Abstract

Objectives

To develop and validate an instrument that measures professionalism among pharmacy students and recent graduates.

Methods

A pharmacy professionalism survey instrument developed by a focus group was pretested and then administered to all first-year pharmacy students enrolled in the University of Georgia College of Pharmacy and to recent pharmacy graduates who were taking the preparation course for the Georgia Pharmacy Law Examination and North American Pharmacist Licensure Examination. Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with each of 32 items using a 5-point Likert scale.

Results

One hundred thirty first-year pharmacy students and 101 pharmacy graduates participated in the survey. Statistical analysis identified 6 factors (subscales), which were later named excellence, respect for others, altruism, duty, accountability, and honor/integrity, the 6 tenets of professionalism. Item to total correlations ranged from 0.25 to 0.57 on the 6 factors (subscales), and reliability estimates ranged from 0.72 to 0.85 for the 6 factors and total scale.

Conclusions

The Pharmacy Professionalism Instrument measures the 6 tenets of professionalism and exhibits satisfactory reliability measures. Future studies using this scale in other pharmacy populations are needed.

Keywords: pharmacy students, professionalism, survey development, validation

INTRODUCTION

The fundamental purpose of colleges and schools of pharmacy is to produce pharmacy practitioners who are capable of performing adequate pharmaceutical care and motivated to better serve humanity. Over the last 5 years, several articles have been published questioning the professionalism of pharmacy students, and whether colleges and schools of pharmacy are fostering professional attitudes and behaviors.1,2 In response to this, the American Pharmaceutical Association (APhA) Academy of Students of Pharmacy (ASP) and the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) Committee on Student Professionalism developed a “Pharmacy Professionalism Toolkit for Students and Faculty.”3 This toolkit was developed to be a resource of specific activities and strategies that students and administrators can use to effectively promote and assess professionalism within colleges and schools of pharmacy.

According to the APhA-ASP/AACP Council of Deans Task Force on Professionalism,4 pharmacists and pharmacy students act professionally when they display the following 10 broad traits5:

accountability for his/her actions

commitment to self-improvement of skills and knowledge

conscience and trustworthiness

covenantal relationship with client (patient)

creativity and innovation

ethically sound decision-making

knowledge and skills of a profession

leadership

pride in the profession

service oriented

Academic medicine and the medical profession have been faced with similar challenges associated with professionalism in both their students and graduates. In 2001, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) described the necessary elements of professionalism as commitments to:

the highest standards of excellence in the practice of medicine and in the generation and dissemination of knowledge;

sustain the interest and welfare of patients;

be responsive to the health needs of society.6

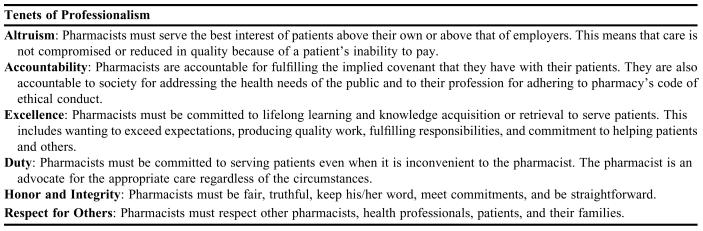

ABIM indicated, with the support of many individuals in academic pharmacy, that to fulfill the above 3 elements, individuals must possess the characteristics of the 6 tenets of professionalism.1 These 6 tenets include altruism, accountability, excellence, duty, honor and integrity, and respect for others, and Table 1 describes these 6 tenets as they were adapted by Hammer et al and Chisholm et al.1,6 Hammer and colleagues used these 6 tenets defined by the ABIM and adapted them specifically for pharmacists (Table 1).1,6 In most cases, these 6 tenets have distinct characteristics; however, at times they may involve overlapping characteristics. Nonetheless, all 6 are important professionalism traits.

Table 1.

