Abstract

Polynucleotide phosphorylase (PNPase) is an exoribonuclease and poly(A) polymerase postulated to function in the cytosol and mitochondrial matrix. Prior overexpression studies resulted in PNPase localization to both the cytosol and mitochondria, concurrent with cytosolic RNA degradation and pleiotropic cellular effects, including growth inhibition and apoptosis, that may not reflect a physiologic role for endogenous PNPase. We therefore conducted a mechanistic study of PNPase biogenesis in the mitochondrion. Interestingly, PNPase is localized to the intermembrane space by a novel import pathway. PNPase has a typical N-terminal targeting sequence that is cleaved by the matrix processing peptidase when PNPase engaged the TIM23 translocon at the inner membrane. The i-AAA protease Yme1 mediated translocation of PNPase into the intermembrane space but did not degrade PNPase. In a yeast strain deleted for Yme1 and expressing PNPase, nonimported PNPase accumulated in the cytosol, confirming an in vivo role for Yme1 in PNPase maturation. PNPase localization to the mitochondrial intermembrane space suggests a unique role distinct from its highly conserved function in RNA processing in chloroplasts and bacteria. Furthermore, Yme1 has a new function in protein translocation, indicating that the intermembrane space harbors diverse pathways for protein translocation.

Polynucleotide phosphorylases (PNPases) encompass an evolutionarily conserved enzyme family whose members regulate RNA levels in bacteria and plants. In Escherichia coli, PNPase associates with an RNA helicase and enolase in a degradosome complex, where it functions as both an exonuclease and a poly(A) polymerase to control RNA stability (32). In plants, PNPase localizes to the chloroplast stroma, where it performs polyadenylation and exonucleolytic degradation to mediate RNA turnover (3, 28, 29, 53). In both bacteria and plants, poly(A) addition to RNA constitutes a signal for PNPase-mediated RNA degradation.

Interestingly, PNPase is absent from archaea and single-cell eukaryotes including Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, and Plasmodium falciparum but is present in animals including the worm, fly, mouse, and human (24). This odd phylogenetic distribution suggests that PNPase might possess a unique function in animals, rather than its evolutionarily conserved role in the degradosome, as shown for prokaryotes and chloroplasts.

Recently, human PNPase was identified as an up-regulated gene in terminally differentiated melanoma cells and in senescent progeroid fibroblasts, implying a potential role in growth inhibition (25). Human PNPase is a 85-kDa nucleus-encoded protein that localizes to the mitochondrion (4, 38) and functions in vitro as a phosphate-dependent exoribonuclease (8, 26) and poly(A) polymerase (33). Analogous to bacterial and chloroplastic PNPase, mammalian PNPase could be expected to regulate RNA levels in the mitochondrial matrix. However, robust PNPase overexpression inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis with down-regulation of MYC and BCL-xL expression (42), suggesting that PNPase may degrade mRNAs in the cytosol. These observations deviate from a predicted role for PNPase in regulating mitochondrial RNA levels (33). A possible explanation for this disparity includes aberrant targeting of exogenous PNPase to the cytosol. Alternatively, PNPase might function within and outside mitochondria, akin to cytochrome c, apoptosis-inducing factor, Smac/DIABLO, HtrA2/Omi, Bit1, and endonuclease G, with the intermembrane space providing a location for mitochondrial activity and conditions that cause outer membrane permeability enabling cytosolic access (41). Indeed, we have identified PNPase by its interaction with the cytosolic TCL1 oncoprotein in recent work (8). Furthermore, our accompanying paper shows that PNPase does not regulate mitochondrial RNA levels but, after treatment with apoptotic stimuli, is mobilized late after cytochrome c release (4).

Given that the specific localization of PNPase is not understood, we have characterized the PNPase biogenesis pathway in detail. Our accompanying study shows that endogenous PNPase resides in the intermembrane space in mouse liver mitochondria and, when heterologously expressed in S. cerevisiae, localizes in mitochondria and not the cytosol (4). Moreover, PNPase has a typical N-terminal targeting sequence that confers mitochondrial localization.

Mitochondria possess an elaborate set of translocons on the outer membrane (TOM) and translocons on the inner membrane (TIM) to mediate the import and assembly of nucleus-coded proteins such as PNPase (20, 21, 36, 46). Whereas the TIM22 complex mediates the import of inner membrane proteins, including the carrier family and the import component Tim22, the TIM23 translocon imports proteins with a typical N-terminal targeting sequence (21). After passing through the TOM, the precursor engages the TIM23 complex; translocation initiation into the TIM23 complex requires the electrochemical membrane potential (Δψ) of the inner membrane. For proteins targeted to the matrix, the Hsp70 motor mediates translocation. The matrix processing protease (MPP), consisting of the heterodimer Mas1/Mas2, typically mediates cleavage of the presequence (9). Precursors destined for the intermembrane space, such as cytochromes b2 and c1, contain a bipartite targeting sequence. The N terminus directs the precursor to TIM23. After cleavage by the MPP, the precursor arrests at the “stop-transfer” domain in the translocon (12). The inner membrane protease (IMP), consisting of the complex Imp1/Imp2 and facing the intermembrane space, mediates a second cleavage, thereby trapping cytochrome b2 in the intermembrane space (9).

Additional proteases in the mitochondrial inner membrane have been implicated in import pathways in recent studies (2, 47). Beyond their role in protein degradation, the m-AAA (ATPases associated with a number of diverse cellular activities) proteases Yta10 and Yta12 are required for maturation of the ribosomal protein MrpL32 and cytochrome c peroxidase (Ccp1) (7, 34). The evolutionarily conserved rhomboid protease processes the substrates Mgm1, involved in mitochondrial dynamics, and Ccp1 (7, 16). These recent studies confirm that the mitochondrial proteolytic system is crucial for the maturation and assembly of precursors in the mitochondrion.

Import mechanisms into the intermembrane space are diverse (17). Translocation of proteins such as cytochromes b2 and c1 requires the hydrolysis of matrix ATP and Δψ. For proteins that lack a typical N-terminal targeting sequence and do not require a Δψ for translocation (thereby bypassing the TIM), import mechanisms rely on (i) the energy gain of protein folding, often around a cofactor, or (ii) the association of a protein with a high-affinity binding site, such as another protein.

Here we use the conserved import machinery of S. cerevisiae to investigate the pathway by which PNPase is localized to the intermembrane space. Import depends on the presence of Δψ, and the presequence is cleaved by MPP. Translocation of PNPase into the intermembrane space requires the i-AAA protease Yme1, which possesses chaperone-like activity (23); this constitutes the first evidence of a translocation function for this protease, presenting a new twist on biogenesis mechanisms in the intermembrane space. Conceivably, other intermembrane space proteins, particularly those involved in the execution events of apoptosis, may also utilize Yme1 for import.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and strains.

