Abstract

DNA polymerase η (Pol η) is the product of the Polh gene, which is responsible for the group variant of xeroderma pigmentosum, a rare inherited recessive disease which is characterized by susceptibility to sunlight-induced skin cancer. We recently reported in a study of Polh mutant mice that Pol η is involved in the somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes, but the cancer predisposition of Polh−/− mice has not been examined until very recently. Another translesion synthesis polymerase, Pol ι, a Pol η paralog encoded by the Poli gene, is naturally deficient in the 129 mouse strain, and the function of Pol ι is enigmatic. Here, we generated Polh Poli double-deficient mice and compared the tumor susceptibility of them with Polh- or Poli-deficient animals under the same genetic background. While Pol ι deficiency does not influence the UV sensitivity of mouse fibroblasts irrespective of Polh genotype, Polh Poli double-deficient mice show slightly earlier onset of skin tumor formation. Intriguingly, histological diagnosis after chronic treatment with UV light reveals that Pol ι deficiency leads to the formation of mesenchymal tumors, such as sarcomas, that are not observed in Polh−/− mice. These results suggest the involvement of the Pol η and Pol ι proteins in UV-induced skin carcinogenesis.

Xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) is a rare inherited recessive disease characterized by severe sun sensitivity that leads to the progressive degeneration of exposed areas of skin, usually causing various forms of cutaneous malignancy (10). Mutations in seven of eight XP complementation groups, XP-A through -G, confer defects in the nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway, while cells from XP-V patients have a normal NER pathway but are defective in the replication of damaged DNA. To clarify the affected mechanisms in XP-V patients, our group previously isolated a protein from HeLa cells that complemented the defects of XP-V cell extracts (41, 43). The isolated protein was identified as polymerase η (Pol η), a DNA-dependent DNA polymerase that mediates high-fidelity synthesis of DNA past cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer (CPD), a major lesion induced by UV irradiation. At present, 10 DNA polymerases are known to exhibit translesion synthesis (TLS) activity (17), and the in vivo functions of these polymerases have been analyzed in several mutant mouse lines. At least eight mouse mutants defective in TLS polymerases have been reported (18, 25), and considerable attention has been paid to the involvement of these TLS polymerases in the somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes (13, 16, 25, 38, 40, 54, 75). We and another group independently demonstrated using Polh mutant mice that Pol η is involved in somatic hypermutation (13, 38). More recently, it has been reported (36) that Pol η-deficient mice developed skin tumors after UV irradiation, in contrast to the wild-type littermate controls that did not develop such tumors.

Here, we investigated the cancer predisposition of Polh, Poli, and Polh Poli double mutant mice subjected to UV irradiation. Since the 129-derived embryonic stem (ES) cell line, used to establish the Polh mouse mutant, is naturally defective in Poli (45), we also obtained Polh Poli double mutant mice as well as Poli mutant mice in a C57BL/6J genetic background. It has been reported that Pol ι does not contribute to murine somatic hypermutation (13, 39, 45, 55), but biochemical analysis has indicated that the mammalian Pol ι protein participates in TLS past UV-induced damage (27, 60, 63-65, 76). We, therefore, investigated the involvement of the Pol η and Pol ι proteins in the UV radiation sensitivity of murine fibroblasts and in susceptibility to UV-induced skin tumor formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Targeting of the murine Polh gene.

The Polh genomic sequence was obtained by screening a lambda DASH-129Sv mouse genomic library using a fragment containing nucleotides +264 through +1576 of the mouse Pol η cDNA (accession no. AB027128). A targeting vector for the Polh gene was constructed as follows. 5′ and 3′ halves (arms) of the vector were obtained by genomic PCR using the primer pairs 5′-GGAGCTCGAGTCCCAGCAAC-3′/5′-GTTCAATACGTCGACACATGGC-3′ and 5′-GCCATGTGTCGACGTATTGAAC-3′/5′-ATTGTAAAGAGCGGCCGCTTGGACTTG-3′, respectively (restriction enzyme recognition sites are underlined). PCR fragments for 5′ and 3′ arms were subcloned into the XhoI-SalI sites of pGEM-T Easy (Promega) and the SalI-NotI sites of pBluescript II KS(+) to generate pGEM-polη/5′arm and pBS-polη/3′arm, respectively. The XhoI-SalI fragment of pGEM-polη/5′arm, the 3.5-kb SalI-XhoI fragment of pSTneoB containing a neomycin resistance gene flanked by loxP sites (22) in the sense orientation, the SalI-NotI fragment of pBS-polη/3′arm, and the XhoI-SalI fragment of pMC1DTpA containing a diphtheria toxin A cassette (72) were joined using appropriate linker sequences of pBluescript II KS(+) to generate the targeting vector pBS-neoDTAXpolη. The targeting vector had the structure where the G418 resistance gene was inserted in the exon 8 sequence, and the sequence similarity to the genomic sequence extended 2.5 kb to the 5′ and 6.4 kb to the 3′.

The targeting vector was linearized and electroporated into the 129-derived ES line R1 (47). Viable G418-resistant colonies were screened for homologous recombinants by Southern blotting. BamHI-digested genomic DNA was hybridized with a probe containing exon 5 and 6 sequences of Pol η cDNA to confirm the 5′ junction of recombination, and EcoRI-digested genomic DNA was hybridized with a probe containing exon 10 and 11 sequences of Pol η cDNA to confirm the 3′ junction. The clones identified as homologous recombinants were further analyzed for the internal sequences by Southern blotting using the STneoB probe.

Generation of Polh Poli double mutant mice.

Two independent ES cell lines carrying the targeted Polh allele, designated Polhtm3Han, on chromosome 17 were injected into 3.5-day BDF1 blastocysts to generate chimeric mice. All animal protocols described in the manuscript were approved by the Animal Ethics Committees (Osaka University). Chimeric males, as judged by the coat color, were mated with C57BL/6J females, and germ line transmission of the genotype of the ES cells was determined by the coat color of the F1 mice. 129 mice have a natural nonsense mutation in exon 2 of the Poli gene on chromosome 18 (45). Since we used the 129-derived ES cell line to generate Polhtm3Han/Polhtm3Han (Polh−/−) mice, F1 mice were heterozygous for the Poli allele. Mice established from the two ES cell lines were indistinguishable in development, shape, behavior, and procreation. These mice were backcrossed to C57BL/6J female mice for more than five generations to obtain Polh+/− Poli+/− animals for analysis. Double heterozygotes were interbred to generate wild-type, Polh+/− Poli+/+, Polh−/− Poli+/+, Polh+/+ Poli+/−, Polh+/− Poli+/−, Polh−/− Poli+/−, Polh+/+ Poli−/−, Polh+/− Poli−/−, and Polh−/− Poli−/− mice. Mice were genotyped by PCR analysis of genomic DNA from ear or tail. The Polh allele was typed by PCR performed at 95°C for 30 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 2.5 min with 35 cycles, using primer pairs specific to exon 9 (5′-TTTCGATCTTTGGTTAGCCTCTCC-3′) and the intron of upstream exon 8 (5′-GTAGTCTGGGGGGTTGAATC-3′) for the wild-type allele and primer pairs Neo-Seq (5′-GTCTGTTGTGCCCAGTCATAGC-3′) and the intron for the mutant allele. Genotypes for Poli were determined as described elsewhere (45).

Isolation of MEFs, cell cultures, and establishment of spontaneously immortalized cell lines.

Primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) of each genotype were prepared from day 13.5 embryos. Embryos were minced and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum, glutamate, and antibiotics in a CO2 incubator. Cells were passaged at 1 × 106 cells/100-mm dish every 3 days and entered senescence after approximately 30 population doublings, after which spontaneously immortalized cells appeared.

UV-C radiation sensitivity of immortalized fibroblasts.

The UV sensitivity of immortalized fibroblasts was determined as previously described (70). Briefly, immortalized fibroblasts of all Polh Poli genotypes were exposed to increasing doses of UV-C (GL15; Toshiba) and allowed to grow for another 2 days with or without the addition of 1 mM caffeine before reaching confluence. The number of proliferating cells was estimated by scintillation counting of the radioactivity incorporated during a 1-h pulse with [3H]thymidine (5 Ci/ml; GE Healthcare). UV sensitivity was expressed as the percentage of 3H incorporation in treated and untreated cells.

