Abstract

Objective

To develop a Professional Skills Enhancement Workshop (PSEW) to assist practitioners who require skills training to maintain competency and meet new standards of practice. Participants for this workshop were identified as those pharmacists who completed the peer review assessment process and who did not meet standards of practice expectations.

Design

The full-day workshop consists of a half-day introduction to use of clinical drug information resources and approaches to addressing practice-based questions. The second part of the workshop introduces participants to the use of structured patient-interviewing techniques to elicit information using standardized patients. Participants in the workshop completed self-assessments as well as course evaluations. Subsequent to completion of the course, participants rechallenged the peer review assessment process, a test of their clinical skills consisting of a written test of clinical knowledge and an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE), to provide objective evidence of skills acquisition.

Assessment

Over 90% of participants “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the PSEW was helpful in reacquainting them with current standards of professional practice. Sixty-nine percent of participants who completed the peer review assessment rechallenge process following completion of the course were able to meet standards of practice expectations.

Conclusions

In developing continuous professional development programs, first identifying the needs of all practitioners is essential. The PSEW provides one model for skills training for practitioners who, for a variety of reasons, may not have maintained the expected level of competency.

Keywords: continuous professional development, quality assurance, pharmacy education, pharmacy practice

INTRODUCTION

Continuous professional development (CPD) has become a significant issue for regulators and educators in the health professions, including pharmacy.1 Over the course of a decades-long career, professionals must not only acquire new knowledge and skills as scientific knowledge and social values evolve, but must also maintain existing competencies to ensure there is no deterioration in their abilities.2–6

In some cases, new knowledge development may require development of significant new skills, such as patient interviewing or physical assessment, which may not have been taught during initial training.4 Upon graduation, pharmacists rely on available continuing education programming which may or may not address development of a needed skill set. This can potentially leave gaps in the development of skills required to meet current standards of practice in older practitioners.3

Within the profession of pharmacy, issues affecting competency can be particularly problematic since many pharmacists tend to work alone, without benefit of peer support or benchmarking from other pharmacists.3 Consequently, as described by a pharmacist in previous research, “…the last time I saw someone do my job was when I was in school….How do I know if I'm doing it right anymore?”3

Providing a mechanism for individuals to assess their continuous professional development activities, to allow them to benchmark themselves vis-à-vis their peers in practice, has been identified as a particularly important strategy for ongoing maintenance of competency.7–9 In Ontario, Canada, the Ontario College of Pharmacists (OCP, the licensing and regulatory body for the profession) implemented a structured quality assurance practice review process in 1996.10,11 This process permits pharmacists to assess the quality of their practice and their individual continuous professional development activities.

Since its inception in 1996, over 1500 pharmacists (representing approximately 15% of patient-care providers in the province) have been randomly selected to complete the practice review. Approximately 87% of pharmacists have been able to meet expectations on the first attempt and were placed in the “self-directed” category with respect to their continuous professional development activities. Thus, these pharmacists received objective evidence that they have demonstrated an appropriate level of professional competence, providing reassurance that their CPD activities are indeed adequate. These individuals are encouraged to continue their professional development.

Approximately 13% of those randomly selected to complete the practice review do not meet expectations and are consequently placed in the “peer support” category with regard to their continuous professional development activities. These individuals are required to submit a written education action plan to indicate how they will address knowledge and/or skills gaps identified through the practice review process. This action plan consists of specific learning objectives, timelines, and outcome indicators, and complements the individual's own learning portfolio. The Ontario College of Pharmacy provides support and encouragement to the individual throughout this process, and will arrange reassessment (or “re-challenge”) through the practice review process.

There are several groups who may be at higher risk of being designated to the peer support category. In particular, pharmacists who have been graduated 25 years or more (25+) and international pharmacy graduates (IPGs) have a higher likelihood of being designated to this category.10,12 Research is currently underway to identify reasons for this finding. For those in the peer support category, specific knowledge and skills gaps have been identified as common areas of concern:

difficulty in gathering relevant and appropriate information from a patient, or selecting appropriate facts from a written clinical case;

difficulty in framing a clinical question or problem in practice;

difficulty in identifying and prioritizing actual or potential drug-related problems;

lack of understanding of how to use tertiary reference textbooks;

inefficient or ineffective use of drug information resources, including patient information leaflets;

incomplete application of scientific information to resolve actual or potential drug-related problems;

suboptimal communication skills (including verbal, non-verbal, and empathic skills); and

unawareness of professional requirements related to monitoring and follow-up of patients.