Standard genetics techniques were used for growth, manipulation, and transformation of yeast strains (14). Human PNPase cDNA was cloned by PCR from a Nalm-6 B-cell cDNA library with 5′-ccggtattatccATGGCGGCCTGCAGGTAC-3′ and 5′-ccgcacgtcgacTCACTGAGAATTAGATG-3′ primers (lowercase indicates inserted restriction site). PNPase was subcloned into pSP65 (Promega) and pcDNA3.1myc-His (Invitrogen) for in vitro transcription/translation. For expression in yeast, PNPase was subcloned into pYEX-BX (2μm, URA3; Clontech), and induction was regulated by the copper-inducible CUP1 promoter. The pYEX-BX-PNPase construct was transformed into GA74-1A or the corresponding mutant yeast strains (22). The Δyme1 strains were purchased from ResGen. The yeast strains MY111-2 (as the mas1 strain is designated) and JN174 (as the Δimp1 Δimp2 strain is designated) have been previously described (35, 51). The yme1E541Q strain was generously provided by Thomas Langer (23). The yeast strain deleted for tim54 (the Δtim54 strain) has been previously described (D. Hwang et al., submitted for publication). The E. coli strain for expressing His-tagged MPP was a gift from Vincent Geli (30). His-tagged Omi/HtrA2-(134-458) was generously provided by Antonis Zervos (5).

The PNPase-dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) fusion construct was generated by subcloning the first 157 amino acids of PNPase in frame with DHFR-His6 derived from pQE16 (QIAGEN) into pET28a (Novagen). Recombinant PNPase-DHFR was induced according to the manufacturer's protocols, and the recombinant protein was purified under denaturing conditions according to the manufacturer's protocols. For in vitro transcription/translation, PNPase-DHFR and PNPase(1-392) were amplified by PCR with 5′-ggggatttaggtgacactatagaaggagctaagcttATGGCGGCCTGCAGGTA-3′ (encoding the SP6 promoter at the 5′ end) and 5′-AAGCTTAGTGATGGTGATGG-3′ (PNPase-DHFR) or 5′-CTGTGTTTGTCCTCTTTGA-3′ [PNPase(1-392)] and isolated using a Nucleospin extraction kit (Clontech).

Purification of MPP and Omi/HtrA2 from E. coli and in vitro processing assay.

MPP and Omi/HtrA2 were purified as described previously (5, 30). Radiolabeled precursors (5 μl) or purified PNPase(1-157)-DHFR (2.5 μg) was incubated in a final volume of 20 μl or 165 μl cleavage buffer (50 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES-KOH [pH 7.4], 1 mM ZnCl2), respectively, in the presence or absence of MPP for 30 min at 30°C. The Omi protease cleavage reactions were performed as described above, except in 200 mM NaCl, 20 mM NaPO4 (pH 7.4), 5% glycerol at 37°C. Twenty micrograms of casein was used as a control substrate for Omi cleavage, and the inhibitor UCF-101 (Calbiochem) was used at a final concentration of 20 μM. Samples were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and autoradiography (radiolabeled precursors), immunoblotting with anti-DHFR (recombinant PNPase-DHFR), or Coomassie staining (casein). For Edman degradation, the cleaved PNPase DHFR was transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane for analysis. N-terminal sequencing was performed on an Applied Biosystems model 494 precise protein sequencer by the DNA core facility at the USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Import of radiolabeled proteins into isolated mitochondria, manipulation of mitochondria, and cross-linking studies.

Mitochondria were purified from yeast cells grown in rich ethanol/-glycerol medium (13) and assayed for in vitro protein import as described previously (39). Proteins were synthesized in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate in the presence of [35S]methionine after in vitro transcription of their corresponding genes by SP6 or T7 polymerase. The reticulocyte lysate containing the radiolabeled precursor was incubated with isolated mitochondria at 25°C in import buffer (1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 0.6 M sorbitol, 150 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM EDTA, 2 mM ATP, 2 mM NADH, 20 mM HEPESKOH [pH 7.4], 2 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM l-methionine). Where indicated, the potential across the mitochondrial inner membrane was dissipated with 1 μM valinomycin and 25 μM carbonyl cyanide p-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP). Nonimported radiolabeled proteins were removed by treatment with 100 μg/ml trypsin for 30 min on ice, and trypsin was inhibited with 200 μg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor. Osmotic shock experiments and cross-linking studies were performed as previously described (22, 27). After import, mitochondria were washed, suspended at 1 mg/ml in import buffer without bovine serum albumin and methionine, and incubated with 1 mM dithiobis(succinimidyl propionate) on ice for 30 min followed by a quench with 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. For immunoprecipitation, solubilized mitochondria were incubated with the corresponding monospecific rabbit immunoglobulin Gs coupled to protein A-Sepharose (39).

Miscellaneous.

Mitochondrial proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and a Tricine-based running buffer (43). Proteins were detected by immunoblotting using nitrocellulose and PVDF membranes and by visualization of immune complexes by use of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce). PNPase (1:1,000), AAC (1:5,000), cytochrome b2 (1:2,000), DHFR (1:2,000), and Mge1 (1:1,000) antisera were used in immunoblot analyses. For autoradiography, 6 or 8% gels were used for PNPase and 10 or 12% gels were used for PNPase-DHFR. Degradation assays for PNPase-DHFR and the model substrate Yta10-DHFR were performed as described previously (23).

RESULTS

PNPase requires the mitochondrial proteases for maturation.

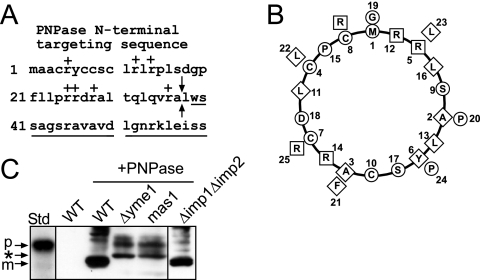

The N-terminal 37 amino acids are predicted to target PNPase to the mitochondrion (Fig. 1A), and this targeting sequence is absent from prokaryotic PNPase proteins (24). PNPase features a typical N-terminal targeting sequence in which the basic residues cluster on one face of the predicted α-helix and the hydrophobic residues cluster to other regions (Fig. 1B) (48). As we show in the accompanying paper, PNPase resides in the intermembrane space (4); however, to specifically localize PNPase to this compartment, we investigated the PNPase biogenesis pathway in detail. Because PNPase is processed at the N terminus (4), we first determined which mitochondrial proteases are required. We took advantage of yeast for in vivo studies and yeast mitochondria for in organello studies, as protein import is highly conserved between animals and fungi (18, 21), and yeast are amenable to genetic and biochemical manipulations. Specifically, heterologous PNPase expressed in yeast and endogenous PNPase from mouse liver fractionated identically in isolated mitochondria, displayed similar sensitivities to protease treatment during osmotic shock, and assembled in similarly sized complexes (4).

FIG. 1.

