Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the correlation between specific prepharmacy college variables and academic success in the Texas Tech doctor of pharmacy degree program.

Methods

Undergraduate and pharmacy school transcripts for 424 students admitted to the Texas Tech doctor of pharmacy degree program between May 1996 and May 2001 were reviewed in August of 2005. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Release 11.5. The undergraduate college variables included prepharmacy grade point-average (GPA), organic chemistry school type (2- or 4-year institution), chemistry, biology, and math courses beyond required prerequisites, and attainment of a bachelor of science (BS), bachelor of arts (BA), or master of science (MS) degree. Measurements of academic success in pharmacy school included cumulative first-professional year (P1) GPA, cumulative GPA (grade point average of all coursework finished to date), and graduation without academic delay or suspension.

Results

Completing advanced biology courses and obtaining a BS degree prior to pharmacy school were each significantly correlated with a higher mean P1 GPA. Furthermore, the mean cumulative GPA of students with a BS degree was 86.4 versus cumulative GPAs of those without a BS degree which were 84.9, respectively (p = 0.039). Matriculates with advanced prerequisite biology coursework or a BS degree prior to pharmacy school were significantly more likely to graduate from the doctor of pharmacy program without academic delay or suspension (p = 0.021 and p = 0.027, respectively). Furthermore, advanced biology coursework was significantly and independently associated with graduating on time (p = 0.044).

Conclusions

Advanced biology coursework and a science baccalaureate degree were significantly associated with academic success in pharmacy school. On multivariate analysis, only advanced biology coursework remained a significant predictor of success.

Keywords: academic success, pharmacy students, grade point average, graduation, prerequisites, performance

INTRODUCTION

The mandatory educational background of applicants to pharmacy schools in the United States was debated many years before the American Conference of Pharmaceutical Faculties, known since 1925 as the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, required for the 1908-1909 academic year, “satisfactory completion of at least one year of work in an accredited high school or its equivalent.”1 Even today, admission requirements for pharmacy schools vary from 16 units of high school work for the 6-year curriculum at the University of Rhode Island College of Pharmacy to 3 years of college studies for the 4-year curriculum at the Ohio State University College of Pharmacy and University of Tennessee College of Pharmacy.2 Despite differences in admission requirements, each college or school of pharmacy strives to select the most qualified applicants. To this end, many colleges have published studies relating admissions criteria with student academic achievement in pharmacy school.3-27

Predictors of academic success in pharmacy school have included American College Test scores, Pharmacy College Admission Test (PCAT) scores, grades in specific prepharmacy courses, prepharmacy grade point average, personal interview scores, Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, California Critical Thinking Dispositions Inventory and Skills Tests, and a prior 4-year college degree.3-27 Whereas the value of grades in prepharmacy math and science courses have been confirmed by multiple studies, a prior 4-year college degree predicted success in a study by Chisholm but not in a study by Thomas.20,25 To our knowledge, no studies have evaluated the relationship between advanced prepharmacy college courses and academic success in pharmacy school. The aim of this study was to explore the association between advanced chemistry, biology, and math coursework (junior and senior level college classes beyond required prerequisites) as well as the attainment of a prior college degree (BS, BA, or MS) with academic success in pharmacy school.

The Texas Tech School of Pharmacy has offered the Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) degree as its single professional degree since the first class was admitted in 1996. The Texas Tech PharmD degree program requires at least 2 years of specific undergraduate college study followed by 4 academic years of professional pharmacy study. The required science and math prepharmacy courses include 8-10 semester hours of general chemistry with laboratory, 8-10 semester hours of organic chemistry with laboratory, 4 semester hours of general physics with laboratory, 8 semester hours of general biology with laboratory, 4 semester hours of microbiology with laboratory, 3-4 semester hours of calculus, and 3 semester hours of statistics.

