program CTFFIND2 (29). Note that the 512-by-512 area produced the best result. (b) Plots showing the effect of the choice of noise-to-signal ratio on the corrected power spectrum (see Materials and Methods). When the value is too small, minima are introduced into what should be peaks (arrow), and bifurcated peaks are produced where there should be a node (arrowhead). At a signal-to-noise ratio of 0.5, this artifact disappears. The power spectra have been calculated using SPIDER (13) and have not had any background subtracted. (c) Comparison of the original CTF determined in a 512-by-512 box with the CTF-corrected power spectrum of the whole micrograph. When the whole micrograph is corrected, note how well the positions of the nodes are preserved and how close the nodes are to zero.

To determine a value for NS, we corrected a whole micrograph according to the equation above but tried different values of NS from 0.1 to 1.0. When the NS was too small, the procedure generated artifacts in which we saw valleys where peaks were expected and bifurcated peaks at the positions of nodes (see curve in Fig. 2b where NS = 0.1). A constant signal-to-noise ratio of 0.5 was found to be the smallest value that eliminated these two artifacts (Fig. 2b). In Fig. 2c, we plot the corrected CTF for the whole micrograph.

Images were windowed from the CTF-corrected micrographs by using HELIXBOXER(24). To generate maps of the C rings or the M rings, just the C-ring or M-ring portions of the images were used. A generous rectangular mask was applied to the images, removing most of the M ring in the case of the C-ring alignment or most of the LP and C rings in the case of the M-ring alignment. The multireference alignment functions of SPIDER (13) were used both to sort the images into groups according to rotational symmetry and to determine the orientation parameters. The procedure was analogous to that used on images of the type III secretion complex (26), which required models from which to generate reference images.

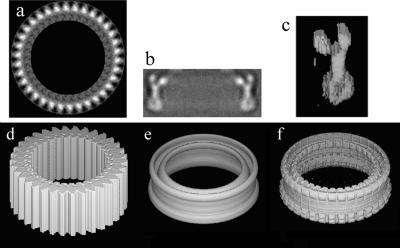

The models for the C ring were generated in a three-step process. First, we selected a good en face view of the C ring, which we determined by rotational autocorrelation to have 34-fold symmetry. After 34-fold averaging (Fig. 3a), we generated a mask that captured the main features in the averaged map. We extended the mask into 3D (Fig. 3d). Next, from the scaled average of the side view of the C ring (Fig. 3b), we generated a cylindrically averaged 3D map (Fig. 3e). Finally, we multiplied the 3D map made from the side view by the 3D mask made from the top view to generate a reasonable 3D model density (Fig. 3f) to use in the multireference alignment. Models for 32-, 33-, 35-, and 36-fold C rings were generated by extracting a single subunit (Fig. 3c) from the 34-fold model, placing it at a larger or smaller radius, and then applying the appropriate rotational symmetry. We did not search for the rare 31-,37-, and 38-fold C rings reported by Young et al. (51).

FIG. 3.

Steps in generating a reference for image sorting and alignment. (a) The rotationally averaged, 34-fold top view of a C ring. (b) Side view of the C ring, which is similar to that shown in Fig. 5, row B. (c) A single subunit carved out of the 3D reference shown in panel f. (d) A 3D mask that is made from the 2D image in panel a simply by extending the density along the axial direction. (e) A 3D map that is made by cylindrically symmetrizing the density shown in panel b. (f) The 3D reference model made by multiplying the mask in panel d by the map in panel e. This reference was used to generate reference projections for a multireference alignment.

Models for the M ring were produced from a cylindrically averaged 3D map of the M ring calculated from the 2D M-ring average. An azimuthal density variation was produced by adding an n-fold ring of ∼3-nm spheres of density, with each sphere centered at a radius of ∼12 to 13 nm depending on the symmetry being tested. We assumed that the 2D average corresponded to a ring having 26-fold symmetry (15, 35, 39). The remaining models from 21- to 28-fold symmetry were generated by interpolating the diameter of the initial 3D map appropriately and adding in a ring of spheres where the radius and number of the spheres were adjusted to correspond to the desired rotational symmetry.

We used the models to generate a large set of reference projections corresponding to different orientations as well as different symmetries. Since the HBB is elongated, it lies with its long axis approximately in the plane of the grid. Therefore, the reference projections are rotations about the long axis with limited out-of-plane tilt. We found the out-of-plane tilt to be between +14 and −14 degrees and therefore included reference projections in this range with 2-degree increments. In our initial alignments of the C ring, we tested projections with 19 angular increments about the long axis plus 15 increments of out-of-plane tilt, for a total of 285 reference projections per symmetry tested. We increased the number of projections about the long axis of the HBB to 23 during refinement of the C ring while keeping the out-of-plane tilt range the same; this brought the number of reference projections to 345 per symmetry tested. Reference projections of the M-ring model with 17 equal angular steps about the long axis were used. The projections in both cases were equally spaced over 360 degrees. All images were tested against all the projections of the corresponding model structure. Images were sorted into classes based on symmetry, and, at the same time, the orientational parameters to be used for reconstruction were determined. Note that the absolute hand of the structure was not known, since no tilting of the structure had been performed. The hands of the individual reconstructions were chosen to be internally consistent.

Confirmation of symmetry determinations.

