Abstract

Matrix metalloproteases regulate both physiological and pathological events by processing matrix proteins and growth factors. ADAMTS1 in particular is required for normal ovulation and renal function and has been shown to modulate angiogenesis. Here we report that TSP1 and 2 are substrates of ADAMTS1. Using a combination of mass spectrometry and Edman degradation, we mapped the cleavage sites and characterized the biological relevance of these processing events. ADAMTS1 cleavage mediates the release of polypeptides from the trimeric structure of both TSP1 and 2 generating a pool of antiangiogenic fragments from matrix-bound thrombospondin. Using neo-epitope antibodies we confirmed that processing occurs during wound healing of wild-type mice. However, TSP1 proteolysis is decreased or absent in ADAMTS1 null mice; this is associated with delayed wound closure and increased angiogenic response. Finally, TSP1−/− endothelial cells revealed that the antiangiogenic response mediated by ADAMTS1 is greatly dependent on TSP1. These findings have unraveled a mechanistic explanation for the angiostatic functions attributed to ADAMTS1 and demonstrated in vivo processing of TSP1 under situations of tissue repair.

Keywords: angiogenesis, extracellular matrix, matrix metalloproteases, thrombospondin, wound healing

Introduction

Remodeling of the extracellular matrix is an essential requirement for development, repair and homeostasis of normal tissues (Mott and Werb, 2004). Among the molecules responsible for these events are the matrix metalloproteases. These constitute a major group of extracellular and membrane-bound enzymes involved in the selective digestion and processing of proteins, glycoproteins and growth factors located outside the cell (Mott and Werb, 2004; Lee et al, 2005b). Like many other metalloproteases, ADAMTS1 (A Disintegrin And Metalloprotease with ThrombosSpondin) is a secreted, zinc-binding enzyme broadly expressed during development and in several adult tissues (Thai and Iruela-Arispe, 2002; Lee et al, 2005a). However, unlike many other metalloproteases in which loss-of-function showed a minimal phenotype, genetic inactivation of ADAMTS1 results in either embryonic lethality (in about 40% of null mice) or postnatal lethality due to severe kidney dysfunction (Shindo et al, 2000; Mittaz et al, 2004; Lee et al, 2005a). Mice homozygous for the null allele also display multiple defects in the female reproductive tract including poor fertility and anomalies in uterine structure (Russell et al, 2003). In addition, mice suffer from stunted growth and showed adrenal abnormalities (Shindo et al, 2000). Together, these outcomes stress the relevance of ADAMTS1 during development and homeostasis of several adult organs.

Mechanistic understanding of the phenotype associated with ADAMTS1 inactivation requires a concrete knowledge of its catalytic profile, that is, biological substrates, and information of other noncatalytic functions. Towards this goal, several groups have identified: (1) substrates for ADAMTS1 that, to date, include aggrecan, versican and nidogen (Kuno et al, 2000; Sandy et al, 2001; Rodriguez-Manzaneque et al, 2002; Canals et al, 2006); (2) catalytic modifiers, such as fibulin1 (Lee et al, 2005a) and (3) noncatalytic function such as sequestration of VEGF to reduce signaling via this ligand (Luque et al, 2003).

Some of the substrates identified for ADAMTS1 have been linked to the pathologies displayed by the null mouse such as inability to ovulate due to lack of versican cleavage (Russell et al, 2003). Nonetheless, many of the other defects remain to be explained at a molecular level. To further expand our knowledge of substrates for ADAMTS1, we tested several potential candidates. Our strategy focused on extracellular proteins located in basement membranes, as the expression profile of ADAMTS1 includes several epithelia (kidney, lung and epidermis) and blood vessels (Thai and Iruela-Arispe, 2002; Gunther et al, 2005). Furthermore, basement membrane components have been shown to regulate differentiation and migration of endothelial cells during angiogenesis (Kalluri, 2003). Here we showed that TSP1, a constitutive component of epithelial and endothelial basement membrane, is cleaved by ADAMTS1.

Thrombospondins (TSPs) are a family of secreted glycoproteins broadly and highly expressed during development (Iruela-Arispe et al, 1993). In addition, TSPs have been associated with the regulation of several processes in the adult including angiogenesis, wound healing and collagen fibril assembly (Bornstein et al, 2000; Lawler, 2000, 2002; Lawler and Detmar, 2004). From all five members of the TSP family, only TSP1 and 2 inhibit angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo (Lawler and Detmar, 2004). The antiangiogenic domain has been mapped to the type I (or TSR) repeats present in TSP1 and 2, a motif that is absent in TSPs 3, 4 and 5. Here we show that processing of TSP1 by ADAMTS1 releases bioactive polypeptides with antiangiogenic properties, demonstrate that this cleavage event occurs in vivo, and explore the biological consequences of TSP processing in mice that lack ADAMTS1.

Results

TSP1 is cleaved by ADAMTS1

To test the hypothesis that basement membrane proteins are substrates for ADAMTS1, we exposed both TSP1 and laminin to the enzyme in vitro. Analysis of the digestion by electrophoretic mobility under reducing conditions revealed two smaller polypeptides of 110 and 36 kDa in the TSP1 sample visible by Coomassie. In contrast, under the same conditions ADAMTS1 did not cleave laminin (Figure 1A). An assortment of several matrix proteins, including TSP1, has been previously used in ADAMTS1 enzymatic assays and indicated no cleavage (Rodriguez-Manzaneque et al, 2002). However, those analyses were performed using antibodies and nonreduced conditions and this prevented visualization of released fragments.

Figure 1.

TSP1 and 2 are cleaved by ADAMTS1 at unique sites. (A) Coomassie stained gel of full-length TSP1 and Laminin incubated with ADAMTS1. Arrows indicate the 110 and 36 kDa cleavage fragments. (B) Western immunoblot of TSP1 incubated with ADAMTS1 or thrombin. (C) Western immunoblots of TSP1 and 2 incubated with ADAMTS1. (D) Western immunoblot of TSP1 incubated with ADAMTS1, catalytically inactive ADAMTS1 (E385A) or a truncated ADAMTS1 form that only harbors type I repeats (TSRs) for indicated times. (E) Western immunoblot of TSP2 incubated with ADAMTS1, catalytically inactive ADAMTS1 (E385A) or a truncated ADAMTS1 form that only harbors type I repeats (TSRs) for indicated times. Open arrow, fragment already present in preparation that is not susceptible to ADAMTS1 cleavage.

Purification of TSP1 entails thrombin-induced platelet degranulation and because thrombin is a recognized protease for TSP1 (Lawler et al, 1986a, 1986b), we asked if TSP1 fragments could potentially be the result of contaminating thrombin activity. To test this, TSP1 was incubated with 2 or 5 U of thrombin. Analysis by Western immunoblot with a polyclonal anti-TSP1 antibody (GPC) confirmed that the fragment derived from ADAMTS1 cleavage, 36 kDa, was distinct from the fragment released by thrombin, 25 kDa (Figure 1B).

TSP2 is also a substrate for ADAMTS1

TSP1 and 2 share identical structural features and are 32–82% conserved in amino-acid sequence depending on the specific domain (Bornstein, 1992). Thus, we were interested in determining whether TSP2 might also be a substrate for ADAMTS1. In vitro digestion assays revealed that ADAMTS1 released two fragments of 42 and 30 kDa (Figure 1C).

