Abstract

Human activities are altering many factors that determine the fundamental properties of ecological and social systems. Is sustainability a realistic goal in a world in which many key process controls are directionally changing? To address this issue, we integrate several disparate sources of theory to address sustainability in directionally changing social–ecological systems, apply this framework to climate-warming impacts in Interior Alaska, and describe a suite of policy strategies that emerge from these analyses. Climate warming in Interior Alaska has profoundly affected factors that influence landscape processes (climate regulation and disturbance spread) and natural hazards, but has only indirectly influenced ecosystem goods such as food, water, and wood that receive most management attention. Warming has reduced cultural services provided by ecosystems, leading to some of the few institutional responses that directly address the causes of climate warming, e.g., indigenous initiatives to the Arctic Council. Four broad policy strategies emerge: (i) enhancing human adaptability through learning and innovation in the context of changes occurring at multiple scales; (ii) increasing resilience by strengthening negative (stabilizing) feedbacks that buffer the system from change and increasing options for adaptation through biological, cultural, and economic diversity; (iii) reducing vulnerability by strengthening institutions that link the high-latitude impacts of climate warming to their low-latitude causes; and (iv) facilitating transformation to new, potentially more beneficial states by taking advantage of opportunities created by crisis. Each strategy provides societal benefits, and we suggest that all of them be pursued simultaneously.

Keywords: adaptability, Alaska, climate change, resilience, vulnerability

The world is undergoing rapid change in many of the factors that control the properties of ecosystems. In the last 50 years, humans have changed ecosystems more rapidly and extensively than during any comparable period of human history, with even more rapid and extensive changes projected for the next half century and beyond (1, 2). For example, human activities have substantially altered climate, the hydrologic cycle, biodiversity, land cover, the use of biological productivity, and the cycling of nitrogen at global scales (3). People have always profoundly influenced their environment (4). However, the recent increase in the magnitude and extent of these impacts raises serious challenges to sustaining earth's life support systems, the services that ecosystems provide to society (5). These ecosystem services contribute fundamentally to human well-being, i.e., the basic material needs for a good life, freedom and choice, good social relations, and personal security (6).

Given the importance and difficulty of fostering sustainability in a world with an uncertain future, many approaches are being explored (7–10). In this article, we integrate several of these approaches. We argue that, by understanding the linkages between global-scale changes and local-scale dynamics of human–environment interactions, we can recognize general sources of vulnerability, adaptability, and resilience that provide a scientific basis for broad policy strategies to enhance sustainability. We apply this framework to the impacts of climate warming on Alaska's boreal forest (11) and identify a suite of policy strategies that could contribute to sustainability. Alaska is a particularly appropriate place to apply this framework, because ecosystem services, which are key processes that mediate climate effects on society, are critical to the sustainability of traditional subsistence livelihoods and culture.

Integrating Conceptual Frameworks

Global–Local Linkages.

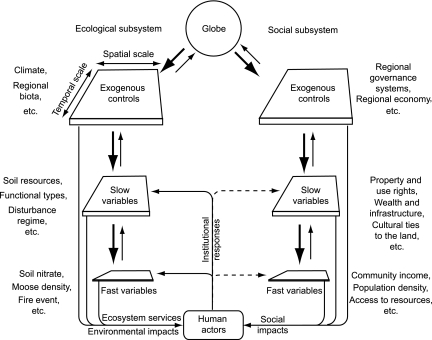

Ecological systems respond to a spectrum of controls that operate across a range of temporal and spatial scales and can be roughly grouped as exogenous controls, slow variables, and fast variables (Fig. 1). Exogenous controls (called state factors in the ecological literature) are factors that govern the properties of ecosystems but are not strongly influenced by the short-term, small-scale dynamics of a single forest stand or lake. Some exogenous controls, such as climate and regional biota, are regional in extent, whereas others, such as topography and geological substrate, vary more locally (12). Exogenous controls are often relatively constant over century and longer timescales. At the scale of an ecosystem or watershed, there are a few critical slow variables, i.e., parameters that strongly influence ecosystems but remain relatively constant over years to decades (13, 14). These slow variables include presence of particular functional types of plants and animals, disturbance regime, and the capacity of soils or sediments to provide water and nutrients (15). Slow variables in ecosystems, in turn, govern fast variables at the same spatial scale (e.g., moose density and individual fire events) that change on daily, seasonal, and interannual timescales. Conversely, human impacts on fast variables that persist over long time periods and in large areas can propagate upward to affect slow variables and even regional controls such as climate and regional biota that were once considered nearly constant parameters (2).

Fig. 1.

Diagram of a social–ecological system comprising an ecological subsystem (left) and a social subsystem (right), each with a spectrum of controls that operate across a range of temporal and spatial scales. Environmental impacts, ecosystem services, and social impacts govern the well-being of human actors, who affect ecological and social systems through a variety of institutions. Solid lines represent direct effects and dashed lines represent indirect effects.

