Abstract

Objectives

To develop and implement a competency-based assessment process for the experiential component of a pharmacy education curriculum.

Design

A consultative process was used in the development of new assessment forms and policies, and a survey regarding student and faculty satisfaction was conducted. Information received from the survey and from consultations with faculty preceptors resulted in revision of the forms in subsequent years.

Assessment

Faculty and student perceptions of the assessment process were generally positive. We were moderately successful in reducing grade inflation. The new process also provides the school with data that can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of our curriculum in preparing students for practice.

Conclusions

Development and implementation of a competency-based assessment process require a considerable amount of work from dedicated faculty members. With health professions schools under pressure to provide evidence of their graduates’ clinical competence, this is a worthwhile investment.

Keywords: advanced pharmacy practice experience, assessment, competency-based

INTRODUCTION

Public concern regarding the skills and efficacy of professionals and increased demands for accountability for professional education programs has focused attention on the concept of professional competence. For example, the Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Healthcare looks to the “intrinsic motivation of healthcare providers shaped by professional ethics, norms and expectations” to prevent medical errors despite its recognition that the systems and culture of healthcare provider organizations are essential factors in protecting patient safety.1(p6) Professionals of all kinds are assumed to have the ability to connect solutions to relevant problems, and to possess the expertise that allows them to do this safely and well.2

People desiring entrance to most professional fields face a prolonged period of training. Many of these educational programs rely on first transmitting a body of formal, abstract knowledge related to the profession and later exposing students to practical situations with graduated responsibilities.3 Two assumptions are required in educating professionals: (1) that “human experience is sufficiently regular and repeatable that one can learn from others’ experience,” and (2) that an “order or method to the particular profession can be communicated to the novice and expert alike.”4(p19) Theoretically, a combination of guidance, practical experience, and talent conspires to forge a student into a competent practitioner, and eventually into someone who can develop expertise.5 Yet many programs do not graduate competent practitioners, but instead produce advanced or well-informed beginners.6,7 If this objective seems too modest, consider that one estimate of the time needed to develop competence, meaning the capability of deliberate planning in a conscious way, knowledge of standardized procedures, and the ability to develop long-term vision and handle pressured situations, requires working in the same practice setting for 2 to 3 years.8 Proficiency, the ability to perceive situations holistically, detect deviations from normal patterns, and recognize what is clinically important, can take an additional 3 to 5 years to acquire. An estimate of the time required for acquisition of expertise, someone who no longer relies on rules and/or guidelines and has an intuitive grasp of situations based on tacit understanding, is 10,000 hours.9 Given reasonable time limitations, professional education programs “can only hope to begin the process of development from novice to expert.”7(p215)

Systems of abstract and practical knowledge are often taught separately from practice in the professions.9 Evers, Rush, and Berdrow10 comment that students are exposed to a large body of disciplinary knowledge in their professional preparation programs, but may not develop sufficient skills needed for practice of their chosen profession. They may have difficulty “integrating this material to the point where they can solve challenging workplace problems.”9(p24) Twenty years ago, Schön11 commented on what he perceived as a mismatch between professional education and the demands of professional practice with its uncertainty, instability, uniqueness, and value conflicts. Curry and Wergin4 suggest Schön's concern may be overstated; however, they concur that there can be a disconnect between professional skills and the theoretical education taught in most professional schools.

Pharmacy practice has changed its focus from dispensing drugs to providing clinical care for patients, necessitating that pharmacy schools alter their curricular emphases to preparing students to provide pharmaceutical care. This entails developing a patient-centered focus in which pharmacists take responsibility for patients’ outcomes related to their drug therapy, and requires that students learn to think critically, problem solve, communicate well with patients and other healthcare providers, and resolve ethical problems.12 “The challenge of pharmacy education today is to design, implement, and assess curricula that integrate the general and professional abilities that will enable practitioners to be responsible for drug therapy outcomes and the wellbeing of patients.”12(p50)