Analysis of Polh and Poli gene expression.

The expression of Polh was monitored by Northern analysis. mRNA from MEF cells (5 × 106) grown to confluence was purified using the Micro-Fast Track mRNA isolation kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) according to instructions provided by the manufacturer. Samples (2 μg) were fractionated by electrophoresis in 1.2% agarose gels containing 6% formaldehyde and transferred to nylon membranes (Hybond-N; GE Healthcare). Probes for Polh were generated by PCR from the cDNA sequence as described above. Hybridization was performed overnight at 42°C in hybridization/prehybridization solution 2 (Clontech) containing probes randomly labeled with [α-32P]dCTP (GE Healthcare). The membranes were washed twice at room temperature with 2 × SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and 0.05% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and once at 42°C with 0.1× SSC and 0.1% SDS. Autoradiography was performed at −80°C with Hyperfilm MP (GE Healthcare). The same blot was stripped and incubated with probes specific for the neomycin gene or mouse GAPDH (GenBank accession no. M32599). Western blot analysis to detect mouse Pol η or Pol ι was performed with SDS lysate (60 μg) prepared from fibroblasts. Fibroblasts of all genotypes were lysed in buffer consisting of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 2% SDS, and 1× Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), and lysates were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Polyclonal antibodies against six-His-tagged recombinants of mouse Pol η lacking 320 to 553 amino acids or full-length Pol ι were used.

UV-induced tumor formation on mouse skin and histological diagnosis of lesions.

We used mice with the following genotypes in the assay of UV-induced skin carcinogenesis: wild-type (n = 25), Polh+/− Poli+/+ (n = 28), Polh−/− Poli+/+ (n = 25), Polh+/− Poli+/− (n = 8), Polh−/− Poli+/− (n = 19), Polh+/+ Poli−/− (n = 14), Polh+/− Poli−/− (n = 8), and Polh−/− Poli−/− mice (n = 22). In order to examine the tumor susceptibilities by UV-B irradiation, 8- to 12-week-old littermate mice were used. Their backs were shaved once a week and were irradiated at a dose of 2 kJ/m2 per day for 20 weeks with a narrow-band UV-B lamp (FL20S-E; Toshiba). All mice were checked once a week for the development of lesions on the dorsal skin and ears. Cumulative tumor incidence was evaluated by using the Kaplan-Meier method. Statistical significance was measured with the log-rank test. For histology, skin samples were prepared from each ear, dorsal side, and caudal side of back skin. The samples were fixed with 10% neutral-buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections were then prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histopathological diagnosis. Skin lesions were classified into epithelial lesions, including hyperplasia, dysplasia, sebaceous adenoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and adenosquamous cell carcinoma, and mesenchymal tumors, like sarcomas and hemangiomas. Hyperplasia is an increased thickness of the nonkeratinized epidermis. Dysplasia shows mild to severe nuclear atypia in thickened epidermis. Papilloma is characterized with exophytic growth. Sebaceous adenoma has clear sebaceous gland cells. Squamous cell carcinoma consists of atypical and sometimes bizarre squamous tumor cells with or without keratinization. Adenosquamous cell carcinoma possesses gland-forming tumor cells as well as a squamous cell carcinoma component. Sarcoma is characterized with a proliferation of spindle-shaped neoplastic cells. Hemangioma consists of endothelial cells containing red blood cells (6, 49). For statistical analysis of tumor incidence on UV-irradiated mice after histological diagnosis, statistical significance was measured by using Fisher's exact probability test.

RESULTS

Generation of Polh-deficient mice.

To elucidate the in vivo function of the Pol η protein and the molecular basis of the group V XP phenotype, we generated Polh mutant mice carrying the Polhtm3Han allele by targeted gene replacement. A G418 resistance gene cassette, STneoB, was inserted into the exon 8 sequence of the Polh gene, resulting in production of a truncated nonfunctional Pol η protein (Fig. 1A). Since the STneoB cassette inserted in the sense orientation carried a polyadenylation signal, transcription of the Polhtm3Han allele was expected to terminate concomitantly. 129 mouse-derived ES cell line R1 (47) was electroporated with the targeting vector, selected for G418 resistance, and screened for homologous recombination by Southern blot analysis using probes external to the targeting vector sequence (Fig. 1A), and Polh/Polh3Han (Polh+/−) ES clones were isolated. As 129 mice carry spontaneous Poli nonsense mutations (45), this recombination imposed cells with the Polh+/− Poli−/− genetic composition. The targeted ES cells were injected into blastocysts of BDF1 mice to produce male mouse chimera, and successful transmission of the targeted allele upon crossing with C57BL/6J females resulted in production of the Polh+/− Poli+/− mice. These mice were crossed with C57BL/6J mice at least five generations, and the Polh+/− Poli+/− mice were then intercrossed to obtain all nine possible genotypes: wild-type, Polh+/− Poli+/+, Polh−/− Poli+/+, Polh+/+ Poli+/−, Polh+/− Poli+/−, Polh−/− Poli+/−, Polh+/+ Poli−/−, Polh+/− Poli−/−, and Polh−/− Poli−/− mice. Mice of these genotypes were born with a ratio expected from the Mendelian transmission, and Polh−/− Poli−/− mice were apparently normal in development, gross morphology, behavior, and fertility. This indicates that Polh and Poli are dispensable for development under the laboratory conditions. MEFs were also derived from day 13.5 embryos for each genotype.

FIG. 1.

Targeted disruption of the mouse Polh gene. (A) Schematic representation of the targeting strategy for the mouse Polh locus. The coding exons are numbered and boxed. The positions of selected restriction sites are shown. (B) Southern blot analysis of EcoRI-digested (for the 3′ and neo probes) or BamHI-digested (for the 5′ probe) genomic DNA and Northern blot analysis of mRNA prepared from MEFs. The position of each probe is shown in panel A. For Northern blot analysis, hybridization with a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)-specific probe was performed to normalize for RNA amounts and transfer efficiency.

The mutated Polh allele encodes a nonfunctional Pol η protein.

Genomic DNA and mRNAs from wild-type, Polh+/− Poli+/+, and Polh−/− Poli+/+ fibroblasts were subjected to Southern and Northern blot analyses, respectively, as shown in Fig. 1B. As previously shown (70), a 3.2-kb mRNA transcribed from the wild-type Polh allele was detected with both 5′ and 3′ probes for RNA prepared from wild-type and Polh+/− Poli+/+ mice but not Polh−/− Poli+/+ mice. On the other hand, a 1.7-kb mRNA was detected for the Polh+/− Poli+/+ and Polh−/− Poli+/+ genotypes with the 5′ probe. Sequence analysis revealed that the 1.7-kb mRNA is derived from the targeted Polh allele and that it consists of sequences from exons 1 through 7 of Polh and part of the simian virus 40 terminator of the neomycin cassette.

