Abstract

Effective interpersonal communication skills are needed for pharmacists to deliver patient-centered care. To achieve this outcome with pharmacists, communication skills are emphasized in pharmacy school in required coursework, such as a clinical communication course. One important concept to include in communication coursework is content on perceptions because perceptions influence communication interactions. Specific emphasis should include a focus on self-perceptions and self-concept, because related empirical literature demonstrates that accurate academic self-concepts predict academic success. These results were extrapolated to a pharmacy clinical communications course where a lecture and laboratory series was designed to emphasize self-concept and facilitate communication skills improvement. The instructional design of this series promoted the advancement of students’ communication skills by using communication inventories, self-reflection activities, peer and class discussion, and lecture content. Class discussions, self-reflections, and baseline, and follow-up counseling activities throughout the semester provided evidence of improvements.

Keywords: communication, self-concept, self-esteem, curriculum

INTRODUCTION

In order to provide patient-centered care and promote optimal patient outcomes, pharmacists need to have effective interpersonal communication skills. Effective communication skills are not innate; they must be developed. For pharmacists, the development of these skills is often emphasized during pharmacy school in a clinical communication course where topics such as empathy, listening, nonverbal communication, assertiveness, and perception are covered.1 Perception is a particularly important topic in a communications course because our perceptions of others affect the way we communicate with them. Standard course content on perceptions emphasizes verbal and nonverbal messages communicated by others.

Coursework on perceptions should also include content on self-perception/self-concept because the way we communicate with others (our interpersonal skills) is also shaped by how we view ourselves.2 Having an accurate academic self-concept is a critical predictor of a student's academic success.3 Likewise, a student's awareness of his/her communication self-concept and ability to define himself/herself accurately relates to the ability to communicate with others successfully. Therefore, course content on perceptions should include emphasis on self-concept, because this focus should help students become more effective communicators. The self-concept content should focus on helping students reflect on their personal definitions of self, communication preferences, ability to articulate thoughts and needs, and overall communication strengths and weaknesses. Helping students realize that how they view themselves contributes to their communication ability is a primary and crucial step in the advancement of their skills.

A lecture and laboratory series on the importance of self-concept in advancing communication skills was created for a clinical communications course given to third-professional year doctor of pharmacy students on 2 campuses.

One goal of the lecture/laboratory series is to help students appreciate the role an accurate self-concept plays in their ability to communicate successfully in any situation. Thus, the context of the series is that of everyday life and their future roles as pharmacists.

A second goal is to help students understand how they define who they are (self-evaluation and evaluation by others) and the evolution and accuracy of their self-concept. Related to this goal, the series illustrates the relationship between self-concept and self-esteem, as well as how personal reflection and social comparison influence how people feel about the skills, knowledge, and attitude they possess.

The third goal is to relate the series content to previous lectures on perceptions and provide a foundation for future communication lectures designed to facilitate the advancement of clinical communication skills. This series on self-concept allows students to assess their perceived and actual communication abilities at the beginning of the semester. The baseline information facilitates students’ reliable and valid assessment of growth over the semester in the clinical communications course.

These goals translate into 12 total lecture and laboratory objectives (see modified list below). The lecture objectives focus on exploring the definitions, features, and development of a person's self-concept, as well as how self-esteem relates to self-concept, and the role self-esteem plays in effective communication. Once this foundation of knowledge is constructed, the laboratory objectives concentrate on students’ application, analysis, and evaluation of their self-concept through pre-assignment inventories and assessments and in-class active-learning exercises. The series content emphasizes the importance of self-evaluation and personal reflection, as well as how each student's definitions of self compare to those of his/her peers. The peer comparisons and discussions stress the role of social comparison and its relationship to self-esteem and self-concept.

Specific lecture and laboratory objectives require students to:

Define and evaluate your self-concept (general and communication);

Reflect on development and evolution of your own self-concept;

Analyze the accuracy of your self-concept;

Compare self-concept activity results through the lens of self-evaluation and evaluation by others;

Discuss and compare communication styles among your peers;

Contrast self-concept and self-esteem;

Evaluate fluctuations and influences on your own self-esteem; and

Utilize your self-concept to improve your ability to communicate effectively.

