Abstract

In the formation of COPI vesicles, interactions take place between the coat protein coatomer and membrane proteins: either cargo proteins for retrieval to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) or proteins that cycle between the ER and the Golgi. While the binding sites on coatomer for ER residents have been characterized, how cycling proteins bind to the COPI coat is still not clear. In order to understand at a molecular level the mechanism of uptake of such proteins, we have investigated the binding to coatomer of p24 proteins as examples of cycling proteins as well as that of ER-resident cargos. The p24 proteins required dimerization to interact with coatomer at two independent binding sites in γ-COP. In contrast, ER-resident cargos bind to coatomer as monomers and to sites other than γ-COP. The COPI coat therefore discriminates between p24 proteins and ER-resident proteins by differential binding involving distinct subunits.

COPI vesicles mediate transport in the early secretory pathway and are involved in the retrieval of endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-resident proteins from the Golgi apparatus to the ER (23). Numerous transmembrane ER-resident proteins have conserved KKXX motifs at the extreme C termini of their cytoplasmic tails (17). As there is an ongoing flow of transport from the ER to the Golgi, ER residents may escape the organelle and thus need to be retrieved to their proper location. The KKXX motifs are recognized by the coatomer complex (4), which coats COPI vesicles (6, 38, 42). Therefore, escaped ER residents can be retrieved from the Golgi through the COPI system by direct interaction between a conserved recognition sequence and the coat protein (24). In contrast to escaped ER residents, which are vectorially transported to their proper localization, other transmembrane proteins are found in the early secretory pathway, where they constitutively cycle between the ER and the Golgi by using the COPII and the COPI systems, such as members of the p24 family of type I transmembrane proteins, e.g. (29). The p24 proteins were shown to be major components of COPI-coated vesicles (39, 41). Their cytoplasmic tails have two conserved motifs: a diphenylalanine motif and a dibasic motif. While in mammalian p25 and its yeast orthologs the dibasic motif is identical to the KKXX motif, this is not the case for all the other family members. Yeast and mammalian p25 proteins were described as depending on their KKXX sequence in order to bind to an α/β′/ɛ-COP subcomplex of coatomer, whereas yeast and mammalian p24 and yeast p26 were described as depending on their diphenylalanine motif in order to bind to a β/γ/ζ-COP subcomplex (10). Finally, yeast p23 and mammalian p26 were described as not binding to coatomer (10). However, this study is hard to interpret, since cytoplasmic tails of yeast or mammalian p24 proteins were both used with mammalian coatomer. Moreover, other studies presented contradictory results showing that p23 and p25 are the only p24 proteins that can bind to coatomer (5), while yet others described binding of p24 but not of p26 (12). Additionally, it appears that the FF motif and the dibasic motif are both important and probably cooperate to mediate binding of p24 proteins to coatomer (3, 5, 12, 39). From all these data, one can conclude that p24 proteins bind to coatomer via an FFXXBB(X)n motif, where B stands for a basic amino acid and n is ≥2. However, as all p24 proteins contain this motif, it is unclear why not all of them have been found to bind to coatomer. The presence of a conserved dibasic motif in the cytoplasmic tails of p24 proteins has led to the assumption that these constitutively cycling proteins share a common mechanism with cargo proteins containing a KKXX motif in order to bind to coatomer. The location of this common binding site was attributed to either the γ-COP or the α- and β′-COP subunits, depending on the technique used (8, 14, 15, 45). To investigate at a molecular level the mechanism of binding to coatomer of cycling proteins and ER-resident cargos, we have expressed and purified subdomains of γ-COP as well as the full-length protein. Binding to cytoplasmic tails of p24 proteins and of cargo proteins by γ-COP and its subdomains was evaluated using several assays. We find that p24 proteins require dimerization in order to bind to coatomer. This interaction involves two discrete and independent binding sites located on the trunk and on the appendage domain of γ-COP. In contrast, no binding was observed between γ-COP and the cytoplasmic tails of ER-resident proteins, which are known to bind to α- and β′-COP (8). The COPI coat therefore discriminates between p24 proteins and ER-resident proteins by differential binding involving distinct subunits.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Antipeptide antibodies to γ-COP were raised in rabbits against the internal peptide sequences MDDDNEVRDR (γ800, antitrunk) and VAATRQEIFQEQ (γ768, antiappendage) coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin as described previously (9). The antibody CM1 (31) was produced from hybridoma cells donated by James E. Rothman (Columbia University, New York, N.Y.). Anti-p23 cytoplasmic domain antibody is described in reference 39. The synthetic peptides have been described elsewhere (14, 15, 34). Coatomer was isolated as described in reference 32.

DNA constructs.

The cDNAs for the γ-COP subdomains were constructed by PCR using a cDNA encoding full-length bovine γ-COP as the template. The primers used were 5′-ATCATATGCTGAAGAAATTCGACAAGAAGGACGAG and 5′-ATGGATCCCTACTCCAGCACGTTGAGGTAGAAGG (underlining indicates the restriction site, and bold characters indicate start and stop codons) for the γ-trunk and 5′-ATCATATGCAGAAGCAGAAGGCGCTCAATGC and 5′-ATGGATCCCTAGCCCACAGACGCCAAGACG for the γ-appendage. Both PCR products were digested with the enzymes NdeI and BamHI (New England Biolabs) and subcloned into pET-15b plasmid (Novagen) by use of standard techniques. For bicistronic expression of glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged ζ-COP and γ-COP, the ζ-COP open reading frame (ORF) was first cloned into pPRO-GST-TEV (a kind gift from Ed Hurt), and then a second ribosomal binding site was created in the 5′ region of the γ-COP ORF by PCR using a primer including the ribosomal binding sequence GAAGGA in front of the γ-COP start codon. This 5′ primer sequence was 5′-GGGGGGGGATCCAATAATTTTGTTTAACTTTAAGAAGGAGATATACATATGCTGAAGAAA TTCGACAAGAAGGACGAG, with the ribosomal binding site shown in italics. The γ-COP PCR fragment containing the second ribosomal binding site was inserted downstream of the ζ-COP stop codon. For the microplate assay, fusion proteins were constructed as follows: cDNAs encoding the cytoplasmic tail of interest were inserted in the pET-32-Xa/LIC plasmid (Novagen), yielding a cDNA encoding thioredoxin fused to a His tag, followed by an S tag, followed by the cytoplasmic tail. For the dimeric fusion proteins, an additional cysteine codon was added upstream the cytoplasmic tail sequence. The list of the oligonucleotides that were used is available upon request. Plasmids encoding MBP (maltose binding protein) fused to a coiled-coil sequence mediating dimerization or tetramerization (44) and to the cytoplasmic tail of p23 were kind gifts of Blanche Schwappach. The thioredoxin, His tag, and S tag cassette from pET-32-Xa/LIC was excised with the enzymes XbaI and BglII and ligated upstream of and in frame with the MBP ORF.

Protein expression and purification.

Both γ-COP fragments were expressed as N-terminally His-tagged proteins. They were produced in Escherichia coli BL21pLysS cells (Novagen) according to supplier recommendations. Cell lysis was performed with an Emulsiflex instrument (Avestin), and lysates were centrifuged at 30,000 × g for 10 min and then at 100,000 × g for 1 h. The second supernatant was then incubated for 30 min at 4°C with Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid beads (QIAGEN) that had been preequilibrated with lysis buffer (50 mM Na2HPO4, 400 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], pH 8). The beads were then washed three times with lysis buffer containing 50 mM imidazole, and the tagged proteins were eluted with lysis buffer containing 250 mM imidazole.

