Abstract

Spindle disruption or DNA damage prevents sister chromatid separation through the activation of checkpoint pathways that inhibit anaphase entry by stabilizing the anaphase inhibitor Pds1. Mutation of CDC55, which encodes a B regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), results in precocious sister chromatid separation when spindle is disrupted. Here we report that decreased Pds1 levels in Δcdc55 mutants contribute to sister chromatid separation in the presence of nocodazole, a microtubule-depolymerizing drug. However, in the presence of DNA damage, Δcdc55 mutant cells separate sister chromatids without noticeable decrease of Pds1 or cohesin Mcd1/Scc1 levels. Further analysis demonstrates that Δcdc55 mutants lose cohesion along the entire chromosomes when the spindle is disrupted. In contrast, separation of sister chromatids is limited to the centromeric regions in Δcdc55 cells after DNA damage. Moreover, mutation of TPD3, which encodes the A regulatory subunit of PP2A, also results in sister chromatid separation in DNA- or spindle-damage-arrested cells. These data suggest that PP2A regulates sister chromatid cohesion in Pds1-dependent and -independent manners.

Keywords: Cdc55, checkpoint, Tpd3

Chromosome separation is a key step in the cell cycle. After DNA duplication and proper alignment of chromosomes at the spindle equator, cohesion, the molecular glue that holds sister chromatids together, is dissolved through separase-dependent cleavage. Sister chromatids then are pulled apart by spindle microtubules emanating from opposite poles and segregated into the two daughter cells such that each cell receives one set of the chromosomes. The cohesin that forms a ring around sister chromatids is a protein complex consisting of several subunits (1, 2). In yeast, dissolution of cohesion at the metaphase-to-anaphase transition is achieved by separase (Esp1)-triggered cleavage of one subunit, Mcd1/Scc1 (3). Separase Esp1 is kept inactive during most of the cell cycle by inhibitory binding of securin Pds1 (4). Shortly before anaphase, Pds1 is destroyed by the E3 ubiquitin ligase anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) (5), leading to the activation of separase Esp1. Thus, the destruction of Pds1 and the subsequent cleavage of cohesion by released Esp1 are believed to be essential for anaphase onset (3, 6).

Separation of sister chromatids is tightly regulated during cell cycle. Cells have evolved surveillance mechanisms (called checkpoints) to ensure that sister chromatid segregation occurs only when all of the chromosomes have properly attached to the mitotic spindle. Common intracellular damages, such as DNA and spindle damage, activate checkpoint responses that lead to a preanaphase arrest (7–9). Stabilization of the APC/C substrate Pds1 has been shown to contribute to the arrest in both checkpoint pathways, although the mechanisms by which cells maintain the Pds1 abundance differ. Inhibition of APC/C activity accounts for the accumulation of Pds1 in the presence of spindle damage (10), whereas phosphorylation of Pds1 by Chk1 kinase after DNA damage renders Pds1 resistant to APC/C destruction (11, 12).

Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) is a conserved serine/threonine protein phosphatase involved in multiple cellular functions, including cell-cycle regulation, cell morphology, as well as various cellular signal transductions (13). This holoenzyme consists of a catalytic subunit, C, and two regulatory subunits, A and B. In budding yeast, PPH21, PPH22, and PPH3 genes encode the catalytic subunits (14). TPD3 encodes the A regulatory subunit, whereas CDC55 and RTS1 encode the B and B′ regulatory subunits, respectively (15, 16). We and others found that PP2A plays a negative role in mitotic exit, a process that inactivates cyclin-dependent kinase (17, 18). PP2A may regulate mitotic exit by dephosphorylating Net1, a protein that sequesters Cdc14 phosphatase within the nucleolus (19). Recent studies also have uncovered that PP2A forms a complex with SgoI to protect centromeric cohesion in yeast meiosis as well as in human mitosis (20–22). Additionally, PP2A has been implicated in the spindle-assembly checkpoint (23, 24), as indicated by the sensitivity of PP2A mutant cells to spindle-depolymerizing drugs such as nocodazole and benomyl. In the absence of Cdc55, the B regulatory subunit of PP2A, cells are unable to arrest in metaphase after nocodazole treatment and display precocious sister chromatid separation (23).

