In response to the release of the Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education (CAPE) Educational Outcomes1 revised version in May 2004, the 2004-2005 American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP) Educational Affairs Committee was charged by then-president Barbara G. Wells, PharmD, with reviewing the updated document and recommending strategies for pharmacy educators to apply the information. The recommendations contained in this document focus on guiding curricular development, helping students connect what they learn in the classroom and experiential setting to the practice of pharmacy, educating external audiences about the role of the pharmacist, assessing the new outcomes, and determining the impact on pharmacy education. Recommendations are the result of a review of background information, listed references, and discussion of experiences with implementing the 1998 revised version of the CAPE Educational Outcomes2 (ie, curricular mapping) in new or existing pharmacy programs.

BACKGROUND

In 1992, the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP), under the auspices of CAPE, began an initiative to develop educational outcomes describing the professional knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values that would be expected of graduates of entry-level doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) programs.3 The first Educational Outcomes document appeared in 1994 when approximately one third of pharmacy institutions, including schools, colleges, and universities (hereinafter referred to as “schools”), had implemented the entry-level PharmD degree. The Educational Outcomes were modified in 1998 to address the evolving role of pharmacists. Six years later, in 2004, virtually all schools offered the entry-level PharmD degree.4

During the years since the CAPE Educational Outcomes was first published and revised, significant changes in the health care environment and in the role of pharmacists have occurred. With the increasing complexity and variety of drugs available, technology-enhanced prescription product dispensing, and increased patient access to information resources, the pharmacist is ideally suited for a patient-centered role that incorporates an opportunity to improve patient outcomes through increased patient-pharmacist and pharmacist-health care provider dialogue. The 2004 revision of the CAPE Educational Outcomes1 reflects the dynamic state of pharmacy education.

COMPARING THE 1998 AND 2004 VERSIONS OF THE CAPE EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES

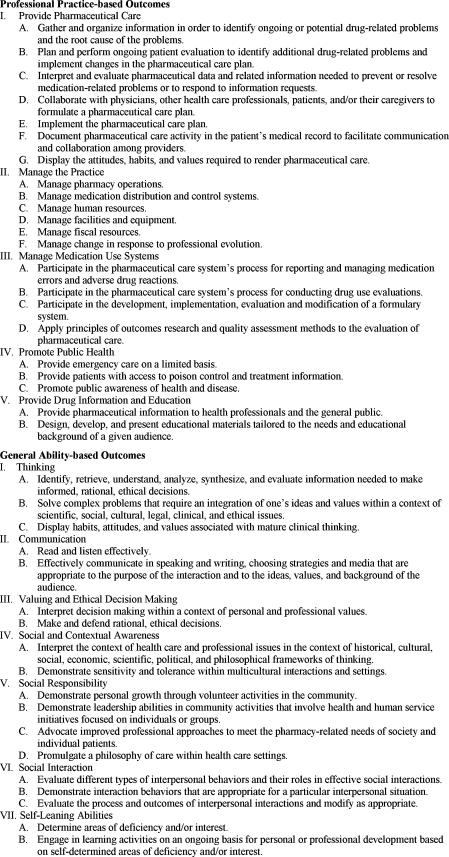

The primary intent of the 1998 document was to provide pharmacy faculty with guidance in designing, assessing, and modifying their school's pharmacy curriculum. By considering position statements regarding evolving pharmacy practice and pharmacy education from various pharmacy organizations (American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, American Pharmacists Association, Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education [ACPE], AACP, and ACCP), the 1998 document provides a descriptive list of 5 professional practice-based outcomes and 7 general ability-based outcomes. The 13-page document provides detailed information and has served as a guide for curricular assessment at many schools. A list of the outcomes can be found in Figure 1. The specific objectives listed under each outcome are omitted from this outline; however, the document in its entirety may be viewed in Portable Document Format.2

Figure 1.

Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education Educational Outcomes, Revised Version 1998.2

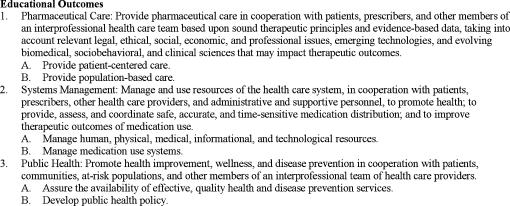

In contrast, the 2004 revision of the CAPE Educational Outcomes is concise, broad-based, and open-ended, allowing broad applicability and long-range utility (Figure 2). The full text can be viewed in Portable Document Format.1

Figure 2.

Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education Educational Outcomes, Revised Version 2004.1

The emphasis of pharmacy practice is shifting to a focus on patient care instead of product provision,5 and this shift is reflected primarily in the pharmaceutical care outcomes area. Although the 2004 CAPE Educational Outcomes continues to assist in curricular development, its intent is to “tell the story to external audiences about the role of the pharmacist” and “to assist students with making a connection between what they are learning and the practice of pharmacy.”1 Also, in an effort to make the document less “prescriptive” and more user-friendly, the educational outcomes were simplified and made less detailed. In contrast to the 12 educational outcomes listed in the 1998 document, the 2004 document lists 3 broad educational outcomes and no longer discriminates between general and discipline-specific abilities. The increased simplicity of the 2004 CAPE Educational Outcomes comes with a price. Collapsing the general ability-based outcomes into the context of the discipline-specific abilities limits the reader's ability to identify the general outcomes crucial to development of discipline-specific outcomes. For example, maintaining professional competence is included in the subsection of Pharmaceutical Care, yet the general abilities necessary to achieve professional competence have been omitted. How does one assess achievement of professional competence when the components describing this outcome are ambiguous?

Since the 1998 document may be viewed as clear-cut but too restrictive because of the level of detail included, the broad scope of the updated document may be viewed as an opportunity to maximize the resources unique to each school. Furthermore, the revised educational outcomes emphasize interdisciplinary patient care, critical thinking, and problem solving while underscoring the need for schools to be forward thinking. The details of topics are left to the individual schools, thereby allowing them opportunities to maximize the strengths and talents of the local faculty and resources while conveying the basic principles of optimal pharmaceutical care.

In general, the lack of detail in the 2004 CAPE Educational Outcomes creates a lapse in direction. The stated outcomes do not address the levels of professional development necessary to achieve the final entry-level outcome. The vagueness allows for wide interpretability of the terminal outcome, and the lack of defined, standardized assessment measures may lead to wide variability in the final product (ie, PharmD graduates). In addition, in attempting to broadly define the knowledge and skills required to be a competent provider, the document neglects to define professional attitudes and values. Many issues facing the profession today encompass the attitudinal component (ie, professionalism, developing future leaders in the profession, ethics, cultural competency, etc). Thus, the CAPE Educational Outcomes fails to fully define the contemporary pharmacist. For the profession to address contemporary issues and to anticipate future ones, specific outcomes incorporating attitudes and values are vital.

UTILIZATION OF THE 2004 EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES

Guiding Curricular Development

The 2004 CAPE Educational Outcomes are intended to be the target toward which the evolving pharmacy curriculum should be aimed.1,2 Many schools have used the 1998 CAPE Educational Outcomes as the template for curricular mapping endeavors. To facilitate these endeavors and to stimulate communication between schools, AACP held annual assessment institutes (from 1998-2003) in exchange for feedback regarding how faculty members were using the document. Hence, many schools adopted the 1998 Educational Outcomes as the definitive set of abilities that each student would conceivably possess upon graduation. Before publication of the 2004 CAPE Educational Outcomes, schools were using the 1998 document to reevaluate their curricula and implement outcome assessment strategies as a means of continuous quality improvement. Even with the adoption of the 2004 CAPE Educational Outcomes, some schools may elect to refer to the more comprehensive 1998 version for more detailed direction in determining student abilities.

Because of the increasing knowledge regarding disease and drug therapy, it is impossible for didactic and experiential pharmacy education to adequately cover all aspects of disease management and pharmaceutical care.6 It is imperative that the pharmacy curricula be dynamic and able to quickly respond to the expected advancement of patient- and population-centered pharmacy practice. The 2004 CAPE Educational Outcomes addresses these expected changes and allows individual schools to maximize their local resources while ensuring that basic principles of pharmaceutical care are learned. However, these outcomes must also be attainable. For example, the outcomes listed in the Systems Management and Public Health sections may be beyond what can be attained in a PharmD program.

In addition to the 1998 and 2004 CAPE documents, several additional pharmacy educational and competency statements either have been published recently or are in the midst of completion. The National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP) recently revised the Competency Statements for the North American Pharmacist Licensure Examination (NAPLEX).7 The 3 competency areas described in the NAPLEX Blueprint correlate with the 2004 CAPE Educational Outcomes:

Area 1: Assure safe and effective pharmacotherapy and optimize therapeutic outcomes

Area 2: Assure safe and accurate preparation and dispensing of medications

Area 3: Provide health care information and promote public health

Within these areas are subheadings that have many similarities to those in the 1998 CAPE Educational Outcomes. Also, newly revised ACPE Standards and Guidelines (available from www.acpe-accredit.org/standards/default.asp) for accreditation of PharmD degree programs will dictate the direction for pharmacy education. It has been recommended that the new ACPE Standards and Guidelines include a clear and uniformly agreed on definition of the term “general practitioner” or “generalist,”8 which is essential in guiding the selection of educational outcomes deemed relevant to the global directive of developing generalist pharmacists.