To improve solubility and to ensure correct folding, full-length γ-COP was coexpressed with GST-tagged ζ-COP in BL21pLysS cells. The cells were lysed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1 mM DTT and, after centrifugation, they were incubated with 1 ml of glutathione Sepharose beads (Amersham biosciences) for 1 h at room temperature (RT). The beads were then washed three times with PBS containing 1 mM DTT, and the recombinant proteins were eluted with 20 mM Tris (pH 8), 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM glutathione, 1 mM DTT. GST and GST-ζ-COP did not show any binding in any of the binding assays used in this study.

Monomeric thioredoxin fusion proteins were expressed in BL21star cells (Invitrogen) and purified as the γ-COP fragments. After elution, the buffer was exchanged for buffer A (50 mM HEPES, 90 mM KCl, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) containing 10% (vol/vol) glycerol and 2 mM DTT with a PD-10 gel filtration column (Bio-Rad). Dimeric fusion proteins were expressed in E. coli origami2 cells (Novagen) and purified like the monomers, except that no DTT was used in the buffers. After the Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid step, the eluted protein was loaded on a Superdex 75 (Amersham biosciences) gel filtration column. Fractions eluting at the expected size of the dimeric fusion protein were pooled. The tetrameric p23 tail fusion protein was purified in the same way as the dimeric fusion protein except that a Superdex 200 column was used for the final step.

Bead pull-down assay, coatomer precipitation assay, and photo-cross-linking.

The bead pull-down assay, the coatomer precipitation assay, and photo-cross-linking were performed as described in references 13, 34, and 39.

Protein cleavage with hydroxylamine and isolation of cross-linked fragments.

The CM1 antibody was incubated with protein A-Sepharose material (Sigma), and after a washing step, it was chemically cross-linked to protein A with dimethyl pimelimidate (Sigma). Cross-linked coatomer was immunoprecipitated with the CM1 antibody to remove nonreacted biotinylated photoactive p23 peptide. The immunoprecipitated material was dissociated and eluted with 90 μl of 0.2 M Na2CO3, 8 M urea, pH 9, at 70°C. Half of the eluted material was then mixed with 45 μl of 0.15 M Na2CO3, 6 M NH2OH, pH 9, and incubated for 4 h at 45°C. Both hydroxylamine-treated and nontreated materials were then diluted to 1.5 ml with PBS containing 1% Triton X-100. They were then incubated with 10 μl of streptavidin-Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences) for 30 min at room temperature. After extensive washing with PBS containing 1% Triton X-100, the bound material was eluted with 20 μl of PBS containing 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS).

Microplate-based binding assay.

Wells of a 96-well microtiter plate (Greiner) were coated with 10 pmol of γ-appendage, γ-trunk, or γ-COP dissolved in 100 μl of PBS. To measure nonspecific binding, wells were coated with ovalbumin under the same conditions. Coating was carried out overnight at 4°C. Three hundred microliters of PBS-T (PBS with 0.05% Tween 20) containing 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) was added to each well for at least 30 min at RT to block any noncoated site. The plates were then washed twice with PBS-T and incubated with different dilutions of the fusion protein constructs in binding buffer (buffer A containing 1% BSA and 0.5% Triton X-100) for 1 h at RT. After binding, the plates were washed five times with binding buffer and subsequently incubated with 100 μl per well of a 1:4,000 dilution of S protein-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (Novagen) in binding buffer for 30 min at RT. The plates were then washed three times with binding buffer and once with binding buffer without BSA and Triton X-100. Detection was carried out by adding 100 μl of substrate solution [2,2′-azino-bid(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid); Sigma] per well and incubating until a coloration was seen in approximately five wells of the same dilution row. The reaction was stopped by adding 100 μl of a 1% SDS solution in water, and the absorbance at 405 nm was measured with a microplate reader (Anthos Labtec instruments).

To immobilize coatomer, 96-well microtiter plates precoated with protein A (Perbio Science) were used. Three hundred microliters of PBS-T containing 5% BSA was added to each well, and the plates were incubated overnight at 4°C. The plates were then washed twice with PBS-T and subsequently incubated with 100 μl per well of CM1 antibody (from a hybridoma cell supernatant) for 30 min. After being washed with binding buffer, the plates were incubated for 1 h at RT with a solution of 0.1 μM coatomer in PBS-T containing 1% BSA (100 μl per well), and the wells used to measure nonspecific binding were incubated with buffer. Thereafter, the assay proceeded as described above for the binding of the fusion proteins. For detection, a solution of tetramethylbenzidine (5 μg in 100 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide added to 50 ml of 0.1 M sodium carbonate buffer at pH 6 and containing 0.02% H2O2) was used. The coloration was stopped by adding 50 μl of a 0.5 M sulfuric acid solution and measured at 450 nm with a microplate reader.

RESULTS

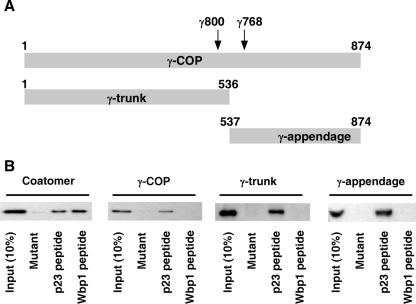

With its sequence homology to adaptin proteins (36), γ-COP is predicted to contain two subdomains: a trunk domain of about 60 kDa and an appendage domain of about 40 kDa. We have reported a stable 60 kDa γ-COP fragment after limited proteolysis (34), and the appendage-analogous domain was crystallized recently (16, 43). In order to define domain sequences for recombinant expression, we subjected coatomer to limited proteolysis. Stable γ-COP fragments with apparent sizes of around 59 kDa and 38 kDa were observed after protease treatment (not shown). These fragments were defined by their reactivity with antibodies directed against amino acid residues 518 to 527 and 605 to 616 in γ-COP, termed anti-γ-trunk and anti-γ-appendage, respectively (Fig. 1A). These results are in accordance with the predicted structure of γ-COP and are reminiscent of similar results with clathrin adaptors (22). In order to characterize both subdomains, they were expressed as recombinant proteins in E. coli as follows: γ-COP[1-536], termed the trunk domain, and γ-COP[537-874], termed the appendage domain.

FIG. 1.

γ-COP binds to p23 but not to Wbp1. (A) Schematic representation of full-length γ-COP and its recombinant trunk and appendage domains. The relative positions of the epitopes of the antibodies against trunk (γ800) and appendage (γ768) domains are indicated by the arrows. (B) Coatomer, full-length γ-COP, γ-trunk, and γ-appendage were incubated with thiopropyl-Sepharose beads coupled to a mutant peptide, p23, or Wbp1 cytoplasmic tail peptides. Input and bound material were analyzed by Western blotting with the anti γ-COP antibodies γ768 (antiappendage) for coatomer, γ-COP, and γ-appendage and γ800 (antitrunk) for γ-trunk.

Both the trunk and appendage domains bind to p23 but not to Wbp1.