PNPase processing is inhibited in yeast lacking the MPP and i-AAA protease Yme1. (A) Schematic showing the N-terminal targeting sequence within the N terminus of PNPase. The basic residues are indicated with a “+,” the sequence of the mature PNPase is underlined, and the arrows mark the MPP cleavage site. (B) The first 26 amino acids were placed on a helical wheel (40). The boxes mark basic residues, the diamonds mark hydrophobic residues, and the circles mark the remaining residues. (C) PNPase was expressed heterologously in yeast under control of the Cu2+-inducible CUP1 promoter. Expression was analyzed in a total lysate by immunoblotting with polyclonal anti-PNPase antibody. PNPase was expressed (+PNPase) in strains defective in MPP (mas1), IMP (Δimp1Δimp2), and Yme1 (Δyme1) and in the WT strain. The precursor form (p) is marked for the in vitro-translated standard (Std), and the mature form (m) is marked for PNPase expressed in WT yeast (WT +PNPase). The asterisk marks products that accumulate when PNPase import and assembly are impaired.

We expressed PNPase under control of the Cu2+-inducible CUP1 promoter (31) and analyzed expression in strains that contained mutations in the known mitochondrial proteases (Fig. 1C) (7, 51). The MPP cleaves the targeting sequence of TIM23 substrates as the N-terminal targeting sequence enters the matrix (9). As MPP is essential for viability, we utilized the temperature-sensitive mas1 mutant to assess PNPase maturation (51). We also anticipated that PNPase would be cleaved by a protease in the intermembrane space due to its intermembrane space localization; likely candidates included the IMP (Δimp1 Δimp2 strain) and the i-AAA protease Yme1 (Δyme1 strain) (9). Total protein lysates from cells expressing PNPase were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with PNPase antiserum. The mature form of PNPase was observed in wild-type (WT) yeast cells, as previously shown (4), and in cells lacking the IMP, which migrates faster in the gel than the control in vitro translation of the PNPase precursor (Fig. 1C). However, mature PNPase was not observed in cells defective in the MPP and the Yme1 protease. Aberrantly sized bands were detected when PNPase import was defective; these most likely correspond to degradation products that accumulate because PNPase import and processing are impaired.

MPP mediates cleavage of PNPase.

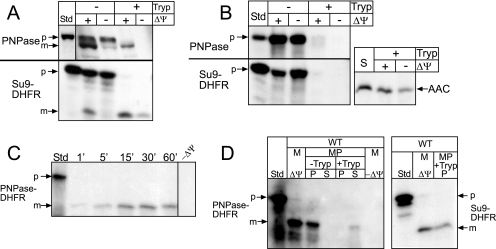

Using the in organello import assay (12, 51), we imported radiolabeled PNPase into WT mitochondria (Fig. 2A) (4). As a control, we included the matrix-targeted fusion protein Su9-DHFR, which consists of subunit 9 of the Neurospora crassa ATPase fused to the reporter dihydrofolate reductase (37). The import assay was performed for 10 min at 25°C in the presence and absence of Δψ; import was confirmed by removing nonimported precursor with trypsin treatment. As expected, PNPase translocated into isolated WT mitochondria, and the N-terminal sequence was processed (Fig. 2A). We used the same assay to investigate import of radiolabeled PNPase and Su9-DHFR into mas1 mitochondria, which are defective in MPP (Fig. 2B) (12, 51). In a control reaction, we included the TIM22 substrate, the ADP/ATP carrier (AAC), which is targeted to the inner membrane via the TIM22 translocon (22). Mitochondria from the temperature-sensitive mas1 strain were prepared after being shifted to the restrictive temperature for 6 h as reported previously (51). The mature form of Su9-DHFR did not accumulate in the presence of a Δψ in the mas1 mitochondria (12); further, AAC was imported into the inner membrane, indicating that the TIM22 import pathway functions in the mas1 mitochondria. PNPase import and processing failed in mas1 mitochondria irrespective of Δψ, confirming the in vivo results from Fig. 1C.

FIG. 2.

MPP mediates cleavage of PNPase. (A) Radiolabeled PNPase was synthesized in vitro and incubated with isolated WT mitochondria in the presence or absence of a Δψ at 25°C for 10 min. After import, samples were divided in equal aliquots for protease treatment with trypsin (Tryp) to remove nonimported precursor; protease activity was halted with soybean trypsin inhibitor. As a control, matrix-localized Su9-DHFR was also imported. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and fluorography. Standard (Std) refers to 10% of the radioactive precursor added to each assay. p, precursor; m, mature. (B) Import of PNPase and Su9-DHFR was performed as described for panel A into mas1 mitochondria. The inner membrane marker ADP/ATP carrier (AAC) was imported as a control; import reactions with AAC, which lacks a cleavable targeting sequence, were treated with protease followed by carbonate extraction to confirm insertion into the inner membrane. (C) Radiolabeled PNPase-DHFR (the N-terminal 157 amino acids of PNPase fused to DHFR) was imported into isolated WT mitochondria, and aliquots were removed at the designated time points. Nonimported precursor was removed with protease treatment. Standard (Std) represents 10% of the radioactive precursor in each time point. (D) PNPase-DHFR was imported into WT mitochondria (M) at 25°C for 10 min in the presence and absence of Δψ. Samples were incubated in hypotonic buffer to swell the outer membrane, generating mitoplasts (MP), in the presence and absence of trypsin (Tryp), followed by inactivation with trypsin inhibitor. Mitoplasts were recovered by centrifugation (P) and separated from the supernatant (S) containing the soluble intermembrane space contents. As a control, Su9-DHFR was imported and treated identically; relevant reactions representing import in the presence of Δψ and the recovered mitoplast fraction (P) treated with trypsin (+Tryp) are shown.

To validate that MPP is required for the putative first cleavage step and that the N terminus of PNPase indeed functions as a targeting sequence, we fused PNPase amino acids 1 to 157 to DHFR, generating the chimeric construct PNPase-DHFR. This radiolabeled fusion protein was incubated with WT mitochondria, and aliquots were removed during a time course and treated with protease to remove nonimported precursor (Fig. 2C). As shown for native PNPase, the fusion protein was imported into isolated mitochondria. To confirm that the first 157 amino acids were sufficient to localize PNPase to the intermembrane space, we coupled the import assay with hypotonic lysis treatment (Fig. 2D, left panel); the mitochondria were diluted into buffer with a final sorbitol concentration of 0.06 M, which selectively ruptures the outer membrane but leaves the inner membrane intact, to generate mitoplasts (12). After osmotic shock, the PNPase-DHFR was not soluble but remained associated with the membranes, as has been shown for endogenous PNPase (4). However, trypsin treatment degraded the imported PNPase-DHFR, indicating that the PNPase-DHFR was localized to the intermembrane space. As a matrix-targeted control, imported Su9-DHFR remained protected from protease (Fig. 2D, right panel; note that only relative lanes for the control have been shown). Therefore, the first 157 amino acids contain the necessary targeting information to direct PNPase to the intermembrane space.