Applicants are required to take the PCAT, submit transcripts from undergraduate institutions, complete a pharmacy experiential writing essay, have letters of recommendation submitted, and submit a completed application (along with an application fee). Based on these requirements, students are invited for an on-campus interview. During the interviews, students are required to take the California Critical Thinking Skills Test, complete a writing sample, participate in a group patient problem-solving session, and undergo interviews by faculty members and students. The Student Affairs Committee conducts a comprehensive review of each candidate who completed the on-campus interview and then selects applicants for admission into the PharmD program.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects (IRB number: A05 – 3284). Undergraduate and pharmacy school transcripts for 424 students admitted to the Texas Tech PharmD program between fall 1996 and the fall 2001 were reviewed in August 2005. This timeframe was chosen because by August 2005, students admitted in fall 2001 could be differentiated as either having graduated in May 2005 or having been academically delayed or suspended. The prepharmacy variables used in this study were as follows: prepharmacy grade point average calculated only from required preprofessional courses; organic chemistry taken at a 2-year or a 4-year institution, chemistry courses beyond required prerequisites, biology courses beyond required prerequisites, math courses beyond required prerequisites, bachelor of science degree, bachelor of arts degree, and master's degree. Measurements of academic success in pharmacy school included cumulative first-professional year grade point average (P1 GPA), cumulative grade point average of all coursework finished to date (cumulative GPA), and graduation without academic delay or suspension. GPA is reported on a numerical scale from 0 to 100 rather than letter grades. Correlations between prepharmacy variables and measurements of academic success in pharmacy school were evaluated for the 424 admitted students and for the 389 graduates of the Texas Tech PharmD program.

Student data were initially transcribed to an Excel spreadsheet, and then converted for analysis with SPSS Release 11.5. Character data were encoded numerically when needed. For quality assurance, frequency distributions for all variables included in the research study were verified for reasonableness. Furthermore, the data were cleaned to provide quality assurance that there were no transcription errors in the data. Following data validation, basic descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations, and percentages were produced. Inferential statistical tests were also employed. The Chi square test was used with nominal data. The independent-samples t test was used with continuous data. Bivariate correlations, including Pearson's and point biserial, were computed to test the magnitude and direction of relationships between variables.

Multivariate methods were used to assess the impact of covariates. Stepwise multiple regression was used for analyses involving continuous dependent variables; logistic regression with forward selection was used for analysis involving a binary dependent variable. Dummy variables were created for categorical independent variables. To verify the appropriateness of the resultant regression models, the correlation matrix for the independent variables and the variance inflation factors were examined for multicollinearities; no problems were detected. For all analyses, the a priori level of significance was 0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 424 admitted students, 162 (38%) had taken advanced chemistry coursework, 255 (60%) had taken advanced biology coursework, and 98 (23%) had taken advanced math coursework prior to pharmacy school. Furthermore, 144 students (34%) had earned a BS degree prior to pharmacy school; 38 students (9%), a BA degree; and 12 students (3%), an MS degree. The most frequent additional chemistry courses included analytical chemistry methods and laboratory, biological chemistry, and molecular biochemistry. The most common additional biology courses included genetics, cell biology, immunology, biochemistry, and molecular biology. The most common additional math courses were calculus II, calculus III, differential equations, and advanced statistics. Some institutions categorized biochemistry under the department of chemistry and others under the department of biology. Therefore, this course was categorized in our study as either