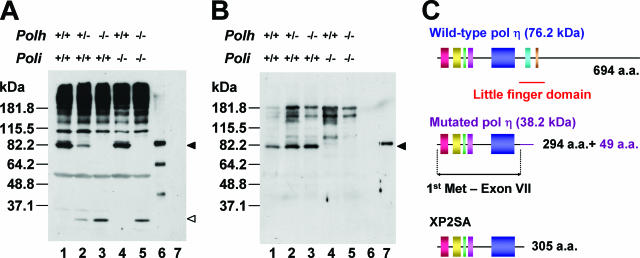

The effect of targeted disruption on Pol η protein expression was examined by Western blot analysis in immortalized fibroblasts with these three genotypes (Fig. 2A). A polyclonal antibody against the mouse Pol η protein detected an approximately 83-kDa protein in extracts of wild-type cells (lane 1). This protein was slightly larger than that predicted from the translated amino acid sequence of the mouse Polh gene (see also Fig. 2C) but correlated well with that predicted for purified six-His-tagged recombinant Pol η protein expressed in insect cells (Fig. 2A, lane 6). This protein was expressed at reduced levels in Polh+/− Poli+/+ cells (Fig. 2A, compare lanes 1 and 2) and was undetectable in Polh−/− Poli+/+ and Polh−/− Poli−/− cells (Fig. 2A, compare lanes 1 and 3 and compare lanes 4 and 5). However, a small protein could be detected in Polh+/− Poli+/+, Polh−/− Poli+/+, and Polh−/− Poli−/− cell extracts with the anti-Pol η antibody (Fig. 2A, lanes 2, 3, and 5). The protein predicted from the 1.7-kb transcript (Fig. 1B) from the targeted Polh allele should consist of 343 amino acids, 294 encoded by exons 1 though 7 and 49 encoded by the simian virus 40 terminator. The size of this predicted protein was almost the same as that of proteins observed in Polh+/− Poli+/+, Polh−/− Poli+/+, and Polh−/− Poli−/− cell extracts (Fig. 2A, lanes 2, 3, and 5). In any case, this small Pol η protein derived from the mutated Polh allele should be deficient in TLS activity, since it lacks an essential domain designated the polymerase-associated domain (PAD)/little finger domain/wrist (4, 37, 56, 61) and resembles the expected product (305 amino acids) of the mutated Polh allele of human XP2SA cells (5, 74) (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, analysis of human Pol η mutants reveals that the domain absent from mutated murine Pol η is indeed essential for TLS activity in vitro (Y. Kondo, C. Masutani, and F. Hanaoka, unpublished data). We thus conclude that functional Pol η is not expressed from the targeted Polh allele. As previously reported (45), the absence of Pol ι protein from Poli−/− fibroblasts was also confirmed using an anti-Pol ι antibody (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Expression of the Pol η and Pol ι proteins in MEFs. (A) Expression of Pol η in MEFs was monitored with a polyclonal antibody (60 μg/lane). The positions of the intact Pol η protein expressed by the wild-type allele and the truncated protein derived from the mutated allele are indicated by the filled and open arrowheads, respectively. Purified six-His-tagged mouse Pol η (0.5 ng) was used as a size marker (lane 6). (B) Expression of the Pol ι protein in MEFs was monitored with a polyclonal antibody (60 μg/lane) after stripping anti-Pol η antibody from the membrane shown in panel A. The position of the intact Pol ι protein is indicated by the filled arrowhead. Purified six-His-tagged mouse Pol ι (0.5 ng) was used as a size marker (lane 7). (C) Schematic of the protein derived from the mutant Polh allele. Highly conserved regions shared by Y-family polymerases are indicated. Like the predicted Pol η protein in human XP2SA cells, the truncated Pol η protein from the 1.7-kb transcript (Fig. 1B) from the mutated allele lacks part of the highly conserved domain essential for TLS activity but has an extra 49 amino acids derived from the sequence of the neomycin resistance gene cassette on the carboxy terminus.

Hypersensitivity of Polh−/− Poli+/+ fibroblasts to UV-C irradiation.

To investigate the basis for susceptibility to UV-induced skin cancers, we first analyzed the cellular sensitivity of immortalized fibroblasts from all Polh Poli genotypes after exposure to increasing doses of UV-C irradiation. As shown in Fig. 3A, Polh−/− Poli+/+ and Polh−/− Poli−/− fibroblasts exhibited significant sensitivity to UV irradiation, whereas fibroblasts of other genotypes were insensitive. The sensitivity of Polh-deficient cells was strongly enhanced by the addition of 1 mM caffeine (Fig. 3B). Caffeine is known to inhibit various ionizing radiation- and UV-induced cell cycle checkpoints that are ATM- and/or ATR-dependent (reviewed in reference 29). The UV radiation sensitivity of Pol η-deficient fibroblasts corresponded well with that of fibroblasts from human XP-V patients (1, 34). In contrast, disruption of the Pol ι protein had no effect on UV sensitivity, even in the presence of caffeine or in a Pol η-deficient background.

FIG. 3.

Effects of UV irradiation on cell proliferation. (A and B) MEFs were irradiated as indicated with UV-C. After irradiation, cells were cultured in the absence (A) or the presence (B) of 1 mM caffeine for 2 days. The number of proliferating cells was measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation. All experiments were performed in duplicate at least three times. Consistent results were obtained for different sets of experiments. Data are presented as mean survival rates ± standard deviations. wt, wild type.

Skin tumor predisposition of Polh−/− Poli+/+ mice chronically exposed to UV irradiation.

To confirm whether Polh-deficient mice are prone to UV-induced skin cancers, like XP-V patients, and to determine whether mutation of the Poli allele causes skin tumor formation, we chronically exposed shaved dorsal skin of mice of all Polh Poli genotypes to UV-B light at a dose of 2 kJ/m2/day for 20 weeks. Although none of the unirradiated Polh-deficient mice showed signs of tumors on ears or dorsal skin (Table 1), UV-irradiated Polh−/− Poli+/+ mice started to develop skin tumors 13 weeks after the beginning of treatment (Fig. 4A). After 20 weeks of irradiation, approximately 90% of Polh−/− Poli+/+ mice developed multiple tumors on the dorsal skin and predominantly on the ears, whereas visible tumors did not form on the dorsal skin or ears of wild-type, Polh+/− Poli+/+, and Polh+/+ Poli−/− mice. The high incidence of skin tumors in Polh−/− Poli+/+ mice (P < 0.0001 versus wild-type mice) corresponds well with our previous observation that mouse Pol η has a function similar to that of human Pol η in vivo (70).

TABLE 1.

Results of histopathological examination of UV-exposed (2 kJ/m2/day for 5 and 10 weeks) and control mice

| UV (wks) | Genotype

|

Total no. of mice | No. of mice with skin abnormality (P value)a

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polh | Poli | Hyperplasia | Dysplasia | Epithelial skin tumor | Mesenchymal skin tumor | ||

| 0 | −/− | −/− | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | −/− | +/− | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | −/− | +/+ | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | +/− | +/+ | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | +/+ | −/− | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | +/+ | +/+ | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | −/− | +/+ | 6 | 6 (0.0076) | 2 (0.227) | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| 5 | +/− | +/+ | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | −/− | +/+ | 3 | 0 | 3 (0.0119) | 2 (0.0833) | 0 |

| 10 | +/− | +/+ | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The statistical significance of skin abnormalities identified by histological diagnosis was measured between Polh−/− Poli+/+ and Polh+/− Poli+/+ mice treated under the same experimental condition, using Fisher's exact probability test. Bold indicates P < 0.05; bold underlining indicates 0.05 ≤ P < 0.10.

FIG. 4.

Tumorigenesis induced by chronic treatment with UV-B. (A) Kaplan-Meier curves of mice free of skin tumors after chronic UV irradiation (2 kJ/m2/day). (B) Number of UV-induced skin tumors per animal. Bars represent the exposure period. wt, wild type.

On the other hand, inactivation of Pol ι protein alone did not promote the development of skin tumors in Pol η-proficient mice. Although there was no statistically significant increase in tumorigenesis for mice of the Polh−/− genetic background after treatment, Polh−/− Poli+/− and Polh−/− Poli−/− mice started to develop skin tumors 4 weeks earlier than Polh−/− Poli+/+ mice (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the average number of dorsal skin tumors was slightly but significantly higher for Polh−/− Poli−/− mice than for Polh−/− Poli+/+ mice (P = 0.029), while there was no visible tumor formation on the dorsal skin of Polh+/+ Poli−/− mice (Fig. 4B). For example, there were 0, 4.1, and 5.9 tumors per animal for wild-type, Polh−/− Poli+/+, and Polh−/− Poli−/− mice, respectively, 22 weeks after the start of treatment. These observations suggest that the Pol ι protein may have a minor role in suppressing UV-induced epithelial tumor development in the Pol η-deficient background.

Epithelial tumor formation in Pol η-deficient mice after chronic UV irradiation.

To more precisely examine the influence of Polh and Poli mutations on UV-induced skin alterations, several mutant mouse lines were subjected to histological diagnosis after UV irradiation. Wild-type, Polh+/− Poli+/+, and Polh−/− Poli+/+ mice were irradiated with UV-B for 5-week, 10-week, and 20-week periods, at a dose rate of 2 kJ/m2/day, and sacrificed 10 weeks after each irradiation regimen. The ears and dorsal skin of these mice were examined (Tables 1 and 2 and Fig. 5).

TABLE 2.