To test the requirement for MPP, mitochondria were incubated with MPP inhibitors, EDTA and 1,10-o-phenanthroline, prior to import of PNPase, Su9-DHFR, and AAC (Fig. 3A) (52). Mitochondria treated with the chelators lacked processed PNPase and Su9-DHFR; AAC was imported into the inner membrane, confirming that the chelator treatment did not inhibit the TIM22 import pathway and that the mitochondria were still functional (6). We then purified recombinant MPP containing a hexahistidine tag for an in vitro cleavage assay (Fig. 3B) (11). Recombinant MPP was eluted from the Ni2+-agarose and incubated with in vitro-translated substrates. Purified MPP cleaved radiolabeled PNPase and Su9-DHFR (Fig. 3C). In addition, MPP mediated the first cleavage of cytochrome c1 to the intermediate form. The purified MPP was used in a dilution assay to compare the cleavage efficiencies of PNPase, PNPase-DHFR, and Su9-DHFR (Fig. 3D). The Su9 targeting sequence is a unique substrate for the MPP because it contains two cleavage sites (44), both of which are cleaved very efficiently. MPP at a 1:10 dilution cleaved approximately 50% of the PNPase constructs and Su9-DHFR. Therefore, the MPP cleavage efficiencies for PNPase and PNPase-DHFR were similar to that for the control substrate, and MPP cleaved PNPase at one location.

FIG. 3.

Recombinant MPP mediates cleavage of PNPase. (A) WT mitochondria were left untreated or were incubated in 10 mM EDTA, 2 mM o-phenanthroline (o-phe) for 15 min prior to the start of the import reaction to inhibit the endogenous MPP (52). Radiolabeled PNPase, Su9-DHFR, and AAC were imported as described for Fig. 2A. Nonimported AAC was removed by protease treatment, but protease addition was omitted for Su9-DHFR and PNPase. Standard (S) refers to 10% of the radioactive precursor added to each assay. p, precursor; m, mature. (B) Recombinant MPP (10) was purified over a Ni2+ column from a total lysate (T), followed by washing to remove unbound proteins. Purified MPP was eluted in fractions 2 and 3 in the presence of 300 mM imidazole. (C) In an in vitro cleavage assay (10), MPP was incubated with radiolabeled PNPase, Su9-DHFR, and cytochrome c1. The standard (Std) is an equal volume of the radioactive precursor. i, intermediate. (D) Serial MPP dilutions were incubated with PNPase, PNPase-DHFR, and Su9-DHFR for 30 min at 30°C. The reactions were stopped with SDS sample buffer. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected by fluorography. (E) Recombinant PNPase-DHFR was purified using a C-terminal hexahistidine tag for an in vitro cleavage assay, and cleavage was confirmed by immunoblot analysis with a polyclonal antibody against DHFR (αDHFR). The cleaved DHFR was recovered for analysis by Edman degradation.

Endogenous and heterologously expressed PNPase sequences have identical N termini.

To compare the biogenesis of PNPase in yeast with that in mammals, we identified the N terminus of PNPase in mammalian cells by use of mass spectrometry (Fig. 1A) (4). PNPase was purified from mammalian cells by coimmunoprecipitation with TCL1 (8) and analyzed by mass spectrometry. The tandem mass spectrometry spectra showed three peptide fragments with a nontryptic amino terminus for 38-LWSSAGSR-45 that marked the 5′ boundary of recovered PNPase sequences; peptide spectra were not detected amino terminal to this position. Tandem mass spectrometry coverage was excellent, at ∼85% of the full-length protein, including the missing N-terminal 37 residues.

We purified recombinant PNPase-DHFR for N-terminal sequencing using Edman degradation. PNPase-DHFR was cleaved after the addition of yeast MPP (Fig. 3E), and the cleaved DHFR fragment was recovered after transfer to a PVDF membrane. From the Edman sequencing assay, leucine-38 was also identified as the N-terminal amino acid, as indicated in Fig. 1A. These results indicate that the N terminus of PNPase is identical whether cleaved with recombinant yeast MPP or isolated from mammalian cells. Additionally, the cleavage site resides at a consensus R−2 site for MPP, in which an arginine residue is located at the −2 position from the cleavage point (Fig. 1A) (49). Thus, PNPase processing in yeast mitochondria is identical to that in mammalian mitochondria, confirming yeast as a valid model for mitochondrial import studies of mammalian proteins. Further, MPP is the sole protease required for PNPase processing.

Yme1 is required for PNPase import.

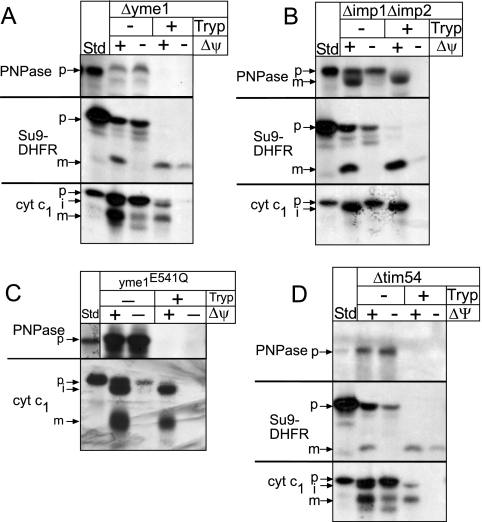

Given the necessity of Yme1 for PNPase maturation in yeast mitochondria (Fig. 1C), we characterized the translocation pathway of PNPase into the intermembrane space. PNPase and controls Su9-DHFR and cytochrome c1 were imported into mitochondria lacking Yme1 (Δyme1 mitochondria) or IMP (Δimp1 Δimp2 mitochondria) (Fig. 4A and B). PNPase and Su9-DHFR imported efficiently into Δimp1 Δimp2 mitochondria; however, mature cytochrome c1 was not generated, as IMP is required for the second cleavage that occurs during cytochrome c1 import (12). Note that the intermediate form of cytochrome c1 is protected from added protease, indicating that the C terminus has completely crossed the outer membrane (50). In contrast to Su9-DHFR and cytochrome c1, which imported correctly, PNPase did not import into Δyme1 mitochondria. In addition, marker proteins were localized identically in WT and Δyme1 mitochondria (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), indicating that Δyme1 mitochondria were not generally defective in assembly. We analyzed whether PNPase import was dependent upon functional Yme1 by testing import into mutant yme1E541Q mitochondria, expressing a proteolytically inactive variant of Yme1 with a point mutation in the proteolytic site (23). As in the Δyme1 mitochondria, PNPase import was selectively inhibited (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Yme1 is required for PNPase assembly in the intermembrane space. Radiolabeled PNPase, Su9-DHFR, and cytochrome c1 were imported into Δyme1 (A), Δimp1 Δimp2 (B), yme1E514Q (Su9-DHFR control omitted) (C), or Δtim54 (D) mitochondria in the presence and absence of Δψ as described for Fig. 2A. In half of the samples, nonimported precursor was removed by trypsin treatment, and analysis was done subsequently with SDS-PAGE and fluorography. p, precursor; i, intermediate; m, mature.

Previously, we have shown that Tim54 is required for assembly of Yme1 into a proteolytically active complex (Hwang et al., submitted). To confirm that Yme1 is essential for PNPase biogenesis, we investigated import of PNPase and controls Su9-DHFR and cytochrome c1 into mitochondria deleted for TIM54 (Δtim54 mitochondria) (Fig. 4D). Whereas Su9-DHFR and cytochrome c1 were imported, PNPase import was impaired in Δtim54 mitochondria. This result verifies that the fully assembled and functional Yme1 complex is required for PNPase accumulation in the intermembrane space.