To ensure that cleavage of both TSP1 and 2 by ADAMTS1 did not result from possible contaminating proteases, a catalytically inactive ADAMTS1 (E385A) and the ADAMTS1 C-terminal fragment (TSRs) lacking the catalytic domain were incubated with TSP1 and 2 in parallel. The inactive ADAMTS1 (E385A) and the C-terminal fragment were purified from the same cell expression system following a similar protocol. Consequently, any contaminating protease would also be present in these preparations. Both TSP1 and 2 were cleaved only by active ADAMTS1 (Figure 1D and E). These experiments confirmed that TSP1 and 2 cleavage resulted specifically from the catalytic activity of ADAMTS1. In addition, at an enzyme:substrate (E:S) ratio of 1:2.5, TSP1 was cleaved by ADAMTS1 in 5 min (Figure 1D). At the same ratio, TSP2 was cleaved by ADAMTS1 releasing a 42 kDa fragment in 15 min and into a second 30 kDa fragment in 1 h (Figure 1E). In certain TSP1 protein preparations, a 60 kDa fragment was already present in the starting material, but were not susceptible to ADAMTS1 (Figure 1A and D, open arrow).

To assess the cleavage efficiency of TSP1 and 2 by ADAMTS1, the proteins were incubated with varying ratios of ADAMTS1 for 1 h at 37°C. E:S ranged from 1:1 to 1:40. Within 1 h, half of the starting full-length TSP1 was processed at an E:S of 1:40 (Figure 2A). Cleavage of TSP2 by ADAMTS1 was not as effective; an E:S of 1:5 was required to cleave 30% of the starting full-length TSP2 (Figure 2B). However, proteolysis of both TSP1 and 2 was dose-dependent as more ADAMTS1 yielded increasingly more cleavage products (Figure 2A and B, arrows).

Figure 2.

ADAMTS1 cleavage of TSP1 and 2 occurs in a dosage-dependent manner. (A, B) Western immunoblots of TSP1 and 2 incubated with ADAMTS1 for 1 h at 37°C at E:S ranging from 1:1 to 1:40. (C, D) Western immunoblots of TSP1 and 2 incubated with ADAMTS1 in pH ranging from 5.0 to 8.5. Arrowheads, intact TSP1 and 2; arrows, TSP1 and 2 cleavage fragments. Tables under each blot indicate densitometric quantification of the bands. Numbers are in percentile of relative intensity in relation to the darkest band in the blot.

To determine if proteolysis occurs at physiological pH, TSP1 and 2 were incubated with ADAMTS1 at a pH range of 5.0 to 8.5 at an E:S of 1:20. Maximum efficiency for cleavage of TSP1 occurred at pH 6.5 to 8.5 and for TSP2 at pH 7.0 to 8.5.

TSP2 was cleaved by ADAMTS1 at two distinct sites to generate a 42 and a 30 kDa polypeptide. Kinetics experiments revealed a sequential release of these fragments (Figure 1E). In addition, increasing molar ratio of ADAMTS1 favors the generation of the 30 kDa fragment (Figure 2B). These data suggest that the initial cleavage releases the 42 kDa fragment and a second event releases the 30 kDa fragment.

Cleavage of TSP1 and 2 by ADAMTS1 is not shared by ADAMTS4

ADAMTS1 and ADAMTS4 display high sequence homology and share the substrates, aggrecan and versican (reviewed by Apte, 2004). Thus, we sought to determine whether TSP1 and 2 are also cleaved by ADAMTS4. Both TSP1 and 2 were not cleaved by ADAMTS4 compared to ADAMTS1 at the same molar concentration (Figure 3A and B). To verify that ADAMTS4 was active, aggrecan was digested with both ADAMTS1 and ADAMTS4. As expected, both were able to cleave aggrecan, although ADAMTS4 was a more effective enzyme for aggrecan than ADAMTS1 (Figure 3C). Aggrecan is cleaved by both ADAMTS1 and ADAMTS4 to 200 kDa as well as 65 kDa (Sandy et al, 2000; Rodriguez-Manzaneque et al, 2002). ADAMTS4 is more efficient at cleaving aggrecan hence majority of the product was 65 kDa in mass. In contrast, ADAMTS1 is less efficient at cleaving aggrecan yielding mainly 200 kDa fragments.

Figure 3.

TSP1 and 2 are not substrates of ADAMTS4. (A, B), Western immunoblots of TSP1 and 2 incubated with ADAMTS1, ADAMTS4 and vehicle. (C) Western immunoblots of aggrecan incubated with ADAMTS1, ADAMTS4 or vehicle. (D, E) Western immunoblots of TSP1 and 2 incubated with varying amounts of 87 kDa ADAMTS1 and 65 kDa ADAMTS1, as indicated. Arrowheads, intact TSP1 and 2; arrows, TSP1 and 2 cleavage fragments.

Heparin binding domains of TSP1, TSP2 and ADAMTS1 are necessary for efficient cleavage

The N-terminal domain of TSP1 and 2, as well as TSR repeats of ADAMTS1 have been shown to interact with heparin (Murphy-Ullrich et al, 1993; Kuno and Matsushima, 1998; Rodriguez-Manzaneque et al, 2000). We considered that these domains might facilitate docking and subsequent cleavage. To test this possibility, TSP1 was incubated with the full-length active ADAMTS1 (87 kDa) and with truncated active ADAMTS1 (65 kDa), which lacks part of the spacer region and the last two TSRs, and displays lower affinity for heparin (Rodriguez-Manzaneque et al, 2000). The truncated form of ADAMTS1 required a higher E:S (2:1) to achieve near complete processing of intact TSP1 within 2 h in comparison to 87 kDa ADAMTS1, which completely processed intact TSP1 at an E:S of 1:10 (Figure 3D). TSP2 was also incubated with 65 and 87 kDa forms of ADAMTS1. The 65 kDa form of ADAMTS1 was rather inefficient at processing intact TSP2, as an E:S of 1:1 was required to release the 42 kDa TSP2 N-terminal fragment visible by Western blot (Figure 3E). The 87 kDa ADAMTS1 was more efficient at cleaving intact TSP2 (Figure 3E).

The reciprocal experiment was carried out by incubating truncated mutants of TSP1 and 2 lacking the heparin binding domain (delN-1 and delN-2) with ADAMTS1. In comparison to intact TSP1, which was completely processed, delN-1 was not cleaved as efficiently, as only half was processed (Figure 4B (i)). In turn, delN-2 was not cleaved by ADAMTS1 (Figure 4B (ii)). To discard concerns related to structural changes of deletion mutants, we tested another deletion mutant, NoC, which has the N-module necessary for heparin binding. Both NoC-1 and NoC-2 were cleaved by ADAMTS1 (Figure 4C (i and ii)).

Figure 4.

Heparin binding domains are important for cleavage. (A) schematic diagram of full-length TSP1 and 2 and deletion mutants. (B (i, ii), Western immunoblots and Coomassie staining of full-length TSP1 and delN-1 or TSP2 and delN-2 digested with ADAMTS1. (C (i, ii)), Western immunoblots and Coomassie staining of full-length TSP1 and truncated mutant NoC-1truncated or TSP2 and NoC-2 digested with ADAMTS1. Open arrows, ADAMTS1 protein. (D (i, ii)) TSP1 and 2 digested with ADAMTS1 in presence of increasing amounts of heparin. Arrowhead, full-length protein; arrows, cleaved fragments.

To test whether heparin affects TSP1 and 2 processing, we incubated both TSP proteins with ADAMTS1 at an E:S of 1:40 in the presence of increasing amounts of heparin. TSP1 cleavage was not affected by heparin (Figure 4D (i)), similarly, the more carboxy terminal cleavage site in TSP2, which yield the 42 kDa fragment was not altered (Figure 4D (ii)). However, generation of the 30 kDa fragment was suppressed by heparin (Figure 4D (ii)). This would indicate that rather than altering enzymatic activity, heparin binds to one of the sites in TSP2 and hampers the ability of ADAMTS1 to dock and cleave within this site. Nonetheless, based on the previous findings, the heparin-binding region in TSP1 and 2 appears to function independent from heparin to facilitate processing by ADAMTS1.