Recommendation 1

A task force led by the AACP with representatives from ACCP, NABP, ACPE, and other interested stakeholders should be charged with developing Pharmacy Curricular Outcomes National Consensus Guidelines. This may be accomplished through a careful, concerted, concurrent review of the NAPLEX Blueprint, 1998 and 2004 versions of the CAPE Educational Outcomes, and revised ACPE Standards and Guidelines to ensure coordination of the information, with a focus on creating an integrated, cohesive set of standards and identifying attainable and measurable outcomes defining the essential knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values to competently provide pharmaceutical care. The identified outcomes should be descriptive and include examples of information a school can collect to assess achievement of the stated objective. Perhaps a workshop program sponsored by AACP, which includes a small group of faculty from each fully accredited school, will facilitate the interpretation and utilization of the outcomes.

Recommendation 2

The Pharmacy Curricular Outcomes National Consensus Guidelines (see Recommendation 1) and CAPE Educational Outcomes should be disseminated to all faculty in schools of pharmacy by ACPE and AACP to enhance the development, integration, and assessment of educational outcomes at each school and, ultimately, student achievement of the stated outcomes. This may be accomplished through formal faculty training on the development, integration, and assessment of the educational outcomes and creation of an online training program for all faculty to complete. A criterion in the accreditation process could be the attainment of a set percentage of faculty completing the online training modules.

Recommendation 3

Pharmacy schools, more specifically the curriculum committee and perhaps the assessment committee at each institution, should be continually reevaluating the curriculum to ensure the following: first, that the curriculum is targeted toward the current CAPE Educational Outcomes as well as the previously recommended Pharmacy Curricular Outcomes National Consensus Guidelines, if developed (see Recommendation 1); second, that school-specific (ie, content and discipline-specific) outcomes are defined and included in the curriculum; and third, that the process and outcomes measures in development by ACPE are consistent with the Pharmacy Curricular Outcomes National Consensus Guidelines and used as the basis for accreditation of the standards for curriculum.

Recommendation 4

Administrators from all schools must empower faculty to develop, integrate, and assess educational outcomes by providing the necessary resources critical to the implementation and maintenance of this monumental task. Administrators must support faculty endeavors to integrate the outcomes throughout the curriculum first by facilitating faculty and student participation in the process and understanding of the outcomes (ie, sponsoring workshops or retreats focused on curricular mapping, as well as providing adequate support personnel to assist with the project and release time from other responsibilities or reprioritization of college initiatives to adequately accomplish this task); and second, by reinforcing student expectations associated with outcome achievement.

Conveying the Outcomes to Students

Under the tenets of pharmaceutical care,9 it is critical that pharmacy students learn how to translate their didactic and experiential education into a proactive, evolving clinical practice. As students progress through their pharmacy education, they should become familiar with the 2004 CAPE Educational Outcomes and school-specific outcomes. Through their exposure to the 2004 CAPE Educational Outcomes (directly and through the pharmacy curriculum based on the Educational Outcomes), it is expected that students will become proactive members of a comprehensive health care team providing direct patient care, and they will learn that pharmacists cannot isolate themselves from other health care professionals. Furthermore, the 2004 CAPE Educational Outcomes highlights the dynamic nature of pharmacy practice, as well as the need to practice evidence-based medicine and to use the new technologies as they are developed. All of these issues emphasize the need for lifelong learning and continuous self-assessment. It will be up to the individual schools to facilitate the comprehension and engraining of these tenets.

Recommendation 5

Pharmacy schools should introduce students to the educational outcomes (2004 CAPE Educational Outcomes and school-specific outcomes) early and refer to them consistently throughout the pharmacy curriculum to assist the students in assimilation of didactic and experiential education with the demands of their future pharmacy practice. Pharmacy schools must introduce and educate students, on entry into the program, about the assessment tools used at the school, including peer- and self-assessments, so as to engage them in the process of evaluation and achievement of the educational outcomes. Specific examples of 2004 CAPE Educational Outcomes integration may include the following: activities during orientation, inclusion of the outcomes in all course syllabi, clearly articulated links between the outcomes and specific course activities, mentoring-shadowing-internship activities that highlight pharmacist use of specific outcomes, development of a longitudinal curriculum schematic detailing where the outcomes will be addressed, and incorporation of the longitudinal schematic into the academic advising system whereby advisors and advisees review the advisee's progress on an annual or semiannual basis.

