INTRODUCTION

Recruitment, retention, and development of faculty members have been important concerns of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) in recent years as the faculty shortage has become increasingly acute. As part of these efforts, the AACP has sponsored a 2-hour program at the Midyear Clinical Meeting of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) every year since 2000 (Table 1). This symposium is designed to provide useful information to professional students, post-PharmD residents, and practicing pharmacists about careers in academia. The program has consisted of 3 speakers followed by a panel discussion with audience questions and answers. The first speaker is generally the current President of AACP, who provides an overview of pharmacy education today and outlines future trends in academic pharmacy. The second speaker is a department chair or other academic administrator in a college or school of pharmacy who provides a perspective on what is required for practitioner/educators to achieve success in academia. The third speaker is a practitioner-educator who describes his/her approach to successfully integrating teaching and practice responsibilities with faculty role expectations. All 3 speakers provide their personal perspectives on the benefits and challenges of life in academia. This paper is a compilation of 3 presentations given at a symposium presented at the American Society of Health System Pharmacists (ASHP) Midyear Clinical Meeting in December 2004 entitled, “The Top Ten Reasons to Consider a Career in Academia.” A panel discussion involving all 3 presenters is provided in Appendix 1.

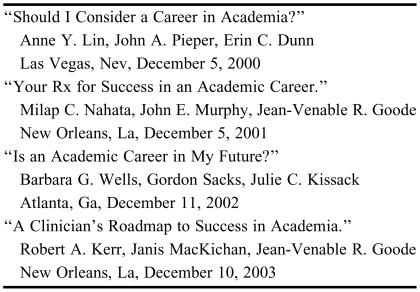

Table 1.

Examples of Previous AACP Symposia on Careers in Academia Held at ASHP Midyear Clinical Meetings

AACP = American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy

ASHP = American Society of Health-System Pharmacists

CURRENT STATE OF ACADEMIC PHARMACY

Adapted from a presentation by JoLaine R. Draugalis

Information Sources on Academic Pharmacy

The American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) compiles various annual reports and profiles that can be used to characterize the academic pharmacy enterprise. These materials can be helpful to individuals investigating the pursuit of an academic career or by current faculty members interested in looking at overall statistics or comparisons among schools. Some of these reports can be found on the AACP web page (www.aacp.org) in addition to being provided to institutions and individual members in hard copy. These include “Academic Pharmacy's Vital Statistics”; “Profile of Pharmacy Students: Application Pool, Enrollments, Degrees Conferred”; and “Profile of Pharmacy Faculty.” The faculty report includes information on appointment types, salary, and faculty demographics. Further differentiation is provided by discipline, public vs. private schools, and other factors. Subsets of these reports are published periodically in the American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education (AJPE), available online at www.ajpe.org.

Characteristics of Pharmacy School Applicants

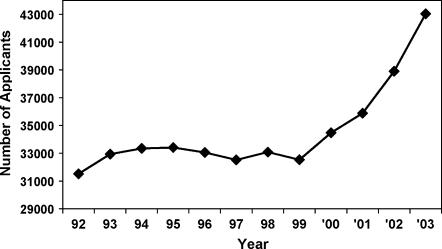

The academic enterprise in pharmacy is currently enjoying very rich applicant pools. A review of statistics across the years reveals that this was not always the case (Figure 1). Even with additional institutions establishing pharmacy programs, there is such high interest in pursuing pharmacy as a career that there are large numbers of highly qualified applicants.

Figure 1.

Number of applicants to US pharmacy schools (1992-2003). Source: American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy.

When considering enrollments by gender, female student enrollment figures have been holding steady at about 62% to 65% of doctor of pharmacy classes since 1990. Women have comprised the majority of pharmacy school enrollments since 1982. The AACP tracks application, enrollment, and graduation statistics for underrepresented minorities as well.

Characteristics of Pharmacy Faculty Members

Type of Appointment

Calendar-year appointments are the norm across the United States for pharmacy faculty. This differs from many other disciplines, particularly those located on a main college or university campus. Most of those faculty members are on 9- or 10-month appointments. In some academic health centers, clinical nursing faculty primarily involved in didactic instruction are also on 9- or 10-month appointments.

Tenure Status

The percentage of faculty members in the tenure stream and the percentage that are tenured have changed dramatically since the 1991-1992 academic year. In the 2004-2005 academic year, 38% of the faculty members were tenured and another 20% were tenure eligible, whereas in 1991-1992 approximately half the faculty were tenured and another 28% were in a tenure-eligible appointment.1,2 In the 1991-1992 academic year, 22% of faculty members were in non-tenure track positions, compared to 42% of faculty members in such positions in 2004-2005. Although there may be many factors at play in this change, one major reason may be the large increase in clinical faculty appointments outside the tenure stream, especially at newer schools that are building their clinical faculty. There are new curriculum content areas such as pharmacogenomics and informatics and delivery mode considerations; for example increased use of small group discussion sections, technology applications, and distance education.

Gender and Racial Diversity

In the benchmark year of 1991-1992, only 25% of all faculty members of all ranks were women and there were no female pharmacy deans.1 Twelve percent of assistant and associate deans, 5% of full professors, and 36% of part-time faculty members were women. In the 2004-2005 academic year, women constituted 40% of all ranks and 19% of the CEO deans. The percentage of female assistant and associate deans has nearly doubled to about 24%, and the percentage of female full professors has increased to almost 17%.

Twelve years ago, 3% of all full-time faculty members were African American, and of those, 41% were women. Currently, only 5% of all full-time faculty members are African American, and of those, 56% are women. The majority of African Americans are affiliated with historically black colleges and universities.

Distribution by Discipline

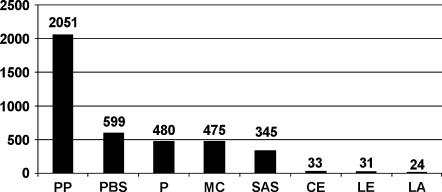

Examination of the distribution of 2004-2005 full-time pharmacy faculty by discipline shows that the number of pharmacy practice faculty members is larger than the number of all other disciplines combined (Figure 2). The conversion to the doctor of pharmacy as the sole entry-level degree, with the concurrent need for increased numbers of advanced practice experiences, is one major reason for this distribution.

Figure 2.

Number of full-time pharmacy faculty by discipline in 2004-2005. Source: American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Legend: PP = Pharmacy Practice; PBS = Pharmacology/Biological Sciences; P = Pharmaceutics; MC = Medicinal Chemistry; SAS = Social/Administrative Sciences; CE = Continuing Education; LE = Libraries/Educational Resources; LA = Liberal Arts.

There is a large group of faculty members that may be described as practitioner-educators, with a variety of appointment types and contracts. A typical pharmacy program has an average of 250 adjunct practitioner-educators.3 Clearly, the experiential portion of the curriculum cannot be delivered without these preceptors. Practitioners who are interested in obtaining an affiliation with a school or college of pharmacy without a full-time academic appointment may wish to consider this option.

