Abstract

We developed a retrovirus-based protein-fragment complementation assay (RePCA) screen to identify protein–protein interactions in mammalian cells. In RePCA, bait protein is fused to one fragment of a rationally dissected fluorescent protein, such as GFP, intensely fluorescent protein, or red fluorescent protein. The second, complementary fragment of the fluorescent protein is fused to an endogenous protein by in-frame exon traps in the enhanced retroviral mutagen vector. An interaction between bait and host protein (prey) places the two parts of the fluorescent molecule in proximity, resulting in reconstitution of fluorescence. By using RePCA, we identified a series of 24 potential interaction partners or substrates of the serine/threonine protein kinase AKT1. We confirm that α-actinin 4 (ACTN4) interacts physically and functionally with AKT1. siRNA-mediated ACTN4 silencing down-regulates AKT phosphorylation, blocks AKT translocation to the membrane, increases p27Kip1 levels, and inhibits cell proliferation. Thus, ACTN4 is a critical regulator of AKT1 localization and function.

Keywords: α-actinin 4, AKT1, protein–protein interactions, screen

Presently, novel protein–protein interactions are identified by using yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) systems (1), coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and mass spectrometry (2), or protein libraries (3). These approaches, however, do not efficiently identify protein interactions on the cytoskeleton or membrane, either because of the location of the interaction (Y2H) or difficulties in the Co-IP of cytoskeletal or membrane proteins. Furthermore, conventional Y2H approaches yield false-positive signals with transcription factors precluding screening. The purpose of this study was to develop a readily applicable, subcellular localization-, library-, and cell-independent method for the identification of protein–protein interactions, including cytoskeletal and membrane proteins, in mammalian cells and apply it to the well characterized AKT protooncogene.

The retrovirus-based protein-fragment complementation assay (RePCA) utilizes the technical advantages of two emerging technologies, the enhanced retroviral mutagen (ERM) vector and the protein-fragment complementation assay (PCA). The ERM vector functions as an exon trap that efficiently activates and tags endogenous genes (4). The ERM vector in all three ORFs can be applied to any mammalian cell without the effort and bias of cell-specific libraries. Furthermore, the ERM vector utilizes the endogenous splicing machinery of the target cell, allowing the evaluation of variations in natural splice variants. In PCA, a reporter protein, such as a monomeric enzyme or a fluorescent protein (GFP or a variant thereof), is rationally dissected into two fragments that will not reconstitute spontaneously (5–7). When each fragment of the fluorescent protein is fused to one of a pair of interacting protein partners, the subsequent protein binding places the fragments in proximity, creating a functional complex that restores fluorescence levels to near that of the parental molecule (8). Recently, Remy and Michnick (9) identified an AKT1 partner with a PCA-based cDNA library screen using GFP as a reporter. However, the need to generate cell-specific cDNA libraries and a complex approach to the identification of candidates renders this approach technically demanding and labor-intensive. RePCA combines the power of ERM (4) with PCA (8) to provide a facile, sensitive approach for the identification of context-dependent protein–protein interactions in mammalian cells, allowing native protein folding and posttranslational modifications.

Results

RePCA Screen Design.

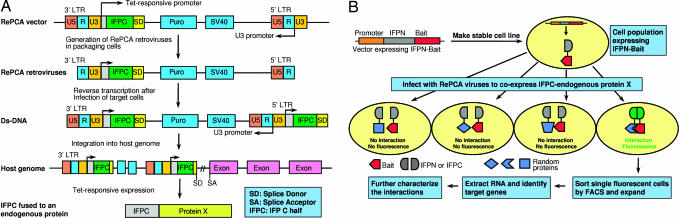

The intensely fluorescent protein (IFP), also known as Venus (10), was dissected into two fragments, an IFP N-terminal portion (IFPN) and IFP C-terminal portion (IFPC), at residue 158 (11). As shown in Fig. 1A, IFPC was inserted into the ERM vector, followed by a splice donor, to construct the RePCA vector. A Tet-responsive promoter obviates potential toxicity of the fusion protein. After infection of the target cells, the retrovirus undergoes reverse transcription and integration into the host genome. If the integration occurs upstream or inside a host gene, the splice donor in the RePCA vector generates a fusion transcript with IFPC linked in-frame to downstream host exons. The propensity of the ERM retrovirus to integrate near the start of transcriptional units increases the chance that a full-length or near-full-length fusion protein will be created (12).

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the RePCA screen. (A) Generation of IFPC fusion with endogenous proteins in mammalian cells. A RePCA vector is constructed by inserting IFPC into the ERM retroviral vector, followed by a splice donor, in the U3 region of the 3′ LTR. A Tet-responsive promoter controls the expression of IFPC. RePCA retroviruses are generated in packaging cells. After the infection of target cells, integration upstream or inside a host gene may allow the generation of in-frame IFPC fusions with a host protein (see Results for details). (B) Procedures of the RePCA screen. Bait is fused to IFPN. A host cell line, preferably containing the Tet regulatory complex to enable the expression from a Tet-responsive promoter, is transfected to stably express IFPN-Bait. The cell population is infected with RePCA viruses to create endogenous protein fusions with IFPC. Fusion of IFPC in-frame to a protein that binds the bait reconstitutes the IFP molecule, restoring fluorescence. Fluorescent cells are cloned by cell sorting or other approaches and expanded, and target genes are identified by RT-PCR.