Identification of cleavage sites

Analysis of with MALDI-TOF MS determined that the 36 kDa fragment corresponds to the N-terminus of TSP1 and the 110 kDa fragment corresponds to the C-terminus. Analysis repeated with LC MS yield the same result (data not shown). Because the 110 kDa fragment exposes the cleavage site at the N-terminal region, we transferred it onto PVDF membrane and performed N-terminal Edman degradation sequencing. One of the resulting peptides contained the LRRPPL sequence indicating that cleavage occurred between residues: glutamic acid 311 and leucine 312 (Figures 5A and 6A). This site is consistent with the classification of glutamyl endopeptidase attributed to ADAMTS1 based on cleavage of other substrates such as aggrecan and versican (Rodriguez-Manzaneque et al, 2002; Westling et al, 2002). Similarly, higher-molecular weight TSP2 doublets released by ADAMTS1 cleavage were also analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS and determined to correspond to the C-terminal fragment lacking the N-terminal domain (data not shown). Both fragments were transferred to PVDF, Edman sequencing resolved only the lower doublet fragment and revealed the sequence LIGGPP (Figure 5B). This indicates that one of the cleavage sites in TSP2 lies between glutamic acid 306 and leucine 307 (Figure 6A).

Figure 5.

TSP1 and 2 cleavage sites and schematic representation of resulting fragments. (A) TSP1 is cleaved at one site C1 by ADAMTS1 adjacent to amino-acid sequence LRRPPL (determined by Edman degradation sequencing). (B) TSP2 is cleaved at two sites C1 and C2. Site C1 is adjacent to amino acids LIGGPP. Proteins were visualized with Coomassie. Asterisk in (A) represents ADAMTS1.

Figure 6.

N-terminal fragments remain trimerized releasing the monomeric C-terminal fragments. (A) Sequence alignment of TSP1 and 2 including region in proximity of cleavage sites. Boxed region represents pro-collagen domain. Underlined sequence corresponds to the coiled-coil region. Asterisks denote cysteines involved in interchain disulfide bonds. Inset, schematic representation of N-terminal and C-terminal fragments in reducing (R) and nonreducing (NR) conditions. (B, C) Western immunoblots of TSP1 and 2 incubated with ADAMTS1 or vehicle under nonreducing and reducing conditions.

The second cleavage site in TSP2 remains to be determined; however, the monoclonal antibody used to detect TSP2 (3C5.3) recognizes the N-module, indicating that this cleavage is likely occur towards the N-terminal region.

Proteolytic activity of ADAMTS1 releases monomeric C-terminal peptides from TSP1 and 2

Native TSP1 and 2 exist as homotrimers linked by intermolecular disulfide bonds and the coiled-coil oligomerization domain (Engel, 2004). Additional intramolecular disulfide bonds exist within the linker region between the coiled-coil domain and the procollagen homology domain (Misenheimer et al, 2000). Based on the mapped cleavage site, ADAMTS1 proteolysis could have two possible outcomes: (1) release the C-terminus fragment from the N-terminus fragment; or (2) cleavage could target the disulfide bond region resulting in a nicked protein where the N-terminus remains attached to the C-terminus by disulfide bonds. To distinguish between these two possibilities, digested proteins were separated under reducing and nonreducing conditions (Figure 6B and C). The 36 kDa N-terminus fragment of TSP1 (reducing condition) was detected as a 108 kDa fragment (nonreducing) (Figure 6B), indicating that the N-terminus remained trimerized after ADAMTS1 cleavage. Since the N-terminus is the only known region required to mediate trimer formation, the 110 kDa C-terminus fragment is released in a monomeric form. Analysis of the TSP2 digestion products revealed that ADAMTS1 cleavage of this molecule also releases the C-terminus fragment as a monomer leaving the N-terminus in a trimeric form. Under nonreducing conditions, the 42 kDa N-terminus fragment was shifted to a 145-kDa band (Figure 6C). Trimerization of the 42 kDa would yield a complex of approximately 126 kDa in size. The discrepancy between the 142 kDa band and the expected 126 kDa band is likely due to glycosylation. In addition, the 30 kDa N-terminus fragment (reducing condition) shifted to a 90-kDa band (nonreducing condition) corresponding to a trimerized 30-kDa fragment (Figure 6C).

ADAMTS1 cleaves murine TSP1

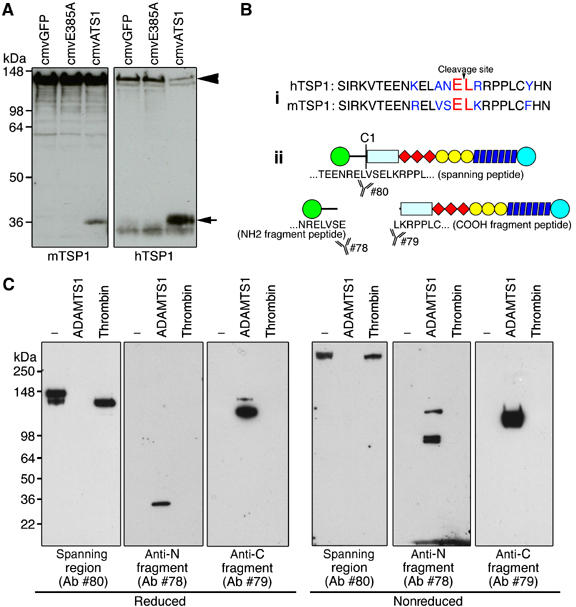

Since murine TSP1 shares high sequence identity to the human orthologue, we assessed whether mTSP1 is also cleaved by ADAMTS1 (Figure 7B). Adenoviral constructs expressing active ADAMTS1, inactive ADAMTS1 or GFP were used to infect 293T cells. Conditioned medium (CM) was collected 24 h postinfection and was subsequently incubated with either purified hTSP1 or mTSP1 from mouse LE II cells at 37°C for 2 h. Under these conditions, mTSP1 was also cleaved by ADAMTS1 releasing a 36 kDa fragment indicating that the cleavage site was likely to be in the same region in both species (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

Characterization of TSP1 neo-epitope antibodies. (A) Western immunoblot of murine and human TSP1 incubated with CM from adenovirus infected cells expressing GFP (cmvGFP), inactive ADAMTS1 (cmvE385A) or full-length active ADAMTS1 (cmvATS1). (B (i)) Sequence alignment of human and murine TSP1 residues flanking cleavage site. (ii) Schematic diagram of TSP1 and fragments recognized by neo-epitope antibodies (78 and 79) and antibody to spanning region (80). (C) Western immunoblot of intact TSP1 and TSP1 fragments resulting from processing with either thrombin or ADAMTS1 under reducing and nonreducing conditions. Arrowhead, full-length TSP1; arrow, TSP1 fragment.

Characterization of neo-epitope antibodies

To further explore the significance of the processing events, we developed neo-epitope antibodies against the cleaved sites and the spanning region using flanking peptides, NRELVSE (#78) and LKRPPLC (#79), and the spanning TEENRELVSELKRPPL peptide (#80). All three antibodies were affinity-purified with their corresponding immunizing peptides and cross-absorbed to eliminate unwanted reactivities. We then tested their specificity against TSP1 cleaved by either thrombin or ADAMTS1. Antibody #78 specifically recognized the 36 kDa TSP1 fragment released by ADAMTS1 cleavage. Similarly, antibody #79 specifically recognized the 110 kDa TSP1 fragment. Antibody #80 recognized intact TSP1 as well as thrombin-cleaved TSP1 as the polypeptide retained the spanning region. All antibodies worked in reduced and nonreduced conditions (Figure 7C).