The Age Factor

Data for full-time faculty on calendar-year appointments in 2004-2005 show that large numbers of faculty are nearing retirement age, particularly in certain disciplines. This is an important concern, and possible means for addressing it is an ongoing initiative of AACP. Recruitment strategies include having pharmacy students and talented scientists in other disciplines consider preparing for a career in pharmacy academia.

A Career in Academic Pharmacy: Finding Your “Best Fit”

If one decides to pursue an academic career, it will be necessary to determine what programs provide the best fit for the individual as well as what the individual has to offer the program. Considerations include, but are certainly not limited to, class size, other programs housed within the institution, number and type of faculty members, income/revenue sources and amounts for the institution, extent of external research funding, and affiliation agreements with other institutions, especially practice sites.

Ramifications of the Change in the Professional Degree

Part of what is driving the increased need for faculty members has been the tremendous change in the 1990s in the content, process, and outcomes of the curriculum that pharmacy programs deliver. The transition to the doctor of pharmacy as the sole professional degree from a 2-degree system was symbolic of the change, but the transition was much more than simply cosmetic. The curriculum delivery model as well as the extent and depth of content are reasons why so many more pharmacy practice faculty members are required.

From 1992 to 2004, the number of pharmacy schools increased from 75 to 89, and all students are now enrolled in doctor of pharmacy programs. In 1992, only 18% of degrees awarded were the doctor of pharmacy degree.4 There are also 9 affiliate institutional members of AACP at this time. These are schools that have not yet been granted any status from the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and some of these schools may not ultimately offer a pharmacy curriculum. However, after many years of no additional schools and colleges of pharmacy, several academic institutions each year are announcing their intent to start new schools of pharmacy.

The changes in degree status and accompanying curriculum were intended to produce graduates capable of delivering pharmaceutical care, overseeing the medication therapies of patients, and also producing practitioners who are able to pursue a variety of practice options.

Educational Resources

The acronym “CAPE” stands for the Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education. A major initiative of CAPE is to create and publish educational outcomes for the doctor of pharmacy program. The first document was published in 1994, with subsequent revisions in 1998 and 2004. Most schools have used these outcomes as a framework for curricular change as well as for assessing and evaluating their programs. This document is available on the AACP web page. There are 3 overriding themes in the most current rendition: (1) pharmaceutical care, (2) systems management, and (3) public health.

There is also a series of commissioned Excellence Papers that may be useful to those contemplating an academic career. The topics included in this series are: (1) curriculum development and assessment, (2) the culture of scholarship, (3) distance education, and (4) student professionalism. These papers are available on the Journal’s website, www.ajpe.org.

Education Scholar is another project that AACP and several other healthcare professions educational societies have created (www.educationscholar.org). This Web-based program is available for purchase and is targeted not only to pharmacy educators, but to many other healthcare disciplines as well. The program contains a series of 6 modules. Those in the beginning stages of their academic careers might consider purchasing it for themselves. Another creative option is to include the program in the start-up package that is negotiated before appointments are made. This is an intensive program that one can work through individually. Alternatively, some pharmacy schools have faculty teams that work through the modules together.

Why Would You Want To Join Academic Pharmacy?

This section of the presentation is based on the book, The Pleasures of Academe – A Celebration & Defense of Higher Education, by James Axtell.5 The book provides both academic and “pleasure” reasons for considering a career in academia. Each chapter starts with a relevant quotation. In the preface Dr. Axtell stated, “I couldn't wait to go to college and I couldn't stand to leave at graduation, so I became a Professor.”

National norms that are reported by the Higher Education Research Institute (HERI) at UCLA, based on data collected from faculty members across all disciplines on all types of campuses, found that 80% of professors at different types of institutions indicated they would definitely or most probably choose academia again if they had the option to do it over.6 So it seems that we are a fairly happy and satisfied bunch in that regard.

In Axtell's book, 5 academic categories are highlighted, followed by 5 pleasure categories. Chapter 1 is titled “(Mis)Understanding Academic Work.” Carlos Baker is quoted here: “The layman doesn't know what professoring really is.” Many students don't really know what professoring is either, as they assume that the main topic or content area of a faculty member's teaching assignment is all that he or she stands for. This is obviously not a valid assumption for those of us assigned to teach statistics or research design! Students are often not aware of a faculty member's research program or scientific publications. It is also difficult for many students to understand what is involved in phenomena such as contact hours, office hours, one-on-one teaching, mentoring, test preparation, development of a new series of notes and topics for a course, working toward promotion, writing publications, grant submissions, and the existence of different stages of a faculty member's career.

Chapter 2 is titled “Scholarship Reconsidered.” In many aspects of life, the anticipation and preparation for an event may outstrip the actual participation in it (think of your own high school prom or a wedding, for example). We often get so energized to plan something that once it has been achieved or completed, we realize that it was actually more fun getting there. Faculty members have the choice of subjects to pursue in scholarly endeavors, and these often emanate from one's practice site.

In Chapter 3, Axtell lists 25 reasons to publish. The first 8 reasons were professional in nature and referred to the duties of the professoriate. Two additional professional reasons spoke to the tangible rewards of scholarship, and then 15 personal reasons are given. Particularly relevant to the discussion at hand was reason 17, where Axtell stated that a good scholar has 5 crucial attributes of a good teacher: enthusiasm, authority, rigor, honesty, and humility.

In Chapter 4 Axtell talks about encountering the other, which addressed embracing diversity, and this certainly applies to pharmacy and particularly so in pharmacy practice when considering cultural competence in delivering care to patients.

In the fifth chapter, Dr. Axtell suggests criteria to assess true academic excellence rather than relying on mass media ranking systems. Many of the categories suggested are quite similar to professional program accreditation standards, but I would ask you to think about the following Einstein quotation: “Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts, can be counted.” So sometimes it is hard to quantify.

Turning to the 5 pleasures, Chapter 6 is titled, “Confessions of a Bibliolater.” A bibliolater is one who has extravagant devotion to or concern with books. If you remember your favorite books from childhood and you become a collector of volumes, you may end up with an office of volumes literally falling off your shelves. I think this will still be the case even with the advent of electronic publishing. Interprofessional work is necessary for success in providing patient care and conducting scholarly inquiries; thus, Chapter 8, “Between Disciplines,” is quite relevant. Collaboration between clinical faculty members and their social and administrative colleagues just makes good sense.

Dr. Axtell suggests in Chapter 9, “Extracurriculum,” that classroom teaching (and I would also include the experiential component of our teaching) is but a part of teaching that many professors do. Over a lifetime they might reach more “students” outside the classroom (or rotation setting) than within it. This is something that should be considered seriously and is the main joy of academia for many of us. Consider the advising, mentoring, and networking at national meetings. Monday night is always my favorite night at the ASHP Clinical Midyear Meeting, because that's when the Arizona reception is. I enjoy seeing alumni, hearing what everyone is doing, and getting to see students in a different light.

