Abstract

Using two-dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis, we show that mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) replication of birds and mammals frequently entails ribonucleotide incorporation throughout the lagging strand (RITOLS). Based on a combination of two-dimensional agarose gel electrophoretic analysis and mapping of 5′ ends of DNA, initiation of RITOLS replication occurs in the major non-coding region of vertebrate mtDNA and is effectively unidirectional. In some cases, conversion of nascent RNA strands to DNA starts at defined loci, the most prominent of which maps, in mammalian mtDNA, in the vicinity of the site known as the light-strand origin.

Keywords: DNA, mitochondria, mtDNA, replication, vertebrate

Introduction

The most widespread mechanism of DNA replication entails concurrent leading and lagging-strand DNA synthesis (Kornberg and Baker, 1992). RNA oligonucleotides are required for multiple priming events on the lagging strand, whereas the leading strand requires only a single priming event, which may involve either RNA or protein, this asymmetry reflecting the antiparallel arrangement of double-stranded DNA (Watson and Crick, 1953).

Animal mitochondrial DNAs (mtDNA) are covalently closed circular molecules of approximately 16 kb. They encode essential polypeptides of the oxidative phosphorylation system, and the ribosomal and transfer RNAs necessary for their synthesis. Replication of mammalian mtDNA was long believed to occur via continuous, but asynchronous synthesis of each strand, rather than by a conventional strand-coupled mechanism. The model was initially elaborated on the basis of electron microscopy, which revealed partially single-stranded replication intermediates (RIs) (Robberson et al, 1972). Prominent 5′ ends were mapped to two sites: those on the putative leading (heavy) strands to a specific area of the major non-coding region (NCR) (Crews et al, 1979), designated the origin of heavy strand replication (OH), and those on the presumed lagging-strand to a short spacer region in a cluster of five tRNA genes (Kang et al, 1997; Tapper and Clayton, 1982), named the origin of light-strand replication (OL). Many molecules of mammalian mtDNA contain a short triple-stranded region, or D-loop (Arnberg et al, 1971; Kasamatsu et al, 1971). The third strand of the D-loop, 7S DNA, is readily displaced by heating, it spans much of the NCR and its 5′ end coincides with OH. This led to the proposal that 7S DNA represented stalled or aborted RIs.

More recently, RIs with properties of conventional strand-coupled DNA synthesis, but inconsistent with the strand-asynchronous model, were detected in mammalian mitochondria using two dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis (2D-AGE) (Holt et al, 2000). These were shown to initiate across a broad zone (ori-Z) spanning several kilobases in solid tissues (Bowmaker et al, 2003), but in a narrower zone within the NCR in cultured cells re-amplifying mtDNA after drug-induced mtDNA depletion (Yasukawa et al, 2005). In addition, RIs with extensive RNA patches on the L-strand were detected (Yang et al, 2002). The latter were demonstrated to be labile to RNA loss during extraction, potentially accounting for the partially single-stranded mitochondrial RIs detected previously by electron microscopy (Robberson et al, 1972), and again recently by atomic force microscopy (AFM) (Brown et al, 2005).

In the present study, we set out to determine the precise structure of ribonucleotide-rich RIs. Remarkably, we found that RNA can extend across one entire nascent strand of mtDNA, prior to lagging strand DNA synthesis.

Results

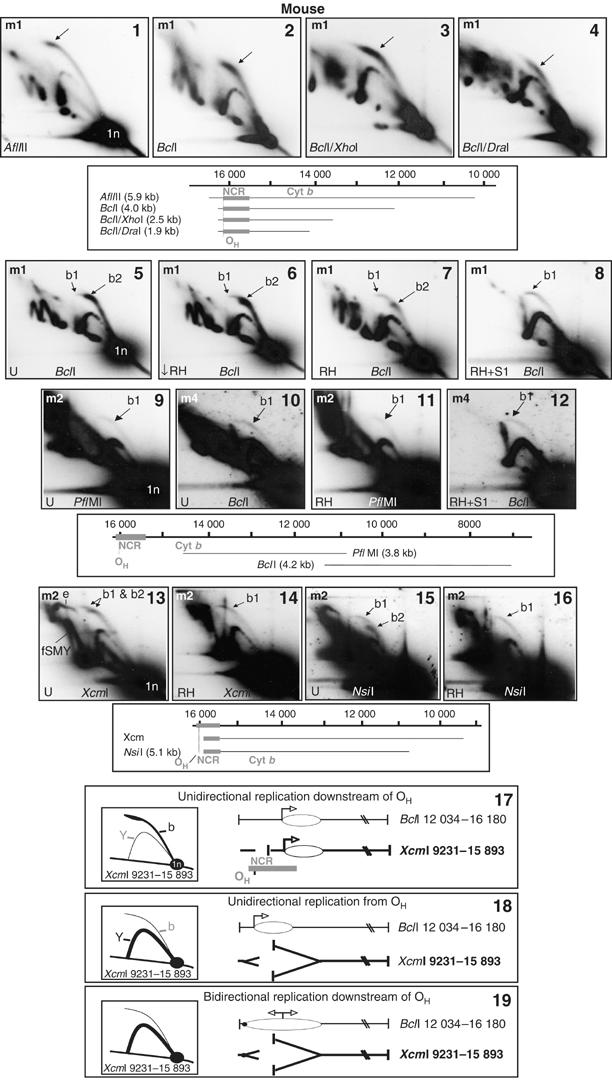

Replicating circles of mtDNA after restriction digestion are indicative of ribonucleotide incorporation at sites across much of the mitochondrial genome