TSP1 is cleaved by ADAMTS1 during wound healing

It has been previously shown that ADAMTS1 is upregulated in inflammatory situations, a feature also shared by TSP1 (Agah et al, 2002). Thus, we investigated whether TSP1 fragments could be detected in excisional skin wound healing assays at 2-day postinjury. We made full-thickness wounds on the dorsal skin of ADAMTS1 null mice and wild-type siblings.

Intact TSP1 expression was found at the leading wound edge epithelium, fibrin clot and hair follicles in the ADAMTS1 null animals (Figure 8A (d), arrow denotes the leading edge). In comparison, less intense staining of intact TSP1 was found in the leading wound edge of the wild-type siblings (Figure 8A (a)). However, comparable levels of TSP1 protein were localized to the fibrin clot and hair follicles. In contrast, both N- and C-terminal fragments of TSP1 were present on the leading edge in the wound epithelium and hair follicles in wild-type animals (Figure 8A (b and c)). ADAMTS1 null animals displayed less intense staining of both N- and C-terminal TSP1 fragments (Figure 8A (e and f)).

Figure 8.

TSP1 cleavage by ADAMTS1 occurs during excisional wound healing. (A) (a–f) Immunohistochemical staining of intact TSP1 and TSP1 fragments in 2-day excisional wound serial sections using the spanning region antibody (#80) or neo-epitope antibodies (#78 and #79). (Arrow in a–f, invading front of epidermal cells; C: fibrin clot; E: epidermis; F: hair follicles) (A). (g–l), Immunohistochemical staining of intact TSP1 and fragments within fibrin clot. Arrows in (g and j), intact TSP1; arrows in (h), N-terminal TSP1 fragment. (B) Western immunoblot of TSP1 (intact and fragments) immunoprecipitated with anti-TSP1 antibodies (#78, 79 or 80) and anti-occludin (occ). Western immunoblot was performed using either #78, 79 or 80 (arrowhead: C-terminal TSP1 fragment; arrow: N- terminal TSP1 fragment; asterisk: intact TSP1).

ADAMTS1 has been shown to be expressed by CD11b positive cells within the clot by 1-day postinjury (Krampert et al, 2005). We analyzed the localization of TSP1 fragments within the clot of 2-day wounds. As expected, intact TSP1 was found in both wild-type and ADAMTS1 null clots (Figure 8A (g and j), arrows). However, the N-terminal TSP1 fragment was only found in the clot of wild-type animals (Figure 8A (h), arrows). The C-terminal fragment was not visible in either wild type or ADAMTS1 null animals. A finding that suggests that this fragment is likely soluble and short lived (Figure 8A (i and l)).

Immunoprecipitation of wound lysates using the antiamino fragment antibody (#78) pulled down a 40 kDa species in wild-type sample, this fragment was not detected on the ADAMTS1 null sample (Figure 8B, arrow). Similarly, immunoprecipitation with the anticarboxy fragment antibody (#79) pulled down a 110-kDa fragment in the wild-type sample and to a lower degree in the ADAMTS1 null sample (Figure 8B, arrowhead). Immunoprecipitation with the antispanning peptide antibody (#80) was able to precipitate a 145 kDa fragment that corresponds to the intact TSP1 (Figure 8B, asterisk).

At 5-day postinjury, wounds were closed in the wild-type animals and the new epithelial layer covering the wound was thicker than the surrounding epithelia (Figure 9A (a)). In contrast, ADAMTS1 null wounds remained open with poor epithelial migration (Figure 9A (b), arrows). Evaluation of capillary density revealed more vessels in the dermis of ADAMTS1 null mice than in control littermates (Figure 9C and D).

Figure 9.

ADAMTS1 null animals exhibits delayed wound healing and increased angiogenesis. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin stained 5-day wound cross-sections of wild-type and ADAMTS1 null animals. (B) Excisional wound opening area quantified over 5 days in wild-type and adamts1 null animals. Difference in open wound area between wild-type and adamts1 null from day 1 onward has a P-value <0.005. (C) Hematoxylin and eosin (a, d) anti-PECAM stained (b, c, e, f) blood vessels within wound cross-sections. (c) and (f) are magnified images of boxed area in (b) and (e), respectively. (D) Quantification of blood vessels in wounds. Bars indicate standard error. Difference in mean vessel count between wild-type and adamts1 null has a P-value <0.005.

Since ADAMTS1 null wounds exhibited greater vessel density, we explored the possibility that ADAMTS1 might release soluble TSP1 fragments from matrix-bound TSP. Cultures of human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVEC) were exposed to ADAMTS1 or vehicle. ADAMTS1 was able to process intact TSP1 to 110 and 36 kDa fragments, which were detected in the CM. Because in vivo TSP1 is frequently found incorporated in the matrix, we performed a second experiment, using matrix preparations in the absence of cells. Exposure of cell-free extracellular matrices to ADAMTS1 resulted in the processing of TSP1 and release of the 110 kDa C-terminal fragment from matrix-bound TSP1 (Figure 10A, SUP). The N-terminal fragment (Figure 10A, second panel, solid and open arrow) was found both in the supernatant, as well as bound to the matrix in the form of 36 and 25 kDa fragments (this second one, a result of further processing by thrombin).

Figure 10.

TSP1 fragments are released by endothelial cells and suppress proliferation. (A) Western immunoblots of TSP1 (intact and fragments) secreted from cells (CM), in the cell layer (CL), released from the matrix (SUP) or matrix bound (matrix) incubated with vehicle or ADAMTS1 at the indicated amounts. Arrowhead, intact TSP1; asterisk, C-term fragment; arrow, N-term fragment. (B) Elution chromatogram of TSP1 fragments. Elution of proteins was monitored by absorbance (a.u. on left) and conductivity is shown on the right. Fractions containing eluted proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE and visualized by Coomassie staining and Western immunoblotting with anti-TSP1 antibodies. FL, full-length TSP1 protein. (C) [3H]thymidine incorporation in bovine aortic endothelial cells stimulated with GF (FGF-2 and VEGF) and treated with vehicle, full-length TSP1, or purified TSP1 cleavage products (36 and 110 kDa). (D) Phase micrograph of cultured primary mouse lung endothelial cells isolated from wild-type and tsp1 null animals at passage 3. (E) Representative RT–PCR from cDNA of isolated lung endothelial cells from wild-type (lanes 1 and 4) and tsp1 null animals (lanes 2 and 3). (F) [3H]thymidine incorporation in wild-type and tsp1 null mouse lung endothelial cells stimulated with FGF-2 and treated with vehicle or ADAMTS1. [3H]thymidine incorporation shown as an average percent of control.

TSP1 fragments inhibit endothelial cell proliferation

We next examined the effect of these TSP1 fragments on cell proliferation. For these experiments, we first devised a purification procedure to isolate each polypeptide from intact TSP1 (Figure 10B). Both fragments were able to suppress growth factor (FGF-2 and VEGF) induced proliferation (Figure 10C). It should be stressed that in this experimental setting, both fragments were delivered in a soluble form. In tissues, however, only the 110-kDa fragment is likely to be presented in a soluble form and provide antiproliferative signals (see Discussion).

