Abstract

Students need strong interpersonal skills to ensure application of their clinical skills and knowledge. Pharmacy schools across the nation must assess the quantity and quality of management skills instruction within their curriculums, including experiential education. The purpose of this article is to describe the importance of the development and utilization of business and people management skills within a community pharmacy, as well as how to incorporate these skills into a student's advanced pharmacy practice experience.

Keywords: community pharmacy, preceptor, management

INTRODUCTION

With the introduction of the first professional doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) degree program nationwide, pharmacy students are receiving more clinical instruction. With the changing dynamics of the pharmacy profession, specifically in community practice settings, students need strong interpersonal and business management skills in addition to their clinical knowledge and skills. Based on the educational outcomes statements of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP), pharmacy schools across the nation must assess the quantity and quality of management skills instruction within their curriculum. This document addresses the management of human and technological resources and emphasizes the importance of managing medication use systems such as quality assurance strategies.1

As with all other aspects of the didactic component of student education, experiential training should support and further develop the skills and knowledge acquired in the classroom. This article discusses areas of pharmacy management in which preceptors can engage students undertaking an advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE). The students can participate in projects that not only help the pharmacy department, but also increase student knowledge and skills in the area of pharmacy management, thereby creating a win-win scenario for the student and the practice site.

The first step toward effectively integrating the didactic component of the curriculum with the experiential component involves identification of the management disciplines to which students should be exposed during their community APPE experience. Those areas of interest include business management, human resource management, and self-management.

BUSINESS MANAGEMENT

In any general discussion of management, business management first comes to mind. With the quality of patient care as the major focus of the educational curriculum within schools of pharmacy, the profitability of the pharmacy service is frequently overlooked. Moreover, the concept of profitability has historically carried a negative connotation in the minds of students. While schools of pharmacy need to address this issue through their curriculum, preceptors can also instruct students during their APPE about the important role profitability plays in the delivery of quality patient care. First, if pharmacists are unable to manage a profitable business, they will not be around to provide care to their patients. Second, the initiation of innovative patient care programs usually involves some start-up costs, which will need to be derived from a profitable pharmacy department.

One aspect of business management about which preceptors should educate students is the function of pharmacy operations. This study begins with education about navigating through an operating statement or a profit and loss statement. Assessment of an operating statement is frequently an overwhelming task for any new pharmacist, much less a pharmacy student. Helping students to achieve a thorough understanding of and ability to use these financial statements will markedly enhance their careers in the business aspects of pharmacy.

The operating statement used at the practice site is an excellent starting point for a preceptor to begin training a student in the fundamentals of business management. Although operating statements come in a variety of shapes and sizes, the essential information about business operations conveyed through them is standard. Although most students have received didactic education on this topic early in their academic careers, their focus normally shifts to the clinical aspects of pharmacy practice without having the opportunity to utilize business operations knowledge for any practical purpose. By encouraging students to use this knowledge during their work on a practice rotation, preceptors reinforce the content of the didactic lectures and supply the student with an invaluable appreciation for this indispensable knowledge.

Beyond these basic financial statements, a pharmacy preceptor should educate students about key financial measures such as sales, gross profit margins (GPMs), and comparison of front store and pharmacy GPM. Students should also receive instruction in the concept of net profit margins (NPM), also referred to as “contribution” or the “bottom line.” Illustrating to a student how a GPM of 19% - 21% effectively translates to a 2% - 4% net profit margin (NPM) can be an eye-opening revelation for students and an important learning tool that demonstrates how strong management skills and training help to maintain an ever-shrinking profit margin.