There are social, economic, and cultural advantages to being located in a college or university town, as described in Chapter 10, “College Towns.” We just need to take advantage of the opportunities that are available. Announcements come across the desk or via e-mail for grand rounds, lectures, and presentations, but if we do not take the time to “smell the roses” then we have lost an opportunity that should be one of the more pleasurable aspects of our job. Even though it may seem difficult to find the time to cross the campus to see a dance recital or play, these activities can be very invigorating and refreshing if we just realize the importance of taking advantage of them.

The final chapter, “Academic Vacations,” opens with a quotation from Henrik Ibsen: “Academics are not the most entertaining traveling companions, not in the long run anyway.” I happen to disagree with this notion; many academics have professorially driven vacations and opportunities for travel and make excellent travel companions.

I have certainly found the pleasures to far exceed the troubles in my academic career. I wish you the best in your career decisions and hope that you consider some aspect of academia in your future professional practice.

TEN THINGS THAT EVERY FACULTY MEMBER SHOULD KNOW

Adapted from a presentation by Joseph T. DiPiro

A lot of time and effort is spent recruiting faculty members, retaining, mentoring, and advising them, and trying to help them be successful within a university setting. Although academia provides a tremendous environment for a career with opportunities for growth and development. These opportunities are sometimes difficult for junior faculty to recognize. The following are 10 things that every faculty member should know to succeed in an academic environment.

1. Understand the Value System in Your Organization

It is important to recognize the value system in your institution. This can be viewed from a few different levels. From the university level, colleges of pharmacy differ substantially. Some are large comprehensive research-intensive institutions. There are colleges of pharmacy located within health science centers that do not offer liberal arts and sciences and many other areas that are available at a large comprehensive university. Some colleges are not located in either health science centers or large comprehensive universities, and they have a different character. These differences say a lot about the value system of these institutions that may relate to research, NIH funding, publications, or clinical service and patient care. Admittedly, most institutions have a mix of all these activities, but they differ in emphasis and priorities. So a college of pharmacy that is not in a health science center or not a part of a large comprehensive university may focus more time and effort on teaching activities. This is not to say that teaching is considered to be less important at other types of colleges, but the emphasis and proportion of activity is different. For example, a large comprehensive university without a health science center may give little recognition to patient care.

Colleges of pharmacy do have different value systems, but it is at the department level that we can have the most influence on priorities, construct a value system that is consistent with what we are trying to do within the pharmacy profession, and balance teaching, patient care, and scholarship/research. It is important to have a perspective on what the university values and how you fit into that value system. Another area of differentiation relates to tenure-track and non-tenure track faculty members. Some schools place a high value on tenure-track positions. In some institutions, nontenure-track faculty members may be excluded from some grant awards, teaching awards, and some types of fellowships. Nontenure-track faculty members now make up about 40% of all faculty members at colleges of pharmacy, and this percentage is growing. So this will remain an important issue for our schools.

2. Identify the Successful People in Your Organization

It is important to identify who the successful people are in your institution. When a new faculty member joins a department, one of the best things the leadership can do is guide that person to work with people who are successful. Not many of us can be completely successful and fully understand our complex environments on our own. Having a junior faculty member work in a group with successful people leads to a higher likelihood of success. Senior faculty members can be a great help to junior faculty by inviting them to participate in their work or by pointing out other people who can provide help. However, it is also the responsibility of junior faculty members to seek these people out, to ask “Who is achieving the kind of success that I would like to see in my career,” and to take every opportunity to work with these people. These successful individuals are often found within pharmacy practice departments, but they may also be in other departments in the college and sometimes in other colleges within the university. A wide-ranging search may be required, but this is an important thing to do. When you are associated with successful people, you receive a lot of leads on how to get answers and how to be successful in your own career.

3. Find People Who Are Willing to Help You

New faculty members need people who can serve as mentors and advisors. When I started at the University of Georgia, I went to various people for advice. For example, I may have needed help with a statistical problem or an issue related to teaching. Some of the people I sought out had no time for me. Others offered their time at that moment without hesitation. For some of these latter individuals, I could not detect a limit on the time that they had available for me. But there is no guidebook for this, so you have to ask people and find out who has the time and willingness to help you. Some of these relationships will develop into true mentorship. You may find someone who has a true interest in your development and is willing to spend more personal time and effort in helping you become successful. Find the person who is a true and valuable critic of your work, who will not always just pat you on the back, but who will tell you when something you did was not quite right or that you could have done better. It is important to find a direct, honest, and supportive critic who is truly interested in your progress and development.

4. Appreciate the Difference Between Short- and Long-Term Success

It is important that faculty members, particularly at the beginning of their careers, understand the difference between short-term and long-term successes. Some activities in the first few years of an appointment can build a basis for a good career and can make a lot of other achievements much easier. One of these activities is building a good network of people. This can include mentors, critics, and people who can help you in other ways. You will need people with whom you have established relationships and can call on for help. It takes time to develop these relationships. As a new faculty member, you have good reasons to knock on doors, meet people, and shake hands.

Networking is important, not only within the institution but outside of it as well. Pharmacy (and particularly academic pharmacy) is a relatively small world. We can readily identify people with similar teaching, practice, and research interests. We can get together at meetings and begin to build collaborative networks.

You can invest time and effort at the beginning of your career that increases the likelihood of success in other ways. Building the kind of clinical practice that is a good basis for scholarship in the future is important. For example, you will clearly run into trouble if you agree to a practice activity that requires your attention on a 24-hours-a-day, 7-days-a-week basis. You will obviously burn out in a very short time. Instead, it is much more productive to build a clinical model that makes your time more efficient and facilitates collection of clinical data that can lead to scholarly works.

There are other ways to look at the difference between short-term and long-term success. How do you spend your extra hours away from your primary job? Some people think it is important for their own personal progress and aspirations to moonlight. I discourage faculty members from moonlighting in activities that do not directly contribute to their primary career. The time you spend moonlighting may bring you an extra paycheck next week, but it may not be worthwhile in the long run. Using that 8 hours a week that you would otherwise spend moonlighting for scholarly activities, such as writing a paper, will pay much bigger dividends in the long run.

With respect to writing scholarly papers, it is better to spend more time and effort and have a higher quality paper that gets published in a high quality journal than to publish 2 or more “quick and dirty” papers in less respected journals. A greater number of low-quality papers is not nearly worth one good paper in a highly-respected journal.

5. Know What Is Required for Promotion and Tenure

Most faculty members have had discussions with their department chair about policies and procedures for promotion and tenure. When you start a new position you should have in your hand the written policies for promotion and tenure and be familiar with them. Do not wait until you are due for promotion to become familiar with that document. You should know and understand these policies from day one, and even before day one when you are being recruited for a position. This goes beyond simply knowing the written policies and how they are intended to work within your institution. You should ask the right people, “Who has been successful in promotion and tenure at this institution? How did they do it, and what model did they follow? Who has not been successful? Why weren't they successful, and why didn't they get promoted or tenured?” Most schools have examples of faculty members who have and have not been successful at promotion. It is up to you to identify the reasons for success as well as what works and what does not work.