In order to analyze their site of interaction within γ-COP, peptides corresponding to the C-terminal cytoplasmic tails of the cycling protein p23 and the ER-resident Wbp1 were covalently coupled to Sepharose beads and incubated with purified coatomer, full-length γ-COP, and both γ-COP subdomains. As a control, we used a mutant p23 peptide in which the FFXXBB coatomer binding motif was replaced by AAXXSS (39). As expected, purified coatomer bound to the p23 and Wbp1 beads (Fig. 1B). In contrast, full-length γ-COP and both trunk and appendage domains bound to the immobilized p23 peptide but not to the mutant or to the Wbp1-beads.

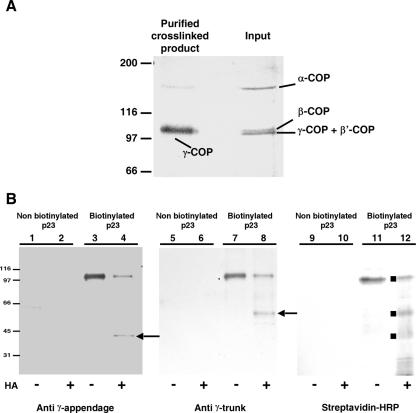

To determine if both p23 binding sites in γ-COP exist and are accessible within native coatomer as well, we used a biotinylated photoactivable p23 peptide (b-*p23) which, upon exposition to UV light, can be cross-linked to interacting partners. We previously reported that this peptide can be specifically cross-linked to γ-COP within coatomer (15). We then sought to determine if b-*p23 could be cross-linked to both trunk and appendage domains of γ-COP, as would be expected by the presence of a binding site for p23 in both subdomains. After incubation with coatomer and UV irradiation, b-*p23 could be cross-linked to a protein of about 100 kDa, as indicated by the single band observed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2, lane 11). This cross-linked product was purified through dissociation with urea and incubation with streptavidin-coupled beads. Analysis by mass spectrometry of this product unambiguously identified this band as γ-COP, as no peptide belonging to any other COP subunit could be detected (not shown). Making use of a unique cleavage site that splits γ-COP into its trunk and appendage domains, we could show that b-*p23 is indeed cross-linked to both γ-COP subdomains (Fig. 2, lanes 4, 8, and 12). In this experiment, appendage and trunk domains covalently cross-linked to the p23-peptide could be recovered in similar amounts, indicating that both binding sites are used to similar extents.

FIG. 2.

Both binding sites for p23 exist in native coatomer. (A) Left: a biotinylated photolabile p23 peptide was used to allow covalent attachment to coatomer. The cross-linked products were purified on streptavidin-coupled beads and analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with Coomassie blue staining. Right: as a comparison, immunopurified coatomer was loaded on the same gel. The labeled bands were identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization analysis. Note the striking enrichment of γ-COP in the purified cross-linked sample, indicating the specificity of the cross-link. (B) A biotinylated photolabile p23 peptide was used to allow covalent attachment to coatomer. After hydroxylamine cleavage (1) of an asparaginyl-glycine bond present in γ-COP, fragments cross-linked to p23 were purified through streptavidin-coupled beads. There is a unique Asn/Gly bond within γ-COP located at positions 549/550 connecting γ-COP's trunk and appendage domains. Lanes: 3, 7, and 11, mock-treated samples; 4, 8, and 12, hydroxylamine-treated samples; 1, 2, 5, 6, 9, and 10, samples corresponding to a control experiment, which was performed with a nonbiotinylated peptide. In these samples, no unspecific signal can be detected. In lane 12, the black squares indicate the three prominent bands that can be decorated with streptavidin-HRP and that migrate at the expected sizes for full-length γ-COP, γ-trunk, and γ-appendage. In lanes 4 and 8, arrows indicate the γ-appendage and the γ-trunk, respectively. In these two lanes, signal quantification indicates a similar ratio (of 60/40) between recovered noncleaved γ-COP and cleaved γ-COP, indicating that the photoactivable peptide was cross-linked to similar extents to both γ-COP subdomains. Numbers on the left sides of the gels indicate molecular masses.

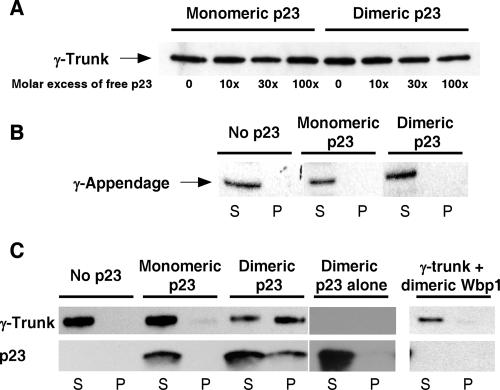

The appendage domain specifically binds to dimers of p23.

We have previously described that, in biological membranes, p24 proteins are found either as monomers or as dimers (18). We then wanted to test if the binding sites within γ-COP show any preference for monomers or dimers of p23. Such a preference would not necessarily be detectable in a classical pull-down experiment, as the coupled peptides can be densely packed on the surface of the beads and mimic oligomers. Therefore, binding to each domain was examined in pull-down experiments in which various amounts of free monomeric or dimeric peptide (Fig. 3A) in solution were used to compete with coupled p23. Appendage domain binding to the p23-coupled beads could not be abolished with an excess of free monomeric p23 peptide; however, efficient competition was observed with a dimeric p23 peptide in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3B). The binding was further analyzed by gel filtration experiments in which the appendage domain and the peptides were incubated prior to loading on a size exclusion column. The appendage domain and the dimeric p23 peptide coeluted in fractions corresponding to the apparent size of the γ-COP fragment, while the monomeric p23 peptide was not found in fractions containing the γ-appendage (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

The γ-appendage binds to dimers of p23 tails but not to monomers. (A) Structure of the peptides and fusion proteins used in this study. (B) In the binding assay described for Fig. 1, γ-appendage was preincubated with an increasing molar excess of free p23 peptide in solution in either its monomeric or its dimeric form as indicated. The material bound to the beads was analyzed by Western blotting. (C) Chromatograms of gel filtration experiments. γ-Appendage was incubated with a monomeric p23 cytoplasmic tail peptide (left) or with the dimeric form (right). The samples were loaded on a Superdex 200 gel filtration column (Amersham Biosciences), and 50-μl fractions were collected. The fractions were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against γ-appendage or p23. Void volume (Vo) and inclusion volume (Vi) are indicated. OD214, optical density at 214 nm.

The trunk domain precipitates upon binding to p23 dimers.

No competition was observed when we tried to displace the trunk domain from p23-coupled beads with free p23 peptides, either monomeric or dimeric (Fig. 4A). This behavior suggested that the trunk domain may precipitate upon binding to p23. In order to test this possibility, we incubated both γ-COP fragments with free monomeric or dimeric p23 peptides in solution and, after a centrifugation step, analyzed the contents of the soluble and insoluble fractions. The γ-appendage did not precipitate upon incubation with p23 (Fig. 4B), whereas the trunk domain precipitated upon incubation with the dimeric peptide (Fig. 4C). Note that in the precipitated material, both the γ-trunk and the dimeric peptide could be found, indicating that binding occurred and led to precipitation of the complex. This precipitation seems to be specific, since when the dimeric p23 peptide was incubated with the appendage domain, they were both found exclusively in the supernatant after centrifugation. Additionally, incubating the γ-trunk with a dimeric Wbp1 peptide (length and charge similar to that of the p23 peptide) did not lead to the precipitation of the γ-COP fragment. Altogether, the data suggest that dimers of p23, when bound to the γ-trunk, trigger a conformational change that leads to the precipitation of the complex.