Many individuals in the peer support category may have other unique needs (for example, unawareness of new laws and regulations, or specific therapeutic knowledge deficits); the gaps identified above represent the common learning needs of virtually all those directed to the peer support category.

In an effort to address these common knowledge and skills gaps of the “peer support” group, and to evaluate the value of peer-driven CPD, OCP began offering the Professional Skills Enhancement Workshop (PSEW) in 2002. In large part, this workshop was developed in recognition of the value of peer-supported learning. Rather than have individuals work alone on an educational action plan, PSEWs create an environment in which individuals with similar challenges can meet, share experiences, and work together on solving mutual problems. Recognizing the value of peer-benchmarking in learning, and to help pharmacists (most of whom work by themselves or with pharmacy technicians only) understand how their peers “do their job” and maintain competency, the PSEW was initiated.

DESIGN

The PSEW is designed as primer for CPD, and is intended to provide a platform for ongoing life-long learning. While the vast majority of PSEW participants will be required to be reassessed at the practice review, the workshop is not designed as an “exam prep” course to assist people in passing the peer-review assessment process. Instead, the course addresses common, core knowledge and skills gaps using peer-teaching methods, and provides a supportive environment in which individuals are able to disclose their unawareness of and discomfort with required skills in pharmacy practice. The knowledge and skills gaps addressed in the PSEW are fundamental in nature.

A curricular blueprint for the PSEW was developed based on the knowledge and skills gaps identified previously. Learning objectives for the PSEW are presented in Appendix 1. To facilitate interaction with participants, the workshop was designed to accommodate 12-16 candidates only.

The workshop is divided into 2 half-day sessions, broadly reflective of the 2 different assessment processes used in the practice review. In part I of the workshop, a review of clinical references (textbooks, guidelines, formularies, etc) is presented and effective drug information searching and retrieval strategies are modeled. Working in small groups with a volunteer pharmacist-mentor, individuals have an opportunity to practice using references to answer questions, and to gain familiarity with optimal search strategies (for example, efficient use of indices and tables of contents, alternative search terms, etc). Next, participants work in small groups with a pharmacist-mentor to frame and identify clinical questions and drug-related problems, then use references to address these issues. The focus is on clarifying and specifying clinical questions, and using references to answer those questions. During the course of this section, participants work together through 3 major cases involving 12 clinical questions and drug-related problems. Through the process, participants are encouraged to keep a reflective log, and to note key learning points that will assist them in practice. For part I of the workshop, a pharmacist-facilitator is utilized and 1 pharmacist-mentor is available for each group of 8 participants.

In part II of the PSEW, the focus is on pharmacist-patient interactions. A team of simulated patients leads the group through a “think-pair-share” exercise in which participants generate elements of effective patient-pharmacist interactions. As participants generate their list individually, first in pairs and then as a group, they are able to both acknowledge their individual and collective strengths and safely identify knowledge gaps. Barriers are also identified, usually basic beliefs, which have historically prevented participants from developing the skills required for contemporary practice, for example, a belief that only physicians should educate patients about medications. The elements of effective and efficient patient interviewing are modeled by a pharmacist-mentor to allow participants an opportunity to actually see how pharmacists interview patients, identify potential and actual drug-related problems, educate patients, make clinical decisions, and engage in monitoring and follow up. A “stop-start” technique is used in this modeling to allow participants an opportunity to ask the pharmacist-mentor questions about his/her approach, and to provide an opportunity to “get inside the head” of the pharmacist and the patient. Following these modeling exercises, participants reflect upon their own interviewing techniques, and identify specific strategies they need to implement to improve their professional practice.

Next, each participant has an opportunity to conduct at least 1 interview with a standardized patient, receive feedback, and observe at least 3 other interviews undertaken by other participants who also receive feedback. During this time, standardized patients and pharmacist-mentors provide copious formative feedback to each candidate. Importantly, participants engage in delivery of structured, behaviorally focused formative feedback so they may learn how to apply assessment criteria for patient interviewing. In part II of the PSEW, 1 standardized-patient educator per 6-8 participants is required, along with 1 pharmacist-facilitator for the entire group.