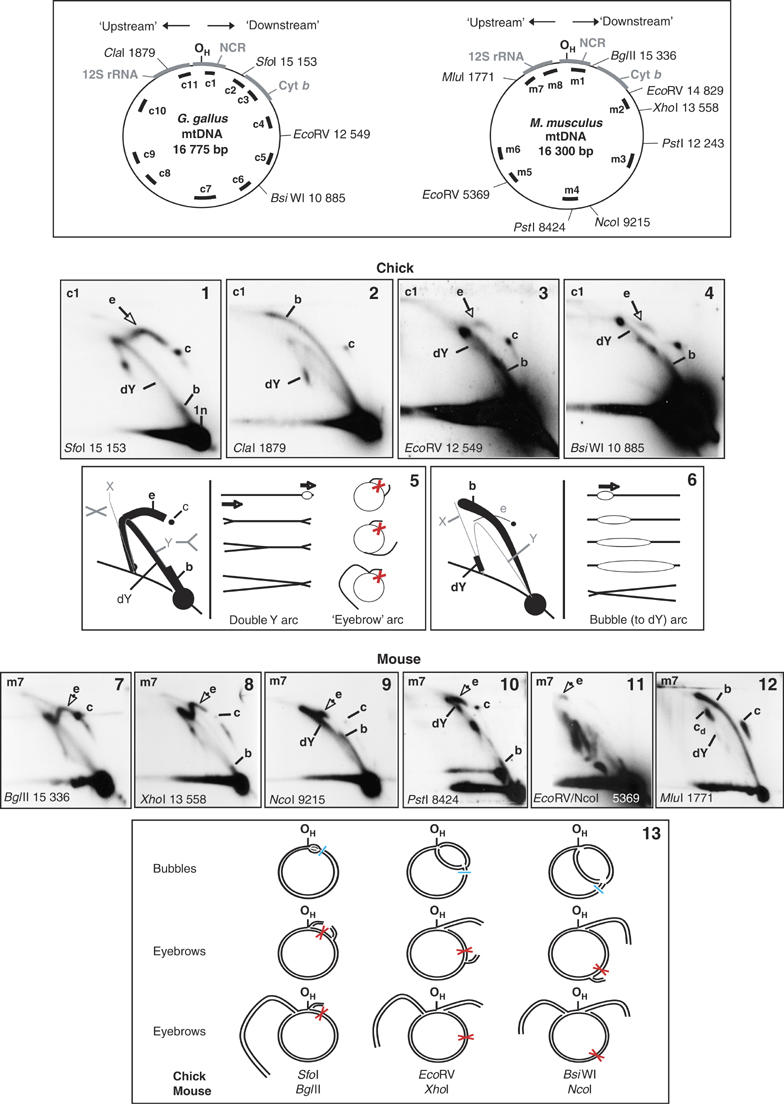

The existence of RNA patches on the L-strand of replicating mtDNA (Yang et al, 2002) predicts one branch of a replication bubble will not be cleaved by a restriction enzyme, wherever the site coincides with an RNA patch. For restriction enzymes cutting mtDNA at one site only, ribonucleotide blockage will produce replicating circles of mtDNA, analogous to uncut circular molecules with a broken bubble (Lucas et al, 2001; Martin-Parras et al, 1992, 1998). After digestion of chick liver mtDNA with SfoI, which cuts exclusively at nucleotides (nt) 15 153, two major arcs of RIs were apparent a double Y arc and an arc of replicating circles, or ‘eyebrow' (Figure 1(1), and interpreted in Figure 1(5)). Cleavage on the other side of the major NCR at nt 1879, gave a quite different pattern of RIs, there was a prominent, extensive bubble arc consistent with a theta mechanism of replication, and very few uncut circles (Figure 1(2), and interpreted in Figure 1(6)). An eyebrow was again evident when the DNA was digested with restriction enzymes cutting uniquely at nt 12 549 or 10 885 (Figure 1(3 and 4), respectively) indicating that these sites are also frequently blocked in replicating molecules. Analysis of mouse liver mtDNA produced similar results; BglII cutting once close to the cytochrome b gene end of the mouse NCR yielded a prominent eyebrow (Figure 1(7)) as did another enzyme cutting 2 kb away in the coding region (Figure 1(8)); the eyebrow was significantly shorter yet still prominent when mouse liver mtDNA was digested with NcoI, which cuts over 6 kb downstream of the NCR (Figure 1(9)). Digesting mouse mtDNA with PstI, which cuts duplex DNA at two sites also yielded an eyebrow (Figure 1(10)), which is the result of restriction site blockage at both nts 12 243 and 8424 on the same branch of a replicating molecule. Cleavage of mouse mtDNA at nts 14 829, 9215 and 5369 yielded a much weaker eyebrow (Figure 1(11)), whereas no appreciable eyebrow was associated with MluI digested mouse mtDNA cut at nt 1771 (Figure 1(12)). Eyebrows were evident in chick mtDNA after digestion with enzymes expected to cleave at nts 3512, 2843 and 1600 among other sites (Supplementary Figure 1(1–3)). RNase H treatment modified eyebrows (Supplementary Figure 1(5–8)), consistent with the idea that the failure to cleave at the various restriction sites is attributable to ribonucleotide incorporation.

Figure 1.

Restriction site blockage in mtDNA of chick and mouse. Schematic maps of Gallus gallus and Mus musculus mitochondrial genomes, with restriction sites and probes, appear at the top of the figure. The position of the site designated as the heavy-strand origin of replication (OH) and the major NCR are marked on the maps together with the positions of the cytochrome b (Cyt b) and 12S rRNA genes (12S rRNA). ‘Downstream' refers to events and loci on the Cyt b gene side of OH, whereas ‘upstream' refers to the 12S rDNA side of OH. 2D-AGE gels are as follows: Panels 1–4, chick liver mtDNA cleaved with the restriction enzymes indicated and hybridized with probe c1. Panel 5, interpretation of panel 1, SfoI-cuts chick liver mtDNA at a single site in the genome, at nt 15 153. The short length and low trajectory of the bubble arc (b) rule out a bidirectional origin near the center of the genome-length fragment ∼nt 9000, since this would produce a rather similar pattern to the ClaI digest (Panel 2, and interpreted in panel 6). Instead, to reconcile both patterns of intermediates (panels 1 and 2), the origin must lie close to one end of the fragment, and must also be coincident or adjacent to the definitive terminus, as illustrated (panels 5 and 6). Cleavage of a bubble on both branches will convert a replicating circle to a linear molecule with a fork at either end. In the case of SfoI-digested chick liver mtDNA, the bubble arc is short; hence, the restriction site must lie close to the origin; moreover, most of the molecule must be copied by a single active fork, as two active forks would produce a double Y arc ending near the apex of an X arc (well above the linear duplex arc). Thus, the prominent Y-like arc (panel 1) must be a double Y arc (dY), with a static fork close to one end of the fragment (see also (Schvartzman et al, 1993). The other prominent arc (e) lying above the position of a standard Y arc is inferred to be an arc of circular molecules of increasing size (an eyebrow), as it corresponds approximately to previously described arcs of replicating circular molecules (Brewer et al, 1988; Belanger et al, 1996). As illustrated, it is a predicted product of site blockage (red cross) on one branch of a theta structure. The position of open/nicked circular mtDNA (c) was determined by separating uncut mtDNA by 2D-AGE (data not shown). Panel 6: interpretation of panel 2. The unique ClaI site lies on the other side of the NCR from the SfoI site at nt 1879, in chick mtDNA. A small amount of uncut circles (c) remain. The bubble arc (b) extends over almost the entire length of the fragment, with a short double Y arc (dY) and a faint Y arc also visible. This is consistent with unidirectional replication originating from a site near the (Cyt b gene) end of the fragment, as illustrated. A bidirectional terminus near one end of the fragment, adjacent to an initiation zone, would give the same pattern. No eyebrow arc was evident; however, in the case of ClaI such an arc would be short, corresponding to only 6% of a full-length eyebrow arc and could well coincide with the bubble arc; moreover, as it represents the final stages of replication it might be short-lived. Panels 7–12, mouse liver mtDNA cut with the restriction enzymes indicated, and hybridized with probe m7. Site coordinates are either the unique sites of digestion, or (panels 10 and 11) the site of digestion furthest from the Cyt b end of the D-loop, as this is indicative of the distance travelled (clockwise) by a unidirectional fork starting from the NCR, see also panel 13. 1n—unit length fragment, b—bubble arc, dY—double Y arc, c—circular monomers, e—eyebrow arc, cd—circular dimers (the end of an eyebrow arc). Eyebrows correspond to replicating circular molecules, and have previously been associated with both theta and rolling circle replication (Belanger et al, 1996; Preiser et al, 1996; Brewer et al, 1988). Panel 13—Interpretation of the 2D-AGE data, consistent with a unidirectional origin or terminus at OH and restriction site blockage (indicated by a red cross) at several points on one strand of replicating mtDNA molecules. Cyan bars indicate restriction sites that the advancing replication fork has not yet reached, generating bubble arcs. (For colour figure see online.)

Mapping the zone of ribonucleotide incorporation using truncated eyebrows

Unlike conventional eyebrows, those associated with mtDNA replication migrated on 2D gels with a gap of variable size visible between simple circles and the start of the eyebrow (Figure 1(1–4) and (7–9)). The size of the gap is predicted to correspond with the distance the replication fork(s) has travelled before reaching the restriction site and thereby provides information on the origin, direction and terminus of replication (schematically illustrated in Figure 1(13)). In mouse, the gap between eyebrow and circular monomers was shortest in the case of BglII (Figure 1(7)), whose one site in the mouse mitochondrial genome lies just beyond the NCR. XhoI cuts approximately 2 kb from the NCR and here the gap was noticeably larger (Figure 1(8)); digestion with NcoI, cleaving 6 kb downstream of the NCR, eliminated approximately half the eyebrow (Figure 1(9)). These results map the start of the zone of ribonucleotide incorporation close to the BglII site, extending around a substantial portion of the genome. Note also that the distribution of digestion sites generating prominent bubble arcs and double-Y arcs is also consistent with initiation and termination of replication in the region where ribonucleotide incorporation begins, although these data alone cannot discriminate between unidirectional replication initiating in the NCR, upstream of nt 15 336, and bidirectional replication initiating close to the NCR accompanied by fork arrest and termination at or close to OH.

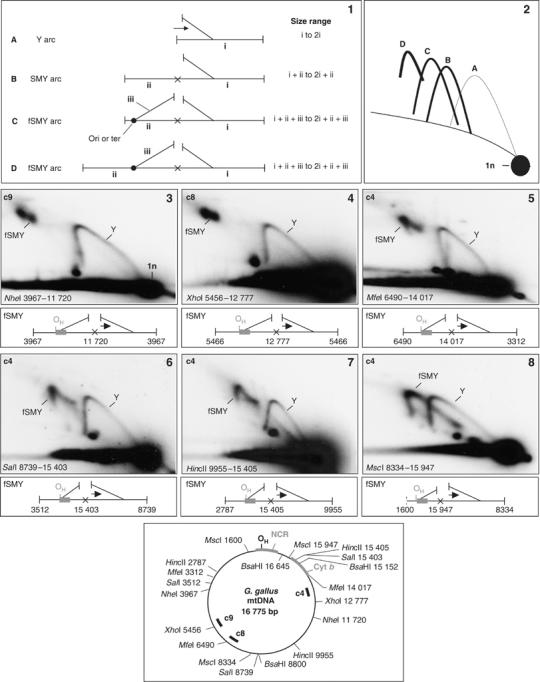

Slow-moving Y-like arcs reveal the fine distribution of ribonucleotide-blocked restriction sites in the genome

We next considered the expected outcome of restriction site blockage on RIs cut additionally within the region not yet replicated. If an advancing replisome incorporates ribonucleotides at a single site on one nascent strand and the flanking sites are cleaved, this will result in two fragments remaining joined, thereby creating a slow moving Y-like arc (SMY, species B, Figure 2(1) and arc B in Figure 2(2)). If, however, the adjacent fragment contains a unidirectional origin (or terminus), the RI will contain a second, static, branch (species C and D, Figure 2(1)), altering the size and mobility of the RIs and resulting in a distinct type of SMY arc that never meets the linear diagonal (fSMY, flying SMY arc). The length of the static branch, in conjunction with its position within the fragment, determines how close to the linear arc the fSMY arc begins and ends. A terminus or unidirectional origin close to one end of the restriction fragment (Figure 2(1-C)) is predicted to form an arc close to the linear duplex arc (Figure 2(2, arc C)), whereas an origin located centrally within a fragment (Figure 2 (1-D)), will yield an arc well above the linear duplex arc (Figure 2(2), arc D). Analysis of digests carried out with restriction enzymes cutting chick mtDNA twice or more demonstrated that all fragments immediately adjacent to the cytochrome b end of the NCR produced fSMY arcs (slow-moving arcs which both begin and end at positions above the linear duplex arc), indicating blocked sites at nts 11 720, 12 777, 14 017, 15 403, 15 405, 15 947 (Figure 2(3–8)) and 16 645 (Supplementary Figure 2(1)). Note that the fSMY arc moves inexorably closer to the linear arc as the restriction site approaches the NCR (nts 1–1227); that is, as the static branch shortens (Figure 2(3–8), and Supplementary Figure 2(1)). These results are in agreement with the eyebrow data, mapping the unidirectional origin (or terminus) of ribonucleotide-rich replication close to the NCR (<1 kb upstream of nt 16 645 in the case of chick).