Results of histopathological examination of UV-exposed (2 kJ/m2/day for 20 weeks) mice

| Genotype | Group | Total no. of mice | No. of mice with abnormality (P value[s])a

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polh | Poli | Hyperplasia | Dysplasia | Epithelial skin tumor | Mesenchymal skin tumor | Metastasis | ||

| −/− | −/− | A | 19 | NDb | ND | 19 (0.592 vs C; 0.004 vs D) | 3 (0.125 vs C; 0.472 vs G) | 3 (0.585 vs B; 0.125 vs C) |

| −/− | +/− | B | 16 | ND | ND | 16 (0.596 vs C; 0.0013 vs E) | 0 | 2 (0.214 vs C) |

| −/− | +/+ | C | 18 | ND | ND | 18 (0.0072 vs F; 0.0001 vs H) | 0 | 0 |

| +/− | −/− | D | 8 | 5 (0.437 vs F; 0.5 vs G) | 5 (0.117 vs F; 0.696 vs G) | 4 (0.601 vs F; 0.141 vs G) | 3 (0.0824 vs F; 0.5 vs G) | 0 |

| +/− | +/− | E | 8 | 2 (0.109 vs F) | 5 (0.117 vs F) | 3 (0.399 vs F) | 0 | 0 |

| +/− | +/+ | F | 9 | 7 (0.117 vs H) | 2 (0.265 vs H) | 5 (0.0204 vs H) | 0 | 0 |

| +/+ | −/− | G | 8 | 4 (0.5 vs H) | 5 (0.0128 vs H) | 1 (0.5 vs H) | 2 (0.233 vs H) | 0 |

| +/+ | +/+ | H | 8 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The statistical significance of skin abnormalities identified by histological diagnosis was measured with Fisher's exact probability test. Bold indicates P < 0.05; bold underlined indicates 0.05 ≤ P < 0.10.

ND, not demonstrated.

FIG. 5.

Histopathological examination of UV-B-induced skin tumors from Polh Poli double knockout mice. (A) Left and right panels represent typical examples of normal skin histology and dysplasia observed in wild-type mice, respectively. (B and C) Typical examples of squamous cell carcinoma predominantly observed in Polh−/− Poli+/+ mice (B) and Polh−/− Poli−/− mice (C). (D) Soft tissue sarcoma found in a Polh−/− Poli−/− mouse. White arrows indicate squamous cell carcinomas adjacent to the sarcoma.

No remarkable change was observed for unirradiated mice of all three genotypes (Table 1). Moreover, 5- and 10-week exposures to UV-B irradiation did not noticeably affect Polh+/− Poli+/+ mice, except for one animal which showed hyperplasia following a 5-week exposure. However, there was a high incidence of hyperplasia (six of six) and dysplasia (three of three) in Polh−/− Poli+/+ mice compared to Polh+/− Poli+/+ mice following 5 and 10 weeks of UV-B irradiation, respectively (hyperplasia, P = 0.0076; dysplasia, P = 0.0119) (Table 1). Furthermore, epithelial skin tumors (such as squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous cell carcinoma, papilloma, and sebaceous adenoma) also developed on the dorsal skin and/or ears of Polh−/− Poli+/+ mice exposed to 5 and 10 weeks of UV irradiation (Table 1); however, there was no statistical significance between Polh−/− Poli+/+ and Polh+/− Poli+/+ mice with respect to tumor incidence (P = 0.5 for 5 weeks UV of irradiation; P = 0.0833 for 10 weeks of UV irradiation) (Table 1). On the other hand, epithelial tumor formation was evident in Polh−/− Poli+/+ mice UV irradiated for 20 weeks (18 of 18 Polh−/− Poli+/+ mice versus 0 of 8 wild-type mice, P < 0.0001; 18 of 18 Polh−/− Poli+/+ mice versus 5 of 9 Polh+/− Poli+/+ mice, P = 0.0072) (Table 2 and Fig. 6). Intriguingly, skin tumor formation was observed on four of nine Polh+/− Poli+/+ mice during a 10-week interval after the 20-week irradiation regimen (Fig. 4A). Histological diagnosis revealed that five of nine Polh+/− Poli+/+ mice developed epithelial tumors on dorsal skin or ears (five of nine Polh+/− Poli+/+ mice versus zero of eight wild-type mice, P = 0.0204). These data indicate that loss of a single allele of Polh has phenotypic consequences.

FIG. 6.

Incidence of skin tumors after chronic UV exposure in mice bearing various combinations of Polh and Poli alleles. Gray, dark gray, and white bars indicate Poli+/+, Poli+/−, and Poli−/− mice, respectively. We have not examined Polh+/+ Poli+/− mice. (A) Incidence of epithelial skin tumors. *, values for Polh−/− mice are statistically significant versus those of corresponding Polh+/− mice (P = 0.0072 for Poli+/+, P = 0.0013 for Poli+/−, and P = 0.004 for Poli−/−, respectively); **, value for Polh+/− mice is statistically significant versus that of Polh+/+ mice (P = 0.0204). (B) Incidence of mesenchymal skin tumors. *, value for Poli−/− mice is statistically significant versus that of Poli+/− mice (P = 0.0106); **, value for Poli−/− mice is statistically significant versus that of Poli+/+ mice (P = 0.0025).

Other organs were carefully examined macroscopically and microscopically. Lung tumors were found surrounded by pulmonary alveolar tissues in 3 of 19 Polh−/− Poli−/− and 2 of 16 Polh−/− Poli+/− animals and were revealed as squamous cell carcinomas resembling skin cancers (Table 2). Since there were no squamous metaplastic lesions in bronchi and bronchioles, the lung tumors were considered metastasis from the skin lesions.

Pol ι deficiency induces mesenchymal tumor development after UV-B exposure.

To elucidate the in vivo function of Pol ι, we also carried out histological analyses on Polh Poli double mutant mice that were UV irradiated for 20 weeks (Table 2). Epithelial tumors developed in all animals of the Polh−/− genetic background irrespective of Poli genotype. The incidence of epithelial skin tumors in Polh−/− mice compared to Polh+/− mice with respect to the Poli genotype was as follows: 19 of 19 Polh−/− Poli−/− mice versus 4 of 8 Polh+/− Poli−/− mice, P = 0.004; 16 of 16 Polh−/− Poli+/− mice versus 3 of 8 Polh+/− Poli+/− mice, P = 0.0013; and as indicated above, Polh−/− Poli+/+ mice versus Polh+/− Poli+/+ mice, P = 0.0072. Thus, loss of the Poli allele did not significantly influence the incidence of epithelial skin tumors, regardless of Polh genotype. In contrast, mesenchymal skin tumors such as sarcomas and hemangiomas formed only in Poli−/− mice after 20 weeks of UV irradiation (3 of 19 Polh−/− Poli−/− mice versus 0 of 18 Polh−/− Poli+/+ mice, P = 0.125; 3 of 8 Polh+/− Poli−/− mice versus 0 of 9 Polh+/− Poli+/+ mice, P = 0.0824; 2 of 8 Polh+/+ Poli−/− mice versus 0 of 8 wild-type mice, P = 0.233). In addition, the incidence of dysplasia in Polh+/+ Poli−/− mice was also significant compared to that in wild-type mice (P = 0.0128).

The tumor incidences with respect to Polh and Poli genotypes after 20 weeks of UV irradiation (2 kJ/m2/day) are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 6. It is significant that loss of a single Polh allele increases the risk of UV-induced epithelial skin tumors such as squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous cell carcinoma, squamous papilloma, and sebaceous adenoma (Polh−/− genotype versus Polh+/− genotype, P < 0.0001; Polh−/− genotype versus Polh+/+ genotype, P < 0.0001; Polh+/− genotype versus Polh+/+ genotype, P = 0.005) (Table 3; Fig. 5B and C and 6). Furthermore, the formation of the mesenchymal tumors, such as sarcoma or hemangioma, by chronic UV irradiation was enhanced in Poli−/− mice (Poli−/− genotype versus Poli+/− genotype, P = 0.0025; Poli−/− genotype versus Poli+/+ genotype, P = 0.0106) (Table 3 and Fig. 5D and 6).

TABLE 3.