Following part II, candidates are provided with an opportunity to reflect upon their experience and identify specific learning objectives upon which they will focus when they return to their practice. In particular, individuals are encouraged to identify no more than 3 distinct strategies they will implement immediately and carry forward. These learning plans and strategies are documented and are made part of the individual's educational action plan. At the end of each PSEW, all candidates complete a program evaluation form that is utilized by program planners to refine delivery of the workshop in the future.

No special rooms, resources, or video equipment are required for the PSEW. Ordinary classrooms, meeting rooms, and/or offices are utilized for the large group and small group sessions. There has been considerable interest in videotaping interviews as a powerful learning tool that could be provided to each candidate so they could later observe their performance. At the current time, resource and logistics constraints preclude videotaping, but this may be considered in the future. An important part of the educational environment of this workshop is the context within which it operates. The PSEW is designed as a one-day workshop to enable individuals to attend and to participate. A fundamental goal of the workshop is to assist individuals in self-identifying learning gaps and needs that may have contributed to their suboptimal performance in the practice review. In designing the PSEW, it was recognized that a 1-day workshop could not address learning gaps that have evolved over decades of practice; however, as part of an overall system of remedial education and skills enhancement, the PSEW provides an important bootstrap to assist individuals in developing new skills in self-assessment, reflective practice, and learning plan development.

Each candidate in the PSEW was asked to complete and submit a post-program evaluation in which they indicated the quality and value of the program in improving their professional skills. This anonymous survey instrument was completed at the end of the workshop. An additional anonymous mail-out survey instrument was distributed 12-18 months following completion of the workshop. The focus of this survey instrument was to determine the impact of the workshop on professional practice.

ASSESSMENT

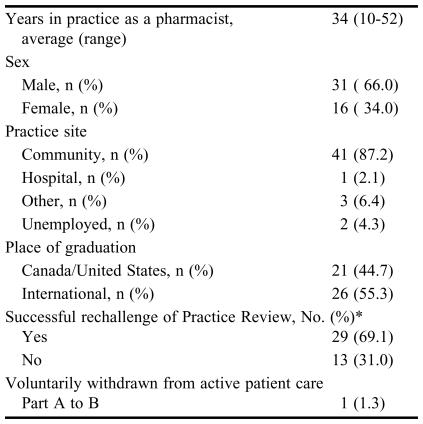

The demographic profile of PSEW participants is presented in Table 1. As indicated, these individuals had typically been in practice for many years, and consequently were never formally taught how to use many of the resources and reference sources currently in use, nor the more patient-centered care approach to practice that is currently expected. For example, many participants in the PSEW graduated at a time or in a place where pharmacists were forbidden to discuss side effects of medications with patients for fear of “putting ideas into their heads.”

Table 1.

Demographic Profile of Participants in a Professional Skills Enhancement Workshop for Pharmacists, N = 47

*Of the 47 participants, 42 had rechallenged the examination since attending the PSEW

A variety of program evaluation strategies were undertaken to assess the quality and impact of the PSEW. While the goal of the PSEW was not simply to prepare candidates for an examination, it was expected that candidates who were taught standards of practice ought to perform better on the Practice Review, which was constructed to evaluate standards of practice. As indicated in Table 1, close to 70% of those attending the PSEW passed the practice review on the next attempt.

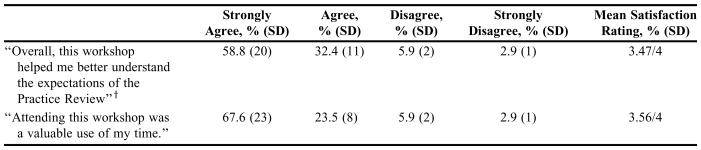

Responses to key questions on the postprogram evaluation and participant comments are provided in Table 2. As indicated, satisfaction with the workshop was generally high, with candidates indicating a strong commitment to continuous professional development upon completion.

Table 2.

Satisfaction of Participants With a Professional Skills Enhancement Workshop (n = 34*)