Some unwritten aspects of the promotion and tenure process involve political factors and networking. Talk with senior faculty members and get their advice outside the formal promotion and tenure committee. In some schools, the promotion and tenure committee reviews all junior faculty members each year. Each individual receives written advice and a vote as to whether or not he or she is making progress toward promotion. That is the formal process, but it is also important to engage in the informal process of talking with senior faculty members. Ask the questions, “How am I doing?” What could I be doing to better assure my promotion or tenure in this system?”

6. Be Aware of the Rights and Authorities of Faculty Members

New faculty members often view the academic organization as being similar to a corporate entity, where the CEO or the dean and departments heads send down the orders and the troops then do what they are told. It is important for new faculty members to recognize that this is often not the case in academia. Faculty members have certain rights and authorities that cannot be infringed by the school administration. You should make an effort to learn about these in the faculty policy and procedure documents or faculty handbook. For example, in most institutions it is primarily a right of the faculty to decide who their colleagues will be and who will be invited to join the faculty. In most schools, search committees are faculty driven, with voting on whether a candidate should be invited to join the faculty. Department heads and deans sometimes drive this process, but it should be a faculty process and faculty members should have weight in these decisions.

Determining the content and structure of the curriculum is also the purview of the faculty members rather than the dean or department heads in a well-functioning organization. Also, the faculty members have primary responsibility for setting policies related to promotion and tenure. In many institutions, student admission decisions are also a right and authority of the faculty members.

7. Recognize What Is Written in Stone and What Is Negotiable

As you grow in a faculty career, you will find more aspects of your position that are negotiable. Important issues such as how much time you spend in specific activities can be negotiated. Individual faculty members within your departments or colleges will have quite different responsibilities and time commitments for various activities related to research, service, and scholarship. When you start a new position, you generally agree to spend, for example, 40% of your time in practice, 40% in teaching, and 20% in scholarly activities. These percentages are not necessarily static; your focus areas for time and effort are usually negotiable as your interests and expertise evolve over time.

Any negotiation is better when conducted from a position of strength or success. As you experience success in your faculty position, you will find that you have more tools with which to negotiate the important aspects of your work. Not all faculty members have the same workload. Faculty members who are successful can modify their workloads through negotiation with administration.

Salary is often more negotiable than faculty members realize. To be successful in this, you need to determine the range of salaries that are paid within your university. Learn how some faculty members worked their way to the higher end of the salary range. Faculty salaries fall within a large range at various universities. Salary is clearly more negotiable than we are often led to believe.

8. Explore Opportunities for Salary Enhancement

Practice faculty members have many opportunities to enhance salary by moonlighting. As discussed previously, there are many more valuable opportunities to enhance salary than through typical moonlighting. It is preferable to enhance one's salary thorough university-related activities. Some schools have created extra compensation plans and supplement policies for clinical faculty members. With these “practice plans,” clinical track faculty members can earn extra salary based on income generated through clinical revenue. A consulting policy can also permit some faculty members to generate additional income. Faculty members may be able to supplement salary within the university in other ways, sometimes with added responsibilities but sometimes within the core responsibilities of a position. The administration may view salary enhancement opportunities as necessary to retain highly qualified faculty. With the current competitive market for pharmacist salaries, it is important to identify ways to compensate faculty members adequately and allow them to achieve their goals financially as well as professionally. There may be a number of opportunities for you to enhance your salary, and it is important to find out as much as you can about how to take advantage of them.

9. Learn How to Compete for Resources

Faculty members have an increasing need for resources as their careers grow, but resources within any institution are limited. It is important to understand how to compete for resources within a department, college, or university. In order to build a program, you need to promote it to others who may not understand its value. Part of the politics of university life is letting people know what you are doing. Create a plan that you can use to promote your program to your department head, to your dean, and to upper administration. The plan must clearly justify why more resources are needed for continued success. It is now common for university administration to use business terminology such as “return on investment.” This is important to consider as you think about how you will build your program and advance it within the college or university.

Administrators are looking for good investments. The limited resources available within a college have to be used wisely, so administrators look for individuals and programs that have a high likelihood of success and are likely to provide a good return on this investment. The more effectively that you promote your program, the more likely you will be to garner resources.

10. Don't Forget the Basics

Always remember to take care of the basics, such as teaching responsibilities and college service. With all of the drive to succeed, forgetting the important basic aspects of your job can lead very quickly to problems. Not attending to basic responsibilities, such as not showing up for class, not going to meetings, or violating policies and procedures can impede progress in other areas. In fact, violation of school or university policies (such as an inaccurate expense report for travel) may lead to termination. All of this has to do with being a good citizen. Small violations of policies can sometimes create big problems; it is important for new faculty members to be aware of policies, follow them meticulously, and ask questions when the policies are not clear.

In summary, much of your future success as an academician relates to your ability to identify and bond with successful people, create mentoring relationships, and build networks with faculty members who have similar interests. There are many policies and procedures that set ground rules and responsibilities, but faculty members also have substantial autonomy and authority. Understanding these aspects of academic life is critical to your future success.

TOP TEN STRATEGIES FOR SUCCESS AS A CLINICIAN EDUCATOR

Adapted from a presentation by Mario M. Zeolla, PharmD

The term clinician educator first appeared in the medical literature in the 1970s and was adopted by medical colleges during the early 1980s after difficulties in faculty retention became more prevalent.7 At the time, the majority of medical college faculty members were employed in traditional tenure-track positions that placed a strong emphasis on scholarly activities. Faculty members also had significant teaching and practice responsibilities, making it difficult to balance these activities with the requirements for successfully funded research programs. As a result, faculty members had difficulty achieving tenure, which caused many individuals to leave academia. The resulting increase in the demand for faculty members led colleges to create new non-tenure track positions that became known as “clinician educator” faculty tracks. These positions, primarily nontenure in nature, allowed faculty members the opportunity to focus on the provision of clinical services while continuing to participate in teaching and scholarly activities.7,8

Pharmacy schools and colleges have subsequently followed this model, and today approximately 95% of schools in the United States employ nontenure-track pharmacy faculty members.9 The titles given to these types of positions vary among institutions, but clinician educator positions in pharmacy have responsibilities similar to those of their medical college counterparts. Faculty time is focused on providing clinical pharmacy services and experiential education. Nontenure track clinical faculty members also participate in didactic teaching, service to the institution, and scholarly activities, but in most cases to a lesser extent than tenure-track faculty members.10 The variety of activities and experiences offered by these positions make them an attractive career option for residency-trained pharmacists who desire the opportunity to provide direct patient care and serve as an educator. However, balancing these unique roles and responsibilities can be a challenge. Success in these positions can be defined in many ways. Regardless of the definition, success can only be achieved with proper planning and a thorough understanding of expectations.