Incidence of skin abnormalities after chronic UV exposure (2 kJ/m2/day for 20 weeks) of mice bearing various combinations of Polh and Poli alleles

| Genotype | Total no. of mice | No. of mice with abnormality (P value[s])a

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polh | Poli | Hyperplasia/dysplasia | Epithelial skin tumor | Mesenchymal skin tumor | Metastasis | |

| −/− | Allb | 53 | NDc | 53 (<0.0001 vs Polh+/−; <0.0001 vs Polh+/+) | 3 (0.289 vs Polh+/−; 0.922 vs Polh+/+) | 5 (0.136 vs Polh+/−) |

| +/− | Allb | 25 | 23 (0.0107 vs Polh+/+) | 12 (0.005 vs Polh+/+) | 3 (0.709 vs Polh+/+) | 0 |

| +/+ | Allb | 16 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Alld | −/− | 35 | 15 (0.214 vs Poli+/−; 0.159 vs Poli+/+) | 23 (0.205 vs Poli+/−; 0.599 vs Poli+/+) | 8 (0.0106 vs Poli+/−; 0.0025 vs Poli+/+) | 3 (0.5 vs Poli+/−; 0.12 vs Poli+/+) |

| Alld | +/− | 24 | 7 (0.636 vs Poli+/+) | 19 (0.205 vs Poli+/+) | 0 | 2 (0.246 vs Poli+/+) |

| Alld | +/+ | 35 | 10 | 23 | 0 | 0 |

Data were derived from Table 2. The statistical significance of tumor incidence in UV-irradiated mice was measured with Fisher's exact probability test. Bold, P < 0.05.

Poli−/−, Poli+/−, and Poli+/+.

ND, not demonstrated.

Polh−/−, Polh+/−, and Polh+/+.

DISCUSSION

Polh-deficient mice as an XP-V model.

In the present study, we established mice lacking the Pol η and/or Pol ι protein to investigate the involvement of TLS polymerases in cancer predisposition induced by environmental factors. Following UV irradiation, the cellular survival and predisposition to cancer of Pol η-deficient fibroblasts and mice, respectively, correlated well with observations made of human XP-V patients.

Histopathological analysis revealed that the absence of mouse Pol η provokes a susceptibility to cancer induced by UV-B irradiation, with a predominance of squamous cell carcinomas at various stages of differentiation (Fig. 5B). Although malignant melanoma, a typical skin tumor found in sun-exposed areas of XP-V patients, was not observed, even after 20 weeks of UV irradiation of a cohort of Polh−/− Poli+/+ mice, this is simply due to architectural and functional differences between mouse and human skin. Namely, melanocytes are absent from the mouse epidermis but present in the dermis, whereas in human skin they are dispersed among epidermal keratinocytes. Therefore, overexpression of a stem cell factor, the ligand for the c-Kit receptor tyrosine kinase, may induce malignant melanomas in UV-irradiated mouse skin (71). As a comparison, NER-deficient mice, such as XPA-deficient mice (15, 48) and XPC-deficient mice (8, 53), do not get melanomas.

Importantly, we observed tumor development in about 50% of Polh+/− Poli+/+ mice after 20 weeks of UV irradiation. As shown in Fig. 4A, there were no visible tumors in Polh+/− Poli+/+ mice for 22 weeks after the start of UV irradiation. Thus, tumors found in the other half of these UV-irradiated Polh+/− Poli+/+ mice were likely to have developed during the 10-week resting period prior to diagnosis; however, skin tumors were not observed for wild-type mice under the same conditions. The increasing incidence of tumors in mice lacking only one Polh allele indicates that heterozygous XP-V patients may be more susceptible to cancer than are normal individuals that are chronically exposed to sunlight. Similar results for UV-induced skin carcinogenesis in an independently generated mouse deficient for a single allele of Pol η were recently reported by Lin et al. (36).

Itoh et al. demonstrated that XP-V heterozygous cells are slightly more sensitive to UV than wild-type cells in the presence of 1 mM caffeine because the level of recovery of replicative DNA synthesis is reduced in these cells (23). Since mouse fibroblasts heterozygous for Polh are not sensitive to caffeine (Fig. 3B), the mechanism of skin cancer susceptibility in Polh heterozygous mice is still obscure.

Role for Pol ι in prevention of UV-induced mesenchymal tumors.

A notable finding is that mesenchymal tumors, such as sarcomas or hemangiomas, are significantly developed in mouse skin as a result of Pol ι deficiency following 20 weeks of UV irradiation (Table 3 and Fig. 5D). Several in vitro experiments have indicated that the Pol ι protein participates in the bypass of two major UV-induced DNA lesions, CPDs and pyrimidine(6-4)pyrimidone photoproducts [(6-4)PPs] (27, 60, 63-65, 76). According to these previous studies, Pol ι protein bypasses thymine-thymine CPDs in a highly error-prone manner under certain conditions (60, 63, 64). In contrast, however, Pol ι-dependent synthesis past uracil-containing CPDs, which are generated as a result of deamination of cytosine, is relatively accurate, in contrast to synthesis mediated by Pol η and Pol κ (65, 66). As observed for (6-4)PPs, the Pol ι protein preferentially incorporates the correct nucleotide dAMP opposite the 3′ T of (6-4)PPs in vitro (27, 60, 63, 64, 76), although (6-4)PPs are rapidly removed from the genome by the NER pathway. These findings support the idea that Pol ι has a role in the low frequency of mutations induced by UV lesions in mammalian cells.

Previous reports have strongly indicated a genetic linkage between chemical-induced lung tumor formation and Pol ι deficiency in BALB/cJ and A/J mice (31, 32, 68). These findings have suggested that the Pol ι protein may be involved in preventing certain tumors. On the other hand, the incidence of spontaneous mesenchymal skin tumors, such as sarcomas or hemangiomas, is lower than that of lung and Harderian gland tumors in 129S4/SvJae mice (69). Moreover, we found that unirradiated Poli-deficient mice do not develop skin tumors (Table 1). We, therefore, conclude that UV-induced DNA lesions are primarily responsible for mesenchymal skin tumor formation in UV-irradiated Poli-deficient mice. It is not the only case for development of mesenchymal skin tumors in UV-irradiated repair-deficient mice. It has been reported that corneal hemangiosarcomas were observed in Csa−/− Xpc−/− mice (67).

Differential repair of UV lesions in epithelial and mesenchymal cells.

UV-induced lesions are removed from the genome by the efficient NER pathway. In contrast, it is accepted that NER activity is considerably lower in mouse fibroblasts than in human cells (21). Quantitative analysis of UV-B (500-J/m2)-induced DNA lesions in mouse skin using damage-specific antibodies has revealed differences in the repair efficiencies of CPDs and (6-4)PPs in epidermis and dermis (51). Most (6-4)PPs are rapidly removed within 3 days from both epidermis and dermis in C3H/HeN mice. In contrast, the removal of CPDs from both tissues is gradual for the first 24 h. Although more than 80% of CPDs are removed from epidermal cells within 5 days, less than 50% of CPDs are removed from dermal fibroblasts during this time. These characteristics of skin tissues in the removal of UV lesions are consistent with the repair rates of UV lesions observed in mouse and human cultured epidermal keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts (11, 12, 14, 46, 52). Accordingly, the repair rate of (6-4)PPs is similar for the two cell types, whereas CPDs are removed significantly faster from keratinocytes than from fibroblasts. In general, however, CPD lesions are removed more slowly from the genome than (6-4)PPs, probably because of the distinct affinity of the global genome NER (GG-NER)-specific XPC protein complex for these UV lesions (3, 30, 57). Besides the difference in repair rates for the two photolesions in vivo, You et al. reported that CPDs are responsible for the majority of UV-B-induced mutations in a mammalian mutagenesis assay system (73). Using transgenic mice carrying a specific photolyase for CPD or (6-4)PP, Jans et al. also demonstrated that the CPD lesion is the principal cause of cell death, mutation, and skin cancer (24).

These previous observations suggest that UV-induced CPDs are most likely responsible for epithelial tumor development in Polh-deficient mice and mesenchymal tumor formation in mice lacking the Pol ι protein. Another factor to explain the tumor spectrum of Poli versus Polh mice could be a difference in proliferation rates between keratinocytes and fibroblasts, for instance, allowing repair of UV lesions over a longer period.

Hypothesis concerning UV-induced skin tumors in Polh- and/or Poli-deficient mice.

