Abstract

Naturally occurring cell death is a universal feature of developing nervous systems that plays an essential role in determining adult brain function. Yet little is known about the decisions that select a subset of CNS neurons for survival and cause others to die. We report that postnatal day 0 NMDA receptor subunit 1 (NMDAR1) knockout mice display an ≈2-fold increase in cell death in the brainstem trigeminal complex (BSTC), including all four nuclei that receive somatosensory inputs from the face (principalis, oralis, interpolaris, and caudalis). Treatment with the NMDA receptor antagonist dizocilpine maleate (MK-801) for 24 h before birth also caused an increase in cell death that reached statistical significance in two of the four nuclei (oralis and interpolaris). The neonatal sensitivity to NMDA receptor hypofunction in the BSTC, and in its main thalamic target, the ventrobasal nucleus (VB), coincides with the peak of naturally occurring cell death and trigeminothalamic synaptogenesis. At embryonic day 17.5, before the onset of these events, NMDAR1 knockout does not affect cell survival in either the BSTC or the VB. Immunostaining for active caspase-3 and the neuronal marker Hu specifically confirms the presence of dying neurons in the BSTC and the VB of NMDAR1 knockout neonates. Finally, genetic deletion of Bax rescues these structures from the requirement for NMDA receptors to limit naturally occurring cell death. Taken together, the results indicate that NMDA receptors play a survival role for somatosensory relay neurons during synaptogenesis by inhibiting Bax-dependent developmental cell death.

Keywords: brainstem, neuroprotection, sensory systems, trophic, ventrobasal

Neurons in the peripheral nervous system avoid developmental cell death by successfully competing for a limiting supply of neurotrophins from synaptic target tissues (1). The situation in the developing CNS is less clear, where the survival-promoting action of neurotrophins on central neurons is complemented, facilitated, or replaced by other forms of support (2). A strong candidate for this role is the electrical activity that is present in developing neurons and neural circuits (3–5). Most neurons, including those in the somatosensory relay nuclei, express NMDA receptors before or just after exiting the cell cycle, well before synapses are established (6–10). Eliminating NMDA receptor function dramatically increases neuronal cell death during development (11–17), and NMDA receptor hypofunction has been proposed to play a causal role in fetal alcohol syndrome and schizophrenia (18, 19). However, the biological significance and the molecular mechanisms of NMDA receptor-regulated neuronal survival in the intact brain remain largely unknown.

NMDA receptors are best known for their role in synaptic plasticity. In the adult brain many forms of long-term potentiation and long-term depression require NMDA receptor function (20). During development, the refinement and plasticity of nascent synapses have also been shown to be dependent on NMDA receptors (21, 22). A canonical system for investigating synaptic development in vivo is the rodent whisker-to-barrel system, also known as the trigeminal system of whisker representations (23). Pharmacological and transgenic manipulations have demonstrated that NMDA receptors are required for normal development of the whisker representations at all three central levels of the trigeminal pathway: the brainstem trigeminal complex (BSTC), the ventrobasal nucleus (VB), and the primary somatosensory cortex (24–28). Therefore, we set out to understand NMDA receptor-dependent cell survival during development in the context of this highly characterized system.

We previously reported that genetic deletion or pharmacological blockade of NMDA receptors induces up to a 5-fold increase in developmental cell death in the VB of neonatal mice (15). This increase occurs during, but not before, the period of synaptogenesis and naturally occurring cell death. Here we report that genetic deletion of NMDA receptors induces an ≈2-fold increase in cell death in the BSTC during the period of naturally occurring cell death and synaptogenesis. This increase in cell death due to NMDA receptor hypofunction depends on Bax, and we provide evidence that neurons are among the dying cells. The results demonstrate that NMDA receptors regulate neuronal selection during Bax-dependent naturally occurring cell death and that different parts of the developing brain are differentially sensitive to NMDA receptor hypofunction.

