Abstract

Cutl1/CCAAT displacement protein (CDP) is a transcriptional repressor of mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV), a betaretrovirus that is a paradigm for mammary-specific gene regulation. Virgin mammary glands have high levels of full-length CDP (200 kDa) that binds to negative regulatory elements (NREs) to repress MMTV transcription. During late pregnancy, full-length CDP levels decline, and a 150-kDa form of CDP (CDP150) appears concomitantly with a decline in DNA-binding activity for the MMTV NREs and an increase in viral transcripts. Developmental regulation of CDP was recapitulated in the normal mammary epithelial line, SCp2. Western blotting of tissue and SCp2 nuclear extracts confirmed that CDP150 lacks the C terminus. Transfection of tagged full-length and mutant cDNAs into SCp2 cells and use of a cysteine protease inhibitor demonstrated that CDP is proteolytically processed within the homeodomain to remove the C terminus during differentiation. Mixing of virgin and lactating mammary extracts or transfection of mutant CDP cDNAs missing the homeodomain into cells containing full-length CDP also abrogated NRE binding. Loss of DNA binding correlated with increased expression of MMTV and other mammary-specific genes, indicating that CDP150 is a developmentally induced dominant-negative protein. Thus, a novel posttranslational process controls Cutl1/CDP activity and gene expression in the mammary gland.

CCAAT displacement protein (CDP) belongs to a family of transcription factors that is involved in the regulation of cellular proliferation and differentiation (36). Members of this gene family include Drosophila melanogaster cut, human CUTL1, murine Cut homeobox (Cux-1) or Cut-like 1 (Cutl1), canine Cut-like homeobox (Clox), and rat CDP2 (1, 15, 42, 47, 51). More recently, a second Cutl gene, Cux-2 or Cutl2, was identified in mice and chickens (38, 45). Unlike Cutl1, which is found in most tissues, Cutl2 is expressed primarily in the nervous system (38). Proteins encoded by these genes contain four highly conserved DNA-binding domains, a homeodomain (HD) and three conserved domains of 70 amino acids known as cut repeats (CR1, -2, and 3), which exhibit distinct DNA-binding specificities and kinetics (2, 36). Cutl1/CDP also contains a coiled-coil leucine zipper (LZ) near the amino terminus and two active repression domains near the C terminus (29). Current data suggest that CDP binds to a wide range of DNA sequences to regulate gene expression (36).

Genetic studies of the Drosophila cut gene have revealed an important role in determining cell type specificity in several tissues (5, 6, 36), and similar conclusions have been obtained with mice and chickens (45, 46). Experiments using Cutl1 knockout mice showed organ-specific phenotypes, including curly whiskers, growth retardation, altered hair follicle morphogenesis, delayed differentiation of lung epithelia, male infertility, and excess production of myeloid cells (13, 28, 44). Further, mice expressing a Cutl1 variant missing CR1 (ΔCR1) had a defect in milk composition (46). In contrast, Cutl1 overexpression in transgenic mice caused multiorgan hyperplasia and organomegaly (22).

Cutl1/CDP is a transcriptional repressor of multiple cellular genes, including gp91-phox, c-myc, T-cell receptor β chain, CD8, and immunoglobulin heavy chain (4, 12, 20, 24, 36, 49), as well as viral genes, including mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) and human papillomavirus (37, 53). Multiple studies indicate that CDP is expressed at high levels in undifferentiated cells, whereas CDP-mediated repression declines during differentiation (36). Kidney-specific Cutl1 expression is inversely related to the degree of cellular differentiation (48), and DNA-binding activity is down-regulated during myeloid and B-cell development (21, 49). In addition, we previously have shown that CDP negatively regulates transcription of multiple genes that are expressed in differentiated mammary glands (54). These results indicate that CDP is a transcriptional repressor of genes whose expression is highest during the end stages of differentiation. Furthermore, Cutl1/CDP appears to participate in cell migratory behavior and has been associated with breast cancer progression (31).

MMTV is a retrovirus that primarily induces mammary carcinomas, and the viral major promoter is a paradigm for mammary-specific and hormone-regulated expression (35). Multiple transcriptional controls suppress MMTV expression at early stages of mammary development (27, 52, 53). However, viral mRNA levels increase during differentiation, and the highest levels of transcription occur during lactation, a time when virus is transmitted from mothers to offspring in the milk (54). We previously have shown that CDP is a repressor of MMTV expression (52, 53). CDP binding to viral negative regulatory elements (NREs) in the MMTV long terminal repeats (LTRs) is maximal in virgin mammary gland, and this activity declines during mammary development (53). Interestingly, CDP itself is differentially regulated during mammary differentiation. Full-length CDP levels decline during mammary development, concurrent with the appearance of a novel 150-kDa protein and decreased binding to the MMTV NREs (53, 54). However, the mechanism of CDP-mediated MMTV regulation during mammary differentiation has not been demonstrated.

In the present study, we have investigated the mechanism of CDP regulation in the mammary gland. We have shown that the levels of full-length CDP decrease both in vivo and in cultured breast epithelial cells during differentiation, a period when MMTV transcription increases. Endogenous or exogenous full-length CDP protein (200 kDa) is proteolytically cleaved to generate a novel C-terminally truncated protein of 150 kDa with identical properties (here called CDP150), and this processing event is regulated during mammary differentiation. Interestingly, analysis of full-length CDP or deletion mutants indicated that both the HD and the C terminus are required for processing and that CDP150 acts as a dominant-negative protein on both the MMTV NREs and the β-casein promoter. Further, reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) confirmed that RNA levels of several mammary-specific genes increased after expression of a construct similar to CDP150. Together, these results revealed a novel mode of CDP-mediated regulation during mammary development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and SCp2 cell differentiation.

SCp2 normal mouse mammary epithelial cells were obtained from Mina Bissell (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, University of California) and grown as previously described (10). To induce differentiation, 5 × 105 cells were plated in 1 ml of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/F-12 medium containing 5 μg/ml insulin and 1 μg/ml hydrocortisone (Sigma) into 24-well tissue culture dishes precoated with basement membrane gels and incubated overnight at 37°C. For preparation of reconstituted basement membrane gels, 140 μl of Matrigel (BD Biosciences) was spread evenly onto each well at 4°C and subsequently allowed to solidify in a humidified incubator at 37°C for 30 min before cell addition. The next day, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the medium was replaced with 1 ml of differentiation medium (DMEM/F-12 containing 5 μg/ml insulin, 1 μg/ml hydrocortisone, and 3 μg/ml prolactin) and incubated for 4 days with medium changes every other day. For protease inhibitor studies, cells were incubated under various differentiation conditions in the presence or absence of 50 μM of E64d (Calbiochem). The medium was changed every other day for 6 days. Cells were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting. The differentiated cells were washed with PBS, then resuspended in Matrisperse cell recovery solution (BD Biosciences), and incubated on ice for 2 to 3 h to remove the extracellular matrix (ECM). After complete release of cells from the gel, the cells were centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The cell pellets were washed in PBS, and nuclear or whole-cell extracts were prepared for Western blot analysis and electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs).

Plasmid constructions.

The plasmid pMTV-LUC (also called pLC-LUC or pC3H-LUC) contains the C3H MMTV LTR sequence upstream of firefly luciferase as described previously (43, 53). The full-length Cutl1/CDP cDNA clone used here originally was obtained from Ellis Neufeld (24) and begins at the first in-frame ATG at position 44 of exon 1b of the Cutl1 gene. The full-length CDP gene was cloned into pCMV-Tag2A at the EcoRI and EcoRV sites (FLAG-CDP). This N-terminally FLAG-tagged CDP vector was C-terminally hemagglutinin (HA) tagged by Patrick Hearing (14). The construct FLAG-ΔCR23HD, lacking the CR2, CR3, and HD, was prepared by partial BamHI digestion of FLAG-CDP. The 7,683-bp fragment was recovered from the gel, and the ends were ligated. The FLAG-ΔC plasmid, which lacks the C-terminal domain of CDP, was constructed by partial BamHI digestion of FLAG-CDP followed by blunting the ends and ligation, resulting in deletion of the C terminus at bp 3936. The HA tag sequence was added to the C-terminal end of FLAG-ΔC by PCR using the following primers: CDP HindIII+ (5′ ATC CTC ACC CCC AAG CTT CTG TCC ACC 3′) and CDP-ΔCHA- (5′ CTA GCT AGC TCA CAG GCT GGC ATA GTC AGG CAC GTC ATA AGG ATA GCT GAT CCG AGA 3′). The PCR product was gel purified and cloned into the HindIII and NheI sites of the CDP expression vector. FLAG-ΔHD-HA, which has an internal deletion of the HD, was prepared by recombinant PCR using the following primer pairs: CDP HindIII+ and CDPin- (5′ CTC AAT GAA CAG GGG CTG GCT GTC ACT GAC TGA 3′); CDPin+ (5′ GAC AGC CAG CCC CTG TTC ATT GAG GAA ATT CAG 3′) and CDPHANheI- (5′ CTA GCT AGC TCA CAG GCT GGC AT 3′). The PCR products were digested with HindIII and NheI and cloned into the HindIII and NheI sites of the CDP vector. The FLAG-ΔHD15C vector was made by using the following primers: CDP HindIII+ and CDP-ΔHD15- (5′ CTA GCT AGC TCA GCT TGT TTT CAG GTT 3′). The PCR product was gel purified using spin columns (QIAGEN) and digested with HindIII and NheI and cloned into the CDP expression vector digested with HindIII and NheI. All PCRs were performed using the Expand Long Template PCR system (Roche). The ΔLZHD15C mutant was constructed by recombinant PCR to delete the leucine zipper region (bp 1040 to 1277); the fragment was cloned into the EcoR1 and EcoRV sites of FLAG-CDP. The construct was then modified as described for FLAG-ΔHD15C. The β-casein-LUC plasmid was constructed by PCR amplification of a region from bp −1 to −330 upstream of the β-casein transcription start site. The following primers containing a HindIII restriction site were used: β-casein1 (5′ CCC AAG CTT GTC CTA TCA GAC TCT GTG ACC GTA 3′) and β-casein331 (5′ CCC AAG CTT TTA AAG CCC CCC ACT AGG 3′). The PCR product was gel purified, digested with HindIII, and cloned into the HindIII site of p19LUC containing the firefly luciferase gene. The correct orientation of the insert was confirmed by sequencing.