FIG. 4.

The γ-trunk binds to dimers of p23 tails but not to monomers. (A) In the binding assay described for Fig. 1, γ-trunk was preincubated with an increasing molar excess of free p23 peptide in solution either in its monomeric form or in its dimeric form as indicated. The material bound to the beads was analyzed by Western blotting. (B) Five picomoles of γ-appendage was incubated for 1 h at room temperature with no peptide, 50 μM of monomeric p23 peptide, or 50 μM of dimeric p23 peptide as indicated. The samples were then centrifuged for 30 min at 100,000 × g. The pellets (P) and the supernatants (S) were analyzed by Western blotting. The lines indicate that relevant lanes were digitally isolated from the original picture. (C) The experiment was performed as for panel B, except that the γ-trunk was used. In addition, a gel system that allowed detection of the p23 peptides was used.

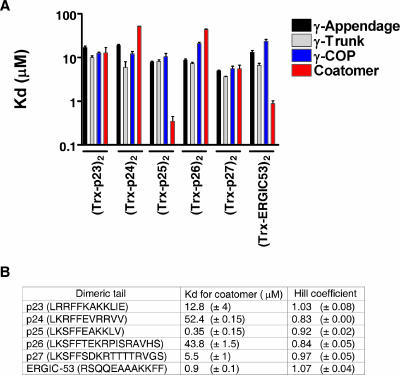

All p24 family members bind as dimers to both γ-COP binding sites.

Contradictory data exist as to which p24 proteins bind to coatomer and which do not (3, 5, 10, 12, 39). All these data are based on binding assays that used monomeric peptides coupled to beads. With this technique, the tails are not presented to coatomer in a defined oligomeric state, and the outcome of the assay may depend on the density of the peptides on the beads. Therefore, we developed a binding assay that immobilized coatomer or its subunits, rather than its putative ligands, and allowed us to use the cytoplasmic tails in a defined monomeric or dimeric state. In this assay, samples of coatomer, full-length γ-COP, or its subdomains were coated onto a 96-well microplate, and the binding of increasing amounts of dimeric fusion proteins harboring cytoplasmic tails was measured. For defined dimerization, we used fusion proteins instead of peptides, because some tail peptides have a tendency to oligomerize in a concentration-dependent manner (11, 34). The cytoplasmic tails of p24 proteins were thus fused to the C terminus of the monomeric protein thioredoxin with a linker made of an S tag and a His tag. For dimerization, a cysteine residue was added directly before the tail to allow covalent linkage of two chimeric protein chains. Dimerization readily occurred by spontaneous oxidation, and the dimeric fusion proteins could be further purified through gel filtration, where they eluted in fractions corresponding to their expected size as dimers (not shown). Binding to both fragments was saturable, and equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) values were estimated. For all of the dimeric cytoplasmic tails of p24 proteins tested, the dissociation constants for full-length γ-COP and its two subdomains were similar, in a range from about 5 μM to 15 μM (Fig. 5A). Similar p24 family fusion proteins, without an additional cysteine residue and thus monomeric, were also analyzed. For all the monomeric p24 protein tails, no binding to γ-COP or its subdomains could be detected (not shown) in the concentration range of the assay (KD ≤ 100 μM).

FIG. 5.

Analysis of the binding of dimeric tails of p24 proteins to coatomer. (A) Binding levels of dimeric fusion proteins harboring the cytoplasmic tails of p23, p24, p25, p26, p27, and ERGIC-53 were tested in the microplate assay for the γ-appendage, γ-trunk, full-length γ-COP, and complete coatomer. The KD values derived from the fits are plotted as a histogram. Error bars represent the standard errors of the mean (SEM) calculated from at least three independent experiments. (B) KD values and corresponding Hill coefficients calculated for the interactions of the indicated tails with coatomer. The standard error for each value is indicated in parentheses.

Within coatomer, trunk and appendage domains bind to p24 proteins independently.

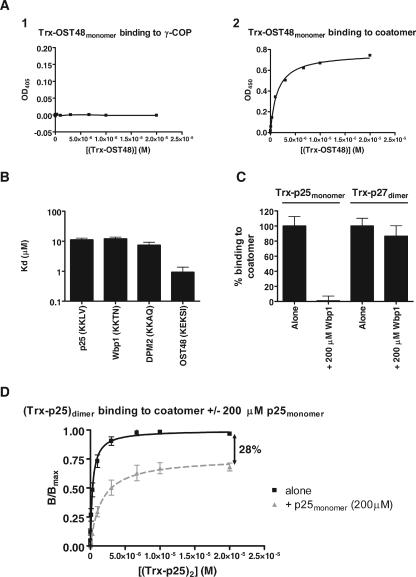

In order to investigate any cooperativity that might exist between the two γ-COP binding sites within coatomer, the complex was analyzed in the microplate assay. As summarized on Fig. 4B, native coatomer complex behaved like γ-COP for dimeric p23, p24, p26, and p27, with dissociation constants in the same order of magnitude. Interestingly, the only tail with a true KKXX sequence (p25) showed an affinity higher by a factor of 20. Cooperativity is, however, unlikely to exist in all conditions analyzed, because the Hill coefficients for these equilibria were all close to 1 (Fig. 5B). The monomeric p24 family fusion proteins did not show any detectable binding to coatomer in the assay (not shown), with the exception of monomeric p25, which showed a dissociation constant of about 10 μM (Fig. 6B). As the p25 monomer did not bind to γ-COP, this interaction must involve other subunits.

FIG. 6.

Binding of monomeric cytoplasmic tails to coatomer. (A) Samples of γ-COP (1) or coatomer (2) were analyzed in the microplate-based assay for their binding to (Trx-OST48)monomer. The corresponding data were plotted with the software PRISM (Graphpad), and when possible the data were fitted to a hyperbole. OD405, optical density at 405 nm. (B) Binding to coatomer of monomeric fusion proteins harboring the cytoplasmic tails of p25, Wbp1, DPM2, or OST48 were tested in the microplate-based assay. The KD values derived from the fits are plotted as a histogram. (C) (Trx-p25)monomer or (Trx-p27)dimer (2 μM) was incubated in wells precoated with coatomer. Where indicated, the incubation was performed in the presence of 200 μM of Wbp1 tail peptide. The resulting binding of the fusion proteins was detected with S protein conjugated to HRP. (D) The binding (B/Bmax) of (Trx-p25)dimer to coatomer in the absence (black squares) or in the presence (gray triangles) of 200 μM of p25monomer tail peptide was analyzed in the microplate-based assay. The corresponding data were normalized (the calculated saturation in the absence of competing peptide was set to 1 [Bmax]). As indicated, the plateau in the presence of the competing peptide was decreased by 28%. Error bars represent the SEM calculated from at least three independent experiments.