Assessing Competence

Increasing demands for public accountability in all professions require that health professions schools produce evidence that their graduates have reached at least minimal standards of competence.13 The educational debate over curriculum reform includes an imperative for the development of assessment procedures “that will assure that graduates will be able to practice successfully and contribute to improved patient care in the newly restructured healthcare environment in the United States.”14(p825) Competent pharmacists are able to provide a high level of patient care in a variety of settings. The variability of the pharmacist's role and practice settings render it difficult to assess students’ abilities to perform all aspects of the pharmacist's role and to apply their clinical knowledge in different practice settings. Nevertheless, the responsibility for assessing students’ competency before graduation belongs to the providers of pharmacy education.15

Competence, the set of knowledge, skills, capabilities, judgment, attitudes, and values that entry-level practitioners are expected to possess and demonstrate, is the result of integrative learning experiences in which knowledge, skills, and abilities are applied to practice problems.16 Assessment efforts should not only determine whether students are acquiring the knowledge, skills, and values that faculty and the profession have determined are important,17 but also provide a tool that enables students to visualize the desired level of performance and give them detailed feedback on their actual performance. Palomba and Banta advise that “developing performance assessment measures requires careful thought about what students are expected to know and what competencies they should develop, and also what methods will be used in both teaching and assessment.”18(p117)

A competency-based assessment process measures students’ performance in experiential courses against previously defined standards. Competency performance requires students to apply their knowledge to clinical problems in a realistic context.19 Clinical performance can vary, and an assessment system needs to communicate what levels of performance are acceptable and unacceptable. Furthermore, “a meritorious grading system … communicates standards of performance beyond a mere pass, including recognition of exemplary standards.”13(p673) In comparison to behavioral objectives, competency statements “are sufficiently broad to allow for interpretation that includes the application of a diversity of skills within complex environments,”13(p673) rendering them more suitable for evaluating performance in the clinical setting. Walvoord and Anderson20 advise that establishing clear criteria for grading can help make the process consistent and fair, assist faculty members to grade more consistently, explain expectations to students, and encourage students to participate in their own learning process because they are able to envision performance goals more explicitly. If assessment forms a stimulus for student learning, clearly assessment systems must reward exemplary students and provide incentive for students to achieve beyond the minimum requirements for graduation.

Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiential Program Assessment Forms and Policy

At Virginia Commonwealth University's School of Pharmacy, the culminating year of the doctor of pharmacy program is known as the Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiential (APPE) Program. It currently consists of eight 5-week, full-time rotations in which students work in diverse pharmacy practice settings under the supervision and guidance of qualified pharmacists. The rotations are intended to “provide students with in-depth experiences to acquire practice skills and judgment and to develop, in a graded fashion, the level of confidence and responsibility needed for independent and collaborative practice.”21(p15) The school's Outcomes, Assessment, and Evaluation Committee has responsibility for assessing outcomes and the evaluation of all program activities in the professional degree program pathway. A subcommittee consisting of 3 clinical pharmacy faculty members and 1 education specialist who chairs the Assessment Committee was charged with reviewing and revising the school's existing assessment instruments for the experiential program in fall 2001. The subcommittee's opinions were that the existing forms were cursory and did not allow for detailed assessment of students’ competence in performing clinical responsibilities. They lacked objective criteria, were not competency related, did not require midpoint grading, and provided little guidance to preceptors in grading.

After reviewing assessment instruments from several other pharmacy schools as well as guidelines published by the Accreditation Council for Pharmaceutical Education and the American Association for Colleges of Pharmacy, we decided to develop a competency-based assessment process with detailed grading rubrics. The purpose of creating a new assessment form and policy were to provide faculty members with guidance in assessing students’ performance according to criteria set for graded competencies, provide students with the tools to visualize expected standards of performance, introduce explicit midpoint grading with detailed feedback, achieve better consistency in grading, and reduce grade inflation.

