Abstract

Objective

To establish a successful educational mentor program for the Web-based doctor of pharmacy pathway at Creighton University, School of Pharmacy and Health Professions.

Design

A recruitment process was established and the educational mentor's responsibilities were identified. The roles of faculty instructors, the Office of Information Technology and Learning Resources, the Office of Faculty Development and Assessment, and Web-based Pharmacy Pathway Office as it pertains to the training of educational mentors were clearly delineated. An evaluation process for all key aspects of the program was also put in place.

Assessment

Student, instructor, and mentor evaluations showed overall satisfaction with the program. Persistent areas of concern include the difficulty in motivating students to participate and/or engage in learning with the mentors. Many students remain unclear about mentors' roles and responsibilities. Lastly, in regards to mentors, there is a limited utilization of provided online resources.

Conclusion

The educational mentor program has become an invaluable component of the Web pathway and has enhanced the interactions of students with the content and mentor.

Keywords: Web-based education, PharmD program, quality assurance, mentor, assessment, distance education

INTRODUCTION

Faculty members at the Creighton University School of Pharmacy and Health Professions (SPAHP) approved the implementation of a Web-based pharmacy pathway in 2000, with the first students enrolled for fall 2001.1 The first class graduated in May 2005. The SPAHP implemented a nontraditional post-BS doctor of pharmacy program in 1994 that utilized technology as part of the didactic training; thus, many faculty members had experience with asynchronous education. Prior to the implementation of the Web-based pathway, in the 2000-2001 academic year, the SPAHP required all entry-level students to have a laptop computer for classroom use. The Office of Information Technology and Learning Resources, which oversees all SPAHP technology needs, has grown to include 15 individuals whose main responsibility is to support the infrastructure required for distance education. Faculty members involved with the Web-based pathway are provided with technology training to deliver their course materials effectively online. In addition, many faculty development seminars have been offered by the Office of Information Technology and Learning Resources and the Office of Faculty Development and Assessment to support and prepare faculty members for facilitating online student learning.

The Web pathway differs from the campus pathway in that students participate in didactic course work year-round. The overall didactic course requirements for both pathways are identical. All didactic classes are conducted over the Internet using print, audio, and/or video materials. Students are required to return to campus during the summer for laboratory coursework, annual assessments, and select clinical experiences, which are administered in a condensed manner over a 1- to 2-week period. The final year consists of completing advanced pharmacy practice experiences, which may be at sites near the student's homes.

The Web-based pharmacy pathway is highly dependent on technology and online learners have stated in several research articles that they prefer a mentor/facilitator whom they can contact to assist with a variety of issues including course content, logistics, and technology. For example, Masie2 conducted a survey on the role of trainers in the e-learning experience. Analysis of responses from 2119 participants indicated that 88% wanted a trainer assigned to e-learning experiences. Furthermore, 62% of respondents indicated they were more likely to select e-learning courses that included a trainer. Other research findings have similarly emphasized the importance of interaction between the student and instructor in online courses.3-6

The 4 types of interactions identified in online education include: learner-content, learner-learner, learner-instructor (mentor), and learner-interface.7-10 Fredericksen and associates11 observed a positive relationship between the amount of student interaction with their instructor and their level of perceived learning. In addition, students indicated that timely, prompt feedback from their instructor contributed to positive perceptions of student-instructor interactions.12

In our Web-based program, student demographics over a 4-year period demonstrated that the majority were nontraditional, working full-time or extensive hours, location-bound, and pursuing second or third careers. These extracurricular activities and responsibilities have challenged us to deliver a high-quality distance education program. Therefore, for the Web pathway, educational mentors were incorporated to help facilitate student-learning, decrease the workload on the instructors, and develop a learning community in each course. The purpose of this paper is to describe, in detail, the structure and quality assurance process of the educational mentor program, including a critical self-reflection on 4 years of program implementation.