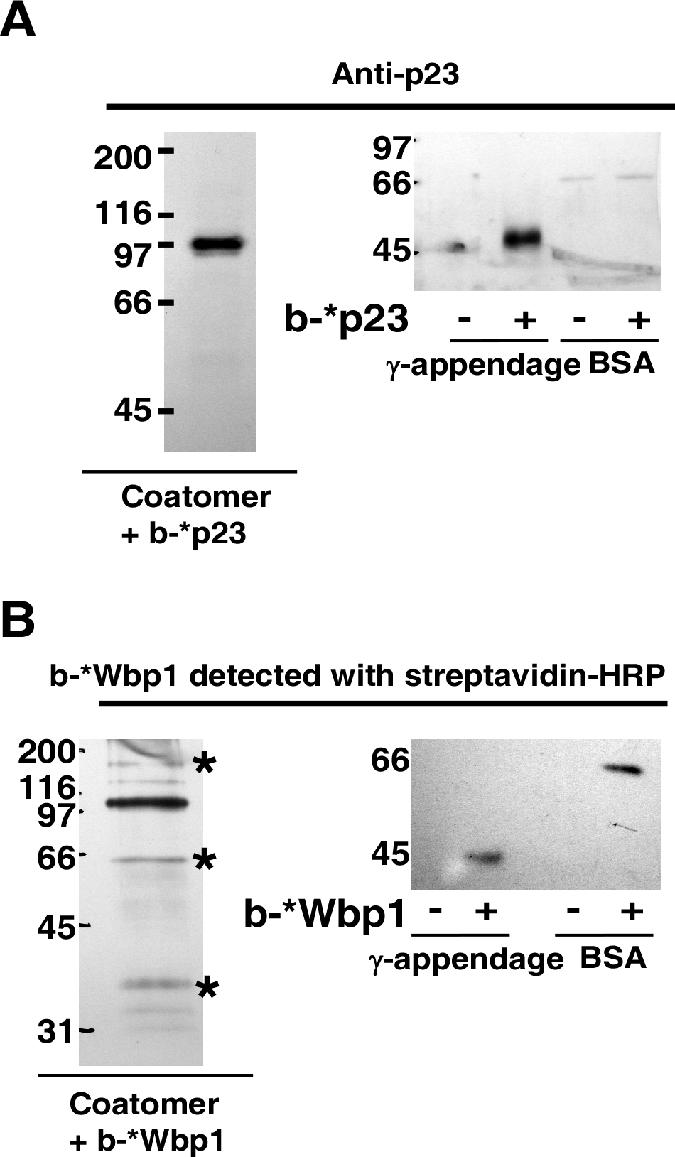

ER-resident cargo proteins bind to coatomer as monomers but not to γ-COP.

We next analyzed the binding of cytoplasmic tails of ER-resident proteins that carry a KKXX signature for retrieval to the ER. Wbp1 and OST48 are present as single copies in the oligosaccharyl transferase complex in yeast and that in mammals, respectively (20, 21, 40). The same is true for DPM2 in the dolichol-phosphate-mannose synthase complex (25). Therefore, the corresponding fusion proteins were constructed as monomers. Consistent with the pull-down experiments shown in Fig. 1, no binding to γ-COP could be detected for these constructs (Fig. 6A, panel 1). However, the monomeric cargo constructs bound to native coatomer (Fig. 6A, panel 2, for example) with affinities comparable to those of p24 family members (Fig. 6B). Since we had reported, based on cross-linking experiments, the binding of Wbp1 to γ-COP (14), we decided to verify the specificity of the photoactivable peptide we had used in this study. Therefore, biotinylated photoactivable Wbp1 or p23 peptides were used for cross-linking experiments with coatomer, γ-COP appendage domain, or BSA. As expected, the photoactivable p23 peptide could be cross-linked to γ-COP within coatomer and to the recombinant appendage domain but not to BSA (Fig. 7A). Strikingly, and in contrast to the photoactivable p23 peptide, the photoactivable Wbp1 peptide could be cross-linked not only to coatomer (mostly to γ-COP) but also to the recombinant appendage domain and even to BSA with similar efficiencies (Fig. 7B). Therefore, the photoactivable Wbp1 peptide does not reflect the behavior of the wild-type peptide, and its cross-linked products cannot be taken as specific. This unexpected lack of specificity led us to misidentify γ-COP as the binding partner of KKXX signal sequence bearing proteins (14). On the other hand, several reports described interactions between the KKXX motif and the α or β′ coatomer subunits (24, 45). In particular, single point mutations of α-COP or β′-COP were shown to be sufficient to disrupt coatomer binding to KKXX motifs (8). However, in this study, the binding of the KKXX signal to γ-COP could not be analyzed for technical reasons. The data presented here show that ER retrieval motifs do not bind to γ-COP. Therefore, α-COP and β′-COP are the only coatomer subunits that interact with monomeric KKXX signatures. As expected, the observed binding of monomeric p25 (the only p24 protein with a KKXX sequence) to coatomer, but not to γ-COP, is also mediated by the α- and β′-COP sites. Indeed, binding to coatomer of monomeric p25 was efficiently competed by an excess of monomeric Wbp1, whereas dimeric p27, which like the other p24 proteins has no KKXX sequence, was not significantly affected (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 7.

The photoactivable peptide b-*Wbp1 is not as specific as b-*p23. (A) Left: Coatomer at 0.1 μM was incubated with 50 μM biotinylated *p23 photoactivable peptide. After UV-induced cross-linking, the sample was immunoprecipitated with an antibody directed against native coatomer. The sample was then eluted and dissociated with 8 M urea. It was then diluted and incubated with streptavidin-coupled beads in order to purify the cross-linked products. The streptavidin-bound material was then analyzed by Western blotting with an antibody against p23. Right: BSA or γ-appendage at 0.5 μM was mixed with 50 μM of *p23 photoactivable peptide and, after UV-induced cross-linking, was analyzed by Western blotting with an antibody against p23. (B) The experiment was performed as described for panel A except that the biotinylated *Wbp1 photoactivable peptide (b-*Wbp1) was used. The asterisks mark the bands that are probably α-, δ-, and ɛ-COP (from top to bottom). Note that in contrast to b-*p23, b-*Wbp1 showed poor specificity, as it could be cross-linked to multiple coatomer subunits, to the γ-appendage domain, and to BSA. Numbers on the left sides of the gels indicate molecular masses.

The higher affinity of dimeric p25 for coatomer than for γ-COP (KD of 0.5 μM versus 10 μM) may therefore be explained by its ability to bind not only to the γ-COP sites but also to both cargo binding sites on α- and β′-COP. Indeed if a dimer of p25 could bind to α- and β′-COP simultaneously, the resulting avidity of such an interaction would be significantly higher than the affinity of each individual interaction. If this was true, a total of three dimeric p25 tails would bind to coatomer at the same time: two to γ-COP and one bridging α- and β′-COP. It would then be predicted that in the presence of an excess of monomeric p25, the two dimeric p25 tails bound to γ-COP would not be affected, while the third dimer bound to α- and β′-COP would be competed out. This was indeed observed. In the presence of an excess of monomeric p25 peptide, the amount of dimeric p25 fusion protein bound to coatomer was reduced by 28% (Fig. 6D), close to the expected one-third reduction that would result from the competition of one of three dimers.

ERGIC-53 binds to coatomer similarly to p24 proteins.