Ecological and social systems affect one another so strongly that they are best viewed as a social–ecological system (i.e., a coupled human–environment system) (8, 10) (Fig. 1). Analogous to the ecological subsystem, the social subsystem can be viewed as composed of a spectrum of hierarchically interconnected exogenous, slow, and fast variables (16), ranging from global to local and linked by cross-scale interactions (17–20). At the subglobal scale, a predominant history, culture, economy, and governance system often characterizes broad regions or nation states (21). Regional controls sometimes persist for a long time and change primarily in response to changes that are global in extent (e.g., globalization of markets and finance institutions). Economic, political, and cultural differences between Alaska and Siberia, for example, have persisted through political upheavals and global economic trends. At other times, large-scale controls (e.g., economic systems) change quickly, as with the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. As in the biophysical system, a few slow social variables (e.g., wealth and infrastructure, property-and-use rights, and cultural ties to the land) are constrained by regional controls and interact with one another to shape fast social variables such as community income or population density. Both slow and fast social variables interact with ecological variables on multiple timescales. This interaction can produce ecological effects that are cumulatively large and extensive enough to affect biodiversity and climate at regional and larger scales (2).

Human–Environment Interactions.

Important advances in understanding the effects of climate change on social–ecological systems have occurred by focusing on processes that link ecological and social subsystems through their effects on human actors (Fig. 1) (17). These linkages include direct environmental impacts (7, 22) and ecosystem services, i.e., the benefits that society derives from ecosystems (1, 23). We use the categories of ecosystem services developed by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (1). The ecosystem services most readily incorporated into a socioeconomic framework are the goods (provisioning services) that are directly harvested and used by society (e.g., food, water, and fuel wood). In addition, there are supporting services (basic ecological processes that shape the structure and dynamics of ecosystems); regulating services such as climate and disturbance regulation that extend the spatial scale of social–ecological interactions from individual stands to landscapes; and cultural services that provide a sense of place and identity, aesthetic or spiritual benefits, and opportunities for recreation and tourism. The societal importance of ecosystem goods is well recognized because they are valued and traded in the market place. Other ecosystem services, especially supporting and cultural services that do not enter the marketplace, are often taken for granted by society and are particularly vulnerable to unintended degradation despite their societal value (24, 25).

Human actors (both individuals and groups) respond to social, environmental, and ecological impacts that they perceive through a complex web of institutions, i.e., the enduring regularities of human action in situations structured by rules, norms, and shared strategies (17, 26) (Fig. 1). Human actions, mediated by institutions, then affect slow and fast variables of both ecological and social systems. Institutions are a useful focus for analyzing societal responses to directional environmental changes because they affect politics by organizing and directing social behaviors (27). In addition, institutions are shaped by and structure history (27) by offering particular organizational opportunities, perpetuating values, and cultivating a set of actors within the political system (28, 29).

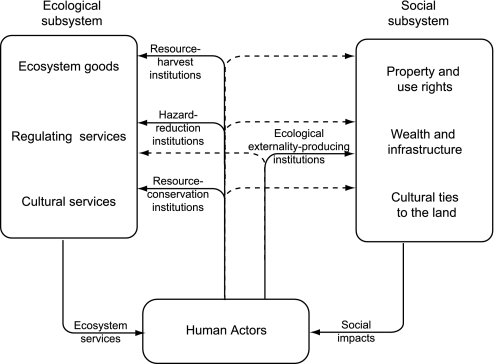

We recognize at least four types of institutions that differ in their ecological goals and consequences (26), and therefore, in their effects on ecosystems and responsiveness to environmental impacts (Fig. 2). (i) Resource-harvest institutions govern choices people make to manage the supply and harvest of ecosystem goods. These institutions respond most directly to short-term variations in conditions of resource supply and demand (i.e., to fast variables such as annual salmon escapement, instantaneous water supply rate to a community, or the price of fish). Resource-harvest institutions include choices made in agriculture and forestry, fish and wildlife management, and water management. They include formal governance systems, such as the regulatory regime of regional governments. They also include informal management systems, such as those governed by customary law and based on oral traditions, for example socially imposed harvest restrictions at times of low resource abundance (10). (ii) Resource-conservation institutions govern choices to conserve and protect ecosystem services, especially regulating and cultural services. Because of the generally larger temporal and spatial scales required to manage these services, resource-conservation institutions are more attuned to long-term conditions of slow variables. They include habitat and cultural protection measures and ecosystem conservation traditions and programs. Some of these institutions become formalized in response to perceptions of previous or potential ecosystem degradation. (iii) Hazard-reduction institutions govern choices that reduce the societal impacts of natural hazards such as wildfire, floods, and pest outbreaks. They seek cost-effective protection or coping strategies, given historical patterns of hazard occurrence. (iv) Ecological externality-producing institutions are a heterogeneous suite of rule sets that, in the process of pursuing social and economic development goals, have unintended side effects on ecosystems, creating externalities. These institutions include policies affecting credit and interest rates, international trade, war, industrial activities, construction of infrastructure (e.g., roads and cities), and extraction of nonrenewable resources. In the absence of externally imposed regulations or cross-linkage among institutions, such institutions are generally insensitive to the ecological impacts they produce.