Transient transfections and luciferase assays.

SCp2 cells were transfected with DMRIE-C reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Transfections were performed with either full-length or CDP deletion mutant constructs followed by incubation of cells with or without differentiation medium and ECM. After 4 days of differentiation, the transfected cells were resuspended in Matrisperse cell recovery solution and then used for preparation of nuclear extracts. For luciferase assays, 5 × 105 SCp2 cells were seeded in a six-well plate in 2 ml of DMEM/F-12 growth medium. For each transfection, pMTV-LUC and different amounts of full-length and truncated CDP expression vectors were added to 1 ml of DMEM/F-12 without serum containing 12 μl of DMRIE-C reagent and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The cells were washed with DMEM/F-12 without serum, and the DNA solution was incubated with the cells for 6 h at 37°C. Subsequently, 1 ml of complete medium containing twice the normal concentration of serum was added without removing the DNA-containing medium, and the cells were incubated at 37°C in a CO2 incubator for 48 h. The cells were assayed for luciferase activity using the Dual Luciferase detection kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transfections were expressed as relative values per 100 μg protein.

Preparation of nuclear extracts and Western analysis.

Nuclear extracts for EMSAs were prepared essentially as described by Liu et al. (27). Mammary tissue extracts were prepared from normal BALB/cJ mice (Jackson Labs) or Sprague-Dawley rats as described previously (54). Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts from transfected SCp2 cells for Western analysis were prepared using the NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents kit (Pierce Biotechnology). Whole-cell lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.8], 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate), and the protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent. Protein extracts were subjected to electrophoresis on 6% polyacrylamide gels prior to Western blotting, as described elsewhere (54). Binding of the secondary antibody was detected using the Western blotting Lightning ECL detection system (Perkin-Elmer). The N-terminal CDP-specific antibody was kindly provided by Alain Nepveu (McGill University, Montreal, Canada). The FLAG and HA antibodies were obtained from Stratagene and Roche, respectively. The C-20 polyclonal antibody specific for the C-terminal 20 amino acids of Cutl1/CDP was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibodies specific for the C-terminal region of CDP (CR2-Cterm) have been described previously (27).

EMSAs and antibody ablation assays.

EMSAs were performed as described by Liu et al. (26, 27) using the pNRE4 probe (27). Conditions for Sp1 binding have been described elsewhere (53). The 145-bp β-casein probe spanning the CDP-binding sites predicted by the TRANSFAC software was obtained by PCR using the following primers: β-casein 4606 (5′ CCG GAA TTC TTG GCT GGA GGA ACA TGT AGT TGT T 3′) and β-casein 4750 (5′ CCC AAG CTT TTA GAA AAT GGT TTC TTT CTA TT 3′). The introduced HindIII and EcoRI sites are shown in bold. The PCR product was gel purified, digested with EcoRI and HindIII, and cloned into pcDNA3 (Invitrogen). Purified plasmid DNA from pNRE4 was digested with EcoRI and HindIII (pNRE4) to give 5′ overhanging ends, and the inserts were isolated on polyacrylamide gels. Fragments were end labeled with Sequenase (version 2.0; USB Corp.), and 2.5 fmol was incubated with nuclear extracts and analyzed on 4% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels as previously described (54). One μl (1:10 dilution) of rabbit anti-CDP (CR2-Cterm), mouse anti-FLAG or preimmune serum was used for antibody ablation experiments as described previously (27).

RT-PCRs.

RNA extraction methods, conditions for RT-PCRs, and some primer sequences have been described previously (54). Primer pairs used to test the expression of different DNA-binding domains of CDP were as follows: CR1 (5′ TGC CAT CCG CTC CAT CCT ACA 3′ and 5′ GCT GGA ACT CAT TGG GGA CT 3′); CR2/CR3 (5′ AGC AGT ACG AGG TCT ACA TG 3′ and 5′ GCC CAG CTC TCC ATT CAG 3′); CR3/HD (5′ TGC CTC TCT CTG GAC ACT CA 3′ and 5′ GAG TCG CTG GCA CCA GCC TG 3′).

RESULTS

A novel C-terminally truncated form of CDP that lacks DNA-binding activity for the MMTV NREs appears during differentiation of mammary tissues and cultured cells.

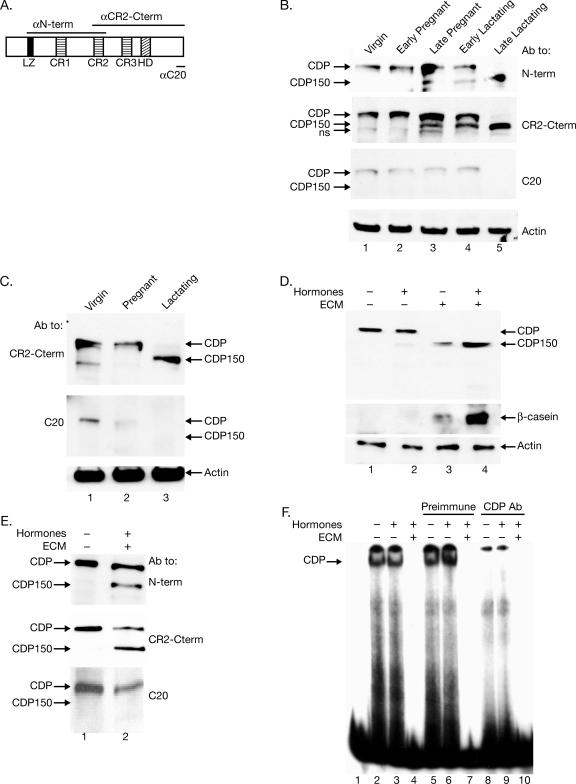

We have shown that full-length CDP (200 kDa) levels decline during mammary gland development, and a 150-kDa CDP form appears in lactating mammary glands (53). To further study CDP150, nuclear extracts from murine breast tissues at different stages of development were subjected to Western blotting with antibodies specific for different CDP regions (Fig. 1A). Consistent with our previous data (53), full-length CDP levels are highest in virgin mammary glands and lowest during lactation, whereas CDP150 appears during late pregnancy and is maximal during lactation. Antibodies to the N terminus or CR2-Cterm detected both full-length and CDP150 isoforms (Fig. 1B). However, antibodies specific for the C-terminal 20 amino acids (anti-C-20) detected full-length CDP but not CDP150 (lanes 3 to 5), indicating that the truncated CDP found in the late stages of mammary gland development lacks the C terminus. Similar results have been obtained using extracts from rat mammary tissues (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

A C-terminally truncated CDP appears during mammary cell differentiation in vivo and in culture. (A) Diagram of CDP-specific antibodies used for Western blotting. The N-terminal antibody (αN-term) recognizes the CDP region from the leucine zipper through CR2. The CR2-Cterm antibody (αCR2-Cterm) recognizes the CDP region from CR2 through the C terminus. The C-20 antibody (αC20) was prepared against the C-terminal 20 amino acids. (B) A C-terminally truncated CDP appears during late pregnancy. Equal amounts of nuclear extracts (75 μg) from tissues pooled from several animals were subjected to Western blotting with the indicated antibody (Ab). A nonspecific band (ns) was detected with the CR2-Cterm-specific antibody. Extracts were prepared at the following times: early pregnancy (7 days), late pregnancy (18 days), early lactation (2 days), and late lactation (5 days). (C) A C-terminally truncated CDP appears during lactation in rat mammary glands. Equal amounts of nuclear extracts (60 μg) were prepared and used for Western blots, which were incubated with the indicated antibodies. (D) A novel truncated form of CDP appears during mammary cell differentiation. SCp2 cells were plated on tissue culture dishes with or without ECM for 6 days in the presence or absence of lactogenic hormones to induce mammary cell differentiation. Equal amounts (25 μg) of nuclear extracts were analyzed by Western blotting using CDP-specific antibody (upper panel) or β-casein antibody (middle panel) as a marker for differentiation. Actin was used as a loading control (lower panel). (E) A C-terminally truncated CDP isoform appears during differentiation of SCp2 mammary cells in culture. Cells were plated in the absence or presence of hormones and ECM for 4 days. Nuclear extracts (25 μg) were subjected to Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. (F) The DNA-binding activity of CDP declines during mammary differentiation. Nuclear extracts were prepared from untreated SCp2 cells or cells treated with hormones with or without ECM for 6 days. Extracts (5 μg) were incubated in the presence or absence of CDP-specific or preimmune serum prior to incubation with a radiolabeled MMTV pNRE4 probe. Lane 1 shows a reaction without nuclear extract.