Results

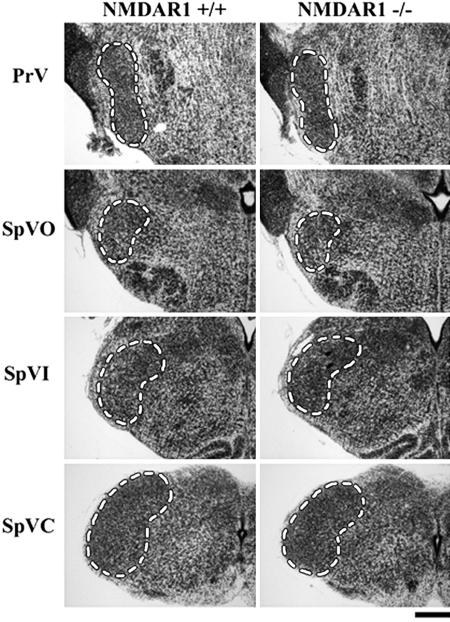

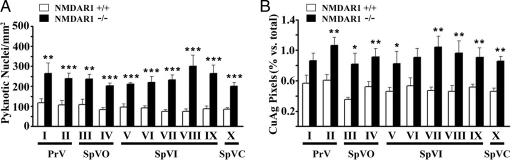

The developing BSTC was analyzed for cell death at 10 anatomically matched rostrocaudal levels (I–X) in the presence and absence of NMDA receptor function. We investigated the impact of eliminating NMDA receptor function at postnatal day 0 (P0), the peak of both naturally occurring cell death within the BSTC and synaptogenesis with its major thalamic target, the VB (29, 30). Representative Nissl-stained coronal sections from the four BSTC nuclei at P0 are shown in Fig. 1: principalis (PrV), oralis (SpVO), interpolaris (SpVI), and caudalis (SpVC). Genetic deletion of NMDA receptor subunit 1 (NMDAR1), an essential subunit for NMDA receptor function, increases pyknotic nuclei and de Olmos cupric silver staining for degenerating cells by ≈2-fold throughout the P0 BSTC (Fig. 2). This increase reaches statistical significance at all 10 levels for counts of pyknotic nuclei (Fig. 2A) and in 8 of 10 levels for cupric silver staining (Fig. 2B). As in the VB, the results were confirmed by active caspase-3 immunohistochemistry, and NMDAR1 knockout does not increase cell death in the BSTC at embryonic day 17.5 (E17.5), before or just at the onset of naturally occurring cell death and trigeminothalamic synaptogenesis (15, 29, 30) (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

The BSTC in developing wild-type (+/+) and NMDAR1 knockout (−/−) mice. Examples of anatomically matched Nissl-stained coronal sections from P0 mice are shown. Levels corresponding to the BSTC nuclei (outlined) are as follows (rostral to caudal): PrV, levels I and II (II is shown); SpVO, levels III and IV (IV is shown); SpVI, levels V–IX, (VII is shown); SpVC, level X. (Scale bar: 300 μm.) PrV, nucleus principalis; SpVO, nucleus oralis; SpVI, nucleus interpolaris; SpVC, nucleus caudalis.

Fig. 2.

Genetic deletion of NMDAR1 increases developmental cell death in the BSTC. Quantitative analyses of cell death were by Nissl staining for pyknotic nuclei (A) and de Olmos cupric silver (CuAg) staining for degenerating cells (B) at 10 anatomically matched levels in the P0 BSTC (I–X). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between NMDAR1 knockout (−/−, filled bars) and corresponding wild-type control (+/+, open bars) (Student's t test: ∗∗∗, P < 0.001; ∗∗, P < 0.01; ∗, P < 0.05). Bars represent means ± SEM.