INSTRUCTIONAL METHODS AND CONTENT

Pre-assignment

This lecture/laboratory series within the required clinical communications course is offered during the first 3 weeks of the fall semester in the third-professional year. On the first day of class (week 1) students are given a pre-assignment (specific handout materials are available from author) that is due the following week (1 week prior to the lecture). The pre-assignment utilizes 4 activities that include taking (#1) an online communication inventory, the Keirsey Temperament Sorter II; 4 (#2-3) 2 paper-and-pencil inventories, the Interpersonal Communications Assessment (ICA),5 and the UZoo Communication and Leadership Inventory.6 Students also (#4) describe and illustrate their communication strengths and weaknesses and indicate their top strength and top weakness.7 After students complete these 4 required assignments, they compile their results on a score sheet and submit the materials. Once all pre-assignment materials are collected, student results for all of the inventories are tallied and class averages and minimum and maximum scores are calculated.

The self-concept and self-esteem content is delivered during week 2 of the course and is designed to capture students’ baseline communication strengths and weaknesses (handout materials and activities are available from the author). The 90-minute lecture emphasizes higher and lower levels of Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives. At the lower level, the lecture's objectives and content focus on knowledge accumulation with review of self-concept and self-esteem definitions, principles, origins, influences, and lifespan development. At the higher level, analysis and evaluation objectives are emphasized using class discussion and activities. Students self-reflect, analyze life experiences, describe their self-concept, determine the general level of their own self-esteem, and review personal and professional factors that contribute to their self-esteem. These activities are executed using personal introspection, peer discussion, and class discussion of personal thoughts and examples. These reflections are stimulated through class activities that ask students to develop a top 10 list of words that describe who they are and answer questions about how they and others see them (ie, I am skilled at, other people think that I am skilled at).2,8

The 2-hour laboratory session occurs during week 3. The class of approximately 140 students is divided into 4 sections of approximately 30 students each and the laboratory session is repeated for each section. The 2-hour period is divided into 4 segments: general, communication, personality, and leadership self-concept and self-esteem. Each segment requires approximately 30 minutes to complete (activity handout material is available from the author). The first segment, general self-concept review, uses activities that require students to reflect on how they define themselves overall, then to compare their reflections with a classmate, and then with the entire laboratory section. Students discuss and categorize their broad self-concept themes in 7 areas: skills, knowledge, personality and physical characteristics, social and professional roles, and belief systems.8 To conclude this section, the students are asked to decipher self-concept trends for the class based on the categorization of their self-concept lists.

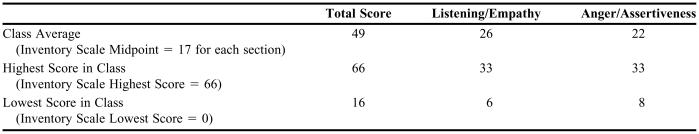

The second segment, communications self-concept, follows a similar format as the general self-concept segment, but the focus shifts to how students see themselves as communicators. The unique portion of this segment is the review of the Interpersonal Communications Assessment (ICA)5 that the students completed in the pre-assignment. This laboratory activity interprets the following 3 sections of the inventory: listening/empathy, anger/assertiveness, and total score. Students also receive feedback about how their results compare to average scores on the inventory and to class results (emphasizing social comparison and self-esteem). This allows students to more accurately self-reflect about their communication strengths and weaknesses, ie, self-concept building (see part A of laboratory handout in Appendix 1).

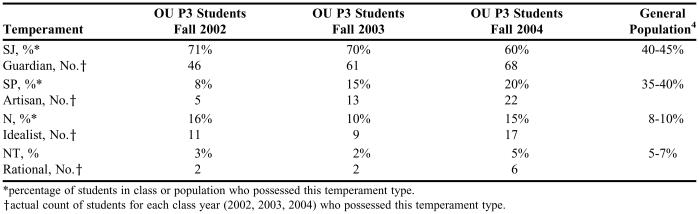

The personality segment (third segment) complements segment 2 and emphasizes the Keirsey Temperament Sorter II4 results achieved during the pre-assignment. This pre-assignment is available free online and relates to the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI).9 Since the cost and training required to offer the MBTI to this class is prohibitive, the Keirsey Temperament Sorter II is considered an acceptable alternative, although the validity and reliability of the online instrument are not well established. The goal of this portion of the course is to give students insight into their temperament and ability to “read” others. During this third segment, the class discusses the categories of the Keirsey Temperament Sorter II4,10 and the MBTI9 (artisan, guardian, idealist, and rational types). The students then reflect on their personal results and whether they feel the inventory accurately captures who they are. To emphasize the ability to read others, the class predicts each student's temperament type, followed by feedback provided by each student on the class's accuracy. This segment also uses data related to current and historical class percentages, as well as empirical results of the general population found in the literature4,10 to emphasize social comparison (see part B of Appendix 1).

