Abstract

Objective

To provide interdisciplinary structured activities in academic and clinical settings for introducing the concept of professionalism to health professions students.

Design

Undergraduate and graduate students from 8 health care disciplines including pharmacy, nursing, communication sciences and disorders, dietetics and nutrition science, genetic counseling, advanced medical imaging, medical technology, and physical therapy participated in an orientation program focusing on interdisciplinary health care and professionalism, as well as a field experience.

Assessment

Survey results from both components (orientation, n = 284; field experience, n = 123) indicated that the project was valuable in increasing students’ awareness of (1) the importance of professionalism in the clinical setting and (2) the potential contributions of their profession to the health care team.

Conclusion

Health professions curricula should include interdisciplinary learning opportunities that enhance collaboration, collegiality, and professionalism among future members of the health care team.

Keywords: professionalism, interdisciplinary, interprofessional, health professions

INTRODUCTION

The concept of professionalism is multifaceted and may be divided into 3 categories: professional parameters, professional behaviors, and professional responsibilities.1 Professional parameters include legal and ethical issues; professional behaviors refer to discipline-related knowledge and skills, appropriate relationships with clients and colleagues, and acceptable appearance and attitudes; professional responsibilities include responsibility to the profession and to oneself, clients, employers, and community. Thus, students must develop a wide range of characteristics, attitudes, and behaviors as well as a lifelong commitment to professionalism.2

Educators have an obligation to promote and evaluate students’ professional development as well as their knowledge and clinical skills, and to do so in spite of potential barriers such as overcrowded curricula, scheduling difficulties, and faculty attitudes.3–5 Professionalism can be informally taught through modeling by instructors and preceptors; however, a more structured approach can enhance students’ abilities to identify and assimilate the values and behaviors associated with professionalism.5 Although curricula often address some aspects of professionalism (eg, legal and ethical issues), there is little information in the literature about how to effectively teach the entire scope of professionalism.

According to the Institute of Medicine report, “Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality,” all health professionals should be educated to coordinate, collaborate, and communicate with one another in interdisciplinary teams to make clinical decisions and solve ethical dilemmas.6,7 By integrating discipline-specific knowledge, skills, and perspectives, team members can provide optimal patient care that encompasses the expertise of each health professional. Students should be provided with interdisciplinary learning opportunities throughout the curricula to enhance understanding and appreciation for their profession's potential contributions to the health care team, as well as the contributions of other disciplines.

The purpose of this project was to provide interdisciplinary learning opportunities that would promote the development of professionalism in health professions students. The overall objectives of the project were to: (1) define the importance of professionalism in clinical experiences, (2) increase awareness of the roles of other health professionals in interdisciplinary settings, and (3) increase collaboration among students and faculty members from various health-related disciplines. The project included experiences in both academic and clinical settings to optimize the students’ understanding of their own and other professionals’ roles on the health care team.

DESIGN

Faculty members from the Colleges of Pharmacy, Nursing, and Allied Health Sciences at the University of Cincinnati formed an Interdisciplinary Task Force to plan and implement an interdisciplinary project to introduce health professions students to the concept of professionalism. This University-funded project included 2 main components: an interdisciplinary orientation and a field experience.

Orientation

The Interdisciplinary Task Force (ITF) planned a half-day orientation entitled “Professionalism: An Interdisciplinary Approach” for students from their respective colleges. The orientation was offered immediately prior to the start of the academic year. The goals of the orientation were to introduce students to the importance of professionalism in clinical sites, to provide information about the participating health disciplines, and to provide opportunities for interaction among students from several health disciplines. A combination of lecture and active-learning activities were used to address these goals.

Upon arriving at the orientation, students were given an information packet that included a name badge coded according to the student's profession, background information about the project, and a list of references on professionalism. The orientation began with a welcome by the ITF, an explanation of the project, and an introduction to professionalism.

The elements of professional behavior were demonstrated through the use of role-play performed by student volunteers. Students enacted clinic-based scenarios displaying nonprofessional behaviors, skills, and attitudes, followed by an audience discussion of professionalism. The scenarios then were reenacted displaying professional behaviors.

To illustrate the multifaceted nature of professionalism, students were assigned to interdisciplinary groups to define elements of professionalism. Each group was given the task of listing multiple characteristics of professionalism and choosing the 5 most important characteristics. Groups then reported their results, which were tabulated onsite. The 10 most reported characteristics were used on the field experience survey described later. An ITF member led a discussion about the commonalities of the reported traits and behaviors among the student groups.