To better understand the regulation of anaphase entry, we sought to investigate the molecular mechanism underlying the precocious sister chromatid separation of Δcdc55 mutants in nocodazole. Our data showed that Δcdc55 cells failed to maintain Pds1 levels and exhibited cleavage of Mcd1 in the presence of spindle poison, suggesting that degradation of Pds1 and the subsequent liberation of separase Esp1 might be responsible for the precocious sister chromatid separation. Surprisingly, overexpression of nondegradable Pds1 or inactivation of separase Esp1 failed to suppress the sister separation completely in Δcdc55 mutants, indicating that Cdc55 also may regulate sister separation in a Pds1-independent manner. Mutation of CDC13 induces DNA lesions in the telomeric regions that activate DNA damage checkpoint and arrest cells before anaphase (25, 26). The cdc13–1 Δcdc55 cells maintained the Pds1 level but nevertheless displayed separated sisters when grown at the restrictive temperature. Furthermore, in contrast to the nocodazole-treated Δcdc55 cells that show sister chromatid separation along the lengths of chromosome, the separation of sister chromatids in cdc13–1 Δcdc55 mutants takes place preferentially in centromeric regions.

Resultss

Δcdc55 Mutants Exhibit Precocious Sister Chromatid Separation in the Presence of Spindle Damage.

Previous studies suggest that Cdc55, the B type regulatory subunit of PP2A in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is required to prevent sister chromatid separation when spindle–kinetochore interaction fails (23, 24). However, it remains unclear what defects in Δcdc55 mutants cause the premature sister chromatid separation. To address this issue, we first reexamined the sister separation in WT and Δcdc55 cells treated with nocodazole, a microtubule-depolymerizing drug, by visualizing a GFP-marked chromosome at the URA3 locus, 35 kb from the centromere of chromosome V (2). After the release from a G1 arrest into medium containing 20 μg/ml nocodazole, >95% of the WT cells collected at different time points exhibited a single GFP dot. The Δcdc55 cells in contrast displayed an increasing frequency of sister chromatid separation as cell cycle proceeded, with 54% of the cells containing two GFP dots 3 h after the release (Fig. 1A), supporting the notion that sister chromatids are precociously separated in the absence of Cdc55 after spindle damage (23).

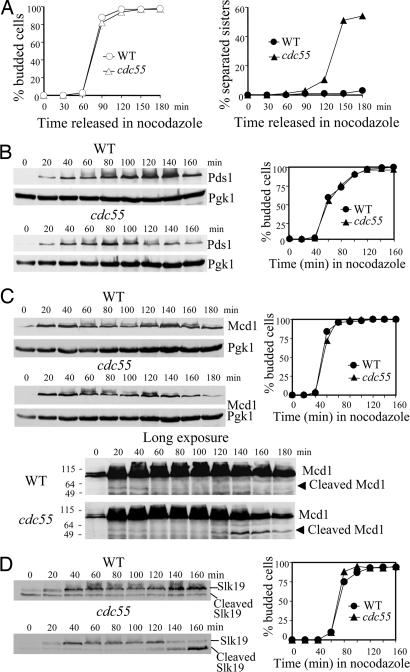

Fig. 1.

Degradation of Pds1 contributes to the precocious sister chromatid separation in Δcdc55 mutants after spindle damage. (A) Δcdc55 mutants inappropriately entered anaphase in the presence of nocodazole. WT and Δcdc55 strains, each carrying a GFP-fusion at the URA3 locus, were arrested at G1 phase with α-factor, released into medium containing 20 μg/ml nocodazole, and withdrawn to visualize partitioning of URA3-GFP. Cell-budding index and the kinetics of URA3-GFP separation are shown. (B) Nocodazole-treated Δcdc55 cells exhibit decreased Pds1 levels. WT and Δcdc55 cells expressing PDS1-Myc18 were synchronized at G1 phase, released into medium containing 20 μg/ml nocodazole, and collected every 20 min to prepare protein extracts for Western blotting. Pds1 protein levels and the cell-budding profile are shown. Pgk1 protein levels were used as loading control. (C) Δcdc55 mutants exhibit decreased Mcd1 levels in the presence of nocodazole. WT and Δcdc55 cells expressing MCD1-HA6 were treated as described in B for immunoblotting analysis. The cleaved products of Mcd1 were detected after long exposure (Bottom). (Right) The budding index is shown. (D) Slk19 protein level drops in Δcdc55 mutants in the presence of nocodazole. WT and Δcdc55 cells expressing SLK19-HA6 were treated as described in B. Full-length Slk19 and cleaved Slk19 products (Left) and budding index (Right) are shown.

Degradation of Pds1 May Cause the Anaphase Entry in Δcdc55 Mutants After Spindle Damage.

Upon activation of the spindle-assembly checkpoint, anaphase inhibitor Pds1 is stabilized and maintained at high abundance to prevent anaphase entry (10). The precocious sister chromatid separation in Δcdc55 mutants suggests that the cells inappropriately enter anaphase in the presence of disrupted spindles. We examined the accumulation of Pds1 in nocodazole-treated WT and Δcdc55 mutant cells. As expected, WT cells maintained Pds1 at high levels after being released into medium containing nocodazole. Δcdc55 mutant cells, however, demonstrated a drop of Pds1 level 100 min after release (Fig. 1B). Results from the Burke laboratory (18) also indicate decreased Pds1 protein levels in nocodazole-treated Δcdc55 cells.