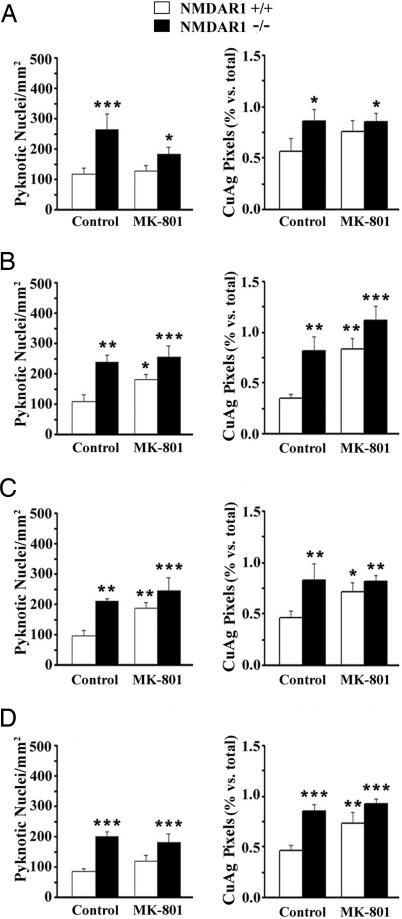

To determine whether pharmacologic blockade of NMDA receptors also increases cell death in the developing BSTC, we treated wild-type (NMDAR1+/+) and NMDAR1 knockout (NMDAR1−/−) mice with the noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 (0.5 mg/kg) for the final 24 h of gestation (E18.5–P0). MK-801 increased counts of pyknotic nuclei and cupric silver staining at all levels of the BSTC versus wild-type controls (Fig. 3). For pyknotic nuclei, the increase reached statistical significance in two of four BSTC nuclei (SpVO and SpVI). For cupric silver staining, the increase reached statistical significance in three of four nuclei (SpVO, SpVI, and SpVC). MK-801 did not cause a further increase in cell death over NMDAR1 knockout alone, indicating that both manipulations increase cell death by the same mechanism, i.e., by decreasing NMDA receptor function.

Fig. 3.

Treatment of wild-type (+/+) mice with the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 for 24 h before birth increases developmental cell death in the BSTC. Results are shown for Nissl-stained (pyknotic nuclei in Left) and cupric silver-stained (CuAg in Right) coronal sections at anatomically matched levels: PrV (A), SpVO (B), SpVI (C), and SpVC (D). Asterisks denote statistically significant differences versus wild-type controls (∗∗∗, P < 0.001; ∗∗, P < 0.01; ∗, P < 0.05). Statistical analyses are by two-way ANOVA. Bars represent means ± SEM.

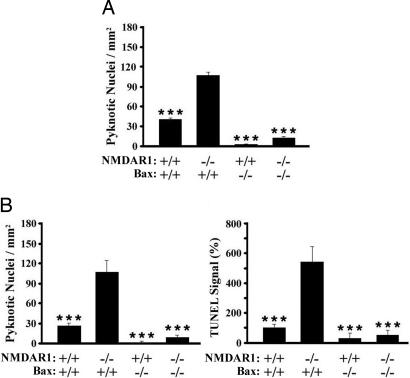

The increase in caspase-3 immunoreactivity in the VB and the BSTC after decreased NMDA receptor function in neonates suggests that eliminating NMDA receptors initiates cell death by apoptosis (15). We therefore used Bax knockout mice (31) to determine whether a classic mitochondrial apoptotic pathway may mediate cell death caused by NMDA receptor hypofunction during development in vivo. P0 NMDAR1/Bax double homozygous knockout mice were generated by breeding Bax/NMDAR1 double heterozygous adults. Coronal sections through the BSTC and VB were Nissl-stained to analyze pyknotic nuclei (Fig. 4), and VB sections were also stained for TUNEL to detect DNA fragmentation (Fig. 4B Right). The results demonstrate that developmental cell death induced by NMDA receptor hypofunction requires Bax.

Fig. 4.

Genetic deletion of Bax rescues the BSTC and the VB from increased developmental cell death because of the absence of NMDAR1. (A) Pyknotic nuclei in the BSTC (PrV, SpVO, SpVI, and SpVC). (B) Pyknotic nuclei (Left) and TUNEL (Right) in the VB (levels III–IV; ref. 15). Genotypes are indicated along the abscissa. Experiments were performed at P0. Statistical analyses are by two-way ANOVA followed by the method of least-square means (∗∗∗, P < 0.001 vs. NMDAR1 knockout). Bars represent means ± SEM.