Figure 2.

Mapping of the origin/terminus of replication by slow-moving Y-like arcs. Panels 1 and 2—diagrammatic explanation of patterns of 2D-AGE arcs resulting from ribonucleotide blockage of restriction sites. 1A and 2A: a uniform replication fork (Y) arc results when a replisome enters one end of a restriction fragment (length i) and proceeds to the other end without impediment; arrow indicates direction of replication. 1B and 2B: Where a restriction site is blocked by ribonucleotide incorporation on one strand (denoted by a cross), the adjacent fragment (length ii) remains joined, creating a slow-moving Y-like arc, SMY. 1C–D and 2C–D: If the adjacent fragment contains a replication terminus (ter) or unidirectional origin (ori), then the resulting series of replication intermediates will contain two junctions, one active, the other static. These form a distinct type of ‘flying' slow-moving Y-like arc (fSMY), whose ends do not meet the diagonal of linear molecules. The length of the static branch (iii) relative to that of the fragment (ii) to which it is joined determines how far above the linear diagonal the fSMY arc lies; arc 2D starts and ends well above the linear diagonal, whereas fSMY arc 2C lies much closer to it. Panels 3–8: 2D-AGE analysis of chick liver mtDNA digested with NheI, XhoI, MfeI, SalI, HincII and MscI, respectively; nucleotide coordinates define the unit-length linear fragment detected in each case. A representative intermediate of each of the fSMY arcs is depicted beneath the gel images. Crosses are blocked restriction sites; arrows indicate direction of movement of the growing fork, the other fork is static; gray-filled box—NCR. Radiolabeled probes used to detect mtDNA fragments are indicated at the top left of panels 3–8, and their approximate location is indicated on the schematic map at the base of the figure, together with relevant restriction sites. HincII and MscI also cut elsewhere, but only sites relevant to the arcs detected are shown.

The slow-moving Y-like arcs migrating entirely above the linear duplex arc (fSMY arcs) were, like eyebrows, found to be RNase H sensitive (Supplementary Figure 2(2–5)), suggesting they arise by the same mechanism of replication. Based on the relative signal strengths of fSMY to simple Y arcs (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 2), and of eyebrow to Y/double Y arcs (Figure 1), the proportion of replicating molecules exhibiting extensive ribonucleotide incorporation was approximately 50% in chick liver and even greater in mouse.

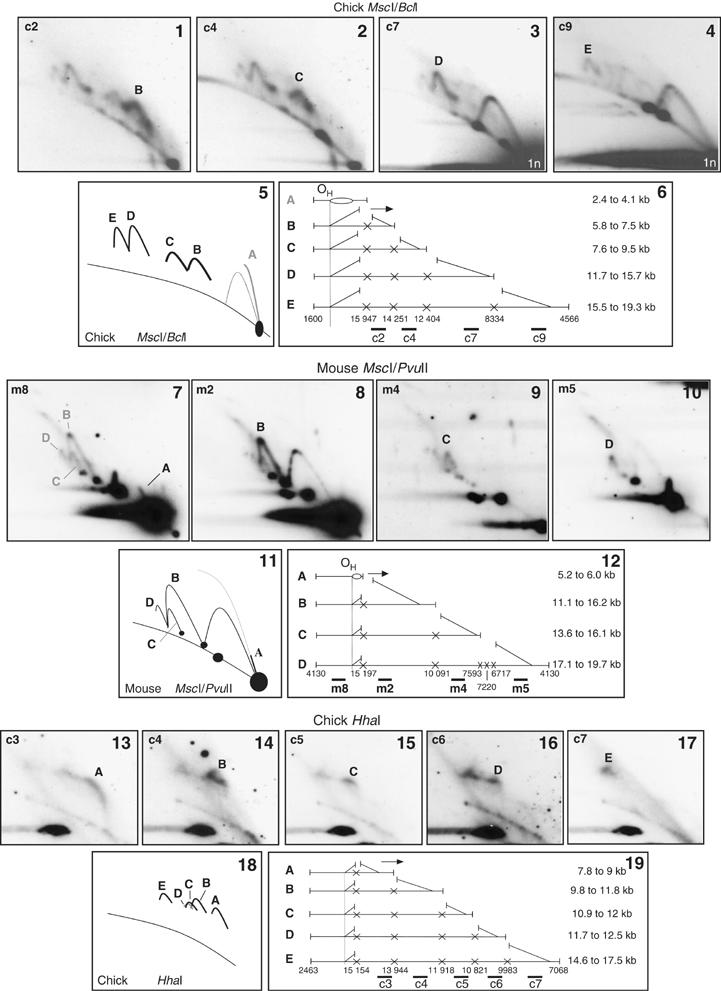

The patterns of fSMY arcs produced by double-digestion of either chick (Figure 3(1–4), MscI/BclI digests) or mouse liver mtDNA (Figure 3(7–10), MscI/PvuII digests) are consistent with an origin of replication within or close to the NCR, giving rise to extensive ribonucleotide incorporation on one strand (as illustrated in Figure 3(5, 6 and 11, 12), respectively). The observed slow-moving arcs imply that multiple restriction sites are blocked on the same branch of one molecule. These particular arcs could not be generated by initiation within the coding region. The generation of fSMY arcs is also not attributable to single-stranded DNA at the restriction sites, based on the following arguments. fSMY arcs were generated also by digestion with HhaI (Figure 3(13–17)) or AccI (Supplementary Figure 3(1)), restriction enzymes that efficiently cleave their recognition sites even in single-stranded DNA. The sizes of the fSMY arcs are inconsistent with the presence of extensive single-stranded regions (Supplementary Figure 3(4 and 5)). Finally, fSMY arcs (Supplementary Figure 2(3 and 5)) as well as eyebrows (Supplementary Figure 1(6 and 8)) were grossly modified by RNase H.

Figure 3.

Restriction site blockage at multiple sites of replicating Gallus gallus and Mus musculus mtDNA. 2D-AGE gels of (panels 1–4 and 13–17) chick and (panels 7–10) mouse liver mtDNA, digested and probed as indicated. The various arcs detected are labeled in panels 5, 11 and 18, and explained diagrammatically in panels 6, 12 and 19. BclI plus MscI digestion of G. gallus mtDNA is predicted to cleave at six sites. Continuous ribonucleotide incorporation on one strand, with a terminus or unidirectional origin at OH, predicts a series of fSMY arcs as shown, with uncleaved sites denoted by crosses. Similarly, MscI plus PvuII digestion of mouse liver mtDNA produces the predicted set of fSMY arcs (panels 7–12). The same applies to digestion with HhaI (panels 13–17), which also cuts its recognition site in either single-stranded or double stranded DNA. See also Supplementary Figure 3.