Our results suggest that at least 15 combinations of M-ring and C-ring symmetry are possible. Two of these combinations have common subsymmetry; for the (nM,nC) = (24,36) class, there is a common 12-fold axis, and for the class (25,35), there is a common 5-fold axis. Only the 25,35 class contained enough images to generate a reasonable 3D map when applying only 5-fold subsymmetry. 3D reconstructions were carried out using the common 5-fold symmetry of images in which the C ring was 35-fold symmetric and the M ring was 25-fold symmetric. After a 5-fold symmetrization of the map, the symmetries of the component features of the M ring and the C ring were determined by autocorrelation using the OR 2 M command in SPIDER. An upper limit for the number of peaks to be found must be specified when using this command, and a value of 45 was chosen, which was well in excess of the expected values. The angular position is reported for each peak, allowing the size of the step between peaks to be determined.

Fitting of atomic models.

The docking of FliG (Protein Data Bank accession no. 1LKV) (5) was done by eye using the program O (16). Some rotation of the two domains of FliG relative to one another was necessary to achieve a good fit. The middle domain of FliG (5) was oriented to bring residues 170 and 166 within cross-linking distance (∼1 nm) of residues 117 and 120 on a neighboring subunit in accordance with the results of Lowder et al. (23).

RESULTS

The symmetry and structure of the C ring.

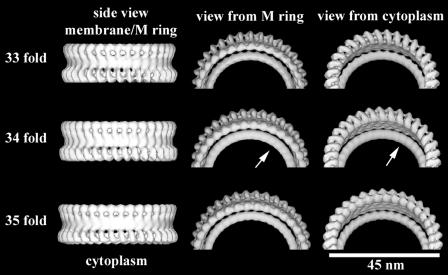

The gross morphology of the HBB is that of an elongated filamentous axial structure with sets of coaxial rings. Figure 4 shows a typical electron micrograph of a frozen-hydrated preparation of HBBs. Images of single C rings windowed from CTF-corrected micrographs were sorted according to their symmetry by using multireference alignment against projections of 3D models with symmetries from 32- to 36-fold (see Materials and Methods). The classes corresponding to 33-fold, 34-fold, and 35-fold symmetry had the most members. The numbers of individuals in each class (Table 1) followed a distribution very similar to the Gaussian distribution reported by Young et al. (51). The C rings in each class were averaged (Fig. 5). The diameters of the averaged C-ring images for each class increased with symmetry as expected (Fig. 5, left side) and agreed with the results of Young et al. The variance of the averages within each class was small, as would be expected if the members are identical particles (Fig. 5, right side). When the five class averages of different symmetries are aligned and averaged using the right half of the image of the C ring, the average from the aligned half is sharp and the variance is low, whereas the left-half image is blurred and has high variance (Fig. 5 row A). The classes corresponding to 33-, 34-, and 35-fold symmetry had sufficient numbers to generate 3D maps (Fig. 5 and 6). The 33-, 34-, and 35-fold reconstructions have maximum diameters of 46.5 nm, 47.8 nm, and 49.0 nm, respectively, and are 16.5 nm in height. The C rings all have a continuous spiral of density 7.0 nm in diameter around the cytoplasmic edge of the C ring. A continuous wall of density, 4.0 nm thick by 6.0 nm in height, connects the spiral to the upper two rings that lie adjacent to the M ring and membrane. These two rings are 3.4 nm thick in cross section. The outer ring is separated into clear lobes, whereas the inner ring is nearly featureless in all maps (Fig. 6). The reason for the difference in the appearances of the outer and inner rings is discussed below.

FIG. 4.

Electron micrograph of a frozen-hydrated preparation of hook-basal bodies extracted from a CW-locked mutant of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium. The arrows point to the hook-associated protein caps of three hook-basal body complexes. The L, P, M, and C rings are marked.

TABLE 1.

Numbers of images belonging to the various symmetry classes

| C-ring symmetry | No. of images with M-ring symmetry of:

|

Total for C ringsa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | ||

| 32 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 8 |

| 33 | 2 | 4 | 12 | 11 | 38 |

| 34 | 17 | 27 | 30 | 25 | 95 |

| 35 | 6 | 11 | 27 | 11 | 68 |

| 36 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 15 |

| Total for M ringsa | 33 | 47 | 90 | 55 | 225/224 |

The table gives the numbers of members in each symmetry class. The reason that the total for the M rings is different from the total for the C rings is that not all HBBs with M rings had C rings and not all C rings had useable M rings. All useable rings were included even though not all images had both M and C rings that were useable.

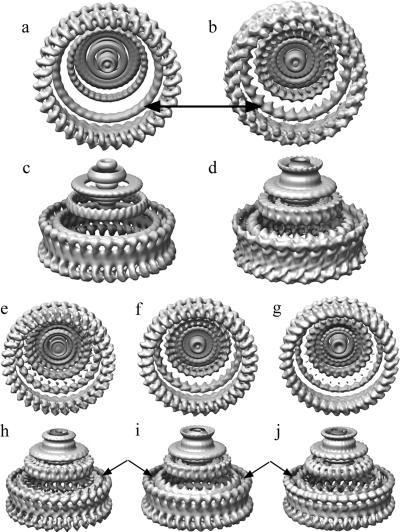

FIG. 6.

