Abstract

The Golden Rule guides people to choose for others what they would choose for themselves. The Golden Rule is often described as ‘putting yourself in someone else's shoes’, or ‘Do unto others as you would have them do unto you’(Baumrin 2004). The viewpoint held in the Golden Rule is noted in all the major world religions and cultures, suggesting that this may be an important moral truth (Cunningham 1998). The Golden Rule underlies acts of kindness, caring, and altruism that go above and beyond “business as usual” or “usual care” (Huang, 2005). As such, this heuristic or ‘rule of thumb’ has universal appeal and helps guide our behaviors toward the welfare of others. So why question the Golden Rule? Unless used mindfully, any heuristic can be overly-simplistic and lead to unintended, negative consequences.

A heuristic is a rule of thumb that people use to simplify potentially overwhelming or complex events. These rules of thumb are largely unconscious, and occur irrespective of training and educational level (Gilovich, Griffin & Kahneman 2002). Rules of thumb, such as the Golden Rule, allow a person to reduce a complex situation to something manageable—e.g., ‘when in doubt, do what I would want done’. Because it is a simplifying tool, however, the Golden Rule may lead to inappropriate actions because important factors may be overlooked.

In this article we describe “The Golden Rule” as used by administrators, supervisors, charge nurses, and CNAs in case studies of four nursing homes. By describing use of this rule-of-thumb, we aim to challenge nurses in nursing homes to: 1) be mindful of their use of “The Golden Rule” and its impact on staff and residents; and 2) help staff members think through how and why “The Golden Rule” may impact their relationships with staff and residents.

Introduction to the Research Study

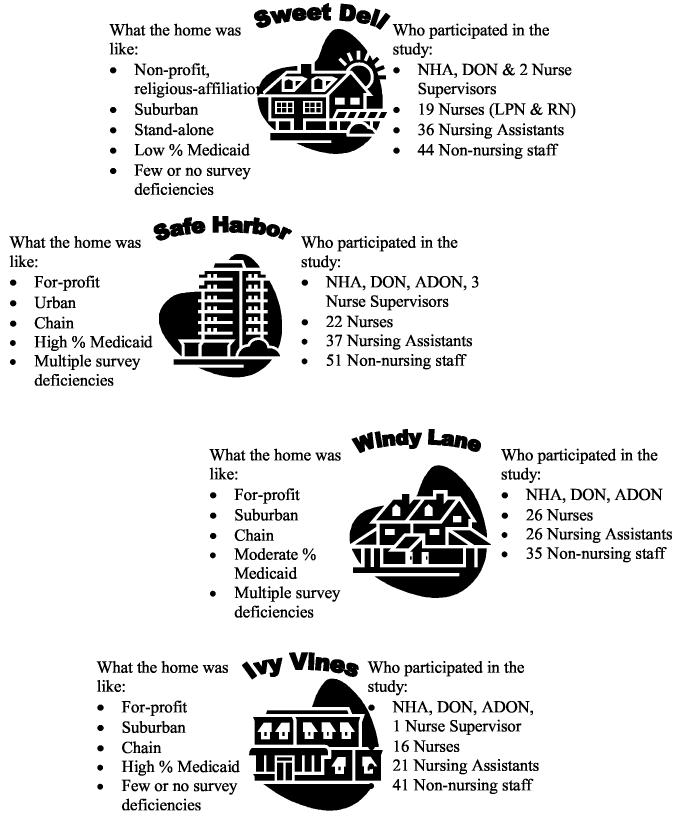

The findings presented here are drawn from four case studies about relationship patterns and nursing management practices in nursing homes in central North Carolina. Spending about six months in each nursing home, two field researchers observed staff in meetings and as they engaged in work routines, conducted in-depth interviews with staff, and collected facility documents. Figure 1 summarizes the case study nursing homes and the numbers and types of staff that participated. We transcribed all field notes, taped interviews, and documents into computerized files for analysis. Research team members read and coded the 500-plus documents comprising the data. For more details of the qualitative, comparative, case study research design, see Anderson, Crabtree, Steele and McDaniel (2005).

Figure 1.

Description of the Nursing homes (Please note: all facility names have been changed to protect the privacy of the staff and residents).

Findings

Use of the Golden Rule was prevalent in all four nursing homes, across all levels of staff and across both nursing and non-nursing departments. Below we present findings that describe the Golden Rule as used in providing direct care and as used when managing staff.