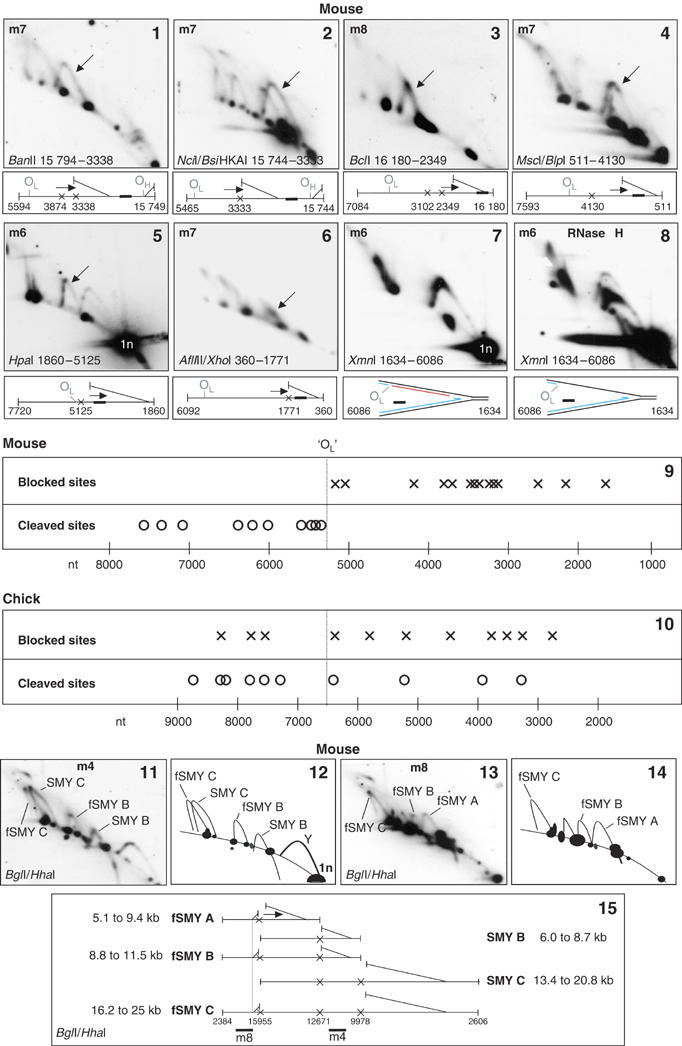

In mouse liver, fragments encompassing the final one-third of the mitochondrial genome gave different patterns. Some probes detected prominent SMY arcs (Figure 4(1–6)) whereas others yielded a combination of an RNase H-sensitive simple Y arc and a partial fSMY arc (Figure 4(7 and 8)). Note the inverse relationship: the Y arc is particularly prominent between its apex and 2n, whereas the prominent portion of the fSMY arc is the ascending arm (Figure 4(7)). This last result is consistent with conversion of fSMY species to simple Y-like structures, which necessitates duplex DNA on all branches of the RI at the restriction sites (nt 1634 and 6086). Nevertheless, RNA continues to be incorporated behind the advancing fork, since RNase H causes a partial collapse of most of the Y arc (Figure 4(8), interpreted in Supplementary Figure 4(1)). In other regions of mouse liver mtDNA simple Y arcs were RNase H insensitive (Supplementary Figure 4(4 and 5)). Conflating the data from a number of digests, there appeared to be a marked discontinuity of ribonucleotide content between nucleotides 5125 and 5249. Sites in the 2.5 kb leading up to nt 5249 were frequently cleaved, whereas those at nt 5125 and beyond were predominantly blocked (Figure 4(9)). Such a discontinuity was not seen in the equivalent region of the chick genome where sites were equally likely to be cleaved or blocked (Figure 4(10) and Supplementary Figure 4(9–12)).

Figure 4.

Different distribution of blocked and cleaved sites in mouse and chick liver mitochondrial RIs. 2D-AGE analysis of mouse liver mtDNA, digested and probed as indicated. Nucleotide coordinates indicate the unit-length fragment detected in each case (panels 1–8). The major slow-moving arc detected in each case (arrowed) is diagrammed below panels 1–6, or in panels 12, 14 and 15 (relating to panels 11 and 13). Probes for restriction fragments of mouse mtDNA covering the final one-third of the genome gave rise predominantly to reverse fSMY arcs, where the active fork is advancing on the static branch instead of travelling away from it (panels 1 and 2), SMY arcs (panels 3–6) or partial fSMY arcs and a prominent simple Y arc (panel 7 and Supplementary Figure 4(2)), implying that ribonucleotides continue to be incorporated on one strand at positions far from the putative origin(s) in the NCR, whereas sites in a region closer to the origin are cut. A representative intermediate is depicted below each panel. Red lines—RNA incorporated on lagging strand; X—blocked restriction site. Arrows indicate the direction of fork movement; a broad line marks the approximate position of the probe within the fragment. Panel 9 summarizes the results of these analyses, showing sites predominantly blocked (crosses) or predominantly cleaved (circles) in the RIs detected, these data all relate to fragments where the fork is traversing the final third of the genome. Analyses of the corresponding region of chick liver mtDNA (Supplementary Figure 4(9–12)) revealed interspersion of predominantly blocked and digestible sites, as summarized in Figure 4(10). Unlike mouse, some sites in chick liver were blocked and cleaved in equal measure (e.g. the BsgI site at nt 7608, see Supplementary Figure 4(12)). Vertical broken line indicates OL (nt 5160–5191), which lies between the tRNAAsn and tRNACys genes of mouse mtDNA, or the junction of these genes in chick mtDNA (nt 6540). The prominent Y arc seen for the XmnI fragment nt 1634–6086 (panel 7, interpreted in Supplementary Figure 4(1)) was highly sensitive to RNase H (RH) (panel 8, interpreted in Supplementary Figure 4(8)), indicating that ribonucleotide-rich RIs have duplex DNA behind the advancing fork at nt 6086. Y arcs of equivalent fragments of chick mtDNA were markedly less sensitive to RNase H (e.g. Supplementary Figure 4(14 and 15)). Panels 11–15: detection of both fSMY and SMY arcs in panel 11, whose identity is confirmed by reprobing (panel 13), indicates unidirectional replication (or termination) events to the left of nt 15 955 in mouse liver mtDNA. (For colour figure see online.)

As detailed above, probing for fragments adjacent to and downstream of the NCR yielded fSMY arcs (Figures 2 and 3). However, probing for fragments with a restriction site inside the NCR yielded both SMY and fSMY arcs, for example, BglI/HhaI (Figure 4(11, 12 and 15)). Assignment of the arcs was confirmed by rehybridization with probe m8 (Figure 4(13)) and m1 (data not shown). fSMY arcs B and C (Figure 4(11 and 13)) indicate restriction site blockage at nt 15 955 and on the same branch at nts 12 671 and 9978 (illustrated in Figure 4(15)). This implies ribonucleotide-rich replication frequently initiates upstream of nt 15 955, in mouse, a mere 79 nts from OH. Digestion of chick mtDNA with EcoNI (Supplementary Figure 4(16)) or BspHI (data not shown), and mouse mtDNA with BanII (Supplementary Figure 4(19–21)) produced similar results, indicating frequent site blockage 323, 400 and 285 nts from OH, respectively.

Prominent, RNase-H sensitive ‘clubheaded' initiation arcs are associated with NCR-containing fragments of rodent and chick liver mtDNA

Although previous analysis of mouse liver mtDNA (Bowmaker et al, 2003) revealed bubble arcs indicative of a broad, bidirectional initiation zone (Ori-Z) spanning several kilobases, a very prominent initiation arc whose signal increased towards the apex, was also detected, exclusive to NCR-containing fragments (Figure 5(1–4)). Such ‘clubheaded' initiation arcs are considered diagnostic for a discrete origin or a narrow initiation zone (Kalejta and Hamlin, 1996). Digestion with increasing amounts of RNase H systematically altered the mobility of the clubheaded initiation arc, which appeared progressively to ‘retract' (Figure 5(5–7) and data not shown). RNase H and S1 nuclease treatments revealed a residual, homogeneous, nuclease-resistant and much fainter initiation arc (e.g. Figure 5(8)), similar to those generated by non-NCR-containing fragments from the Ori-Z region (Figure 5(9–12)). Clubheaded initiation arcs associated with NCR-containing fragments of rat and chick mtDNA showed similar properties (Supplementary Figure 5(1–6)). The simplest interpretation is that the same replication mechanism, involving substantial ribonucleotide incorporation, gives rise both to the RNase H-sensitive, clubheaded bubble arcs and to the eyebrow and fSMY arcs documented above. Conversely, the fainter, RNase H-resistant bubble arcs must arise from initiation of conventional strand-coupled replication at sites widely dispersed across the initiation zone (Bowmaker et al, 2003). RNase H-sensitive initiation arcs were seen in NCR-containing fragments whether or not they included OH, although those spanning OH were much more prominent (compare Figure 5(13–16) with 5.1–5.4), suggesting multiple sites of initiation of this type of replication in the NCR (see Figure 5(17–19)).

Figure 5.