As a final active-learning experience, students had an opportunity to collaborate and use their problem-solving skills on a case study that involved an ethical dilemma in health care. The same small groups were given information about an elderly patient in the terminal stage of gastrointestinal cancer and a dilemma regarding discontinuation of tube feeding. Each group answered case-related questions and reported their findings to the audience; a discussion among faculty members and students followed.

At the conclusion of the orientation, students were given time to visit booths that displayed the curricula and activities of the 3 participating colleges with representatives from each college available to answer students’ questions.

Field Experience

The second component of the project for those students who attended the orientation was an educational experience in which they were placed in an interdisciplinary clinical/community site with a clinician from a discipline other than their chosen field of study. The objectives of the field experience were for students to gain insight into the roles and responsibilities of another health professional, observe professional traits and behaviors present at the site, and consider how their own discipline might contribute to the site.

Students contacted the study coordinator who then placed them with health care practitioners. Most placement sites were located in inpatient and outpatient departments of local hospitals. Diverse experiences were also available at community sites such as a retail pharmacy, drug and poison information center, and child education center. Students, clinicians, and the study coordinator used email, mail, and/or telephone to communicate necessary information. After final placement, a confirmation letter with directions to the site and the evaluation survey were mailed to the students. Students spent 2 hours observing clinical activities and interacting with the professional in the worksite.

ASSESSMENT

Students who had begun their academic program but not their clinical experience were sent letters during the summer by their respective colleges inviting them to participate in the project. Participating programs included: pharmacy, nursing, communication sciences and disorders, dietetics and nutrition science, genetic counseling, advanced medical imaging, medical technology, and physical therapy. Of the 342 students who participated in the project, 284 (83%) completed the orientation survey instrument. Respondents were comprised of 110 students from the College of Pharmacy, 48 students from the College of Nursing, and 126 students from the College of Allied Health Sciences. Ten percent of the respondents were male and 90% were female. The majority of respondents were white, non-Hispanic (92%), with the remainder being Asian/Pacific Islander (5%), black, non-Hispanic (2%), and Hispanic (1%). Although just entering the clinical component of their programs, most students had either volunteered (27%) or were employed currently or previously (59%) in health care settings. However, the majority of students reported either no experience (41%) or less than 1 year experience (37%) working with an interdisciplinary health care team.

Orientation

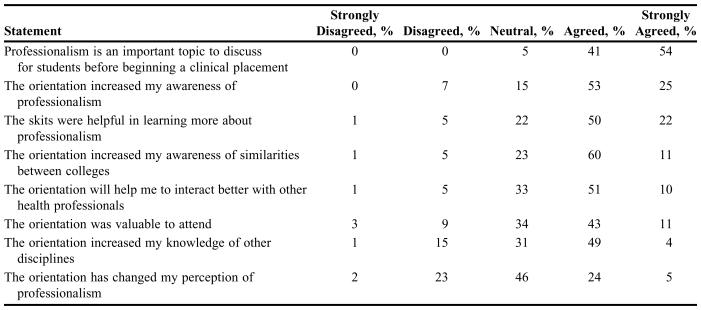

The orientation survey included 8 statements about the orientation and professionalism. Responses were based on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Student responses to the objective statements on the survey instrument are presented in Table 1. According to survey responses, professionalism is indeed an important topic to discuss with students before entering the clinical component of their academic programs. The majority of students felt the orientation increased their awareness of professionalism, knowledge of other health disciplines, and awareness of the similarities among the 3 participating Colleges. Most students also agreed the orientation would enhance their future interactions with other health disciplines.

Table 1.

Responses (%) of Health Professions Students to Statements Regarding an Orientation Seminar on Professionalism (N = 284)*

At least a 99% response rate was obtained for each survey question

Three open-ended statements addressed: (1) other topics of interest to the student, (2) what the student liked best about the orientation, and (3) how the orientation might be improved. Student responses indicated they would like more specific information about the curricula and job opportunities of each discipline and the roles and responsibilities of each professional on the health care team. They particularly liked meeting and interacting with students from other health-related programs in small groups. Suggestions for improvement included increasing the number of interactive group activities, decreasing lecture time, and including medical students in the program.

