Abstract

Objectives

Describe the planning and implementation of a pilot peer review system, assess factors related to acceptance by faculty and administration, and suggest ways to increase the number of faculty members reviewed and serving as reviewers.

Design

A faculty-driven process was used to create a model for peer review. Faculty members completed a survey instrument with open-ended responses for indicating reasons for participation or nonparticipation, components of the evaluation process that they would like to see changed, and what they found most helpful or insightful about the process of peer review.

Assessment

Faculty acceptance of and satisfaction with the peer review process is attributed to the development and implementation process being faculty driven and to peer reviews not being required for promotion and tenure decisions. Faculty members who were reviewed stated that the process was helpful and insightful and would lead to better teaching and learning.

Conclusion

A successful faculty peer-review process was created and implemented within 6 weeks. All of the faculty members who chose to be peer reviewed or serve as reviewers reported satisfaction in gaining insights into their teaching, learning innovative approaches to their teaching, and gaining confidence in their teaching pedagogy. Techniques for achieving 100% participation in the peer review process should be addressed in the future.

Keywords: peer review, faculty development, assessment

INTRODUCTION

Virtually every school of pharmacy in the United States uses student evaluations to assess course and teacher effectiveness, while only about 50% utilize some form of peer evaluation among faculty members.1 One primary reason for lack of emphasis on peer review is the lack of guidance for faculty members who wish to do the work of peer review well.2 Student evaluations of faculty members are often used for both formative and summative purposes ranging from self-development to evaluation for tenure and promotion.1 However, using student evaluations to the exclusion of additional methods of teaching assessment may not be optimal.3 Although student evaluations are reliable and valid in assessing teacher effectiveness,4-6 they can be biased.3,7-10 Studies suggesting possible bias in student evaluations demonstrate that the higher the grades students receive, the higher the students rate their teachers. For example, Kidd and Latif analyzed a total of 5,399 individual student evaluations from 138 courses taught over several years at one school of pharmacy.3 The authors concluded that students' grade expectations for a course and how they evaluated the course were highly correlated (P < 0.001). If subsequent investigations in schools of pharmacy confirm these results, it is probable that many faculty members may lower their grading standards to obtain more favorable student evaluations. In fact, Kerr provided evidence that employees in many diverse workplace settings often gravitate toward behaviors that are rewarded by the organization, often to the exclusion of those behaviors that are not rewarded.11 Thus, it seems plausible that if student evaluations are summative and promotion depends on good evaluations, many faculty members might “grade easier” to obtain higher evaluations. One way for schools of pharmacy to optimize teacher evaluations is to incorporate multiple assessment methods into the process.

One triangulation of assessment methods includes self-evaluation and peer evaluation, in addition to student evaluation. Based on this rationale, the objective of this investigation is to describe the planning and implementation of a pilot peer review teaching project. Although a significant number of schools use peer evaluation, the authors know of no previous studies in schools of pharmacy that have described the peer review process and implementation.1

METHODS

Prior to beginning our research, this study was approved by the Human Subjects Review Board of Shenandoah University. The prevailing opinion of the faculty of The Bernard J. Dunn School of Pharmacy at Shenandoah University was what Seldin (1998) emphasized: student ratings of teaching performance “are distrusted by many, misused routinely, and are only part of the evidence needed for a thorough assessment of teaching.”12 The faculty and administrators eagerly participated in the formulation and implementation of a peer-review process.

Time, effort, and commitment to planning were essential and would lead to an efficient and effective process.6 With approval from upper administration, 30 faculty members at the summer retreat discussed the need for an additional teaching evaluation method such as peer review to use in conjunction with student evaluations to help develop and assess faculty teaching. Because faculty member buy-in was deemed critical to the success of this project, one of the authors conducted a workshop at the school's annual retreat during the summer of 2004. Subsequently, based on feedback obtained during the retreat,4 meetings were scheduled at various times during the fall semester of 2004 to discuss the peer review process.

The summer faculty retreat was the ideal forum for a relaxed, facilitated discussion and brainstorming on 5 topics:

(1) What is it that you personally want peer review to accomplish?

(2) What do you see as the main objectives of peer review?

(3) Describe the ideal process of peer review.

(4) What are the desired characteristics of feedback from peer review?

(5) What should be reviewed?

One of the authors who is an instructional design faculty member facilitated an initial exercise that encouraged participants to think creatively. Faculty members were then divided into 5 groups and each group assigned one question to discuss. They were given 15 minutes to state answers and transcribe them to a flip chart. After the allotted time, each group's spokesperson presented the group's response. The entire faculty had the opportunity to add further points.