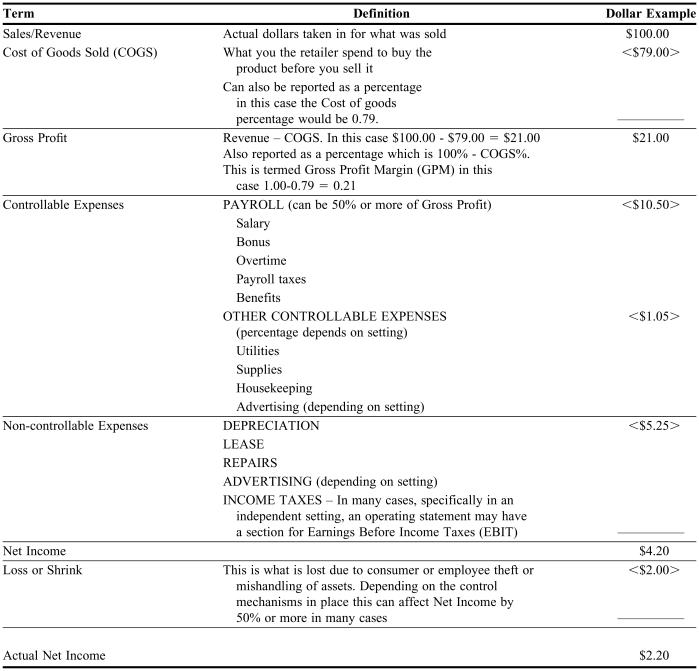

A preceptor who reviews with students the pharmacy expenses that impact net profit margins opens the door to a valuable educational experience about the management and maintenance of profitability. Since preceptors' experiences with APPE students are limited in duration, decisions about the most important aspects of pharmacy operations to cover are critical. Leading students in an organized manner through an operating statement, from sales/revenue to NPM, can be a richly rewarding experience for both pharmacists and students. A chart explaining this process is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Operating Statement Review Chart

In discussions with students about the items that impact profit margins, such as payroll and shrink or loss, preceptors should educate students about the business practices utilized to control these line items as well as the impact that these practices have on pharmacy operations, profitability, and patient care. Once students understand the basic aspects of operating statements, preceptors can encourage students to perform day-to-day, month-to-month, and year-to-year comparisons of other operating statements to identify variances or gaps. (A variance analysis is a comparative assessment of business projections relative to current status.) By using previous year's financial data and comparing it with current year data, students learn how to understand and monitor business trends. This understanding of historical and current business operations provides students with the foundation for comprehending the business goals of the pharmacy enterprise.

As students learn to track business trends, develop a variance analysis, and create a business plan for achieving realistic business goals, both students and preceptors can benefit from the experience. Going further, preceptors can teach students to use variance analysis and reporting to study prescription volume, customer volume, and dollar yield per customer, as well as other statistics that measure the business success of the pharmacy.

Preceptors who work with students should be encouraged to use another key business management teaching tool called a Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT) analysis. Performance of this type of analysis obligates the student to work with other members of the preceptor's team, including pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, and front store managers, to help identify strengths and areas for improvement that might otherwise go unnoticed by the preceptor. Teaching students to evaluate the external environment, such as business competitors moving into or out of the service area, brings the students to a deeper understanding of the important role that a sound business plan plays, as well as the need to be able to revise plans to deal with threats and exploit identified opportunities. By undertaking this process, students may learn to appreciate and identify the reasons for performance variances, which might not have been otherwise considered.

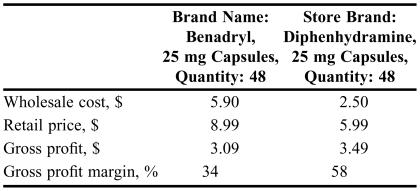

Generic utilization is an interesting and important area worthy of discussion with any novice employee, and especially an APPE student on rotation. Preceptors who help students compare consumer costs (retail prices) with wholesale prices (cost of goods sold) and gross profit of branded versus generic items will provide valuable information about how increased utilization of generic items creates a better value for consumers, as well enhanced profit for the pharmacy business. An actual comparison of a branded versus a store-brand product taken from an average of 5 community pharmacies in the Boston, Mass, area is presented in Table 2. Preceptors need to discuss with their students how increasing generic utilization creates a win-win for the pharmacy and the patient. In providing a more cost effective therapy for a patient, either through generic utilization or therapeutic interchange, pharmacists can in fact improve patient compliance. Medication costs are one of the largest contributors to patient noncompliance. While preceptors can have students spend time in the nonprescription product section of the store doing a clinical analysis on product utilization in specific disease states, students and preceptors should also perform a cost-benefit analysis in their overall product assessment.

Table 2.