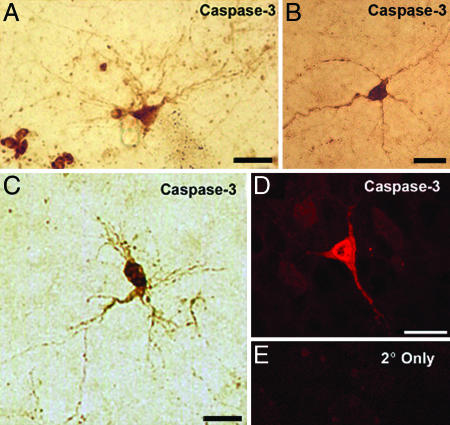

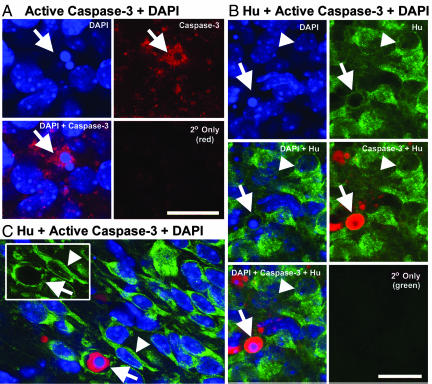

Very little is known regarding the identity of the cells that are vulnerable to NMDA receptor hypofunction in vivo, in part because of the challenge of characterizing cells that have begun to degenerate. In addition to neurons, the developing brain contains progenitors, glia, endothelial cells, and blood cells, and further subclassifications are present within these major categories. Moreover, NMDA receptors are expressed by a number of nonneuronal cell types, including astrocytes and oligodendrocytes (32, 33). Therefore, we used active caspase-3 immunohistochemistry, morphology, and the neuron-specific marker Hu (34, 35) to ask whether dying neurons are present in the BSTC and the VB of P0 NMDAR1 knockout mice. Many active caspase-3-positive cell bodies were ≈10 μm in diameter (Fig. 5), which is in agreement with the diameter of mouse and rat somatosensory relay neurons during the first week of postnatal development (and more than twice the diameter of nonneuronal cells in the VB) (36, 37). Moreover, even though they were dying, in the VB some of these cells displayed morphologies that are typical of barreloid thalamacortical relay neurons (Fig. 5 A and C) (37, 38). To further confirm the presence of dying neurons we performed three-color confocal microscopy analyses for active caspase-3 (Alexa Fluor 568, red), the neuron-specific marker Hu (Alexa Fluor 488, green), and DAPI (blue) to detect pyknotic nuclei (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Active caspase-3-positive cells with neuronal morphology in the neonatal BSTC and VB. Immunohistochemistry for active caspase-3 was performed on sections from the VB (A, C, and D) and the SpVI (B) of P0 NMDAR1−/− mice. Results were visualized by DAB (A–C, light microscopy) or by Alexa Fluor 568 (D and E, fluorescence microscopy). (E) Secondary antibody-only control. (Scale bars: 20 μm.)

Fig. 6.

Dying neurons (arrows) are visualized in the VB (A and B) and the BSTC (C, SpVI) of NMDAR1 knockout neonates by two- and three-color confocal microscopy. Sections were stained with DAPI (blue) for normal and pyknotic nuclei, for active caspase-3 (red), and for the neuron-specific marker Hu (green, B and C only). Series of panels (A and B) represent a single field of view, except secondary (2°) antibody-only controls. Numerous caspase-3-positive cells with pyknotic nuclei (arrows) are the size expected for developing somatosensory relay neurons (≥10 μm in diameter) (A and C). Neuronal identity of dying cells was confirmed by using the neuron-specific marker Hu (B and C). Examples of healthy neurons are indicated by arrowheads in B and C. Inset in C displays the two cells indicated in the main panel, but in the green (Hu)-only channel. (Scale bars: 20 μm.)

Discussion

The balance between cell birth and naturally occurring cell death is critical for normal brain development (39, 40). Upsetting this balance in transgenic mice causes outcomes ranging from lethality to the disruption of learning (41, 42). The major finding reported here is that NMDA receptors regulate cell survival by countering Bax-dependent developmental cell death. This article demonstrates that Bax is required for developmental vulnerability to NMDA receptor hypofunction. Combined with our previous work and studies from other investigators, the results illustrate principles and raise questions regarding NMDA receptor-regulated cell survival during CNS development.

NMDA Receptor Function as a Survival Signal for Developing Neurons in Vivo.

It has been proposed that normal endogenous NMDA receptor function acts as a survival signal for developing neurons. Consistent with this idea, blocking NMDA receptors suppresses Bcl-2 and induces Bax in the forebrain of developing rats (17, 43). The present finding that NMDA receptors, like classic survival factors (e.g., NGF) (44), protect neurons from Bax-dependent developmental cell death provides strong new support for the hypothesis that moderate NMDA receptor activity acts as a survival signal for developing neurons in vivo. Moreover, increased Bax-dependent developmental cell death due to NMDA receptor hypofunction contrasts with Bax-independent cell death that is caused by glutamate receptor excitotoxicity (45).

The survival role played by NMDA receptors is restricted to a period of development that also includes synaptogenesis and rapid growth. However, NMDA receptor-regulated cell survival is not a homogenous event that occurs in all parts of the brain at the same time or to even to the same degree. In the somatosensory system, for example, eliminating NMDA receptors causes a larger increase in cell death in the developing VB (≈3- to 5-fold) (15) than in the BSTC (≈2-fold) (Fig. 2). One possible explanation for such differences in sensitivity to NMDA receptor hypofunction is that vulnerable neurons are those that rely heavily on NMDA receptors for synaptic signaling during synaptogenesis. Consistent with this hypothesis, in neonatal rodents VB neurons rely almost exclusively on NMDA receptors for synaptic signaling; in contrast, synaptic inputs to developing BSTC neurons are mediated by both NMDA and non-NMDA glutamate receptors (24, 30).