Field Experience

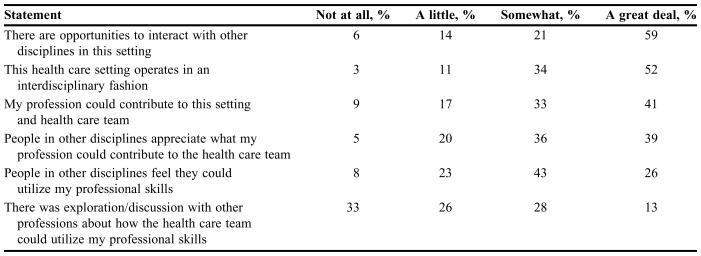

A total of 163 students were placed with clinicians who volunteered to serve as preceptors. One hundred twenty-three students (75%) completed an evaluation survey instrument that included 6 objective statements with responses designed to assess the interdisciplinary nature of the site using a 4-point Likert scale (Table 2).

Table 2.

Responses (%) of Health Professions Students to Statements Regarding a Field Experience in Professionalism (N = 123)*

At least a 99% response rate was obtained for each survey question

Five statements with 4-point Likert scale responses (1 = not at all; 4 = a great deal) were also included to assess the students’ opinion of the field experience. The majority of students felt they benefited from the placement; the experience made them more aware of the potential opportunities available for their profession; and the presence of their profession would improve patient care in the setting.

Additional questions were included for students (1) to indicate whether specific factors were potential barriers that might prevent them from applying their professional role in the site, (2) to indicate how the student's profession might contribute to the site, and (3) to rate the extent to which specific characteristics of professionalism were valued in the site.

Factors identified most often as potential barriers were: time constraints and lack of training of other disciplines to utilize their skills. Students indicated that their profession could contribute to the placement site in the following ways (ranked from highest to lowest number of responses): patient counseling and support; patient education; discipline-specific knowledge to professionals and patients, diagnostic assessment, patient referral, and psychosocial assessment. The majority of students (≥91%) felt the professional traits and behaviors they had identified in the orientation session were valued in their placement setting (ie, respect for patients and coworkers, knowledge of discipline, accountability, flexibility, trustworthiness, ethical behavior, teamwork, confidentiality, honesty, and reliability).

An evaluation survey instrument was mailed to participating preceptors at the end of the project. Preceptors included 37 professionals from the fields of pharmacy, nursing, and allied health (ie, dietetics, genetic counseling, clinical laboratory services, medical imaging, physical therapy, and speech pathology). The survey instrument included 3 questions with responses rated using a 4-point Likert-scale (1 = not at all; 4 = a great deal) and 1 open-ended question to assess the preceptors’ opinion of the field experience. Twenty survey instruments (54%) were returned by the preceptors. The majority of respondents felt the experience was valuable to both the student and the preceptor (ie, in learning more about the student's discipline). Ninety-five percent of the preceptors felt there was potential for more collaboration with other disciplines at their site as a result of the experience.

DISCUSSION

Educational experiences that bring students and practitioners of various health disciplines together can be effective in improving participants’ understanding of professionalism and the health care team. Participation in this interdisciplinary project increased the students’ awareness and appreciation of professionalism in the clinical setting, as well as their understanding of the contributions of their own profession and other health disciplines to the health care team. Ultimately, students felt their participation in the project and their collaboration with other disciplines increased their familiarity with the roles and responsibilities of the health care team. Volunteer preceptors also felt participation in the project increased their understanding of other professions and enhanced their potential for future collaboration with other disciplines.

Although this multi-disciplinary approach to teaching professionalism is valuable, there were limitations of the project. Placement of students in a field experience was the major challenge of the project. Demanding and conflicting schedules of clinicians and students were the greatest hindrances, as well as difficulty in maintaining efficient contact between students and the study coordinator. For these reasons, only 48% of the students who attended the orientation participated in the field experience. Another limitation was the low response rates from students and preceptors to the field experience surveys. To retain anonymity of the respondents, they were asked to mail or deposit the survey instrument in boxes located within their colleges. A better collection method with reminder notices may have improved the response rates.