Cost Comparison* Between Branded and Generic Drug

Average of 5 chain retailers in the Boston, Mass, area

In a community pharmacy, driving sales and revenue while minimizing expenses is the most productive way of creating profitability. Other than payroll, inventory control represents one of the most significant areas of business operations that can impact profitability and service. Preceptors can help students learn valuable lessons about this crucial business operation. Students who learn to manage the competing dynamics of too much inventory (affecting profitability) with not enough inventory (affecting patient care) get a clear head start in their profession. Much of the inventory discussion can occur with students during an introductory pharmacy practice experience (IPPE). One example of an inventory control project for students would be to conduct a variance analysis and then prepare a report detailing the pharmacy department's current inventory versus its desired inventory. While many sites have different systems of setting and controlling inventory, the basic concepts of days of supply or inventory turns should be discussed. Without understanding the “why” behind the systems, one can not truly utilize the system to its full potential. Students should be taught why a specific days-of-supply or inventory turn is suggested for the site they are at and how the system can be maximized to ensure a proper balance of minimizing costs while providing a high level of customer service through appropriate in-stock conditions. Specific to APPE students, preceptors might consider creating a program similar to health maintenance organizations (HMOs) with respect to identifying products with poor reimbursement rates and recommending therapeutic alternatives. In this type of project, students could identify opportunities for quality care as well as increased margins and contact prescribers to authorize therapeutic interchanges.

In a chain pharmacy setting, students could learn about wholesaler versus warehouse orders and the resulting differences in cost of goods. Preceptors could then have students evaluate patterns of patient utilization, as well as analyze historical wholesaler orders, to determine how the site could better utilize warehouse orders.

Preceptors should help students learn the importance of first-in-first out inventory control in every practice setting. Important lessons about stock rotation, the impact of outdated stock on shrink leading to decreased net profits, the net profit impact of inventory turns, and decreased days of supply should be part of every student's rotational education. For example, a preceptor might ask a student to identify loss or shrink created over a finite period of time by not rotating stock.

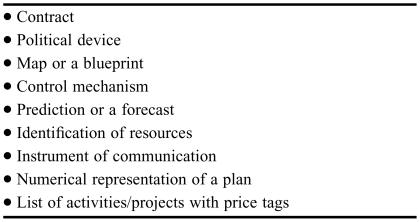

APPE students should learn and understand the roles of budgeting (as shown in Table 3) in the overall operation of the pharmacy department. In today's practice, many chain pharmacies use fixed budgeting systems instead of flexible budgeting systems. Students should understand that fixed budgeting is based on a single level of forecasted demand, while flexible budgeting anticipates variable budget expenses in response to changes in demand.2 Fixed budgeting, specifically formula-based budgeting, is managed and based mostly on templates developed from past performance. Most chain pharmacies use a type of fixed budgeting. In many independently owned and operated pharmacies, the pharmacy manager/owner is able to revise the budget based on market demand. When utilized correctly, flexible budgeting provides a competitive advantage for an independent pharmacy that can allow for quicker inventory and payroll adjustments that provide higher levels of customer service and patient care. Appropriate utilization of a budget is not only crucial for decreasing expenses, it is imperative for ensuring adequate patient care and safety. Hours should not simply be based on the number of prescriptions filled at a site, but rather peak times of processing and filling, patient pick-up and counseling, prescriber calls, and other factors should be taken into consideration.

Table 3.

The Roles of a Budget

Most pharmacy managers in chain pharmacies do not have a direct impact on the day-to-day dollar budget of their pharmacy departments. Instead, chain pharmacy managers administer payroll budgets based on hours utilized versus dollars spent. These preceptors should take the opportunity to illustrate where budgeting is used to plan, coordinate and communicate, monitor progress, and evaluate performance.4

A student project that would illustrate the relationship between labor costs and profitability would be for him/her to compare several months of payroll with net profit statistics to identify the impact that appropriate payroll utilization can have on net profitability. Managers, consciously or unconsciously, budget specific timeslots and tasks for their team and themselves. When labor budgeting is performed in advance, this function is referred to as managing the flow of work, or workflow. In this manner, managers are assessing or analyzing their current processes and learning how to decrease the time needed to fill each prescription. Preceptors should make a conscious effort to identify workflow issues and include APPE students in the process of improving workflow. Students need to understand that improving workflow will not only improve profitability, but also increase the amount of time they have to work with patients. By using specific outcome measures to identify standards of workflow and by involving students in variance analysis of these outcomes, the resulting assessment would not only benefit the students' educational experiences, but also provide useful operational information for the practice site.

Most of the discussion within this article has been grounded in Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) principles, admittedly more from business management aspects and less from quality control and error reduction aspects. Every preceptor should discuss state requirements for CQI with students, as well as the quality control system utilized at the practice site, including past experiences and what mechanisms have been implemented to decrease errors. Students need to develop an appreciation for the different aspects of workflow and how they relate to quality control and quality improvement. Preceptors should refer students to the U.S. Pharmacopeia's web site to evaluate current practices for reporting and preventing medication errors3 and to compare the USP reporting mechanism with the system used at the practice site.

HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

While one of the most important aspects of management, human resource management is usually given the least amount of focus and time in community practices. With the increasing utilization of technology coupled with the growing burden of higher prescription volume, less time is spent developing technicians, pharmacists, and the next generation of pharmacy managers. One of the primary responsibilities of a manager is team development. The first and most important aspect of developing a well-functioning team is to hire employees who not only possess the right skills and credentials, but also exhibit the appropriate attitude, one that meshes with other members of the pharmacy team. This principle applies for pharmacists as well as support personnel.

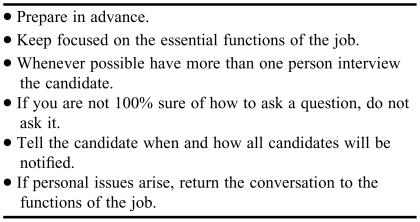

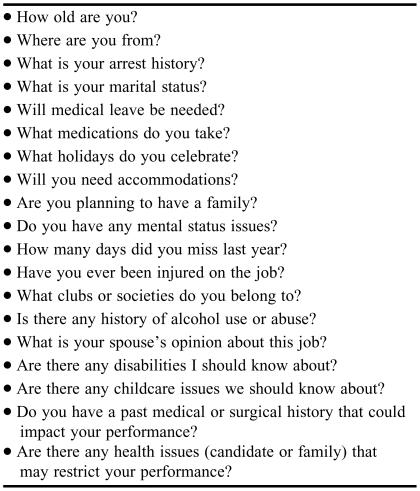

To help APPE students gain an appreciation for the dynamic of human resources, preceptors should involve students, at least as observers, in the interview process. In a chain pharmacy environment, the preceptor could establish a program with the supervising manager to create an interview day for several students. This program would give students early exposure to the interview process. If this process is not viable, preceptors should allow students to review support personnel job descriptions and identify skills and characteristics needed for these positions. Students should be encouraged to use this information to prioritize the necessary skills and characteristics to design high quality, open-ended, or probing interview questions. This exercise serves not only as an educational project for the student, but also an opportunity for the pharmacy manager to enhance the set of interview questions. In this discussion, students should also be exposed to the legal aspects of interviewing. There are several federal and state laws such as the Civil Rights Acts, the Fair Labor Standards Act, the Age Discrimination Employment Act, and the Family and Medical Leave Act that regulate employment practices. Exposing students to potential pitfalls in interviewing would particularly benefit those entering management positions early in their careers. Tips worth sharing with an APPE student have been provided in Tables 4 and 5. While these are not all inclusive lists, these are good talking points for preceptors to use with their students.

Table 4.

Interviewing Pointers

Table 5.

What Not To Ask When Interviewing Prospective Employees/Job Candidates

Given the growing shortage of pharmacists, many chains are moving into centralized hiring of pharmacists and support personnel. This process frees pharmacists to focus on medication dispensing and delivering patient care services. However, managers lose the ability to ensure that individuals who are hired fit into the current team environment. As a result, there is less opportunity to expose APPE students to the interviewing process, and forces preceptors to become more creative in teaching this essential aspect of business management. One way to address this issue would be to establish a regional system of student education in which either the supervising manager or another pharmacist brings all students who are working within a specific geographic area together to expose them to management processes that may not be carried out at individual practice sites. The hiring process would fit well into this type of program.

Another aspect of human resource management to which students should be exposed is the creation of performance appraisals. Formative and summative feedback to team members is essential to building effective teams. Most managers provide formative feedback on a regular basis through weekly and even daily verbal comments to employees on their performance. This feedback includes both positive comments and suggestions for improvement. Summative evaluations are usually delivered annually at the time when a manager formally reviews an employee's performance. This process is extremely important in helping to develop an employee's full potential by making him or her aware of major performance issues. Unfortunately, many times, the summative evaluation becomes an afterthought or a task that a manager performs out of necessity rather than from an understanding about the utility of this process. Two things to consider: the annual summative evaluation should never be a surprise to employees, and employees can sense when a manager takes their professional growth seriously. This process also applies to students. When evaluating a student in an APPE, the preceptor should maintain the same evaluative process as he/she would with an employee. At the beginning of a rotation, the preceptor should ask what the student believes his/her strengths and areas for improvement are as well as the student's expectations about the APPE. This information should be documented and reviewed at the midpoint as well as at the final evaluation. At the beginning of the rotation the preceptor should explain that the student will be treated and evaluated as a member of the pharmacy team. Accordingly, the preceptor should provide formative evaluation throughout the rotation. The student is responsible for reflecting upon this feedback. A midpoint evaluation should be used to keep the student on track and identify areas that need to be covered prior to the completion of the rotation. The final evaluation can be used as an employee performance appraisal. The student should provide a self-evaluation prior to the end of the rotation. Upon review of the self-evaluation, including the catalogue of strengths, areas for improvement, and achievement of rotation objectives that were created at the beginning of the rotation, the preceptor can develop an appraisal which provides the student with specific feedback. This feedback should include suggestions about performance improvement objectives, as well as how to capitalize upon professional strengths. In this manner, the student will begin to understand the applicability of his/her own performance appraisal with the process used to conduct formal employee performance reviews.