DESIGN

Structure

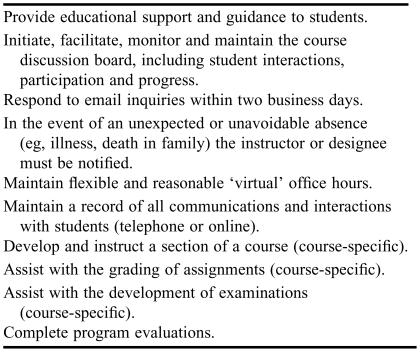

When the decision was made to hire mentors, a focus group chaired by the associate director of the Web pathway worked on defining the title of the individuals who were to be hired. Although many terms were used, including online trainer, tutors, and teaching assistants, the focus group decided on the official term of educational mentor. The term is professional and clearly indicates the significant role these individuals would be playing in the course environment. The main responsibility of the educational mentor was to complement the educational needs for each course in the curriculum as identified by course instructors. The educational mentors are required to collaborate with the instructor to ensure a high-quality learning experience for the Web-based students through participation in discussions, answering routine questions, explaining the content, tracking student progress, and performing other duties as assigned by the instructor, including grading. Communication with the students is facilitated by e-mail distribution lists, synchronous conferences, and by course discussion boards. Thus, the educational mentors enhance most of the identified types of interactions in distance education mentioned above. The most common responsibilities as identified by the instructor are summarized in Table 1. The responsibilities of the educational mentor are also described in detail in the mentor handbook, which is available on the mentor web site (http://pharmacy.creighton.edu/mentors).

Table 1.

Educational Mentor Responsibilities as Assigned by Course Instructors in a Web-based PharmD Degree Pathway

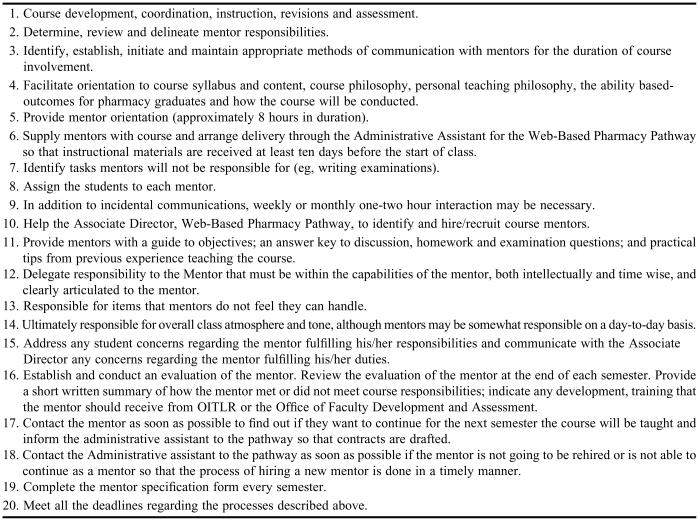

The focus group clearly identified the roles and responsibilities of the instructor relative to the use of mentors to minimize confusion and enhance the impact on the educational process (Table 2). Each instructor is asked to complete a mentor specification form, which serves as a template for determining educational mentor needs and responsibilities. (The mentor specification form is available from the author by request). The form is meant to help the instructor reflect on how the educational mentor will meet the specific needs of the course; thus, the form is also important in recruiting the right mentor and assessing his/her performance. In addition, some faculty members have developed an activity grid13 that lists all of the course activities and then indicates the role that the educational mentor will play helping the students meet the expected outcomes from those activities. The mentor specification form has proven to be a useful tool.

Table 2.

Responsibilities of Instructors for a Web-based PharmD Degree Pathway

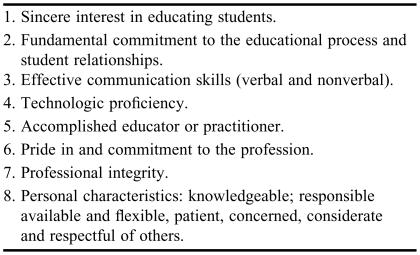

Before recruiting the educational mentors, the focus group, with input from faculty members, agreed on attributes that educational mentors should embody and model (Table 3). These attributes mirror the minimum characteristics required for the majority of courses in the PharmD curriculum. Students' narrative evaluations of the mentors were later analyzed to ensure that students perceived that the mentor demonstrated the attributes described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Educational Mentor Attributes

Recruitment

The mentor recruitment process was coordinated by the Associate Director and Administrative Assistant for the pathway. The majority of the mentors recruited held faculty positions at other institutions and several of them had taught at least one course online. In the second year of the pathway, a mentor coordinator was hired to manage the educational mentor program, although after about 2 years the responsibility for educational mentors was returned to the associate director. The recruitment process progressed smoothly during the third and fourth years because of the hard work put forth the first 2 years of the pathway to identify and recruit quality educational mentors.