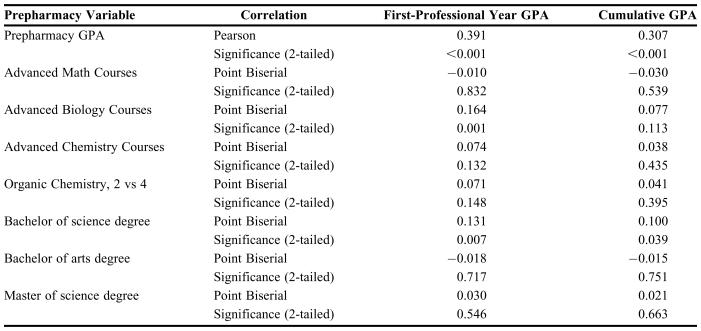

Among all students admitted to the PharmD program (N = 424), prepharmacy GPA, taking advanced courses in biology, and earning a BS degree prior to pharmacy school were significantly associated with a higher mean P1 GPA (Table 1). The mean P1 GPA of admitted students with advanced prerequisite biology courses was 84.0 compared to 81.5 for those without advanced biology courses (p = 0.001). The mean P1 GPA of admitted students who had earned a BS degree prior to pharmacy school was 84.3 compared to 82.2 for those who had not earned a BS degree (p = 0.007). Additionally, earning a BS degree prior to pharmacy school was significantly associated with a higher mean cumulative GPA among all admitted students (Table 1). The mean cumulative GPA among all admitted students who earned a BS degree prior to pharmacy school was 86.4 compared to 84.9 for those who did not (p = 0.039). Also presented in Table 1, advanced math, advanced chemistry, organic chemistry taken at a 2- or 4-year institution, BA, and MS were not significantly correlated with GPA among all admitted students.

Table 1.

Correlation Between Prepharmacy Variables and Grade Point Average in Pharmacy School (N = 424)

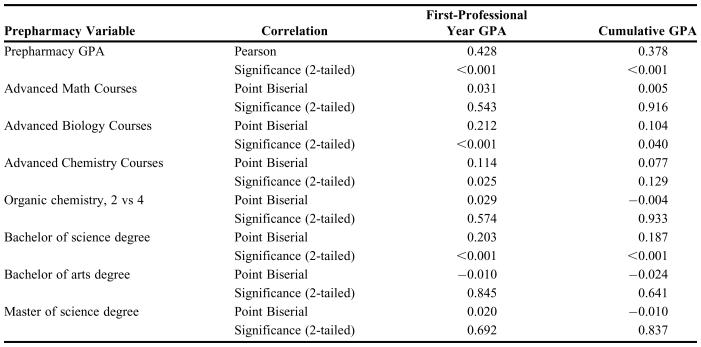

Among graduates of the PharmD program (n = 389), prepharmacy GPA, advanced biology, advanced chemistry, and attaining a BS degree were significantly associated with a higher mean P1 GPA (Table 2). The mean P1 GPA of graduates with advanced prerequisite biology courses was 84.9 compared to 82.5 among those without those courses (p < 0.001). The mean P1 GPA of graduates with advanced prerequisite chemistry courses was 84.7 compared to 83.4 among graduates without those courses (p = 0.025). The mean P1 GPA of graduates who earned a BS degree prior to pharmacy school versus those who had not was 85.5 and 83.1, respectively (p < 0.001). Furthermore, having taken advanced biology courses prior to starting pharmacy school and earning a BS degree were significantly associated with a higher mean cumulative GPA. The mean cumulative GPAs of graduates who had completed advanced prerequisite biology courses prior to pharmacy school versus those who had not were 86.91 and 85.98, respectively (p = 0.04), and the mean cumulative GPA of graduates with versus without a BS degree was 87.7 and 86.0, respectively (p < 0.001). Also presented in Table 2, advanced math, organic chemistry taken at a 2- or 4-year institution, BA, and MS were not significantly correlated with GPA among graduates.

Table 2.

Correlation Between Prepharmacy Variables and Grade Point Average in Pharmacy School Among All Graduates (N = 389)

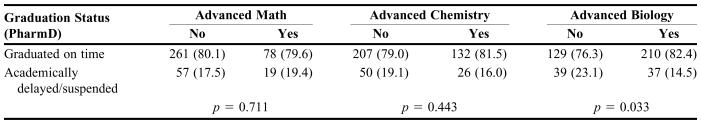

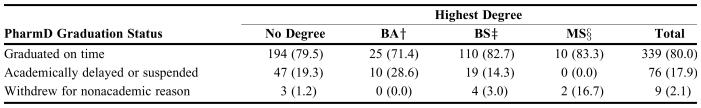

Completing advanced prepharmacy biology coursework, was significantly associated with a higher likelihood of graduating on time and avoiding academic delay or suspension (p = 0.033) than taking advanced prepharmacy math or chemistry courses, (Table 3). The prevalence of academic delay or suspension among PharmD students who had taken advanced biology coursework versus those who had not was 14.5% and 23.1%, respectively, for an absolute difference of 8.6%. Additionally, the attainment of a prepharmacy college degree was significantly correlated with graduating from the PharmD program on time and avoiding an academically delayed graduation or academic suspension (Table 4). However, the rate of a delayed graduation or suspension for academic reasons was higher among those students with a prior BA degree (28.6%) than those without a prior degree (19.3%). Also of note in Table 4, among the 12 students with a master's degree prior to pharmacy school, none were academically delayed or suspended; although 2 withdrew for nonacademic reasons.