Pds1 inhibits the onset of anaphase by binding to separase Esp1, whose activity is required for the cleavage of cohesin Mcd1. Given the decreased Pds1 protein levels, one would predict that Esp1 might be activated in nocodazole-treated Δcdc55 cells, which in turn leads to cleavage of Mcd1 and sister chromatid separation. To test this possibility, we examined Mcd1 protein levels in WT and Δcdc55 strains. As shown in Fig. 1C, Δcdc55 cells failed to maintain the abundance of intact Mcd1 and accumulated cleaved Mcd1 products in the presence of nocodazole, whereas Mcd1 remained abundant and no Mcd1 cleavage products were detected in WT cells. Similarly, cleavage of Slk19, another substrate of Esp1 (27), also was detected in Δcdc55 cell extracts, as judged by the decrease of full-length Slk19 and the increase of cleaved Slk19 products (Fig. 1D). These results suggest that activation of separase Esp1 contributes to the anaphase entry in Δcdc55 mutants in the presence of nocodazole, presumably because of the degradation of anaphase inhibitor Pds1.

Inactivation of APC/C Suppresses the Sister Chromatid Separation in Nocodazole-Treated Δcdc55 Cells.

We observed obvious decrease of cohesin Mcd1 protein level in Δcdc55 cells treated with nocodazole, concomitantly with decreases in Pds1 protein levels. Degradation of Pds1 depends on the activity of APC/C ubiquitin ligase, acting in conjunction with its activator, Cdc20 (5, 28). Thus, the failure of Δcdc55 cells to arrest in metaphase might be attributable to hyperactive APC/C. To test this idea, we introduced a temperature-sensitive mutant of CDC20, cdc20–1, to Δcdc55 and examined the sister chromatid separation after incubation in the presence of nocodazole at 37°C for 3 h. Approximately 5% of cdc20–1 single mutant cells and 22% of Δcdc55 cdc20–1 cells exhibited two GFP dots, in comparison with 54% separation in Δcdc55 mutants (Fig. 1A). We noticed that Δcdc55 cdc20–1 mutants showed higher frequency of separation than the cdc20–1 single mutant did, presumably because of the Pds1-independent sister chromatid separation at centromeric regions, which will be discussed later. This result suggests that inactivation of Cdc20 and thus blocking the APC/C activity suppresses the precocious sister chromatid separation in Δcdc55 cells after spindle disruption.

Δcdc55 Cells also Exhibit Sister Chromatid Separation in the Presence of Stabilized Pds1.

Because we observed a drop of Pds1 level in Δcdc55 mutants that exhibited separated sister chromatids in the presence of spindle damage, we reasoned that the separation should be suppressed by high dosage of Pds1 protein. Thus, we overexpressed the nondegradable form of Pds1 (Pds1Δdb) (5) in Δcdc55 mutants and examined the sister chromatid separation. Δcdc55 and the WT cells harboring the PGAL-PDS1-Δdb plasmid were incubated in medium containing raffinose until mid-log phase and then transferred to synthetic medium containing galactose to induce Pds1-Δdb. WT cells displayed no increase in the frequency of URA3-GFP partitioning, consistent with the notion that Pds1-Δdb inhibits the onset of anaphase (5). Interestingly, Δcdc55 mutants still accumulated cells displaying two GFP dots when Pds1-Δdb was induced (Fig. 2A). In contrast, sister chromatid separation in mad2 cells, defective for spindle-assembly checkpoint, could be suppressed by the overexpression of PDS1-Δdb, indicating additional functions of PP2A.

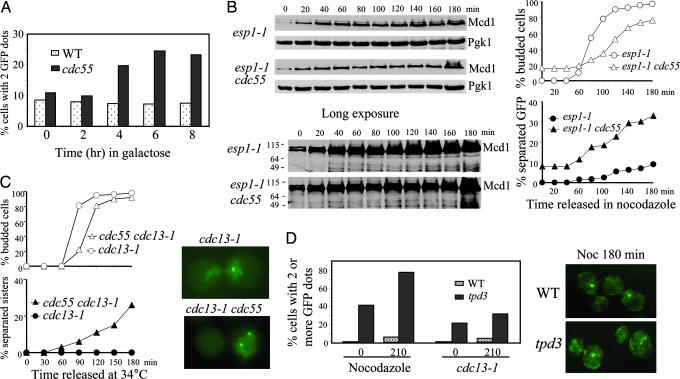

Fig. 2.