Defining “Success”

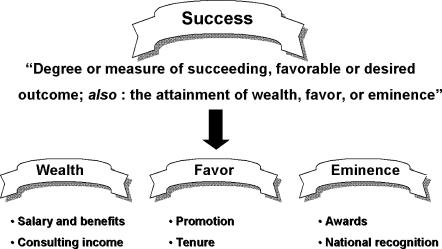

Before discussing strategies for success, it is important to first define what success means and how it is measured in terms of a career as a clinician educator. The Merriam Webster dictionary defines success as “a degree or measure of succeeding, a favorable or desired outcome, and the attainment of wealth, favor or eminence.”11 The latter definition (attainment of wealth, favor or eminence) arguably can be measured objectively in reference to careers in academia (Figure 3). Although a career in academia may not lead to immense monetary wealth, faculty members receive a salary and benefits package that is competitive with other careers in pharmacy. They also have the opportunity to supplement income via external consulting activities (to be discussed below).

Figure 3.

Defining “Success” as a Clinician Educator.

Success can also be measured by the attainment of career advancement milestones, including promotion and/or tenure. Finally, eminence in the form of awards for excellence in education or practice, along with national recognition for expertise in a given field, can also be used to distinguish the successful faculty member.

The aforementioned definition of success does, however, lack perhaps the most important measure of any successful career, and that is personal satisfaction. This aspect of success must be a personal and individual definition and can take on many meanings, the simplest being a sense of accomplishment and a feeling of joy. The remainder of this paper outlines 10 strategies for success as a clinician educator.

Strategy 1: Mentorship Is Key

Mentorship should play a predominant role in all aspects of the career of a clinician educator, and as such it is listed as the first strategy. Mentorship is especially important for a clinical faculty member who needs to juggle a variety of diverse responsibilities and make important decisions along the way. Active mentorship early in a new faculty member's career can assist in guiding the development of career goals and aspirations. However, the mentee must be willing to be accept mentorship and vice versa in order for the relationship to be a success.12

Schools and colleges have also recognized the importance of formal mentorship programs designed to facilitate new faculty members in the mentoring process. I have had the opportunity to participate in the “buddy system” program that the Albany College of Pharmacy has developed. The process involves pairing a new faculty member with a “buddy,” typically a faculty member with a similar area of practice. This person serves as a resource and assists in helping maneuver through the day–to-day activities during the first year at the college. At the start of the second year, new faculty members are asked to choose a formal mentor of record, which does not necessarily need to be the person who was their “buddy.” Some may argue that the mentor-mentee relationship cannot be forced or mandated via a formal process and should be developed over time by individuals with mutual interests and intent. While this is true, most would agree that any process that introduces the concept of mentorship early in a career is beneficial. Choosing a mentor with a similar background and interests can be helpful, as the individual can relate to your situation and understand some of the things that you are dealing with. Few faculty members would say they have had a single mentor guide their progress. I have been fortunate to have multiple mentors beginning as a student and continuing through my residency and current position at the college. Their guidance has been and continues to be invaluable.

Strategy 2: Know Where You Are and Where You Want To Go

Clinician educator positions involve interaction with a variety of individuals and institutions, be it colleagues at the college or pharmacists and patients at practice sites. Knowing the 3 P's is an important step towards success; the policies, the procedures, and the personnel. It is equally important for clinician educators to decide early on where they would like to go in their careers.

Being intimately familiar with the policies and procedures of both the academic institution and practice site will prevent problems and ensure success in day-to-day functions and activities. Long-term success in the form of promotion and/or tenure is more likely to occur when faculty members know early on what it takes to get there (for example, read and understand the promotion and tenure guidelines!). Of the 3 P's, personnel may be the most important, particularly as it relates to practice site activities. Collegiality is an expectation of all professionals within an academic institution. However, it is important for a number of reasons to go beyond this and learn about the interests, activities, and goals of one's colleagues. Within the practice setting, it is particularly important for clinicians to know the individuals they work with on a daily basis. More importantly, efforts must be made to allow people to know the pharmacy clinicians and understand the challenges they face as “part-time” academicians and clinicians.

Setting goals early and reexamining them often is necessary for success by any definition. At the Albany College of Pharmacy, the annual evaluation process includes verbalizing short- and long-term goals and assessing progress toward the previous year's goals. This process is very useful because it forces faculty members to self-assess and reevaluate their activities and interests. It also assists in tracking progress towards the common goal of promotion and/or tenure.

Promotion and tenure criteria vary among institutions and often allow a degree of flexibility, enabling individuals to focus their strengths and professional aspirations. The 3 general areas of teaching, service, and scholarship provide the framework for the activities and responsibilities of clinician educators. Clinical faculty positions involve responsibilities primarily in the areas of teaching (didactic and experiential) and service (to the College, clinical site, and the profession). Experiential education in the form of precepting advanced practice experience students makes up a significant portion of my own teaching activities. However, I have also had the opportunity to teach didactically in large lecture and small group settings. Diversity in teaching activities can increase satisfaction and is encouraged from the standpoint of promotion.

Service to the college comes in the form of committee work, student advising, and other general service function roles. Clinical practitioners are also evaluated on the service provided to the practice site, including patient care activities. Service to the profession, also considered to be important, will be discussed below.

Scholarly contributions are also recognized by most institutional promotion guidelines, but in some cases are not required for clinical track faculty members. Tenure-track faculty members typically have greater expectations in this area than nontenure clinical faculty members. Scholarship definitions vary but include dissemination (in the form of presentations and publications) of innovative teaching activities, practice models, or original research. Other forms of scholarship include publication of review articles, textbook chapters, and service as a journal referee. Typically, excellence must be demonstrated in teaching and/or service to achieve promotion. It is critically important to learn the process and expectations early and plan one's path carefully.

Strategy 3: Establish a Quality Practice Site, But Be Realistic

Faculty members developing practice sites need to accomplish 2 goals. The first is to provide a valuable clinical service and the second is to create a valuable educational experience for students. With careful planning and a bit of trial and error, these 2 goals can be accomplished and often are interrelated. An exemplary practice site consists of several key elements, including having an adequate learning environment, having an excellent learning experience, and having a preceptor on site who will provide these experiences.12 An adequate learning environment requires the necessary resources to achieve both goals. This may include everything from educational resources and “hardware” (eg, laptop computer, reference books) to supportive site personnel. Students must have structured learning experiences that allow them to learn by doing, keeping in mind that they require feedback and guidance each step of the way.

Practice site services and associated learning activities must be realistic in that they must take into account the need for flexibility and time for “on-the-job” training. Clinical faculty members can easily become overburdened by the need to simultaneously serve as practitioners and educators at the site. Ensuring long-term success requires that practice site activities are both valuable to patients and site personnel and allow enough flexibility to balance the needs and responsibilities as an educator.