*34 of 47 participants completed the survey instrument

†Practice Review expectations reflect current Standards of Practice

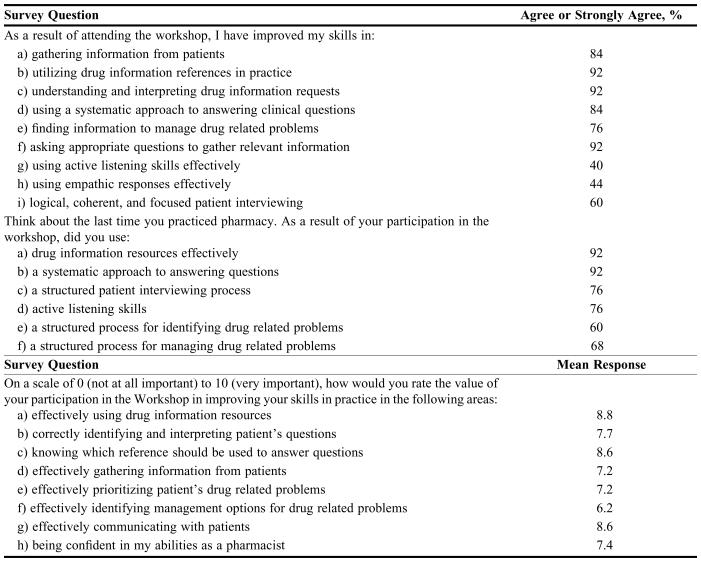

Results of an additional anonymous mail-out survey instrument are presented in Table 3. Participants reported participation in the workshop was an important tool for improving knowledge and skills related to pharmacy practice, particularly those related to interviewing patients, gathering information, and utilizing appropriate references/resources.

Table 3.

Pharmacists’ Responses to a Survey Conducted 12-18 Months Following Completion of a Professional Skills Enhancement Workshop, n = 25

* 34 of 47 participants completed the postworkshop survey instrument

DISCUSSION

Continuous professional development needs of practitioners vary considerably. While the focus for many providers of CPD tends to be on the new, innovative, cutting-edge developments in biomedical sciences, there is clearly a need for CPD of a more remedial nature. In every profession, there are individuals who, for a variety of reasons, have fallen behind their peers in terms of CPD. In many professions, and particularly in pharmacy, the tradition of the sole practitioner may allow these individuals to mask fundamental knowledge and skills gaps for many years. As with many learning situations, these individuals may be particularly vulnerable to a tailspin phenomenon: the further they lag behind their peers in terms of CPD, the less likely they are to catch up. As a result, some practitioners in practice today may lack some of the basic practice skills that first- or second-year students are expected to demonstrate.

As a profession, pharmacy has an option to either ignore the problem, excise these individuals from their livelihood for not meeting standards of practice, or work collaboratively with them to assist them in remedial CPD. The goal of this type of CPD is not necessarily to produce exemplary practitioners, but rather to allow individuals who have fallen behind standards and expectations to catch up to their peers. Also, there is the hope that, going forward, they will maintain their competency through more rigorous attention to their individual learning needs.

The PSEW model is unique insofar as it is aimed at a group of practitioners traditionally overlooked by most CPD providers. It is also aimed at individuals who have been assessed by their regulatory body as not currently meeting standards and therefore requiring peer support in their CPD activities. The combination of modeling, mentoring, and structured curricular intervention appears to be successful in assisting many individuals in meeting standards of practice requirements, passing Practice Review assessments, and allowing them to re-establish themselves on a level playing field with their peers.

The group that is targeted with the PSEW is large and heterogenous, and represents a significant percentage (∼15%) of all pharmacists involved in patient care in Ontario. This is a group that traditionally has “flown under the radar,” and whose learning needs have not been identified nor their progress followed. By developing a supportive, peer-driven process, the PSEW allows these individuals to disclose learning needs in a safe environment; receive formative feedback from peers, mentors, and standardized patients; and develop skills that are new for them (but now commonplace expectations in the profession).

The survey distributed 12-18 months following completion of the Workshop provides some indication that learning in the PSEW translates into practice. Both survey instruments were based on self-reporting; consequently issues related to recall bias or difficulties with accurate self-appraisal may have biased results. In addition, while survey instruments were anonymous and confidentiality was assured throughout the process, individuals involved may have felt a need to demonstrate support for the workshop since it was part of the regulatory process. These potential issues must be considered in interpreting results. Further work is underway to determine value of the workshop through more objective means, including in-site assessments and structured clinical evaluations using standardized patients.

The educative-remedial approach to professional skills enhancement, rather than a punitive-retributive approach (such as imposing terms and limitations on a license to practice, or revoking a license completely), provides an opportunity to assist pharmacist who have fallen behind in meeting current standards and expectations. Given the large number of individuals in this group, their diverse learning needs and challenges, and the importance of not simply ignoring the dimensions of this situation, the PSEW provides an interesting CPD model for regulators and educators in the health professions.