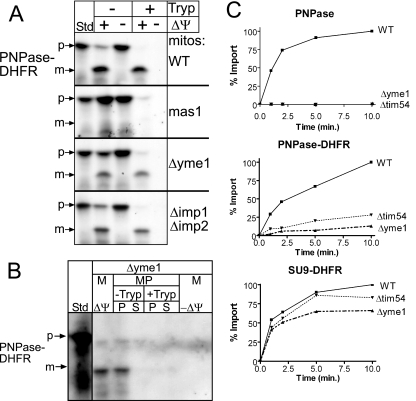

We next probed the events at the outer membrane in more detail. PNPase-DHFR import into WT, mas1, Δyme1, and Δimp1 Δimp2 mitochondria and subsequent protease treatment to remove nonimported precursor were performed (Fig. 5A). PNPase-DHFR import was inhibited in mas1 mitochondria but occurred normally in WT and Δimp1 Δimp2 mitochondria. Interestingly, PNPase-DHFR was imported into Δyme1 mitochondria, as PNPase-DHFR remained protected from added protease. As expected from the osmotic shock experiments illustrated in Fig. 2D, PNPase-DHFR localized to the intermembrane space in Δyme1 mitochondria because PNPase-DHFR was sensitive to exogenous protease introduced during osmotic shock (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Yme1 is required for efficient translocation of PNPase and PNPase-DHFR. (A) PNPase-DHFR was imported into WT, mas1, Δyme1, and Δimp1 Δimp2 mitochondria (mitos) as described for Fig. 2A. (B) As shown in Fig. 2D in the same set of experiments, imported PNPase-DHFR was localized to the intermembrane space after osmotic shock. (C) Time course assays were performed for the import of PNPase, PNPase-DHFR, and Su9-DHFR (control) into WT, Δyme1, and Δtim54 mitochondria at the indicated times. Nonimported precursor was removed by trypsin treatment, and equal aliquots were separated by SDS-PAGE. The percent substrate imported was quantitated from fluorographs by use of a scanning densitometer. The amount of precursor that imported into WT mitochondria at the end time point was set at 100%.

We performed time course assays and quantitated import for PNPase, PNPase-DHFR, and Su9-DHFR into WT, Δyme1, and Δtim54 mitochondria (Fig. 5C). Whereas the import of Su9-DHFR was efficient, PNPase import was essentially undetectable in mitochondria lacking functional Yme1. PNPase-DHFR import also required functional Yme1 for efficient import, because import was decreased by approximately 75 to 80% in Δtim54 and Δyme1 mitochondria. Given that PNPase-DHFR (∼40 kDa) is shorter than PNPase, we also tested the import of truncated PNPase(1-392) (∼43 kDa) into Δyme1 mitochondria in time course assays (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material); as with PNPase-DHFR, the import of truncated PNPase(1-392) was similarly decreased, suggesting that Yme1 facilitates translocation across the outer membrane. Taken together, these data show that Yme1 is required for the maturation of PNPase in the intermembrane space.

The PNPase translocation intermediate engages the TOM and TIM23 and binds to Yme1.

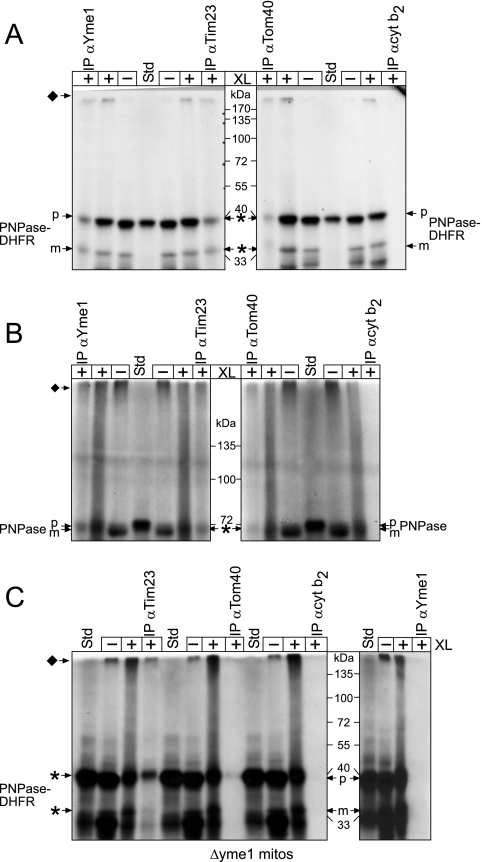

Based on our import analysis, we predicted that, during translocation, PNPase should engage the TOM and TIM23 and bind directly to Yme1. PNPase and PNPase-DHFR were imported into WT mitochondria followed by cross-linking with the thiol-cleavable cross-linker dithiobis(succinimidyl propionate) (Fig. 6A and B). After a quenching with 0.1 M Tris, an aliquot of the PNPase-DHFR was separated by SDS-PAGE in the absence of reductant, whereas the remainder was immunoprecipitated with antibodies against Tim23, Yme1, Tom40, and the negative control, cytochrome b2. Cross-linked PNPase migrated near the top of the gel; this large cross-linked product was expected because Yme1 assembles into a large homo-oligomeric complex (23) and our cross-linking conditions indicated that several Yme1 monomers were simultaneously cross-linked (data not shown). After the immunoprecipitation reaction, we cleaved the cross-linked products with the addition of β-mercaptoethanol to release cross-linked PNPase-DHFR to its native molecular mass and separated the products by SDS-PAGE. As predicted, PNPase and PNPase-DHFR bound directly to Yme1, Tom40, and Tim23 but not to cytochrome b2.

FIG. 6.

Yme1 binds directly to PNPase and mediates translocation into the intermembrane space. (A) PNPase-DHFR was imported into WT mitochondria for 10 min at 25°C (−XL) and an aliquot was removed. Proteins were cross-linked (+XL) by the addition of 1.0 mM dithiobis(succinimidyl propionate) for 30 min followed by quenching with 0.1 M Tris-HCl. After an aliquot was removed, mitochondria were subsequently solubilized followed by immunoprecipitation (IP) with antibodies (α) against Yme1, Tim23, Tom40, and the control cytochrome b2 (cyt b2) Because cross-linked PNPase-DHFR migrates at a high molecular mass (indicated by the diamond), the immunoprecipitated cross-linking reactions were released with β-mercaptoethanol addition in the sample buffer, whereas reductant was omitted from the cross-linking reactions. The asterisks indicate cross-linked PNPase-DHFR (released by treatment with reductant) that copurified with the target protein of the antibody. (B) Cross-linking and immunoprecipitation assays were performed with full-length PNPase as described for panel A. (C) Cross-linking and immunoprecipitation assays were performed with PNPase-DHFR import into Δyme1 mitochondria. Note that PNPase-DHFR was not immunoprecipitated with antibodies against Yme1, confirming the specificity of the Yme1-PNPase interaction.