A quantitative analysis of dipyrimidine photoproducts using a high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry system was performed on DNA from UV-B-irradiated human fibroblasts (11, 12). According to these reports, in the case of CPDs the formation of thymine-thymine photoproducts was twice that of thymine-cytosine photoproducts. Moreover, the levels of cytosine-thymine and cytosine-cytosine photolesions were almost undetectable in the dose range studied. Thus, two-thirds and one-third of UV-induced CPDs in cells are thymine-thymine and thymine-cytosine photoproducts, respectively. On the other hand, it was clearly shown that thymine-thymine CPDs are largely bypassed in an accurate manner by human Pol η (28, 41, 42). Hence, inactivation of Pol η renders cells hypermutable and mice susceptible to cancer by UV irradiation. However, Pol η-dependent synthesis on CPDs containing cytosine residues is often error-prone because of the deamination of cytosine in CPDs in vivo (33, 50, 59). That is, the deamination of cytosine produces a uracil-containing CPD, which frequently induces C-to-T transitions after Pol η-dependent error-free synthesis (58), although uracil residues and uracil/guanine mispairs are preferentially removed by the base excision repair and mismatch repair pathways, respectively. The in vivo deamination of cytosines in CPDs takes from several hours to a few days, depending on local sequence context (2, 7, 33, 50, 59, 62). Taking these results together, it is likely that cytosine residues in dermal CPDs are more likely to be deaminated than those in epidermal CPDs, since these lesions persist longer in the dermis than in the epidermis, as mentioned above.

A recent in vitro study by Vaisman et al. suggested that the Pol ι-dependent misincorporation of guanine residues opposite the 3′ U of thymine-uracil CPDs may suffice to prevent C-to-T transitions at cytosine-containing CPD sites in vivo (65, 66). Thus, we hypothesize that the failure of thymine-uracil CPDs to be bypassed in this manner is responsible for the significant development of mesenchymal skin tumors in UV-irradiated Poli−/− mice. On the other hand, inactivation of Pol ι in Polh-deficient mice hastens the onset of UV-induced tumor formation in epidermis and increases the number of epithelial skin tumors per animal (Fig. 4), although Polh+/+ Poli−/− mice do not develop epithelial skin tumors. Thus, it is likely that Pol ι makes a minor contribution to the suppression of epidermal tumor formation by the error-free bypass of thymine-uracil CPDs. We are currently studying the mutation spectra of tumors formed in UV-B-exposed skin of mice lacking the Pol η and/or Pol ι proteins. In addition, metastasis was identified only in Polh-deficient mice lacking at least one Poli allele (Table 2). It is known that not only mesenchymal tumors but also squamous cell carcinomas could metastasize (44). In any case, metastasis reflects a higher degree of malignancy, and it will be interesting to analyze the molecular basis of these phenomena.

Several studies using small interfering RNA on mammalian TLS polymerases have shown that Rev1 and Rev3, but not Pol ι, are clearly required in UV-induced mutagenesis (9, 19, 20, 26, 35). However, it is currently unknown what kind of mechanism is involved in the observed hypermutability of XP-V cells. To reveal the precise mechanism of UV-induced skin tumor formation in Polh−/− and Poli−/− mice, similar experiments should be performed in GG-NER (XPC)-deficient mice, in mismatch repair mutants, or in the presence of constitutively expressed damage-specific photolyases, accompanied by mutational spectra analysis. Some of these experiments are under way.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that Pol η is required to prevent the deleterious outcomes of UV-induced photolesions in mice as well as in humans. In particular, our results predict that loss of only one allele of Polh has phenotypic consequences. Furthermore, we have shown that lack of Pol ι protein indeed confers a predisposition to UV-induced mesenchymal tumorigenesis. This is the first direct evidence that evokes a protective role for the Pol ι protein in carcinogenesis. Finally, we confirm the usefulness of these mouse mutants for studying the role of TLS in cancer susceptibility induced by environmental factors.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the members of the Hanaoka laboratory at Osaka University for their critical discussions and comments. We also thank Kazuo Hara, Department of Pathology, Aichi Medical University, Japan, for valuable discussion about skin lesions.

This work was supported by KAKENHI (Grant-in Aid for Scientific Research) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (17012003 to M.T., 12CE2007 to H.K., and 17013053 to F.H.), by the Human Frontier Science Program, and by Solution Oriented Research for Science and Technology from the Japan Science and Technology Agency. This work was also supported by the Bioarchitect Research Project and the Chemical Biology Project of RIKEN.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arlett, C. F., S. A. Harcourt, and B. C. Broughton. 1975. The influence of caffeine on cell survival in excision-proficient and excision-deficient xeroderma pigmentosum and normal human cell strains following ultraviolet-light irradiation. Mutat. Res. 33:341-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barak, Y., O. Cohen-Fix, and Z. Livneh. 1995. Deamination of cytosine-containing pyrimidine photodimers in UV-irradiated DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 270:24174-24179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batty, D., V. Rapic'-Otrin, A. S. Levine, and R. D. Wood. 2000. Stable binding of human XPC complex to irradiated DNA confers strong discrimination for damaged sites. J. Mol. Biol. 300:275-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boudsocq, F., R. J. Kokoska, B. S. Plosky, A. Vaisman, H. Ling, T. A. Kunkel, W. Yang, and R. Woodgate. 2004. Investigating the role of the little finger domain of Y-family DNA polymerases in low fidelity synthesis and translesion replication. J. Biol. Chem. 279:32932-32940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broughton, B. C., A. Cordonnier, W. J. Kleijer, N. G. J. Jaspers, H. Fawcett, A. Raams, V. C. Garritsen, A. Stary, M.-F. Avril, F. Boudsocq, C. Masutani, F. Hanaoka, R. P. Fuchs, A. Sarasin, and A. R. Lehmann. 2002. Molecular analysis of mutations in DNA polymerase η in xeroderma pigmentosum-variant patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:815-820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruner, R., K. Küttler, R. Bader, W. Kaufmann, A. Boothe, M. Enomoto, J. M. Holland, and W. E. Parish. 2001. Integumentary system, p. 1-22. In U. Mohr (ed.), International classification of rodent tumors: the mouse. WHO/International Agency for Research on Cancer. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany.