RNase H-sensitive ‘clubheaded' initiation arcs localize the origin of ribonucleotide-incorporating replication to the NCR. 2D-AGE analysis of NCR-containing fragments of mouse liver mtDNA, digested with the restriction enzymes and hybridized with probes as indicated, m1 (panels 1–8), m2 (panels 9, 11 and 13–16) or m4 (panels 10 and 12). Diagrams indicating the fragments detected are shown beneath the relevant gel panels. Panels 5–16 were either treated with low levels of RNase H (↓ RH, 0.1 U, 30 min, 37°C), or our standard treatment (RH, 1 U, 30 min, 37°C) or S1 nuclease (S1, 1 U, 60 s, 37°C) or else left untreated with nuclease (U). Mock RNase H treatments or very low doses of RNase H were indistinguishable from untreated samples (data not shown). Bubble arcs are arrowed: b1—RNase H-insensitive bubble arcs detected across the origin zone (Ori-Z); b2—RNase H-sensitive, clubheaded bubble arcs detected only in NCR-containing fragments. See also Supplementary Figure 5. Panels 13–16: a weak RNase H-sensitive initiation arc is associated with fragments of mouse liver mtDNA containing some of the NCR yet lacking OH. Probe m2 was applied to a 2D blot of XcmI digested mouse mtDNA treated without (panel 13) and with (panel 14) RNase H, revealing a 6.65 kb fragment (nt 9231–15 893) including >400 nts of the NCR. Similarly, NsiI fragment nt 10 765–15 909 yielded two initiation arcs (panel 15), only one of which was RNase H resistant (panel 16). The RNase H-sensitive, clubheaded bubble arcs of non OH-containing fragments, (panels 13 and 15), are compatible only with unidirectional replication initiating in the NCR downstream of OH (panel 17). Three panels (17–19) depict alternative hypothetical modes of replication initiation. Panel 17 represents unidirectional replication from the OH-distal end of the NCR; panel 18 shows unidirectional replication from OH; panel 19 represents bidirectional replication from the OH-distal end of the NCR. Of these three modes of initiation, only the one shown in panel 17 is consistent with the initiation arcs seen in panels 13 and 15, as indicated by the hypothetical 2D-AGE gel images shown alongside each model; b—bubble arc; Y—simple replication fork arc. This model, of a fraction of molecules initiating unidirectional replication at the cytochrome b gene end of the NCR, is also consistent with the detection of a cluster of H-strand 5′ ends mapping to the OH-distal end of the NCR (Figure 6(1)).

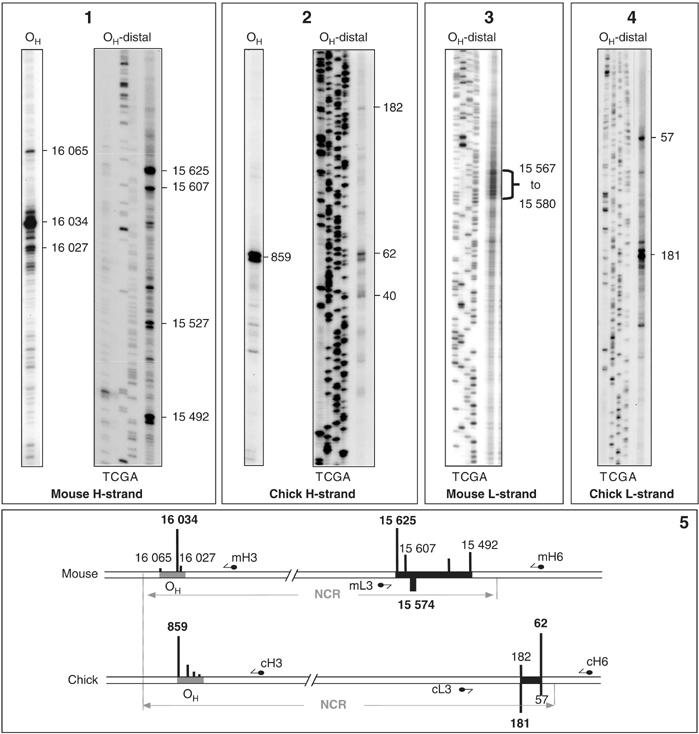

Mapping of free 5′ ends in the NCR of rodent and chick liver mtDNA

Ligation-mediated PCR (LM-PCR) was used to map putative replication-initiation sites in the NCR of mouse and chick liver mtDNA. A small number of prominent H-strand 5′ ends were detected at OH, as well as a second cluster towards the opposite end of the NCR (Figure 6(1 and 2)). Prominent 5′ ends were detected also on the L-strand opposite the latter cluster in chick liver mtDNA samples (Figure 6(4)), and to a lesser extent in mouse liver mtDNA (Figure 6(3)).

Figure 6.

Prominent free 5′ ends map to two regions of the NCR in mouse and chick liver mtDNA. LM-PCR analysis of H-strand 5′ ends in the OH-containing and OH-distal portions of the NCR in mouse (panel 1) and chick (panel 2). Sequencing ladders were used in all cases to identify 5′ ends at the nucleotide level, and only those for the OH-distal portion of the NCR are shown. Screening of the L-strand across the OH-distal region revealed prominent 5′ ends in mouse (panel 3) and chick (panel 4) mtDNA, but not in the OH-containing region (data not shown). Panel 5: schematic linear maps showing locations of major 5′ ends on each strand (from data of panels 1–4). For simplicity, prominent ends within a few nucleotides of each other are conflated into micro-clusters and given a single nucleotide number. Gray and black zones indicate, respectively, the two clusters around OH and the distal portion of the NCR. Short arrows with a filled circle at one end mark the position of labeled primers. Bar heights indicate relative signals for a given primer based on phosphorimaging, no comparison between different primers is intended.

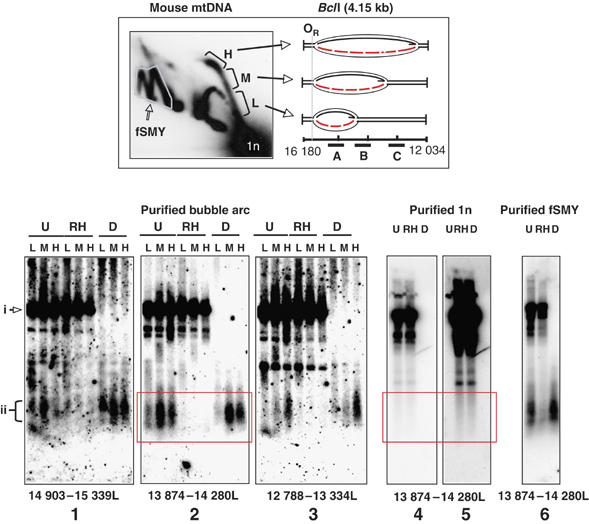

Mitochondrial initiation arcs contain continuous tracts of L-strand RNA

The above analysis of mtDNA RIs indicated the presence of extensive RNA tracts, covering in some cases the entire lagging strand, in molecules that have initiated replication within the NCR. To define in more detail the distribution of the incorporated ribonucleotides, BclI-digested mouse liver mtDNA was fractionated by preparative 2D-AGE. The prominent initiation arc associated with the NCR-containing restriction fragment was excised in three portions (see 2D gel inset in Figure 7), representing molecules in which the replication fork has advanced successively further away from the NCR. Nucleic acids were recovered from these fractions by electro-elution, heat-denatured either with or without prior nuclease treatment, and analyzed on one-dimensional agarose gels. Southern blotting and hybridization with three non-overlapping L-strand-specific riboprobes revealed fragments of 200–600 nt in size, which were sensitive to RNase H treatment prior to heat denaturation, but insensitive to DNase (Figure 7(1–3)), indicating that they consist of pure RNA hybridized to DNA. Therefore, the lagging strand initially comprises continuous RNA laid down in tracts of at least 200–600 nt.

Figure 7.

L-strand RNA derived from the initiation arc of BclI-digested mouse liver mtDNA. BclI-digested mtDNA was fractionated by 2D-AGE and low (L), middle (M) and high (H) portions of the initiation arc, as well as the fSMY arcs and non-replicating species (1n), associated with the fragment spanning nt 12 034–16 180 were excised (see inset). Nucleic acid was electro-eluted, treated with RNase H (RH), DNase (D) or left untreated (U), heat denatured, and separated on a 1.0% agarose gel. After transfer to nylon membrane, the samples were hybridized sequentially to riboprobes 13 874–14 280 (panel 2), 12 788–13 334 (panel 3) and 14 903–15 339 (panel 1), which specifically detect L-strand nucleic acid (see Materials and methods). In each case, the preceding probe was stripped from the membrane before applying a fresh probe and stripping verified by elimination of the signal. The most prominent band (i) is inferred to be template L-strand mtDNA spanning the entire fragment (nt 12 034–16 180). As expected, these molecules are RNase H-resistant but DNase-sensitive. Shorter fragments (ii) were also evident in all three fractions (L, M and H), which were, in contrast to the other species', DNase-resistant but RNase H-sensitive. The sizes of the RNase H-sensitive fragments were estimated at ∼200–600 nt based on comparison with an RNA ladder (Novagen) run in parallel (not shown). No RNA was detectable when riboprobes detecting the H-strand were tested (not shown) or unit length fragments of mtDNA (purified 1n) were analyzed (panel 4, short exposure and panel 5, long exposure). DNase-resistant, RNase H-sensitive fragments were associated with slow-moving arcs (panel 6). Thus, the pieces of RNA are exclusively L-strand and derive from bona fide replication intermediates. DNase sensitive fragments shorter than 1n were associated with both replicating (panels 1–3 and 6) and non-replicating (panels 4 and 5), fragments of mtDNA. Such fragments are presumed to relate to fragile sites in non-replicating mtDNA. A red box highlights the region of the gel where RNase H-sensitive, DNase resistant fragments were present in RIs (panel 2) and absent from non-replicating mtDNA (panels 4 and 5). (For colour figure see online.)