Six Tenets for Professionalism in Pharmacy

Adapted by Hammer and Chisholm from Tenets of Professionalism established by the American Board of Internal Medicine.6

There is a need for valid and reliable assessment tools that evaluate professional behaviors.3 In 2000, Hammer and colleagues published a study involving the development and testing of an instrument to assess the behavioral aspects of professionalism in pharmacy students during the advanced experiential training portion of their pharmacy training.7 The focus of this study was the evaluation of students’ professionalism based on preceptors’ observations over the course of the experiential training. More than 25 years ago, Schack and Hepler modified Hall's professionalism scale, which measures 5 attitudinal attributes of professionalism:

use of the professional organization as a major referent;

belief in public services;

belief in self-regulation;

sense of calling; and

belief in autonomy.

However, this scale was developed with a sample of pharmacy practitioners rather than students.8 Over 6 years ago, Lerkiatbundit, building on Schack and Hepler's work, further modified Hall's scale and measured professionalism in pharmacy students at Prince of Songkla University, Thailand.9 The purpose of Lerkiatbundit's study was to assess students’ changes in professionalism over time. A questionnaire was administered to students in all years of the curriculum at the beginning and end of the school year. Results of the survey indicated an increase in most students’ beliefs in professional organizations and public service among every class except for freshmen.

There are no published studies describing the development and validation of a self-assessment instrument designed to measure professionalism among pharmacy students and recent pharmacy graduates. An instrument that can measure student professionalism throughout the pharmacy curricula is needed.7 The objectives of this study were to develop and introduce such an instrument.

METHODS

In 2003, investigators formed a focus group to discuss professionalism in pharmacy with the goal of developing items for a survey instrument that would measure pharmacy students’ professionalism. The focus group consisted of pharmacy students, pharmacists, and pharmacy faculty members. Each of these cohorts met separately to minimize fears of speaking freely and voicing opinions. To limit the number of items generated for the survey instrument and to provide developmental direction, ABIM's 6 tenets were used. All repeat items were eliminated and a preliminary pool of 51 items that were believed to describe the 6 tenets of professionalism was generated.

The survey instrument was pretested by 25 pharmacy students at the University of Georgia and 25 pharmacy residents or newly employed pharmacists (within 5 years of employment) from the Medical College of Georgia and Memorial Health University Medical Center. Based on feedback from the students, residents, and pharmacists, 19 items were deleted because of uncertain meaning or similarity to/duplication of other items in the instrument.

To develop an instrument that can be used to measure professionalism in new pharmacy students as well as recent pharmacy graduates (graduated within 1 month), 2 different populations were utilized: first-year pharmacy students and recent pharmacy graduates. In spring 2004, the 32-item survey instrument was administered to all first-year pharmacy students enrolled in the Clinical Applications course at the University of Georgia College of Pharmacy (n = 133). In spring 2004, the same survey instrument was administered to recent pharmacy graduates who were taking the preparatory review course for the Georgia Pharmacy Boards. Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with each of the 32 items using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Participation in the study was voluntary and the identity of the participants was blinded to the investigators. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Georgia.

All data were entered in Microsoft Excel and later downloaded into SAS. Descriptive statistics were calculated and all data were evaluated to determine whether each item had sufficient variance to proceed with further analyses. Scores of negatively worded items were reversed, so that higher scores reflected more positive attitudes. Scale dimensionality, which is the number of separate constructs assessed by scale items, was assessed using exploratory factor analysis.

Exploratory factor analysis was applied to the data to determine the number and nature of the underlying factors responsible for the covariation in the data. A scree test and a parallel analysis criterion were used to determine the number of meaningful factors. The latter compares a randomly produced set of eigenvalues (based on the sample size as the observed data) with those produced by the observed data. The observed and randomly produced eigenvalues were then plotted against the number of variables. The number of extractable factors was given by the value immediately prior to the crossing point of the plots.10 Items were considered to have loaded on a factor if the factor loading was at least 0.50 on that factor and less than 0.40 on any other factor. Scale reliability (the extent to which scale scores reflect systematic and not random variance) was estimated using Cronbach's alpha coefficient of internal consistency, which indexes homogeneity of scale items, for each factor and for the entire scale.11–15 Chi-square tests with Bonferroni adjustments were used to detect whether there were gender differences or class differences (first-year pharmacy students vs. recent pharmacy graduates) between item scores. Male and female participants and first-year students and recent graduates were compared on every item (18 items), each subscale (6 subscales), and the total scale. Twenty-five tests (18 items + 6 subscales + 1 total scale) for the gender variable and 25 tests for the pharmacy class variable were conducted, yielding a total of 50 tests; thus, the Bonferroni's adjustment was applied to keep the overall alpha for the 50 comparison tests at 0.05 (p < 0.05 divided by 50 is equivalent to p < 0.001).