Fig. 2.

Ecological institutions that influence ecosystem services. Solid lines represent direct effects and dashed lines represent indirect effects.

We now use the framework developed in this section as a basis for understanding the changes occurring in interior Alaska in response to changes in a single exogenous control, the warming of climate.

Social–Ecological Response to Warming in Interior Alaska

Climate warming has triggered pronounced ecological and social change in interior Alaska. Since 1950, air temperature has increased by 0.4°C per decade, the growing season has lengthened by 2.6 days per decade, and permafrost (permanently frozen ground) has warmed by 0.5°C per decade, with projections that air temperature will increase more rapidly during the 21st century (0.4–0.7°C per decade) (11, 30).

Warming has affected ecosystem and population processes (i.e., supporting services) primarily through changes in the hydrologic cycle that alter two categories of slow variables, soil resources and the disturbance regime. As climate warms, increased evapotranspiration, combined with a modest increase in precipitation, has lowered regional water tables, causing soil drying (30), reductions in tree growth (31), increases in severity and extent of wildland fire (32), and bark beetle outbreaks, in part because warming reduced the length of the beetle's life cycle from two years to one, causing a threshold shift in the balance between the tree and the insect (33). Warming and disturbance foster other disturbances. Insect outbreaks increase the probability of fire and salvage logging. Permafrost thaw occurs more rapidly after fire because loss by combustion of the insulative organic mat makes permafrost temperature more responsive to warming air temperature. In lowlands, permafrost thaw creates ponds and wetlands, whereas in uplands it amplifies soil drying through improved vertical draining. The large predicted increases in permafrost thaw (30) would profoundly alter the hydrologic controls over ecosystem processes and challenge ecological resilience.

Climate warming affects social slow variables through both direct environmental impacts and changes in ecosystem services. In interior Alaska, buildings and oil pipelines are generally built with a sufficient safety margin, with the result that permafrost thaw has had modest impacts on infrastructure, whereas in Siberia, where safety margins are smaller, permafrost thaw has contributed to catastrophic failure of roads and pipelines, causing oil spills and erosion that have substantially impacted the ecosystem services on which local reindeer herders and fishermen depend (34). This fact illustrates the importance of regional variation in exogenous social controls and institutional responses when assessing societal impacts of climate warming. Climate warming directly reduces access and use of lands surrounding villages in interior Alaska by reducing summer river levels and slowing the rate at which river ice freezes to a thickness that supports winter travel by snow machine. Thin ice reduces the safety of travel over ice . Warming also reduces access because the more extensive fires destroy trapping cabins and topple trees, making overland travel more hazardous and difficult (35). Cues that were traditionally used to predict weather and assess the safety of travel over ice are now less predictive, eroding cultural ties to the land (36).

The impacts of climate warming on Alaska depend on a hierarchy of interactions among processes occurring at different scales (19, 37). Warming is largely the product of global-scale processes, including anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases, but is amplified at high latitudes as reflective sea ice, glaciers, and snow cover are replaced by heat-absorbing water, land, and forests (38). The impacts of warming on fire regime depend on legacies of human activities, such as the active burning of forests by early 20th century gold miners, which increased the proportion of less flammable early successional deciduous forests, in contrast to current fire suppression, which increases the continuity of late successional flammable fuels (39). In summary, understanding the warming effects on a societally important property such as fire risk depends on processes occurring at many temporal and spatial scales.

Institutional Responses to Climate Warming

Most formal state and federal institutions that manage ecosystem services in interior Alaska address a single category of fast variable (e.g., abundances of fish and game, or timber yield) rather than the supporting and regulating services (i.e., the critical slow variables) that are more fundamentally affected by warming. Fish and wildlife managers, for example, focus almost exclusively on the population consequences of variations in predators and human harvest and have little time, authority, or funding to address the consequences of warming. Informal institutions (e.g., subsistence traditions) that govern hunter behavior also focus primarily on population variability in fish and game populations in the context of community well-being and cultural identity. In summary, resource-harvest institutions in interior Alaska, and perhaps more broadly, are generally poorly designed and ill-equipped to manage for climate change and other directionally changing slow variables.