Table 3.

Association Between Completing Advanced Prepharmacy Courses and Graduation Status from Pharmacy School, No. (%)

Table 4.

Students Stratified by Highest Prepharmacy College Degree and PharmD Graduation Status, No. (%)*

Significant correlation between highest prepharmacy college degree and PharmD graduation status (p = 0.007)

†One student earned a BS and then a BA during prepharmacy college studies

‡One student earned a BA and then a BS during prepharmacy college studies

§Ten students earned a BS and 2 students earned a BA prior to a MS degree

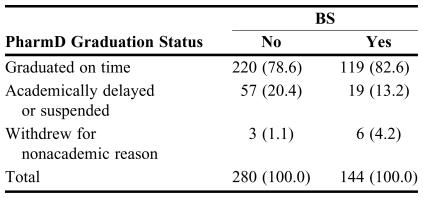

Earning a bachelor of science degree prior to pharmacy school was significantly associated with graduating on time and avoiding academic delays or suspension in the PharmD program (p = 0.027), (Table 5). The prevalence of academic delay or suspension among PharmD students with a BS degree versus those without one was 13.2% and 20.4%, respectively, for an absolute difference of 7.2%.

Table 5.

Students With and Without a Bachelor of Science Degree Stratified by PharmD Graduation Status, No. (%)*

Significant correlation between prior BS degree and PharmD graduation status (p = 0.027)

Multivariate statistical analyses were employed to control for covariates. Stepwise multiple regression produced a model (F(2, 414) = 56.856, p < .001; R2 = 0.215) which yielded the finding that independent variables associated with P1 GPA were prepharmacy GPA (β = .422, p < 0.001) and completion of advanced biology courses prior to pharmacy school (β = .251, p < 0.001). Additionally, stepwise multiple regression generated a model (F(2, 417) = 26.903, p < 0.001; R2 = 0.114) which demonstrated that independent variables associated with cumulative GPA were prepharmacy GPA (β = 0.324, p < 0.001) and taking advanced biology courses (β = 0.143, p = 0.002). Logistic regression produced a model (χ2(2) = 11.058, p = 0.004) which showed that independent variables associated with the odds of graduating on time were prepharmacy GPA (Exp(β) = 2.6 , p = 0.005) and taking advanced biology courses (Exp(β) = 1.7 , p = 0.044). The consistency of these findings suggests that prepharmacy GPA and advanced biology courses are the best predictors of student outcomes among the variables under consideration.

DISCUSSION

The present study confirmed previous study results, such as the association between prepharmacy GPA and a higher mean P1 GPA and cumulative GPA. This study also demonstrated new findings. For example, that a prior BS degree but not a prior BA degree was significantly associated with academic success in a PharmD program may explain the disparity in the observations by Chisholm and Thomas in relation to a prior 4-year college degree predicting academic achievement in pharmacy school.20,25 The type of prior degree earned by a school of pharmacy applicant appears to be an important distinguishing factor. However, the knowledge, maturity, and experiences gained by completing a BA degree are arguably beneficial in many ways other than an improved pharmacy school GPA. For example, an association between a prior BA degree and leadership roles within student pharmacy organizations might be an interesting area of future research.

Although having obtained a prior BS degree was statistically significant, the academic significance of an absolute difference in P1 GPA of 2.1% and cumulative GPA of 1.5% among pharmacy students with such a degree versus those without is questionable. This question centers on whether a statistically significant difference in GPA is practically significant. Beyond academic significance, the hypothesis that these differences in pharmacy school GPA are associated with greater practice success after graduation is tenuous and unproven. Nevertheless, the significant difference in rates of academic delay or suspension between pharmacy students with a prior BS degree versus those without a BS degree is a more practically significant finding than GPA differences. Specifically, the observed absolute difference of 7.2% in the rate of academic delay or suspension between these students means that for every 14 matriculates admitted to pharmacy school with a prior BS degree, 1 case of academic delay or suspension may be avoided.