When the program was started, recruitment of the mentors was initiated with a letter to alumni and an advertisement in Mortar and Pestle, the Nebraska Pharmacists Association's official journal. Emphasis was placed on identifying mentors for the first semester courses. In addition, word of mouth by faculty members was utilized to identify candidates locally and during national professional meetings. Within 3 weeks, more than 60 applicants indicated interest in the educational mentor program. An advertisement placed in Science online was successful in recruiting more than 50 applicants with mostly PhD qualifications for the various basic science courses. Applicants were also recruited from e-mails sent out to listservs whose audience was related to specific courses needing mentors. Candidates were asked to e-mail a letter of interest to the associate director of the Web-based pharmacy pathway, and upon receipt, they were sent the application form to be completed.

Each candidate was required to submit an application and curriculum vitae. The application could be completed online at the mentor web site (http://pharmacy.creighton.edu/mentors). The instructors have been encouraged from the beginning to identify their own educational mentors, either colleagues, graduate students, or alumni with whom they were familiar. Educational mentor qualifications included individuals with BS Pharm, PharmD, MS, MD, or PhD degrees. PharmD students and MS/PhD graduate students also have been allowed to participate based on instructor recommendations (eg, upper class PharmD students have been used as mentors in courses such as Pharmacy Calculations).

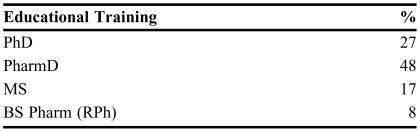

The number of mentors hired per course is based on a ratio of one mentor per 20 students per 3 credit hours. The Web pathway class size has ranged from 50-60 students since its inception. Based on initial experiences, some faculty members have found it more effective and efficient to utilize fewer educational mentors per course, rather than the number suggested by the ratio. The current percentage of educational mentors by degree is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Level of Education Attained by Mentors Recruited for the Web-based PharmD Degree Pathway, N = 48

Reimbursement

In accordance with Creighton University's faculty handbook, educational mentors are employed on a temporary, part-time basis as independent contractors. The period of employment is based on course involvement and duration (ie, as determined by the instructor), which typically extends for the duration of the stated semester. Payment will only be provided during periods of active course involvement. Reimbursement is based on an hourly wage, education and professional training, course credit hours (eg, reimbursed for 3 hours per week for a 3 credit hour course), and semester length (per SPAHP calendar). Additional monies are provided for course orientation and Internet service provider connection fees. The University provides malpractice insurance, protecting educational mentors in case of liability issues that may occur during interactions with students while performing responsibilities as defined by the instructor. The mentor handbook, which includes a description of all aspects of the mentor program described in this manuscript and the history of Creighton University, the history of the Web pathway, and welcome letters from the Dean, Director, and Associate Director of the Web pathway, is sent to educational mentors with the contract.

Training

Training of the educational mentors is essential to ensure their positive contributions to all aspects of interactions discussed above that are critical to online education and to the goals of the mentor program. Training is accomplished by several individuals and offices within the School. Orientation is provided to each educational mentor by the instructor, whether new or returning. During the initial orientation, 8 hours of training is provided to review issues such as orientation to course syllabus and content, course philosophy, personal teaching philosophy, the ability-based outcomes for pharmacy graduates, and how the course will be conducted. For returning educational mentors, 2 hours are allocated to review any changes to the above since the last course offering. Training is accomplished face-to-face, online, via telephone, or by e-mail.

As part of the commitment to providing professional development for educational mentors participating in the Web pathway, the Office of Faculty Development and Assessment was asked to contribute to the professional development of educational mentors. The initial step in engaging mentors in faculty development activities begins with making sure we see the mentors as a visible part of our faculty community. The initial step in this plan was an introductory letter informing them of the development resources in the School and University. A critical second stop was consistent access to faculty development information that is routinely sent electronically to faculty members. This was easily done just by including the mentor distribution list in our faculty development group e-mail system. This ensures that mentors receive articles and resource materials on the Office of Faculty Development and Assessment web site, as well as invitations to future development sessions.