Resource-conservation institutions focused on cultural services have been proactive in addressing the causes of climate warming in interior Alaska. Indigenous Alaskans generally acknowledge that climate is warming and view human intervention as an important contributing factor. Their observations provided some of the first and most extensive evidence for widespread warming effects on supporting services (e.g., altered hydrology and abundances of key indicators of ecosystem functioning) and provisioning services (subsistence resources) in interior Alaska (30, 40). These groups initiated interactions with the scientific community to become more informed about potential causes of these patterns (35). Having made similar observations (40), indigenous peoples from across the circumpolar north have joined forces in the Inuit Circumpolar Conference, and as members of the Arctic Council (an international body that represents governments and indigenous peoples of all arctic nations) to raise international awareness of the cultural consequences of anthropogenic contributions to global warming, thus forming new coalitions that function at the social-state and international levels, i.e., the same scale as the anthropogenic contributions to the problem (41). The effectiveness of these coalitions in influencing anthropogenic contributions to climate warming remains to be seen. Wilderness-focused nongovernmental organizations represent another stakeholder group that seeks to link the causes of global warming to their high-latitude consequences. Both indigenous groups and wilderness-focused nongovernmental organizations directly facilitate cross-scale interactions by linking local groups with national and international lobbying efforts. Federal agencies such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Park Service, which are tasked with managing species and cultural resources, respectively, have placed greater emphasis on climate-change research in interior Alaska than have many other management agencies. They have designed ecological monitoring programs to document ecological impacts of climate change and begun managing wildfire regimes in ways that consider the long-term impacts on fuel loads. These nongovernmental organizations and agencies are more likely to respond to slow variables and to foster cross-scale linkages than are agencies tasked with managing ecosystem goods.

Hazard (wildfire)-reduction institutions in Alaska deal with processes that are demonstrably linked to climate warming. However, fire managers focus less on long-term climate trends than on short-term controls over fire regime, such as fuel management, values at risk, and availability of trained personnel and equipment. In addition, public representatives (i.e., Fairbanks North Star Borough Assembly Commission) have responded to recent increases in fire extent in interior Alaska by demanding more fire suppression, which is likely to increase the continuity of late successional flammable fuels near communities (42). Although innovative fire managers are raising new perspectives, the institutional response to fire has historically exacerbated rather than reduced the problems associated with climate warming. Similar patterns have been observed elsewhere with respect to managing hazards such as fire, floods, and insect outbreaks (43).

Institutions that manage climate-sensitive infrastructure generally account for climate-change projections and design infrastructure accordingly. For example, road and building construction on permafrost terrain in interior Alaska increasingly uses new technology or larger safety factors to reduce heat transfer to permafrost, thereby minimizing the vulnerability of infrastructure to permafrost thaw. Other ecological externality-producing institutions abide by environmental regulations but generally do not consider climate change in actions that have environmental consequences. Plans for urban expansion, privatization of lands for recreational cabins, and expansion of the road system in interior Alaska, for example, generally ignore the resulting increase in human ignitions (39) and the likelihood that future fires will be larger and more severe.

Most institutional responses to changes in ecosystem services in interior Alaska address a single fast variable (e.g., maximum sustained yield of moose or effective fire suppression) with less attention to linkages to the supporting services that govern long-term trends or unexpected changes in the managed variable. Managing for moose without managing for the effects of fire on moose habitat has limited long-term effectiveness. Resource management is frequently partitioned in ways that discourage rather than encourage the management of linkages among ecosystem services. This tendency of “stove-piped governance and institutions” and their organizational structures to manage a single fast variable without considering secondary effects on other components of the social–ecological system is a widespread phenomenon that reduces the capacity of existing institutions to account for complex social–ecological changes.

Identifying Policy Strategies

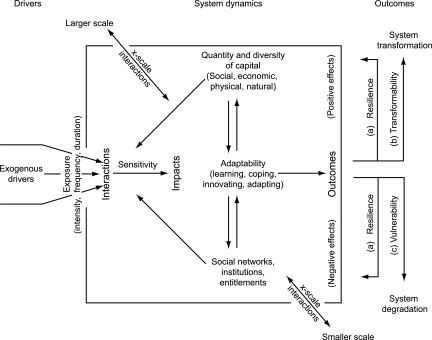

The previous sections demonstrate that climate warming has had pervasive effects on social–ecological processes in interior Alaska, but that a cohesive policy response has not yet been developed. Recent advances in the emerging science of sustainability (1, 5, 8, 9) now provide a suite of at least four policy strategies that could be integrated to address the consequences of large directional changes. These approaches differ in their presumed mechanisms (Table 1) and have developed somewhat independently (44) but are being increasingly integrated in their application (7, 45). Here we briefly summarize the interrelationships and underlying mechanisms of these four strategies (Fig. 3) and apply them to the effects of climate warming in interior Alaska to illustrate their potential as a framework for an integrated policy response.