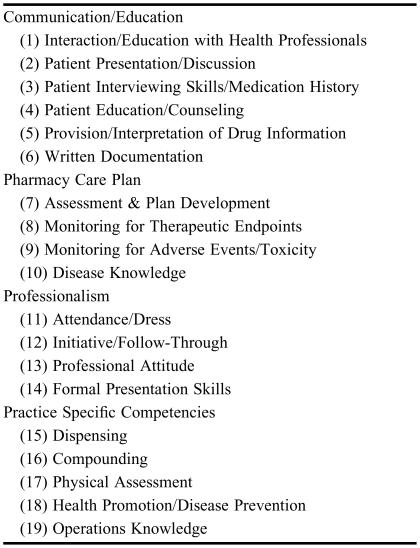

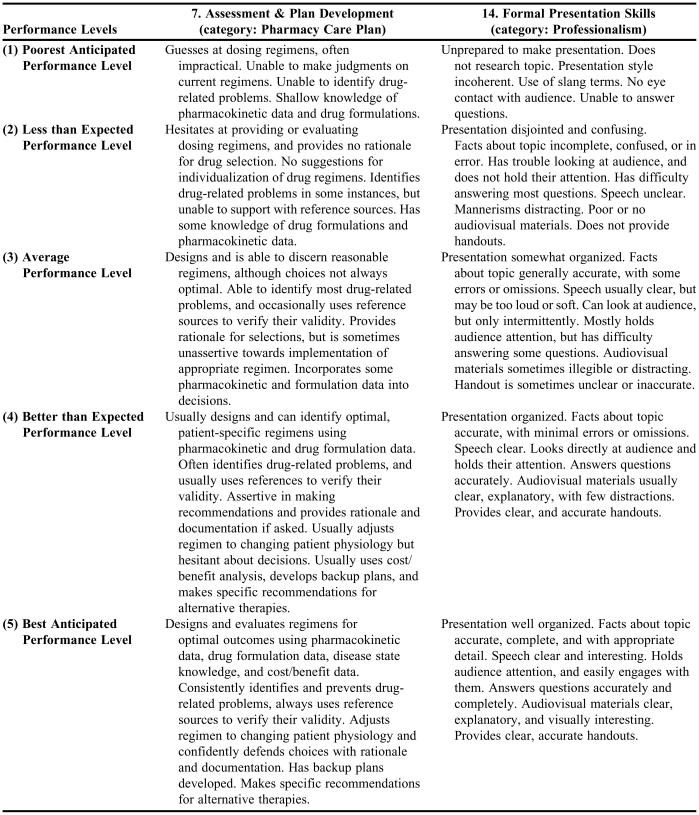

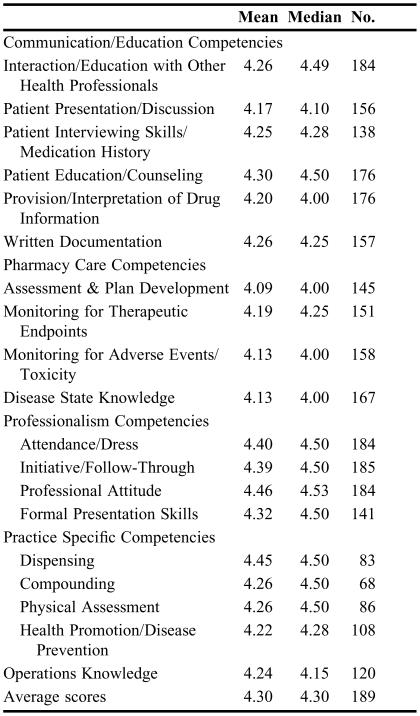

The selection of the competencies was based on (1) Standard 10: Professional Competencies and Outcomes Expectations stipulated by the Accreditation Council for Pharmaceutical Education,20 and (2) educational outcomes articulated by the Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. The result was the selection and description of 19 graded competencies that the subcommittee felt addressed the required pharmacy competencies. These competencies were accepted by Pharmacy department faculty members by a vote. They are grouped in 4 categories: Communication/Education, Pharmacy Care Plan, Professionalism/Initiative, and Practice Specific Competencies (Table 1). The scale for performance levels is: 1 = poorest anticipated performance level, 2 = less than expected performance level, 3 = average performance level, 4 = better than expected performance level, 5 = best anticipated performance level. Detailed expectations were written for each performance level for all 19 graded competencies (see Table 2 for examples). Most experiential rotations are not designed to address all 19 competencies; however, students gained experience in all the competencies by the end of the APPE year because the objectives of the 6 required rotations addressed each of them. Faculty preceptors were also able to evaluate students on additional competencies that were specific to their practice site, although they set their own expectations for these.

Table 1.

Graded Performance Competencies Grouped by Category

Table 2.