The differing levels of academic training of the participating students were additional limitations of the project. All students attended the program prior to their clinical experiences; however, graduate students were just entering their academic program, while undergraduate students were beginning the third or fourth year of their academic program. The level of discipline-specific knowledge likely differed depending on a student's length of time at his/her specific College. If students participated in the project after the initial year of their academic program, they may feel more confident and comfortable interacting with peers and preceptors.

A final limitation was the non-inclusion of medical students in the project. As a pilot project, 3 of the 4 Colleges on the University's medical campus were involved in its development and implementation. As suggested by student evaluations, the inclusion of students from the College of Medicine, as well as other health-related academic units (eg, School of Social Work) would enrich the interdisciplinary experience.

Future research should include all of the health disciplines on campus, measurement of changes in attitudes about professionalism (using pre-intervention and post-intervention survey instruments), and participation of preceptors in the orientation. By being involved in the orientation, preceptors would be more familiar with the project and students’ perceptions of professionalism and interdisciplinary health care teams. Following completion of the project, it would be beneficial for students to spend time with professionals from other health disciplines during their clinical rotations, reinforcing the importance of professionalism in interdisciplinary health care.

According to the Pew Health Professions Commission, it is the responsibility of educators to prepare students for the realities of clinical practice, particularly for their participation on interdisciplinary teams.8 Due to the increasing complexity of care, coordination of multiple patient needs, and delivery of care across settings, interdisciplinary teams are essential for positive clinical outcomes.9 Therefore, teamwork among disciplines should be emphasized throughout the curricula of health-related programs to ease students’ transition into interdisciplinary clinical experiences and potentially enhance their effectiveness as members of health care teams. Academic courses and seminars that require socialization and collaboration across disciplines should address professionalism, confidence in discipline-specific knowledge and skills, and respect for the actual and potential contributions of the participating disciplines to optimal health care.10 Small group activities are effective teaching strategies that emphasize the importance of collaboration, collegiality, professionalism, decision making, and problem solving among team members.

In addition to academic coursework, health professions students should be engaged in learning opportunities that allow them to observe health care teams in action and to understand their role as cooperative, rather than competitive, team players. Interdisciplinary clinical experiences allow students to practice and refine their professional and clinical skills in actual health care settings, preparing them for future careers. Interdisciplinary education requires the sincere commitment of faculty members who support and practice professionalism and collaborative team work. To promote cross-disciplinary collaboration, educators must understand their own professional values and beliefs, as well as those of the other group members, and must be open and honest in their communication of their professional knowledge, attitudes, and responsibilities with the group.11

CONCLUSIONS

By participating in an interdisciplinary educational experience, health professions students increased their awareness and understanding of professionalism in clinical settings and the potential contributions of each discipline to the health care team. Faculty members can gain and strengthen students’ commitment to interdisciplinary health care through structured learning activities. Further research is needed to determine the most effective and economically feasible interdisciplinary curricula, but in the meantime, educators can offer a variety of opportunities, such as the orientation and field experience described here, to increase interaction among students, faculty members, and practitioners of various disciplines.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bossers A, Kernaghan J, Hodgins L, Merla L, O'Connor C, Van Kessel M. Defining and developing professionalism. Can J Occup Ther. 1999;66:16–21. doi: 10.1177/000841749906600303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammer DP, Berger BA, Beardsley RS. Student professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibson DD, Coldwell LL, Kiewit SF. Creating a culture of professionalism: an integrated approach. Acad Med. 2000;75:509. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200005000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Randolph DS. Evaluating the professional behaviors of entry-level occupational therapy students. J Allied Health. 2003;32:116–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wear D, Castellani B. The development of professionalism: curriculum matters. Acad Med. 2000;75:602–11. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200006000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cloonan PA, Davis FD, Burnett CB. Interdisciplinary education in clinical ethics: a work in progress. Holist Nurs Pract. 1999;13:12–9. doi: 10.1097/00004650-199901000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pew Health Professions Commission. San Francisco, CA: University of California at San Francisco Center for the Health Professions; 1995. Critical Challenges: Revitalizing the Health Professions for the Twenty-first Century. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Health Professions Education Summit. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brehm BJ, Smith R, Rourke KM. Multiskilling: A course to increase multidisciplinary skills in future dietetics professionals. J Allied Health. 2001;30:239–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glen S. Educating for interprofessional collaboration: teaching about values. Nurs Ethics. 1999;6:202–13. doi: 10.1177/096973309900600303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]