Direct Care by “The Golden Rule”. We found multiple references in the data about how “The Golden Rule” guides people in resident care. Direct care staff described the Golden Rule as helping them to see the resident as a person (i.e., this could be my grandfather or some other family member) and this appeared particularly important when a resident was difficult to work with due to cognitive impairment or behavioral symptoms. In this sense, use of the Golden Rule can be beneficial to promote resident dignity and to avoid depersonalization, or production-line, “bed and body” care. This quotation embodies this notion:

RN: [Good care is] something that I would feel comfortable with my parents or my grandparents getting.

The Golden Rule may also be an important factor in reducing the risk of neglect or mistreatment of residents. For example, a Food Service Director talks about the importance of simple acts that reflect a “Do unto others” perspective:

Some people tend to think because [residents are] old they have no feelin's, no taste buds… –[When my elderly] mother go to… dialysis and stuff, and I notice that people are not treatin' her right – and then I go call 'em on it. Around here, if I see somebody's not bein' treated right, or somebody wants somethin' …I stop and just give it to 'em. I mean, it doesn't take but a second to please 'em – one little simple gesture can make a day for a whole person.

In another example, an LPN describes her view on good resident care as consistent with her values about fundamental rights to quality care, further informed or guided by the attention one would give to family members based on kinship relationships:

I think good care is keeping residents clean…dry and intact. Keeping their quality of life as good as possible. Let them attend activities; give them their privacy… You know…respect them. Treat them as if they were your own grandmother or grandfather, mother or father, brother or sister, whatever.”

One CNA similarly describes emotional attachment that follows from use of the Golden Rule.

I treat [my residents] in a way that I would want to be treated… I have had …one [grandparent] that was in a nursing home for three years … and I know how I wanted her treated and I am not going to treat these people any different.

The Golden Rule of “Do unto others…” is conveyed by these staff to imply that the highest standard of care possible is a driving force in their day-to-day actions with residents. The following quotation from a Medical Technician also invokes emotional attachment but highlights a significant limitation of the Golden Rule in providing care.

I treat [my residents] like they are my grandma and really my friends, they are everything to me. I love them. Even if… they say, “You hurt me, ” I try to, you know be nice to them, apologize to them so they can understand that I was not trying to hurt them. I was just trying to take care of them and accidents happen.

This quotation suggests the moral imperative to provide care in a manner that goes above and beyond “usual care” as she would provide to a loved one. She is comforted by this and it helps her guard against depersonalization. Unfortunately, her comfort in using the Golden Rule may obscure the possibility that her actions cause the resident pain or harm. Her strong belief in the Golden Rule may have limited her ability to consider whether the resident needs to be touched or physically assisted in a different manner, needs better pain management of arthritis, and so forth.

In another example, nurses and family members decided in a care conference that a resident would eat her meals in her room. The CNA, unaware of the clinical reasoning behind the decision, invoked her own beliefs about social isolation and her own preferences to eat in a social setting. With the best of intentions based upon the Golden Rule, the CNA convinced the director of nursing to overturn the decision and to allow the resident to eat in the dining room. Thus, the Golden Rule may not have served the resident's best interest.

When the Golden Rule serves to associate caregiving with kinship attachment between staff and residents, care is personalized and loving based on one's own preferences or on family-related (kinship) ties. This leads to caring behaviors by staff members. However, findings show that the Golden Rule can obscure critical resident needs or preferences, despite good intentions.

Management by “The Golden Rule”: In our study, managers at all levels and across departments described the Golden Rule as a way of mentoring or teaching staff. In each case, while the Golden Rule was typically used with the intent to improve care or relationships with employees, the examples illustrate inherent limitations.

For example, a Nursing Home Administrator (NHA) challenged supervisors and mid-level managers to interpret absenteeism by CNAs more generously, using the Golden Rule.

[Supervisors] don't blink an eye at takin' half a day off to go get their child out of school, or go pick up their mother somewhere, or go for a dentist appointment… The CNA out there who wants to take a half a day off and get paid for it – [the supervisors] explode and give 'em all kinds of grief. So, you got [a double standard]. [To the supervisors] I said, ‘Would you want to be in the circumstance of these people who are workin' out there on the floor? You wanna live where they live? Have the family that they have? No. Well then respect them for what they do and how – how they survive and contribute’ … I asked them, ‘Suppose it was reversed and you had to account for all your time?’”