Selected Examples of Graded Performance Competencies

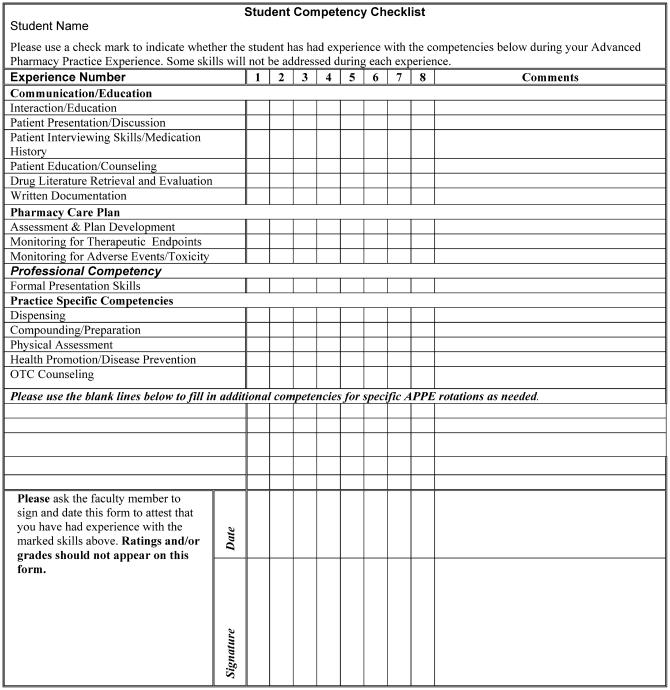

Components of the entire grading process included a student competency checklist containing 15 items, midpoint grading, summary assessment of students’ performance of the graded competencies, and a revised faculty evaluation form. The student competency checklist (Appendix 1) was meant to facilitate the initial discussion at the beginning of the rotation between the student and faculty member regarding what experiences the student had to date, and in what competency areas he/she needed to gain more experience during the APPE. Disease knowledge and 2 professionalism competencies, initiative/follow-through, and professional attitude were not included in the student competency checklist because it was expected that this knowledge and these behaviors will be expressed in all rotations. A third professional behavior, formal presentation skills, was not included because it was expected that all students who complete the required APPE rotations will meet this requirement.

Because the APPE assessment forms provide faculty members with specific criteria by which to evaluate students, it should also serve as a guide for aligning learning activities with outcomes expectations. Effective feedback is specific, clear, and related to specific performance criteria, and should encourage students to reflect on their work in order to improve their performance. Midpoint grading is meant to be an important aspect of the APPE assessment process, and a column was created on the assessment form to record midpoint grades. Faculty members were asked to provide continuous feedback to students, and therefore were strongly encouraged to provide constructive feedback, both positive and negative, on a daily basis. This was intended to direct student learning towards the goals and objectives of each experience. Formal discussions about student performance occurred at both the midpoint and final evaluation.

At the same time the new assessment forms and policy were created, the grading scale for the APPE program was changed from letter grades to honors/pass/fail. Most students were expected to receive a passing score, while a small percentage of students were expected to receive an honors grade. Previously, the supervising faculty members were not discriminating between grades sufficiently and were assigning students unreasonably high grades in the APPE program, thereby inflating students’ grade point averages. There were also reports of faculty members being pressured by students to assign higher grades. In the new scheme, a pass was intended to indicate that the student had achieved the level of competence expected of an entry-level practitioner, meaning the integration of skills, attitudes, and knowledge required for pharmacy practice. An honors grade should have been assigned only to a student when he/she displayed exemplary and outstanding performance. Faculty members were required to provide written justification when they assigned an honors grade. Grades were assigned based on the following scale: honors (average scores of 4.5 - 5.0 for all competencies rated), pass (average scores of 2.5 - 4.49), and fail (average scores of 0 - 2.49).