The behavior of a non-ER-resident protein bearing a KKXX sequence was then tested. To this end, a fusion protein harboring the cytoplasmic tail of the lectin ERGIC-53 was used. ERGIC-53 cycles between the ER and the cis-Golgi apparatus and is mostly found in the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment at steady state (37). It forms hexamers through disulfide bounding. This oligomerization is required for the protein to efficiently exit the ER (30). ERGIC-53 is recycled back to the ER by the COPI machinery through interaction with coatomer mediated by its KKXX motif. A dimeric ERGIC-53 construct could bind to γ-COP trunk and appendage domains to an extent similar to that for p24 proteins (Fig. 5). The fusion protein bound full-length γ-COP to the same extent as the individual subdomains, with no evidence of cooperativity. Dimeric ERGIC-53 tails bound to coatomer significantly more tightly than to γ-COP, suggesting the usage of an additional binding site. Since dimers of ERGIC-53 and p25 behaved similarly, the binding of monomeric ERGIC-53 to coatomer was also tested, but it could not be detected (not shown). This might reflect the previously reported poor affinity of the KKFF motif of ERGIC-53 compared to those of other KKXX motifs (19).

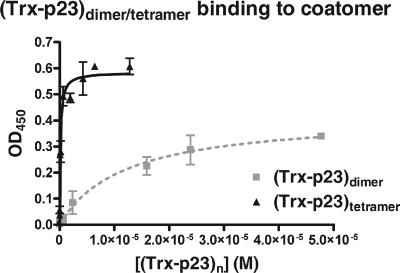

Clustering of p23 tails induces increased avidity for coatomer.

The presence of two discrete binding sites for dimeric tails of p24 proteins on γ-COP raised the question as to whether both sites can be occupied simultaneously. This possibility likely exists because the two domains of γ-COP are predicted to be connected via a flexible hinge region. If coatomer could simultaneously bind to two dimers on a membrane, the apparent overall affinity of such an interaction would be expected to be significantly higher than the affinity of each individual interaction. To model this situation, which would correspond to a cluster of dimeric p24 proteins, we used in our binding assay a tetramerized construct harboring four p23 cytoplasmic tails (see Materials and Methods). As shown in Fig. 8, coatomer binds to this construct with an affinity 100-fold higher than that of the dimeric fusion protein (0.13 μM compared to 12 μM), indicating that simultaneous interaction mediated by both sites is indeed possible and leads to an apparently tighter binding due to an increased avidity.

FIG. 8.

Clustering of p23 tails induces increased avidity for coatomer. Coatomer was analyzed in the microplate-based assay for its binding to (Trx-p23)dimer or to (Trx-p23)tetramer. The corresponding data were plotted with the software PRISM (Graphpad) and were fitted to a hyperbole. Error bars represent the SEM calculated from at least three independent experiments. OD450, optical density at 450 nm.

DISCUSSION

ER-resident proteins and p24 proteins bind to coatomer differently.

Our findings demonstrate the existence of two different mechanisms that allow binding of dibasic motifs to coatomer. Thus, there are two classes of dibasic signatures: those of ER-resident proteins (the KKXX sequence) and those of constitutively cycling proteins of the p24 family [the FFXXBB(X)n motif, where n is ≥2]. The binding sites for these proteins reside in different subunits of coatomer. All p24 cytoplasmic domains bind to γ-COP at two individual binding sites, one in the appendage and one in the trunk domain. Moreover, they all bind to these sites exclusively as dimers. The presence of two binding sites that both bind to dimers is in agreement with the 4:1 stoichiometry of p23 tails bound to coatomer found in another in vitro binding assay (34). The binding of each of the p24 family members to γ-COP is in agreement with their sharing a FFXXBB(X)n motif and the presence of all members in COPI vesicles (27). In contrast, dilysine motifs of ER-resident proteins cannot bind to the γ-COP sites. Instead, they interact as monomers with their established binding sites within the α- and β′-COP WD40 propeller domains (8). Intriguingly, the cytoplasmic tail of ERGIC-53, though containing a classical KKXX motif, behaved very much like p24 family members and not like ER-resident tails. This suggests that the KKXX motifs of constitutively cycling proteins might contain additional signals that give access to the binding sites on γ-COP. However, the exact mechanism by which ERGIC-53 binds to coatomer in vivo needs more investigation, as the protein forms a stable hexamer (37) that might behave differently than the dimeric tails we tested.

Interestingly, with Saccharomyces cerevisiae, overexpression of the yeast p24, but not of Wbp1, can rescue the phenotype of the sec21-3 allele (35). SEC21 encodes the yeast γ-COP, and the sec21-3 strain is defective in COPI vesicle formation at the restrictive temperature (35). These observations point to a relevance of the different binding sites we describe in the context of COPI vesicle packaging.

Functional consequences of the binding of dimeric p24 proteins.

Our data suggest that except for p25 (see below), only dimers of p24 proteins are efficiently taken up in COPI vesicles. Indeed, within the early secretory pathway, p24 proteins are found in dynamic equilibrium between their monomeric and dimeric states (18), and since only dimeric forms bind to coatomer, this equilibrium may control the access of p24 proteins to COPI vesicles. However, this hypothesis still needs to be addressed directly in a cell-free budding assay. Oligomerization seems to be a hallmark of constitutively cycling proteins of the early secretory pathway, as ERGIC-53 is a stable hexamer (37) and the KDEL receptor oligomerizes upon binding to its ligands (26). In the latter case, oligomerization might ensure that only cargo-loaded KDEL receptors are transported back to the ER. What regulates the dimerization of p24 proteins is still unknown. Therefore, it will be of high interest to identify any ligand or posttranslational modification of these proteins that influences their oligomeric state.

The two binding sites on γ-COP work independently.

The existence of two binding sites raised the question of a possible cooperative effect between trunk and appendage domains. However, such an allosteric effect can be excluded based on the following observations. (i) The affinities within complete coatomer and full-length γ-COP are similar to those in the individual trunk and appendage domains (except p25, which will be addressed below). (ii) Both binding sites within coatomer are used to similar extents. (iii) The value of the Hill coefficient derived from coatomer binding experiments is close to 1. Thus, the binding sites present on the trunk and appendage domains of γ-COP work independently, and not in a cooperative manner. We have shown that a preformed tetramer of p23 tails binds significantly more tightly to coatomer than corresponding dimers do. This effect was expected, as a tetramer provides a “double dimer” that γ-COP can bind twice simultaneously with its two sites and thus with an increased avidity due to the synergy of two concurrent weaker interactions. This mode of interaction provides strong yet reversible binding of the coat to p24 proteins, allowing coatomer to continuously sample its membrane environment. It is noteworthy that tetramers of p24 proteins would not be required to induce avid binding, as the flexible linker between trunk and appendage domains should allow both domains to be separated by 10 nm or more if fully extended. Therefore, clustering of p24 protein dimers in a limited area would be enough to engage both γ-COP binding sites simultaneously and dock coatomer more firmly to the membrane.

p25 has the properties of both p24 proteins and ER residents.