In the present study, advanced chemistry coursework was only significantly associated with a higher mean P1 GPA among PharmD graduates rather than all students admitted into the PharmD program. Whereas advanced biology coursework was significantly associated with a higher mean P1 GPA among all students admitted and among graduates, a higher mean cumulative GPA among graduates, and graduation without academic delay or suspension. This observed absolute difference of 8.6% in the rate of academic delay or suspension among these students means that for every 12 matriculates admitted to pharmacy school with advanced biology coursework, 1 case of academic delay or suspension may be avoided. Furthermore advanced biology coursework was statistically and independently associated on multivariate analysis with academic success in pharmacy school. The stronger association between advanced biology coursework (rather than advanced chemistry coursework) and academic success in pharmacy school may be a reflection of the Texas Tech School of Pharmacy curriculum. For example, the Texas Tech PharmD program emphasizes biology sciences. Based upon the consistency of advanced biology coursework on univariate and multivariate analysis to predict academic success in pharmacy school, the Texas Tech faculty members approved a motion by the Student Affairs Committee to add advanced biology coursework as an evaluative factor in the admission process.

Several observations in this study need to be confirmed by additional research. For example, the effect of a prior MS degree upon pharmacy school success requires a larger sample size than the present study. Additionally, students who took organic chemistry prerequisites at a 4-year institution versus students who took organic chemistry coursework at a 2-year institution did not significantly achieve greater academic success in pharmacy school in this study. This observation is relevant because pharmacy school admissions committees often must compare applicants with educational backgrounds from 2-year and 4-year institutions. The comparison between pharmacy school applicants with an educational background at a 2-year versus a 4-year institution needs to be further studied. Furthermore, several studies have documented the significance of prepharmacy math GPAs toward achieving success in pharmacy school; however, our study did not reveal any benefit from advanced mathematics coursework.10,19,21 The results of our study add clarity to math prerequisites for pharmacy school. While the grade attained in 3 semester hours of college calculus and statistics may predict academic success in pharmacy school, additional mathematics coursework may not be of any further benefit. Another suggested area for future research would be an evaluation of the impact of the number of credit hours of advanced prepharmacy coursework on academic success in pharmacy school. For example, would an admit with more advanced credit hours (eg, 9 credits) in advanced biology courses perform better in pharmacy school than an admit with less advanced credit hours (eg, 3 credits)?

Limitations

Since the research design was retrospective, random selection of subjects and random assignment of subjects to treatments could not be implemented. Accordingly, a true experimental design could not be achieved. Given this limitation, causality can not be established. Additionally, it is possible that confounding variables not included in the analyses exist. The findings may not be readily generalized to other institutions or student populations that are not similar to Texas Tech with respect to student demographics, faculty characteristics, and program requirements. Further research, including replication using different student populations or different environments, may serve to strengthen the validity of the findings of this study.

CONCLUSIONS

Pharmacy school applicants with advanced college biology coursework or a BS degree were significantly more likely to have a higher P1 GPA and cumulative GPA than students without this education background. Applicants who had taken advanced biology courses or attained a BS degree were significantly more likely to graduate on time without academic delay or suspension compared to their counterparts. Furthermore, advanced biology coursework was significantly and independently associated with graduating on time without academic delay or suspension. These results, especially if validated by other pharmacy programs, may assist admissions committees in making a more informed decision in selecting the most qualified applicants, and in determining college coursework admission requirements.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sonnedecker G. Kremers and Urdang's History of Pharmacy. 4th edition. Madison, WI: AIHP Publications; 2003. The development of education; pp. 226–54. [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Pharmacy school admission requirements. Available at: www.aacp.org/Docs/MainNavigation/InstitutionalData/6871_School_Narratives_PSAR.pdf. Accessed November 28, 2005.