Because some molecular changes are difficult to characterize in whole mammary gland, differentiation of mammary epithelial cells has been recapitulated in tissue culture. SCp2 cells are derived from normal mouse mammary epithelium and differentiate to produce milk proteins, e.g., β-casein, in the presence of lactogenic hormones (prolactin, hydrocortisone, and insulin) and ECM (Matrigel) (10). To examine CDP levels during differentiation, SCp2 cells were cultured in the presence of either lactogenic hormones, ECM, or both. After 6 days, cells were harvested, and lysates were subjected to Western blotting using CDP-specific antibody (anti-CR2-Cterm). Full-length CDP (200 kDa) was detected in untreated SCp2 cells (Fig. 1D, lane 1). However, CDP150 was detectable when SCp2 cells were treated with hormones and ECM or ECM alone (Fig. 1D, lanes 3 and 4). The appearance of the shorter CDP form was dependent on the differentiation status of the mammary cells, which was confirmed by the presence or absence of β-casein. In agreement with results obtained with tissue extracts, additional Western blotting experiments indicated that the CDP150 form in differentiated SCp2 cells was detected by the antibodies specific for the N-terminal region or CR2-Cterm, but not by anti-C-20 (Fig. 1E). These data indicate that CDP150 is a C-terminally truncated form of Cutl1/CDP.

To examine the DNA-binding activities of CDP and CDP150, nuclear extracts were prepared from differentiated and undifferentiated SCp2 cells and analyzed by EMSA using a promoter-proximal NRE (pNRE) probe. CDP-binding activity to the pNRE within the MMTV LTR was detected in untreated SCp2 cells or cells treated with hormones alone (Fig. 1F, lanes 2 and 3); binding was abolished by CDP-specific, but not preimmune, sera (compare lanes 6 and 9). This activity disappeared following differentiation in the presence of ECM, concurrent with the loss of full-length CDP (Fig. 1F, lane 4). Incubation of the same extracts with Sp1 probe confirmed the integrity of the SCp2 nuclear extracts (data not shown), in agreement with previous data using tissue extracts (53). These results support our previously published data obtained with mammary tissues from different developmental stages (53) and validated this in vitro system for studying CDP regulation during mammary differentiation.

Loss of endogenous full-length CDP during mammary differentiation relieves MMTV transcriptional repression.

Previous studies have shown that CDP overexpression suppresses MMTV LTR-reporter activity in cultured cells (52, 53), and mutations within the LTR that inhibit CDP binding also increase MMTV transcription (52, 54). Thus, loss of full-length CDP during differentiation of SCp2 cells should elevate MMTV transcription. To verify this, the effect of cellular differentiation on MMTV-LTR-driven luciferase reporter gene expression (Fig. 2A) was determined in transient-transfection assays.

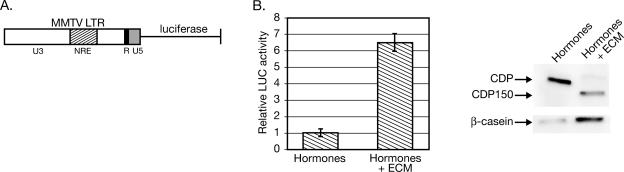

FIG. 2.

Appearance of CDP150 during differentiation correlates with increased transcription from the MMTV LTR. (A) Structure of the MMTV LTR-reporter construct used for transient-transfection assays. (B) Increased MMTV transcription during mammary differentiation correlates with the appearance of CDP150. SCp2 cells were transiently transfected with an MMTV LTR-firefly luciferase reporter and plated without or with ECM in the presence of lactogenic hormones to induce differentiation. After 4 days of treatment, cells were used to prepare extracts for luciferase assays and Western blotting. Firefly luciferase values obtained from cells grown in lactogenic hormones alone were assigned a value of 1. The means and standard deviations of three independent transfections are indicated. The Western blots were incubated with CDP- or β-casein-specific antibodies (right panel).

As expected, the differentiated SCp2 cells exhibited a 6.5-fold increase in MMTV-LTR transcriptional activity compared to that observed in the undifferentiated cells (Fig. 2B). Elevated viral transcription correlated with decreased levels of full-length CDP in the differentiated SCp2 cells, as confirmed by Western blotting (right-hand panel). Previous experiments have established that CDP does not affect expression of other reporter plasmids by using the Rous sarcoma virus or thymidine kinase promoters at the CDP levels used here (53). Furthermore, overexpression of an epitope-tagged CDP also repressed MMTV transcription in undifferentiated SCp2 cells (data not shown; see below). These results suggest that CDP regulates MMTV expression during mammary differentiation.

CDP is processed at the C terminus by a cysteine protease during mammary differentiation.

Full-length CDP is expressed in most undifferentiated tissues, although multiple isoforms of this protein also have been described (18, 25, 32). Proteolytic processing of CDP to a 110-kDa form during the G1/S transition plays an important role in the regulation of cell cycle progression (32). To study the mechanism of CDP down-regulation during mammary development, several possibilities were evaluated. First, an extensive cocktail of protease inhibitors was used during cell lysis to prevent proteolytic degradation during extract preparation. Mixing of nuclear extracts derived from virgin and lactating mammary tissues before or after homogenization revealed the presence of both full-length CDP and CDP150, suggesting that CDP was not being degraded during lysis and that both forms were in the nucleus (see below). Second, we examined whether CDP regulation occurred at the posttranscriptional level. No alterations in known CDP mRNA species were detected during mammary development using RT-PCR with RNAs extracted from virgin, pregnant, and lactating mammary glands and primers spanning the different DNA-binding domains (data not shown). Third, we determined whether CDP150 is generated by proteolytic cleavage of the full-length protein.