To further explore the relationship between ADAMTS1 and TSP1 in angiogenesis, we isolated endothelial cells from TSP1 null and wild-type mice and evaluated their proliferation in response to ADAMTS1 (Figure 10F). As previously shown, exposure of endothelial cells to ADAMTS1 resulted in inhibition of FGF-2-driven endothelial cell proliferation to approximately 36%. In contrast, the absence of TSP1 significantly attenuates the inhibitory effect mediated by ADAMTS1 (Figure 10F).

Discussion

Proteolytic processing of matrix proteins and growth factors is a mechanism for the generation of bioactive peptides of significant biological impact. Here, we have identified TSP1 and 2 as novel substrates for ADAMTS1, a metalloprotease previously shown to inhibit angiogenesis when used at pharmacological doses in vivo and in vitro (Vazquez et al, 1999; Luque et al, 2003). Interestingly, we further demonstrate that cleavage generates a pool of TSP1 antiangiogenic polypeptides and that this mechanism is essential for most of the endothelial inhibitory activity of ADAMTS1 in vitro. The TSP1 fragments were also detected in wound-healing assays in vivo. Furthermore, the absence of ADAMTS1 was associated with delayed wound healing and enhanced vascular density; a phenotype that mirrors wound healing in TSP1 null mice (Agah et al, 2002; Lawler and Detmar, 2004). Together, these findings argue that the generation of antiangiogenic peptides from TSP1 is a physiologically important function of ADAMTS1.

TSP1 and 2 have been shown to be relevant endogenous inhibitors of angiogenesis (Streit et al, 1999; Rodriguez-Manzaneque et al, 2001). The effects of TSP1 on endothelial cells have been shown to occur, in some cases by direct receptor signaling (Dawson et al, 1997; Jimenez et al, 2000), and in other cases through the ability of TSP1 to interact with other extracellular proteins (Taraboletti et al, 1997; Iruela-Arispe et al, 1999). In fact, by nature of its interaction with proteoglycans, extracellular matrix molecules, proteases and growth factors, TSP1 directs the assembly of multiprotein complexes that modulate cellular function. Understanding the biological significance of TSP-ECM interactions has become a challenge for investigators in this field as the protein has the potential to impact cell function in a context-dependent manner. The generation of TSP1 null mice has demonstrated that this protein is required for the regulation of epithelial growth in the lung, lung homeostasis and wound healing (Lawler et al, 1998; Agah et al, 2002). The absence of TSP1 results in multifocal pneumonia and increased inflammatory events (Lawler et al, 1998). In addition, the animals display hyperplasia of pancreatic islands and show delayed wound healing (Crawford et al, 1998; Agah et al, 2002). Particularly interesting was the observation that TSP1 null animals showed a reduced litter number and increased blood vessel profiles in several organs (Crawford et al, 1998; Lawler et al, 1998).

The antiangiogenic effects of TSP1 have been well documented in several in vivo and in vitro models (Tolsma et al, 1993; Dawson et al, 1997; Taraboletti et al, 1997; Iruela-Arispe et al, 1999). More importantly, genetic manipulations that result in TSP1 overexpression using tissue-specific promoters strongly support the participation of this protein in the regulation of vascular growth and vessel diameter. In particular, two transgenic studies using the K14 promoter to drive TSP1 in the skin (Streit et al, 2000) and, the MMTV-promoter, to target expression to the mammary epithelium (Rodriguez-Manzaneque et al, 2001), support a role for this protein in the regulation of vascular morphogenesis in whole animal settings. TSP1 also modulates the size of vascular channels. These functions are also shared by TSP2, as both molecules shared the antiangiogenic domain located in the TSR repeats (Lawler and Detmar, 2004).

Cleavage of TSP1 and 2 by ADAMTS1 could modulate their functions in one of two ways: it could facilitate remodeling of matrix-associated TSP and/or release bioactive domains that might be unavailable when the protein is integrated in the matrix milieu (Nicosia and Tuszynski, 1994). The last possibility is not entirely surprising, as several studies have demonstrated activation of bioactive antiangiogenic polypeptides generated by proteolysis. Cleavage of collagen IV, XVIII and plasminogen results in the release of angiogenesis inhibitors, a function that is only gained through proteolysis (Cao et al, 1996; Dong et al, 1997; O'Reilly et al, 1999; Ferreras et al, 2000). Alternatively, cleavage of collagen IV by MMP9 unmasks a cryptic site that stimulates migration of endothelial cells and angiogenesis in vivo (Xu et al, 2001; Hangai et al, 2002). Thus, the nature of the cleavage could lead to potentially opposite outcomes. In the case of type IV collagen, both enhancement and suppression of angiogenesis have been demonstrated. Along the same lines, TSP1 was shown to enhance angiogenesis in some settings.

Structural information on TSP1 has been rapidly accumulating. The crystal structure of the N-terminal region has been recently resolved (Tan et al, 2006), as has the procollagen module (O'Leary et al, 2004) and the TSR (antiangiogenic repeats) (Tan et al, 2002). This information combined with the resolution of the last three type 3 repeats and C-terminal domain (Kvansakul et al, 2004) provides a comprehensive atomic information and provides a molecular image for TSP1. Together these data suggest that there is only one flexible, protease-sensitive area that lies between the N-terminal and the oligomerization domain. Indeed, our results show that the cleavage sites within TSP1 and 2 are located within the procollagen domain in proximity of the alpha helical loops and intramolecular disulfide bonds and thus dividing the molecule into two fragments: N-terminal that remains trimeric and a more soluble, monomeric, C-terminal fragment that exposes the TSR/antiangiogenic modules.

Our data have shown that the C-terminal 110 kDa fragment is as potent as intact TSP1 towards inhibiting endothelial cell proliferation and, in vivo, this is likely the fragment that conveys antiangiogenic effects. The state of soluble versus bound TSP1 has important biological relevance when understanding the angiostatic effects of this protein. In fact, several studies have shown that matrix-bound (insoluble) TSP1 stimulates, rather than inhibits angiogenesis (Nicosia and Tuszynski, 1994; Ferrari do Outeiro-Bernstein et al, 2002). Due to its multiple interactions with cells and matrix proteins, once secreted, extracellular TSP1 is incorporated in the extracellular matrix mostly by its N-terminus. The majority of integrin binding sites, as well as, calreticulin binding have been mapped to the beta strands located in the N-terminal region (Krutzsch et al, 1999; Calzada et al, 2003, 2004). Furthermore, the large majority of the protein/proteoglycan-binding motifs have been located within this N-terminal domain. Cleavage of intact matrix-bound TSP1 likely releases a soluble C-terminal monomer and leaving bound trimeric N-terminal fragments. Hence, processing by ADAMTS1 would uncover the antiangiogenic potential of matrix-bound TSP. Together these findings shed light on a long-term controversy in the field as to the pro- and antiangiogenic effects attributed to TSP1 in different experimental settings.

Finally, it is interesting to consider the similarities between the ADAMTS1 and the TSP1 null mice. Both exhibit delay in wound healing, excessive curvature in their spines indicating osteogenic problems and poor fertility in females (Lawler et al, 1998; Shindo et al, 2000; Agah et al, 2002). While these mice do also exhibit nonoverlapping phenotypes, the findings here would indicate that at least in the skin the biology of these two proteins interject and are required for the normal resolution of wound healing and regulated angiogenic progression.

Materials and methods

Reagents

TSP1 was purified as previously described (Rodriguez-Manzaneque et al, 2001). Human TSP2 and truncated TSP1 and 2 fragments (delN-1, delN-2, NoC-1 and NoC-2) were purified as previously described (Annis et al, 2006). Murine TSP1 was collected from culture supernatant secreted by lung endothelial cells (LE II). TSP1 antibody GPC was raised in guinea-pig (GPC) (Rodriguez-Manzaneque et al, 2001). TSP1 antibodies (Ab-9, Ab-4) were purchased from Neomarkers (Fremont, CA): Ab-9=MBC200.1 and binds the heparin binding domain; Ab-4=A6.1 and binds to the first calcium binding loop in the calcium wire (Annis et al, 2006).