Table 1.

Assumptions of frameworks addressing long-term human well-being

| Framework | Assumed change in exogenous controls | Nature of mechanisms emphasized | Other approaches often incorporated | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptability | None | Learning and innovation | None | 7, 19 |

| Resilience | Known or unknown | Within-system feedbacks, social–ecological diversity | Adaptability | 9, 56 |

| Vulnerability | Known | System sensitivity to drivers | Adaptability, resilience, transformability | 7, 45 |

| Transformability | Directional | Permanent change | Adaptability | 10, 56 |

Fig. 3.

Conceptual framework linking human adaptability, vulnerability, resilience, and transformability.

The consequences (outcomes) of climate warming for interior Alaska depend on the exposure of the system (e.g., household, community, or nation) to interacting drivers of change (e.g., climate warming and oil prices) and on internal system dynamics that govern the sensitivity and adaptability of the system to these interacting drivers (Fig. 3) (7). The broad categories of outcome are persistence of the fundamental properties of the existing system; active transformation of the system to a new, potentially more desirable state; or passive degradation of the system to a less favorable state as a result of system failure to adapt or transform. Adaptability, in turn, depends on the amount and diversity of social, economic, physical, and natural capital and on the social networks, institutions, and entitlements that govern how this capital is distributed and used. System response also depends on effectiveness of cross-scale linkages to changes occurring at other temporal and spatial scales. The relative likelihood of alternative outcomes depends on the net effects of human adaptability, resilience, vulnerability, and transformability (defined below), each of which is policy-sensitive. We suggest four broad policy strategies.

Foster Human Adaptability.

Human adaptability is the capacity of actors (both individuals and groups) in a system to respond to, create, and shape variability and change in the state of the system (7, 10, 19, 46). Because of the central role of human actions in social–ecological dynamics (Fig. 1), human adaptability is fundamental to all approaches to sustainability science, particularly under conditions of surprise, which will likely increase under global environmental change (47). Adaptability can be enhanced through policies that promote learning and innovation and the capacity to adjust to changes occurring at multiple scales.

Many types of learning could enhance adaptive capacity in interior Alaska. For example, enhanced educational and training opportunities, especially for disadvantaged segments of society, increase social capital and therefore society's capacity to adapt (7). Alaska's relatively well developed cyberinfrastructure for distance delivery and history of knowledge sharing between western scientists and traditional knowledge holders provides opportunities for different stakeholder groups to learn, in culturally appropriate ways, how climate warming will likely affect them. At a more technical level, the integration of science and technology with local understanding could provide novel solutions (e.g., heat pumps that prevent permafrost thaw or the introduction of community gardens to regions that were previously too cold for gardening), often involving substitutions among financial, natural, physical, and human capital through time (8, 48). Development of plausible scenarios of future trajectories of entire suites of ecosystem services and environmental impacts is feasible and could interconnect some of the stove-piped institutions to allow more informed and comprehensive planning. Active experimentation in management and governance (i.e., adaptive management and adaptive governance, respectively) provide opportunities for social learning to foster adjustments to change (49–51), for example, managing a gradually evolving arctic fishery that will likely develop as the Arctic Ocean becomes increasingly ice-free and fish-rich (52). Active participation and interaction of multiple stakeholder groups is critical to effective learning, coping, innovating, and adapting and must be nested across organizational scales through the development of flexible systems of adaptive governance (50, 53). Adaptation will be most successful if it is compatible with and supported by changes occurring at other scales (19, 54). Changes in management of commercial and subsistence salmon fisheries in Alaska, for example, are most likely to be successful if planned with the expectation that farmed salmon produced in other countries will continue to provide a cheap alternative to Alaskan salmon (55).

Enhance Resilience.

Resilience is the capacity of a social–ecological system to absorb shocks or perturbations and still retain its fundamental function, structure, identity, and feedbacks, often as a result of adaptive adjustment to changing conditions (9, 56, 57). Resilience theory addresses the capacity of a social–ecological system to persist without addressing human values. Many undesirable states, such as polluted, degraded landscapes or dictatorships may be quite resilient, so resilience is not always socially desirable. Resilience can be enhanced by strengthening negative (i.e., stabilizing) feedbacks that buffer the system against change; fostering ecological, cultural, institutional, and economic diversity; and fostering adaptability (see above) (9, 10).

Subsistence hunting and fishing are major components of the economy and diet of rural Alaskan communities (58). Subsistence depends on harvest of fish and game that are public goods rather than owned by private individuals or government. Extensive intercomparisons of systems that manage these common-pool resources suggest that a well developed system of institutional negative feedbacks increases the likelihood of sustaining these resources (26, 50). These institutional analyses suggest that stabilizing feedbacks in Alaska could be strengthened through greater involvement of local users in the management, monitoring, and enforcement of subsistence-resource use. Game management to meet alternative social goals (e.g., equal access by local subsistence users and nonlocal sport hunters) requires a different set of socially imposed negative feedbacks to prevent overharvest.