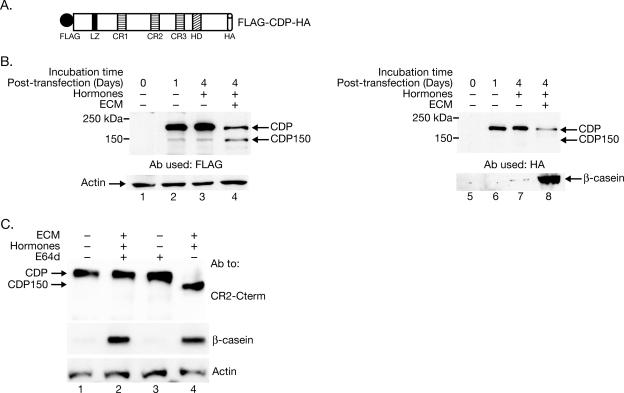

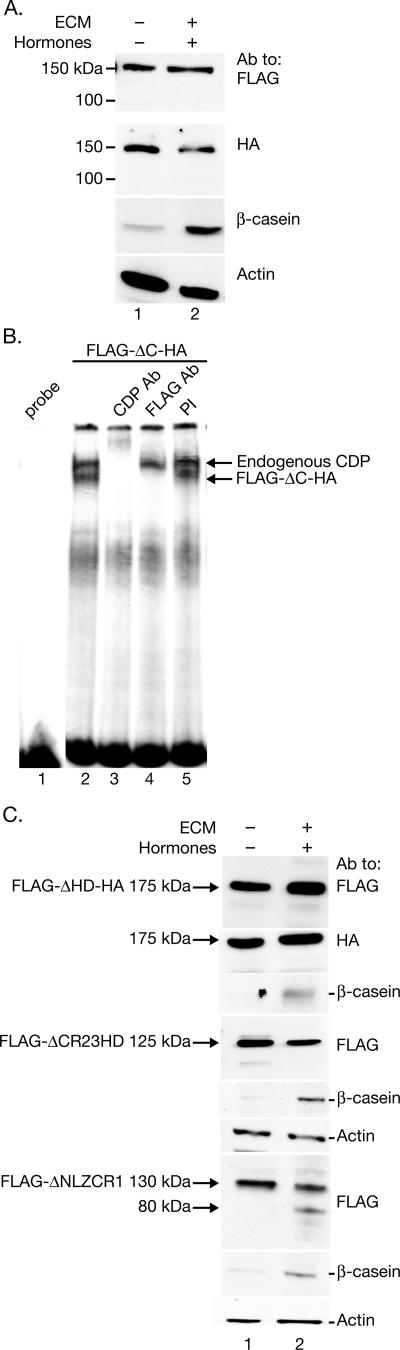

To evaluate this model, SCp2 cells were transfected with a vector encoding the full-length CDP cDNA carrying N-terminal FLAG and C-terminal HA tags (Fig. 3A). Transfected cells were plated with or without ECM in the presence of lactogenic hormones to determine whether one of the terminal tags would be lost during differentiation. After 4 days, cells were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting using FLAG- or HA-specific antibody. Cells harvested 24 h posttransfection were used to ensure that full-length CDP could be detected (Fig. 3B, lane 2). FLAG-specific antibody confirmed the presence of the N terminus in both CDP and CDP150 (Fig. 3B, lane 4). However, the HA-specific antibody detected full-length CDP, but not the 150-kDa form, in differentiated cells, consistent with CDP processing at the C terminus to form CDP150 (Fig. 3B, lane 8).

FIG. 3.

Full-length CDP loses a C-terminal tag during mammary differentiation. (A) Structure of the full-length tagged CDP (FLAG-CDP-HA) expressed in SCp2 mammary cells. FLAG, peptide tag; LZ, leucine zipper; CR, cut repeats; HD, homeodomain; HA, hemagglutinin peptide tag. (B) A C-terminal CDP tag is lost during mammary differentiation in culture. SCp2 cells were transiently transfected with a vector expressing FLAG-CDP-HA and plated on tissue culture dishes without (lane 3) or with (lane 4) ECM in the presence of hormones. Lysates prepared from untransfected cells are shown in lane 1. Cell lysates were prepared after 1 day (lane 2) or 4 days posttransfection and analyzed by Western blotting using either FLAG- or HA-specific antibodies (upper panels). The same lysates were analyzed using actin-specific antibody to control for protein loading or with β-casein-specific antibody as a marker for differentiation (lower panels). (C) The cysteine protease inhibitor E64d blocks CDP processing during mammary differentiation. SCp2 cells were plated on ECM with or without hormones in the presence or absence of E64d. Cells were harvested, and 30-μg aliquots of nuclear extracts were analyzed by Western blotting using specific antibodies.

To obtain further evidence for proteolytic processing of CDP during mammary differentiation, SCp2 cells were cultured with or without hormones and ECM in the presence of inhibitors for various proteases. Proteosome, cathepsin, calpain, and caspase inhibitors did not inhibit the appearance of CDP150, although some specific inhibitors could not be tested due to lack of cell permeability (data not shown). Interestingly, the appearance of the 110-kDa isoform of CDP in NIH 3T3 cells is blocked by the presence of 20 to 200 μM E64d (17), a membrane-permeable inhibitor that specifically affects cysteine proteases, including calpains and cathepsins (30). Culture of SCp2 mammary cells in the presence of 50 μM E64d blocked the appearance of CDP150 but did not cause significant toxicity as measured by the level of β-casein (Fig. 3C, compare lanes 2 and 4). Thus, the appearance of CDP150 in differentiating SCp2 cells transfected with cDNA expression vectors, which lack introns, and the failure of endogenous CDP150 to appear in the presence of a specific protease inhibitor support the proteolytic processing model.

CDP processing in mammary cells requires both the HD and the C terminus.

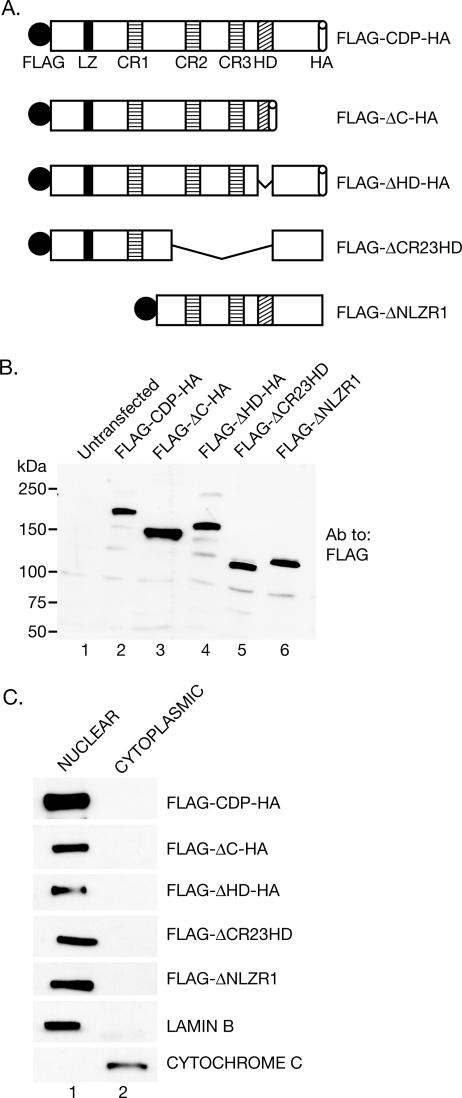

To map the sequences required for processing, a series of CDP expression vectors expressing tagged versions of the protein were generated (Fig. 4A). Expression of mutant proteins and their localization to the nucleus was confirmed (Fig. 4B and C). Since mutants lacking the N-terminal, middle, or C-terminal region each were detected in the nucleus, these results suggested that full-length CDP has at least two nuclear localization signals. Subsequently, each of the N-terminally FLAG-tagged CDP mutants was transfected into SCp2 cells, and the appearance of the truncated CDP forms was analyzed after differentiation by Western blotting using FLAG- or HA-specific antibody.

FIG. 4.

Tagged full-length and CDP deletion mutants are expressed in the nucleus of SCp2 mammary cells. (A) Schematic representation of tagged full-length and deleted versions of CDP. Construct names indicate the CDP domains that are deleted. (B) Equivalent expression of full-length CDP and deletion constructs. SCp2 cells were transfected with the full-length CDP or the various truncated CDP expression vectors, and cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with FLAG-specific antibody. (C) Nuclear localization of full-length and mutant CDPs. SCp2 cells were transfected with constructs expressing either full-length CDP or different deletion mutants and then subjected to cytoplasmic-nuclear fractionation. Fractions were subjected to Western blotting with FLAG-specific antibody to detect tagged CDPs. Use of antibodies for lamin B and cytochrome c served as a control for the fractionation protocol.

Since our previous data indicated that CDP150 is a C-terminally truncated form of CDP, we used a mutant lacking only the C terminus but retaining the other domains, including the HD (FLAG-ΔC-HA). This deletion construct produced a protein which was tagged on both termini and whose size was similar to the CDP150 form observed during differentiation. If this C-terminal deletion mutant mimics CDP150, then protein processing should not occur after treatment of cells with hormones and ECM. SCp2 cells were transiently transfected with the FLAG-ΔC-HA mutant prior to treatment with lactogenic hormones in the presence or absence of ECM to induce differentiation. As expected, Western analysis using extracts from transfected cells revealed that no processed CDP forms were generated upon differentiation (Fig. 5A, lane 2).

FIG. 5.

CDP processing during mammary differentiation requires both the HD and the C-terminal domain. (A) The C-terminal domain is required for CDP processing. SCp2 cells were transiently transfected with a vector expressing FLAG-ΔC-HA, which lacks the entire CDP C-terminal region following the HD. Transfected cells were plated on tissue culture dishes with or without ECM in the presence of hormones. Cell lysates were prepared after 4 days and analyzed by Western blotting with FLAG- or HA-specific antibodies. The same lysates were analyzed with β-casein- or actin-specific antibodies to control for differentiation and protein loading (lower panels). (B) The C-terminal domain of CDP is not required for MMTV NRE binding. Nuclear extracts were prepared from undifferentiated SCp2 cells transfected with a FLAG-ΔC-HA-expression construct and incubated without antibodies (lanes 1 and 2), with CDP- or FLAG-specific antibodies (lanes 3 and 4), or with preimmune serum (lane 5) prior to incubation with a labeled probe containing four copies of a CDP-binding site in the promoter-proximal MMTV NRE (pNRE4). Lane 1 shows a reaction without added nuclear extract. Positions of complexes formed by endogenous CDP and transfected CDP are indicated by arrows. (C) CDP processing is disrupted by HD deletion. SCp2 cells were transiently transfected with constructs expressing different CDP deletion mutants and plated on tissue culture dishes in the absence or presence of hormones and ECM. Cell lysates were prepared 4 days after transfection and analyzed by Western blotting using FLAG- or HA-specific antibody. The positions of CDP-specific bands are indicated by arrows.