TSP2 antibodies 3C5.3 and 1B1.8 were raised in collaboration with the hybridoma core facility at the University of Alabama. The murine monoclonal antibodies 3C5.3 and 1B1.8 are specific for TSP2. 3C5.3 recognizes an epitope in the N-module and 1B1.8 reacts with the third properdin repeat.

Recombinant ADAMTS1 was purified as previously described (Rodriguez-Manzaneque et al, 2000), and dialyzed in 250 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 1 mM CaCl2. Activity of the enzyme was assessed by proteolytic cleavage of aggrecan.

Recombinant ADAMTS1 containing a glutamic acid to alanine mutation (zinc binding mutant, catalytically inactive) and recombinant ADAMTS1 C-terminal fragment (TSRs) were isolated as previously described (Rodriguez-Manzaneque et al, 2002). Recombinant ADAMTS4 was purchased from (Chemicon, CA). Purified aggrecan from rat chondrosarcoma cell line was a gift from Dr John Sandy (Shriners Hosp., FL).

TSP1 fragments (36 and 110 kDa) were purified using heparin HiTrap columns (GE Healtcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Digestion assays

TSP1, TSP2 or laminin were incubated with 87, 65 kDa ADAMTS1 protein or vehicle, at E:S of 1:1 or indicated E:S, in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 10 mM CaCl2, 80 mM NaCl for 2 h at 37°C in a maximum volume of 60 μl. Samples were resolved on 10% or 4–12% gradient (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) SDS–PAGE.

Additional controls for ADAMTS1 cleavage assays included a catalytically inactive ADAMTS1 mutant (E385A), ADAMTS1 C-terminal fragment (TSRs), and ADAMTS4 (Chemicon) for indicated times.

TSP1 and 2 fragments, delN and NoC (1 μg each) were incubated with ADAMTS1 (87 kDa) for 2 h at 37°C and detected with indicated antibodies. TSP1 and 2 (2 μg) were also incubated with ADAMTS1 (50 ng) (E:S of 1:40) in the presence of heparin (Sigma) ranging from 0.5 to 250 ng for 1 h at 37°C.

Densitometric analysis of fragments was performed by scanning with a Personal Densitometer SI (Molecular Dynamics/GE Healthcare) and analyzed with ImageQuant 5.2 (Molecular Dynamics).

Aggrecan assays

Rat aggrecan (10 μg) was incubated with ADAMTS1 and ADAMTS4 (1 μg each) in 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 10 mM CaCl2, 80 mM NaCl for 2 h at 37°C. Samples were deglycosylated with Chondroitinase ABC (Sigma) in 50 mM Tris, 10 mM EDTA pH 8.0 at 37°C for 1 h prior to separation on 10% SDS–PAGE.

Digestion of murine and human TSP1 by cells infected with ADAMTS1 adenovirus

293T cells were infected with adenovirus expressing GFP (control), inactive ADAMTS1 (cmvE385A), or active ADAMTS1 (cmvATS1) at 5 MOI. Infection efficiency was assessed by visualization of GFP and estimated to be 80–85%. CM was collected after 24 h of incubation. Murine TSP1 (CM from LE II cells) and purified hTSP1 (2 μg) were incubated with CM from adenoviral infected 293T cells at 37°C for 4 h.

Mass spectrometry and N-terminal Edman degradation sequencing

TSP1 digested with ADAMTS1 was separated by 10% SDS–PAGE. Bands of interest were excised, digested with trypsin and analyzed with MALDI-TOF-MS (Applied Biosystems Voyager DE-STR mass spectrometer; Foster City, CA), and LC-MS using a nano-HPLC system (Dionex-LC Packings, Sunnyvale, CA) and a QSTAR Pulsar XL (QqTOF; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) mass spectrometer equipped with a nano-electrospray interface (Protana, Denmark). TSP1 and 2 fragments were also separated by 10% tris–glycine gel electrophoresis and transferred to a PVDF membrane (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA). After staining with Ponceau Red, the 110 kDa (TSP1) band and the 100 kDa (TSP2) doublets were excised and Edman N-terminal degradation sequencing was performed by Dr Gary Hathaway (Caltech PPMAL, Pasadena, CA).

Wound assays

Mice (2–4 month old) were anesthesized using an anesthetic vaporizer (Summit Medical, Bend, OR). The skin was shaved and sterilized. Two full-thickness excisional wounds were made on either side of the dorsal midline using 5 mm dermal punches (Krampert et al, 2005).

Wounds were photographed with a Sony DSC-W7 digital camera 13 cm away from the animals daily for 5 consecutive days. Open wound area was measured with ImagePro 5.0 (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD.). Statistical analysis was performed using the paired Student's t-test.

Wound sections were immunostained with anti-PECAM (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Images were captured from five random areas of 0.5 mm2 per wound section at 10 × and vessels counted manually. Statistical analysis was performed using the paired Student's t-test.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded skin wounds serially sectioned from the middle (5 μm thickness) were incubated with rabbit anti-TSP1 neo-epitope antibodies (#78, 79 or 80) at (20, 10 and 10 μg/ml, respectively) and subsequently incubated with anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to FITC (Sigma). Fluorescence IHC was analyzed using an MRC 1024ES confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany).

Tissue lysate preparation and immunoprecipitation

Wounds were ground up in liquid nitrogen and incubated with RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM PMSF, 20 μg/ml leupeptin, 20 μg/ml aprotinin) for 3 h at 4°C. The lysate was precleared using Protein-G agarose beads (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and 4 mg of each lysate was incubated with each anti-TSP1 neo-epitope antibodies (#78, 15 μg, #79, 10 μg and #80, 10 μg) and subsequently with protein G agarose. Bound proteins were released from beads with Laemli buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol and resolved by 4–12% gradient SDS–PAGE (Invitrogen).

Cleavage of TSP1 in cultured HUVEC cells by ADAMTS1

HUVEC (VEC, Rensselaer, NY) were then treated with ADAMTS1 or vehicle for 4 h at 37°C. CM was collected and concentrated with StrataResin (Stratagene). Bound proteins were released with Laemli containing β-mercaptoethanol and the remaining cell layer was also harvested. Both cell layer and CM fraction proteins were resolved by 4–12% gradient SDS–PAGE (Invitrogen).

Cleavage of matrix-incorporated TSP1 by ADAMTS1

HUVEC (VEC) were grown to confluency for several days. The cell layer was removed from the established matrix by incubating with cold 0.1% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate, 2 mM EDTA (Skill et al, 2004). The remaining matrix was treated with ADAMTS1 or vehicle in DMEM for 2 h at 37°C. Subsequently, the supernatant was collected and concentrated. The remaining matrix was solubilized with Laemli.

Isolation of mouse endothelial cells

Lungs were removed from 8 to 10 weeks old TSP1+/+ and TSP1−/− littermates. After mincing, tissue was incubated in serum-free media containing collagenase 1 mg/ml and dispase II 2 mg/ml under constant agitation for 30 min. Suspensions were stained with anti-PECAM-PE (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and CD45-FITC conjugated (BD Biosciences) for 1 h at 4°C and sorted subsequently using a FACS Star plus cell sorter (BD Biosciences).