Here, using the Golden Rule is a powerful tool for drawing the supervisors' attention to the hardship that strict attendance policies create for direct care staff members. However, it does not address the complexities inherent in meaningfully assisting employees with attendance problems. In the following example, the Human Resources (HR) Director addresses such complexities.

I treat everybody like I want to be treated…I think I've got a really good rapport with all the employees and it works out really good that way. …If they have a problem, I try to work it out. I've placed a lot of…our…ladies in shelters for the abused…I've helped them get care for their children.

The HR Director draws upon “The Golden Rule” to go beyond her job responsibilities to facilitate problem-solving of larger life issues that impact her employees' ability to be on the job. Thus, “The Golden Rule” leads to potentially better outcomes for staff (e.g. personal safety, childcare), for the nursing home (e.g. improved attendance), and for the HR Director, herself (e.g. pride in her ability to connect with staff and advocate for them). However, the HR Director may not have the relevant professional expertise to intervene in complex psychosocial issues of staff members and she may inappropriately blur work and private boundaries. In fact, employees in one case study nursing home described feeling that managers intruded in their personal business and home life.

We observed supervisors teaching CNAs to use the Golden Rule to guide how they provide care. As we saw in the previous examples, while engendering compassion, this approach relied on the CNAs' knowledge and cultural norms to determine adequate care. Such norms may or may not match standards of nursing practices or resident preferences or values.

In this example, an Assistant Director of Nursing (ADON) uses the Golden Rule as a guideline for psycho-social care for bereaved family members. The teaching event followed a painful family experience.

[Soon after a] patient passed away, a family member overheard a CNA say, ‘Yeah, you know, when, a [resident's] dyin' the family comes out of the walls like vultures.’ Well, I just saw red [when the family member told me]. I said to the CNA, ‘How could anybody do that? Put yourself in their place. How would you feel if your mother had just died and you heard somebody say that?’

Psycho-social care is the most difficult type of care to teach to CNAs because it cannot easily be reduced to a set of care routines, as with physical care (Zinn, Brannon, Mor & Barry, 2003). In our study, we observed the ADON reducing psycho-social care to the Golden Rule. The Golden Rule, however, is a limited basis for psychosocial care following bereavement because it relies solely on empathy and it ignores the wealth of clinical knowledge available to guide CNAs in the variety of death and dying situations they will face in their work.

Discussion

The use of the Golden Rule as a simplifying tool is particularly problematic in the diverse world of long-term care. The diversity in culture, ethnicity, religion and age is vast among managers, health professionals, direct care workers and residents. As our findings suggest, while trying to put yourself in another person's shoes facilitates empathy and connection with staff or residents, it is unrealistic to assume that you could truly understand an individual's wishes, needs, interests or preferences (Bruton 2004; Huang, 2005). Fundamental differences arise from multiple factors such as ethnic background, education, professional discipline, age cohort, and disease state. Recognizing and understanding The Golden Rule as a heuristic, or rule of thumb, helps us evaluate its impact on care outcomes in a more useful way. Heuristics cannot be eliminated, nor are they inherently positive or negative (Gilovich, Griffin & Kahneman 2002); the challenge is to be mindful of when and how you use such rules-of-thumb.

Strategies for Challenging your Thinking about “The Golden Rule”: Remember that heuristics are universally employed to manage otherwise overwhelmingly complex and uncertain environments; thus, use of the “Golden Rule” is unavoidable. Fortunately, our findings suggest multiple positive outcomes of the “Golden Rule” for both the individual who employs it, as well as the recipient. Our analysis also suggests that adverse outcomes are likely because, as a heuristic, the Golden Rule reduces the number of alternatives considered in problem solving. The following strategies may help to improve outcomes with the use of “The Golden Rule.”

Be mindful of when and why you used the “The Golden Rule.” Question whether you are using “The Golden Rule” as a substitute for important clinical expertise or for a lack of critical information about a staff member or resident.

When using the Golden Rule, consider the preferences of the person who is affected. This is described as “Do unto others as they would have you do unto them” (Bruton 2004; Huang, 2005). A corollary to the Golden Rule is respecting the autonomy of care recipients, engaging in thoughtful reflection and comparison of different courses of action that could be taken, and basing your actions on the known or imagined wishes of that person.

Try paying attention the next time you use “The Golden Rule” in supervising a staff member. Ask yourself, “Was this more about making me feel better and have I considered the staff member's or resident's wishes or needs?” Feelings of well-being associated with the Golden Rule are powerful and may obscure insights about the recipient's perspective. Consider the perspectives of others and how one's actions affect them (Bruton, 2004). Use of the Golden Rule is of little practical value if you do not know the other's perspective.