Institutions that foster biological, cultural, institutional, and economic diversity increase the likelihood that important functional components of the current social–ecological system will persist (59). Although interior Alaska has a low species diversity, which is typical of high latitudes, it has a high landscape diversity maintained by wildfire (60). By retaining wildfire as an important landscape process, Alaska has the opportunity to retain this source of landscape diversity in ways that are no longer feasible in more urbanized regions. In contrast to its ecology, Alaska's economy has low diversity and is dominated by extraction of one nonrenewable resource (oil). Diversification of the economy could enhance Alaska's resilience to economic surprises such as pipeline corrosion that shuts down oilfields (52).

Reduce Vulnerability.

Vulnerability is the degree to which a system is likely to experience harm because of exposure to a specified hazard or stress (7, 45). Vulnerability theory is rooted in socioeconomic studies of impacts of events (e.g., floods or wars) or stresses (e.g., chronic food shortage) on social systems. It deliberately addresses human values such as equity and is oriented toward providing practical outcomes. Vulnerability can be reduced by reducing the exposure to stress; reducing the sensitivity of important response variables to changes in these controls; and/or increasing adaptability and resilience to cope with and adapt to stress (see above; Fig. 3) (7, 45).

Reducing the anthropogenic contribution to climate warming is the key to mitigating climate change-related vulnerability in interior Alaska. This mitigation is challenging because anthropogenic forcing of climate change is primarily the result of greenhouse gas emissions at lower latitudes where human demographic and technological change and political power are concentrated. Because the anthropogenic source of change is dispersed globally, it cannot be reversed by actions taken solely at high latitudes where climate change and its ecological and societal impacts are most pronounced (22). If vulnerability to climate change is to be reduced, strong actions must be initiated promptly, given the long time lag between changes in carbon emissions and reductions in atmospheric concentrations (61). The most logical approaches to mitigating climate change are to strengthen international institutions such as treaties (e.g., Kyoto Protocol) and market mechanisms (e.g., carbon credits) that address causes and consequences at the same scale, and to foster cross-scale linkages among institutions, for example between locally based arctic indigenous groups and the Arctic Council, as described earlier. The United States accounts for 25% of anthropogenic CO2 emissions (and arctic nations as a group account for 40% of these emissions), so increased responsiveness of arctic nations to arctic warming could substantially reduce climate forcing from emissions of greenhouse gases.

Making the system less sensitive to stressors can also reduce vulnerability (7). Actions can be taken to reduce the sensitivity of specific processes to climate warming, for example, the use of passive heat pumps to protect pipeline integrity from permafrost warming or mechanical fuel reduction programs to reduce wildland fire risk to communities. Some ecological responses to warming reduce system sensitivity to warming (e.g., the increased proportion of less flammable early successional forests as climate-driven fires become more extensive). Other climate-warming effects augment sensitivity to warming, for example, the increased likelihood of winter travel fatalities as river and lake ice become thinner and fail to support snow machines. In general, the options to reduce vulnerability to climate warming in interior Alaska by reducing climate sensitivity appear relatively limited, except through human adaptation, for example, by relocating villages threatened by coastal erosion.

Enhance Transformability.

Transformability is the capacity to create a fundamentally new system with different characteristics (51, 56). If the current state of a system is undesirable, fostering transformability through human adaptation allows a shift to a different, potentially more beneficial state. The distinction between social–ecological resilience through modification of a given system and transformation to a new state is often fuzzy and depends on the properties and stakeholder groups considered (56). Even though total collapse seldom occurs (4, 62), active transformations of important components of a system are frequent (e.g., from an extractive to a tourist-based economy). In general, diversity and adaptability, which are key components of resilience, also enhance transformability because they provide the seeds for a new beginning and the adaptive capacity to take advantage of these seeds (10). Transformations (including socially beneficial transitions) are often triggered by crisis, so the capacity to recognize opportunities associated with crisis contributes to transformability (9, 10). For example, the global increase in oil prices threatens the viability of many rural communities in interior Alaska that depend on diesel fuel for power and heat. This crisis increases the economic feasibility of switching to biomass fuels, which could simultaneously provide wage income within the community and reduce warming-induced wildfire risk to communities (63).

