Abstract

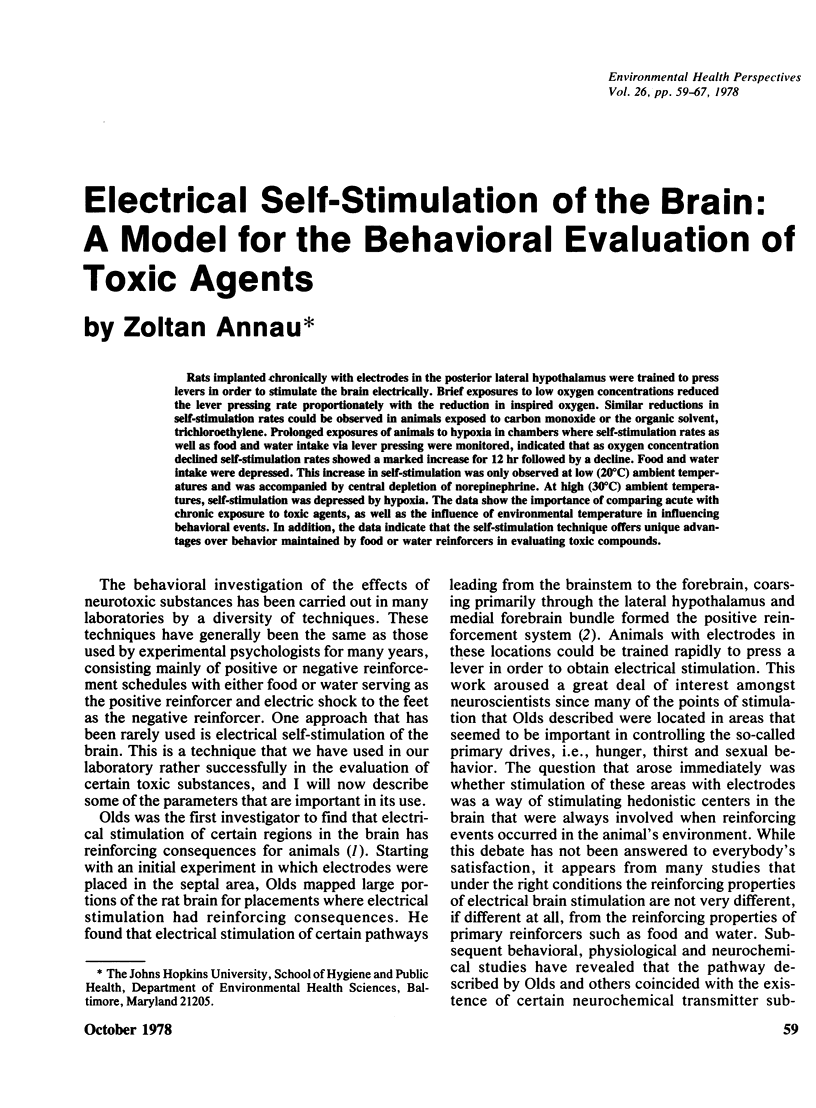

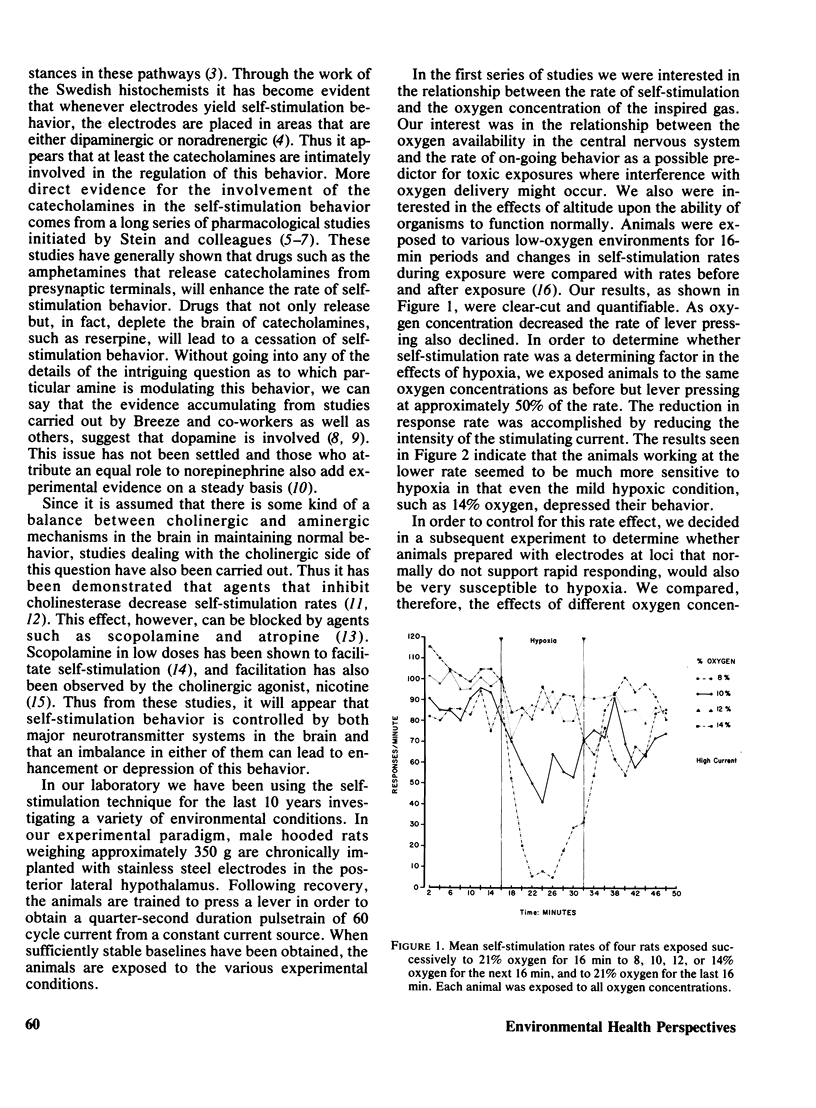

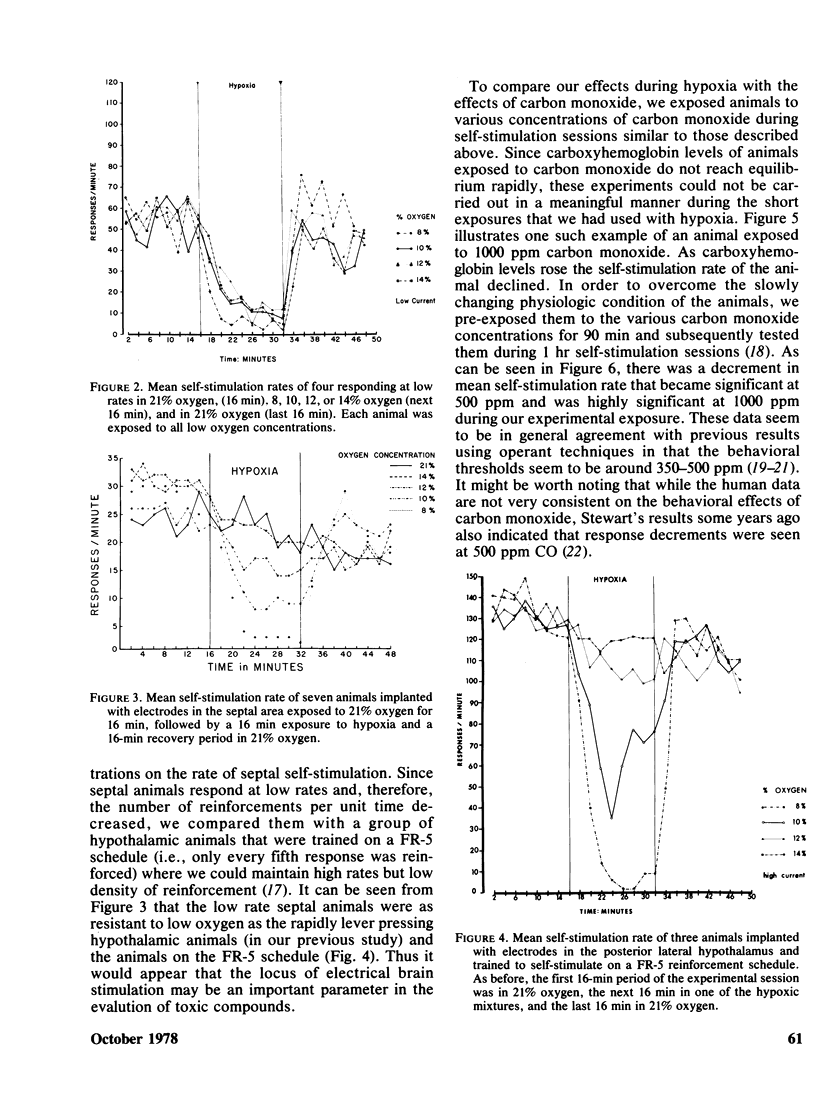

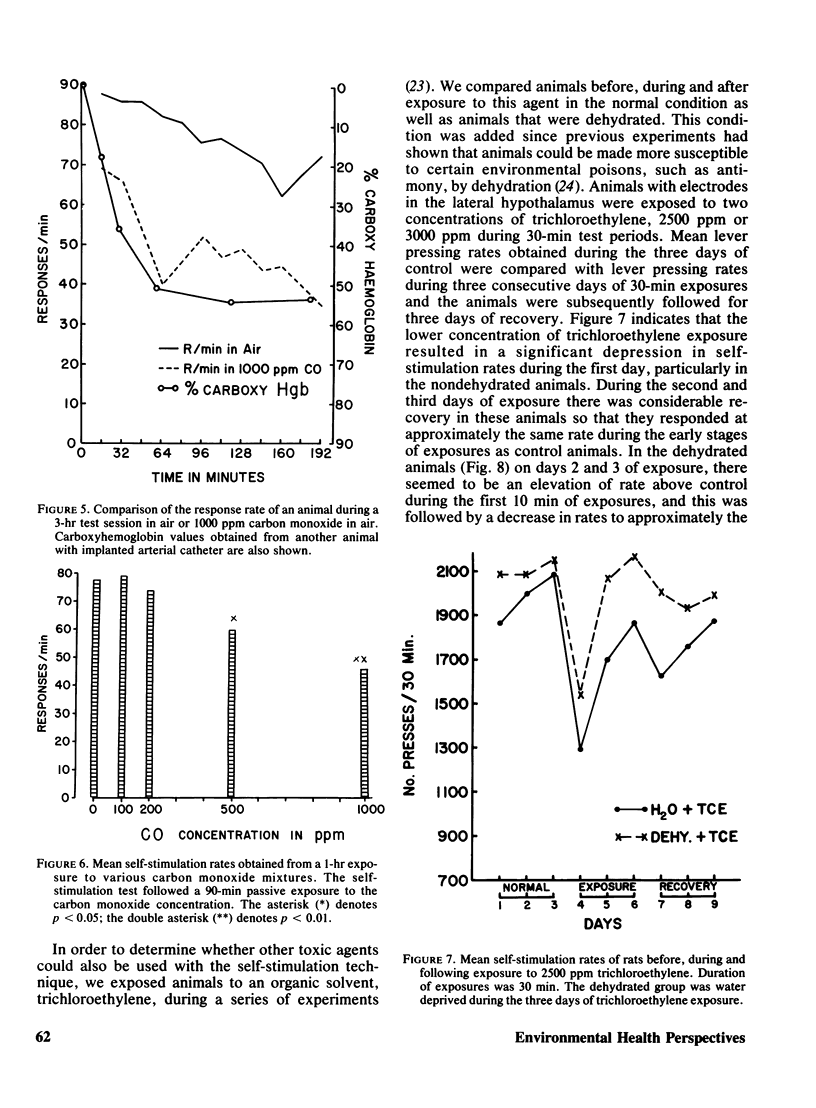

Rats implanted chronically with electrodes in the posterior lateral hypothalamus were trained to press levers in order to stimulate the brain electrically. Brief exposures to low oxygen concentrations reduced the lever pressing rate proportionately with the reduction in inspired oxygen. Similar reductions in self-stimulation rates could be observed in animals exposed to carbon monoxide or the organic solvent, trichloroethylene. Prolonged exposures of animals to hypoxia in chambers where self-stimulation rates as well as food and water intake via lever pressing were monitored, indicated that as oxygen concentration declined self-stimulation rates showed a marked increase for 12 hr followed by a decline. Food and water intake were depressed. This increase in self-stimulation was only observed at low (20 degrees C) ambient temperatures and was accompanied by central depletion of norepinephine. At high (30 degrees C) ambient temperatures, self-stimulation was depressed by hypoxia. The data show the importance of comparing acute with chronic exposure to toxic agents, as well as the influence of environmental temperature in influencing behavioral events. In addition, the data indicate that the self-stimulation technique offers unique advantages over behavior maintained by food or water reinforcers in evaluating toxic compounds.