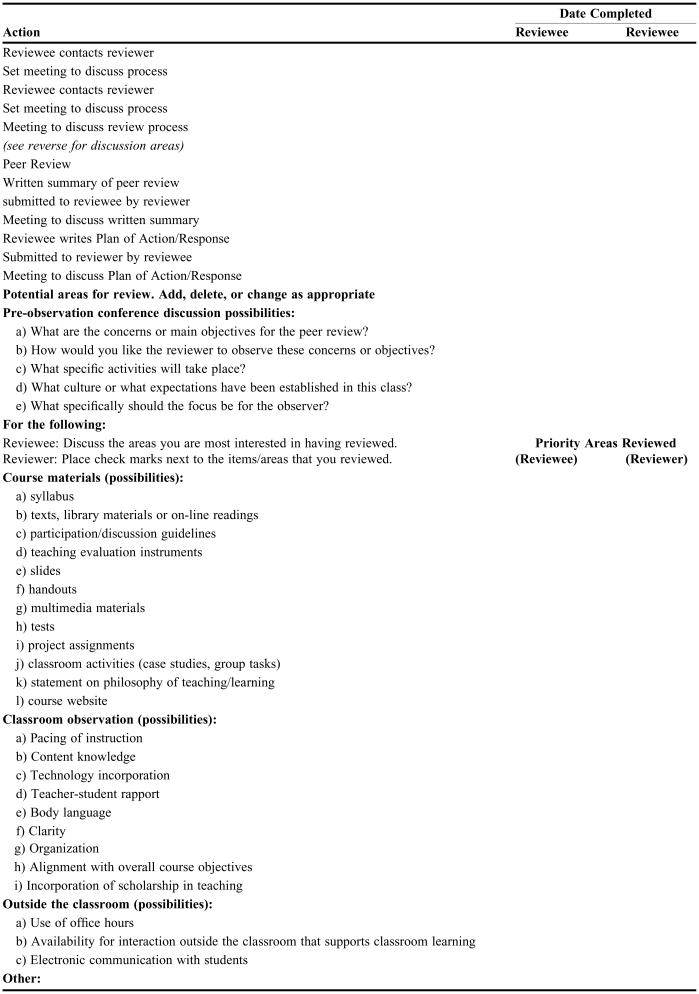

The instructional design faulty member drafted a peer review guide utilizing faculty suggestions and introduced this guide in a series of 4 focus groups for a total of 19 participants who self-selected to participate. Adjustments to the peer review guide were made based on the focus group discussion (Appendix 1). The instructional design faculty member was available for consultation and training for any individual faculty member who desired explanation of the peer review process. Peer review proceeded over the subsequent 2 semesters.

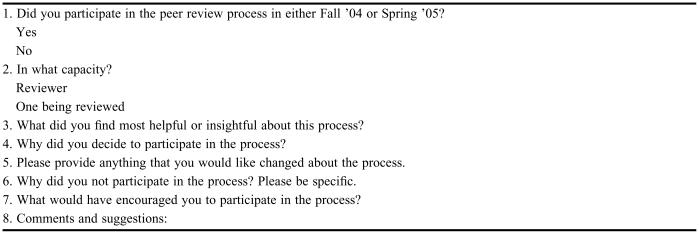

The initial 2 semesters of the peer review process were in place for a total of 30 weeks. At the end of the 2 semesters, all faculty members received a survey instrument via SurveyMonkey to assess participation and satisfaction in the peer-review process as either a reviewer and/or a colleague being reviewed (Appendix 2). The survey instrument included 4 multiple-choice questions and 4 essay questions allowing open-ended answers. The survey instrument was available 24 hours a day for 8 days and 2 reminders were sent. Twenty-six out of 30 faculty members responded.

RESULTS

There was immediate buy-in and acceptance by the faculty in the creation, implementation, and process of peer review. A key factor that bolstered this buy-in was the close involvement of faculty members in the initial discussion, formulation, implementation, and follow-up survey. Faculty members were firm in their desire to keep peer review as a formative process and not a requirement for promotion or portfolio creation. They also preferred not to have results reported to or reviewed by department chairpersons. This preference resulted in a culture of constructive advice and feedback that was non-threatening and unbiased. It reinforced teaching pedagogy as well as exposed faculty members to new techniques and insight on mannerisms and language.