RESULTS

One hundred thirty (130) first-year students completed and returned the survey instrument resulting in a response rate of 97.7%. One hundred one recent pharmacy graduates completed and returned the survey instrument for an 80.8% response rate. Seventy-five (33%) of the participants were male and 156 (67%) were female. The mean age of the participants was 25.4 years ± 4.88.

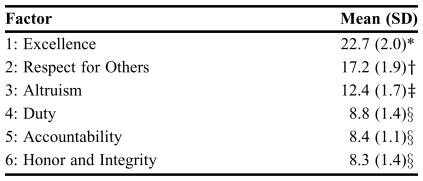

After examining the results of the descriptive statistics of the 32-item survey instrument, 8 items were deleted from further analyses due to severe range restriction (all responses were 1 = strongly disagree or 5 = strongly agree), as it was determined that these items lacked discrimination and were unjustifiable to keep as part of the instrument (leaving 24 items for analysis). Four additional items were deleted from the scale because greater than 20% of the respondents indicated that they did not understand the item (leaving 20 items for analysis). One item was deleted because it loaded on 2 or more factors (leaving 19 for analysis), and another item was deleted because it failed to have a significant loading of 0.50 on any factor (leaving 18 items for analysis). With these items deleted, the principal factor method was used to extract the factors. After the number of constructs was identified for the remaining 18-items, the factors were rotated using the Oblique method. The scree test in combination with the parallel analysis criterion suggested that 6 factors existed. After reviewing the items and the 6 factors, the 6 factors (subscales) were later named excellence, respect for others, altruism, duty, accountability, and honor/integrity as they reflected qualities of the appropriate tenets in Table 1. The variance for excellence was 18%; respect for others, 17%; altruism, 14%; duty, 8%; accountability, 9%; and honor/integrity, 9%. The 18-item instrument was given the name Pharmacy Professionalism Instrument (PPI). See Table 2 for the mean scores and standard deviation of each of the factors. See Table 3 for the response frequency and mean score and standard deviation of each of the 18 items. The mean score of the entire 18-item scale was 77.8 ± 5.9, with a lowest to highest achievable score of 18 to 90. Item to total correlations ranged from 0.25 to 0.57 on the 6 factors. Reliability estimates were as follows: 0.75 for excellence, 0.72 for respect for others, 0.83 for altruism, 0.77 for duty, 0.83 for accountability, and 0.85 for honesty/integrity.

Table 2.

Mean Scores for Factors

*Lowest to highest achievable score is 5 to 25

†Lowest to highest achievable score is 4 to 20

‡Lowest to highest achievable score is 3 to 15

§Lowest to highest achievable score is 2 to 10

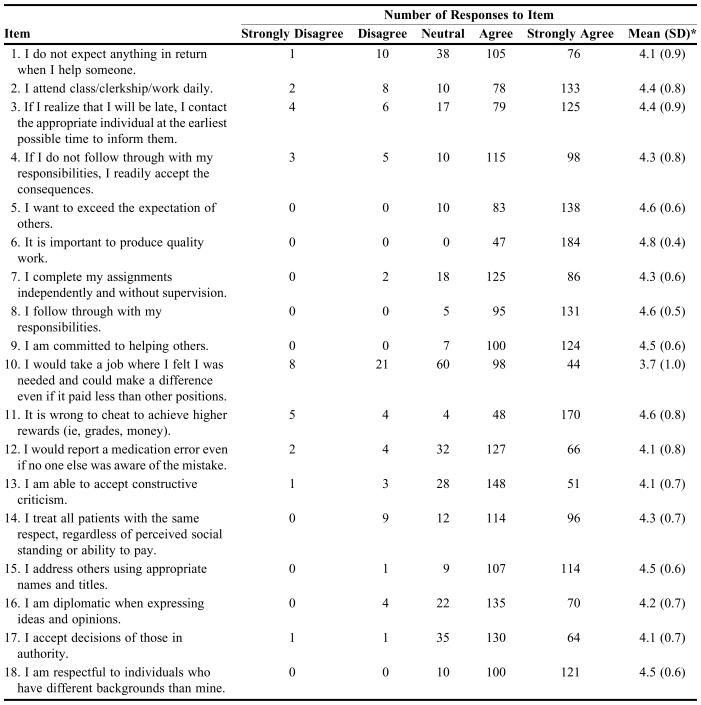

Table 3.