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Annau Z. Comparison of septal and hypothalamic self-stimulation during hypoxia. Physiol Behav. 1977 Apr;18(4):735–737. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(77)90075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annau Z., Heffner R., Koob G. F. Electrical self-stimulation of single and multiple loci: long term observations. Physiol Behav. 1974 Aug;13(2):281–290. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(74)90046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annau Z., Weinstein S. A. Hypothalamic self-stimulation: interaction of hypoxia and stimulus intensity. Life Sci. 1967 Jul 1;6(13):1355–1360. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(67)90181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baetjer A. M., Annau Z., Abbey H. Water deprivation and trichloroethylene. Effect on hypothalamic self-stimulation. Arch Environ Health. 1970 Jun;20(6):712–719. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1970.10665648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baetjer A. M. Effects of dehydration and environmental temperature on antimony toxicity. Arch Environ Health. 1969 Dec;19(6):784–792. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1969.10666931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domino E. F., Olds M. E. Cholinergic inhibition of self-stimulation behavior. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1968 Nov;164(1):202–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German D. C., Bowden D. M. Catecholamine systems as the neural substrate for intracranial self-stimulation: a hypothesis. Brain Res. 1974 Jun 28;73(3):381–419. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90666-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung O. H., Boyd E. S. Effects of cholinergic drugs on self-stimulation response rates in rats. Am J Physiol. 1966 Mar;210(3):432–434. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1966.210.3.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan D. E., Miller A. T., Jr Interactions between carbon monoxide and d-amphetamine or pentobarbital on schedule-controlled behavior. Environ Res. 1974 Aug;8(1):53–63. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(74)90062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merigan W. H., McIntire R. W. Effects of carbon monoxide on responding under a progressive ratio schedule in rats. Physiol Behav. 1976 Apr;16(4):407–412. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(76)90318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLDS J., MILNER P. Positive reinforcement produced by electrical stimulation of septal area and other regions of rat brain. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1954 Dec;47(6):419–427. doi: 10.1037/h0058775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds M. E., Domino E. F. Comparison of muscarinic and nicotinic cholinergic agonists on self-stimulation behavior. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1969 Apr;166(2):189–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan S. N., Bowling C. Effects of nicotine on self-stimulation in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1971 Jan;176(1):229–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEIN L. SELF-STIMULATION OF THE BRAIN AND THE CENTRAL STIMULANT ACTION OF AMPHETAMINE. Fed Proc. 1964 Jul-Aug;23:836–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein L., Belluzzi J. D., Ritter S., Wise C. D. Self-stimulation reward pathways: norepinephrine vs dopamine. J Psychiatr Res. 1974;11:115–124. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(74)90082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein L., Wise C. D. Release of norepinephrine from hypothalamus and amygdala by rewarding medial forebrain bundle stimulation and amphetamine. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1969 Feb;67(2):189–198. doi: 10.1037/h0026767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart R. D., Newton P. E., Hosko M. J., Peterson J. E. Effect of carbon monoxide on time perception. Arch Environ Health. 1973 Sep;27(3):155–160. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1973.10666345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerstedt U. Stereotaxic mapping of the monoamine pathways in the rat brain. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1971;367:1–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201x.1971.tb10998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]