We have shown that p25 is unique within the p24 family because it can bind to γ-COP as a dimer and to the binding sites for ER-resident cargo proteins as a monomer. This was expected, as p25 is the only p24 family member that has a “true” KKXX retrieval sequence within its FFXXBB(X)n motif. Dimers of p25 tails exhibited a much stronger binding to coatomer than to γ-COP (Fig. 4). We have shown that when presented as a dimer, p25 is likely able to bridge both KKXX binding sites on α- and β′-COP, in addition to binding the two sites on γ-COP. This would explain the apparently tighter binding (KD ≈ 0.5 μM) of this interaction. The FFXXBB(X)n motif has been suggested to function as a signal for anterograde transport, as opposed to the KKXX motif, which is used for retrieval (10). As p24 proteins are in dynamic equilibrium with each other to form homo- and heterodimers (18), it is tempting to suggest that p25 prevents other p24 proteins from escaping the early secretory pathway by forming heterodimers with other members of the family. Such a heterodimer (e.g., of p25 and p24) might then be retrieved to the early secretory pathway through interaction of its monomeric p25 part with the α- or β′-COP cargo binding sites. Accordingly, it has been shown in vivo that expressing a p25 mutant lacking its dilysine motif leads to mislocalization of the mutant as well as other p24 family members to the plasma membrane (7). Such a mechanism would imply the abundance of p25 within the Golgi to be significantly higher than that of other p24 family members. We did not observe such a difference in a previous estimation of the concentration of p24 proteins within the early secretory pathway (18). Therefore, the exact contribution of p25 for the retention of the p24 family will need to be carefully evaluated in vivo and may well be based upon various affinities and/or transport kinetics.

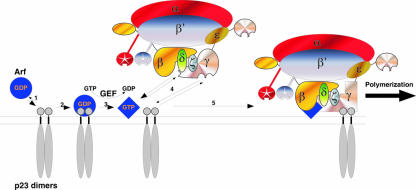

A model for the sorting of p24 proteins into COPI vesicles.

Recruitment of coatomer to Golgi membranes depends on an interaction with the small GTPase Arf1 in its GTP-bound form (31). Previously, it was shown that GDP-bound Arf is recruited to Golgi membranes via dimers of p23 (13, 26). The resulting complex becomes dissociated after Arf activation by nucleotide exchange and thus transiently places p23 dimers and activated Arf in close vicinity, making them available to be bound by coatomer. Activated Arf or p24 proteins alone do not bind tightly enough to coatomer to efficiently recruit the complex to membranes but rather act synergistically (2). Thus, we propose that coatomer, through its weak binding sites for dimeric p24 proteins, can continuously sample the Golgi membrane. Since γ-COP has binding sites for both Arf-GTP and p24 proteins (46), and since p23 dimers are able to localize Arf activation in their vicinity, coatomer will preferentially bind to Golgi membranes via simultaneous interaction with Arf-GTP and dimers of p23 (Fig. 9). With this multivalent interaction, coatomer should then be stably bound to the membrane, a prerequisite for vesicle formation. It is important to note that in contrast to the situation for anterograde and retrograde cargo proteins, which depend on GTP hydrolysis by Arf in order to enter COPI vesicles, the uptake of p24 proteins and other cycling proteins into COPI vesicles is not affected when GTP hydrolysis is blocked (28, 33). This is consistent with our model, since sorting of p23 occurs before the activation of Arf.

FIG. 9.

A model for the sorting of p24 proteins into COPI vesicles. p23 dimers can recruit Arf-GDP (blue disk) to the membrane (1), allowing nucleotide exchange (2). Once bound to GTP, Arf-GTP (blue square) dissociates from the p23 dimer (3). Coatomer can simultaneously bind to Arf-GTP and the dimer of p23 (4). This results in the stable association of coatomer to membranes (5) and allows the coat to polymerize to build a lattice and eventually form a vesicle. Note that if GTP was replaced by a nonhydrolyzable analog, all the steps would be unchanged.

In conclusion, we have shown that coatomer binds to ER-resident cargo proteins and to the constitutively cycling p24 proteins differently. These differential interactions involve different subunits and in the case of p24 family members require dimerization of the proteins. It remains to be addressed if the above-described model applies to all the p24 proteins and more generally to other cycling proteins, such as ERGIC-53 or the KDEL receptor. This is of particular interest as constitutively cycling proteins of the early secretory pathway have the property to oligomerize and usually have a dibasic motif different from the canonical KKXX sequence.

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas Söllner and Patricia McCabe for critical comments on the manuscript and Blanche Schwappach and Ed Hurt for providing plasmids. We thank Martina Haucke for technical help.