Surface views of the 3D maps of the C rings from the 33-, 34-, and 35-fold symmetry classes. (Left) Side view of the C rings. (Middle) Views looking down from the top. (Right) Views looking up from the bottom. Note that the all parts of the C ring have a strong periodicity except for the innermost ring (arrows in center row).

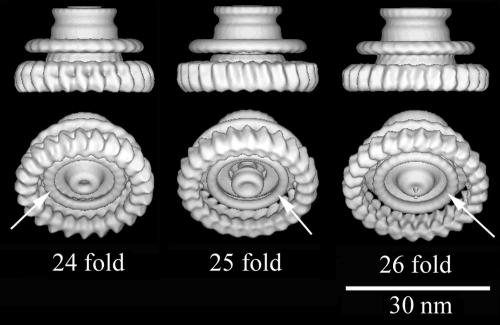

The symmetry and structure of the M ring.

We sorted and aligned the M-ring images by using multireference alignment against projections of 3D models having 21- to 28-fold symmetry. No examples of 21-, 22-, 27-, or 28-fold symmetry were identified. There were some images that fell into the 23-fold symmetry class. The average of these, however, corresponded to a highly tilted view of the structure (data not shown). No further processing of the 23-fold class was carried out. The class corresponding to 25-fold symmetry had the most members, with fewer but about equal numbers in the classes corresponding to 24-fold and 26-fold symmetry (Table 1). We found no obvious correlation between the symmetry of the M ring and the symmetry of the C ring.

There were sufficient numbers to allow reconstruction of 24-, 25-, and 26-fold M rings. The 24-fold M ring has the smallest diameter and the 26-fold M ring the largest (Fig. 7). The 24-, 25-, and 26-fold M rings have diameters of ∼28 nm, 29 nm, and 30 nm, respectively, and the S rings have diameters of 23.3 nm, 23.8 nm, and 24.3 nm, respectively. At the periphery of the cytoplasmic face of the M ring, there are lobes of density about 5.5 nm in radial depth, 5.5 nm in height, and spaced about 3.5 nm apart. Inside this ring of lobes lies a featureless ring of density 2.5 nm in cross section and centered at a radius of 7.8 nm (Fig. 7). At the center is a protrusion, which is seen in all M-ring averages and reconstructions although it is somewhat variable in appearance. The inner ring and protrusion may correspond to part of the export apparatus. The S ring and the sheath or collar, which enclose the rod, are relatively featureless, perhaps because of insufficient resolution. There is an indentation in the sheath where it meets the LP rings. The rod (not shown) is concealed within the S, P, and L rings; the morphological features of the rod are not accurate because the reconstruction process uses rotational, not helical, symmetry.

FIG. 7.

Surface views of the 3D maps of the M rings from the 24-, 25-, and 26-fold symmetry classes. The arrows point to an inner feature that might be a part of the export apparatus.

Reconstructions of motors with specific symmetry combinations.

Because we can separately classify C rings and M rings according to symmetry, we can select a subset of HBBs in which all the C rings from a single symmetry class (e.g., 35-fold) have M rings with a single symmetry (e.g., 25-fold symmetry). The images in these subsets were rewindowed from the micrographs with a larger window that allows both the C and M rings to be aligned and reconstructed within the same volume and keeps the same origin. Five such subsets had enough images to generate reconstructions.

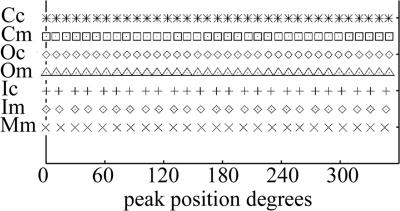

One subset had 35-fold C rings with 25-fold M rings. This class was chosen because both the M and C rings had fivefold symmetry in common, which allowed us to do fivefold averaging. Briefly, the images containing both the C ring and the M ring were aligned first to reference projections of only the 35-fold C-ring portion of the image and then to reference projections of only the 25-fold M ring. Two separate reconstructions were then carried out from the same subset of images, one using the parameters determined by alignment to the M-ring reference set and one using the parameters determined from alignment to the C-ring reference set. The resultant 3D maps were fivefold symmetrized. We determined the symmetry of the rings by summing serial axial sections from each map and then used rotational autocorrelation to discover the repeating features and hence the symmetry (Fig. 8). As expected, 25 equally spaced peaks were found for the M ring and 35 equally spaced peaks were found for outer features of the C ring. The inner ring of the C ring, the feature closest to the M ring, was found to have 25-fold symmetry, whereas the outer ring present in the same sections was found to have 35-fold symmetry. In all cases, either 25 or 35 equally spaced peaks were found; no other symmetries were detected by our protocol.

FIG. 8.

Plot of the angular positions of the peaks detected in the 3D map of the symmetry class having 35-fold C rings and 25-fold M rings. In the reconstruction only the common fivefold symmetry was enforced. Rotational autocorrelation was used to determine the symmetry (see Materials and Methods). Shown are the positions of peaks in the autocorrelation map of the M ring (M), C ring (C), outer ring of the C ring (O), and the inner ring of the C ring (I). The lowercase m or c refers to whether the reference used in alignment was the M-ring or C-ring reference. Independent of which reference was used, there are 35 peaks for the C ring except for its inner ring, which has 25 peaks as does the M ring.