The Office of Information Technology and Learning Resources also plays an integral role in the process of mentor training related to technology and online teaching. The more comfortable the educational mentor is with the technology, the better his/her experience and contribution will be. This will also have a positive effect on the learner-interface interaction, since they can lessen negative student experiences related to technology, web site organization, accessing information on the course web site, etc. The Office of Information Technology and Learning Resources provides educational mentors with an introductory letter at the start of each semester that includes an overview of the development activities planned for the upcoming academic calendar year. The Office of Information Technology and Learning Resources arranges for access to the Office's web site and the CULearn web site which contains online tutorials for course-specific software and hardware. Examples include tutorials on Front Page, Blackboard, Excel, Outlook, Conferencing Server, etc. Since 2002, the Office of Information Technology and Learning Resources has also included educational mentors on e-mail distributions of professional development information, maintained an educational mentor distribution list, provided educational mentors with a copy of the technology handbook, and provided orientation and training to specific technology required for courses (on an as needed basis). The Office of Information Technology and Learning Resources has also been involved in surveying all new mentors to determine information technology competency in order to facilitate the development of appropriate training sessions. Competencies assessed include:

Proficiency with a personal computer running Microsoft Windows XP or later, Office 2003 (Word, PowerPoint, Excel, and Access);

Proficiency with e-mail (eg, sending attachments, using folders, filters, etc);

Use and management of a discussion board;

Familiarity with different course environments (eg, FrontPage, Blackboard).

Educational mentors also have access to the Creighton University Health Science Library System and may procure books and supplies through the CU bookstore at discounted rates. Other training programs made available through the mentor web site, include: handbooks (mentor and technology), a discussion board (to encourage sharing of ideas, concerns, teaching strategies, resources, etc), and links to the Office of Information Technology and Learning Resources training web site, Faculty Development web site, and other online education resources. Mentors are also encouraged to utilize the Teaching and Learning Online web site and review a number of references for helpful tips pertaining to online communication and education. Some of the topics reviewed include the effective use of e-mail, discussion groups, and online tutoring (roles/responsibilities).

ASSESSMENT

The assessment process for the mentor program has been ongoing and dynamic, involving all the key players including educational mentors, instructors, students, Office of Faculty Development and Assessment, and Office of Information Technology and Learning Resources. During the first 2 years of the program, a great deal of time was spent ensuring the logistical aspects of the program were developed, including assessment instruments. Formalization of the quality assurance processes, including data collection methods, were developed and implemented; however, formal analysis was not completely undertaken until the third year of the program. Despite this delay, all identified issues and concerns were addressed as they arose.

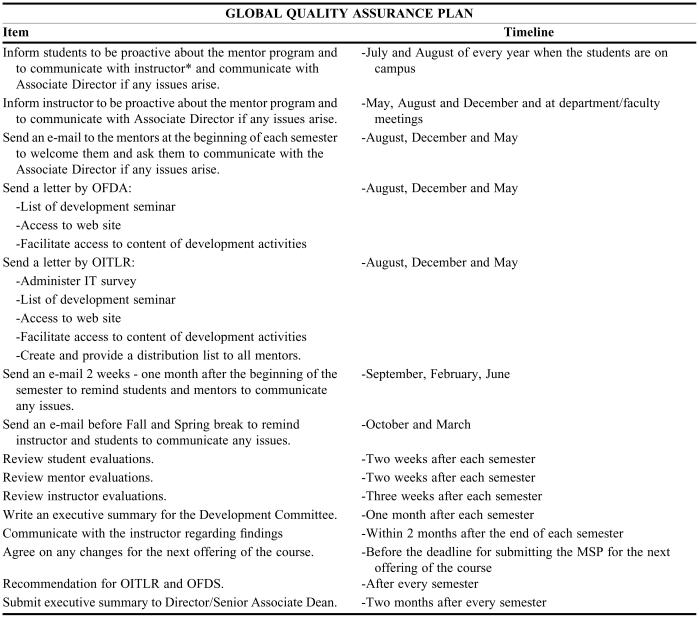

As mentioned previously, the global quality assurance plan, which includes all key players, was developed the first year of the pathway. Appendix 1 provides an overview of the global quality assurance plan in place since fall semester 2004. All components are reviewed every semester with modifications made according to input from key players, collected data, and student focus groups.

During the first year of the pathway, 5 evaluation forms were developed for the following areas: mentor evaluation of program, instructor evaluation of program, instructor evaluation of individual mentors, student evaluation of program, and student evaluation of individual mentors. Program evaluation included: process (recruitment, orientation, and guidance/support); communications between mentor, instructor, and students; technical support; and administrative issues (interaction with associate director, administrative assistant, contracts, payroll, etc). Individual evaluations were critical to assess the effectiveness of the educational mentor and to provide constructive criticism for the purpose of professional development and decisions regarding return for subsequent course offerings. The questions asked on the individual and program evaluations are similar, each being geared towards the intended audience.