One of the ways for clinician educators to avoid the need for clones is to keep all parties informed of their roles and responsibilities. This is especially important in shared or “50/50” faculty positions, which have become increasingly popular in recent years. These positions are attractive because they allow individuals interested in academia the opportunity to take on expanded roles as clinical practitioners. A key element for the success of these positions is a clear understanding and communication of responsibilities by both parties early on. Faculty members run the risk of burnout if expectations are not clearly delineated. Additionally, faculty members in shared positions must keep colleagues at the practice site and the college aware of responsibilities for the “other-half.” At the Albany College of Pharmacy, department meetings include an agenda item called Faculty Forum. Each month a faculty member informally presents for 5 to 10 minutes about his/her current activities. This includes a description of current teaching, service, and scholarly activities, as well as activities at the practice site. The opportunity to discuss current activities with the department is especially beneficial for new clinical faculty members who may spend a great deal of time at their site and may be less familiar to other department members. It is equally important for practice site personnel to understand responsibilities to the college. Establishing a quality practice takes continuous assessment and modification to achieve that necessary balance.

Strategy 4: Become the Local Expert in an Area of Interest

Many clinical faculty members enter academia directly after completing a residency training program, many of which are general and do not focus in a particular therapeutic area or patient population. In my case, this consisted of a community pharmacy practice residency with an ambulatory clinic component. Training as a generalist has the benefit of being considered “a jack of all trades.” However, being “a master of none” can have its down side. Since joining the College in 2000, I have found that there can be benefits to pursuing an area of interest and becoming the local “expert” in an area of interest. My own interests developed over time through experiences during my residency and at the College. I began to seek opportunities to get involved in teaching and scholarly activities related to these areas. Initially my teaching assignments consisted of a variety of pharmacotherapy topics, but not necessarily those that interested me most. With time, the opportunity to teach topics of interest became available. Most would agree that it is much more fun to teach a topic that you are passionate about. I have also sought opportunities to engage in scholarly activities related to these areas. For example, serving as a reviewer for various pharmacy journals has allowed me to select topic areas of interest. In addition, I have tried to be selective when it comes to the topics of continuing education presentations I have given. I may never become the national expert in a given field or area, but it has been rewarding both personally and professionally to have a recognized area of interest.

Strategy 5: Never Stop Learning

Many, if not most, clinician educator positions employ an individual with a PharmD degree and at least 1 year of residency training. Clinician-educators must continue to learn and stay abreast of the latest clinical information. Residency programs succeed in training clinical faculty members in their roles as practitioners and efficient self-learners. However, the breadth and extent of training as an educator varies. Most programs provide the opportunity to participate in didactic and experiential teaching activities. Despite this, I felt that I had much to learn about teaching when I was hired as an academician.

Thankfully, I quickly learned that there are numerous professional development opportunities in this area both locally and nationally. The AACP offers a wealth of resources in this area. The Interim and Annual Meetings offer excellent programming to assist in professional develop as an educator. The AACP website also contains a number of valuable resources developed by the organization and its members, as well as links to external education resources. Beyond this, there are specialty conferences and programs available that focus on professional development in the areas of teaching and adult education. Many institutions have instituted faculty development programs and encourage continued educational training. Clinical faculty members can benefit greatly from taking advantage of these opportunities.

As stated above, clinician educators must also stay current with the latest medical and therapeutic information. This can be a challenge given the volume of new information becoming available. Continuing education requirements assist in meeting this need, but often not to the degree that is necessary for a clinical academician. Staying on top of primary literature requires a systematic approach. A number of newsletters and indexing services are available in print and online to aid in this task. They provide current and concise information in a format that is easily accessible. For example, the newsletter Journal Watch summarizes publications from a number of major medical journals and provides commentary on implications of each study. One can also subscribe to Internet services and receive e-mail updates from websites such as Medscape.com. Examples of other useful publications and online services include Pharmacists Letter, APhA Drug Info Line, and the Pharmacotherapy News Network. Regardless of the source, the key point is that staying current requires a proactive approach.

Another aspect of continued professional development worth pursuing is that of additional certifications and/or credentials in a specific area. There are many options available (eg, certified disease manager, certified geriatric pharmacist, board-certified pharmacotherapy specialist) and individuals should consider pursuing those that provide them with the most benefit and fit their personal and professional goals. While these additional credentials may not be necessary to be a successful clinician educator, they do provide an opportunity to demonstrate and maintain proficiency in a given area.

Strategy 6: Take Advantage of Extracurricular Opportunities

Most colleges allow faculty members the opportunity to participate in outside consulting opportunities. Some examples include providing continuing education and serving in advisory roles for the pharmaceutical industry. Faculty members should take advantage of these opportunities, but they should being selective in doing so. When considering whether to participate in such endeavors, one should seek opportunities that provide not only financial gains but professional development as well. The networking that occurs as an academician often leads to these opportunities. Before accepting a consulting assignment, it is important to first be familiar with the academic institution's consulting policy. These policies often specify a maximum percentage of the employee's time that can be devoted to consulting activities and may define specific activities that apply. Whenever possible, pursue activities that offer both professional and personal gains. Opportunities that offer benefits beyond financial gain can often assist towards improving as an educator, clinician, and/or scholar. Finally, avoid saying “yes” to every offer early on. It is critical to understand what a particular task entails and the amount of effort required to complete it before diving in.

Strategy 7: Practice Saying a Two-Letter Word: NO

Jackson et al performed a survey of pharmacy faculty members to assess the level of “burnout” and evaluate characteristics and factors contributing to its occurrence.14 Younger faculty members and those at the assistant professor level had significantly higher levels of burnout based on self-reported survey scores. When specific factors contributing to burnout were evaluated, “lack of time to perform well” scored highest. Early on, new faculty members seek to become involved and tend to say “yes” to every opportunity that comes their way. Doing so can quickly lead to a situation of being in over one's head. All faculty members have diverse responsibilities, which is one of the joys of the position. However, the expectation of multi-tasking can make it difficult to determine when to say “when.” It can take time to learn which opportunities to accept and which to decline. Mentors can play an important role in this regard by providing guidance to new faculty members. Having excellent time management skills from the start can also assist in determining when to say “no” and limit the potential for burnout. For example, purchase of a personal digital assistant (PDA) to replace an inefficient daily planner may be a wise investment. Always take the time to carefully evaluate the risk/benefit ratio before agreeing to take on a new task. Choose those that will aid in achieving your definition of success.

Strategy 8: Serve Your Students and the Profession

Working with students and serving the profession are among the most rewarding activities that academicians enjoy. currently serve as a faculty co-advisor for the American Pharmacists Association Academy of Student Pharmacists chapter at our institution, and it has been one of the most enjoyable things I have done. Regardless of the organization or group, serving in an advisory role and getting involved in student activities can contribute greatly to personal satisfaction, with the added benefit of aiding in professional success.