Educating External Audiences

The 1998 CAPE Educational Outcomes describes the pharmacy graduate in terms of providing pharmaceutical care, managing practice, managing medication use systems, promoting public health, and providing drug information in addition to having general ability-based skills such as critical thinking, communication, ethical decision making, social and contextual awareness, and social responsibility.2 These terms have meaning to those who practice pharmacy; however, explaining what these terms mean to the general public is difficult.3 It would be easy to appreciate how external viewers (ie, lay press, other health care providers, etc) might get lost in the terminology or simply not have the patience to carefully and thoughtfully review the content. The 2004 CAPE Educational Outcomes represents an integration of the previous work3 in an attempt to streamline, clarify, and simplify the terminology used to describe the educational outcomes of pharmacy programs. The outcome descriptors having been tailored to pharmaceutical care, systems management, and public health issues are easier to understand and require less explanation. The new outcomes are well suited as a tool to educate external viewers, including pharmacy applicants and enrolled students.

Recommendation 6

The pharmacy profession as a whole must educate other health care providers and the lay public about the education and training of pharmacists. Consistency and repetition should help solidify who we are in the eyes of the lay public, other health care providers, and pharmacy applicants and students. Specific examples of how this may be achieved include publication of the 2004 CAPE Educational Outcomes in school bulletins and/or catalogs and placement on the school's Web site (with consideration of inclusion of the longitudinal schematic as stated in Recommendation 5), consistent use by all national pharmacy organizations, and consistent exhibition of the outcomes defining pharmacist education by all members of the profession.

Assessing the 2004 CAPE Educational Outcomes

Although detailed and descriptive, not all of the outcomes in the 1998 document are measurable, which hinders its utility as an assessment instrument. Suggestions for alteration of this document so that it may be useful as an assessment instrument have been documented in the pharmacy literature.10,11 Many of the general ability-based outcomes relate to personal attitudes, values, and beliefs, which although extremely valuable, may be difficult to measure, at least by conventional methods (eg, surveys or rubrics). Instruments have been developed to assess critical thinking skills, ethical judgment, cognitive moral reasoning, and professionalism of pharmacy students, and many of these instruments have been validated.12–16 To date, a conjoined, integrated tool to assess multiple abilities has not been established. Consideration of this important work should remain at the forefront if or when a national instrument is developed based on the 1998 and 2004 versions of the CAPE Educational Outcomes, NAPLEX Blueprint, and ACPE Standards and Guidelines.

Although the 2004 CAPE document is less restrictive than the 1998 CAPE document, the ability to measure the educational outcomes in the 2004 CAPE document will be difficult because they are so broadly defined. Thus, the role of the 2004 document should be simply as a broad educational tool, leaving the 1998 CAPE Educational Outcomes as a guide for the development of measurable outcomes. Since not all of the items in the 1998 CAPE Educational Outcomes are measurable, the first step would be to identify those outcomes considered essential for all students, with incorporation of these outcomes into a national assessment instrument. Individual schools could tailor this document to their needs and include school-specific outcomes as deemed necessary. Students would be held accountable to both the national and school-specific standards. Schools will need to evaluate how the new outcomes differ from those in existence. Once the school's educational outcomes are identified, and assessment instruments are developed, longitudinal evaluation of the curriculum can be initiated or resumed.

As the role of the pharmacist continues to advance, so do the experiential education components of the pharmacy curriculum. Introductory Pharmacy Practice Experiences (IPPE) and Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences (APPE) are vital components that help students make the connection between didactic coursework and their future role as pharmacists.

Similar to the mapping of the didactic curriculum to educational outcomes, it is important that the IPPE and APPE activities are also compared with the global educational outcomes. The 2003-2004 AACP Professional Affairs Committee made recommendations11 toward defining and standardizing experiential education efforts, which included the use of the 1998 CAPE Educational Outcomes. Although the assessment instrument using the 1998 CAPE Educational Outcomes is considered a rough draft, the concept has tremendous merit. Further review and refinement that includes input from national professional pharmacy organizations may facilitate the standardization of a valid and reliable assessment instrument.11 Additional strategies to assess the outcomes achieved through experiential education have been suggested in the literature.17 The incorporation of student self-assessments in conjunction with longitudinal portfolios may provide a valuable feedback loop. These endeavors may facilitate perpetual student self-improvement as well as curricular and program enhancements. Standardization of assessment instruments will allow for benchmarking, thereby expediting continuous quality improvement initiatives.