As further confirmation, we investigated the association of PNPase-DHFR into yme1E541Q and Δyme1 mitochondria using the same cross-linking protocol (Fig. 6C) (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). PNPase-DHFR bound directly to Yme1, Tom40, and Tim23 in yme1E541Q mitochondria. As expected, a PNPase-DHFR-Yme1 interaction was not detected in mitochondria lacking Yme1 (Fig. 6C), although interactions with TIM23 and TOM were detected, indicating that the precursor can engage the translocons. Consequently, a new function has been determined for Yme1: translocation of precursors into the intermembrane space.

PNPase-DHFR is not a proteolytic substrate for Yme1.

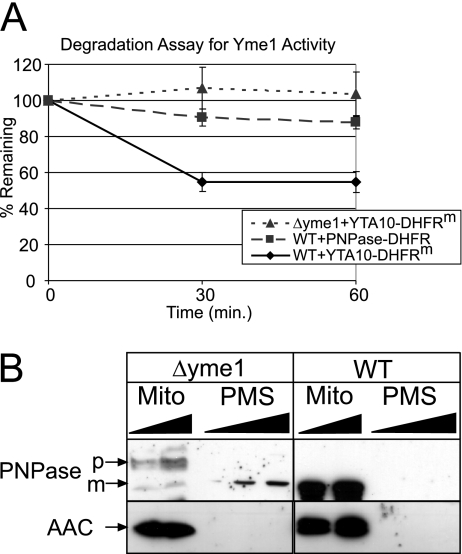

To determine if Yme1 might bind to PNPase-DHFR because Yme1 functions as a proteolytic component rather than as an import mediator, we compared PNPase-DHFR degradation with that of the Yme1p model substrate for degradation assays, Yta10-DHFRm (23), which consists of a fusion between the N-terminal 161 amino acids of Yta10p and a loosely folded mutant of DHFR. As described previously, PNPase-DHFR and Yta10-DHFRm constructs were imported into WT mitochondria for 30 min in the presence of an ATP-regenerating system at 37°C (23), and stability was then measured over a 60-min period (Fig. 7A). Whereas approximately 50% of the Yta10-DHFRm was degraded in WT mitochondria, PNPase-DHFR was stable in WT mitochondria, similar to the stability of Yta10-DHFRm in mitochondria deleted for yme1. If PNPase was indeed a proteolytic substrate for Yme1, mature PNPase would be expected to accumulate in mitochondria when expressed in the Δyme1 yeast strain. We examined the targeting and stability of PNPase in WT and Δyme1 mitochondria in vivo (Fig. 7B). With WT mitochondria, we found that both PNPase and the marker AAC localized to mitochondria. However, with Δyme1 mitochondria, we found that PNPase did not accumulate in the mitochondrion, supporting a role for Yme1 in the import of PNPase. We assign a new function to Yme1 in the translocation of PNPase (but interestingly not in proteolytic processing or degradation) and suggest that other proteins, particularly sequestered mammalian apoptotic proteins residing in the intermembrane space, may also rely on Yme1 for biogenesis.

FIG. 7.

PNPase is not a proteolytic substrate of Yme1. (A) Radiolabeled Yta10-DHFRm and PNPase-DHFR were imported into WT mitochondria for 30 min, and nonimported precursor was removed by protease treatment. The mitochondria were then incubated in the presence of an ATP-regenerating system at 37°C, and aliquots were removed at the indicated times to measure stability. The rate of proteolysis during the time course from three independent assays was quantitated using a Bio-Rad FX molecular imager and the affiliated Quantity 1 software. The amounts of Yta10-DHFRm and PNPase-DHFR remaining at each chase time point are expressed as the percentages of the amounts detected for the respective strains at t = 0 (set at 100%; mean ± standard deviation; n = 3). As a control for Yme1-dependent degradation of Yta10-DHFRm, a control reaction experiment was performed with Δyme1 mitochondria. (B) Mitochondria (Mito) and the postmitochondrial supernatant (PMS) were fractionated from Δyme1 and WT mitochondria expressing PNPase. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted for PNPase and the mitochondrial marker AAC.

DISCUSSION

PNPase is localized to the intermembrane space.

In contrast to studies that suggest a localization and function for PNPase in the cytosol or mitochondrial matrix (26, 33, 38), our accompanying study finds that PNPase is a new resident in the intermembrane space (4). Previous studies have suggested that PNPase functions in the cytosol to degrade specific cytosolic RNAs. However, these results may be artifact, because PNPase was expressed with an N-terminal tag that blocked translocation into the mitochondria and/or PNPase was overexpressed (25, 26). Indeed, in our companion work, we specifically show that an N-terminal tag appended to the N terminus blocked import and processing of PNPase (4). In another study, PNPase was not implicated in the regulation of RNA dynamics in the mitochondrial matrix (33). From our detailed analysis of PNPase biogenesis, we place PNPase precisely in the intermembrane space and define its specific function with respect to mitochondrial localization.

A new function for Yme1 in protein translocation.

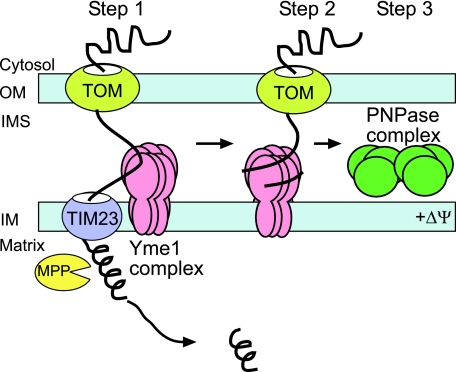

We have used a systematic approach, taking advantage of yeast and isolated mitochondrion mutants to directly investigate the biogenesis pathway of PNPase. Our studies reveal an unexpected twist on import mechanisms into the intermembrane space (Fig. 8). PNPase is imported via the TOM and TIM23. MPP mediates cleavage (step 1) and Yme1 serves as a nonconventional translocation motor to pull PNPase into the intermembrane space (step 2). PNPase then assembles in mature complexes similarly sized in both yeast and mammalian mitochondria (step 3) (4); this complex has been postulated to be a trimer or dimer of trimers, based on the structure of the bacterial PNPase (45).

FIG. 8.

Yme1 mediates PNPase import into the intermembrane space. The schematic shows the import pathway of PNPase. See Discussion for details. OM, outer membrane; IM, inner membrane; IMS, intermembrane space.

PNPase contains a typical N-terminal targeting sequence, and MPP processes PNPase at a predicted cleavage site. In addition, the region following the N-terminal targeting sequence (amino acids 45-AVAVDLG-51) is hydrophobic and may serve as a stop-transfer domain to arrest translocation in TIM23, similar to the stop-transfer domains in cytochromes b2 and c1 (12). The substrate NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase shows similar properties (15), requiring MPP cleavage for localization in the intermembrane space. However, NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase biogenesis is more complicated, since it resides in both the outer membrane and the intermembrane space and is dependent upon folding and interactions with the TOM and TIM23.

Given that cross-links between PNPase and Tom40, Tim23, and Yme1 can be trapped, Yme1 is seemingly in close proximity to TIM23. Surprisingly, a processed PNPase intermediate is not detected in mitochondria lacking Yme1; therefore, Yme1 may play an indirect role in mediating MPP cleavage, potentially by stabilizing PNPase in a conformation that is amenable for MPP cleavage in TIM23. Yme1 pulls the C terminus of PNPase across the TOM complex, as evidenced by defective full-length PNPase import in yme1 mutant mitochondria (Fig. 1C and 4A). The normal function assigned to Yme1 is that of a protease; however, PNPase-DHFR was not efficiently degraded by Yme1 in comparison to the model substrate Yta10-DHFRm.