As scholars and educators, it is also important to serve the profession by active participation in pharmacy organizations. Whether it is on a local, state, or national level, pharmacy organizations provide opportunities to network with colleagues and participate in shaping the future of the profession. They also aid in staying abreast of the issues facing the profession and provide a link between the classroom and practice. Faculty members can also encourage students to become involved in organizations, which may provide valuable learning experiences for them. Finally, it is impossible serve the profession without serving our patients.

Strategy 9: Collaborate

Most experienced faculty members would agree that achieving success requires a collaborate effort. At my institution I have had the benefit of working closely with colleagues in the same practicing setting, and our joint efforts have enabled success in a number of areas. During my third year at the College, another colleague who also practices in a community setting suggested that we develop an informal collaborative group called the Community Pharmacy Practice Group or CPPG. Our institution had 4 faculty members and a resident devoted to this practice setting, so it made sense to work together. Since forming, the group has worked together in all 3 areas of academic life. From a teaching standpoint, we have developed shared clerkship activities to enable us to be more efficient. This has included working together by precepting joint journal clubs or case presentations sessions with our students. We have also worked together on a joint orientation session for our community pharmacy advanced practice students to prevent redundancy. Finally, we have participated in a unique training program for community pharmacists who wish to become advanced practice preceptors. These joint activities have improved the overall quality of our experiential education activities.

In addition to enhancing teaching activities, collaboration can play an important role in the success of scholarly activities as well. Clinical faculty members may have limited training in the area of scholarship. Depending on the expectations in this area, nontenure-track faculty members may find it challenging to achieve these goals. Working with a group of colleagues on joint scholarly activities provides a form of on-the-job training and also allows for greater productivity by distributing the work. This can be especially effective when the group includes tenure-track faculty members with greater expertise in this area. Finally, working with colleagues of a similar practice setting can provide a kind of “support group” that enables faculty members to share challenging experiences and discuss solutions.

Strategy 10: Reap the Rewards of the Position

The number one strategy (if you can call it that) is to “reap the rewards of the position.” This simply involves recognizing the many ways in which this type of position is unique and rewarding. There are few positions in pharmacy that offer such a wide variety of diverse activities and responsibilities in both a clinical and academic setting. Pharmacy practice faculty members, particularly clinical faculty members, have the opportunity to experience the best of both worlds. On any given day there is the opportunity to make a significant impact on the care of a patient, and later that same day make a significant impact on the life of a student or the future of the profession. Clinician educators get to both practice what they teach and have the freedom to explore their own interests and create new knowledge. Time and effort also bring the opportunity for advancement. Faculty positions allow one to enjoy the flexibility that allows a life outside of the office or clinic. It is human nature to experience boredom with repetition. After almost 5 years, I have yet to be bored. This is not to say that there are not days when things do not seem so rosy. However, in the grand scheme of things the rewards clearly outweigh the challenges.

CONCLUSION

Opportunities abound for clinical practitioners who pursue careers in academic pharmacy. A position as clinician-educator offers a unique blend of patient care and academic activities. New faculty members can enhance their likelihood of success by learning about the academic environment, creating mentoring re lationships, and understanding the expectations of academia. Although the challenges are many, the rewards can be great for those who are committed to achieving their personal vision of professional success.

Appendix 1. Panel Discussion

Question: What does the panel think the pharmacy practice department of 2024 will look like, and what do you think the department is going to be engaged in, in terms of the scholarship of pharmacy practice?

Dr. DiPiro: It is difficult to predict 20 years into the future. One might consider current pharmacy manpower projections that indicate where the need for pharmacists will be. That points toward growth in primary care; so I foresee many of our programs emphasizing their community-based and primary care programs. Some things that are in the planning stages now could have a big impact on what we can do in these areas. For example, if medication therapy management under the Medicare Modernization Act provides more revenue to schools, we will be able to expand our practice mission. With regard to scholarship and research, our departments need to continue to be leaders in developing models of pharmacy care, creating new practice models, and promoting those to the profession.

Dr. Draugalis: As a follow-up to that, we also need to be leaders in developing models for the delivery of the educational programs. Some schools offer aspects of their programs through distance learning, such as through teleconferencing and the Internet. This trend will undoubtedly increase, so we must ensure that educational outcomes are not adversely affected.

Dr. Zeolla: The changes that will occur in our profession will dictate what happens in education. There will be many opportunities in the years ahead, but we cannot be certain what the changes will be. The trend that we have already seen with increases in clinical faculty would likely increase if additional opportunities for revenue-generating services become available, particularly in ambulatory and community settings.

Question: How is teaching in medical schools different from that of pharmacy schools?

Dr. DiPiro: Based on my experience, I think the major area of change within medical schools over the past decade or so has been the divergence of research and clinical faculty. In years past, medical school faculty members did research, clinical practice, and teaching. Today many physician faculty members spend most of their time developing their clinical service and then teach within that clinical service. On the other hand, other physicians and faculty members with PhD degrees may be across the street in the research labs spending perhaps 90% of their time doing research and working with graduate students. Although most medical school faculty are involved in teaching, they probably do less clinical and didactic teaching than pharmacy school faculty, especially pharmacy practice faculty.

Question: My question concerns start-up packages. Traditionally, start-up packages have been reserved for tenure-track positions and have often involved rather large sums of money. With the trend to having more clinical-track positions in pharmacy schools, have your institutions implemented start-up packages for non-tenure track clinical faculty, and if so what is the range of these packages? This is important for people seeking faculty appointments to consider up front because a person usually loses negotiating power after a position has been accepted.

Dr. DiPiro: When I recruit someone to join the faculty, I ask them, “What is it that you need?” Laboratory-based faculty may need a lot in terms of dollars and equipment. Pharmacy practice faculty generally don't need as much: usually an office, computer, and some other things. Social and administrative pharmacy faculty may be somewhere in between. To me, that is the key question: “What do you need?” After getting the answer, the department head and dean need to try and meet those needs. We do everything we can to do so. In about the last four years of my previous position at the University of Georgia, we provided start-up packages for all faculty, tenure track and non-tenure track, who are working in pharmacy practice. The packages will differ, but the key thing is to find out what the faculty member needs to be successful in the next few years.

Dr. Zeolla: When I was hired as a new faculty member in a non-tenure track position, the school did have a mechanism in place to provide start-up funds for clinical faculty. So I had the opportunity to negotiate based on what my needs were, including the opportunity to purchase resources such as textbooks and hardware for my practice site.

Dr. Draugalis: The strategy for success will differ among individuals. It is important not to assume anything. Consider negotiating membership dues for a practice organization that will help foster your professional development. Also consider asking for funds to travel to meetings of that organization. I encourage you to attend the AACP annual meeting because of the educational and networking opportunities it will offer you. Also consider seed grants for pilot research studies you would like to start, which may lead to additional funding later.