Drafts of the forms were reviewed by a group of affiliate faculty members in response to the school's invitation, and were also discussed by members of the department within the school that has responsibility for administering and supervising the experiential education program. Faculty comments were taken seriously and their suggestions were incorporated into the forms and grading process whenever possible. The new grading process and assessment instruments for the APPE program were introduced in May 2002. A letter and e-mail introducing the new assessment process and forms were sent to all faculty members supervising our students in the experiential program. Accompanying the letter was a coil-bound copy of the faculty version of the APPE Assessment Booklet that contains program information and the new assessment forms. Adjunct faculty members received the same communications and mailing as full-time faculty members. In addition, the experiential program coordinator made personal contact with many adjunct faculty members. The assessment instruments and grading process were introduced to students at the meeting that begins the experiential program for the year. Students were provided with a coil-bound student booklet containing the same program information and APPE assessment forms. The faculty and student versions of the assessment forms were identical except for the order of the pages. All of the assessment forms were also available to students and faculty members on the school's website and via e-mail attachment.

ASSESSMENT

Faculty and Student Perceptions of the APPE Assessment Forms

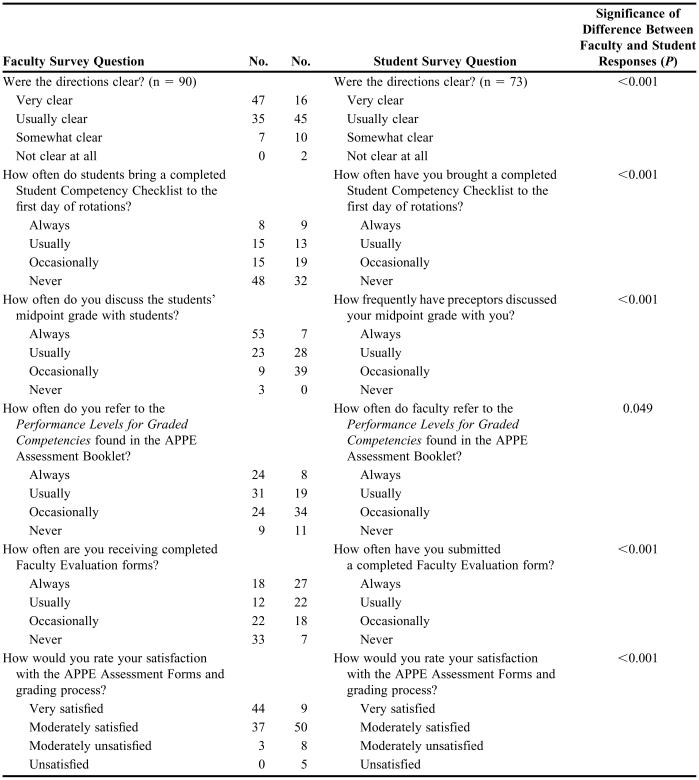

The introduction of the new forms and grading policy was a radical change introduced by the school that was spurred by mandates from the Accreditation Council on Pharmacy Education. Therefore, in March and April 2003, with IRB approval, survey instruments were distributed to faculty and students to gather information regarding each group's perceptions of the grading process, how the forms were being used, and their overall satisfaction with the grading process and the forms. Both the student and faculty survey instruments gathered information on 6 matched questions that inquired about (1) the clarity of the directions, (2) the frequency with which students brought completed student competency checklists to the first day of APPE rotations, (3) whether faculty members were assigning midpoint grades and discussing them with students, (4) whether faculty members were referring to the Graded Performance Competencies descriptions when discussing students’ grades, (5) whether students were submitting faculty evaluation forms to the APPE coordinator, and (6) how satisfied each group was with the APPE assessment forms and grading process. The student survey instrument was distributed and completed by students in the class of 2003 (n = 97) in April 2003 during the last class assembly day, and the faculty survey instrument was mailed in early March 2003 (n = 300). Seventy-four students completed the survey for a response rate of 76%. Ninety faculty members, 14 adjunct and 76 full-time, returned the survey instrument for a response rate of 30%. Chi-square tests were used to compare student and faculty member responses to the survey questions. Chi-square tests were also used to compare adjunct and full-time faculty member responses to the survey questions. The level of significance was set a priori at 0.05. Survey data were analyzed using SPSS, version 11.5. Table 3 presents student and faculty responses to the matched survey questions.

Table 3.