CONCLUSION

The needs of practitioners who have been identified as not meeting standards of professional practice are diverse; however, through the peer-review assessment process a variety of common learning gaps have been identified. These learning gaps were utilized as the basis of an educational remedial workshop designed to provide pharmacists with an opportunity to update their basic skills. The PSEW is a peer-supported model of professional skills development that focuses on 2 major practice-specific activities: framing, clarifying, and addressing clinical questions and patient interviewing techniques. Participants reported a high degree of satisfaction with the workshop and its design, and indicate that it provided them with new, transferable skills and knowledge that improved their professional practice. Close to 70% of participants who completed a rechallenge test following completion of the workshop were able to meet standards of practice expectations, further indicating the value of this educational approach to improving pharmacists’ patient care skills.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Della Croteau, Chris Schillemore, and Sarah Boudreau from the Ontario College of Pharmacists, and Cathy Smith from the Standardized Patient Program at the University of Toronto.

Appendix 1. Learning Objectives for Professional Skills Enhancement Workshop

Part 1: Dealing with Clinical Questions

Upon completion of this Module, participants will be able to:

➢ Apply a systematic analytic process to defining a clinical question

➢ Utilize an appropriate literature search technique to address a clinical question

➢ Effectively integrate information from a variety of sources to answer clinical questions

➢ Demonstrate reflective practice skills in identifying personal learning needs

In this module, participants will utilize real-world practice-based scenarios as prompts for framing clinical questions, and will utilize a variety of medical information literature sources to appropriately respond to these questions. Throughout the module, individuals will reflect upon their own learning needs and develop a learning plan to assist them in continuing professional development in the context of their own practice.

Part 2: Patient Interviewing Skills

Upon completion of this Module, participants will be able to:

➢ Describe a systematic framework for information gathering from patients

➢ Utilize appropriate verbal and non-verbal communication techniques to elicit information from patients in an effective, efficient, and patient-centred manner

➢ Demonstrate appropriate patient-centred interviewing skills including empathic communication, focus, logic, and coherence

➢ Demonstrate reflective practice skills in identifying personal learning needs

In this module, participants will work closely with simulated patient educators to identify personal strengths and areas of improvement with respect to patient interviewing skills. Participants will have an opportunity to observe and participate in a variety of patient interviewing activities, and will receive extensive feedback on their skills from pharmacists and simulated patient educators. Throughout the module, individuals will reflect upon their own learning needs, and develop a learning plan to assist them in continuing professional development within the context of their own practice.

REFERENCES

- 1.International Pharmaceutical Federation. The Netherlands: The Hague; 2002. Statement of professional standards on continuing professional development. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown JO. Know thyself: the impact of portfolio development on adult learning. Adult Educ Q. 2002;52:228–45. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Austin Z, Marini A, Macleod Glover N, Croteau D. Continuous professional development: a qualitative study of pharmacists’ attitudes, behaviours, and preferences in Ontario, Canada. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(1):Article 4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mezirow J. On critical reflection. Adult Educ Q. 1998;48:185–98. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epstein RM. Mindful practice. JAMA. 1999;282:833–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jolly B. Clinical logbooks: recording clinical experiences may not be enough. Med Educ. 1999;33:86–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norcini J. Recertification in the medical specialities. Acad Med. 1993;69(10 Suppl):s90–s94. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199410000-00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Page G, Bates J, Dyer S, Vincent D, Bordage G, Jacques A, Sindon A, Kaigas T, Norman G. Physician assessment and physician enhancement programs in Canada. Can Med Assoc J. 1995;153(12):1723–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LaDuca A, Leone-Perkins M, de Champlain A. Evaluating comtinuing competence of physicians through multiple assessment modalities: the physicians’ continued competence assessment program. Acad Med. 1997;72(5):457–8. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199705000-00100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Austin Z, Marini A, Croteau D, Violato C. Assessment of pharmacists’ patient care competencies: validity evidence from Ontario (Canada)’s Quality Assurance and Peer Review Process. Pharm Educ. 2004;4:23–32. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Austin Z, Croteau D, Marini A, Violato C. Continuous professional development: the Ontario experience in professional self-regulation through quality assurance and peer review. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67:Article 56. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Austin Z. Continuous professional development and foreign-trained health care professionals: results of an educational needs assessment of international pharmacy graduates in Ontario (Canada) J Soc Admin Pharm. 2003;20:232–41. [Google Scholar]