A host cell line expressing the tetracycline-regulated transactivator tTA or reverse tTA to enable the regulated expression of the prey from the Tet-responsive promoter is generated by transfection to express the IFPN-Bait fusion protein (Fig. 1B). Bait fusion protein-expressing cells are infected with the RePCA retrovirus in all three frames to generate in-frame IFPC-endogenous fusion proteins. Cells in which the retrovirus does not generate an in-frame fusion protein or wherein IFPC is not fused to a binding partner of the bait do not fluoresce. Only cells containing IFPC fused in-frame to an interaction partner of the bait fluoresce. The fluorescent cells are cloned, and the target genes are identified by RT-PCR with primers contained in the ERM vector. The resulting fluorescent clones can be directly used to characterize the formation, localization, and functionality of candidate interactions, providing powerful reagents for mechanistic exploration without the need for recloning.

Proof-of-Concept Screen for AKT1 Interaction Partners.

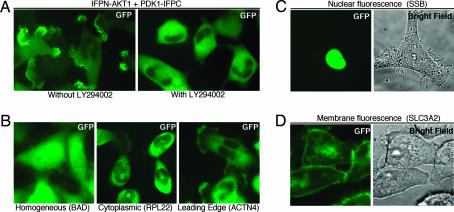

We chose AKT1 (also known as PKB-α), which plays a central role in cell metabolism, survival, growth, and tumorigenesis (13, 14), as a bait for a proof-of-concept RePCA screen. IFPN-AKT1 HeLa Tet-on cells with or without transient transfection of IFPC were not fluorescent, confirming that the fragments do not fluoresce and do not spontaneously associate (data not shown). Transfection of the known AKT partner, phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1)-IFPC (15), into IFPN-AKT1 HeLa Tet-on cells resulted in fluorescence, which was enriched in the cell membrane and at points of cell–cell contact (Fig. 2A). The membrane localization of the PDK1-IFPC:IFPN-AKT1 complex was completely blocked by inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K) with LY294002, as expected from the known localization of AKT1 and PDK1 (16, 17). Thus, linking each part of IFP to interacting proteins AKT1 and PDK1 reconstitutes IFP fluorescence with appropriate subcellular localization.

Fig. 2.

Pilot screen for AKT1-interaction partners. (A) AKT1 interaction with PDK1 demonstrated by PCA. IFPN-AKT1 HeLa Tet-on cells stably transfected to coexpress PDK1-IFPC yielded highly fluorescent cells with enhanced fluorescence at the cell membrane and points of cell–cell contact. Inhibition of PI3K with LY294002 (20 μM) for 3 hr abrogated membrane localization. (B) Selected RePCA clones with different fluorescent patterns. Expanded clones were assessed for fluorescence after doxycycline induction. The target genes activated in each clone are shown under each image. (C) SSB clone (Table 1, no. 20) showing nuclear fluorescence. (D) SLC3A2 (Table 1, no. 6) clone showing membrane fluorescence.

IFPN-AKT1 HeLa Tet-on cells were separately infected with RePCA-IFPC retroviral vectors in all three reading frames. After selection with puromycin and induction with doxycycline, single fluorescent cells were isolated by sorting. Expanded clones displayed fluorescence with different patterns, i.e., homogenous, cytoplasmic, nuclear, or membrane, suggesting differential localization of AKT1 and specific binding partners (see Fig. 2 B–D and Table 1). We chose 70 fluorescent clones for identification of target genes (10, 30, and 30 clones for reading frame 1, 2, and 3, respectively), all of which yielded fusion transcripts. In terms of efficiency, using frame 2 as an example, 2 × 107 cells were sorted, with the 384 most highly fluorescent cells placed in single wells. Doxycycline was withdrawn to reduce the expression of proteins that could have adverse effects on cell survival and growth. Of the 384 cells sorted, 120 cells (≈30%) formed colonies, with 55 colonies showing fluorescence after doxycycline induction (≈14%). We chose 30 clones based on fluorescence intensity and patterns and identified 11 independent candidate AKT1 partners (Table 1). Thus, from 2 × 107 cells, 11 candidates were identified. This pilot screen was not taken to saturation; therefore, it is likely that additional AKT1-binding partners would be identified in large-scale screens. Twenty-four independent candidates were identified from all three ORFs (Table 1). Some candidates were present as multiple clones [i.e., BCL2-antagonist of cell death (BAD) was identified three times (Table 1)] and were likely derived from a single infected parental cell that divided before cell sorting, because sequencing demonstrated identical fusion transcripts. Limiting cell propagation before sorting fluorescent cells could increase the target diversity identified in the screen. IFPC fusion proteins similar to calculated sizes were detected in all clones (see Fig. 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, for selected clones) except for AHNAK2, which has an expected molecular weight of >600 kDa, precluding detection by Western blots. The identification of AHNAK2 demonstrates the power of the ERM vector, which, through the use of endogenous splicing machinery, is not restricted in terms of size of insert. In 14 of 24 clones, the IFPC fragment was fused to a full-length or near-full-length protein (Table 1).