Cell proliferation

Endothelial cells were quiesced by culturing postconfluency in DMEM with 0.2% FBS (16–24 h). Cells were then seeded onto 24-well plates in the presence of 0.2% serum, and subsequently stimulated with VEGF (200 ng/ml) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and/or FGF-2 (R&D Systems) (4 ng/ml), and treated with vehicle, TSP1 (2.5 μg/ml), 36 kDa TSP1 (0.66 μg/ml), 110 kDa TSP1 (2 μg/ml), or ADAMTS1 (1 μg/ml) and incubated for 10–14 h followed by a 10 h pulse with 1 μCi/ml of [6–3H]-thymidine (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Subsequently, cells were fixed with 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (Fisher Scientific), solubilized in scintillation fluid and counted with a Microbeta Trilux 1450 scintillation counter (Perkin Elmer, Wellesley, MA). Experiments were performed three independent times in triplicates and [6-3H]-thymidine incorporation was represented as an average percent of control. Bovine aortic endothelial cells were used between passages 5–7. Mouse lung endothelial cells were used between passages 3–6.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jack Lawler for kindly providing purified thrombospondin and TSP1−/− mice, Liman Zhao for mouse colony husbandry, and members of the Arispe Lab for comments and discussions. The UCLA Functional Proteomics Center was established and equipped by a grant to UCLA from the WM Keck Foundation. This study was supported by funds from the National Institutes of Health (CA65624, CA77420 and HL54462). Nathan Lee was supported by the Vascular Biology Training grant at UCLA (HL69766).