A related issue regards the identity of the developing cells that are vulnerable to NMDA receptor hypofunction in the intact brain. Although we have demonstrated that neurons are involved (Figs. 4 and (5; also see ref. 11), it is unknown how individual neurons are selected for cell death while others are spared, and whether other cell types are also affected. To understand the biology and the clinical relevance of NMDA receptors in development it will be critical to understand the mechanism and impact of NMDA receptor-regulated survival on different types of neurons as well as nonneuronal cells.

Mechanisms of NMDA Receptor-Regulated Neuronal Survival in Vitro.

Experiments performed in vitro were the first to demonstrate that developing neurons are vulnerable to NMDA receptor hypofunction and that treatment with low levels of NMDA receptor agonist can enhance neuronal survival (46–49). The present conclusion that NMDA receptors protect against Bax-dependent cell death in vivo is supported by observations that moderate levels of NMDA receptor function increase Bcl-2 and decrease Bax protein levels in cultured cerebellar neurons (50). Moreover, cortical neurons treated with NMDA receptor antagonists release cytochrome c from and translocate Bax to mitochondria (16). It has also been shown in cortical neurons that increased death due to decreased NMDA receptor function requires protein synthesis and is almost completely blocked by insulin-like growth factor I or inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (51, 52).

Hardingham et al. (53) demonstrated in primary cultures of hippocampal neurons that synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors have opposite effects on survival. Low doses of NMDA promote survival via BDNF by increasing both action potentials and synaptic NMDA receptor function. An early phase of protection via synaptic NMDA receptors relies on activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT pathway and is independent of CRE activation; a later, long-lasting phase of protection that persists after synaptic NMDA receptor function ends relies on CRE-dependent gene expression (54). At concentrations of NMDA that are above the toxic threshold, however, synaptic firing is suppressed and extrasynaptic NMDA receptor function dominates, promoting cell death (55).

NMDA Receptor-Dependent Protection from Exogenous Challenge.

Studies using primary cell cultures have shown that NMDA receptor function that is below threshold for toxicity can protect neurons against exogenous insult (56). For example, by suppressing the activation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β, low levels of NMDA receptor agonist protect cortical neurons from apoptosis because of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase blockade (57). Treatment of cortical neurons with cisplatin, a neurotoxic antimitotic, triggers neuroprotective mechanisms by enhancing NMDA receptor activity and thus increasing ERK1/2 signaling (58). Similarly, it has been demonstrated both in vivo and in cell culture that small ischemic events can trigger a NMDA receptor-dependent response that provides protection from subsequent larger ischemic events (59, 60).

Preincubation of cerebellar granule cells, hippocampal neurons, or retinal explants with NMDA protects them from subsequent glutamate excitotoxicity by increasing levels of BDNF available to the cells (61–63). This suggests that BDNF may also facilitate NMDA-dependent attenuation of developmental cell death, a possibility that is supported by the BDNF-mediated protective role of NMDA receptors on developing retinal explants (64, 65). Finally, MK-801 administration during development in vivo induces cell death and decreases both BDNF and active ERK1/2 in the retrosplenial and cingulate cortices, further implicating these molecules in NMDA receptor-dependent protection of developing neurons (17).

Integrated Role of NMDA Receptors in Neuronal Development.

There is considerable evidence that NMDA receptor hypofunction during development can have a negative impact on cognitive function in the adult (66–69). Much remains to be discovered, however, to understand how NMDA receptors contribute to normal and abnormal brain development. NMDA receptors regulate a number of critical events in addition to cell death including division, migration, the elaboration of dendrites, and synaptic refinement (4, 21, 22, 70–74). Because of their temporal overlap it is tempting to speculate that there is a causal relationship between NMDA receptor-regulated cell survival and NMDA receptor-regulated synaptic development. At present, however, it is completely unknown whether this is the case. A better and more clinically productive understanding of NMDA receptor-regulated brain development will elucidate this and other such relationships, as well as the molecular mechanisms that underlie them.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