In the summer of 2004, the 5 forms were combined and modified into 3 forms (available from authors): instructor evaluation of the mentor and the program, student evaluation of the mentor and the program, and mentor evaluation of the program. All of the evaluation forms except for the instructors' are made available online via QuestionMark to provide anonymity and facilitate analysis. The instructor forms are delivered to instructor mailboxes as hard copy because it was felt that this provides a better response rate.

As stated earlier, student focus groups are held each summer when Web-pathway students take classes on campus. Students are asked to express any concerns regarding the pathway and the mentoring program. The data and information collected from the evaluation forms and the focus groups is then reviewed for confirming themes or issues, and thereafter an executive summary is generated. An action plan for each item is developed and addressed with key players before the start of each semester. Modification to program policies and procedures, evaluation forms, and the quality assurance process are made and implemented accordingly, as are decisions regarding mentor return and other course-specific issues.

The subsequent section will provide an overview of the data collected for the academic calendar year 2004-2005 as it reflects complete implementation of quality assurance measures. This academic year was also chosen because it includes instructor and educational mentors who have been involved with the Web pathway for more than 1 course offering and contains 3 didactic years of the program and all Web classes (Rx2005-Rx2008). The analysis of these data was provided as an executive summary to members of the Web Pathway Development Committee, whose input was sought before action plans were initiated. An outcome for each action was identified and a follow-up plan was established (Table 5).

Table 5.

Results of Evaluation of Mentors Who Participated in a Web-based PharmD Degree Pathway (N = 19)

Instructor of Record Evaluations

The PharmD program offers a total of 28 required courses, all but 3 of which are currently utilizing mentors. During the 2004-2005 academic calendar year, all instructors (n = 25) completed the educational mentor and program evaluation forms. During this past year, including all courses taught during the fall, spring, and summer semesters, the instructors scored their mentors at an average of 4.9 out of 5 for all 11 questions on the form, based on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree). As noted earlier these forms (available from author) contain questions related to the educational mentor meeting his/her roles and responsibilities, communications, and facilitation of student learning. The instructors' formative data illustrate great satisfaction with the mentor program and the support received from the Web pathway office. However, despite the compelling nature of these data, the feedback obtained from instructors in some courses is incongruent with student perceptions.

Student Evaluations

Per review of student evaluation forms, including narrative comments, the educational mentors are facilitating student learning in 65% of the courses (n = 25). Frequently reported comments by the students included: “role model,” “very concerned,” “highly professional,” “very helpful,” “positive,” “very prompt,” and “excellent explanations.” Per student feedback, 35% of the courses were identified as “red flag,” ie, requiring follow-up with the instructor to either, reevaluate mentor responsibilities, selection, and/or number. These recommendations were based, for the most part, on the large cohort of students who were neutral (per the 5-point Likert scale) about the role of the mentor. There were no class- or semester-specific issues or trends related to the aforementioned issues. As noted earlier, because of the lack of communications between instructor and mentor and a lack of a clear idea regarding mentor responsibilities, concerns regarding the mentor program were the highest among students in the first year; however, improvements were noted in subsequent semesters.