Table 1.

Interaction partners of AKT1 identified in RePCA screen

| No. | Protein name | Gene symbol | Vector reading frame | Insertion site, aa | Expected size of the fusion protein, kDa | No. of clones for the target | Predominant fluorescence localization | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BCL2-antagonist of cell death* | BAD | 2 | 63 | 23 | 3 | Homogenous | NP_116784 |

| 2 | Myosin light chain (atrial/embryonic alkali)* | MYL4 | 3 | −12 | 34 | 1 | Cytoplasm | NP_001002841 |

| 3 | Heme oxygenase 2* | HMOX2 | 2 | −14 | 47 | 2 | Cytoplasm | NP_002125 |

| 4 | C14ORF78* | AHNAK2 | 2 | 167 | 613 | 1 | Cytoplasm, Leading edge | XP_290629 |

| 5 | Activator of heat shock 90-kDa protein ATPase homolog 1* | AHA1 | 3 | 28 | 45 | 2 | Homogenous | NP_036243 |

| 6 | CD98#x002A; | SLC3A2 | 2 | 38 | 80 | 1 | Membrane | NP_001012679 |

| 7 | Moesin* | MSN | 1 | 5 | 74 | 2 | Cytoplasm | NP_002435 |

| 8 | Ribosomal protein L22* | RPL22 | 1 | 5 | 25 | 1 | Cytoplasm | NP_000974 |

| 9 | Reticulon 4*† | RTN4 | 2 | 12 | 32 | 3 | Cytoplasm | NP_008939 |

| 10 | GTPase-activating RANGAP domain-like 3* | GARNL3 | 2 | 897 | 22 | 8 | Homogenous | NP_115669 |

| 11 | Lamin A/C* | LMNA | 3 | 120 | 68 | 1 | Nucleus | NP_733822 |

| 12 | α-Actinin 4* | ACTN4 | 1 | 53 | 105 | 2 | Cytoplasm, Leading edge | NP_004915 |

| 13 | Sterol O-acyltransferase‡ | SOAT1 | 2 | −3 | 72 | 1 | Cytoplasm | NP_003092 |

| 14 | Peroxiredoxin 1‡ | PRDX1 | 2 | −4 | 34 | 5 | Cytoplasm | NP_859047 |

| 15 | Phosphorybosylaminoi midazole carboxylase‡ | PAICS | 2 | 6 | 57 | 2 | Cytoplasm, Leading edge | NP_006443 |

| 16 | Annexin I‡ | ANXA1 | 2 | −5 | 50 | 1 | Homogenous | NP_000691 |

| 17 | Protease inhibitor 6‡ | PI6 | 3 | −4 | 53 | 3 | Homogenous | NP_004559 |

| 18 | ARCHAIN 1‡ | ARCN1 | 3 | 218 | 43 | 1 | Homogenous | NP_001646 |

| 19 | Proteolipid protein 2‡ | PLP2 | 3 | −31 | 31 | 8 | Membrane | NP_002659 |

| 20 | Autoantigen La‡ | SSB | 3 | 186 | 36 | 3 | Nucleus | NP_003133 |

| 21 | Zinc finger protein 185‡ | ZNF185 | 3 | 232 | 35 | 5 | Homogenous | NP_009081 |

| 22 | F-actin-capping protein β subunit‡ | CAPZB | 1 | 2 | 41 | 5 | Cytoplasm | NP_004921 |

| 23 | Protein translation factor SUI1 homolog‡ | Sui1iso1 | 2 | 11 | 22 | 3 | Homogenous | XP_497726 |

| 24 | Pyruvate kinase, muscle‡ | PKM2 | 3 | −93 | 80 | 6 | Cytoplasm | NP_872271 |

Accession nos. and gene symbols are from GenBank.

*Known partners/substrates or potential partners/substrates with known links to AKT.

†RTN4 has five splice variants, A–E, with the same C-terminal sequence. The insertion site for RTN4 was defined according to the RTN4 variant C sequence.

‡Potential AKT partners/substrates without obvious known links to AKT.

Among the targets, BAD is a well characterized AKT substrate and interaction partner (18). Myosin light chain (atrial/embryonic alkali) (MYL4) is part of the myosin II complex, a known AKT-binding partner (19). AHA1, Annexin1, and a Lamin A/C isoform (LaminB1) have been confirmed as AKT-binding partners by Co-IP and mass spectroscopy (J. Downward, personal communication). We also identified two potential AKT substrates because heme oxygenase 2 (HMOX2) and C14ORF78 (AHNAK2) are isoforms of HMOX1 and AHNAK1, which are known AKT substrates (20, 21). Additional candidates have strong links to AKT (Table 1). For example, CD98 regulates AKT phosphorylation and activation (22). Both CD98 and AKT interact with integrin-β1 (22, 23). Moesin and AKT interact with the hamartin:tuberin complex (24–26). The identification of known and likely AKT partners/substrates validates the screening strategy.