Frequencies of Students’ Responses to Items on the Pharmacy Professionalism Instrument (N = 231)

*1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = neutral; 4 = agree; 5 = strongly agree

The alpha coefficient for the entire 18-item scale was 0.82. There were no gender or class differences (first-year pharmacy students vs. recent pharmacy graduates) between the 6 subscales (factors) and total scale (p > 0.05). On only 1 item, “I would take a job where I felt I was needed and could make a difference even if it paid less than other positions,” was a significant difference found between men's and women's scores, with women indicating greater agreement than men (3.82 ± 0.95 vs. 3.28 ± 1.02; p < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Valid and reliable instruments are necessary to measure professionalism. This study represents the first step in developing a tool that students can use to measure their own professionalism and yielded an 18-item scale consisting of 6 subscales that describe the 6 tenets of professionalism.

We spent a great amount of effort and time on the item development stage of this project. We started with a global approach with the generation of our items, and initially had greater than 50 items (which consisted of approximately 8 items that we believed represented each of the 6 tenets of professionalism). Twenty-five pharmacy students and 25 pharmacy residents or newly employed pharmacists (within 5 years of employment) helped us to reduce these items to 32. Also, further reduction in the items occurred when items were deemed to be confusing to respondents, loaded on more than one factor, did not load on any factor, or had restricted variance. Ultimately, an 18-item instrument was developed that produced 6 factors. As anticipated, these 6 factors appropriately represented each of the 6 tenets of professionalism, which are altruism, accountability, excellence, duty, honor and integrity, and respect for others.

Although it is desired to test the instrument's nomologic validity (nomological validity defined as the extent to which scale scores relate to other variables as would be predicted theoretically) we realize that nomologic validity testing in this case would be challenging and should be done as the next step after exploratory factor analysis given the results of this study. An example of a testing of nomologic validity would be using allograft rejection as a measure of renal transplant patients’ immunosuppressant therapy non-adherence, since evidence demonstrates that non-adherence to immunosuppressants increases allograft rejection.16,17 In order to test the nomologic validity of the PPI, outcome measures of professionalism must be determined. In other words, “What are the outcome measure(s) that should be used to test the nomologic validity of professionalism?” Is one student considered less professional than another because he/she is only a member of one student organization rather than multiple professional organizations? Or perhaps, is one more professional than another because he/she works at a pharmacy rather than in another setting or not at all? Is one pharmacist more professional than another based on the type of service he or she provides? Are not all services provided by pharmacists important? Is it fair to base the extent of professionalism on an individual's salary or the amount of time volunteered for services? The answers to these questions are, at the very least, subjective. Nonetheless, one of the next steps in validating the PPI is to establish reasonable measures of nomologic validity. Future testing comparing the PPI's measure of professionalism to other professionalism constructs may also provide details of nomologic validity. Additionally, future studies focusing on determining how well the instrument's scores discriminate between those who are considered professional and those who may have more difficulty with exhibiting professional behavior should be conducted.