We also aligned and reconstructed the other combinations of C-ring and M-ring symmetries: (33,25), (34,24), (34,25), and (34,26). The appearances of the C-ring and M-ring reconstructions are generally the same as when they are independently reconstructed (Fig. 6 and 7). In all cases, the inner ring of the C ring is featureless (Fig. 6 and 9a and c) in reconstructions when the C-ring symmetry is applied. When the M-ring symmetry is applied, the inner ring of the C ring is structured (Fig. 9b).

FIG. 9.

(a to d) Maps of the M and C rings made from the class of images having 25-fold M rings and 34-fold C rings. In panels a and c, the 34-fold C-ring symmetry is enforced on both the M and C rings. Note that the innermost lobe of the C ring (arrow) is weaker and relatively featureless. Note also that the M ring appears smaller because the misaveraged density is weaker. In panels b and d, the M-ring symmetry is enforced on both the M and C rings. Note that the features of the innermost ring of the C ring are strengthened and rest of the C ring features are lost. (e to g) Views from the bottom of the 3D map made from images having 33-fold C rings and 25-fold M rings, 34-fold C rings and 25-fold M rings, and 35-fold C rings and 25-fold M rings, respectively. (h to j) Side views of the maps in panels e to g. The inner ring of the C ring has had M-ring symmetry enforced. Note that there is an increasing upward tilt of the features in the inner ring of the C ring (arrows) as the C ring increases in diameter while the diameter of M ring remains unchanged.

DISCUSSION

An interesting aspect of the motor is whether the CW-locked motor differs in structure from that of the wild-type motor. The 2D averages shown in Fig. 5 show no discernible differences from comparable 2D averages from wild-type HBBs (Fig. 1 and 2 in reference 41). Such differences may be revealed in 3D maps, but that remains for the future.

To sort the images of the C rings according to their symmetry, we constructed a series of models with a symmetry range and subunit repeat based on parameters and symmetry distributions determined in previous studies (42, 51) and from analyzing the rare top views found within the data set. Thus, our 3D reference models had the right symmetries with correct dimensions. The same was not the case for the M ring, for which we had no such results. There was evidence that the M ring had approximately 26-fold symmetry (15, 39), but we had no way to tie M-ring symmetry to M-ring diameter. In our multireference alignment, the reference images vary by both symmetry and diameter, which are coupled. It was therefore possible that the computer programs were sorting based on M-ring diameter rather than on M-ring symmetry. It was an important confirmation that the M ring was found to be 25-fold symmetric when images in the (25,35) symmetry class were aligned using just the C-ring reference, followed by 5-fold symmetrization (see Materials and Methods). Moreover, the azimuthal features of the inner domain of the C ring were always strengthened when the symmetry and alignment we had determined for the M ring were applied to this feature. It is important to note that the average M ring has 25-fold symmetry, not 26-fold, even though 26-fold symmetry was assumed for the “average” starting model. We conclude that our algorithm does sort according to symmetry and not just diameter.

The M ring and FliG.

At a minimum, the complete M ring contains FliF and probably components of the export apparatus (10, 30). We find that the M-ring symmetry varies from 24-fold to 26-fold. This is similar to the variation in the symmetry of the type III secretion complex, which is a structure related to the basal body. In the type III complex, however, the variation is from 20- to 22-fold. A 3D reconstruction of the M ring has been published by Suzuki et al. (39) Using ammonium molybdate as a cryonegative stain, they examined M rings assembled from the expression of FliF or FliF and FliG in the absence of any other flagellar proteins such as the export proteins or FliM and FliN. They reported one symmetry class, which had 26-fold symmetry; this differs from our finding of 24-, 25-, and 26-fold symmetric classes. The diameter of the S ring in their map was 24 nm, which is the same as that in our map of the 26-fold-symmetric structure, but the M ring in their map had a diameter of 24 nm whereas the M ring in our map had a diameter of 30 nm. They suggest that the difference is likely due to the presence of FliG. Although Suzuki et al. generated maps of the FliF-FliG ring complex, the diameter increased only to about 26 nm, smaller than the diameter in our map. The M-ring structure determined by them is thinner than that in the wild-type structure (see Fig. 4 in reference 39), and little extra density can be seen in the reconstruction of their FliF-FliG M ring relative to that of the FliF-only M ring. They suggest that the discrepancy between the M-ring diameter that they measure and the diameter determined from wild-type motors is due to disorder in FliG, which is assembled in the absence of the stabilizing C ring. These conclusions are in line with earlier studies also comparing basal bodies with and without FliG. In that work, the loss of FliG led to a loss of density on the M ring (41). Thus, the evidence on hand argues that part of FliG occupies the outer rim and face of the M ring, whereas the remaining part, which can be disordered in the absence of the C ring, is likely a part of the C ring. One alternative model in which FliG is found entirely in the C ring (23), although not ruled out, seems much less likely to us.

The C ring.

We find that the symmetry of the bulk of the C ring varies from 32-fold to 36-fold. Young et al. (51), who generated basal bodies by overexpressing FliF, FliG, FliM, and FliN, found a range of symmetries from 31- to 38-fold, with a peak in the population between 34-and 35-fold. We also found the peak to lie between these two values. Because we had fewer particles, we did not look for 31-, 37-, and 38-fold classes, which Young et al. found to be rare.