α-Actinin 4 (ACTN4) Is a Functional Partner of AKT1.

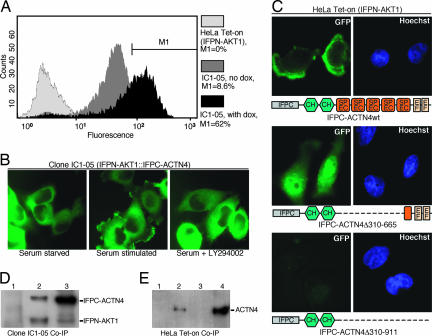

α-Actinin actin-binding proteins, including ACTN4, can bind the p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K and translocate out of the membrane after inhibition of PI3K (27–29). In addition, ACTN4 contributes to the prognosis of breast cancer (29) and has been implicated in tumor development, invasion, and metastases (30, 31), making it a candidate for further characterization. The fluorescence of the ACTN4 clone (IC1-05) obtained from the screen was markedly increased by doxycycline; therefore, formation of the fluorescent complex was controlled by Tet-responsive expression of the IFPC fusion protein (Fig. 3A). The fluorescent IFPN-AKT1::IFPC-ACTN4 complex in clone IC1-05 was located throughout the cytoplasm in serum-starved cells (Fig. 3B). Serum induced the translocation of the AKT1::ACTN4 complex to the membrane, in particular cellular ruffles, reminiscent of the PDK1::AKT1 complex (Fig. 2A), and to the nuclear periphery (Fig. 3B). Compatible with the observation that ACTN4 translocates out of the membrane upon inhibition of PI3K (29), serum-dependent translocation of the AKT1::ACTN4 complex to the cell membrane was blocked by inhibition of PI3K, indicating that membrane localization depended on the production of 3-phosphorylated membrane phosphatidylinositols. Expression of an exogenous IFPC-ACTN4wt in IFPN-AKT1 HeLa Tet-on cells resulted in fluorescence, which was enriched at the leading edge of cells growing in serum (Fig. 3C), confirming that the apparent interaction between ACTN4 and AKT1 was not due to clonal variation. Expression of a IFPC-ACTN4Δ310–665 deletion construct resulted in homogeneous fluorescence in the cytoplasm with enhanced fluorescence in the nucleus but completely failed to mediate localization of the fluorescent complex to the leading edge of cells growing in serum (Fig. 3C). In contrast, coexpression of IFPN-AKT1 and IFPC-ACTN4Δ310–911 did not result in detectable fluorescence (Fig. 3C). Thus, residues 665–911 of ACTN4, which contain two EF motifs, are required for the interaction with AKT1, whereas residues 310–665 of ACTN4 are critical for the localization of the AKT1::ACTN4 complex to the leading edge of cells. Strikingly, the PH domain of AKT1 (32) was not sufficient to translocate the AKT1::ACTN4 complex to the cell membrane, suggesting that ACTN4 contributes to AKT1 localization. However, given that LY294002 blocked translocation (Fig. 3B), the translocation of the AKT1::ACTN4 complex to the membrane depends on the production of 3-phosphorylated membrane phosphatidylinositols. Therefore, the screening approach not only provides insight into the binding partners of AKT1, but the resultant cells can also provide important functional information related to the localization and formation of the protein complexes.

Fig. 3.

AKT1 interaction with ACTN4. (A) The fluorescence intensity of clone IC1-05 (ACTN4) is Tet-responsive. No IFPN-AKT1 HeLa Tet-on cells were in the M1 quadrant. Cells had a mean fluorescence level of 3.2. IC1-05 cells exhibited low-level fluorescence without doxycycline induction, likely because of leaky expression from Tet-responsive promoters (8.6% of cells in M1 quadrant). Cells had a mean fluorescence level of 46.5. After incubation with 2 μg/ml doxycycline for 48 hr, the mean fluorescence of IC1-05 cells increased to 112.9 (62% of cells in the M1 quadrant). (B) Translocation of IFPN-AKT1::IFPC-ACTN4 complex upon serum stimulation in clone IC1-05. Serum-starved cells show predominantly cytoplasmic fluorescence. After serum (10%) stimulation for 60 min, the fluorescent complex translocated to the leading edge of cells and the periphery of the nucleus in >90% of cells. Inhibition of PI3K with a 3-hr treatment of LY294002 (10 μM) abrogated serum-induced membrane localization. At least 100 cells were examined from different fields for each sample. (C) Confirmation of ACTN4::AKT1 interaction by PCA and identification of the residues in ACTN4 required for interaction with AKT1 and localization of the complex. Coexpression of IFPN-AKT1 with IFPC-ACTN4wt yielded fluorescence enriched at the leading edge of the cell (ruffles). Coexpression of IFPN-AKT1 with IFPC-ACTN4Δ310–665 yielded cytoplasmic and enhanced nuclear fluorescence. Coexpression of IFPN-AKT1 with IFPC-ACTN4Δ310–911 did not result in fluorescence. A schematic under each set of images shows the domains in wild-type or deletion mutants of ACTN4. CH, calponin homology domain; SPEC, spectrin repeats; EF, EF-hand, calcium-binding motif. (D) Association of IFPN-AKT1 with IFPC-ACTN4 in clone IC1-05. Clone IC1-05 cells expressing IFPN-AKT1 and IFPC-ACTN4 were lysed in RIPA buffer. Co-IP was performed with anti-AKT1 and Western blotting with anti-GFP. Lane 1, Co-IP with normal IgG; lane 2, Co-IP with anti-AKT1; lane 3, total lysate. (E) Association of AKT1 with ACTN4 in parental HeLa Tet-on cells. HeLa Tet-on cells were lysed in RIPA buffer, with in vivo cross-linking with BASED. Co-IP was performed with anti-AKT1 and Western blotting with anti-ACTN4. Lane 1, Co-IP with normal IgG; lane 2, Co-IP with anti-AKT1; lane 3, blank; lane 4, total lysate.