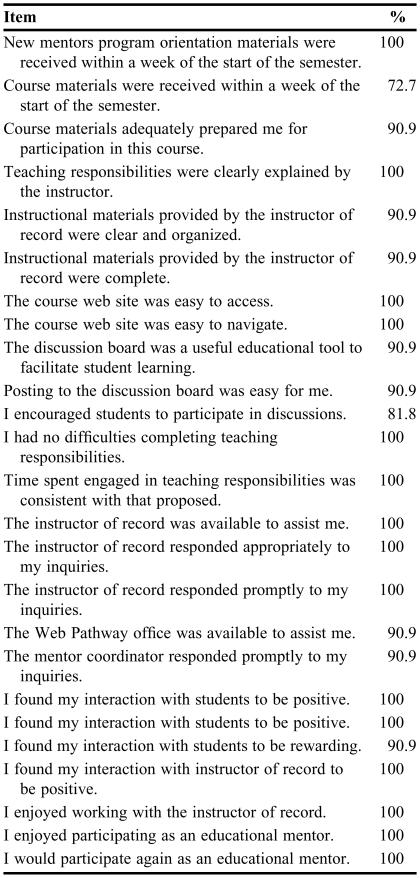

Mentor Evaluations

The results from mentor formative evaluations of the program are summarized in Table 6. Ninety percent or more of the mentors answered strongly agree or agree on the majority of the questions related to the program, their interaction with students, and the instructors. No mentors disagreed or strongly disagreed regarding any of the items; however, 18% and 27% of the mentors were neutral about the usefulness of the mentor and technology handbooks, respectively. Approximately 50% of the mentors were also neutral regarding the usefulness of the mentor web site, the online teaching references, and the mentor discussion board. The neutral responses may be secondary to experience since 80% of the mentors had been involved with the program for more than 1 academic year. Regardless, more effort will be put forth by the Associate Director to encourage mentors to utilize these resources. Focus groups with instructors and mentors may also prove useful in determining why these resources are not being fully utilized as well as in identifying additional resources.

Narrative comments from the mentors support the formative data collected. Mentors clearly identify the good and positive interactions with students and that the “students display high level of professional curiosity and a genuine interest.” They also describe their interaction with the instructor as “rewarding and very professional” and that the instructor was “amazingly organized,” did a “fantastic job,” and were “excellent.” As for the program, they agreed that the program was “well organized” and that problems were “addressed quickly.”

DISCUSSION

The mentor program has been an invaluable component of the Web pathway and has helped enhance the interactions of the students with the content and mentor. Following the first 2 years of setting up all the logistical aspects of the pathway and the mentoring program, most if not all of the instructors have adapted well to incorporating educational mentors in their courses, and have clearly indicated that they find the mentors to be helpful in facilitating student learning, decreasing faculty workload, and meeting curricular goals. The mentor specification form has been a valuable tool in helping instructors concentrate on clearly describing and delineating mentor roles and responsibilities, and to relate this to issues of student outcomes, workload, and communication. The students perceive great value in the overall contributions provided by the mentors. However, there are still variations among courses which are to be addressed by the respective instructors.

The first year of the program was particularly difficult because this was a work in progress and all the key players (educational mentors, instructors, and students) were not clear on how the process would work. Many instructors were uncertain about how to best utilize educational mentors in their courses. Communication between the educational mentor and instructor often was suboptimal. Despite several faculty members being familiar with distance education through participation in the nontraditional program, this did not necessarily help since it involved mailed materials (eg, paper, video) at the beginning rather than online teaching. In addition, the School of Pharmacy and Health Professions hired new faculty members to specifically teach in the Web pathway, many of whom required time to assimilate with the school and educational process. Similarly, most of the educational mentors were ambiguous about their roles and responsibilities. Also, the students were uncertain of educational mentor roles and responsibilities, and how to utilize them to maximize learning.

Most instructors have hired individuals with whom they are familiar. Alumni constitute 16% of the mentors who have participated in courses throughout all 3 years of the didactic curriculum. Since 2002, instructors have retained the same educational mentor approximately 80% of the time, which has provided consistency within individual courses and has allowed for the professional development of these educational mentors so that responsibilities are performed more effectively and efficiently. Now that the pathway is well known and received among the professional pharmacy education and practice communities, unsolicited requests are often received at local and national professional meetings to be part of the educational mentor program. In addition, many members of the first Web-based graduating class have expressed an interest in participating as an educational mentor, some of whom have already submitted applications. Instructors will be encouraged to utilize as many of these graduates as possible, since their experience serves as a great asset for students and the pathway.

Since fall semester 2004, all instructors have been involved in the Web pathway degree program and have taught their respective courses several times. Most now have a better idea on how to best utilize educational mentors and articulate this information clearly on the mentor specification form and course web site. In addition, faculty members have shared their experience with peers during department meetings and faculty retreats. This has helped faculty members who are new to the process better coordinate efforts with their educational mentors. The Associate Director, and before him the Mentor Coordinator, have also provided seminars for the faculty about the mentor program and how best to utilize educational mentors. Suggestions provided included creating a web page about the educational mentor on the course web site that included a picture of the mentor and a description of the mentor's role and responsibilities. Further, instructors have been encouraged to introduce the educational mentor to the students at the start of the semester via e-mail, clearly describing expectations and responsibilities of both the educational mentor and instructor.