References

- Agah A, Kyriakides TR, Lawler J, Bornstein P (2002) The lack of thrombospondin-1 (TSP1) dictates the course of wound healing in double-TSP1/TSP2-null mice. Am J Pathol 161: 831–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annis DS, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Mosher DF (2006) Function-blocking antithrombospondin-1 monoclonal antibodies. J Thromb Haemost 4: 459–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apte SS (2004) A disintegrin-like and metalloprotease (reprolysin type) with thrombospondin type 1 motifs: the ADAMTS family. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 36: 981–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein P (1992) Thrombospondins: structure and regulation of expression. FASEB J 6: 3290–3299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein P, Kyriakides TR, Yang Z, Armstrong LC, Birk DE (2000) Thrombospondin 2 modulates collagen fibrillogenesis and angiogenesis. J Invest Dermatol Symp Proc 5: 61–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada MJ, Sipes JM, Krutzsch HC, Yurchenco PD, Annis DS, Mosher DF, Roberts DD (2003) Recognition of the N-terminal modules of thrombospondin-1 and thrombospondin-2 by alpha6beta1 integrin. J Biol Chem 278: 40679–40687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada MJ, Zhou L, Sipes JM, Zhang J, Krutzsch HC, Iruela-Arispe ML, Annis DS, Mosher DF, Roberts DD (2004) Alpha4beta1 integrin mediates selective endothelial cell responses to thrombospondins 1 and 2 in vitro and modulates angiogenesis in vivo. Circ Res 94: 462–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canals F, Colome N, Ferrer C, Plaza-Calonge Mdel C, Rodriguez-Manzaneque JC (2006) Identification of substrates of the extracellular protease ADAMTS1 by DIGE proteomic analysis. Proteomics 6 (Suppl 1): S28–S35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Ji RW, Davidson D, Schaller J, Marti D, Sohndel S, McCance SG, O'Reilly MS, Llinas M, Folkman J (1996) Kringle domains of human angiostatin. Characterization of the anti-proliferative activity on endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 271: 29461–29467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford SE, Stellmach V, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Ribeiro SM, Lawler J, Hynes RO, Boivin GP, Bouck N (1998) Thrombospondin-1 is a major activator of TGF-beta1 in vivo. Cell 93: 1159–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DW, Pearce SF, Zhong R, Silverstein RL, Frazier WA, Bouck NP (1997) CD36 mediates the in vitro inhibitory effects of thrombospondin-1 on endothelial cells. J Cell Biol 138: 707–717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z, Kumar R, Yang X, Fidler IJ (1997) Macrophage-derived metalloelastase is responsible for the generation of angiostatin in Lewis lung carcinoma. Cell 88: 801–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J (2004) Role of oligomerization domains in thrombospondins and other extracellular matrix proteins. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 36: 997–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari do Outeiro-Bernstein MA, Nunes SS, Andrade AC, Alves TR, Legrand C, Morandi V (2002) A recombinant NH(2)-terminal heparin-binding domain of the adhesive glycoprotein, thrombospondin-1, promotes endothelial tube formation and cell survival: a possible role for syndecan-4 proteoglycan. Matrix Biol 21: 311–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreras M, Felbor U, Lenhard T, Olsen BR, Delaisse J (2000) Generation and degradation of human endostatin proteins by various proteinases. FEBS Lett 486: 247–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther W, Skaftnesmo KO, Arnold H, Bjerkvig R, Terzis AJ (2005) Distribution patterns of the anti-angiogenic protein ADAMTS-1 during rat development. Acta Histochem 107: 121–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hangai M, Kitaya N, Xu J, Chan CK, Kim JJ, Werb Z, Ryan SJ, Brooks PC (2002) Matrix metalloproteinase-9-dependent exposure of a cryptic migratory control site in collagen is required before retinal angiogenesis. Am J Pathol 161: 1429–1437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iruela-Arispe ML, Liska DJ, Sage EH, Bornstein P (1993) Differential expression of thrombospondin 1, 2, and 3 during murine development. Dev Dyn 197: 40–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iruela-Arispe ML, Lombardo M, Krutzsch HC, Lawler J, Roberts DD (1999) Inhibition of angiogenesis by thrombospondin-1 is mediated by 2 independent regions within the type 1 repeats. Circulation 100: 1423–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez B, Volpert OV, Crawford SE, Febbraio M, Silverstein RL, Bouck N (2000) Signals leading to apoptosis-dependent inhibition of neovascularization by thrombospondin-1. Nat Med 6: 41–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalluri R (2003) Basement membranes: structure, assembly and role in tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer 3: 422–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krampert M, Kuenzle S, Thai SN, Lee N, Iruela-Arispe ML, Werner S (2005) ADAMTS1 proteinase is up-regulated in wounded skin and regulates migration of fibroblasts and endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 280: 23844–23852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krutzsch HC, Choe BJ, Sipes JM, Guo N, Roberts DD (1999) Identification of an alpha(3)beta(1) integrin recognition sequence in thrombospondin-1. J Biol Chem 274: 24080–24086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuno K, Matsushima K (1998) ADAMTS-1 protein anchors at the extracellular matrix through the thrombospondin type I motifs and its spacing region. J Biol Chem 273: 13912–13917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuno K, Okada Y, Kawashima H, Nakamura H, Miyasaka M, Ohno H, Matsushima K (2000) ADAMTS-1 cleaves a cartilage proteoglycan, aggrecan. FEBS Lett 478: 241–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvansakul M, Adams JC, Hohenester E (2004) Structure of a thrombospondin C-terminal fragment reveals a novel calcium core in the type 3 repeats. EMBO J 23: 1223–1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler J (2000) The functions of thrombospondin-1 and-2. Curr Opin Cell Biol 12: 634–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler J (2002) Thrombospondin-1 as an endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis and tumor growth. J Cell Mol Med 6: 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler J, Cohen AM, Chao FC, Moriarty DJ (1986a) Thrombospondin in essential thrombocythemia. Blood 67: 555–558 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler J, Connolly JE, Ferro P, Derick LH (1986b) Thrombin and chymotrypsin interactions with thrombospondin. Ann NY Acad Sci 485: 273–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler J, Detmar M (2004) Tumor progression: the effects of thrombospondin-1 and -2. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 36: 1038–1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler J, Sunday M, Thibert V, Duquette M, George EL, Rayburn H, Hynes RO (1998) Thrombospondin-1 is required for normal murine pulmonary homeostasis and its absence causes pneumonia. J Clin Invest 101: 982–992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee NV, Rodriguez-Manzaneque JC, Thai SN, Twal WO, Luque A, Lyons KM, Argraves WS, Iruela-Arispe ML (2005a) Fibulin-1 acts as a cofactor for the matrix metalloprotease ADAMTS-1. J Biol Chem 280: 34796–34804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Jilani SM, Nikolova GV, Carpizo D, Iruela-Arispe ML (2005b) Processing of VEGF-A by matrix metalloproteinases regulates bioavailability and vascular patterning in tumors. J Cell Biol 169: 681–691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque A, Carpizo DR, Iruela-Arispe ML (2003) ADAMTS1/METH1 inhibits endothelial cell proliferation by direct binding and sequestration of VEGF165. J Biol Chem 278: 23656–23665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misenheimer TM, Huwiler KG, Annis DS, Mosher DF (2000) Physical characterization of the procollagen module of human thrombospondin 1 expressed in insect cells. J Biol Chem 275: 40938–40945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittaz L, Russell DL, Wilson T, Brasted M, Tkalcevic J, Salamonsen LA, Hertzog PJ, Pritchard MA (2004) Adamts-1 is essential for the development and function of the urogenital system. Biol Reprod 70: 1096–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott JD, Werb Z (2004) Regulation of matrix biology by matrix metalloproteinases. Curr Opin Cell Biol 16: 558–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-Ullrich JE, Gurusiddappa S, Frazier WA, Hook M (1993) Heparin-binding peptides from thrombospondins 1 and 2 contain focal adhesion-labilizing activity. J Biol Chem 268: 26784–26789 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicosia RF, Tuszynski GP (1994) Matrix-bound thrombospondin promotes angiogenesis in vitro. J Cell Biol 124: 183–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary JM, Hamilton JM, Deane CM, Valeyev NV, Sandell LJ, Downing AK (2004) Solution structure and dynamics of a prototypical chordin-like cysteine-rich repeat (von Willebrand Factor type C module) from collagen IIA. J Biol Chem 279: 53857–53866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly MS, Wiederschain D, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Folkman J, Moses MA (1999) Regulation of angiostatin production by matrix metalloproteinase-2 in a model of concomitant resistance. J Biol Chem 274: 29568–29571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Manzaneque JC, Lane TF, Ortega MA, Hynes RO, Lawler J, Iruela-Arispe ML (2001) Thrombospondin-1 suppresses spontaneous tumor growth and inhibits activation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and mobilization of vascular endothelial growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 12485–12490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Manzaneque JC, Milchanowski AB, Dufour EK, Leduc R, Iruela-Arispe ML (2000) Characterization of METH-1/ADAMTS1 processing reveals two distinct active forms. J Biol Chem 275: 33471–33479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Manzaneque JC, Westling J, Thai SN, Luque A, Knauper V, Murphy G, Sandy JD, Iruela-Arispe ML (2002) ADAMTS1 cleaves aggrecan at multiple sites and is differentially inhibited by metalloproteinase inhibitors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 293: 501–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DL, Doyle KM, Ochsner SA, Sandy JD, Richards JS (2003) Processing and localization of ADAMTS-1 and proteolytic cleavage of versican during cumulus matrix expansion and ovulation. J Biol Chem 278: 42330–42339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandy JD, Thompson V, Doege K, Verscharen C (2000) The intermediates of aggrecanase-dependent cleavage of aggrecan in rat chondrosarcoma cells treated with interleukin-1. Biochem J 351: 161–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandy JD, Westling J, Kenagy RD, Iruela-Arispe ML, Verscharen C, Rodriguez-Mazaneque JC, Zimmermann DR, Lemire JM, Fischer JW, Wight TN, Clowes AW (2001) Versican V1 proteolysis in human aorta in vivo occurs at the Glu441-Ala442 bond, a site that is cleaved by recombinant ADAMTS-1 and ADAMTS-4. J Biol Chem 276: 13372–13378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindo T, Kurihara H, Kuno K, Yokoyama H, Wada T, Kurihara Y, Imai T, Wang Y, Ogata M, Nishimatsu H, Moriyama N, Oh-hashi Y, Morita H, Ishikawa T, Nagai R, Yazaki Y, Matsushima K (2000) ADAMTS-1: a metalloproteinase-disintegrin essential for normal growth, fertility, and organ morphology and function. J Clin Invest 105: 1345–1352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skill NJ, Johnson TS, Coutts IG, Saint RE, Fisher M, Huang L, El Nahas AM, Collighan RJ, Griffin M (2004) Inhibition of transglutaminase activity reduces extracellular matrix accumulation induced by high glucose levels in proximal tubular epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 279: 47754–47762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit M, Riccardi L, Velasco P, Brown LF, Hawighorst T, Bornstein P, Detmar M (1999) Thrombospondin-2: a potent endogenous inhibitor of tumor growth and angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 14888–14893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit M, Velasco P, Riccardi L, Spencer L, Brown LF, Janes L, Lange-Asschenfeldt B, Yano K, Hawighorst T, Iruela-Arispe L, Detmar M (2000) Thrombospondin-1 suppresses wound healing and granulation tissue formation in the skin of transgenic mice. EMBO J 19: 3272–3282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan K, Duquette M, Liu JH, Dong Y, Zhang R, Joachimiak A, Lawler J, Wang JH (2002) Crystal structure of the TSP-1 type 1 repeats: a novel layered fold and its biological implication. J Cell Biol 159: 373–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan K, Duquette M, Liu JH, Zhang R, Joachimiak A, Wang JH, Lawler J (2006) The structures of the thrombospondin-1 N-terminal domain and its complex with a synthetic pentameric heparin. Structure 14: 33–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taraboletti G, Belotti D, Borsotti P, Vergani V, Rusnati M, Presta M, Giavazzi R (1997) The 140-kilodalton antiangiogenic fragment of thrombospondin-1 binds to basic fibroblast growth factor. Cell Growth Differ 8: 471–479 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thai SN, Iruela-Arispe ML (2002) Expression of ADAMTS1 during murine development. Mech Dev 115: 181–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolsma SS, Volpert OV, Good DJ, Frazier WA, Polverini PJ, Bouck N (1993) Peptides derived from two separate domains of the matrix protein thrombospondin-1 have anti-angiogenic activity. J Cell Biol 122: 497–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez F, Hastings G, Ortega MA, Lane TF, Oikemus S, Lombardo M, Iruela-Arispe ML (1999) METH-1, a human ortholog of ADAMTS-1, and METH-2 are members of a new family of proteins with angio-inhibitory activity. J Biol Chem 274: 23349–23357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westling J, Fosang AJ, Last K, Thompson VP, Tomkinson KN, Hebert T, McDonagh T, Collins-Racie LA, LaVallie ER, Morris EA, Sandy JD (2002) ADAMTS4 cleaves at the aggrecanase site (Glu373–Ala374) and secondarily at the matrix metalloproteinase site (Asn341–Phe342) in the aggrecan interglobular domain. J Biol Chem 277: 16059–16066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Rodriguez D, Petitclerc E, Kim JJ, Hangai M, Moon YS, Davis GE, Brooks PC, Yuen SM (2001) Proteolytic exposure of a cryptic site within collagen type IV is required for angiogenesis and tumor growth in vivo. J Cell Biol 154: 1069–1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]