In clone IC1-05, IFPC-ACTN4 was readily immunoprecipitated by anti-AKT1 antibodies and detected by immunoblotting with a polyclonal anti-GFP antibody, which binds both halves of IFP (Fig. 3D). Equal amounts of IFPC-ACTN4 and IFPC-AKT1 were present in the immunoprecipitated complex, compatible with the formation of a dimer. In parental HeLa Tet-on cells, ACTN4 could be immunoprecipitated by anti-AKT1 antibodies after in vivo cross-linking (Fig. 3E; see also Supporting Materials and Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), demonstrating an association of endogenous AKT1 with ACTN4. We were unable to detect a stable association between endogenous AKT1 and ACTN4 by Co-IP in the absence of cross-linking (data not shown), potentially because the conditions required to efficiently release ACTN4 from the cytoskeleton disrupted interactions between AKT1 and ACTN4 or because the interaction between AKT1 and ACTN4 was transient or indirect.

ACTN4 Silencing Inhibits AKT Translocation, Phosphorylation, Signaling, and Cell Proliferation.

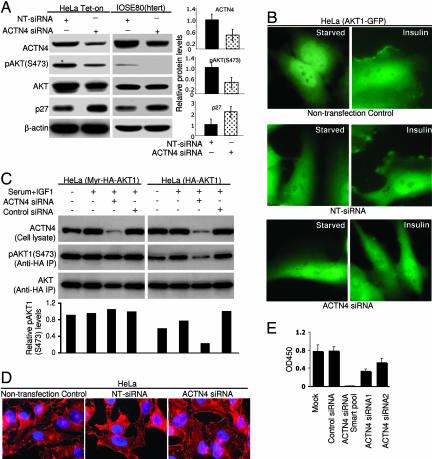

The membrane localization of AKT plays a pivotal role in AKT activation (13, 14). The distinctive pattern of ACTN4::AKT1 complex localization suggested that ACTN4 could contribute to AKT translocation and, thus, activation. In HeLa Tet-on cells as well as in IOSE80- hTERT (hTERT, human telomerase reverse transcriptase) cells not expressing exogenous AKT or ACTN4 IFP fusion proteins (Fig. 4A), an siRNA pool targeting ACTN4 induced a concordant reduction in ACTN4 protein expression and AKT phosphorylation. Strikingly, ACTN4 silencing increased levels of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 protein (Fig. 4A), a known downstream target of AKT (33). Additional siRNA constructs inhibited AKT phosphorylation, with ACTN4 knockdown and pAKT phosphorylation being concordant (Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Insulin induced translocation of AKT1 fused to a full-length GFP protein (in parental HeLa cells not expressing AKT or ACTN4 fusion proteins) to the cell membrane, which was blocked by ACTN4 siRNA knockdown, confirming a role for ACTN4 in the translocation of AKT1 to the membrane (Fig. 4B). The effects of ACTN4 knockdown on the phosphorylation of HA-AKT1 were bypassed by membrane-targeted myristylated AKT1 (Fig. 4C), indicating that ACTN4 knockdown prevents translocation of AKT1 to the cell membrane. ACTN4 knockdown did not markedly alter F-actin in HeLa cells, suggesting that the effects of ACTN4 siRNA were not secondary to the disruption of the cellular cytoskeleton (Fig. 4D). Finally, knockdown of ACTN4 significantly inhibited HeLa cell proliferation (Fig. 4E), with different siRNAs demonstrating similar activity on ACTN4 knockdown, decrease in AKT phosphorylation (Fig. 6), and cell proliferation. Thus, ACTN4 plays an essential role in AKT translocation, activation, signaling, and function, which demonstrates the ability of RePCA to uncover functional protein–protein interactions.