We previously showed that lactating mammary extracts containing CDP150 lack DNA-binding activity (53). Therefore, SCp2 cells were transfected with FLAG-ΔC-HA prior to nuclear extract preparation and EMSAs. Interestingly, the ΔC mutant protein retained its DNA-binding ability to the MMTV LTR probe in undifferentiated cells, indicating that this CDP form is different from CDP150 (Fig. 5B, lane 2). Furthermore, DNA-binding activities of both the endogenous CDP and ΔC proteins were detectable and confirmed by ablation with specific antibodies (Fig. 5B, lanes 3 and 4). These results suggest that the C-terminal domain is dispensable for CDP repressor function on the MMTV LTR.

One possible model for CDP150 generation is that full-length protein is cleaved within the HD but requires the C-terminal domain for processing. To test this possibility, two additional mutants, one lacking the HD but retaining the C-terminal domain of CDP (FLAG-ΔHD-HA) and the other lacking CR2, CR3, and HD (FLAG-ΔCR23HD), were tested (Fig. 4A). Transfection experiments followed by Western blot analysis revealed that neither protein was processed (Fig. 5C). In contrast, the mutant lacking the N terminus, the leucine zipper, and CR1 (FLAG-ΔNLZCR1) was processed after differentiation to give a protein of 50 kDa lower in mass, and this protein retained the N-terminal tag (Fig. 5C). These results suggested that CDP150 is generated by truncation within the HD, a domain which is missing in both ΔHD and ΔCR23HD. Moreover, the N-terminal region of CDP is dispensable for processing, whereas the C-terminal domain is not.

CDP150 acts as a dominant-negative regulator of CDP to elevate MMTV expression.

Our previous data indicated that CDP150 was localized to the nucleus of differentiated mammary cells but lacked DNA-binding activity for the MMTV NREs (53). Therefore, we determined the CDP domains required for binding to the MMTV NREs. The homeodomains of many proteins are highly conserved domains that participate in sequence-specific DNA binding (11) through an α-helix near the HD C terminus known as the “recognition helix” (19). Therefore, we constructed an additional mutant with a deletion of the CDP C-terminal domain and 15 amino acids from the HD that removed the “recognition helix” (FLAG-ΔHD15C). Wild-type and mutant expression vectors then were used for transfections of undifferentiated SCp2 cells and nuclear extract preparation.

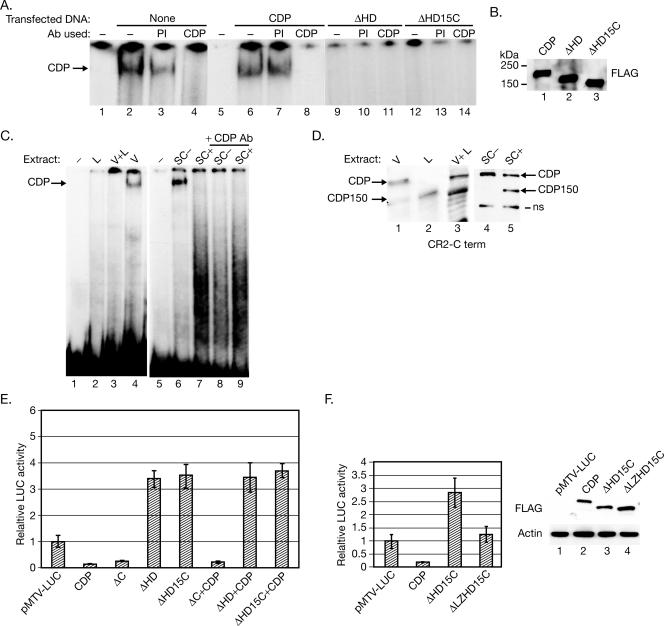

Both CDP and FLAG-ΔC-HA deletion mutants exhibited DNA-binding activity by EMSAs (Fig. 5B). However, the mutants lacking either the HD (ΔHD) or the C-terminal domain together with 15 amino acids from the C-terminal end of HD (ΔHD15C) failed to bind to the MMTV LTR probe (Fig. 6A, lanes 9 and 13). All proteins were expressed in equivalent amounts (Fig. 6B). These results indicate that the HD is required for CDP binding to the viral NREs. Furthermore, transfection of cells with either ΔHD or ΔHD15C, but not ΔC, expression vectors eliminated binding of endogenous CDP to the MMTV LTR (Fig. 5B and 6A), suggesting that CDP isoforms lacking the HD act in a dominant-negative manner to block wild-type CDP binding to DNA.

FIG. 6.

Mixing experiments and transient-transfection assays indicate that CDP150 acts as a dominant-negative CDP mutant. (A) Transfection of CDP mutants lacking the homeodomain into SCp2 cells eliminates endogenous CDP binding to the MMTV NREs. EMSAs with the radiolabeled pNRE probe were performed using nuclear extracts from undifferentiated SCp2 cells (lanes 2 to 4) or cells transfected with wild-type or CDP deletion mutant constructs (lanes 6 to 14). Preimmune serum or antibodies specific for FLAG or CDP were incubated with nuclear extracts prior to addition of probe as indicated. Lanes 1 and 5 show reactions without nuclear extract. The arrow indicates the position of CDP-specific complexes. (B) Western blots reveal equivalent expression of tagged wild-type and CDP deletion mutants in SCp2 cells. (C) Gel shift assays indicate loss of full-length CDP binding to the MMTV NREs in the presence of CDP150. Nuclear extracts (5 μg) from lactating (L) or virgin (V) animals or a 1:1 mixture of these extracts (V+L) were used for EMSAs with the MMTV pNRE probe (lanes 2 to 4). Similar experiments were performed with SCp2 nuclear extracts obtained from cells grown in the absence (SC-) or presence (SC+) of hormones and ECM (lanes 6 to 9). Some extracts were incubated in the presence of CR2-Cterm-specific (CDP) antibody prior to addition of probe (lanes 8 and 9). Lanes 1 and 5 show reactions in the absence of nuclear extract. (D) Western blots reveal intact CDP and CDP150 in nuclear extracts used for EMSAs. Blots containing 30 μg (tissue extracts) or 25 μg (SCp2 extracts) were incubated with the CR2-Cterm-specific antibody; arrows indicate the specific bands. A nonspecific (ns) band is also indicated. (E) Expression of CDP mutants lacking the HD relieves MMTV transcriptional suppression by endogenous or exogenous CDP. Values are reported as described for Fig. 2. The average from transfections of the MMTV LTR-reporter in the absence of a cotransfected CDP-expression construct was assigned a relative value of 1. (F) Deletion of the leucine zipper domain relieves interference with endogenous CDP activity by ΔHD15C. SCp2 cells were transiently transfected with an MMTV-luciferase reporter construct and different full-length or CDP deletion mutants. In the upper panel, data are expressed as described for panel E. Results using pMTV-LUC cotransfected with the wild-type CDP or ΔHD15C were statistically different by the two-tailed Student's t test (P < 0.05) from that obtained using the reporter alone. However, results from pMTV-LUC alone or pMTV-LUC cotransfected with ΔLZHD15C were not statistically different (P > 0.05). In the lower panel, Western blotting demonstrates equivalent expression of all CDP constructs.

To determine if CDP150 observed in differentiated mammary tissue mimics the behavior of ΔHD15C in EMSAs, we performed mixing experiments with nuclear extracts derived from virgin and lactating mammary glands of BALB/c mice. As described previously (53, 54), virgin gland extracts showed considerable binding to the MMTV NREs, which was abolished by CDP-specific antibody, whereas lactating extracts had little or no binding activity (Fig. 6C, lanes 4 and 2, respectively). Mixing of the two extracts to give an approximate 1:1 molar ratio of the two proteins as determined by Western blotting (Fig. 6D, lane 3) eliminated binding to the MMTV NREs (Fig. 6C, lane 3). Similar results were obtained with differentiated SCp2 extracts that contained equal amounts of full-length CDP and CDP150 (Fig. 6C and D). Thus, by size and DNA-binding characteristics, CDP150 and ΔHD15C are indistinguishable.

Dominant-negative proteins should affect the repressor function of CDP on the MMTV NREs. Therefore, MMTV LTR-reporter gene activity was analyzed in cotransfection assays of SCp2 cells (Fig. 6E). As anticipated, the ΔC construct behaved like wild-type CDP in suppressing expression from the viral LTR, indicating that the C-terminal region, which contains the active repression domains (29), is not required for regulating MMTV transcription. In contrast, the CDP deletion mutants lacking the HD (ΔHD and ΔHD15C) failed to repress MMTV LTR activity in transient assays. Interestingly, both of these mutants activated MMTV transcription compared to cells transfected with empty vector.