Seven out of 30 possible faculty members participated in the peer-review process over the initial 2 semesters. Six faculty members volunteered to be reviewed, but only 1 of these faculty members agreed to also serve as a reviewer. There were no significant differences in the faculty status of participants and nonparticipants. Two impediments to participation in the process reported by faculty members were perceived lack of time and lack of reminders to participate throughout the semester.

Faculty members' suggestions for improving the process and increasing participation in peer review were:

(1) Periodic reminders about participating in the peer review process;

(2) Lighter teaching and administrative load, thus enabling participation;

(3) Assurance of having enough peer reviewers who were adequately trained and available for the process; and

(4) Request to be asked to be a peer reviewer.

DISCUSSION

To maintain teaching as a scholarly activity and to retain its value, it must have an acceptable way of being improved, critiqued, and judged. As a professional activity, teaching must be monitored and maintained by those who engage in it. Peer review enables those who know the activity best to be a part of critiquing, analyzing, coaching, and evaluating their colleagues. The complexity of teaching does not lend itself to evaluation by unidimensional methods such as solely using student evaluations. Faculty members often mentioned student evaluations as being utilized by students who had an axe to grind, and as being subjective, and at times, not helpful in improving teaching. Thus, faculty members and administrators welcomed the opportunity to institute a formative system of peer review that would add another dimension to teaching review. Faculty members and administrators chose to utilize peer review in a formative manner. However, just as student evaluations could be used in a formative or summative manner, so can peer review.

It was critical that the method utilized for developing the peer review process be embraced by the faculty as opposed to being dictated by the administration. Thus, the summer faculty retreat was the ideal forum for a facilitated discussion and brainstorming on the 5 topics cited above.

Enthusiastic and lively discussion ensued. The focus group process was purposely chosen as a format by the instruction design faculty member for it allowed the faculty to explore the value and purpose of peer review as well as freely self-report apprehensions about peer review. They were able to comment and react immediately to one another's ideas and concerns. In the ensuing discussion, faculty members overwhelmingly wanted to have their teaching validated by a seasoned reviewer who could bring “fresh eyes” to the teaching arena and offer suggestions for new pedagogy. They wanted to have their teaching validated as well as be assured there was student understanding, engagement, and interest. Faculty members wanted to be free of the fear of trying innovative ways of teaching, but also wanted to ensure they were not exhibiting distracting twichings or mannerisms.

Faculty members were emphatic about the process being formative as opposed to summative. In the formative review process, the main emphasis is on providing constructive feedback for improvement to the person being reviewed. On the other hand, summative feedback can serve as the basis for promotion, tenure decisions, pay, or personnel decisions.13

They did not want peer review to be required nor subject to review by the department chairperson. However, they wanted the flexibility to include peer evaluations in a promotion portfolio if they so desired. Faculty members wanted authentic feedback that was clearly linked to improving their teaching and heightening student engagement. They wanted the option of being videotaped but did not want it to be a requirement. Faculty members planned on using the process to improve their teaching and many suggested including the results in their promotion packets when seeking promotion.

There were concerns raised by faculty members that only an expert in adult learning or curricular design could adequately conduct peer review. Despite one of the author's attempts in the focus groups and faculty group discussions to emphasize that all faculty members have the capability and expertise to be reviewers, results of the survey indicated that faculty members were not convinced. Only the author who had the terminal degree in adult learning and curricular design was called upon to do peer review. Thus, a valuable learning opportunity was lost by those who did not serve as reviewers.

None of the faculty members resisted or inhibited the process or its implementation. What was not successful was that three fourths of the faculty members chose not to participate in the process either by reviewing or being reviewed. Although lack of time was the only self-reported reason for not participating, all possible explanations for nonparticipation should be addressed. Although no faculty members overtly stated any of the following reasons for nonparticipation, each should be considered: (1) fear of receiving negative feedback about their teaching; (2) perception of an established right to teach behind closed doors; and (3) feeling uncomfortable with having a knowledgeable colleague in the classroom critiquing them.

Improvements can be made by placing more emphasis on having 100% participation by faculty members in the peer review process. This can be accomplished by issuing periodic reminders, holding frequent workshops on how to be an effective reviewer and how peer review can strengthen teaching, encouraging discussion about the peer review process in faculty meetings, and asking division and department chairs to promote the process. The importance of ensuring that peer review is conducted with honesty and trust and in the spirit of improving teaching cannot be overemphasized.