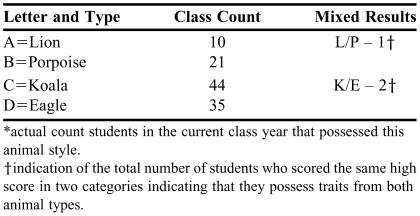

The fourth segment focuses on leadership and communication styles and addresses how students function on teams. This segment starts with a case activity that asks students to decide how to handle a dysfunctional team situation. Their approaches are compared to the UZoo Leadership and Communication Inventory6 pre-assignment results, which categorizes students as 1 of 4 animal types: lion, porpoise, koala, or eagle. The validity and reliability of the UZoo inventory has not been established, but the tool is used to stimulate student reflection, social comparison, and overall class discussion. To conclude this segment, the 4 categories of the inventory are reviewed and the class counts for each category (including mixed results where students scored the same high score in 2 categories indicating that they possess traits from both animal types) are revealed (see part C of Appendix 1). The laboratory ends with a summary of the 4 animal types and stresses the importance of accurately defining one's self-concept and practicing reading other students’ types in order to communicate effectively.

OUTCOMES

The self-concept session of the communications course has been offered for the past 5 years. Only 2 of the 5 years included the laboratory session due to scheduling conflicts. In the other 3 years, the pre-assignment was still utilized, the laboratory content was included in the class lecture, and handouts with social comparison data were provided to students for self-study purposes. This alteration to the series was not ideal because the small-group setting of the laboratory sections stimulated participation in group discussion, which facilitated student's personal reflection and peer comparison. In the laboratory's current design, the 2-hour time allotment is minimally sufficient to achieve the laboratory's objectives. In order to finish in 2 hours, pre-laboratory preparation and focus are needed. Effective management of students during the session with significant attention to time on task is also needed. Expanding the laboratory to 3 hours (15 additional minutes to review each of the 4 sections) may be more beneficial for addressing all 4 areas. If the laboratory time could not be expanded or there was only enough time to complete 2 segments of the laboratory, the UZoo inventory6 and the Interpersonal Communication Inventory5 appear to have the most impact on students. Therefore, students may benefit from altering the objectives to focus on these 2 of the 4 laboratory components.

There were 5 outcomes evaluated in the self-concept lecture and laboratory series. The first explored student completion rates of the inventories. All of the students in the course completed the pre-assignments for the lecture/laboratory series. This allowed for complete reporting of inventory results that were used for social comparison. A second outcome assessment that measured the series’ impact was measured using baseline and follow-up patient counseling videos completed at the beginning and end of the semester. Over the past 5 years, students demonstrated improvement on this assignment and this suggests the series offers a positive contribution to the advancement of students’ communication skills. However, these data are confounded by the other topics that are offered during the semester, since all course content probably has a positive impact. Isolating the exact content that enhanced students’ skills is difficult under the current design. Future offerings of the series need to include a deliberate measure of the impact of the self-concept content.

A third outcome of the series was that students participated well in the class and laboratory. This outcome was evidenced by their honest reflections in the writing exercises for their pre-assignment. The students were forthright during the explanations and illustrations of their communication strengths and weaknesses, with many comments focusing on significant relationship challenges they faced as a result of their communication weaknesses. The requirement to provide at least one specific personal example of a communication strength and weakness may have facilitated this honesty. This outcome was also evidenced verbally, where this honesty transferred into the laboratory series of the class where students avoided “socially acceptable” answers. Instead students reiterated pre-assignment sentiments, and as a result, some epiphany-like statements were made during the discussions that took place. The smaller and safer atmosphere of the laboratory sections may have encouraged this honesty. Overall, the students’ ability to honestly reflect and discuss their strengths and weaknesses is an important component in making improvements in the course.