To further test the idea that CDP150 acts as a dominant-negative protein, the ΔHD15C expression plasmid was modified by deletion of the leucine zipper (ΔLZHD15C). Cotransfection of the pMTV-LUC reporter plasmid with ΔLZHD15C eliminated the ability of ΔHD15C to induce expression from the MMTV LTR (Fig. 6F). These results are consistent with results from DNA-binding assays indicating that CDP isoforms lacking all or part of the HD act as dominant-negative proteins that interfere with CDP repressor function.

CDP150 regulates β-casein and other mammary-specific genes.

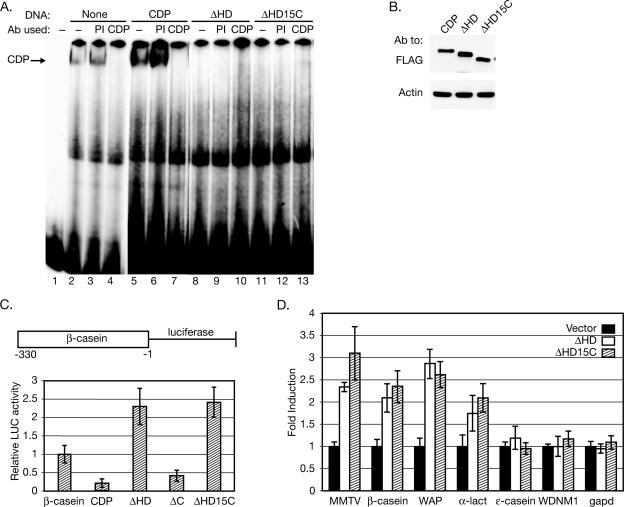

We previously have shown that Cutl1/CDP knockout mice have increased expression of MMTV and several mammary-specific genes (54). To determine whether the dominant-negative activity of CDP150 was restricted to the MMTV LTR, we tested the binding ability of mutant CDP proteins to the β-casein promoter. Similar to results observed with the MMTV NRE probe, EMSAs using extracts derived from transfected SCp2 cells revealed that full-length CDP could bind to the β-casein probe, whereas constructs lacking all or part of the HD could not (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, CDP constructs without the HD interfered with endogenous CDP binding. Western blotting of the nuclear extracts confirmed the expression of the transfected proteins (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

CDP constructs lacking the HD act as dominant-negative mutants on the β-casein promoter and elevate expression of mammary-specific genes. (A) Expression of HD deletion mutants of CDP that mimic CDP150 interfere with full-length CDP binding to the β-casein promoter. Nuclear extracts from untransfected SCp2 cells grown in the absence of differentiation conditions (lanes 2 to 4) or similar cells transfected with constructs expressing full-length CDP, ΔHD, or ΔHD15C (lanes 5 to 13) were used in EMSAs with a radiolabeled probe from the β-casein promoter. The arrow indicates the CDP-specific band. Lane 1 contains a reaction lacking nuclear extract. Some extracts were incubated with preimmune (PI) or CR2-C-term-specific (CDP) antibody prior to probe addition. (B) Western blots indicating equivalent expression of tagged CDP constructs. (C) Transfection of CDP mutants lacking the HD relieves repression of the β-casein promoter in undifferentiated mammary cells. Values were reported as described in the legend for Fig. 2. The average value of reporter gene transfections in the absence of cotransfected CDP constructs was assigned a relative value of 1. (D) Expression of CDP constructs lacking the HD in undifferentiated mammary cells elevates endogenous mammary-specific gene expression. Semiquantitative RT-PCRs were performed in triplicate using primers specific for the indicated genes and normalized for gapd expression. The mean for RT-PCR with each primer set in vector-transfected cells was assigned a relative value of 1 for pair-wise comparisons with transfected cells. The results of RT-PCRs of transfected cells with MMTV, β-casein, WAP, and α-lactalbumin (α-lact) were statistically different from those of empty vector-transfected cells by the two-tailed Student's t test (P < 0.05).

To test the effect of various CDP constructs on the activity of the β-casein promoter upstream of a luciferase reporter, undifferentiated SCp2 mammary cells were used for additional transfections. As anticipated, full-length CDP repressed luciferase levels ca. fivefold, and similar results were obtained after expression of the ΔC protein (Fig. 7C). However, constructs carrying a deletion of all or part of the HD increased luciferase activity from two- to threefold. To confirm and extend these findings, we assayed the endogenous levels of several mammary-specific genes by semiquantitative RT-PCR after expression of either ΔHD or ΔHD15C in SCp2 cells. Similar to expression assays with reporter vectors, CDP constructs lacking a functional HD elevated endogenous MMTV and β-casein expression two- to threefold (Fig. 7D). Increased amounts of whey acidic protein (WAP) and α-lactalbumin mRNAs also were observed in the presence of ΔHD or ΔHD15C proteins. However, in agreement with our studies of Cutl1 knockout mice (54), there was no significant effect on ɛ-casein or WDNM1 in mammary cells. Together, our results suggest that CDP150 is a novel, differentiation-induced, dominant-negative protein that appears during mammary gland development to increase the expression of multiple mammary-specific genes.

DISCUSSION

Negative regulation is known to play a significant role in mediating tissue-specific MMTV expression (41). Our previous experiments showed that CDP acts as a transcriptional repressor of MMTV expression in the mammary gland (53). CDP DNA-binding activity for the MMTV LTR is high in virgin mammary gland, where MMTV transcription is normally repressed (53, 54). During lactation, a period that shows the highest levels of MMTV transcription, CDP-binding activity for the LTR disappears and is accompanied by the appearance of a novel truncated form of CDP, CDP150 (53, 54). This result was confirmed in rat mammary glands (Fig. 1C), suggesting that the mechanism may be conserved in mammals. In the present study, CDP developmental regulation has been recapitulated in SCp2 cells, a normal mammary epithelial cell line, which can be induced to differentiate in culture (10). CDP levels decline in SCp2 cells under conditions that allow synthesis of differentiation-specific proteins, specifically β-casein (Fig. 1). Moreover, DNA-binding activity for the MMTV NREs disappears concomitantly with the appearance of CDP150 during SCp2 differentiation.

The CDP isoforms found in differentiated mammary cells in culture and in vivo appear to be identical. The CDP150 forms found in lactating mammary glands and differentiated SCp2 cells share similar size, reactivity with antibodies, and failure to bind to the MMTV NREs. Further, the appearance of CDP150 correlates in vivo and in culture with increased MMTV expression (53) (Fig. 2). Characterization of CDP150 has been very difficult because no method exists to identify the C terminus of every protein. Even in cases where the method works, much greater protein quantities are required compared to that needed for N-terminal sequencing. Moreover, mass spectrometry analysis does not detect all peptides, and clear identification of a truncated C-terminal peptide is not possible (8; R. Kobayashi, personal communication). However, the ΔHD15C mutant mimics the biochemical, serological, and functional characteristics observed for the CDP150 isoform.

CDP150 appears to act as a dominant-negative protein. Mixing of extracts from differentiated and undifferentiated cells obtained either in vivo or from cell cultures leads to loss of DNA binding to the MMTV NREs (Fig. 6). We have demonstrated that loss of all or part of the CDP HD abrogated binding to the MMTV LTR and the β-casein promoters in spite of retaining three other DNA-binding domains (Fig. 6 and 7). The CDP HD is a highly conserved domain that has been shown to be essential for DNA binding in other homeoproteins (11). An important characteristic of the HD is the presence of the C-terminal helix-turn-helix motif, which mediates DNA binding (19). Since CDP150 lacks binding activity for the MMTV and β-casein promoters, removal of the HD C terminus likely interferes with sequences essential for DNA binding. Moreover, the CDP mutants ΔHD and ΔHD15C failed to bind to the MMTV NREs or the β-casein promoter or to repress reporter gene expression in transient assays (Fig. 6 and 7). These mutant CDPs were able to stimulate expression from reporter gene constructs, suggesting that they act as dominant-negative proteins by dimer formation with full-length CDP. Although CDP150 might act as a positive regulator to activate MMTV expression during differentiation, we have been unable to detect binding of either ΔHD or ΔHD15C to the MMTV LTR (data not shown). Furthermore, removal of the leucine zipper from the ΔHD15C protein eliminates its ability to interfere with the function of full-length CDP, consistent with a dominant-negative activity on the MMTV promoter (Fig. 6F).