Although other AAA protease family members have been implicated in translocation, this study uniquely assigns a translocation function to Yme1. Previously, Yme1 was characterized only for its chaperone and protease activities (2). However, Yme1's chaperone function in translocation is not unexpected, because these functions have been observed for the AAA proteases. Leonhard and colleagues have reported that Yme1 specifically senses the folding state of solvent-exposed domains and degrades nonnative membrane proteins (23), extracting them from the membrane. The recombinant AAA domain of Yme1 binds to unfolded peptides and suppresses their aggregation. Additionally, the m-AAA proteases Yta10 and Yta12, which face the matrix, mediate the assembly of cytochrome oxidase (1). Finally, the AAA protease Cdc48 is proposed to function in retrograde translocation, pulling a misfolded protein from the endoplasmic reticulum (19). Our studies demonstrate that Yme1 binds directly to unfolded PNPase during translocation, a feature reminiscent of chaperones, and then diverts it into the intermembrane space rather than targeting it for degradation. Plausibly, partner proteins may participate in this pathway, as has been reported for other AAA proteases. Future studies to elucidate the mechanism by which Yme1 targets PNPase for import rather than degradation will provide interesting insights into the function of this protease.

Since mammalian mitochondria contain the Omi protease, which is absent in yeast (41), we ruled out recombinant Omi protease as an import mediator of PNPase (5) (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). We have attempted to investigate the role of Yme1 in PNPase import in cultured mammalian cells by down-regulating Yme1 levels using RNA interference (4). Unfortunately, the cells died quickly, and unprocessed full-length PNPase was undetectable in isolated cytosol and mitochondrial fractions. Because of difficulties manipulating cultured mammalian cells, yeast mitochondria have proven advantageous, given the conservation of protein import pathways among plants, animals, and fungi.

What is the function of PNPase in the intermembrane space?

The detailed localization presented herein creates a framework for assigning a function to PNPase. Our accompanying paper shows that down-regulation of PNPase via RNA interference impacts mitochondrial morphology and respiration and that PNPase is mobilized late with apoptotic stimuli and may subsequently bind to TCL1 (4). That PNPase is found only in animals and not in fungi suggests it may have acquired a unique function distinct from its conserved role in RNA dynamics. Additional intermembrane space proteins, particularly those implicated in apoptosis, may require Yme1 for translocation. Given the recent unique discoveries in mitochondrial biology, PNPase may participate in a novel pathway in the intermembrane space, which may be reflected by the new import pathway reported here.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas Langer (University of Cologne) for providing the Yme1 point mutant strain and Antonis Zervos (University of Central Florida) for providing the Omi protease. We also thank members of the Koehler, Teitell, and van der Bliek labs for stimulating discussions.

This work was supported by NIH grants Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA HD041889 (R.N.R.), Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA GM07185 (J.D.G.), R01GM061721 and R01GM073981 (C.M.K.), and R01CA90571 and R01CA107300 (M.A.T.); by Muscular Dystrophy Association grant 022398 (C.M.K.); by American Heart Association grant 0640076N (C.M.K.); and by a grant from CMISE, a NASA URETI Institute, grant NCC 2-1364 (M.A.T.). C.M.K. is an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association, and M.A.T. is a Scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 September 2006.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arlt, H., R. Tauer, H. Feldmann, W. Neupert, and T. Langer. 1996. The YTA10-12 complex, an AAA protease with chaperone-like activity in the inner membrane of mitochondria. Cell 85:875-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold, I., and T. Langer. 2002. Membrane protein degradation by AAA proteases in mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1592:89-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baginsky, S., and W. Gruissem. 2002. Endonucleolytic activation directs dark-induced chloroplast mRNA degradation. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:4527-4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, H.-W., R. N. Rainey, C. E. Balatoni, D. W. Dawson, J. J. Troke, S. Wasiak, J. Hong, H. M. McBride, C. M. Koehler, M. A. Teitell, and S. W. French. 2006. Mammalian polynucleotide phosphorylase is an intermembrane space RNase that maintains mitochondrial homeostasis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:8475-8487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cilenti, L., Y. Lee, S. Hess, S. Srinivasula, K. M. Park, D. Junqueira, H. Davis, J. V. Bonventre, E. S. Alnemri, and A. S. Zervos. 2003. Characterization of a novel and specific inhibitor for the pro-apoptotic protease Omi/HtrA2. J. Biol. Chem. 278:11489-11494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curran, S. P., D. Leuenberger, E. Schmidt, and C. M. Koehler. 2002. The role of the Tim8p-Tim13p complex in a conserved import pathway for mitochondrial polytopic inner membrane proteins. J. Cell Biol. 158:1017-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esser, K., B. Tursun, M. Ingenhoven, G. Michaelis, and E. Pratje. 2002. A novel two-step mechanism for removal of a mitochondrial signal sequence involves the mAAA complex and the putative rhomboid protease Pcp1. J. Mol. Biol. 323:835-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.French, S. W., D. W. Dawson, H.-W. Chen, R. N. Rainey, S. A. Sievers, C. E. Balatoni, L. Wong, J. J. Troke, M. T. N. Nguyen, C. M. Koehler, and M. A. Teitell. 28 August 2006, posting date. The TCL1 oncoprotein binds the RNase PH domains of the PNPase exoribonuclease without affecting its RNA degrading activity. Cancer Lett. [Online.] doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.07.06. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Gakh, O., P. Cavadini, and G. Isaya. 2002. Mitochondrial processing peptidases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1592:63-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geli, V. 1993. Functional reconstitution in Escherichia coli of the yeast mitochondrial matrix peptidase from its two inactive subunits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:6247-6251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geli, V., M. J. Yang, K. Suda, A. Lustig, and G. Schatz. 1990. The MAS-encoded processing protease of yeast mitochondria. Overproduction and characterization of its two nonidentical subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 265:19216-19222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glick, B. S., A. Brandt, K. Cunningham, S. Muller, R. L. Hallberg, and G. Schatz. 1992. Cytochromes c1 and b2 are sorted to the intermembrane space of yeast mitochondria by a stop-transfer mechanism. Cell 69:809-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glick, B. S., and L. Pon. 1995. Isolation of highly purified mitochondria from S. cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 260:213-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guthrie, C., and G. R. Fink. 1991. Methods in enzymology, vol. 194. Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Calif. [PubMed]