Another question to ask yourself when you catch yourself using “The Golden Rule” is, “What just happened to make me use ‘The Golden Rule’?” Try to identify the underlying dilemma, such as the ADON who was frustrated by the CNA's lack of knowledge of how to handle end-of-life family issues, or the NHA who was struggling to teach his supervisors a better way to handle staff absenteeism. By identifying those knowledge gaps, you can begin to meaningfully address staffing and care issues, while preserving the positive aspects of “The Golden Rule” such as empathy, altruism, caring, and humane connection. For example, the HR Director we described could advocate for an employee assistance program to bring in the professional expertise required to address staff issues that led her to use the “Golden Rule” in ways that ultimately were viewed as intrusive by some staff.

Strategies for Learning with Staff and Supervisors: Just as the key to challenging your individual thinking about “The Golden Rule” is to practice mindful awareness, successful learning among managers and staff will require similar awareness. The following strategies may help in facilitating staff learning:

Engage staff in group brainstorming about using “The Golden Rule” with examples of both desirable and undesirable outcomes. Staff may become anxious when they begin to see the uncertainty and complexity behind its use. Therefore, rewarding staff for their appropriate use of the Golden Rule is as important as promoting discussion about alternatives to it.

Provide managers and staff to with resources for problem solving and decision making as a substitute for the “The Golden Rule.” Pay attention to staff and note frequently reoccurring problems that distract staff from care delivery. For example, transportation issues may often be problematic for CNAs, even under the best of conditions; snow days can wreak havoc. How you handle this issue may alleviate frustration and stress, or make matters worse. Invoking the Golden Rule may facilitate problem solving and maintain staffing levels.

Capitalize on the universal appeal of the Golden Rule with direct care staff by verbalizing and modeling acts that are based on this principle. For example, removing soiled clothing protectors after meals, changing and toileting incontinent residents promptly, shaving men and grooming women regularly, dressing residents in matching clothes, serving meals when the food is hot, etc., reflect acts that must be timely and consistent for good care, and may be appropriately motivated by the Golden Rule.

Conclusion

There is probably no moral principle that is more understood and used across cultures than the Golden Rule. Like all heuristics or “rules of thumb”, the “Golden Rule” helps us make sense of a complex and diverse environment to take action for the benefit of the receiver. “The Golden Rule” simplifies complicated situations by having us assume our own perspective about how we would like to be treated as the standard for how others would wish to be treated. Moreover, the positive effects of “The Golden Rule” sustain its use: it helps us connect with others, increases our tolerance for challenging staff or resident behaviors, and inspires us to ‘go the distance’.

As leaders in long-term care, nurses are challenged to be mindful of the extent to which applications of “The Golden Rule” may pose significant, potentially negative consequences for staff or residents, especially when the intended recipients' desires, preferences or wishes are unknown or not considered. Nurse leaders should engage in dialogue with other managers and staff to sharpen everyone's sense of discernment about the how the Golden Rule informs decisions that arise from common but complex clinical and management situations.

Acknowledgements

Funded by NIH/NINR (2 R01 NR003178-04A2, Anderson, PI), the Trajectories of Aging and Care Center (NINR 1 P20 NR07795-01, Clipp PI); Dr. Bailey is a John A. Hartford BAGNC Scholar; Dr. Piven was supported in part through NIA AG000-29.

References

- Anderson RA, Crabtree BF, Steele DJ, McDaniel RR. Case study research: the view from complexity science. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(5):669–685. doi: 10.1177/1049732305275208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrim SB. The shoes of the other. The Philosophical Forum. 2004;35(4):397–410. [Google Scholar]

- Bruton SV. Teaching the golden rule. Journal of Business Ethics. 2004;49(2):179–187. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham WP. The golden rule as universal ethical norm. Journal of Business Ethics. 1998;17(1):105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Gilovich T, Griffin D, Kahneman D. Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Yong. A copper rule versus the golden rule: The Daoist-Confucian proposal for global ethics. Philosophy of east and west. 2005;55(3):394–425. [Google Scholar]

- Zinn JS, Brannon D, Mor V, Barry T. A structure-technology contingency analysis of caregiving in nursing facilities. Health Care Management Review. 2003;28(4):293–306. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200310000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]