NMDAR1 knockout mice (24) were originally provided by Y. Li and S. Tonegawa (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA). NMDAR1+/− adults were bred to generate NMDAR1+/+ and NMDAR1−/− littermates, and genotyping was by PCR as previously described (15). For analyses of the BSTC, we used 17 neonatal (P0, equivalent to E19.5) mice: five NMDAR1+/+, four NMDAR1−/−, four NMDAR1+/+ treated with MK-801, and four NMDAR1−/− treated with MK-801. Bax knockout mice were acquired from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) (31). NMDAR1+/−Bax+/− mice were bred to generate NMDAR1/Bax double knockouts and littermate controls. For double knockout experiments, the BSTC and the VB were analyzed in 17 neonatal mice: four NMDAR1+/+Bax+/+, four NMDAR1+/+Bax−/−, four NMDAR1−/−Bax+/+, and five NMDAR1−/−Bax−/−. For the NMDAR1/Bax experiments, PCR analysis was performed by using the following primers: NMDAR1 (mutant, ≈160-bp product), 5′-ATGATGGGAGAGCTGCTCAG and 5′-CAGACTGCCTTGGGAAAAGC; NMDAR1 (wild-type, 240-bp product), 5′-AGCCCTTCAGTACCAGGGCCTGAC and 5′-AGCGGTCCAGCAGGTACAGCATCAC; Bax, 5′-GTTGACCAGAGTGGCGTAGG, 5′-CCGCTTCCATTGCTCAGCGG, and 5′-GAGCTTGATCAGAACCATCATG (wild-type, 304-bp product; mutant, 507-bp product).

Drug Treatment.

Subcutaneous injections of saline or MK-801 (0.5 mg/kg; Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were administered to dams starting 24 h before birth (E18.5) at t = 0, 8, and 16 h as described (10). Plug date is considered E0.5, with a gestation period of 19.5 days.

Tissue Processing.

Neonatal pups were perfused transcardially and fixed, and the brains were processed as described (15) for light microscopy analyses of Nissl (thionine) and cupric silver (CuAg) staining (Figs. 1–3) and active caspase-3 immunostaining (Fig. 5). For NMDAR1/Bax double knockout experiments (Fig. 4), brains were removed at P0, fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated in alcohols followed by xylenes, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned coronally at a thickness of 9 μm. Nissl staining, caspase-3 immunohistochemistry, TUNEL, and cupric silver staining were used to assess cell death. For TUNEL, sections were processed by using the FD NeuroApop Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (FD NeuroTechnologies Consulting and Services, Ellicott City, MD). Three-color fluorescence for DAPI, Hu, and caspase-3 was performed on P0 NMDAR1 knockout brains that were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. The brains were embedded in 2% agar and vibratome sectioned coronally at 100 μm. Free-floating sections were incubated with a rabbit polyclonal anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) and a mouse monoclonal anti-human neuronal protein HuC/HuD (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA), followed by Alexa Fluor 568 (red)-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes) for detecting the anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibody, and Alexa Fluor 488 (green)-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes) for detecting the HuC/HuD antibody. DAPI dihydrochloride (Sigma) was used as a nuclear counterstain. Sections were analyzed on a Bio-Rad 2100 confocal microscope equipped with LaserSharp 2000 software.

Quantification.

Boundaries of the VB and nuclei in the BSTC were determined anatomically on Nissl-stained sections (75). For Nissl-stained sections, pyknotic nuclei were defined by heterochromatin clumping and minimal cytoplasm, and they were counted at the microscope at a magnification of ×40. For CuAg staining, images were photographed under a total magnification of ×40, displayed on the computer screen, and the number of pixels representing CuAg signal was measured as a percentage of the total number of pixels in the nucleus. Results were quantified on one to three sections per BSTC nucleus per animal and on two to six sections per VB per animal. Statistical calculations gave equal weight to data obtained from different sections representing a particular structure or level in a given animal. Quantitative analyses were performed blind to genotype and drug treatment of the animals.

Statistical Analysis.

For comparisons involving multiple comparisons (Bax experiments, experiments comparing NMDAR1+/+, NMDAR1+/+ treated with MK-801, NMDAR1−/−, and NMDAR1−/− treated with MK-801), significance was evaluated by two-way ANOVA (95% confidence level). By using this method, interactions were not detected between NMDAR1 genotype and MK-801 (P ≥ 0.09) (Fig. 3). Interaction was detected, however, between NMDAR1 and Bax (P ≤ 0.01) (Fig. 4). This interaction was corrected for, and significance was evaluated after the test by the method of least-square means. Student's t test was used for comparisons involving only two groups (NMDAR1+/+ and NMDAR1−/−). In addition, two-way ANOVAs revealed no significant impact of level on cell survival (Fig. 2).