One indicator that the instructors have begun to feel more comfortable with the process is that the number of mentors required per course has decreased since the initiation of the pathway. There have been 3 courses in which the instructor felt that the use of educational mentors was not necessary. In each case the instructor had been hired specifically to teach online and felt that he/she could facilitate student learning sufficiently without the assistance of a mentor. Other observed changes include 3 courses in which the mentor requirement decreased from 3 to 1, 1 course in which mentor requirements decreased from 3 to 2, and 3 courses where mentor requirement decreased from 2 to 1.

During the 2004-2005 academic year, and as a result of the (2003-2004) quality assurance plan, better communication with the students, instructors, mentors, Office of Faculty Development and Assessment, and the Office of Information Technology and Learning Resources was identified as one of the areas for improvement. This is essential for the success of the mentoring program. Therefore, all key players were reminded at the beginning of the semester and throughout the semester to be proactive about communicating issues in a timely manner and to actively contribute to the evaluation process. This has certainly improved on the data collected from all key players.

The faculty input in the 2004-2005 academic year regarding the mentors in general and the mentoring program in particular was encouraging and consistent with findings from previous years. One major emphasis for the Web pathway was for faculty members to document parity between the learning and performance of students in the campus-based pathway vs. that of students in the Web-based pathway. Many instructors have documented overall parity between the 2 student cohorts.1,13 Some instructors have also demonstrated how educational mentors have contributed to student learning and performance, which further emphasizes the important role of the program13 and provides evidence that mentors do contribute to enhancing and optimizing learner-content and learner-mentor interactions.

Based on the student evaluations of mentors, the Associate Director communicated directly with instructors in courses where a “red flag” was identified. These communications were used to support decisions regarding the return of 1 mentor, to decrease the number of mentors in 3 courses, and to change the responsibilities of the mentors in 2 courses. For the latter, it was agreed that the chosen mentor candidates would be identified as teaching assistants so that the students recognize that they are not directly involved in facilitating student learning and that they are only evaluated based on the specified responsibilities.

In general, mentor evaluations of the program were very positive. However, the high percentage of neutral responses regarding the usefulness of the mentor web site, the online teaching references, and the mentor discussion board may be secondary to experience since 80% of the mentors had been involved with the program for more than 1 academic calendar year. Regardless, more effort will be put forth by the Associate Director to encourage mentors to utilize these resources. Focus groups with instructors and mentors may also prove useful in identifying reasons why these resources are not being fully utilized, as well as in identifying additional resources.

One concern that some mentors clearly identified is the difficulty of motivating student participation. There were a number of issues related to this, the most important of which was time constraints, which has been identified in the literature as being a barrier to interaction with course content.14 As one mentor stated, “I have to remind myself that this is not the only course they are taking.” Another issue was whether the course required more discussion and interactions between students and mentors and whether a clear and concise reward structure was assigned to this. Swan15 demonstrated that student interactions with instructors were positively correlated with the percentage of their course grade that came from participation in course discussions. Also evident from instructors and mentors' narrative comments was that student participation in discussions appeared to be based on individual interest as well as an awareness of the impact participation had on their course grade. Therefore tips for enhancing student participation in online discussions are sent to instructors and mentors before the start of each semester. Additionally, the educational mentors will continue to be asked to be proactive, facilitate but not lead the discussion, and whenever appropriate and possible, provide practical applications to the knowledge that the students are trying to master. Further, the instructors will continually be encouraged to identify course objectives and outcomes for discussion, and clearly articulate the evaluative process for mentors and students.

The school has been successful in hiring quality educational mentors to help facilitate student learning. The Associate Director, in coordination with the Web-based Pharmacy Pathway Development Committee, works diligently to maintain the mentor pool and increase satisfaction. Based on experiences from the first 4 years of the program, an annual symposium to educate instructors on how to best utilize educational mentors and improve the effectiveness of those already involved with the program is under consideration. The instructors and mentors already involved with the program will be asked to participate and present. The symposium will be video recorded for distribution to instructors and mentors unable to attend the live programming. In addition, establishment/creation of a Mentor of the Year award is being considered to be awarded to the individual voted by each web class as the most outstanding mentor.