Based on the results of a prior study by the investigators, we were not surprised to find no difference in professionalism between first-year students and recent graduates. A study conducted by Duke et al found that first-year students believed more strongly than third-year students (p = 0.003) that their peers’ actions conveyed the importance of professionalism.18 In the study, there were no differences found among first-year, second-year, and fourth-year students concerning beliefs of whether fellow pharmacy students’ actions conveyed the importance of professionalism.18 Lack of difference between the 2 groups in our study (first-year students vs. recent graduates) may be due to: (1) the high scores on the PPI for first-year students, thus producing a ceiling effect; and (2) a possible decrease in the pharmacy students’ professionalism after the first year in pharmacy school and a rebound in professionalism occurring during the fourth year of pharmacy school (representative of recent graduates), as this phenomenon was seen in the study conducted by Duke and colleagues.18

This study represents the first step of many needed steps to develop an instrument that pharmacy students can complete to measure their professionalism. Limitations and shortcomings exist with the PPI, and future work should focus on addressing these limitations. One of the major concerns of the PPI is that 3 of 6 factors (factors 4, 5, and 6) only have 2 items. Interpretation of factors defined by only 1 or 2 variables can be problematic19; therefore, future studies should focus on the addition of items to factors 4, 5, and 6. It is also important to note, that results from this study may only be applicable to the study population. An important research problem is to determine the similarities of construct factors in different populations and analyses20; therefore, studies using this instrument in other populations are currently ongoing and testing to determine whether the factor structure of the professionalism measure is the same among different groups will be conducted.

CONCLUSIONS

An 18-item instrument, called the Pharmacy Professionalism Instrument was developed, which measures the 6 tenets of professionalism (altruism, accountability, excellence, duty, honor and integrity, and respect for others) and exhibits satisfactory reliability measures. Future studies using the Pharmacy Professionalism Instrument are needed to enhance this scale. Results generated from this study may only be applicable to the study population; therefore, studies using this scale in other pharmacy populations are encouraged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hammer DP, Berger BA, Beardsley RS, Easton MR. Student professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67 Article 96. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chisholm MA. Diversity: a missing link to professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68 Article 120. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pharmacy Professionalism Toolkit for Students and Faculty (version 1.0, 2004), American Pharmaceutical Association Academy of Students of Pharmacy and American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Committee on Student Professionalism. Available at: http://www.aacp.org/Docs/MainNavigation/ForDeans/6428_PharmacyProfessionalismToolkitv.1.pdf Accessed January 4, 2005.

- 4. American Pharmaceutical Association Academy of Students of Pharmacy and American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Council of Deans Task Force on Professionalism. White Paper on Pharmacy Student Professionalism. Available at: http://www.aphanet.org/students/leadership/professionalism/whitepaper.pdf Accessed January 4, 2005.

- 5.Ten Marks of Professional Working Smart. 5. Vol. 17. New York: National Institute of Business Management; 1991. Mar 11, [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Board of Internal Medicine Committees on Evaluation of Clinical Competence and Clinical Competence and Communication Programs. Project Professionalism. Philadelphia, Penn: American Board of Internal Medicine; 2001. pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammer DP, Mason HL, Chalmers RK, Popovich NG, Rupp MT. Development and testing of an instrument to assess behavioral professionalism of pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64:141–51. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schack DW, Hepler CD. Modification of Hall's professionalism scale for use with pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 1979;43:98–104. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lerkiatbundit S. Professionalism in Thai pharmacy students. J Soc Admin Pharm. 2000;17:51–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horn J. A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1965;30:179–85. doi: 10.1007/BF02289447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Churchill GA. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J Market Res. 1979;16:64–73. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghiselli EE, Campbell JP, Zedeck S. Measurement Theory for the Behavioral Sciences. San Francisco: Freeman; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinkin TR. A review of scale development practices in the study of organizations. J Manage. 1995;21:967–88. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinkin TR. A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Organ Res Methods. 1998;1:104–21. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chisholm MA, Lance CE, Williamson GM, Mulloy LL. Development and validation of the immunosuppressant therapy adherence instrument (ITAS) Patient Educ Counseling. 2005;59:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chisholm MA, Lance CE, Williamson GM, Mulloy LL. Development and validation of an immunosuppressant therapy adherence barrier instrument. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;20:181–8. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duke LJ, Kennedy WK, McDuffie C, Miller M, Sheffield M, Chisholm M. Student attitudes, values, and beliefs regarding professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69 Article 104. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 4th ed. Boston, Mass: Allyn & Bacon; 2001:; 2001. p. 622. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nunnally JC, Bernstein I. Psychometric Theory. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, Inc; 1994. p. 548. [Google Scholar]