Not all the features of the C ring possessed the same symmetry. Our results indicate that the inner lobe of the C ring, which lies closet to the M ring, has the symmetry of the M ring rather than that of the rest of the C ring. This could occur if the inner domain corresponded to a domain of either FliF or FliG. FliG binds to the cytoplasmic face of FliF. Because FliF is a transmembrane protein that nucleates the assembly of the other components of the flagellum, it defines the symmetry of the M ring. FliM is a component of the C ring and does not contribute to the M ring (12, 41). FliM interacts with FliG and FliN but not with FliF, and FliN does not interact with FliF. Therefore, the most plausible conclusion is that the inner domain of the C ring, which has the symmetry of the M ring, is a domain of FliG. Residues within the first 46 amino acids of FliG are required for binding to FliF (20) and thus are likely to be in the M ring. The C-terminal (motor) and middle domains of FliG are candidates that could make up part of the C ring.

If the C-terminal domain and possibly the middle domain of FliG are indeed part of the C ring, the key domains for torque generation and switching are all part of the C ring. This is intuitively more satisfying than having the motor domain of FliG in the M ring, because if the motor domain of FliG were in the M ring, how would the link between the M and C rings transmit to FliG the signal generated by the binding of phospho-CheY to FliM? Recall that this link must accommodate differences in the diameters of the C ring and M ring, differences due to the variation in symmetry. Clearly, a tight complex of the FliM with the motor domain of FliG in the C ring can provide a mechanical pathway for signal transmission.

There is evidence that FliG extends beyond the M ring. First, in images of negatively stained preparations, the M rings of HBBs containing FliG, but not FliM or FliN, appear much thicker than they do when the C ring is present (11, 12). This extra density extends into the region that would be occupied by the C ring were it present. Second, material can be seen connecting the outer rim, which we argue is the FliG portion of the M ring (39, 41), to the inner lobe in the C ring. Third, in one particular preparation of HBBs lacking C rings, a thin ring below the M ring at about the position of the inner lobe of the C ring was observed (D. G. Morgan, R. M. Macnab, N. R. Francis, and D. J. DeRosier, unpublished observation). The diameter of the ring was about the same as that of the M ring and smaller than that of the C ring. It is plausible that domains of FliG, freed from their interactions with FliM and FliN in the C ring, formed this extra ring. Thus, all the evidence taken together suggests that a portion of FliG contributes to features in the C ring.

The most obvious hypothesis is that the C-terminal or motor domain of FliG makes up the inner lobe of the C ring. This is one of two hypotheses proposed by Lowder et al. (23). The outer lobe would be a domain of FliM. Both FliG and FliM have been shown to interact weakly with the MotA-MotB complex (40), and this organization would permit both interactions.

The other hypothesis suggested by Lowder et al., and also by Brown et al. (5), places the motor domain of FliG in the outer lobe of the C ring, where it can interact both with FliM and with the MotA-MotB complex. The remainder of FliG makes up the inner lobe of the C ring. This arrangement of FliG domains puts FliM in contact with both the middle and C-terminal domains of FliG. The interaction of these two FliG domains with FliM is supported by mutational studies (27). The nearly invisible connection between the M and C rings in this model would be formed by residues from FliF.

Is the model of Brown et al. (5) consistent with the structural results we present; that is, can the two domains of FliG give rise to features with two different symmetries? If the C-terminal domain of FliG is tightly bound to FliM, it could give rise to the outer lobe of the C ring. It would appear as decoration of FliM but with partial occupancy. In this case the outer lobe would appear to have the symmetry of the C ring, but the density would be weaker than expected, reduced by ∼30% due to partial occupancy. The middle domain would be strung between the outer lobe of the C ring and the M ring, where it could, at least in principle, retain the symmetry of the M ring.

Cross-linking data favor the placement of the middle domain of FliG in the M ring. Four pairwise cysteine substitutions of FliG middle domain residues, which are 117C/166C, 120C/166C or 120C/170C, and 117C/170C, result in formation of dimers and higher oligomers in the presence of iodine, which promotes the formation of cystine (23). The pairs of cysteine residues are on opposite sides of the domain, 2.8 nm apart, where they cannot form intrasubunit cross-links. Instead, they form intersubunit cross-links leading to oligomerization. If there were a ring of 25 middle domains all within cross-linking distance, the radius of the ring containing these domains would be 13.5 nm (23), which is within the 14- to 15-nm outer radius of the M ring. In contrast, the innermost feature of the C ring is centered at a radius of 16.5 nm. At this radius, the cysteine residues would seem to be too far apart to be cross-linked. Lowder et al. (23), however, suggest that there might be sufficient flexibility in the structure that cross-linking is possible even if the middle domain lies at a radius of 16.5 nm. Again the most obvious hypothesis is that the middle domain of FliG lies in the M ring, although the alternative cannot be ruled out.

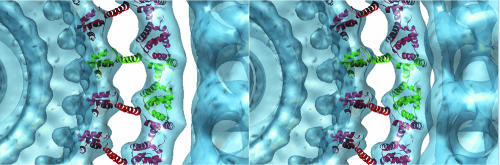

Possible dockings of atomic models into the 3D structure.