Multiple isoforms of Cutl1/CDP have been characterized (18, 25, 32). The p110 isoform is proteolytically processed to remove the N terminus by a nuclear form of cathepsin L at the G1/S transition of the cell cycle (17). This form, which contains CR2, CR3, and HD, has been reported to stably interact with DNA and to be overexpressed in uterine leiomyomas (33). A shorter isoform of 75 kDa contains only two DNA-binding domains, CR3 and HD, and is generated by transcription initiation in intron 20 (18). The p75 protein is expressed in CD4+ CD8+ and CD4+ T cells and in many breast tumor cells, but not normal mammary tissue (18). Another isoform, Cut-alternatively spliced product (CASP), has the N-terminal leucine zipper, but no DNA-binding domains, and has been proposed to act as a dominant-negative protein (25). However, more recent evidence indicates that CASP is a cytoplasmic Golgi protein of 80 kDa with a unique C terminus and similarities to golgin 84 and giantin (16). Thus, all previously described nuclear CDP isoforms lack various portions of the N terminus. The CDP150 isoform is novel because it only appears after mammary differentiation, has a nuclear location, lacks DNA-binding activity for the MMTV and β-casein promoters, has a different mass than other described isoforms, lacks the C terminus, and acts as a dominant-negative protein.

Several models were evaluated to explain the appearance of CDP150 during mammary epithelial cell differentiation. Assays for alternative splicing by RT-PCR indicated that there was no detectable difference between CDP RNA transcripts found in virgin and lactating mammary gland (data not shown). Studies of C/EBPβ in mammary cells have revealed control of translational initiation to give isoforms with dominant-negative activity (3). However, these forms are missing the N-terminal portions of the C/EBP full-length proteins, in contrast to CDP150, which lacks the C terminus (Fig. 1). Further support for C-terminal processing was provided by transfection of tagged forms of full-length and various CDP mutants in SCp2 cells, consistent with C-terminal processing within the HD to generate the truncated form (Fig. 3 and 4). Since all of the tagged proteins were produced by transfections of cDNA expression vectors and because the cysteine protease inhibitor E64d, but not other inhibitors, interfere with production of endogenous CDP150, our data support CDP150 production by proteolytic processing, which appears to be induced specifically in the presence of extracellular matrix (Fig. 1D). Loss of the HD prevented CDP processing during mammary cell differentiation, indicating that the cleavage site is within the HD (Fig. 5). Nevertheless, mutants lacking only the C-terminal domain revealed that this region is essential for correct processing (Fig. 5). CDP also undergoes posttranslational modification at the C terminus (unpublished data). However, the nature of the responsible protease, whether there is protease activation during differentiation, and whether CDP is modified as a prerequisite for cleavage during mammary development have yet to be determined.

Addition of the E64d protease inhibitor blocked the appearance of CDP150 in the presence of differentiation conditions as determined by Western blotting, but not the overall level of β-casein protein (Fig. 3C). In differentiated mammary cells, transcriptional activators may overcome the repressor effects of full-length CDP on MMTV and other mammary-specific genes, including β-casein. Our data suggest that CDP cleavage is essential for developmentally specific induction of β-casein mRNA, which occurs during late pregnancy (39). However, the presence of lactogenic hormones and positive factors are required for maximal β-casein production during lactation. Overexpression of the dominant-negative protein CDP150 in the absence of differentiation conditions (39, 40) (Fig. 7C and D) will lower the amount of functional CDP, leading to an increase in MMTV and β-casein RNA. Thus, our data support a model where CDP cleavage begins during late pregnancy (Fig. 1B), but large-scale production of MMTV and β-casein proteins requires positive regulators that are expressed during lactation in highly differentiated cells.

Proteolytic processing is an important form of regulation in a number of cellular processes. For example, processing of C-terminal IκB sequences from NF-κB p105 contributes to nuclear translocation of the p50 isoform (34). However, CDP processing during mammary differentiation did not relocalize CDP150 to the cytoplasm. In some cases, specific proteolytic cleavage serves to generate novel isoforms with altered biochemical activities. Cleavage of full-length C/EBPβ in the liver also has been proposed to give a dominant-negative isoform that binds to DNA but lacks transactivation potential (50). Previous studies have shown that CDP DNA-binding activity is inhibited by different posttranslational modifications, i.e., phosphorylation and acetylation, during differentiation of several cell types (9, 23). We have demonstrated that CDP DNA-binding activity for the MMTV and β-casein promoters is regulated during mammary differentiation due to proteolytic processing of full-length CDP.

MMTV has long served as a model for mammary-specific gene regulation (7). Our experiments indicate that CDP is differentially expressed in the mammary gland to regulate MMTV and several cellular genes, e.g., β-casein, WAP, and α-lactalbumin, which are expressed at their highest levels during lactation (Fig. 7). The generation of a dominant-negative CDP by intranuclear cleavage represents a novel form of regulation for multiple genes in the developing mammary gland.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Dudley laboratory and Jon Huibregtse for helpful comments on the manuscript. Alain Nepveu generously provided the N-terminal CDP-specific antibody. We also are grateful to Mina Bissell and members of her laboratory for providing SCp2 cells and antibody specific for β-casein.