Conclusions

Despite the substantial challenge of sustaining the beneficial attributes of complex social–ecological systems in the face of multiple large-scale directional changes, the dynamics of these systems suggest at least four general policy strategies that could meet this challenge. The greatest opportunities appear to include (i) fostering human adaptability through learning and innovation within the context of changes occurring at other scales; (ii) enhancing resilience by strengthening negative feedbacks that enhance the capacity to deal with change and surprise and fostering biological, cultural, and economic diversity; (iii) reducing vulnerability by reducing the anthropogenic contribution to climate warming (through reduced emissions of greenhouse gases) or reducing the sensitivity of vulnerable populations; and (iv) facilitating transformation under circumstances where components of the current system are no longer desirable. Implementation of these strategies in a concurrent and complementary fashion could be most effective. Although strong directional changes in climate generate challenges and opportunities that are specific to Alaska, we suggest that the general policy strategies described here should be broadly applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. R. Carpenter, W. C. Clark, E. Ostrom, C. Folke, P. A. Matson, B. L. Turner II, and B. Walker for constructively critical reviews. We acknowledge the Resilience and Adaptation Program, Integrative Graduate Education and Research Training Program (National Science Foundation Grant 0114423); the Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (National Science Foundation Grant 0346770); the Bonanza Creek Long-Term Ecological Research Program (funded jointly by National Science Foundation Division of Environmental Biology Grant DEB-0423442 and U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station Grant PNW01-JV11261952-231); and the Human-Fire Interactions Project (National Science Foundation Grant 0328282) for their financial support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See accompanying Profile on page 16634.

References

- 1.Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Washington, DC: Island; 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steffen WL, Sanderson A, Tyson PD, Jäger J, Matson PA, Moore B, III, Oldfield F, Richardson K, Schellnhuber HJ, Turner BL II, Wasson RJ. New York: Springer; 2004. Global Change and the Earth System: A Planet under Pressure. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vitousek PM, Mooney HA, Lubchenco J, Melillo JM. Science. 1997;277:494–499. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner BL II, McCandless SR. In: Earth System Analysis for Sustainability. Clark WC, Crutzen P, Schellnhuber HJ, editors. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2004. pp. 227–243. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Research Council. Washington, DC: Natl Acad Press; 1999. Our Common Journey: A Transition Toward Sustainability. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dasgupta P. Oxford: Oxford Univ Press; 2001. Human Well-Being and the Natural Environment. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turner BL II, Kasperson RE, Matson PA, McCarthy JJ, Corell RW, Christensen L, Eckley N, Kasperson JX, Luers A, Martello ML, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8074–8079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1231335100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark WC, Dickson NM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8059–8061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1231333100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunderson LH, Holling CS. Washington, DC: Island; 2002. Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berkes F, Colding J, Folke C. Navigating Social–Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapin FS III, Oswood MW, Van Cleve K, Viereck LA, Verbyla DL. New York: Oxford Univ Press; 2006. Alaska's Changing Boreal Forest. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amundson R, Jenny H. Bioscience. 1997;47:536–543. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carpenter SR, Turner MG. Ecosystems. 2000;3:495–497. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gunderson LH, Pritchard L. Washington, DC: Island; 2002. Resilience and the Behavior of Large-Scale Ecosystems. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chapin FS III, Matson PA, Mooney HA. New York: Springer; 2002. Principles of Terrestrial Ecosystem Ecology. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Straussfogel D. Econ Geogr. 1997;73:118–130. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young OR. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2002. The Institutional Dimensions of Environmental Change: Fit, Interplay, and Scale. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ostrom E. In: Theories of the Policy Processes. Sabatier PA, editor. Boulder, CO: Westview; 1999. pp. 35–71. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adger WN, Arnell NW, Tompkins EL. Glob Environ Change. 2005;15:77–86. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cash DW, Moser SC. Glob Environ Change. 2000;10:109–120. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chase-Dunn C. J Interam Stud World Aff. 2000;42:109–126. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCarthy JJ, Martello ML, Corell R, Selin NE, Fox S, Hovelsrud-Broda G, Mathiesen SD, Polsky C, Selin H, Tyler NJC. In: Arctic Climate Impact Assessment. Symon C, Arris L, Heal B, editors. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2005. pp. 945–988. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daily GC. Washington, DC: Island; 1997. Nature's Services: Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosystems. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costanza R, d'Arge R, de Groot R, Farber S, Grasso M, Hannon B, Limburg K, Naeem S, O'Neill RV, Paruelo J, et al. Nature. 1997;387:253–260. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daily GC, Soderqvist T, Aniyar S, Arrow K, Dasgupta P, Ehrlich PR, Folke C, Jansson A-M, Jansson B-O, Kautsky N, et al. Science. 