Discussion

The data presented here demonstrate two classes of RI in mitochondria of higher vertebrates. The two types of RI differ most markedly in ribonucleotide-content, but also in initiation zone. Those with few ribonucleotides are compatible with products of conventional, strand-coupled DNA synthesis, initiating from sites dispersed across a broad zone of many kilobases, as inferred previously (Bowmaker et al, 2003; Reyes et al, 2005). The second class of RI initiates exclusively within the NCR, and incorporate RNA on the lagging strand across virtually the entire genome. For convenience, we term the latter RITOLS intermediates (ribonucleotide incorporation throughout the lagging strand). In chick or rodent liver, RITOLS intermediates are the predominant class, and this also appears to be the case in cultured human cells and human placenta (Holt et al, 2000; Yasukawa et al, 2005 and unpublished data). RITOLS and conventional, strand-coupled RIs appear to derive from distinct types of initiation events, which suggests multiple modes of mtDNA replication operate in vertebrate tissues.

Origin(s) of RITOLS replication

Initiation of RITOLS replication is confined to the NCR based on the detection of clubheaded, RNase H-sensitive bubble arcs uniquely in NCR-containing restriction fragments, and mapping of fSMY arcs. Many initiation events must occur very close to OH, at least in mouse, since a restriction site as close to OH as 79 nt was often blocked, creating fSMY arcs (Figure 4(13)). Such replication may be considered effectively unidirectional. The weaker RNase H-sensitive initiation arcs seen in fragments containing some of the NCR without OH suggest at least one other site in the NCR serves as an origin. This other origin or origins must also be effectively unidirectional, otherwise it would produce a truncated bubble arc, or one of only minor intensity (Figure 5(17–19)). LM-PCR detected prominent H-strand 5′ ends around nt 15 625 in mouse liver (or nt 62 in chick), which are positioned approximately in the same region as a cluster of 5′ ends previously mapped in human mtDNA in cells recovering from mtDNA depletion, where they were assumed to represent a bidirectional origin (Yasukawa et al, 2005).

RITOLS represents a novel mode of DNA replication. However, it shares some features with the strand-asynchronous model. Both models predict a considerable delay between leading and lagging-strand DNA synthesis. The loss of ribonucleotide segments from RITOLS intermediates would generate molecular species corresponding to the partially single-stranded mtDNA molecules detected by EM (Robberson et al, 1972; Kasamatsu and Vinograd, 1973) and AFM (Brown et al, 2005), that is, very similar to those predicted from the strand-asynchronous model.

Some strand-separation of RIs frequently occurs during 2D-AGE if psoralen crosslinking is not employed (Pohlhaus and Kreuzer, 2006), and this is more prevalent in the case of partially single-stranded RIs, giving rise to an arc of single stranded DNA (Yang et al, 2002). Thus, while there might in theory be an additional population of mtRIs that are partially single-stranded (and lacking L-strand RNA), these would have been evident on 2D-AGE as a single-strand arc. In practice, single-stranded arcs of mtDNA were weak or undetectable in our highly purified preparations of mtDNA, unless treated with RNase H (e.g. Supplementary Figure 1; Yang et al, 2002 and unpublished data). Therefore, we feel confident in asserting that any branch migration during extraction did not materially affect the results and interpretations.

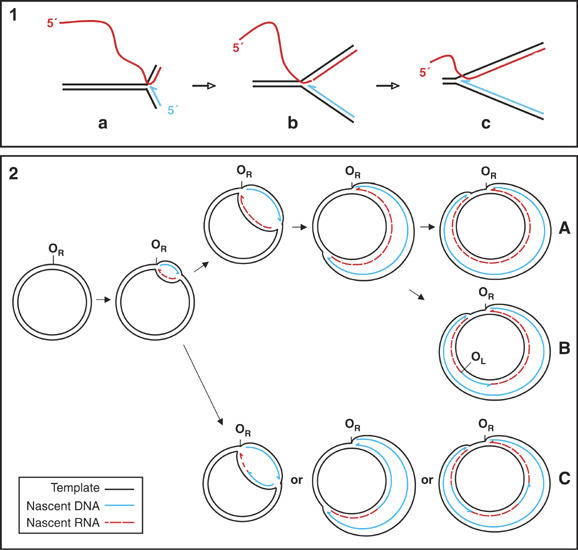

Synthesis of the nascent RNA strand

The defining feature of RITOLS is the incorporation of RNA throughout the lagging strand. This raises the issue of what molecular machinery gives rise to the nascent RNA strand. It may be created by a novel primase. Primer length is known to vary considerably in other systems. For example, in wheat nuclear DNA replication, primer length is influenced heavily by the abundance/availability of DNA polymerases, with primers up to 500 ribonucleotides observed in the absence of DNA polymerase (Laquel et al, 1994). A primase activity associated with mammalian mitochondrial extracts was reported 20 years ago (Ledwith et al, 1986; Wong and Clayton, 1986), although its properties were not investigated in detail. Alternatively, lagging strand RNA fragments might be laid down via hybridization of a displaced parental strand to nascent RNA (Figure 8(1)). In this ‘bootlace model', preformed transcript would be threaded through the advancing DNA polymerase complex, hybridizing with the displaced H-strand in the 3′–5′ direction, until the transcriptional start, or an upstream RNA processing site, is encountered. This model is consistent with the abundant RNA ‘bushes' previously found associated with mtDNA purified on cesium chloride gradients (Carre and Attardi, 1978).

Figure 8.

A model of RITOLS replication of mtDNA. RNA incorporation throughout the lagging strand (RITOLS) may be attributed either to synthesis by a primase (see Discussion) or (panel 1) to the incorporation of preformed RNA (the bootlace model). As the fork advances (from diagram a to b to c), preformed RNA is threaded through the replication complex in the 3′–5′ direction, hybridized with the displaced parental strand. Panel 2: replication initiates in an effectively unidirectional manner at a discrete origin OR (located either at OH or in the distal portion of the NCR). The lagging strand is laid down initially as RNA (red). In some molecules, the entire lagging strand is incorporated as RNA before conversion to DNA commences (A). Other molecules initiate maturation approximately two-thirds of the way around the genome (B), or at dispersed sites (C). In chicken liver mtDNA, maturation is a mixture of A and C, whereas maturation of mouse liver mtDNA occurs predominantly in the vicinity of OL (scheme B). Such a model can generate the arcs of RIs detected in the experiments presented in this paper.

Maturation of the nascent RNA strand

Although a minority of RIs appears to have a complete RNA lagging strand, others appear to be a patchwork of DNA and RNA segments. The simplest explanation is that the lagging strand is initially laid down as RNA and subsequently replaced by DNA in maturation steps. Sites in replicating mouse and chick mtDNA close to the origin gave rise to much more prominent eyebrow arcs than distant sites (Figure 1). The relative strength of eyebrow signal should depend on the time interval between incorporation of RNA and its subsequent replacement by DNA, as well as the rate of fork progression. If maturation of the RNA lagging strand takes place in the 5′–3′ direction only after leading strand DNA synthesis is complete, then the final part of the RNA lagging strand (i.e. just before the terminus back at OH) will be the first to be replaced by DNA, and sites at such positions will be blocked only transiently. Conversely, lagging strand RNA adjacent to a unidirectional origin would be the last to be replaced. This model (Figure 8(2A)) fits much of the data from chick and mouse. However, in mouse liver a distinct discontinuity in RNA content was observed near to nt 5200 (Figure 4(9)). This corresponds approximately with the site previously designated as OL, and with the occurrence of prominent L-strand 5′ ends of DNA in this region (Tapper and Clayton, 1982; Kang et al, 1997). We propose that the OL region represents a prominent site of maturation initiation (Figure 8(2B)). The absence of such a marked boundary in chick is consistent with the chick mitochondrial genome lacking an obvious equivalent of the ‘OL' spacer region in the WANCY tRNA cluster, and consistent with maturation from dispersed sites (Figure 8(2C)).

Careful inspection of slow-moving arcs migrating entirely above the linear arc (fSMY arcs) suggests an additional site of preferred maturation initiation in mouse liver, between nt 12 966 and 12 671 (Figure 4(11 and 15) and Supplementary Figure 4(20–22)). Although repeated switching during replication between RITOLS and conventional strand-coupled synthesis cannot be ruled out, the concept of alternate start sites for maturation seems simpler.

A good candidate for involvement in lagging-strand maturation is the mitochondrial isoform of RNase H1. The enzyme is essential for mammalian mtDNA maintenance (Cerritelli et al, 2003), and has recently been shown to be processive (Gaidamakov et al, 2005), unlike Escherichia coli RNase H. In nuclear DNA, RNase H1 is believed to act on long stretches of RNA: DNA hybrid formed during immunoglobulin class switching (Yu et al, 2003); the enzyme may therefore play similar roles in both compartments. Moreover, rapid processing of L-strand RNA in mitochondrial RIs, by RNase H1 or another, similar enzyme, would yield multiple short RNAs, each with the potential to prime DNA synthesis. DNA synthesis from such short RNAs could give rise to RIs essentially indistinguishable from those of conventional strand-coupled replication. Thus, an alteration in the kinetics of lagging-strand (RNA) processing may explain the dramatic switch from RNase H-sensitive to RNase H-resistant mtRIs seen in cells recovering from drug-induced mtDNA depletion (Yasukawa et al, 2005).