Faculty and Student Responses to Matched Survey Questions

This survey was designed to explore student and faculty perceptions of the assessment forms and grading process, and in general their responses were positive. There was no significant difference between the responses of adjunct and full-time faculty members. However, student and faculty member responses to all 6 of the matched questions differed significantly. Ninety-two percent of the faculty members thought the directions were “very clear” or “usually clear,” while only 83% of the students felt the same. Thirty percent of students indicated they “always” or “usually” brought student competency checklists to the first day of APPE rotations; however, only 25.6% of faculty members reported “always” or “usually” receiving them. Eighty-six percent of faculty members indicated they “always” or “usually” discussed midpoint grades with their students, while their students indicated that faculty members “always” or “usually” did this only 47% of the time. Faculty members indicated that 89% of the time they “always” or “usually” referred to the Graded Performance Competencies when discussing grades with students; however, students observed this “always” or “usually” occurred only 49% of the time. Sixty-six percent of students said they “always” or “usually” submitted faculty evaluation forms, while only 35% of faculty said the students “always” or “usually” submitted the forms. Finally, 96% of the faculty indicated they were “very satisfied” to “moderately satisfied” with the APPE Assessment Forms and grading process, but only 83% of the students indicated they felt that way.

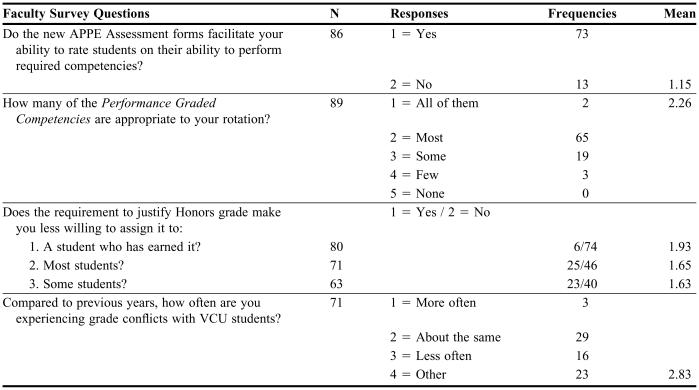

Faculty members were asked an additional 4 questions and their responses are provided in Table 4. Faculty members reported that the new process facilitated their ability to assess students’ ability to perform required competencies. They felt that most of the graded performance competencies were suitable to their practice sites and rotations. The requirement to justify an honors grade in writing did not appear to deter faculty members from assigning them, particularly for students the faculty member felt had earned them. Finally, they indicated experiencing grade conflicts with VCU students “about the same” to “less often” than before the new grading system was implemented.

Table 4.

Faculty Survey Responses to Unmatched Questions

Comments written by faculty members and students were a reflection: (1) of a more comprehensive system of grading, (2) that the new process is more time consuming, or (3) a reaction to the change from the letter grade system to honors/pass/fail. Faculty members described the new system as comprehensive and fair. Other faculty member comments were complimentary of the detailed description of performance levels for the 19 graded competencies. The students reported that they did not believe that all faculty preceptors were using the new forms appropriately, nor did students feel that faculty members were referring to the descriptions of performance levels for the competencies when assigning grades. Others indicated that some faculty members had to be prompted to assign and discuss a midpoint grade. The use of the student competency checklist appeared to have been misunderstood by both students and faculty members. Some students thought it was optional, and others reported that some faculty members were not interested in seeing it or did not know about it. Notably, students reported that achieving an honors grade requires significant effort. The student comments make it clear that more communication between the school and faculty members is needed to achieve better consistency in how the assessment forms and grading process are used.

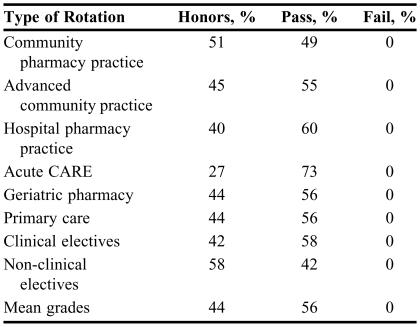

Grades were tracked for the 97 students enrolled in the 9 rotations of the APPE program for the 2002-2003 academic year. The percentage of students receiving passing or honors grades in each type of APPE rotation is reported in Table 5; the mean percentage for honors grades for all rotations in 2002-2003 was 44%; and for pass grades, 56%. Mean and median grades for the specific competencies were also calculated for 21 students (22%) randomly selected from the 97 students (Table 6). The mean score ranged between 4.1 and 4.5, and the overall mean for all 19 competencies was 4.3. Median scores varied between a high of 4.5 and a low of 4.0. Mean and median competency grades in the 2003-2004 academic year were very similar; however, the percentage of honors grades increased to 64%.