Fig. 4.

siRNA-mediated ACTN4 silencing alters AKT signaling and cell proliferation. (A) The effects of ACTN4 siRNA knockdown on AKT signaling. HeLa Tet-on and human ovarian surface epithelial cells IOSE80(hTERT) were transfected with ACTN4 siRNA or a nontargeting siRNA (NT-siRNA) pool (Dharmacon). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were serum-starved for 24 hr and stimulated with 5% FBS for 3 hr before lysis. Lysates (50 μg per lane) were resolved by 8% SDS/PAGE for the detection of ACTN4 and 12% for other proteins. β-actin immunoblotting showed equivalent loading and specificity of the siRNA. Scanning densitometric values of Western blots from three independent experiments in HeLa Tet-on cells (mean ± SE) were obtained with NIH IMAGE 1.63.1 software and are presented as densitometric values of target siRNA divided by control (nontargeting siRNA). (B) ACTN4 silencing blocks insulin-induced AKT1 translocation to HeLa cell membranes. HeLa cells were stably transfected to express AKT1-GFP. After serum starvation for 18 hr, insulin stimulation (20 μg/ml) for 10 min induced translocation of AKT1-GFP to the cell membrane in >90% of AKT1-GFP HeLa cells in the presence or absence of nontargeting siRNA. In contrast, <5% of cells transfected with ACTN4 siRNA demonstrated insulin-induced translocation of AKT1-GFP to the cell membrane. At least 100 cells were examined from different fields for each sample. (C) Inhibition of AKT1 phosphorylation by ACTN4 siRNA is bypassed by myristylated AKT1. HeLa cells were transfected with a nontargeting siRNA or ACTN4 siRNA pool. After 24 hr, the cells were transfected to express Myr-HA-AKT1 or HA-AKT1. Forty-eight hours after siRNA transfection, cells were serum-starved for 24 hr and stimulated with 10% FBS and 75 ng/ml IGF-1 for 10 min before lysis. pAKT1 (473) levels are presented as values relative to nontargeting siRNA. (D) ACTN4 knockdown does not alter the actin cytoskeleton. HeLa cells were transfected with nontargeting siRNA or ACTN4 siRNA. Actin cytoskeleton was stained with tetramethylrhodamine B isothiocyanate-labeled phalloidin 48 or 72 hr after transfection. Representing images are shown. (E) The effects of ACTN4 knockdown on cell proliferation. Proliferation of HeLa cells transfected with siRNA was assessed by 3,(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay kit (Sigma) 96 hr after transfection.

Discussion

The identification of known and likely AKT1-binding partners and substrates (Table 1) validated RePCA as being able to identify protein–protein interactions and potentially transient interactions between enzyme and substrate in mammalian cells. A previously uncharacterized physical and functional interaction was identified between ACTN4 and AKT1. Functional association was demonstrated by siRNA-mediated ACTN4 silencing, which inhibits AKT translocation and phosphorylation, resulting in up-regulation of p27Kip1 protein and a decrease in cell proliferation. An interaction between ACTN4 and AKT may underlie the pathophysiology of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, which is caused by ACTN4 mutations (34), suggesting novel therapeutic approaches. ACTN4 also associates with focal adhesions, tight junctions, and adherens junctions through interactions with the cytoskeleton and the tight-junction protein MAGI-1 (35), linking the PI3K/AKT pathway to motility and invasion.

RePCA has a number of potential advantages. (i) The ability to perform screens in a homologous mammalian cell environment allows native protein folding and posttranslational modifications. (ii) RePCA can be used to comparatively analyze multiple different cell lines or genetic backgrounds, avoiding the related bias and difficulties in generating cell-specific cDNA libraries. The host range of the retrovirus can be extended by pseudotyping with vesicular stomatitis virus G glycoprotein (36). (iii) RePCA can identify context-dependent interactions under different activation conditions or genetic manipulations or with specific drugs. (iv) The derivation of the ERM vector from Moloney murine leukemia virus (12) results in preferential integration near the start of transcriptional units, generating a high frequency of full-length or near-full-length fusion transcripts. Furthermore, because the ERM vector uses native splicing machinery, the approach can identify splicing-specific interactions and the identification of binding partners is not limited by size. (v) The Tet-responsive promoter allows high-level expression of endogenous targets during screening followed by repression of potentially toxic endogenous targets. Regulated expression of the endogenous target by doxycycline also limits false-positive interactions. (vi) The lack of background fluorescence combined with the high level of fluorescence when the PCA fragments are brought into proximity by interacting proteins makes the approach applicable to high-throughput screening. (vii) The resulting clones provide reagents for studies of the function and localization of protein complexes, suggesting potential functional consequences of the interactions. These clones can also be used in high-content drug, genomic, or chemical genomic screens aimed at preventing the formation of complexes or blocking the translocation of the complex to particular subcellular compartments. (viii) The reconstituted barrel structure of GFP and, by analogy, IFP is relatively stable (37). Thus, RePCA has the potential to stabilize or trap transient interactions, such as enzyme–substrate interactions, or to stabilize low-affinity interactions, allowing the identification of components of signaling pathways and networks not discoverable by other approaches. The relative ease and applicability of RePCA to high-throughput analysis allow sequential indentification of interacting partners and the creation of pathways and networks based on protein–protein interactions. (ix) RePCA can identify interactions in multiple different intracellular compartments, particularly cytoskeletal, membrane, and transcription-factor interactions, that are difficult to discover by using a Y2H or mass spectrometry approach. (x) Molecular interactions are detected directly, not through secondary events, such as transcription activation.