Acknowledgments

We thank Suzanne Adams for assistance with generating mice; Dr. Marthe Howard for shaing resources; and Dr. Phyllis Pugh, Janet Lambert, and Nathan Kenyon for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by a Louisiana Board of Regents Research Competitiveness Subprogram Award (to R.C.), Grant P20RR16816 from the Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence Program of the National Center for Research Resources (National Institutes of Health), and Hurricane Katrina Relief Grants from the Society for Developmental Biology and the Society for Neuroscience.

Abbreviations

- NMDAR1

NMDA receptor subunit 1

- En

embryonic day n

- Pn

postnatal day n

- BSTC

brainstem trigeminal complex

- VB

ventrobasal nucleus.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Miller FD, Kaplan DR. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:1045–1053. doi: 10.1007/PL00000919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewin GR, Barde YA. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1996;19:289–317. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.001445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mennerick S, Zorumski CF. Mol Neurobiol. 2000;22:41–54. doi: 10.1385/MN:22:1-3:041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardingham GE, Bading H. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:81–89. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(02)00040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linden R, Martins RA, Silveira MS. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2005;24:457–491. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LoTurco JJ, Blanton MG, Kriegstein AR. J Neurosci. 1991;11:792–799. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-03-00792.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossi DJ, Slater NT. Neuropharmacology. 1993;32:1239–1248. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watanabe M, Inoue Y, Sakimura K, Mishina M. NeuroReport. 1992;3:1138–1140. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199212000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akesson E, Kjaeldgaard A, Samuelsson EB, Seiger A, Sundstrom E. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2000;119:55–63. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maric D, Liu Q-Y, Grant GM, Andreadis JD, Hu Q, Chang YH, Barker JL, Pancrazio JJ, Stenger DA, Ma W. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61:652–662. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000915)61:6<652::AID-JNR9>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikonomidou C, Bosch F, Miksa M, Bittigau P, Vockler J, Dikranian K, Tenkova TI, Stefovska V, Turski L, Olney JW. Science. 1999;283:70–74. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5398.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu C, Hsieh YL, Yang RC, Hsu HK. Neuroendocrinology. 2000;71:301–307. doi: 10.1159/000054550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monti B, Contestabile A. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:3117–3123. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiske BK, Brunjes PC. J Neurobiol. 2001;47:223–232. doi: 10.1002/neu.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams SM, de Rivero Vaccari JC, Corriveau RA. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9441–9450. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3290-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon WJ, Won SJ, Ryu BR, Gwag BJ. J Neurochem. 2003;85:525–533. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen HH, Briem T, Dzietko M, Sifringer M, Voss A, Rzeski W, Zdzisinska B, Thor F, Heumann R, Stepulak A, et al. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;16:440–453. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olney JW, Wozniak DF, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Ikonomidou C. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2001;7:267–275. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang C, McInnis J, Ross-Sanchez M, Shinnick-Gallagher P, Wiley JL, Johnson KM. Neuroscience. 2001;107:535–550. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00384-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malenka RC, Bear MF. Neuron. 2004;44:5–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodman CS, Shatz CJ. Cell. 1993;72(Suppl):77–98. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Constantine-Paton M, Cline HT. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1998;8:139–148. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Killackey HP, Rhoades RW, Bennett-Clarke CA. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:402–407. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93937-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y, Erzurumlu RS, Chen C, Jhaveri S, Tonegawa S. Cell. 1994;76:427–437. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fox K, Schlaggar BL, Glazewski S, O'Leary DDM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5584–5589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitrovic N, Mohajeri H, Schachner M. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:1793–1802. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iwasato T, Erzurumlu RS, Huerta PT, Chen DF, Sasaoka T, Ulupinar E, Tonegawa S. Neuron. 1997;19:1201–1210. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80412-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwasato T, Datwani A, Wolf AM, Nishiyama H, Taguchi Y, Tonegawa S, Knopfel T, Erzurumlu RS, Itohara S. Nature. 2000;406:726–731. doi: 10.1038/35021059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ashwell KW, Waite PM. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1991;63:291–295. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leamey CA, Ho SM. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1998;105:195–207. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(97)00170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knudson CM, Tung KSK, Tourtellotte WG, Brown GA, Korsmeyer SJ. Science. 1995;270:96–99. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5233.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conti F, Minelli A, DeBiasi S, Melone M. Mol Neurobiol. 1997;14:1–18. doi: 10.1007/BF02740618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong R. BioEssays. 2006;28:460–464. doi: 10.1002/bies.20402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marusich MF, Furneaux HM, Henion PD, Weston JA. J Neurobiol. 1994;25:143–155. doi: 10.1002/neu.480250206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okano HJ, Darnell RB. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3024–3037. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-09-03024.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matthews MA, Narayanan CH, Narayanan Y, Onge MF. J Comp Neurol. 1977;173:745–772. doi: 10.1002/cne.901730407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zantua JB, Wasserstrom SP, Arends JJ, Jacquin MF, Woolsey TA. Somatosens Mot Res. 1996;13:307–322. doi: 10.3109/08990229609052585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Varga C, Sik A, Lavallee P, Deschenes M. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6186–6194. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-06186.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oppenheim RW. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1991;14:453–501. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.14.030191.002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buss RR, Oppenheim RW. Anat Sci Int. 2004;79:191–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-073x.2004.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roth KA, D'Sa C. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2001;7:261–266. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rondi-Reig L, Mariani J. Brain Res Bull. 2002;57:85–91. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00639-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hsu H-K, Shao P-L, Tsai K-L, Shih H-C, Lee T-Y, Hsu C. J Mol Endocrinol. 2005;34:433–445. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davies AM. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R374–R376. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00480-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dargusch R, Piasecki D, Tan S, Liu Y, Schubert D. J Neurochem. 2001;76:295–301. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Balazs R, Jorgensen OS, Hack N. Neuroscience. 1988;27:437–451. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90279-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Balazs R, Hack N, Jorgensen OS. Neurosci Lett. 1988;87:80–86. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90149-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brenneman DE, Forsythe ID, Nicol T, Nelson PG. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1990;51:63–68. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(90)90258-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan GM, Ni B, Weller M, Wood KA, Paul SM. Brain Res. 1994;656:43–51. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91364-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu D, Wu X, Strauss KI, Lipsky RH, Qureshi Z, Terhakopian A, Novelli A, Banaudha K, Marini AM. J Neurosci Res. 2005;80:104–113. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takadera T, Matsuda I, Ohyashiki T. J Neurochem. 1999;73:548–556. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takadera T, Sakamoto Y, Ohyashiki T. Brain Res. 2004;1020:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hardingham GE, Fukunaga Y, Bading H. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:405–414. doi: 10.1038/nn835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Papadia S, Stevenson P, Hardingham NR, Bading H, Hardingham GE. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4279–4287. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5019-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Soriano FX, Papadia S, Hofmann F, Hardingham NR, Bading H, Hardingham GE. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4509–4518. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0455-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hetman M, Kharebava G. Curr Top Med Chem. 2006;6:787–799. doi: 10.2174/156802606777057553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Habas A, Kharebava G, Szatmari E, Hetman M. J Neurochem. 2006;96:335–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gozdz A, Habas A, Jaworski J, Zielinska M, Albrecht J, Chlystun M, Jalili A, Hetman M. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43663–43671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301554200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kato H., Liu Y, Araki T, Kogure K. Neurosci Lett. 1992;139:118–121. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90871-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grabb MC, Choi DW. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1657–1662. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-05-01657.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marini AM, Paul SM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6555–6559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marini AM, Rabin SJ, Lipsky RH, Mocchetti I. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29394–29399. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rocha M, Martins RA, Linden R. Brain Res. 1999;827:79–92. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jiang X, Tian F, Mearow K, Okagaki P, Lipsky RH, Marini AM. J Neurochem. 2005;94:713–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martins RA, Silveira MS, Curado MR, Police AI, Linden R. J Neurochem. 2005;95:244–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Deutsch SI, Mastropaolo J, Rosse RB. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1998;21:320–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Anand KJ, Scalzo FM. Biol Neonate. 2000;77:69–82. doi: 10.1159/000014197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ikonomidou C, Bittigau P, Ishimaru MJ, Wozniak DF, Koch C, Genz K, Price MT, Stefovska V, Horster F, Tenkova T, et al. Science. 2000;287:1056–1060. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang C, Kaufmann JA, Sanchez-Ross MG, Johnson KM. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:287–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen C, Tonegawa S. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1997;20:157–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cline HT. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:118–126. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00182-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Erzurumlu RS, Kind PC. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:589–595. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01958-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yacubova E, Komuro H. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2003;37:213–234. doi: 10.1385/cbb:37:3:213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nacher J, McEwen BS. Hippocampus. 2006;16:267–270. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotactic Coordinates. 4th Ed. San Diego: Academic; 1998. [Google Scholar]