- 7.Burger, A., D. Fix, H. Liu, J. Hays, and R. Bockrath. 2003. In vivo deamination of cytosine-containing cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers in E. coli: a feasible part of UV-mutagenesis. Mutat. Res. 522:145-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheo, D. L., L. B. Meira, R. E. Hammer, D. K. Burns, A. T. B. Doughty, and E. C. Friedberg. 1996. Synergistic interactions between XPC and p53 mutations in double-mutant mice: neural tube abnormalities and accelerated UV radiation-induced skin cancer. Curr. Biol. 6:1691-1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi, J.-H., A. Besaratinia, D.-H. Lee, C.-S. Lee, and G. P. Pfeifer. 2006. The role of DNA polymerase ι in UV mutational spectra. Mutat. Res. 599:58-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cleaver, J. E. 2005. Cancer in xeroderma pigmentosum and related disorders of DNA repair. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5:564-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Courdavault, S., C. Baudouin, M. Carveron, B. Canguilhem, A. Favier, J. Cadet, and T. Douki. 2005. Repair of the three main types of bipyrimidine DNA photoproducts in human keratinocytes exposed to UVB and UVA radiations. DNA Repair 4:836-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Courdavault, S., C. Baudouin, S. Sauvagio, S. Mouret, S. Candéias, M. Carveron, A. Favier, J. Cadet, and T. Douki. 2004. Unrepaired cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers do not prevent proliferation of UV-B-irradiated cultured human fibroblasts. Photochem. Photobiol. 79:145-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delbos, F., A. De Smet., A. Faili, S. Aoufouchi, J. C. Weill, and C. A. Reynaud. 2005. Contribution of DNA polymerase η to immunoglobulin gene hypermutation in the mouse. J. Exp. Med. 201:1191-1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D'Errico, M., M. Teson, A. Calcagnile, L. Proietti De Santis, O. Nikaido, E. Botta, G. Zambruno, M. Stefanini, and E. Dogliotti. 2003. Apoptosis and efficient repair of DNA damage protect human keratinocytes against UVB. Cell Death Differ. 10:754-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Vries, A., C. Th. M. van Oostrom, F. M. A. Hofhuis, P. M. Dortant, R. J. W. Berg, F. R. de Gruijl, P. W. Wester, C. F. van Kreijl, P. J. A. Capel, H. van Steeg, and S. J. Verbeek. 1995. Increased susceptibility to ultraviolet-B and carcinogens of mice lacking the DNA excision repair gene XPA. Nature 377:169-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diaz, M., and C. Lawrence. 2005. An update on the role of translesion synthesis DNA polymerases in Ig hypermutation. Trends Immunol. 26:215-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedberg, E. C., A. R. Lehmann, and R. P. P. Fuchs. 2005. Trading places: how do DNA polymerases switch during translesion DNA synthesis? Mol. Cell 18:499-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedberg, E. C., and L. B. Meira. 2006. Database of mouse strains carrying targeted mutations in genes affecting biological responses to DNA damage, version 7. DNA Repair 5:189-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibbs, P. E. M., W. G. McGregor, V. M. Maher, P. Nisson, and C. W. Lawrence. 1998. A human homolog of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae REV3 gene, which encodes the catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase ζ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:6876-6880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibbs, P. E. M., X.-D. Wang, Z. Li, T. P. McManus, W. G. McGregor, C. W. Lawrence, and V. M. Maher. 2000. The function of the human homolog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae REV1 is required for mutagenesis induced by UV light. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:4186-4191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanawalt, P. C., P. K. Cooper, A. K. Ganesan, and C. A. Smith. 1979. DNA repair in bacteria and mammalian cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 48:783-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higashi, Y., M. Maruhashi, L. Nelles, T. van de Putte, K. Vershueren, T. Miyoshi, A. Yoshimoto, H. Kondoh, and D. Huylebroeck. 2002. Generation of the floxed allele of the SIP1 (Smad-interacting protein 1) gene for Cre-mediated conditional knockout in the mouse. Genetics 32:82-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Itoh, T., S. Linn, R. Kamide, H. Tokushige, N. Katori, Y. Hosaka, and M. Yamaizumi. 2000. Xeroderma pigmentosum variant heterozygotes show reduced levels of recovery of replicative DNA synthesis in the presence of caffeine after ultraviolet irradiation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 115:981-985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jans, J., W. Schul, Y.-G. Sert, Y. Rijksen, H. Rebel, A. P. M. Eker, S. Nakajima, H. van Steeg, F. R. de Gruijl, A. Yasui, J. H. Hoeijmakers, and G. T. van der Horst. 2005. Powerful skin cancer protection by a CPD-photolyase transgenic. Curr. Biol. 15:105-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jansen, J. G., P. Langerak, A. Tsaalbi-Shtylik, P. van den Berk, H. Jacobs, and N. de Wind. 2006. Strand-biased defect in C/G transversions in hypermutating immunoglobulin genes in Rev1-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 203:319-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jansen, J. G., A. Tsaalbi-Shtylik, P. Langerak, F. Calléja, C. M. Meijers, H. Jacobes, and N. de Wind. 2005. The BRCT domain of mammalian Rev1 is involved in regulating DNA translesion synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:356-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson, R. E., M. T. Washington, L. Haracska, S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 2001. Eukaryotic polymerase ι and ζ act sequentially to bypass DNA lesions. Nature 406:1015-1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson, R. E., M. T. Washington, S. Prakash, and L. Prakash. 2000. Fidelity of human DNA polymerase η. J. Biol. Chem. 275:7447-7450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaufmann, W. K., T. P. Heffernan, L. M. Beaulieu, S. Doherty, A. R. Frank, Y. Zhou, M. F. Bryant, T. Zhou, D. D. Luche, N. Nikolaishvili-Feinberg, D. A. Simpson, and M. Cordeiro-Stone. 2003. Caffeine and human DNA metabolism: the magic and the mystery. Mutat. Res. 532:85-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kusumoto, R., C. Masutani, K. Sugasawa, S. Iwai, M. Araki, A. Uchida, T. Mizukoshi, and F. Hanaoka. 2001. Diversity of the damage recognition step in the global genomic nucleotide excision repair in vitro. Mutat. Res. 485:219-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee, G.-H., and H. Matsushita. 2005. Genetic linkage between Pol ι deficiency and increased susceptibility to lung tumors in mice. Cancer Sci. 96:256-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee, G.-H., H. Nishimori, Y. Sasaki, H. Matsushita, T. Kitagawa, and T. Tokino. 2003. Analysis of lung tumorigenesis in chimeric mice indicates the Pulmonary adenoma resistance 2 (Par2) locus to operate in the tumor-initiation stage in a cell-autonomous manner: detection of polymorphisms in the Polι gene as a candidate for Par2. Oncogene 22:2374-2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee, H.-D., and G. P. Pfeifer. 2003. Deamination of 5-methylcytosines within cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers is an important component of UVB mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 278:10314-10321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lehmann, A. R., S. Kirk-Bell, C. F. Arlett, M. C. Paterson, P. H. M. Lohman, E. A. de Weerd-Kastlelein, and D. Bootsma. 1975. Xeroderma pigmentosum cells with normal levels of excision repair have a defect in DNA synthesis after UV-irradiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 72:219-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li, Z., H. Zhang, T. P. McManus, J. J. McCormick, C. W. Lawrence, and V. M. Maher. 2002. hREV3 is essential for error-prone translesion synthesis past UV or benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide-induced DNA lesions in human fibroblasts. Mutat. Res. 510:71-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin, Q., A. B. Clark, S. D. McCulloch, T. Yuan, R. T. Bronson, T. A. Kunkel, and R. Kucherlapati. 2006. Increased susceptibility to UV-induced skin carcinogenesis in polymerase η-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 66:87-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ling, H., F. Boudsocq, R. Woodgate, and W. Yang. 2001. Crystal structure of a Y-family DNA polymerase in action: a mechanism for error-prone and lesion-bypass replication. Cell 107:91-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martomo, S. A., W. Y. William, R. P. Wersto, T. Ohkumo, Y. Kondo, M. Yokoi, C. Masutani, F. Hanaoka, and P. J. Gearhart. 2005. Different mutation signatures in DNA polymerase η- and MSH6-deficient mice suggest separate roles in antibody diversification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:8656-8661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martomo, S. A., W. W. Yang, A. Vaisman, A. Maas, M. Yokoi, J. H. Hoeijmakers, F. Hanaoka, R. Woodgate, and P. J. Gearhart. 2006. Normal hypermutation in antibody genes from congenic mice defective for DNA polymerase ι. DNA Repair 5:392-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Masuda, K., R. Ouchida, A. Takeuchi, T. Saito, H. Koseki, K. Kawamura, M. Tagawa, T. Tokuhisa, T. Azuma, and J. O. Wang. 2005. DNA polymerase θ contributes to the generation of C/G mutations during somatic hypermutation of Ig genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:13986-13991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Masutani, C., M. Araki, A. Yamada, R. Kusumoto, T. Nogimori, T. Maekawa, S. Iwai, and F. Hanaoka. 1999. Xeroderma pigmentosum variant (XP-V) correcting protein from HeLa cells has a thymine dimer bypass DNA polymerase activity. EMBO J. 18:3491-3501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Masutani, C., R. Kusumoto, S. Iwai, and F. Hanaoka. 2000. Mechanisms of accurate translesion synthesis by human DNA polymerase η. EMBO J. 19:3100-3109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Masutani, C., R. Kusumoto, A. Yamada, N. Dohmae, M. Yokoi, M. Yuasa, M. Araki, S. Iwai, K. Takio, and F. Hanaoka. 1999. The XPV (xeroderma pigmentosum variant) gene encodes human DNA polymerase η. Nature 399:700-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsumoto, T., J. Jiang, K. Kiguchi, L. Ruffino, S. Carbajal, L. Beltrán, D. K. Bol, M. P. Rosenberg, and J. DiGiovanni. 2003. Targeted expression of c-Src in epidermal basal cells leads to enhanced skin tumor promotion, malignant progression, and metastasis. Cancer Res. 63:4819-4828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McDonald, J. P., E. G. Frank, B. S. Plosky, I. B. Rogozin, C. Masutani, F. Hanaoka, R. Woodgate, and P. J. Gearhart. 2003. 129-derived strains of mice are deficient in DNA polymerase ι and have normal immunoglobulin hypermutation. J. Exp. Med. 198:635-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitchell, D. L., J. E. Cleaver, and J. H. Epstein. 1990. Repair of pyrimidine(6-4)pyrimidone photoproducts in mouse skin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 95:55-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagy, A., J. Rossant, R. Nagy, W. Abramow-Newerly, and J. C. Roder. 1993. Derivation of completely cell culture-derived mice from early-passage embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:8424-8428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakane, H., S. Takeuchi, S. Yuba, M. Saijo, Y. Nakatsu, H. Murai, Y. Nakatsuru, T. Ishikawa, S. Hirota, Y. Kitamura, Y. Kato, Y. Tsunoda, H. Miyauchi, T. Horio, T. Tokunaga, T. Matsunaga, O. Nikaido, Y. Nishimune, Y. Okada, and K. Tanaka. 1995. High incidence of ultraviolet-B- or chemical-carcinogen-induced skin tumors in mice lacking the xeroderma pigmentosum group A gene. Nature 377:165-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peckham, J. C., and K. Heider. 1999. Skin and subcutis, p. 555-612. In R. R. Maronpot (ed.), Pathology of the mouse: reference and atlas. Cache River Press, Vienna, Austria.