Faculty members should be encouraged to serve in the role of the reviewer for there is much to be learned by being a reviewer. The reviewer has the opportunity to review good teaching practices, engagement between student and faculty member, learn new content, and become aware of how content is taught in other courses. For more faculty buy-in to take place, further emphasis must be placed on the peer-review program and training on being a peer reviewer must be provided.

Less than a fourth of the faculty took the opportunity and time to be reviewed or to act as a reviewer, which indicates that more emphasis on the importance and value of peer review is needed to improve participation. The buy-in and enthusiasm of faculty members in designing the process was high, but actual level of participation was low due to the previously stated reasons of perceived lack of time and reminders. To overcome this gap, peer review could become mandatory and remain formative.

Those who did participate were enthusiastic about the process. They indicated that they incorporated suggested changes in body language, types of questions posed, teaching pedagogy, timing of questions, lecture formatting, and slide design into their lectures. Faculty members who were reviewed also expressed appreciation for the validation received on the content, syllabus design, engagement with students, discussion pacing, and personal mannerisms. After being reviewed, each faculty member met with the reviewer to discuss the feedback provided. The faculty member also wrote a formal response to the review. This afforded the opportunity for the faculty member to create an action plan for incorporating suggested changes or consciously continuing successful teaching pedagogy.

There are several limitations to this project. As stated above, less than one fourth of our faculty members chose to participate in the process. In addition, this study used a convenience sample at one small southeastern school of pharmacy with a majority of faculty members whose academic rank is assistant professor. Therefore, the obtained results may be different at other schools of pharmacy, particularly those schools with many senior faculty members. Also, while the instrument used in this investigation was developed based on a review of the relevant literature, it has not been validated.

Despite these limitations, this investigation is the first the authors know that describes one method of conducting a faculty peer review process in a school of pharmacy, which may be helpful to others who are interested in incorporating a peer-review process of teaching at their institutions.

CONCLUSION

Investment of time and resources for allowing faculty members to create, participate, and critique their own peer-review process led to a well-accepted program. All who participated stated that the process resulted in increased effectiveness in teaching. It also promoted increased collegiality, acceptance of suggested changes in teaching pedagogy, and validation of good teaching practices. The method utilized to create the peer-review process and instruments was successful in terms of buy-in and having the process in place within 6 weeks of the initial discussion.

What is imperative in this continued process of peer reivew is allowing faculty members time to participate in the peer review process and incorporating pertinent suggested changes and reflecting on the significance of those changes in teaching and learning. Peer review incorporated with student teaching evaluations and each faculty member's reflection upon his/her own teaching produces a multi-dimensional evaluation of teaching.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Terra Walker, Webmaster for the Bernard J. Dunn School of Pharmacy, for her assistance with the survey.

Appendix 1. Guidance for Peer Review: Suggested Sequence of Events and Items for Completion

Appendix 2. Survey Questions for Faculty Members Assessing Participation and Satisfaction in a Faculty Peer Review Process

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnett CW, Matthews HW. Current procedures used to evaluate teaching in schools of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 1998;62:388–91. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chism N. Valuing student differences. In: McKeachie WJ, editor. Teaching Tips. 10th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kidd RS, Latif DA. Student evaluations: Are they valid measures of course effectiveness? Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68 Article 61. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKeachie WJ. Student ratings: The validity of use. Am Psych. 1997;52:1218–25. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aleamoni LM. Typical faculty concerns about student evaluation of teaching. In: Aleamoni LM, editor. Techniques for evaluations and improving instruction. New directions for teaching and learning, no. 31. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arreola RA. Boston, Mass: Anker Publishing Co; 1995. Developing a Comprehensive Faculty Evaluation System: A handbook for college faculty and administrators on designing and operating a comprehensive faculty evaluation system. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmes DS. Effects of grades and disconfirmed grade expectancies on students' evaluations of their instructor. J Educ Psychol. 1972;63:130–3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powell RW. Grades, learning, and student evaluation of instruction. Res High Educ. 1977;7:193–205. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vasta R, Sarmiento RF. Liberal grading improves evaluations but not performance. J Educ Psychol. 1979;71:207–11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Worthington AG, Wong PTP. Effects of earned and assigned grades on student evaluations of an instructor. J Educ Psychol. 1979;71:764–75. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerr S. On the folly of rewarding A while hoping for B. Acad Manage J. 1975;18:769–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seldin P. How colleges evaluate teaching: 1988 vs. 1998. AAHE Bull. 1998;50(7):3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chism N. Peer Review of Teaching: A Sourcebook. Boston, Mass: Anker Publishing Co; 1999. [Google Scholar]