Similarly, the fourth outcome of the series was that anecdotally, students reported enjoying the series. They informally report liking the discussions of the UZoo personality/leadership/communication styles inventory, which may relate to the use of teams throughout courses in the curriculum and the re-emphasis of UZoo concepts by faculty members in other courses. College faculty members have recognized the impact that the UZoo part of the series has on students during team-based exercises, but these are faculty members who also use the UZoo results in their classroom to reemphasize the importance of teaming, knowing yourself, and reading others well. Students have not made specific comments about the lecture and laboratory series in end-of-semester course evaluations; however, specific questions will be added to the course evaluations in future offerings of the course. This feedback will provide insight into the components that the students found most and least helpful so that appropriate emphasis and modifications can occur.

The final outcome was that the series affected future content in the communication course seen with assignments that documented students’ improvement in skills over the semester. The series also influenced other courses in the curriculum because results from the pre-assignment inventories were used to assist with selecting teams for class activities and to review team-building skills.

Overall, the course could benefit from fine-tuning the outcomes that were assessed during the series in order to capture the specific contribution that self-concept training has on communication skills improvement. It is possible that this could be achieved with precourse and postcourse skill testing and finding ways to reemphasize the series’ themes and measure their impact throughout the curriculum. In addition, since the course is currently given during the third-professional year, opportunities to reemphasize content, hold students accountable for learning, and measure retention of course content are limited. The course itself may benefit from movement to the first year of the program so these concepts can be introduced earlier, become more embedded in the curriculum, and to allow students more time to practice these skills.

SUMMARY

The teaching of self-concept is important in a clinical communications course because perceptions of others and self have an important role in interpersonal communication. Asking students to reflect on and articulate who they are as individuals and future professionals provides a foundation for making improvements in their ability to effectively communicate with others. Improving communication ability is vital in pharmacy students preparing to enter professional practice, which increasingly requires refined interpersonal communication skills. Introspection is one of the first steps in this journey.

Appendix 1. Laboratory Handout of Inventory Results Used for Social Comparison

Part A. Results of Interpersonal Communication Assessment5 for Current Class-Compared to the Inventory Scale

Part B. Results of Keirsey Temperament Sorter4,10 for the Current Class, Compared to Previous Pharmacy Student Classes, the General Population, and General Pharmacy Students

*percentage of students in class or population who possessed this temperament type.

†actual count of students for each class year (2002, 2003, 2004) who possessed this temperament type.

Part C. UZoo6 Type Results for Current Class

*actual count students in the current class year that possessed this animal style.

†indication of the total number of students who scored the same high score in two categories indicating that they possess traits from both animal types.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tindall WN, Beardsley RS, Kimberlin CL. Communication Skills in Pharmacy Practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verderber KS, Verderber RF. Inter-act: Interpersonal Communication Concepts, Skills, and Context. 9th ed. Canada: Wadsworth; 2001. pp. 42–69. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouchey HA, Harter S. Reflected appraisals, academic self-perceptions, and math/science performance during early adolescence. J Educ Psychol. 2005;97:673–86. [Google Scholar]

- 4. The Keirsey Temperament Sorter II. Available at: http://www.keirsey.com/cgi-bin/keirsey/newkts.cgi. Accessed August 15, 2005.

- 5.Bienvenu MJ. An interpersonal communication inventory. J Commun. 1971;21:381–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eckstein K. University of Oklahoma Student Services; 2002.. The UZoo Leadership and Communication Inventory [unpublished assessment tool] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zinner-Dolphin C, Adler RB, Rosenfeld LB, Towne N, Proctor RF., III . Forth Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace; 1998. Instructor's manual/test bank: Interplay: The Process of Interpersonal Communication; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adler RB, Rosenfeld LB, Towne N, Proctor RF., III . Interplay: The Process of Interpersonal Communication. 7th edition. Forth Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace; 1998. pp. 72–131. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myers K, Kirby L. Introduction to Type, Dynamics and Development. Palo Alto, Calif: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berens LV. Understanding Yourself and Others: An Introduction to Temperament. Huntington Beach, Calif: Telos Publications; 1998. pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]