The RePCA approach has a number of potential limitations. (i) Intron-less genes cannot be captured by the ERM vector. Fortunately, these genes are relatively uncommon. (ii) The screen depends on a high-titer virus preparation for targeting a sufficient number of genes. (iii) Genes not accessible for viral integration will not be targeted. (iv) The fluorescent protein fragment may interfere with the formation of protein–protein interactions. (v) The fluorescent protein fragment may interfere with membrane insertion of type I integral membrane proteins or secreted proteins. (vi) The ability to trap enzyme substrate or weak interactions as well as other sources of binding may result in false-positive results. However, the use of both N- and C-terminal orientations for the bait as well as varying the length of linkers between the engineered GFP fragments and the bait/prey is likely to alleviate many of these concerns.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Plasmids.

HeLa Tet-on cells were from BD Clontech (Palo Alto, CA). 293T/17 was from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). TAg and human telomerase immortalized normal ovarian epithelial cells IOSE80(hTERT) (38) were from N. Auersperg (University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada). Plasmids VYF102 (IFPC vector), 11117-Y101 (expressing IFPN-AKT1), and 21622-Y108 (expressing PDK1-IFPC) were from Odyssey Thera, Inc. (San Ramon, CA) (11). Plasmid PS1941 encoding AKT1-GFP was from Bioimage (Soeborg, Denmark). Plasmids pcGP and pVSVG were from Xiao-Feng Qin (M. D. Anderson Cancer Center). ERM vectors are described in ref. 4. RePCA vectors for each of the three reading frames were constructed by inserting a PacI/AscI fragment containing the IFPC coding sequence into the ERM vectors digested with PacI/AscI (for details, see Supporting Materials and Methods). Full-length ACTN4 cDNA was from Origene Technologies, Inc. (Rockville, MD). The human AKT1 gene was cloned from OVCAR3 cells by RT-PCR. Construction of plasmids expressing IFPC-ACTN4wt, IFPC-ACTN4Δ310–665, IFPC-ACTN4Δ310–911, and Myr-HA-AKT1 are described in Supporting Materials and Methods.

RePCA Screen Procedure.

HeLa Tet-on cells were stably transfected with plasmid 11117-Y101 to express IFPN-AKT1. IFPN-AKT1 HeLa Tet-on cells were infected in exponential growth phase. Preparation of RePCA retrovirus and infection are described in ref. 39, with additional details in Supporting Materials and Methods. Infected cells were selected with 0.5 μg/ml puromycin (BD Clontech) for 5 days. In the last 2 days of selection, 2 μg/ml of doxycycline (BD Clontech) was added to induce the expression of IFPC fusions from Tet-responsive promoters. Fluorescent cells were sorted individually into 96-well plates. Doxycycline was withdrawn during recovery to reduce the expression of proteins that could have adverse effects on cell survival and growth (for additional details, see Supporting Materials and Methods).

Identification of Target Genes.

Total RNA was extracted from expanded clones by using RNeasy Mini kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Reverse transcription was performed with a random primer RT-1 (5′-GCAAATACGACTCACTATAGGGATCCNNNN(GC)ACG-3′; n = AGCT) (4), or a PolyT primer RT-1T (5′-GCAAATACGACTCACTATAGGGATCCTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′) using a SuperScript III kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The 5′ end of the RT-1 primer contains the T7 primer sequence. The cDNA was PCR-amplified with a specific IFPC primer (IFPCR, 5′-ACTTCAAGATCCGCCACAACATCGAG-3′) and the T7 primer (T7-2, 5′-GCAAATACGACTCACTATAGGGATC-3′) by using AccuTaq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen). Gel-purified PCR products were directly sequenced, with the resulting sequences used to search GenBank human nonredundant and expressed-sequence-tag databases by using BLAST.

RNAi and Cell Growth Assay.

A pool of four siRNAs targeting human ACTN4 and a nontargeting siRNA pool were from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). Two single siRNAs targeting human ACTN4 were from Ambion (Austin, TX). RNAi silencing was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. The effects of siRNA knockdown on cell growth was assessed by a 3,(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay (40).