Recommendation 7

Development of nationally standardized pharmacy educational assessment instruments should be explored by individual organizations or a task force, with representation or input from interested organizations (eg, AACP, ACCP, ACPE) to be used as part of the accreditation process. The assessment tools should correlate with the Pharmacy Curricular Outcomes National Consensus Guidelines defined in Recommendation 1. A second workshop following the one described in Recommendation 1 should focus on educating administrators and faculty on the incorporation of the corresponding assessment tools at their respective schools.

Recommendation 8

Pharmacy schools should continually assess their curriculum (didactic and experiential) in relation to the Pharmacy Curricular Outcomes National Guidelines, as well as other school-specific educational outcomes, through the use, as possible, of externally validated assessment instruments.

Recommendation 9

Longitudinal evaluation of student and school progress in attaining the Pharmacy Curricular Outcomes National Guidelines using a standardized assessment instrument should facilitate continuous quality improvement efforts.

CONCLUSION

Pharmacy education and practice continue to evolve to meet health care demands. The more concise but broad format of the 2004 CAPE Educational Outcomes allows for greater institutional flexibility at the expense of clear, consistent, measurable outcomes interpreted similarly on a national level. By reviewing and implementing the 1998 and 2004 CAPE Educational Outcomes documents, in conjunction with other available pharmacy competency statements, schools may be able to develop a continually assessed and perpetually evolving pharmacy curriculum that meets the needs of a dynamic profession. To facilitate the process, the committee recommends careful consideration of the stated recommendations included in this commentary. Streamlining efforts across the nation will facilitate the development, integration, and assessment of pharmacy curricular educational outcomes, ultimately improving student performance and advancing the profession of pharmacy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank the following individuals for their contributions to the formation of this commentary: Eric Boyce, PharmD, Jeffrey Delafuente, MS, Tina Denetclaw, PharmD, Sandra Garner, PharmD, and Jill Kolesar, PharmD.

REFERENCES

- 1. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education (CAPE), Advisory Panel on Educational Outcomes. Educational Outcomes, revised version 2004. Available from http://www.aacp.org/Docs/MainNavigation/Resources/6075_CAPE2004.pdf. Accessed November 7, 2005.

- 2. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education (CAPE), Advisory Panel on Educational Outcomes. Educational outcomes, revised version 1998. Available from http://www.aacp.org/Docs/MainNavigation/ForDeans/5763_CAPEoutcomes.pdf. Accessed November 7, 2005.

- 3.Maine LL. CAPE outcomes 2004: what do pharmacists do? Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(3) Article 78. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen JL, Nahata MC, Roche VF, et al. Pharmaceutical care in the 21st century: from pockets of excellence to standard of care—report of the 2003-04 Argus Commission. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(3) Article S9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.American College of Clinical Pharmacy. ACCP white paper. A vision of pharmacy's future roles, responsibilities, and manpower needs in the United States. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20:991–1020. doi: 10.1592/phco.20.11.991.35270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy. Resource document. Continuing professional development in pharmacy. Available from http://www.pharmacycredentialing.org/ccp/cpdprimer.pdf. Accessed November 7, 2005.

- 7. National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. Updated NAPLEX blueprint and new passing standard. Available from http://www.nabp.net/ftpfiles/NABP01/Updatedblueprintinfo.pdf. Accessed November 7, 2005.

- 8.Schwinghammer T. Defining the generalist pharmacy practitioner. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(3) Article 76. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1990;47:533–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cerulli J, Malone M. Using CAPE outcome-based goals and objectives to evaluate community pharmacy advanced practice experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(2) Article 34. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Littlefield LC, Haines ST, Harralson AF, et al. Am J Pharm Educ. 3. Vol. 68. 2004. Academic pharmacy's role in advancing practice and assuring quality in experiential education: report of the 2003-2004 Professional Affairs Committee. Article S8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller DR. Longitudinal assessment of critical thinking in pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(4) doi: 10.5688/aj730466. Article 120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Latif DA. Cognitive moral development and pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64:451–4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Latif DA. An assessment of the ethical reasoning of United States pharmacy students: a national study. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(2) Article 30. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Purkerson Hammer D, Mason HL, Chalmers RK, Popovich NG, Rupp MT. Development and testing of an instrument to assess behavioral professionalism of pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64:141–51. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purkerson Hammer D. Professional attitudes and behaviors: the “As and Bs” of professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64:455–64. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beck DE. Outcomes and experiential education. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20(10 pt 2):S297–306. doi: 10.1592/phco.20.16.297s.35020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]