We have carried out a docking of the two domains of FliG into the map (Fig. 10). We chose to put the motor domain of FliG into the inner lobe of the C ring and the middle domain into the M ring. We placed the motor domain in a manner which fits the density without steric clashes while allowing the connection to the C-terminal end of helix E to be made without large rearrangements. The key charged residues are accessible for interactions with MotA if MotA were to bind between FliG subunits. We do not know how MotA and FliG will interact or what the interface will look like; the docking is shown to provide a visual framework for discussion. The middle domain is oriented to bring the cysteine pairs that form cross-links in the study of Lowder et al. (23) within reach of one another. The stretch of residues forming the alpha helix connecting the middle and C-terminal domains is long enough to span the gap between the inner ring of the C ring and the M ring without perturbing the alpha helix. We left it as an alpha helix, though it is unlikely to remain so, lacking some stabilizing contacts.

FIG. 10.

A stereo pair showing a possible docking of the two domains of FliG into the map from the class having 34-fold C rings and 25-fold M rings. The fit was performed by eye using the graphics program O (16). The Protein Data Bank accession number for this fragment of FliG is 1LKV (5). The motor domain of FliG is docked into the inner ring feature of the C ring, and the middle domain is docked into the M ring. One FliG subunit is shown in green and the rest in red.

There are no labeling data to tell us for sure which features of the C ring correspond to FliM or FliN. There are atomic models for the C-terminal domain of FliN from Thermotoga maritima and a homologue of FliN from the type III secretion system of P. syringae, HrcQBC (9). Docking the atomic models into our density does provide some clues about the possible organization of FliN. The structures of FliN and HrcQBC are very similar, but the former form is a dimer both in the crystal and in solution, whereas the latter is a tetramer. FliN from E. coli has been found to be a tetramer in solution (6). FliN is present in the C ring as a trimer or tetramer (6, 52). Two dimers from the atomic model for FliN can be fit in the lower spiral-shaped domain, forming a tetramer. The HrcQBC tetramer fits only in the thin walled domain separating the spiral domain at the bottom from the upper pair of lobes. The C-terminal region of FliM has homology to the C-terminal portion of FliN present in the crystal structure and is required for binding FliN (28, 44). FliM expressed alone forms inclusion bodies, but it can be recovered intact when expressed together with FliN (6, 31, 47). It is intriguing to imagine that in complex with FliM, FliN occurs as a trimer and the fourth partner in a possible tetramer is the N-terminal domain of FliM.

Paul and Blair (32) have performed cross-linking studies of FliN and propose that the disk of FliN composed of two FliN dimers seen in the FliN crystal structure (6) is most consistent with their results and that this disk would fit into the ring-like features at the cytoplasmic face of the C ring. The rings are features seen in projections (2D averages of the images). In 3D this ring-like feature is a spiral running around the cytoplasmic face of the C ring. The tetramers would have to be opened to form a lock washer structure, which would then fit into the spiral. In the absence of labels for FliN, we can at best narrow down the location of FliN to the lower two-thirds of the C ring.

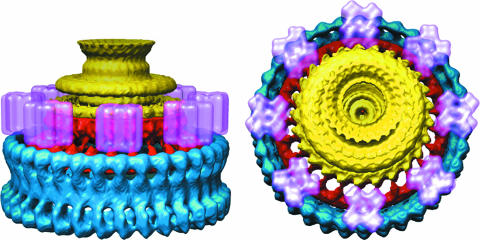

The MotA-MotB Complex, the putative stator.

Based on the work of Braun et al. (4)and Kojima and Blair, (21) we built a model to see how the rotor could interact with the stator. The four MotA subunits were each modeled as four transmembrane, four-helix bundles packed around two single transmembrane helices representing MotB. The cytoplasmic domain of MotA and the periplasmic domains of MotB were not included, since no structural information is available. The model was low-pass filtered at a resolution of 2 nm in our maps. Eight complexes could be easily placed around the rotor (Fig. 11), and perhaps three or four more complexes could be accommodated. The stator complex can fit easily into the space adjacent to the M ring in the membrane and above the two lobes of the C ring. At least two of the ∼35 subunits from the C ring and two of the ∼24 subunits from the M ring can be in contact with one MotA-MotB complex in this model.

FIG. 11.

Two views of the rotor with a model for the stator. The part of the rotor that we attribute to FliF is shown in yellow, the part we attribute to FliG is in red, and the part of the C ring that we hypothesize to contain FliM and FliN is in blue. The stator, which contains MotA and MotB, is in pink and is based on the model of Braun et al. (4). Only eight stators are shown, although more can be fit around the periphery of the rotor.

HBB symmetry and the angular step size of the motor.

Recently the angular step increment has been determined for motor rotation by using a chimera where the rotor proteins of E. coli are driven by the sodium-powered MotA/MotB homologues from Vibrio alginolyticus, PomA/PomB (36). The use of the sodium-powered stators allowed fine control of the sodium motive force across the membrane, which achieved slow stepping. The angular step size for rotation in the absence of CheY is 13.8°, which corresponds to ∼26 steps per rotation. Backwards steps, which occurred infrequently in the absence of switching, were about ∼−10.3°, which corresponds to 1/35 of a revolution. These two step sizes may be telling us that both the C-ring and M-ring symmetries are reflected in the operation of the motor.

We have shown that the symmetry and hence subunit composition in native flagellar rotors is variable and that variation in the C-ring symmetry is uncoupled or at best weakly coupled from variations in the M-ring symmetry. We have further evidence that FliG contributes to both the M and C ring and is therefore responsible for the linkage holding the two rings together.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tom Walz for allowing us to use his F20 electron microscope. We thank Beth Stroupe for a critical reading of the paper and David Blair, Richard Berry, Keiichi Namba, and Shahid Khan for useful discussions.