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- PCA

protein-fragment complementation assay

- RePCA

retrovirus-based PCA

- ERM

enhanced retroviral mutagen

- Y2H

yeast two-hybrid

- IFP

intensely fluorescent protein

- IFPN

N-terminal portion of IFP

- IFPC

C-terminal portion of IFP

- ACTN4

α-actinin 4

- PDK1

phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase

- Co-IP

coimmunoprecipitation

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Fields S, Song O. Nature. 1989;340:245–246. doi: 10.1038/340245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin D, Tabb DL, Yates JR., III Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1646:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s1570-9639(02)00546-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turk BE, Cantley LC. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:84–90. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(02)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu D, Yang X, Yang D, Songyang Z. Oncogene. 2000;19:5964–5972. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnsson N, Varshavsky A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10340–10344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghosh I, Hamilton AD, Regan L. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:5658–5659. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu CD, Chinenov Y, Kerppola TK. Mol Cell. 2002;9:789–798. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00496-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michnick SW, Remy I, Campbell-Valois FX, Vallee-Belisle A, Pelletier JN. Methods Enzymol. 2000;328:208–230. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)28399-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Remy I, Michnick SW. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1493–1504. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.4.1493-1504.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagai T, Ibata K, Park ES, Kubota M, Mikoshiba K, Miyawaki A. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:87–90. doi: 10.1038/nbt0102-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu H, West M, Keon BH, Bilter GK, Owens S, Lamerdin J, Westwick JK. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2003;1:811–822. doi: 10.1089/154065803772613444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu X, Li Y, Crise B, Burgess SM. Science. 2003;300:1749–1751. doi: 10.1126/science.1083413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cantley LC. Science. 2002;296:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brazil DP, Yang ZZ, Hemmings BA. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:233–242. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alessi DR, James SR, Downes CP, Holmes AB, Gaffney PR, Reese CB, Cohen P. Curr Biol. 1997;7:261–269. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andjelkovic M, Alessi DR, Meier R, Fernandez A, Lamb NJ, Frech M, Cron P, Cohen P, Lucocq JM, Hemmings BA. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31515–31524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson KE, Coadwell J, Stephens LR, Hawkins PT. Curr Biol. 1998;8:684–691. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70274-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Datta SR, Dudek H, Tao X, Masters S, Fu H, Gotoh Y, Greenberg ME. Cell. 1997;91:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka M, Konishi H, Touhara K, Sakane F, Hirata M, Ono Y, Kikkawa U. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;255:169–174. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salinas M, Wang J, Rosa de Sagarra M, Martin D, Rojo AI, Martin-Perez J, Ortiz de Montellano PR, Cuadrado A. FEBS Lett. 2004;578:90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sussman J, Stokoe D, Ossina N, Shtivelman E. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:1019–1030. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feral CC, Nishiya N, Fenczik CA, Stuhlmann H, Slepak M, Ginsberg MH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:355–360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404852102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu D, Thakore CU, Wescott GG, McCubrey JA, Terrian DM. Oncogene. 2004;23:8659–8672. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Slegtenhorst M, Nellist M, Nagelkerken B, Cheadle J, Snell R, van den Ouweland A, Reuser A, Sampson J, Halley D, van der Sluijs P. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1053–1057. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.6.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamb RF, Roy C, Diefenbach TJ, Vinters HV, Johnson MW, Jay DG, Hall A. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:281–287. doi: 10.1038/35010550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dan HC, Sun M, Yang L, Feldman RI, Sui XM, Ou CC, Nellist M, Yeung RS, Halley DJ, Nicosia SV, Pledger WJ, Cheng JQ. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35364–35370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205838200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fukami K, Furuhashi K, Inagaki M, Endo T, Hatano S, Takenawa T. Nature. 1992;359:150–152. doi: 10.1038/359150a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shibasaki F, Fukami K, Fukui Y, Takenawa T. Biochem J. 1994;302:551–557. doi: 10.1042/bj3020551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Honda K, Yamada T, Endo R, Ino Y, Gotoh M, Tsuda H, Yamada Y, Chiba H, Hirohashi S. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1383–1393. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.6.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menez J, Le Maux Chansac B, Dorothee G, Vergnon I, Jalil A, Carlier MF, Chouaib S, Mami-Chouaib F. Oncogene. 2004;23:2630–2639. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Honda K, Yamada T, Hayashida Y, Idogawa M, Sato S, Hasegawa F, Ino Y, Ono M, Hirohashi S. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:51–62. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stephens L, Anderson K, Stokoe D, Erdjument-Bromage H, Painter GF, Holmes AB, Gaffney PR, Reese CB, McCormick F, Tempst P, et al. Science. 1998;279:710–714. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5351.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang J, Slingerland JM. Cell Cycle. 2003;2:339–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaplan JM, Kim SH, North KN, Rennke H, Correia LA, Tong HQ, Mathis BJ, Rodriguez-Perez JC, Allen PG, Beggs AH, Pollak MR. Nat Genet. 2000;24:251–256. doi: 10.1038/73456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patrie KM, Drescher AJ, Welihinda A, Mundel P, Margolis B. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30183–30190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203072200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burns JC, Friedmann T, Driever W, Burrascano M, Yee JK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8033–8037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Magliery TJ, Wilson CG, Pan W, Mishler D, Ghosh I, Hamilton AD, Regan L. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:146–157. doi: 10.1021/ja046699g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Auersperg N, Maines-Bandiera SL, Dyck HG, Kruk PA. Lab Invest. 1994;71:510–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soneoka Y, Cannon PM, Ramsdale EE, Griffiths JC, Romano G, Kingsman SM, Kingsman AJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:628–633. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.4.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hansen MB, Nielsen SE, Berg K. J Immunol Methods. 1989;119:203–210. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.