- 50.Peng, W., and B. R. Shaw. 1996. Accelerated deamination of cytosine residues in UV-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers leads to CC→TT transitions. Biochemistry 35:10172-10181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qin, X., S. Zhang, H. Oda, Y. Nakatsuru, S. Shimizu, Y. Yamazaki, O. Nikaido, and T. Ishikawa. 1995. Quantitative detection of ultraviolet light-induced photoproducts in mouse skin by immunohistochemistry. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 86:1041-1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ruven, H. J., C. M. Seelen, P. H. Lohman, H. van Kranen, A. A. van Zeeland, and L. H. Mullenders. 1994. Strand-specific removal of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers from the p53 gene in the epidermis of UVB-irradiated hairless mice. Oncogene 9:3427-3432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sands, A. T., A. Abuin, A. Sanchez, C. J. Conti, and A. Bradley. 1995. High susceptibility to ultraviolet-induced carcinogenesis in mice lacking XPC. Nature 377:162-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seki, M., P. J. Gearhart, and R. D. Wood. 2005. DNA polymerases and somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes. EMBO Rep. 6:1143-1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shimizu, T., T. Azuma, M. Ishiguro, N. Kanjo, A. Yamada, and H. Ohmori. 2005. Normal immunoglobulin gene somatic hypermutation in Polκ-Polι double-deficient mice. Immunology Lett. 98:259-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Silvian, L. F., E. A. Toth, P. Pham, M. F. Goodman, and T. Ellenberger. 2001. Crystal structure of a DinB family error-prone DNA polymerase from Sulfolobus solfataricus. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8:984-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sugasawa, K., T. Okamoto, Y. Shimizu, C. Masutani, S. Iwai, and F. Hanaoka. 2001. A multiple damage recognition mechanism for global genomic nucleotide excision repair. Genes Dev. 15:507-521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takasawa, K., C. Masutani, F. Hanaoka, and S. Iwai. 2004. Chemical synthesis and translesion replication of a cis-syn cyclobutane thymine-uracil dimer. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1738-1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tessman, I., A. M. Kennedy, and S. K. Liu. 1994. Unusual kinetics of uracil formation in single and double-stranded DNA by deamination of cytosine in cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers. J. Mol. Biol. 235:807-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tissier, A., E. G. Frank, J. P. McDonald, S. Iwai, F. Hanaoka, and R. Woodgate. 2000. Misinsertion and bypass of thymine-thymine dimers by human DNA polymerase ι. EMBO J. 19:5259-5266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trincao, J., R. E. Johnson, C. R. Escalante, S. Prakash, L. Prakash, and A. K. Aggarwal. 2001. Structure of the catalytic core of S. cerevisiae DNA polymerase η: implications for translesion DNA synthesis. Mol. Cell 8:417-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tu, Y., R. Dammann, and G. P. Pfeifer. 1998. Sequence and time-dependent deamination of cytosine bases in UVB-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers in vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 284:297-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vaisman, A., E. G. Frank, S. Iwai, E. Ohashi, H. Ohmori, F. Hanaoka, and R. Woodgate. 2003. Sequence context-dependent replication of DNA templates containing UV-induced lesions by human DNA polymerase ι. DNA Repair 2:991-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vaisman, A., E. K. Frank, J. P. McDonald, A. Tissier, and R. Woodgate. 2002. Polι-dependent lesion bypass in vitro. Mutat. Res. 510:9-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vaisman, A., K. Takasawa, S. Iwai, and R. Woodgate. 2006. DNA polymerase ι-dependent translesion replication of uracil containing cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers. DNA Repair 5:210-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vaisman, A., and R. Woodgate. 2001. Unique misinsertion specificity of polι may decrease the mutagenic potential of deaminated cytosines. EMBO J. 20:6520-6529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van der Horst, G. T. J., L. Meira, T. G. M. F. Gorgels, J. de Wit, S. Velasco-Miguel, J. A. Richardson, Y. Kamp, M. P. G. Vreeswijk, B. Smit, D. Bootsma, J. H. J. Hoeijmakers, and E. C. Friedberg. 2002. UVB radiation-induced cancer predisposiotion in Cockayne syndrome group A (Csa) mutant mice. DNA Repair 1:143-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang, M., T. R. Devereux, H. G. Vikis, S. D. McCulloch, W. Holliday, C. Anna, Y. Wang, K. Bebenek, T. A. Kunkel, K. Guan, and M. You. 2004. Pol ι is a candidate for the mouse pulmonary adenoma resistance 2 locus, a major modifier of chemically induced lung neoplasia. Cancer Res. 64:1924-1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ward, J. M., M. R. Anver, J. F. Mahler, and D. E. Devor-Henneman. 2000. Pathology of mice commonly used in genetic engineering (C57BL/6; 129; B6, 129; and FVB/N), p. 161-179. In J. M. Ward, J. F. Mahler, R. R. Maronpot, and J. P. Sundberg (ed.), Pathology of genetically engineered mice. Iowa State University Press, Ames.

- 70.Yamada, A., C. Masutani, S. Iwai, and F. Hanaoka. 2000. Complementation of defective translesion synthesis and UV light sensitivity in xeroderma pigmentosum variant cells by human and mouse DNA polymerase η. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:2473-2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yamazaki, F., H. Okamoto, Y. Matsumura, K. Tanaka, K. Kunisada, and T. Horio. 2005. Development of a new mouse model (xeroderma pigmentosum A-deficient, stem cell factor-transgenic) of ultraviolet B-induced melanoma. J. Investig. Dermatol. 125:521-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yanagawa, Y., T. Kobayashi., M. Ohnishi, T. Kobayashi, S. Tamura, T. Tsuzuki, M. Sanbo, T. Yagi, F. Tashiro, and J. Miyazaki. 1999. Enrichment and efficient screening of ES cells containing a targeted mutation: the use of DT-A gene with the polyadenylation signal as a negative selection marker. Transgenic Res. 8:215-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.You, Y.-H., D.-H. Lee, J.-H. Yoon, S. Nakajima, A. Yasui, and G. P. Pfeifer. 2001. Cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers are responsible for the vast majority of mutations induced by UVB irradiation in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276:44688-44694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yuasa, M., C. Masutani, T. Eki, and F. Hanaoka. 2000. Genomic structure, chromosomal localization and identification of mutations in the xeroderma pigmentosum variant (XPV) gene. Oncogene 19:4721-4728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zan, H., N. Shima, Z. Xu, A. Al-Qahtani, A. J. Evinger III, Y. Zhong, J. C. Schumenti, and P. Casali. 2005. The translesion DNA polymerase θ plays a dominant role in immunoglobulin gene somatic hypermutation. EMBO J. 24:3757-3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang, Y., F. Yuan, X. Wu, J.-S. Taylor, and Z. Wang. 2001. Response of human DNA polymerase ι to DNA lesions. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:928-935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]