The physiological significance of RITOLS

The incorporation of RNA as a transient lagging-strand offers a potential means of stabilizing the displaced DNA strand and protecting it against damage during replication. Without such protection, information on the displaced strand is vulnerable to eradication, prior to synthesis of the definitive lagging strand. Whereas single-strand binding protein might afford some limited protection, RNA crucially provides also an informational back-up, and mtDNA polymerase γ has reverse transcriptase activity (Murakami et al, 2003).

The incorporation of extensive tracts of RNA during replication may additionally serve to regulate the related processes of DNA replication and transcription. Transcription takes place far more frequently than DNA replication, and in many instances traverses the entire circular genome. This means that it is highly likely that in every replication cycle the advancing replication fork will encounter successive transcription complexes travelling in the opposing direction. The creation of a provisional, RNA lagging-strand may serve as a roadblock to arriving transcription complexes, as seen for example in transcription by phage T3 RNA polymerase (Bentin et al, 2005). This would have the effect of arresting transcription until DNA replication is complete, further minimizing the potential for mutation or genome rearrangement.

Materials and methods

Purification of mtDNA

Mitochondria and mitochondrial nucleic acid of chick and rodent (mouse and rat) liver were isolated by sucrose step-gradient centrifugation, followed by proteinase K digestion and phenol–chloroform extraction as previously (Yang et al, 2002; Reyes et al, 2005).

DNA modification, separation and hybridization

Restriction enzyme digestions (New England Biolabs) and nuclease treatments (Promega) were performed on 3 μg lots of purified mitochondrial nucleic acid, under conditions recommended by the manufacturer. Unless otherwise stated, RNase H treatment was 1 U of enzyme for 30 min at 37°C; S1 nuclease treatment was 1 U for 60 s; neutral 2D-AGE was performed by the standard method (Brewer and Fangman, 1987; Friedman and Brewer, 1995) for fragments of 3–5 kb. Fragments larger than 5 kb were separated in the first dimension at 0.7–0.9 V/cm for 20–24 h on slab gels of between 0.28 and 0.35% (w/v) agarose, at room temperature. Second dimension electrophoresis was for 27–72 h at 36–100 V in gels of 0.58–0.875% agarose, at 4°C or 25°C (Krysan and Calos, 1991). Southern blots of 2D gels were hybridized to radiolabeled probes for specific regions of vertebrate mtDNA by overnight incubation at 65°C in 7% SDS, 0.25 M sodium phosphate pH 7.2. Posthybridization washes were 1 × SSC twice, 1 × SSC, 0.1% SDS twice, each for 20 min at 65°C. Filters were exposed to X-ray film and developed after 0.5–10 days.

Radiolabeled DNA probes were generated from fragments of mtDNA PCR-amplified using pairs of oligonucleotide primers (Sigma-Genosys), as follows (5′–3′).

Chick mtDNA. From (Desjardins and Morais, 1990)

probe c1 TCAGCAACCCCTGCCTGTAATG and

GGTGGAAGAACCATAACCAAATGC nt 429–826;

probe c2 CCCCATCCAACATCTCTGCTTG and

ACAAAGGCGGTGGC-TATGAGTG nt 14 963–15 260;

probe c3 GGCAACCTCGCTCTAATAGGAAC and

CAGCAGTTTTTGTGATGGTGGG nt 14 196–14 517;

probe c4 AGCAATCCGT-TGGTCTTAGGAAC and

GCGATGAGGAAGGTGAGTAGGTAG nt 13 016–13 430;

probe c5 ATCATACTCTTGCCCACAGCCC and

GCTAAGTCGTTCTGG-TTGGTTTCC nt 11 510–11 894;

probe c6 CCAACAGGAGTCAAACCCCTAAC and

AGTATCAGGCTGCTGCTTCAAATC nt 10 274–10 623;

probe c7 CAGGAGTGTTTTACGGACAATGC and

TTCAGGGGGTGGGTTTAGTTG nt 8893–9212;

probe c8 GCCTAACGCTTCAACACTCAGC and

AAGGGGGGTAA-ACTGTCCATCCTG nt 6613–7018;

probe c9 CCGAGCGATTGAAGCCACTATC and

CCTAAATGGGAGATGGATGAGAAGG nt 5390–5779;

probe c10 AAAAGAACACAACCTCCTCCAGC and

GCAGGCATCACCTTCAATACTTG nt 2842–3231;

probe c11 CAGGGTTGGTAAATCTTGTGCC and

CGTTTGTGCTC-GTAGTTCTCAGG nt 1523–1819.

Mouse mtDNA

From (Bayona-Bafaluy et al, 2003)

probe m1 CTAGGAGGTGTCCTAGCCTTAATC and

CGATAACGCATTTGATGGCCCTG, nt 15 007–15 805;

probe m2 CACAACCAACATCCCCCCTA and

GCTGTGGCTA-TGACTGCGAA, nt 13 874–14 525;

probe m3 ACATGGCCTCACATCATCACTCC and

TTATGGTGACTCAGTGCCAGGTTG, nt 11 121–11 956;

probe m4 ACGCCTAATCAACAACCGTCTCC and

CATGGACTTGGATTAACTATGT-GATATGC, nt 8031–8625;

probe m5 CACCTTCGAATTTGCAATTCG and

CTGTTCATCCTGTTCCTGCT, nt 5215–5709;

probe m6 AACAAAATACTTCGTCACACAAGCAACAGC and

GAAGGCCTCCTAGGGATAGTAATATCA, nt 4081–4676;

probe m7 CCCGTCACCCTCCTCAAATTAAATTAAAC and

GCTGTCCCTCTTTTGGCTATAATCTAAACT, nt 909–1542;

probe m8 CAAAGGTTTGGTCCTGGCCT and

TGTAGCCCATTTCTTCCCA, nt 69–790.

Labeling used 50 μCi of [α-32P]dCTP (3000 Ci/mmol, GE Healthcare), 50 ng of heat denatured DNA and DNA labeling beads (GE Healthcare), incubated for 30 min at 37°C.

LM-PCR

Standard LM-PCR was performed as described previously (Mueller and Wold, 1989; Kang et al, 1997), using the unidirectional linker of Kang et al (1997). Specific mtDNA primers were based on the current reference sequences of mouse and chick mtDNA, respectively (Desjardins and Morais, 1990; Bayona-Bafaluy et al, 2003). For detection of H-strand 5′ ends near OH, primer H1 was used for first strand synthesis, followed by ligation to the unidirectional linker, after which PCR amplification was performed with primer H2. The final two PCR cycles used primer H3, labeled with 32P using polynucleotide kinase to give radioactive fragments detectable by phosphorimaging or autoradiography. Similarly, H-strand primers for the portion of the NCR adjacent to the cytochrome b gene, cluster II, were H4, H5, and labeled H6. L-strand primers for Cluster II were L1 and L2 with labeled L3 or L4. Sequencing ladders were prepared using Promega's fmol DNA cycle sequencing system. LM-PCR and sequencing products were separated on 6% polyacrylamide gels containing 7 M urea at 36 W for 3–5 h. Nucleotide coordinates of the primers used for mtDNA of mouse (m) and chick (c) were mH1/mH4, 15 051–15 072; mH2/mH5, 15 072–15 098; mH3, 15 939–15 967; mH6, 15 353–15 377; mL1, 15 908–15 884; mL2, 15 885–15 860; mL3, 15 620–15 593; and mL4, 15 727–15 702; and cH1, 16 720–16 739; cH2, 16 739–16 758; cH3 728–747; cH4 16 469–16 488; cH5 16 479–16 500; cH6 16 662–16 186; cL1, 737–756; cL2, 718–737, and cL3, 372–391.