Another human resource issue with which managers must deal is poor employee performance. Student performance can be measured in the same manner as employee performance. If the evaluative process is detailed to a student at the beginning of a rotation, the discipline process should also be fully explained. An example of the application of disciplinary procedure would be how a preceptor deals with student tardiness. At the beginning of the rotation, a preceptor should provide a summary of expectations, including dress code, patient confidentiality, and work hours. Many schools provide a learning contract for the preceptor to have the student sign, indicating he/she agrees to adhere to its terms. When and if a student violates one or more of the expectations, the preceptor may carry out various disciplinary procedures. The preceptor should use these procedures as a means to not only improve performance but teach the student the value of discipline, including the consequences of continued poor performance.

SELF-MANAGEMENT

The final aspect of management covered in this article is self-management. Time management and organizational skills are major components of self-management. While organizational skills, for example, may be an area in which students can improve, some students may never overcome this weakness. The preceptor's role in the development of student self-management skills is to help students identify strengths and areas/opportunities for improvement. In most cases, confirming students' beliefs about their strengths, and helping them identify weaknesses and areas for improvement are all that can be accomplished in a single APPE rotation. A preceptor can encourage students to continually perform self-reflection. Based on experiences on a number of rotations and feedback from preceptors, over time, students can begin to build their personal profiles. The specific rotation in which a student is working will affect the input a preceptor can provide relative to student strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities for improvement. With the help of a mentor, either at their place of employment or within the pharmacy school, students can use a vast collection of self-management information and feedback to learn how to improve their performance, utilize the strengths of others to overcome weaknesses, and capitalize on their own strengths. A mentor can also support a student based on the information gathered regarding the type of position in which he/she may excel as a pharmacist. Throughout the entire rotation cycle, students can learn how their strengths directly relate to the job requirements for various positions throughout the pharmacy profession. One project a preceptor or mentor can encourage students to perform is to ask people they trust to provide them with a list of what they believe the students' strengths are. Students should then review these lists and create summaries of their strengths.5 These reviews should be shared with mentors. Mentors can help students evaluate what they can do in the future to capitalize on these strengths. Students may begin these tasks early in their APPE rotations, but should not complete them until the conclusion of their final rotations. At that point, the student will have enough information to develop a plan for a successful career in pharmacy.

CONCLUSION

Preceptors within the community setting have a vast knowledge and experience in the area of pharmacy operations. While many schools of pharmacy teach aspects of pharmacy management, student learning increases with hands on application. Preceptors can improve student attitudes about the pharmacy management aspects of practice by introducing them to management situations occurring at the practice site. This will also provide an excellent basic understanding necessary to becoming an effective community pharmacist for those students choosing to enter into a community career.

REFERENCES

- 1. Educational Outcomes 2004. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education. Available at: http://www.aacp.org/Docs/MainNavigation/Resources/6075_CAPE2004.pdf Accessed January 31, 2006.

- 2.Carroll NV. Financial Management for Pharmacist. 2nd ed. Baltimore, Md: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1998. pp. 99–100. [Google Scholar]

- 3. United States Pharmacopeia Medication Error Reporting System. Available at: http://www.usp.org/patientSafety/mer Accessed on January 31, 2006.

- 4.Managers Toolkit, 13 Skills Managers Need to Succeed. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Publishing; 2004. p. 219. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts LM, Spreitzer G, Dutton J, Quinn R, Heaphy E, Barker B. How to play to your strengths. Harvard Bus Rev. 2005 Jan;:2–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]