We acknowledge support from NIH grants R01GM35433 and P01GM26580 and support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute for D.R.T.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berg, H. C. 2003. The rotary motor of bacterial flagella. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72:19-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blair, D. F. 2003. Flagellar movement driven by proton translocation. FEBS Lett. 545:86-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blair, D. F., and H. C. Berg. 1990. The MotA protein of E. coli is a proton-conducting component of the flagellar motor. Cell 60:439-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun, T. F., L. Q. Al-Mawsawi, S. Kojima, and D. F. Blair. 2004. Arrangement of core membrane segments in the MotA/MotB proton-channel complex of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 43:35-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, P. N., C. P. Hill, and D. F. Blair. 2002. Crystal structure of the middle and C-terminal domains of the flagellar rotor protein FliG. EMBO J. 21:3225-3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, P. N., M. A. Mathews, L. A. Joss, C. P. Hill, and D. F. Blair. 2005. Crystal structure of the flagellar rotor protein FliN from Thermotoga maritima. J. Bacteriol. 187:2890-2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chun, S. Y., and J. S. Parkinson. 1988. Bacterial motility: membrane topology of the Escherichia coli MotB protein. Science 239:276-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dean, G. E., R. M. Macnab, J. Stader, P. Matsumura, and C. Burks. 1984. Gene sequence and predicted amino acid sequence of the MotA protein, a membrane-associated protein required for flagellar rotation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 159:991-999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fadouloglou, V. E., A. P. Tampakaki, N. M. Glykos, M. N. Bastaki, J. M. Hadden, S. E. Phillips, N. J. Panopoulos, and M. Kokkinidis. 2004. Structure of HrcQB-C, a conserved component of the bacterial type III secretion systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:70-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan, F., K. Ohnishi, N. R. Francis, and R. M. Macnab. 1997. The FliP and FliR proteins of Salmonella typhimurium, putative components of the type III flagellar export apparatus, are located in the flagellar basal body. Mol. Microbiol. 26:1035-1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francis, N. R., V. M. Irikura, S. Yamaguchi, D. J. DeRosier, and R. M. Macnab. 1992. Localization of the Salmonella typhimurium flagellar switch protein FliG to the cytoplasmic M-ring face of the basal body. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:6304-6308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Francis, N. R., G. E. Sosinsky, D. Thomas, and D. J. DeRosier. 1994. Isolation, characterization and structure of bacterial flagellar motors containing the switch complex. J. Mol. Biol. 235:1261-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frank, J., M. Radermacher, P. Penczek, J. Zhu, Y. Li, M. Ladjadj, and A. Leith. 1996. SPIDER and WEB: processing and visualization of images in 3D electron microscopy and related fields. J. Struct. Biol. 116:190-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irikura, V. M., M. Kihara, S. Yamaguchi, H. Sockett, and R. M. Macnab. 1993. Salmonella typhimurium fliG and fliN mutations causing defects in assembly, rotation, and switching of the flagellar motor. J. Bacteriol. 175:802-810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones, C. J., R. M. Macnab, H. Okino, and S. Aizawa. 1990. Stoichiometric analysis of the flagellar hook-(basal-body) complex of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Mol. Biol. 212:377-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones, T. A., J. Y. Zou, S. W. Cowan, and Kjeldgaard. 1991. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A 47:110-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan, S., M. Dapice, and T. S. Reese. 1988. Effects of mot gene expression on the structure of the flagellar motor. J. Mol. Biol. 202:575-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan, S., I. H. Khan, and T. S. Reese. 1991. New structural features of the flagellar base in Salmonella typhimurium revealed by rapid-freeze electron microscopy. J. Bacteriol. 173:2888-2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kihara, M., N. R. Francis, D. J. DeRosier, and R. M. Macnab. 1996. Analysis of a FliM-FliN flagellar switch fusion mutant of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 178:4582-4589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kihara, M., G. U. Miller, and R. M. Macnab. 2000. Deletion analysis of the flagellar switch protein FliG of Salmonella. J. Bacteriol. 182:3022-3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kojima, S., and D. F. Blair. 2004. Solubilization and purification of the MotA/MotB complex of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 43:26-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lloyd, S. A., H. Tang, X. Wang, S. Billings, and D. F. Blair. 1996. Torque generation in the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli: evidence of a direct role for FliG but not for FliM or FliN. J. Bacteriol. 178:223-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowder, B., M. D. Duyvesteyn, and D. F. Blair. 2005. FliG subunit arrangement in the flagellar rotor probed by targeted cross-linking. J. Bacteriol. 187:5640-5647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ludtke, S. J., P. R. Baldwin, and W. Chiu. 1999. EMAN: semiautomated software for high-resolution single-particle reconstructions. J. Struct. Biol. 128:82-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macnab, R. M. 2003. How bacteria assemble flagella. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:77-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marlovits, T. C., T. Kubori, A. Sukhan, D. R. Thomas, J. E. Galan, and V. M. Unger. 2004. Structural insights into the assembly of the type III secretion needle complex. Science 306:1040-1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marykwas, D. L., and H. C. Berg. 1996. A mutational analysis of the interaction between FliG and FliM, two components of the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 178:1289-1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathews, M. A., H. L. Tang, and D. F. Blair. 