Initiation and fSMY arc isolation and analysis

BclI-digested mouse liver mtDNA was separated by 2D-AGE as described above. The position of the initiation arc of the OH-containing fragment (12 034–16 180) was estimated by alignment with a relevant autoradiograph, and excised under long-wave UV light, taking care to avoid contamination with the unit length fragment (1n). The initiation arc was divided into three parts: low (L), middle (M) and high (H), as illustrated in Figure 7, and nucleic acid was recovered by electro-elution into sealed dialysis tubing (3 V/cm in 1 × TBE buffer at 4°C for 5 h (L), 6 h (M) and 7 h (H). The eluate was ethanol precipitated and dissolved in 10 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.2. fSMY arcs and 1n, unit length fragments (see Figure 7, inset) were isolated by the same procedure. mtDNA, gel-extracted after 2D-AGE, was separated by 1D-AGE directly or after heating to 90°C for 90 s in 25 mM EDTA (pH 8.0). Some samples were pretreated with 1 U of RNase H (Promega) or 1 U of RQ DNase (Promega) at 37°C for 30 min. Samples were electrophoresed at 4 V/cm for 2–2.5 h, in a 1% agarose gel, after which the gel was washed twice with 10 × SSC for 10 min and capillary blotted to nylon membrane. Hybridization to riboprobes (see below) was carried out overnight in 7% SDS, 0.25 M sodium phosphate (pH 7.2), 1 mM EDTA, at 59°C. Posthybridization washes were 2 × SSC twice, 2 × SSC, 0.1% SDS twice, each for 15 min at 62°C, followed by a final wash with 0.1 × SSC, 0.5% SDS, 10 mM EDTA for 15 min at 60°C. Hybridization signals were detected with a Typhoon phosphorimager (GE Healthcare). Riboprobes were generated from amplified mouse mtDNA containing a T7 promoter, using 32P-CTP (GE Healthcare) and an in vitro transcription kit (Ambion). Riboprobes A, B and C corresponded, respectively, to nt 15 339–14 903, 14 280–13 874 and 13 334–12 788 of mouse mtDNA (Bayona-Bafaluy et al, 2003).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1.1–1.3

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to anonymous reviewers who suggested a number of modifications and clarifications to improve the manuscript. TY was the recipient of a Postdoctoral Fellowship for Research Abroad (April 2003–April 2005) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and is currently funded by the UK Muscular Dystrophy Campaign. Financial support was provided by the UK Medical Research Council, the European Union (EUMITOCOMBAT project), the Academy of Finland, Juselius Foundation and Tampere University Hospital Medical Research Fund.

References

- Arnberg A, van Bruggen EF, Borst P (1971) The presence of DNA molecules with a displacement loop in standard mitochondrial DNA preparations. Biochim Biophys Acta 246: 353–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayona-Bafaluy MP, Acin-Perez R, Mullikin JC, Park JS, Moreno-Loshuertos R, Hu P, Perez-Martos A, Fernandez-Silva P, Bai Y, Enriquez JA (2003) Revisiting the mouse mitochondrial DNA sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 31: 5349–5355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belanger KG, Mirzayan C, Kreuzer HE, Alberts BM, Kreuzer KN (1996) Two-dimensional gel analysis of rolling circle replication in the presence and absence of bacteriophage T4 primase. Nucleic Acids Res 24: 2166–2175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentin T, Cherny D, Larsen HJ, Nielsen PE (2005) Transcription arrest caused by long nascent RNA chains. Biochim Biophys Acta 1727: 97–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowmaker M, Yang MY, Yasukawa T, Reyes A, Jacobs HT, Huberman JA, Holt IJ (2003) Mammalian mitochondrial DNA replicates bidirectionally from an initiation zone. J Biol Chem 278: 50961–50969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer BJ, Fangman WL (1987) The localization of replication origins on ARS plasmids in S. cerevisiae. Cell 51: 463–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer BJ, Sena EP, Fangman WL (1988) Analysis of replication intermediates by two-dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis. In Kelly T, Stillman B (eds). Cancer Cells 6/Eukaryotic DNA Replication, pp. 229–234. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: CSH Press [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Cecconi C, Tkachuk AN, Bustamante C, Clayton DA (2005) Replication of mitochondrial DNA occurs by strand displacement with alternative light-strand origins, not via a strand-coupled mechanism. Genes Dev 19: 2466–2476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carre D, Attardi G (1978) Biochemical and electron microscopic characterization of DNA–RNA complexes from HeLa cell mitochondria. Biochemistry 17: 3263–3273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerritelli SM, Frolova EG, Feng C, Grinberg A, Love PE, Crouch RJ (2003) Failure to produce mitochondrial DNA results in embryonic lethality in Rnaseh1 null mice. Mol Cell 11: 807–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews S, Ojala D, Posakony J, Nishiguchi J, Attardi G (1979) Nucleotide sequence of a region of human mitochondrial DNA containing the precisely identified origin of replication. Nature 277: 192–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins P, Morais R (1990) Sequence and gene organization of the chicken mitochondrial genome. A novel gene order in higher vertebrates. J Mol Biol 212: 599–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman KL, Brewer BJ (1995) Analysis of replication intermediates by two-dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis. Methods Enzymol 262: 613–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaidamakov SA, Gorshkova II, Schuck P, Steinbach PJ, Yamada H, Crouch RJ, Cerritelli SM (2005) Eukaryotic RNases H1 act processively by interactions through the duplex RNA-binding domain. Nucleic Acids Res 33: 2166–2175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt IJ, Lorimer HE, Jacobs HT (2000) Coupled leading- and lagging-strand synthesis of mammalian mitochondrial DNA. Cell 100: 515–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalejta RF, Hamlin JL (1996) Composite patterns in neutral/neutral two-dimensional gels demonstrate inefficient replication origin usage. Mol Cell Biol 16: 4915–4922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang D, Miyako K, Kai Y, Irie T, Takeshige K (1997) In vivo determination of replication origins of human mitochondrial DNA by ligation-mediated polymerase chain reaction. J Biol Chem 272: 15275–15279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasamatsu H, Robberson DL, Vinograd J (1971) A novel closed-circular mitochondrial DNA with properties of a replicating intermediate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 68: 2252–2257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasamatsu H, Vinograd J (1973) Unidirectionality of replication in mouse mitochondrial DNA. Nat New Biol 241: 103–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg A, Baker TA (1992) DNA Replication, 2nd edn. New York: W.H. Freeman & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Krysan PJ, Calos MP (1991) Replication initiates at multiple locations on an autonomously replicating plasmid in human cells. Mol Cell Biol 11: 1464–1472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laquel P, Litvak S, Castroviejo M (1994) Wheat DNA primase (RNA primer synthesis in vitro, structural studies by photochemical cross-linking, and modulation of primase activity by DNA polymerases). Plant Physiol 105: 69–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledwith BJ, Manam S, Van Tuyle GC (1986) Characterization of a DNA primase from rat liver mitochondria. J Biol Chem 261: 6571–6577 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas I, Germe T, Chevrier-Miller M, Hyrien O (2001) Topoisomerase II can unlink replicating DNA by precatenane removal. EMBO J 20: 6509–6519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Parras L, Hernandez P, Martinez-Robles ML, Schvartzman JB (1992) Initiation of DNA replication in ColE1 plasmids containing multiple potential origins of replication. J Biol Chem 267: 22496–22505 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Parras L, Lucas I, Martinez-Robles ML, Hernandez P, Krimer DB, Hyrien O, Schvartzman JB (1998) Topological complexity of different populations of pBR322 as visualized by two-dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis. Nucleic Acids Res 26: 3424–3432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller PR, Wold B (1989) In vivo footprinting of a muscle specific enhancer by ligation mediated PCR. Science 246: 780–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami E, Feng JY, Lee H, Hanes J, Johnson KA, Anderson KS (2003) Characterization of novel reverse transcriptase and other RNA-associated catalytic activities by human DNA polymerase gamma: importance in mitochondrial DNA replication. J Biol Chem 278: 36403–36409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohlhaus JR, Kreuzer KN (2006) Formation and processing of stalled replication forks—utility of two-dimensional agarose gels. Methods Enzymol 409: 477–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preiser PR, Wilson RJ, Moore PW, McCready S, Hajibagheri MA, Blight KJ, Strath M, Williamson DH (1996) Recombination associated with replication of malarial mitochondrial DNA. EMBO J 15: 684–693 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes A, Yang MY, Bowmaker M, Holt IJ (2005) Bidirectional replication initiates at sites throughout the mitochondrial genome of birds. J Biol Chem 280: 3242–3250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robberson DL, Kasamatsu H, Vinograd J (1972) Replication of mitochondrial DNA. Circular replicative intermediates in mouse L cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 69: 737–741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schvartzman JB, Martinez-Robles ML, Hernandez P (1993) The migration behaviour of DNA replicative intermediates containing an internal bubble analyzed by two-dimensional agarose gel electrophoresis. Nucleic Acids Res 21: 5474–5479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapper DP, Clayton DA (1982) Precise nucleotide location of the 5′ ends of RNA-primed nascent light strands of mouse mitochondrial DNA. J Mol Biol 162: 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson JD, Crick FH (1953) Molecular structure of nucleic acids; a structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature 171: 737–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong TW, Clayton DA (1986) DNA primase of human mitochondria is associated with structural RNA that is essential for enzymatic activity. Cell 45: 817–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang MY, Bowmaker M, Reyes A, Vergani L, Angeli P, Gringeri E, Jacobs HT, Holt IJ (2002) Biased incorporation of ribonucleotides on the mitochondrial L-strand accounts for apparent strand-asymmetric DNA replication. Cell 111: 495–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasukawa T, Yang MY, Jacobs HT, Holt IJ (2005) A bidirectional origin of replication maps to the major noncoding region of human mitochondrial DNA. Mol Cell 18: 651–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K, Chedin F, Hsieh CL, Wilson TE, Lieber MR (2003) R-loops at immunoglobulin class switch regions in the chromosomes of stimulated B cells. Nat Immunol 4: 442–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1.1–1.3