- 15.Haucke, V., C. S. Ocana, A. Honlinger, K. Tokatlidis, N. Pfanner, and G. Schatz. 1997. Analysis of the sorting signals directing NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase to two locations within yeast mitochondria. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:4024-4032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herlan, M., F. Vogel, C. Bornhovd, W. Neupert, and A. S. Reichert. 2003. Processing of Mgm1 by the rhomboid-type protease Pcp1 is required for maintenance of mitochondrial morphology and of mitochondrial DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 278:27781-27788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrmann, J. M., and K. Hell. 2005. Chopped, trapped or tacked—protein translocation into the IMS of mitochondria. Trends Biochem. Sci. 30:205-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoogenraad, N. J., L. A. Ward, and M. T. Ryan. 2002. Import and assembly of proteins into mitochondria of mammalian cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1592:97-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarosch, E., R. Geiss-Friedlander, B. Meusser, J. Walter, and T. Sommer. 2002. Protein dislocation from the endoplasmic reticulum—pulling out the suspect. Traffic 3:530-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen, R. E., and A. E. Johnson. 2001. Opening the door to mitochondrial protein import. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8:1008-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koehler, C. M. 2004. New developments in mitochondrial assembly. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20:309-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koehler, C. M., E. Jarosch, K. Tokatlidis, K. Schmid, R. J. Schweyen, and G. Schatz. 1998. Import of mitochondrial carriers mediated by essential proteins of the intermembrane space. Science 279:369-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leonhard, K., A. Stiegler, W. Neupert, and T. Langer. 1999. Chaperone-like activity of the AAA domain of the yeast Yme1 AAA protease. Nature 398:348-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leszczyniecka, M., R. DeSalle, D. C. Kang, and P. B. Fisher. 2004. The origin of polynucleotide phosphorylase domains. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 31:123-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leszczyniecka, M., D. C. Kang, D. Sarkar, Z. Z. Su, M. Holmes, K. Valerie, and P. B. Fisher. 2002. Identification and cloning of human polynucleotide phosphorylase, hPNPase old-35, in the context of terminal differentiation and cellular senescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:16636-16641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leszczyniecka, M., Z. Z. Su, D. C. Kang, D. Sarkar, and P. B. Fisher. 2003. Expression regulation and genomic organization of human polynucleotide phosphorylase, hPNPase(old-35), a type I interferon inducible early response gene. Gene 316:143-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leuenberger, D., N. A. Bally, G. Schatz, and C. M. Koehler. 1999. Different import pathways through the mitochondrial intermembrane space for inner membrane proteins. EMBO J. 17:4816-4822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, Q. S., J. D. Gupta, and A. G. Hunt. 1998. Polynucleotide phosphorylase is a component of a novel plant poly(A) polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:17539-17543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lisitsky, I., A. Kotler, and G. Schuster. 1997. The mechanism of preferential degradation of polyadenylated RNA in the chloroplast. The exoribonuclease 100RNP/polynucleotide phosphorylase displays high binding affinity for poly(A) sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 272:17648-17653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luciano, P., S. Geoffroy, A. Brandt, J. F. Hernandez, and V. Geli. 1997. Functional cooperation of the mitochondrial processing peptidase subunits. J. Mol. Biol. 272:213-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mascorro-Gallardo, J. O., A. A. Covarrubias, and R. Gaxiola. 1996. Construction of a CUP1 promoter-based vector to modulate gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 172:169-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohanty, B. K., and S. R. Kushner. 2000. Polynucleotide phosphorylase functions both as a 3′ → 5′ exonuclease and a poly(A) polymerase in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:11966-11971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagaike, T., T. Suzuki, T. Katoh, and T. Ueda. 2005. Human mitochondrial mRNAs are stabilized with polyadenylation regulated by mitochondria-specific poly(A) polymerase and polynucleotide phosphorylase. J. Biol. Chem. 280:19721-19727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nolden, M., S. Ehses, M. Koppen, A. Bernacchia, E. I. Rugarli, and T. Langer. 2005. The m-AAA protease defective in hereditary spastic paraplegia controls ribosome assembly in mitochondria. Cell 123:277-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nunnari, J., T. D. Fox, and P. Walter. 1993. A mitochondrial protease with two catalytic subunits of nonoverlapping specificities. Science 262:1997-2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paschen, S. A., and W. Neupert. 2001. Protein import into mitochondria. I.U.B.M.B. Life 52:101-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfanner, N., H. K. Muller, M. A. Harmey, and W. Neupert. 1987. Mitochondrial protein import: involvement of the mature part of a cleavable precursor protein in the binding to receptor sites. EMBO J. 6:3449-3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piwowarski, J., P. Grzechnik, A. Dziembowski, A. Dmochowska, M. Minczuk, and P. P. Stepien. 2003. Human polynucleotide phosphorylase, hPNPase, is localized in mitochondria. J. Mol. Biol. 329:853-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rospert, S., and G. Schatz. 1998. Protein translocation into mitochondria, p. 277-285. In J. E. Celis (ed.), Cell biology: a laboratory handbook, 2nd ed., vol. 2. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ross, A. M., and E. E. Golub. 1988. A computer graphics program system for protein structure representation. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:1801-1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saelens, X., N. Festjens, L. Vande Walle, M. van Gurp, G. van Loo, and P. Vandenabeele. 2004. Toxic proteins released from mitochondria in cell death. Oncogene 23:2861-2874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sarkar, D., E. S. Park, and P. B. Fisher. 2006. Defining the mechanism by which IFN-beta dowregulates c-myc expression in human melanoma cells: pivotal role for human polynucleotide phosphorylase (hPNPase(old-35)). Cell Death Differ. 13:1541-1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schägger, H., W. A. Cramer, and G. von Jagow. 1994. Analysis of molecular masses and oligomeric states of protein complexes by blue native electrophoresis and isolation of membrane protein complexes by two-dimensional native electrophoresis. Anal. Biochem. 217:220-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmidt, B., and W. Neupert. 1984. Processing of precursors of mitochondrial proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 12:920-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Symmons, M. F., G. H. Jones, and B. F. Luisi. 2000. A duplicated fold is the structural basis for polynucleotide phosphorylase catalytic activity, processivity, and regulation. Structure 8:1215-1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Truscott, K. N., K. Brandner, and N. Pfanner. 2003. Mechanisms of protein import into mitochondria. Curr. Biol. 13:R326-R337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van der Bliek, A. M., and C. M. Koehler. 2003. A mitochondrial rhomboid protease. Dev. Cell 4:769-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.von Heijne, G. 1990. Protein targeting signals. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2:604-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.von Heijne, G., J. Steppuhn, and R. G. Herrmann. 1989. Domain structure of mitochondrial and chloroplast targeting peptides. Eur. J. Biochem. 180:535-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wachter, C., G. Schatz, and B. S. Glick. 1992. Role of ATP in the intramitochondrial sorting of cytochrome c1 and the adenine nucleotide translocator. EMBO J. 11:4787-4794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yaffe, M. P., and G. Schatz. 1984. Two nuclear mutations that block mitochondrial protein import in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:4819-4823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang, M. J., V. Geli, W. Oppliger, K. Suda, P. James, and G. Schatz. 1991. The MAS-encoded processing protease of yeast mitochondria. Interaction of the purified enzyme with signal peptides and a purified precursor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 266:6416-6423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yehudai-Resheff, S., M. Hirsh, and G. Schuster. 2001. Polynucleotide phosphorylase functions as both an exonuclease and a poly(A) polymerase in spinach chloroplasts. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:5408-5416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.