Question: As a pharmacy practice resident, I have a question about specialty residencies and fellowships. If I go on to do another year in a specialty residency, will that limit my options as a faculty member? On the other hand, if I start a faculty position after completing a general practice residency, does that keep my options open to practice in any area? What advice do you have on whether a person should do a specialty residency or fellowship or just go ahead and test the waters, so to speak? After six years of school and a one-year residency, I have no money.

Dr. DiPiro: I have the opportunity to talk with many of our students and residents about this very issue. The key point is the degree of your interest in research, and whether you see your career developing along research lines, particularly clinical research. If you do, that would favor doing a fellowship. By definition, fellowships should involve about 80% of time in research activities. There is time available for developing additional clinical skills, but that is not the emphasis of those programs. On the other hand, if you see yourself being a high level clinical practitioner and educator, then I think a specialty residency is clearly the direction you should consider. I don't think the choice of a particular specialty is so critical. For example, a specialist in infectious diseases can practice in many different areas such as general medicine, pediatrics, or critical care. A critical care specialist can practice in a lot of different areas as well.

Dr. Zeolla: There are many opportunities available to you, and continuing on for a specialty residency should not be viewed as closing doors. In fact, I think it opens additional doors, and perhaps doors that you may not have had the opportunity to pursue without the specialty residency. Also, some faculty members who were trained in a particular specialty area go on and do something very different later on. This may involve moving from inpatient to outpatient practice or from one specialty to another based on need or changes in long-term goals.

Dr. Schwinghammer: Taking that another step further, what are your recommendations on the minimum entry requirements for a faculty member who is funded by the school? For example, would your school hire someone who has completed a pharmacy practice residency, or do you favor those who have gone on and done a specialty residency or fellowship beyond that?

Dr. DiPiro: We will hire people who have finished a pharmacy practice residency if that experience is a good match for their anticipated role and expectations. We prefer someone with specialty training for most positions in the hospital because most of the specialties are in hospital-related areas, such as critical care, oncology, and pediatrics. For other areas such as the community, we have just begun in the last few years to develop training programs in those areas.

Question: Some schools have relationships with undergraduate colleges. Students who are accepted into these programs complete two years of undergraduate pre-pharmacy study and are then automatically accepted into the school of pharmacy for the four-year doctor of pharmacy program. Who currently teaches those undergraduate classes, and do you see the opportunity for pharmacists to teach at the pre-pharmacy level and interact with upcoming new pharmacists from year one of their postsecondary education?

Dr. DiPiro: We admit to the PharmD program after the pre-pharmacy curriculum. Our students come from a lot of different institutions, and we don't admit right out of high school. From the perspective of the college of pharmacy, it is an advantage in selecting the best students to be able to review their experience during two years of college and then make an admission decision based on applications. I'm sure it is reassuring to pre-pharmacy students to obtain admission into a school of pharmacy early on. But given the highly competitive nature of pharmacy school admissions presently, I think it is to the school's advantage to weigh their pre-pharmacy performance in that admissions decision.

Follow-up Question: Who should be teaching those pre-pharmacy classes? Is this a future opportunity for pharmacists?

Dr. DiPiro: I don't see pharmacy faculty teaching pre-pharmacy and liberal arts courses. But there may be value in having a pharmacy-directed or pharmacy-related course in those first two years.

Follow-up Question: That is what I am referring to. Some of the pre-pharmacy curricula I am familiar with have some rudimentary pharmacokinetics and pharmacology courses. I wonder who is teaching those classes now, and would pharmacy faculty be better qualified?

Dr. DiPiro: That would be difficult for schools of pharmacy who admit pre-pharmacy students from perhaps several dozen different schools from a broad geographic area. Some students would have taken those course but others would not have.

Question: Many current residents and new graduates are interested in careers in academia but are limited by geography due to family issues, or who may lose touch with that interest in academia because there are no positions currently open at the colleges. What do you recommend to those residents or new graduates so that they stay competitive for a career in academia and don't lose touch with that if they are presented limited by geography?

Dr. Draugalis: One thing these individuals can do is keep abreast of advertisements in both ASHP and APhA News as well as the AACP website. They can also review the websites for schools in their geographic area. It may also be helpful to have a personal connection at a nearby school to learn about additional faculty lines becoming available. The web pages of some professional associations also have job boards with postings of positions available.

Dr. Zeolla: Also consider becoming involved in a college as an adjunct faculty member and preceptor. Institutions would welcome you with open arms, especially if you can provide an additional experiential learning site. Getting involved in experiential education is a great opportunity to begin to develop a practice site and a clerkship site that you may be able to continue to use when you have the opportunity to join an institution as a faculty member. It's also important to note that your training stays with you whether or not you go into academia immediately.

Dr. DiPiro: I am frequently made aware of people who are working at a distance. Many colleges of pharmacy have an emphasis on distance education and Internet-based education. There may be some unique opportunities for you right where you are as a distance education instructor for students all around the country.

REFERENCES

- 1.1991-92 Profile of Pharmacy Faculty. Alexandria, Va: American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.2004-05 Profile of Pharmacy Faculty. Alexandria, Va: American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harralson AF. Financial, personnel, and curricular characteristics of advanced practice experience programs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67 Article 17. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer SM. The pharmacy student population: applications received 1991-92, degrees conferred 1991-92, Fall 1992 enrollments. Am J Pharm Educ. 1993;57:89S–99S. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Axtell J. The Pleasures of Academe – A Celebration & Defense of Higher Education. Lincoln NE: University of Nebraska Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindholm JA, Astin AW, Sax LJ, Korn WS. The American College Teacher – National Norms for the 2001-02 HERI Faculty Survey. Los Angeles CA: Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA,; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones RF. Clinician-educator faculty tracks in US medical schools. J Med Educ. 1987;62:444–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198705000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parris M, Stemmler EJ. Development of clinician-educator faculty track at the University of Pennsylvania. J Med Educ. 1984;59:465–70. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198406000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Personal Communication. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, November 2004.

- 10.Glover ML, Deziel-Evans L. Comparison of responsibilities of tenure versus non-tenure track pharmacy practice faculty. Am J Pharm Educ. 2002;66:388–91. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Merriam Webster Online Dictionary. Accessed November 4, 2004. Available at: http://12.129.203.36/cgi-in/dictionary?book=Dictionary&va=success&x=19&y=7.

- 12.Haines ST. The mentor–protége relationship. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67:Article 82. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Littlefield LC, Haines ST, Harralson AF, Schwartz AH, Sheaffer SL, Zeolla MM, Flynn AA. Academic pharmacy's role in advancing practice and assuring quality in experiential education: Report of the 2003-2004 Professional Affairs Committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(Suppl):Article S8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson RA, Barnett CW, Stajich GV, Murphy JE. An analysis of burnout among school of pharmacy faculty. Am J Pharm Educ. 1993;57:9–17. [Google Scholar]