2000;289:395–396. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5478.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ostrom E. Princeton: Princeton Univ Press; 2005. Understanding Institutional Diversity. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Putnam R. Princeton: Princeton Univ Press; 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lovecraft AL. Admin Theor Praxis. 2004;26:383–407. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brosius P. Curr Anthropol. 1999;40:277–309. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hinzman LD, Bettez ND, Bolton WR, Chapin FS III, Dyurgerov MB, Fastie CL, Griffith B, Hollister RD, Hope A, Huntington HP, et al. Clim Change. 2005;72:251–298. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barber VA, Juday GP, Finney BP. Nature. 2000;405:668–673. doi: 10.1038/35015049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kasischke ES, Turetsky MR. Geophys Res Lett 33. 2006 doi: 10.1029/2006gl025677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berg EE, Henry JD, Fastie CL, De Volder AD, Matsuoka S. For Ecol Manage. 2006;227:219–232. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forbes B, Fresco N, Shvidenko A, Danell K, Chapin FS., III Ambio. 2004;33:377–382. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447-33.6.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huntington HP, Trainor SF, Natcher DC, Huntington O, DeWilde L, Chapin FS., III Ecol Soc 11. 2006 Available at www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss1/art40. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berkes F. The Earth Is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change. In: Krupnik I, Jolly D, editors. Fairbanks, AK: Arctic Research Consortium of the United States; 2002. pp. 335–349. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peterson GD. Clim Change. 2000;44:291–309. [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGuire AD, Chapin FS, III, Walsh JE, Wirth C. Annu Rev Environ Resources 31. 2006 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 39.DeWilde L, Chapin FS., III Ecosystems. 2006 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krupnik I, Jolly D, editors. Fairbanks, AK: Arctic Research Consortium of the United States; 2002. The Earth is Faster Now: Indigenous Observations of Arctic Environmental Change. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stefansson Arctic Institute. Arctic Human Development Report. Iceland: SAI, Akureyri; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chapin FS III, Rupp TS, Starfield AM, DeWilde L, Zavaleta ES, Fresco N, McGuire AD. Front Ecol Environ. 2003;1:255–261. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holling CS, Meffe GK. Conserv Biol. 1996;10:328–337. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Janssen MA, Schoon ML, Ke W, Borner K. Glob Environ Change. 2006;16:240–252. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kasperson RE, Dow K, Archer ERM, Caceres D, Downing TE, Elmqvist T, Eriksen S, Folke C, Han G, Iyengar K, et al. Vol 1. Washington, DC: Island; 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being; pp. 143–164. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ford JD, Smit B. Arctic. 2004;57:389–400. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schneider S, Turner BL, II, Garriga HM. J Risk Res. 1998;1:165–185. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arrow K, Goulder L, Dasgupta P, Daily G, Ehrlich P, Heal G, Levin S, Mäler KG, Schneider S, Starrett D, Walker B. J Econ Perspect. 2004;18:147–172. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walters CJ. New York: McGraw–Hill; 1986. Adaptive Management of Renewable Resources. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dietz T, Ostrom E, Stern PC. Science. 2003;302:1907–1912. doi: 10.1126/science.1091015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carpenter SR, Folke C. Trends Ecol Evol. 2006;21:309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chapin FS III, Hoel M, Carpenter SR, Lubchenco J, Walker B, Callaghan TV, Folke C, Levin S, Mäler KG, Nilsson C, et al. Ambio. 2006;35:198–202. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447(2006)35[198:braatm]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Folke C, Hahn T, Olsson P, Norberg J. Annu Rev Environ Resources. 2005;30:441–473. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berkes F, Bankes N, Marschke M, Armitage D, Clark D. In: Breaking Ice: Renewable Resource and Ocean Management in the Canadian North. Berkes F, Huebert R, Fast H, Manseau M, Diduck A, editors. Calgary, AB, Canada: Univ of Calgary Press; 2005. pp. 225–247. [Google Scholar]

- 55.National Research Council. Developing a Research and Restoration Plan for Arctic-Yukon-Kuskokwim (Western Alaska) Salmon. Washington, DC: Natl Acad Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Walker B, Holling CS, Carpenter SR, Kinzig A. Ecol Soc 9. 2004 Available at www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss2/art5. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Folke C. Glob Environ Change. 2006;16:253–267. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Magdanz JS, Utermohle CJ, Wolfe RJ. The Production and Distribution of Wild Food in Wales and Deering, Alaska. Division of Subsistence, Kotzebue, AK: Alaska Department of Fish and Game; 2002. Technical Paper 259. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Elmqvist T, Folke C, Nyström M, Peterson G, Bengtsson J, Walker B, Norberg J. Front Ecol Environ. 2003;1:488–494. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chapin FS III, Danell K. In: Global Biodiversity in a Changing Environment: Scenarios for the 21st Century. Chapin FS III, Sala OE, Huber-Sannwald E, editors. New York: Springer; 2001. pp. 101–120. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schimel DS. Glob Change Biol. 1995;1:77–91. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Diamond J. Collapse: How Societies Choose or Fail to Succeed. New York: Viking; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fresco NL. PhD dissertation. Fairbanks: Univ of Alaska; 2006. [Google Scholar]