1998. Domain analysis of the FliM protein of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 180:5580-5590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mindell, J., and N. Grigorieff. 2003. Accurate determination of local defocus and specimen tilt in electron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 142:334-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohnishi, K., F. Fan, G. J. Schoenhals, M. Kihara, and R. M. Macnab. 1997. The FliO, FliP, FliQ, and FliR proteins of Salmonella typhimurium: putative components for flagellar assembly. J. Bacteriol. 179:6092-6099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oosawa, K., T. Ueno, and S. Aizawa. 1994. Overproduction of the bacterial flagellar switch proteins and their interactions with the MS ring complex in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 176:3683-3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paul, K., and D. F. Blair. 2006. Organization of FliN subunits in the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 188:2502-2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saxton, W. O. 1978. Computer techniques for image processing in electron microscopy. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 34.Sockett, H., S. Yamaguchi, M. Kihara, V. M. Irikura, and R. M. Macnab. 1992. Molecular analysis of the flagellar switch protein FliM of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 174:793-806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sosinsky, G. E., N. R. Francis, D. J. DeRosier, J. S. Wall, M. N. Simon, and J. Hainfeld. 1992. Mass determination and estimation of subunit stoichiometry of the bacterial hook-basal body flagellar complex of Salmonella typhimurium by scanning transmission electron microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:4801-4805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sowa, Y., A. D. Rowe, M. C. Leake, T. Yakushi, M. Homma, A. Ishijima, and R. M. Berry. 2005. Direct observation of steps in rotation of the bacterial flagellar motor Nature 437:916-919. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Stader, J., P. Matsumura, D. Vacante, G. E. Dean, and R. M. Macnab. 1986. Nucleotide sequence of the Escherichia coli motB gene and site-limited incorporation of its product into the cytoplasmic membrane. J. Bacteriol. 166:244-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stolz, B., and H. C. Berg. 1991. Evidence for interactions between MotA and MotB, torque-generating elements of the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 173:7033-7037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzuki, H., K. Yonekura, and K. Namba. 2004. Structure of the rotor of the bacterial flagellar motor revealed by electron cryomicroscopy and single-particle image analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 337:105-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang, H., T. F. Braun, and D. F. Blair. 1996. Motility protein complexes in the bacterial flagellar motor. J. Mol. Biol. 261:209-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas, D., D. G. Morgan, and D. J. DeRosier. 2001. Structures of bacterial flagellar motors from two FliF-FliG gene fusion mutants. J. Bacteriol. 183:6404-6412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas, D. R., D. G. Morgan, and D. J. DeRosier. 1999. Rotational symmetry of the C ring and a mechanism for the flagellar rotary motor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:10134-10139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Togashi, F., S. Yamaguchi, M. Kihara, S. I. Aizawa, and R. M. Macnab. 1997. An extreme clockwise switch bias mutation in fliG of Salmonella typhimurium and its suppression by slow-motile mutations in motA and motB. J. Bacteriol. 179:2994-3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toker, A. S., M. Kihara, and R. M. Macnab. 1996. Deletion analysis of the FliM flagellar switch protein of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 178:7069-7079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ueno, T., K. Oosawa, and S. Aizawa. 1992. M ring, S ring and proximal rod of the flagellar basal body of Salmonella typhimurium are composed of subunits of a single protein, FliF. J. Mol. Biol. 227:672-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vogler, A. P., M. Homma, V. M. Irikura, and R. M. Macnab. 1991. Salmonella typhimurium mutants defective in flagellar filament regrowth and sequence similarity of FliI to F0F1, vacuolar, and archaebacterial ATPase subunits. J. Bacteriol. 173:3564-3572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Welch, M., K. Oosawa, S. Aizawa, and M. Eisenbach. 1993. Phosphorylation-dependent binding of a signal molecule to the flagellar switch of bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:8787-8791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Welch, M., K. Oosawa, S. I. Aizawa, and M. Eisenbach. 1994. Effects of phosphorylation, Mg2+, and conformation of the chemotaxis protein CheY on its binding to the flagellar switch protein FliM. Biochemistry 33:10470-10476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamaguchi, S., S. Aizawa, M. Kihara, M. Isomura, C. J. Jones, and R. M. Macnab. 1986. Genetic evidence for a switching and energy-transducing complex in the flagellar motor of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 168:1172-1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yip, C. K., T. G. Kimbrough, H. B. Felise, M. Vuckovic, N. A. Thomas, R. A. Pfuetzner, E. A. Frey, B. B. Finlay, S. I. Miller, and N. C. Strynadka. 2005. Structural characterization of the molecular platform for type III secretion system assembly. Nature 435:702-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Young, H. S., H. Dang, Y. Lai, D. J. DeRosier, and S. Khan. 2003. Variable symmetry in Salmonella typhimurium flagellar motors. Biophys. J. 84:571-577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao, R., N. Pathak, H. Jaffe, T. S. Reese, and S. Khan. 1996. FliN is a major structural protein of the C-ring in the Salmonella typhimurium flagellar basal body. J. Mol. Biol. 261:195-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou, J., S. A. Lloyd, and D. F. Blair. 1998. Electrostatic interactions between rotor and stator in the bacterial flagellar motor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:6436-6441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]