The Web-based pharmacy pathway accommodates a specific group of students. Therefore, it is essential to strive to meet all the needs of those enrolled, including the important role educational mentors play in conveying curricular objectives. The Associate Director works very closely with the Web-based Pharmacy Pathway Development Committee, the instructors, the students, mentors, the Office of Faculty Development and Assessment, and the Office of Information Technology and Learning Resources to make sure that the mentor program is appropriately addressing curricular needs. The quality assurance plan has effectively helped to streamline the process and identify the majority of the issues and concerns identified by all involved so that immediate measures can be implemented in subsequent semesters to optimize student learning and satisfaction.

Mentors have consistently found the process very rewarding and many have commented on the professional attitudes of the students. They also seem to have developed collegial and professional relationships with the instructors. The School has been fortunate in being able to recruit an excellent pool of highly qualified mentors who are committed to the educational process. Having recently graduated the inaugural Web-based class, it is anticipated that these alumni will be a great asset to the continued success of the mentor program and students in future years.

SUMMARY

The successful educational mentor program for the Web-based doctor of pharmacy pathway at Creighton University was built through these key instructional design components: 1) building a recruitment process, training and development structure for mentors; 2) establishing a coordination and communication process with other school committees and offices; 3) collection of data and feedback on program implementation, and 4) using the responses to continue to enhance and refine the educational mentoring program. Although the Web pathway continues to challenge the faculty members and School in many ways, however, whether it is the mentor program or other aspects of the pathway, the staff, faculty members and administration continue to commit the time, effort, and resources needed to ensure a high quality learning experience for the students.

Appendix 1. Global Quality Assurance Plan

REFERENCES

- 1.Malone PM, Glynn GF, Stohs SJ. The development and structure if a web-based entry level doctor of pharmacy pathway at Creighton University Medical Center. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(2) Article 46. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Masie E. Roles and Expectations of e-Trainers. Learning Decisions Interactive Newsletter. April 2000. Available at: http://www.masie.com/masie/researchreports/fromLD/LDApr00.htm. Accessed on September 1, 2005.

- 3.Billings DM, Connors HR, Skiba DJ. Benchmarking best practices in Web-based nursing courses. Adv Nurs Sci. 2001;23:41–52. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200103000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyle DK, Wambach KA. Interaction in graduate nursing Web-based instruction. J Professional Nurs. 2001;17:128–34. doi: 10.1053/jpnu.2001.23376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. King JC, Doerfert DL. Interaction in the distance education setting. 2000. Available at http://www.ssu.missouri.edu/ssu/aged/naerm/s-e-4.htm. Accessed on September 2005.

- 6.Meyen E, Lian CHT. Developing online instruction: one model. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabilities. 1997;12:159–65. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thurmond VA, Wambach K. Towards an understanding of interactions in distance education. Online J Nurs Inform. 2004;8(2):8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehrlich DB. Establishing connections: Interactivity factors for a distance education course. Educ Tech Soc. 2002;5:48–54. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rovani AA. A preliminary look at the structural differences of higher education classroom communities in traditional and ALN courses. J Asynchronous Learning Networks. 2002;6(1):Article 3. Available at: http://aln.org/publications/jaln/v6n1/v6n1_rovai.asp. Accessed on September 1, 2005.

- 10.Chen GD, Ou KL, Liu CC, Liu BJ. Intervention and strategy analysis for Web group-learning. J Comp Assisted Learning. 2001;17:58–71. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fredericksen E, Pickett A, Shea P, Pelz W, Swan K. Student satisfaction and perceived learning with on-line courses: Principles and examples from the SUNY learning network. J Asynchronous Learning Networks. 2000;4(2):Article 1. Available at: http://aln.org/publications/jaln/v4n2/v4n2_fredericksen.asp. Accessed on September 1, 2005.

- 12.Thurmond VA, Wambach K, Connors HR, Frey BB. Evaluation of student satisfaction: Determining the impact of a Web-based environment by controlling for student characteristics. Am J Dist Educ. 2000;16:169–89. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alsharif NZ, Roche VF, Ogunbadeniyi AM, Chapman R, Bramble JD. Evaluation of Performance and Learning Parity Between Campus-based and Web-based Medicinal Chemistry Courses. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(2) Article 33. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atack L, Rankin J. A descriptive study of registered nurses' experiences with web-based learning. J Adv Nurs. 2000;40:457–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swan K. Virtual interaction: design factors affecting student satisfaction and perceived learning in asynchronous online courses. Dist Educ. 2001;22:306–31. [Google Scholar]