This work was supported by a grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 638).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 August 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bornstein, P., and G. Balian. 1977. Cleavage at Asn-Gly bonds with hydroxylamine. Methods Enzymol. 47:132-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bremser, M., W. Nickel, M. Schweikert, M. Ravazzola, M. Amherdt, C. A. Hughes, T. H. Sollner, J. E. Rothman, and F. T. Wieland. 1999. Coupling of coat assembly and vesicle budding to packaging of putative cargo receptors. Cell 96:495-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Contreras, I., E. Ortiz-Zapater, and F. Aniento. 2004. Sorting signals in the cytosolic tail of membrane proteins involved in the interaction with plant ARF1 and coatomer. Plant J. 38:685-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cosson, P., and F. Letourneur. 1994. Coatomer interaction with di-lysine endoplasmic reticulum retention motifs. Science 263:1629-1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dominguez, M., K. Dejgaard, J. Fullekrug, S. Dahan, A. Fazel, J. P. Paccaud, D. Y. Thomas, J. J. Bergeron, and T. Nilsson. 1998. gp25L/emp24/p24 protein family members of the cis-Golgi network bind both COP I and II coatomer. J. Cell Biol. 140:751-765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duden, R., G. Griffiths, R. Frank, P. Argos, and T. E. Kreis. 1991. Beta-COP, a 110 kd protein associated with non-clathrin-coated vesicles and the Golgi complex, shows homology to beta-adaptin. Cell 64:649-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emery, G., R. G. Parton, M. Rojo, and J. Gruenberg. 2003. The trans-membrane protein p25 forms highly specialized domains that regulate membrane composition and dynamics. J. Cell Sci. 116:4821-4832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eugster, A., G. Frigerio, M. Dale, and R. Duden. 2004. The alpha- and beta'-COP WD40 domains mediate cargo-selective interactions with distinct di-lysine motifs. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:1011-1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faulstich, D., S. Auerbach, L. Orci, M. Ravazzola, S. Wegchingel, F. Lottspeich, G. Stenbeck, C. Harter, F. T. Wieland, and H. Tschochner. 1996. Architecture of coatomer: molecular characterization of delta-COP and protein interactions within the complex. J. Cell Biol. 135:53-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiedler, K., M. Veit, M. A. Stamnes, and J. E. Rothman. 1996. Bimodal interaction of coatomer with the p24 family of putative cargo receptors. Science 273:1396-1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fligge, T. A., C. Reinhard, C. Harter, F. T. Wieland, and M. Przybylski. 2000. Oligomerization of peptides analogous to the cytoplasmic domains of coatomer receptors revealed by mass spectrometry. Biochemistry 39:8491-8496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldberg, J. 2000. Decoding of sorting signals by coatomer through a GTPase switch in the COPI coat complex. Cell 100:671-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gommel, D. U., A. R. Memon, A. Heiss, F. Lottspeich, J. Pfannstiel, J. Lechner, C. Reinhard, J. B. Helms, W. Nickel, and F. T. Wieland. 2001. Recruitment to Golgi membranes of ADP-ribosylation factor 1 is mediated by the cytoplasmic domain of p23. EMBO J. 20:6751-6760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harter, C., J. Pavel, F. Coccia, E. Draken, S. Wegehingel, H. Tschochner, and F. Wieland. 1996. Nonclathrin coat protein gamma, a subunit of coatomer, binds to the cytoplasmic dilysine motif of membrane proteins of the early secretory pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:1902-1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harter, C., and F. T. Wieland. 1998. A single binding site for dilysine retrieval motifs and p23 within the gamma subunit of coatomer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:11649-11654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffman, G. R., P. B. Rahl, R. N. Collins, and R. A. Cerione. 2003. Conserved structural motifs in intracellular trafficking pathways: structure of the gammaCOP appendage domain. Mol. Cell 12:615-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson, M. R., T. Nilsson, and P. A. Peterson. 1990. Identification of a consensus motif for retention of transmembrane proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 9:3153-3162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenne, N., K. Frey, B. Brugger, and F. T. Wieland. 2002. Oligomeric state and stoichiometry of p24 proteins in the early secretory pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 277:46504-46511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kappeler, F., D. R. Klopfenstein, M. Foguet, J. P. Paccaud, and H. P. Hauri. 1997. The recycling of ERGIC-53 in the early secretory pathway. ERGIC-53 carries a cytosolic endoplasmic reticulum-exit determinant interacting with COPII. J. Biol. Chem. 272:31801-31808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karaoglu, D., D. J. Kelleher, and R. Gilmore. 1997. The highly conserved Stt3 protein is a subunit of the yeast oligosaccharyltransferase and forms a subcomplex with Ost3p and Ost4p. J. Biol. Chem. 272:32513-32520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelleher, D. J., D. Karaoglu, E. C. Mandon, and R. Gilmore. 2003. Oligosaccharyltransferase isoforms that contain different catalytic STT3 subunits have distinct enzymatic properties. Mol. Cell 12:101-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirchhausen, T., K. L. Nathanson, W. Matsui, A. Vaisberg, E. P. Chow, C. Burne, J. H. Keen, and A. E. Davis. 1989. Structural and functional division into two domains of the large (100- to 115-kDa) chains of the clathrin-associated protein complex AP-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:2612-2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, M. C., E. A. Miller, J. Goldberg, L. Orci, and R. Schekman. 2004. Bi-directional protein transport between the ER and Golgi. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20:87-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Letourneur, F., E. C. Gaynor, S. Hennecke, C. Demolliere, R. Duden, S. D. Emr, H. Riezman, and P. Cosson. 1994. Coatomer is essential for retrieval of dilysine-tagged proteins to the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 79:1199-1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maeda, Y., S. Tanaka, J. Hino, K. Kangawa, and T. Kinoshita. 2000. Human dolichol-phosphate-mannose synthase consists of three subunits, DPM1, DPM2 and DPM3. EMBO J. 19:2475-2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Majoul, I., M. Straub, S. W. Hell, R. Duden, and H. D. Soling. 2001. KDEL-cargo regulates interactions between proteins involved in COPI vesicle traffic: measurements in living cells using FRET. Dev. Cell 1:139-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malsam, J., A. Satoh, L. Pelletier, and G. Warren. 2005. Golgin tethers define subpopulations of COPI vesicles. Science 307:1095-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nickel, W., J. Malsam, K. Gorgas, M. Ravazzola, N. Jenne, J. B. Helms, and F. T. Wieland. 1998. Uptake by COPI-coated vesicles of both anterograde and retrograde cargo is inhibited by GTPgammaS in vitro. J. Cell Sci. 111:3081-3090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nickel, W., K. Sohn, C. Bunning, and F. T. Wieland. 1997. p23, a major COPI-vesicle membrane protein, constitutively cycles through the early secretory pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:11393-11398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nufer, O., F. Kappeler, S. Guldbrandsen, and H. P. Hauri. 2003. ER export of ERGIC-53 is controlled by cooperation of targeting determinants in all three of its domains. J. Cell Sci. 116:4429-4440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palmer, D. J., J. B. Helms, C. J. Beckers, L. Orci, and J. E. Rothman. 1993. Binding of coatomer to Golgi membranes requires ADP-ribosylation factor. J. Biol. Chem. 268:12083-12089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pavel, J., C. Harter, and F. T. Wieland. 1998. Reversible dissociation of coatomer: functional characterization of a beta/delta-coat protein subcomplex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:2140-2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pepperkok, R., J. A. Whitney, M. Gomez, and T. E. Kreis. 2000. COPI vesicles accumulating in the presence of a GTP restricted arf1 mutant are depleted of anterograde and retrograde cargo. J. Cell Sci. 113:135-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reinhard, C., C. Harter, M. Bremser, B. Brugger, K. Sohn, J. B. Helms, and F. Wieland. 1999. Receptor-induced polymerization of coatomer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:1224-1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sandmann, T., J. M. Herrmann, J. Dengjel, H. Schwarz, and A. Spang. 2003. Suppression of coatomer mutants by a new protein family with COPI and COPII binding motifs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 14:3097-3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schledzewski, K., H. Brinkmann, and R. R. Mendel. 1999. Phylogenetic analysis of components of the eukaryotic vesicle transport system reveals a common origin of adaptor protein complexes 1, 2, and 3 and the F subcomplex of the coatomer COPI. J. Mol. Evol. 48:770-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schweizer, A., J. A. Fransen, T. Bachi, L. Ginsel, and H. P. Hauri. 1988. Identification, by a monoclonal antibody, of a 53-kD protein associated with a tubulo-vesicular compartment at the cis-side of the Golgi apparatus. J. Cell Biol. 107:1643-1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Serafini, T., G. Stenbeck, A. Brecht, F. Lottspeich, L. Orci, J. E. Rothman, and F. T. Wieland. 1991. A coat subunit of Golgi-derived non-clathrin-coated vesicles with homology to the clathrin-coated vesicle coat protein beta-adaptin. Nature 349:215-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sohn, K., L. Orci, M. Ravazzola, M. Amherdt, M. Bremser, F. Lottspeich, K. Fiedler, J. B. Helms, and F. T. Wieland. 1996. A major transmembrane protein of Golgi-derived COPI-coated vesicles involved in coatomer binding. J. Cell Biol. 135:1239-1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spirig, U., M. Glavas, D. Bodmer, G. Reiss, P. Burda, V. Lippuner, S. te Heesen, and M. Aebi. 1997. The STT3 protein is a component of the yeast oligosaccharyltransferase complex. Mol. Gen. Genet. 256:628-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stamnes, M. A., M. W. Craighead, M. H. Hoe, N. Lampen, S. Geromanos, P. Tempst, and J. E. Rothman. 1995. An integral membrane component of coatomer-coated transport vesicles defines a family of proteins involved in budding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:8011-8015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waters, M. G., T. Serafini, and J. E. Rothman. 1991. ‘Coatomer’: a cytosolic protein complex containing subunits of non-clathrin-coated Golgi transport vesicles. Nature 349:248-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watson, P. J., G. Frigerio, B. M. Collins, R. Duden, and D. J. Owen. 2004. Gamma-COP appendage domain—structure and function. Traffic 5:79-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuan, H., K. Michelsen, and B. Schwappach. 2003. 14-3-3 dimers probe the assembly status of multimeric membrane proteins. Curr. Biol. 13:638-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zerangue, N., M. J. Malan, S. R. Fried, P. F. Dazin, Y. N. Jan, L. Y. Jan, and B. Schwappach. 2001. Analysis of endoplasmic reticulum trafficking signals by combinatorial screening in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:2431-2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao, L., J. B. Helms, J. Brunner, and F. T. Wieland. 1999. GTP-dependent binding of ADP-ribosylation factor to coatomer in close proximity to the binding site for dilysine retrieval motifs and p23. J. Biol. Chem. 274:14198-14203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]