- 3.Munson JW, Bourne DWA. Pharmacy college admission test (PCAT) as a predictor of academic success. Am J Pharm Educ. 1976;40:237–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kotzan JA, Entrekin DN. Validity comparison of PCAT and SAT prediction of first-year GPA. Am J Pharm Educ. 1977;41:4–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liao WC, Adams JP. Methodology for the prediction of pharmacy student academic success. I: preliminary aspects. Am J Pharm Educ. 1977;41:124–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Popovich NG, Grieshaber LD, Losey MM, Brown CH. An evaluation of the PCAT examination based academic performance. Am J Pharm Educ. 1977;41:128–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lowenthal W, Wergin J, Smith HL. Predictors of success in pharmacy school: PCAT versus other admission criteria. Am J Pharm Educ. 1977;41:267–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munson JW, Bourne DWA. Pharmacy college admission test (PCAT) as a predictor of academic success. II: a progress report. Am J Pharm Educ. 1977;41:272–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacoby KE, Plaxco WB, Kjerulff K, Weinert AB. The use of demographic background variables as predictors of success in pharmacy school. Am J Pharm Educ. 1978;42:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torosian G, Marks RG, Hanna DW, Lepore RH. An analysis of admission criteria. Am J Pharm Educ. 1978;42:7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowenthal W, Wergin J, Smith HL. Correlation of a biopharmaceutics grade and calculation scores in pharmacy school and arithmetic skills and mathematical reasoning subscores in the pharmacy college admission test. Am J Pharm Educ. 1978;42:26–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowenthal W, Wergin JF. Relationship among student preadmission characteristics, NABPLEX scores, and academic performance during later years in pharmacy school. Am J Pharm Educ. 1979;43:7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palmieri A. Multivariate prediction of academic success of transfer students. II: evaluation of the predictor equations. Am J Pharm Educ. 1979;43:110–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowenthal W. Relationships among student admission characteristics, licensing examinations and didactic performance: comparison of three graduating classes. Am J Pharm Educ. 1981;45:132–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman CB, Lage G, Norwood J, Stewart J. Predictive validity of the pharmacy college admission test. Am J Pharm Educ. 1987;51:288–91. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bandalos DL, Sedlacek WE. Predicting success of pharmacy students using traditional and nontraditional measures by race. Am J Pharm Educ. 1989;53:145–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowenthal W, Meth H. Myer-Briggs type inventory personality preferences and didactic performance. Am J Pharm Educ. 1989;53:226–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charupatanapong N, McCormick WC, Rascati KL. Predicting academic performance of pharmacy students: demographic comparisons. Am J Pharm Educ. 1994;58:262–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chisholm MA, Cobb HH, Kotzan JA. Significant factors for predicting academic success of first-year pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 1995;59:364–70. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chisholm MA, Cobb HH, Kotzan JA. Prior four year college degree and academic performance of first year pharmacy students: a three year study. Am J Pharm Educ. 1997;61:278–81. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chisholm MA, Cobb HH, Dipiro JT, Lauthenschlager GJ. Development and validation of a model that predicts the academic ranking of first-year pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 1999;63:388–94. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen DD, Bond CA. Prepharmacy indicators of success in pharmacy school: grade point averages, pharmacy college admission test, communication abilities, and critical thinking skills. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21:842–9. doi: 10.1592/phco.21.9.842.34566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hardigan PC, Lai LL, Arneson D, Robeson A. Significance of didactic merit, test scores, interviews and the admissions process: a case study. Am J Pharm Educ. 2001;65:40–3. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelley KA, Secnik K, Boye ME. An evaluation of the pharmacy college admissions test as a tool for pharmacy college admissions committees. Am J Pharm Educ. 2001;65:225–30. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas MC, Draugalis JR. Utility of the pharmacy college admission test (PCAT): implications for admissions committees. Am J Pharm Educ. 2002;66:47–51. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kidd RS, Latif DA. Traditional and novel predictors of classroom and clerkship success of pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(4):Article 109. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Houglum JE, Aparasu RR, Delfinis TM. Predictors of academic success and failure in a pharmacy professional program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69:Article 43. [Google Scholar]