Table 5.

Grade Results for the 2002-2003 APPE Program

Table 6.

Mean Scores for the 19 Competencies Measured on APPE Assessment Forms*

1= poorest anticipated performance level, 2 = less than expected performance level, 3 = average performance level, 4 = better than expected performance level, 5 = best anticipated performance level

DISCUSSION

Study Limitations

Differences between the perceptions of faculty members and students of the assessment forms and grading process must be viewed with some caution since the response rates for the 2 surveys differ greatly. The survey instrument consisted of newly developed self-report items that were not validated by direct observation of student and faculty behavior during practice experiences. However, the purpose of the study was simply to inform Assessment Committee members how the forms were being used and determine faculty member and student satisfaction with them. Although students and faculty members were assured that they could respond anonymously, students may have felt that their responses could affect their grades. A web-based survey may have alleviated this concern. Faculty members who responded were quite possibly those most likely to have read and carefully followed the directions. One factor that contributed to faculty members not receiving their evaluations were clerical shortages; the evaluations were only sent to faculty preceptors after the year's experiential program was complete. Inconsistencies in use of the student competency checklist and midpoint grading have improved with further communication and instruction on how to use the assessment tools with both faculty members and students.

Grade Results

The fact that the percentage of honors grades for acute care APPEs was lower than other types of APPEs can be attributed to the acute care APPEs’ difficulty and the fact that the faculty members supervising these APPEs are mostly full-time University faculty members with high performance expectations, and who were either full-time employees of the school or the affiliated teaching hospital. No students failed an APPE during this academic year. Given that the percentage of A grades awarded in the 2001-2002 academic year exceeded 90%, we were moderately successful in reducing grade inflation. The data indicate that on average for the year, all students’ performance ratings were above a 4 (better than expected performance level) for all 19 competencies. Results for the 2004-2005 academic year were similar.

Revision of APPE Assessment Forms

In spring of 2003, the survey results were examined by the Outcomes, Assessment and Evaluation Committee to learn how the grading process and assessment instruments were being used in practice, and what revisions and corrections were needed. In response to the survey results and faculty opinions, the APPE assessment forms were revised for the 2003-2004 Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiential Program. The changes consisted of (1) revising the instructions contained in the student and faculty versions of the APPE Assessment Booklet by adding more headings, breaking the text into shorter paragraphs, and bolding important points as well as the names of the various forms, and (2) introducing a diagram of the APPE Assessment process that illustrates student and faculty responsibilities at the beginning, midpoint, and endpoints of the rotation.

The following spring, the chair of the committee met with selected faculty preceptors who used the forms to solicit further information. In response to faculty comments, further changes for 2004-2005 involved providing more space on the APPE assessment form for written comments for each group of graded performance competencies. This required changing the form from a 1-page format to 2 pages. A minor change was also made to the wording of one of the graded performance competencies to improve its clarity. No changes were made to the student competency checklist or the faculty evaluation form. The director of experiential education now regularly reminds faculty members and students of the importance of midpoint evaluation. In order to graduate, students must submit their completed student competency checklist and faculty evaluation forms. The new documents were sent to faculty preceptors and to the class of 2005 student body in May 2004. Further revisions will be required in the future as the CAPE Guidelines and ACPE Competencies are revised.

Lessons learned include the need for regular communications with both preceptors and students when introducing assessment forms with greater complexity than those to which they are accustomed. Unfortunately faculty members, whether adjunct or full time, have multiple responsibilities and cannot be counted on to read detailed instructions. We learned that assessment messages need to be repeated and conveyed by multiple means. Students also needed to be reminded of program requirements, and this was accomplished during 4 regularly scheduled class assembly days. Grade inflation seems to be a persistent problem requiring constant vigilance and communication with faculty members assigning grades. In hindsight, more communication with both students and faculty members would have been advantageous. The recent addition of an assistant dean of experiential education to our faculty will greatly facilitate this communication in the future.