This work was supported by grants R01CA34780 and DAMD17-01-1-0424 from the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andres, V., B. Nadal-Ginard, and V. Mahdavi. 1992. Clox, a mammalian homeobox gene related to Drosophila cut, encodes DNA-binding regulatory proteins differentially expressed during development. Development 116:321-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aufiero, B., E. J. Neufeld, and S. H. Orkin. 1994. Sequence-specific DNA binding of individual cut repeats of the human CCAAT displacement/cut homeodomain protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:7757-7761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldwin, B. R., N. A. Timchenko, and C. A. Zahnow. 2004. Epidermal growth factor receptor stimulation activates the RNA binding protein CUG-BP1 and increases expression of C/EBPβ-LIP in mammary epithelial cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:3682-3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banan, M., I. C. Rojas, W. H. Lee, H. L. King, J. V. Harriss, R. Kobayashi, C. F. Webb, and P. D. Gottlieb. 1997. Interaction of the nuclear matrix-associated region (MAR)-binding proteins, SATB1 and CDP/Cux, with a MAR element (L2a) in an upstream regulatory region of the mouse CD8α gene. J. Biol. Chem. 272:18440-18452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blochlinger, K., R. Bodmer, J. Jack, L. Y. Jan, and Y. N. Jan. 1988. Primary structure and expression of a product from cut, a locus involved in specifying sensory organ identity in Drosophila. Nature 333:629-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blochlinger, K., L. Y. Jan, and Y. N. Jan. 1991. Transformation of sensory organ identity by ectopic expression of Cut in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 5:1124-1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardiff, R. D., and W. J. Muller. 1993. Transgenic mouse models of mammary tumorigenesis. Cancer Surveys 16:97-113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casagranda, F., and J. F. Wilshire. 1994. C-terminal sequencing of peptides. The thiocyanate degradation method. Methods Mol. Biol. 32:335-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coqueret, O., N. Martin, G. Berube, M. Rabbat, D. W. Litchfield, and A. Nepveu. 1998. DNA binding by cut homeodomain proteins is down-modulated by casein kinase II. J. Biol. Chem. 273:2561-2566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desprez, P. Y., E. Hara, M. J. Bissell, and J. Campisi. 1995. Suppression of mammary epithelial cell differentiation by the helix-loop-helix protein Id-1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:3398-3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dragan, A. I., Z. Li, E. N. Makeyeva, E. I. Milgotina, Y. Liu, C. Crane-Robinson, and P. L. Privalov. 2006. Forces driving the binding of homeodomains to DNA. Biochemistry 45:141-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dufort, D., and A. Nepveu. 1994. The human cut homeodomain protein represses transcription from the c-myc promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:4251-4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellis, T., L. Gambardella, M. Horcher, S. Tschanz, J. Capol, P. Bertram, W. Jochum, Y. Barrandon, and M. Busslinger. 2001. The transcriptional repressor CDP (Cutl1) is essential for epithelial cell differentiation of the lung and the hair follicle. Genes Dev. 15:2307-2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erturk, E., P. Ostapchuk, S. I. Wells, J. Yang, K. Gregg, A. Nepveu, J. P. Dudley, and P. Hearing. 2003. Binding of CCAAT displacement protein CDP to adenovirus packaging sequences. J. Virol. 77:6255-6264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giangrande, A., and J. Palka. 1990. Genes involved in the development of the peripheral nervous system of Drosophila. Semin. Cell Biol. 1:197-209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillingham, A. K., A. C. Pfeifer, and S. Munro. 2002. CASP, the alternatively spliced product of the gene encoding the CCAAT-displacement protein transcription factor, is a Golgi membrane protein related to giantin. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:3761-3774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goulet, B., A. Baruch, N. S. Moon, M. Poirier, L. L. Sansregret, A. Erickson, M. Bogyo, and A. Nepveu. 2004. A cathepsin L isoform that is devoid of a signal peptide localizes to the nucleus in S phase and processes the CDP/Cux transcription factor. Mol. Cell 14:207-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goulet, B., P. Watson, M. Poirier, L. Leduy, G. Berube, S. Meterissian, P. Jolicoeur, and A. Nepveu. 2002. Characterization of a tissue-specific CDP/Cux isoform, p75, activated in breast tumor cells. Cancer Res. 62:6625-6633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanes, S. D., and R. Brent. 1989. DNA specificity of the bicoid activator protein is determined by homeodomain recognition helix residue 9. Cell 57:1275-1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaul-Ghanekar, R., A. Jalota, L. Pavithra, P. Tucker, and S. Chattopadhyay. 2004. SMAR1 and Cux/CDP modulate chromatin and act as negative regulators of the TCRβ enhancer (Eβ). Nucleic Acids Res. 32:4862-4875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khanna-Gupta, A., T. Zibello, H. Sun, J. Lekstrom-Himes, and N. Berliner. 2001. C/EBPɛ mediates myeloid differentiation and is regulated by the CCAAT displacement protein (CDP/cut). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8000-8005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ledford, A. W., J. G. Brantley, G. Kemeny, T. L. Foreman, S. E. Quaggin, P. Igarashi, S. M. Oberhaus, M. Rodova, J. P. Calvet, and G. B. Vanden Heuvel. 2002. Deregulated expression of the homeobox gene Cux-1 in transgenic mice results in downregulation of p27kip1 expression during nephrogenesis, glomerular abnormalities, and multiorgan hyperplasia. Dev. Biol. 245:157-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, S., B. Aufiero, R. L. Schiltz, and M. J. Walsh. 2000. Regulation of the homeodomain CCAAT displacement/cut protein function by histone acetyltransferases p300/CREB-binding protein (CBP)-associated factor and CBP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:7166-7171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lievens, P. M., J. J. Donady, C. Tufarelli, and E. J. Neufeld. 1995. Repressor activity of CCAAT displacement protein in HL-60 myeloid leukemia cells. J. Biol. Chem. 270:12745-12750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lievens, P. M., C. Tufarelli, J. J. Donady, A. Stagg, and E. J. Neufeld. 1997. CASP, a novel, highly conserved alternative-splicing product of the CDP/cut/cux gene, lacks cut-repeat and homeo DNA-binding domains, and interacts with full-length CDP in vitro. Gene 197:73-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu, J., A. Barnett, E. J. Neufeld, and J. P. Dudley. 1999. Homeoproteins CDP and SATB1 interact: potential for tissue-specific regulation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:4918-4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu, J., D. Bramblett, Q. Zhu, M. Lozano, R. Kobayashi, S. R. Ross, and J. P. Dudley. 1997. The matrix attachment region-binding protein SATB1 participates in negative regulation of tissue-specific gene expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:5275-5287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luong, M. X., C. M. van der Meijden, D. Xing, R. Hesselton, E. S. Monuki, S. N. Jones, J. B. Lian, J. L. Stein, G. S. Stein, E. J. Neufeld, and A. J. van Wijnen. 2002. Genetic ablation of the CDP/Cux protein C terminus results in hair cycle defects and reduced male fertility. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:1424-1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mailly, F., G. Berube, R. Harada, P. L. Mao, S. Phillips, and A. Nepveu. 1996. The human cut homeodomain protein can repress gene expression by two distinct mechanisms: active repression and competition for binding site occupancy. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:5346-5357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michallet, M. C., F. Saltel, X. Preville, M. Flacher, J. P. Revillard, and L. Genestier. 2003. Cathepsin-B-dependent apoptosis triggered by antithymocyte globulins: a novel mechanism of T-cell depletion. Blood 102:3719-3726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michl, P., A. R. Ramjaun, O. E. Pardo, P. H. Warne, M. Wagner, R. Poulsom, C. D'Arrigo, K. Ryder, A. Menke, T. Gress, and J. Downward. 2005. CUTL1 is a target of TGFβ signaling that enhances cancer cell motility and invasiveness. Cancer Cell 7:521-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moon, N. S., P. Premdas, M. Truscott, L. Leduy, G. Berube, and A. Nepveu. 2001. S phase-specific proteolytic cleavage is required to activate stable DNA binding by the CDP/Cut homeodomain protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:6332-6345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moon, N. S., Z. W. Rong, P. Premdas, M. Santaguida, G. Berube, and A. Nepveu. 2002. Expression of N-terminally truncated isoforms of CDP/Cux is increased in human uterine leiomyomas. Int. J. Cancer 100:429-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moynagh, P. N. 2005. The NF-κB pathway. J. Cell Sci. 118:4589-4592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagaich, A. K., D. A. Walker, R. Wolford, and G. L. Hager. 2004. Rapid periodic binding and displacement of the glucocorticoid receptor during chromatin remodeling. Mol. Cell 14:163-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nepveu, A. 2001. Role of the multifunctional CDP/Cut/Cux homeodomain transcription factor in regulating differentiation, cell growth and development. Gene 270:1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pattison, S., D. G. Skalnik, and A. Roman. 1997. CCAAT displacement protein, a regulator of differentiation-specific gene expression, binds a negative regulatory element within the 5′ end of the human papillomavirus type 6 long control region. J. Virol. 71:2013-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quaggin, S. E., G. V. Heuvel, K. Golden, R. Bodmer, and P. Igarashi. 1996. Primary structure, neural-specific expression, and chromosomal localization of Cux-2, a second murine homeobox gene related to Drosophila cut. J. Biol. Chem. 271:22624-22634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robinson, G. W., R. A. McKnight, G. H. Smith, and L. Hennighausen. 1995. Mammary epithelial cells undergo secretory differentiation in cycling virgins but require pregnancy for the establishment of terminal differentiation. Development 121:2079-2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosen, J. M., S. L. Woo, and J. P. Comstock. 1975. Regulation of casein messenger RNA during the development of the rat mammary gland. Biochemistry 14:2895-2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ross, S. R., C. L. Hsu, Y. Choi, E. Mok, and J. P. Dudley. 1990. Negative regulation in correct tissue-specific expression of mouse mammary tumor virus in transgenic mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:5822-5829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scherer, S. W., E. J. Neufeld, P. M. Lievens, S. H. Orkin, J. Kim, and L. C. Tsui. 1993. Regional localization of the CCAAT displacement protein gene (CUTL1) to 7q22 by analysis of somatic cell hybrids. Genomics 15:695-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seo, J., M. M. Lozano, and J. P. Dudley. 2005. Nuclear matrix binding regulates SATB1-mediated transcriptional repression. J. Biol. Chem. 280:24600-24609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sinclair, A. M., J. A. Lee, A. Goldstein, D. Xing, S. Liu, R. Ju, P. W. Tucker, E. J. Neufeld, and R. H. Scheuermann. 2001. Lymphoid apoptosis and myeloid hyperplasia in CCAAT displacement protein mutant mice. Blood 98:3658-3667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tavares, A. T., T. Tsukui, and B. J. Izpisua. 2000. Evidence that members of the Cut/Cux/CDP family may be involved in AER positioning and polarizing activity during chick limb development. Development 127:5133-5144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tufarelli, C., Y. Fujiwara, D. C. Zappulla, and E. J. Neufeld. 1998. Hair defects and pup loss in mice with targeted deletion of the first cut repeat domain of the Cux/CDP homeoprotein gene. Dev. Biol. 200:69-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valarche, I., J. P. Tissier-Seta, M. R. Hirsch, S. Martinez, C. Goridis, and J. F. Brunet. 1993. The mouse homeodomain protein Phox2 regulates Ncam promoter activity in concert with Cux/CDP and is a putative determinant of neurotransmitter phenotype. Development 119:881-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vanden Heuvel, G. B., R. Bodmer, K. R. McConnell, G. T. Nagami, and P. Igarashi. 1996. Expression of a cut-related homeobox gene in developing and polycystic mouse kidney. Kidney Int. 50:453-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang, Z., A. Goldstein, R. T. Zong, D. Lin, E. J. Neufeld, R. H. Scheuermann, and P. W. Tucker. 1999. Cux/CDP homeoprotein is a component of NF-μNR and represses the immunoglobulin heavy chain intronic enhancer by antagonizing the bright transcription activator. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:284-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Welm, A. L., N. A. Timchenko, and G. J. Darlington. 1999. C/EBPα regulates generation of C/EBPβ isoforms through activation of specific proteolytic cleavage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:1695-1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yoon, S. O., and D. M. Chikaraishi. 1994. Isolation of two E-box binding factors that interact with the rat tyrosine hydroxylase enhancer. J. Biol. Chem. 269:18453-18462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu, Q., and J. P. Dudley. 2002. CDP binding to multiple sites in the mouse mammary tumor virus long terminal repeat suppresses basal and glucocorticoid-induced transcription. J. Virol. 76:2168-2179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu, Q., K. Gregg, M. Lozano, J. Liu, and J. P. Dudley. 2000. CDP is a repressor of mouse mammary tumor virus expression in the mammary gland. J. Virol. 74:6348-6357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhu, Q., U. Maitra, D. Johnston, M. Lozano, and J. P. Dudley. 2004. The homeodomain protein CDP regulates mammary-specific gene transcription and tumorigenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:4810-4823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]