The goal of any assessment process is the “generation of qualitative and quantitative data that can be used to improve student learning.” 16(p. 21). It is important to create a meaningful assessment plan that has the support of all parties involved. It requires regular consultation with the faculty involved and students whose performance is to be evaluated, as well as recognition of accreditation requirements for pharmacy education. When it is well done, the information generated can be used by students for learning, by faculty for curricular planning, and by accreditation bodies as evidence of the quality of the pharmacy education program. Development and implementation of a competency-based assessment process require a considerable amount of work from dedicated faculty members. With educational institutions under pressure to provide evidence of their graduates’ clinical competence, this effort is a worthwhile investment.

SUMMARY

This article describes the development, implementation, and revision of a competency-based assessment process for the experiential component of a pharmacy education degree program. Faculty member and student perceptions of the assessment process were generally positive. Faculty members needed to be reminded of the importance of asking each student for their student competency checklist and the need to provide students with detailed feedback about their competency performance during midpoint evaluations. We were moderately successful in reducing grade inflation. The new process also provides the school with data that can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of our curriculum in preparing students for practice. This information has already proved valuable in providing outcomes assessment data for regional re-accreditation of the University, and will be helpful in providing documentation for an upcoming self-study to be conducted in preparation for professional pharmacy school re-accreditation.

Appendix 1. Student Competency Checklist

References

- 1.Aspden P, Corrigan JM, Wolcott J, Erickson SM. Patient Safety: Achieving a New Standard for Care. (Institute of Medicine). Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy MM. Inexact sciences: professional education and the development of expertise. In: Rothkopf EZ, editor. Review of Research in Education. Vol. 14. 1987. pp. 133–69. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boshuizen HPA, Schmidt HG, Custers EJFM, Van de Weil MW. Knowledge development and restructuring in the domain of medicine: The role of theory and practice. Learning Instruct. 1995;5:269–89. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curry L, Wergin JF, Associates . Educating Professionals: Responding to New Expectations for Competence and Accountability. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publisher; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bereiter C, Scardamalia M. Surpassing Ourselves: An Inquiry into the Nature and Implications of Expertise. Chicago, Ill: Open Court; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cushing KS, Sabers DS, Berliner DC. Olympic gold: Investigations of expertise in teaching. Educ Horizons. 1992;70(3):108–14. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donald JG. Learning to Think: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publisher; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benner P. From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice. Menlo Park, Calif: Addison-Wesley; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cervero RM. Professional practice, learning, and continuing education: An integrated perspective. Int J Lifelong Educ. 1992;11:91–101. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evers FT, Rush JC, Berdrow I. The Bases of Competence: Skills of Lifelong Learning and Employability. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schön D. Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publisher; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zlatic TD. Redefining a profession: assessment in pharmacy education. In: Palomba CA, Banta TW, editors. Assessing Student Competence in Accredited Disciplines: Pioneering Approaches to Assessment in Higher Education. Sterling, Virg: Stylus Publishing; 2001. pp. 49–70. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andre K. Grading student clinical practice performance: The Australian perspective. Nurse Educ Today. 2000;20:672–679. doi: 10.1054/nedt.2000.0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edelstein RA, Reid HM, Usatine R, Wilkes MS. A comparative study of measures to evaluate medical students’ performance. Acad Med. 2002;75:825–33. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200008000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dolan G. Assessing student nurse clinical competency: Will we ever get it right? J Clin Nurs. 2003;12:132–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banta TW. Assessing competence in higher education. In: Palomba CA, Banta TW, editors. Assessing Student Competence in Accredited Disciplines: Pioneering Approaches to Assessment in Higher Education. Sterling, Virg: Stylus Publishing; 2001. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palomba CA, Banta TW. Assessing Student Competence in Accredited Disciplines: Pioneering Approaches to Assessment in Higher Education. Sterling, Virg: Stylus Publishing; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palomba CA, Banta TW. Assessment Essentials: Planning, Implementing and Improving Assessment in Higher Education. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publisher; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mentkowski M. Associates. Learning That Lasts: Integrating Learning, Development and Performance in College and Beyond. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publisher; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walvoord BE, Anderson VJ. Effective Grading: A Tool for Learning and Assessment. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publisher; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree, Adopted June 14, 1997. Available December 14, 2005 at http://www.acpe-accredit.org/deans/standards.asp.