Δcdc55 cells exhibit precocious sister chromatid separation in the presence of Pds1. (A) Overexpression of Pds1 fails to suppress the premature separation of sister chromatids in Δcdc55 mutants. WT and Δcdc55 mutant cells carrying PGAL-PDS1-ΔDB were incubated in the presence of galactose and then collected every 2 h to examine sister chromatid separation. The percentage of cells with two or more GFP dots is shown. (B) Δcdc55 mutants exhibit separated sister chromatids when Esp1 is inactive. G1-arrested cells of esp1–1 and Δcdc55 esp1–1 carrying GFP-marked chromosome V and HA-tagged Mcd1 were released into YPD medium containing 20 μg/ml nocodazole and incubated at 37.5°C. The kinetics of sister chromosome separation and Mcd1 accumulation are shown. (C) Precocious sister chromatid separation in cdc13–1 Δcdc55. G1 cells of cdc13–1 and cdc13–1 Δcdc55 carrying URA3-GFP were released at 34°C. The cell-budding profile (Upper Left), kinetics of sister chromatid separation (Lower Left), and micrographs of cells with GFP dots (Right) are shown. (D) Nocodazole and cdc13–1-arrested Δtpd3 mutant cells display separated sister chromatids. WT and Δtpd3 mutant cells carrying URA3-GFP were synchronized at G1 and then released into medium containing 20 μg/ml nocodazole. Cells were collected at the indicated times to examine sister chromatid separation. Similar experiment was repeated with cdc13–1 and cdc13–1 Δtpd3 mutants released into YPD medium at 34°C. Percentages of cells with multiple GFP dots (Left) and fluorescence micrographs of cells incubated in nocodazole for 180 min (Right) are shown.

If a Pds1 degradation-independent mechanism contributes partially to the sister chromatid separation in Δcdc55 mutants, separase Esp1 might be dispensable for this process. Thus, we introduced esp1–1 into Δcdc55 strain and examined the separation of URA3-GFP and Mcd1 protein levels. Inactivation of Esp1 failed to suppress the sister chromatid separation in Δcdc55 mutants completely. Separated GFP dots were detected in 33% of the esp1–1 Δcdc55 cells after being released into nocodazole at 37.5°C for 3 h from the G1 arrest vs. 9% in the esp1–1 single mutants (Fig. 2B Right). Western blotting analysis of Mcd1 confirmed that the esp1–1 Δcdc55 mutants maintained the Mcd1 levels and exhibited no Mcd1 cleavage (Fig. 2B), excluding the possibility that Mcd1 cleavage is responsible for the chromosome separation in esp1–1 Δcdc55. These observations support the existence of a Pds1/Esp1-independent sister chromatid separation in Δcdc55 mutants.

Δcdc55 Cells Exhibit Sister Chromatid Separation in the Presence of DNA Damage.

Presence of DNA damage is known to activate DNA damage checkpoint that causes accumulation of phosphorylated Pds1 resistant to APC/C destruction (11, 12). To further confirm that Δcdc55 cells can dissociate sister chromatids in the presence of Pds1, we examined the sister chromatid separation in cdc13–1 Δcdc55 mutants. Loss of CDC13 function induces DNA lesions in the telomere proximal regions and causes cells to arrest before anaphase (25, 26). The cdc13–1 and cdc13–1 Δcdc55 cells growing at 25°C were first arrested in G1 phase and then released into fresh medium at 34°C, the nonpermissive temperature for cdc13–1. After the release, both cdc13–1 and cdc13–1 Δcdc55 cells gradually were arrested as large-budded cells, with slower kinetics observed for cdc13–1 Δcdc55. Examination of GFP signals located at the URA3 locus revealed almost no separation of sister chromatids in the cdc13–1 single mutant, suggestive of a preanaphase arrest. In contrast, cells displaying two GFP dots were frequently detected in cdc13–1 Δcdc55 double mutants. Approximately 25% of the cdc13–1 Δcdc55 cells showed two GFP dots 3 h after release at 34°C (Fig. 2C), indicating a failure to prevent sister chromatid separation in the absence of Cdc55 after DNA damage.

The A Regulatory Subunit of PP2A, Tpd3, also Is Required for the Preanaphase Arrest.

PP2A consists of three subunits (16, 29). We have shown that the budding yeast B regulatory subunit Cdc55 is required to maintain sister chromatid cohesion in the presence of DNA damage and spindle disruption. To see whether other subunits of PP2A also are required for sister chromatid cohesion, we examined chromosome separation in mutants defective for the A regulatory subunit Tpd3. As shown in Fig. 2D, after treatment with nocodazole or inactivation of cdc13–1, Δtpd3 cells exhibited an increased frequency of sister separation. Remarkably, we observed a significant portion (42%) of G1-arrested Δtpd3 cells containing more than one GFP dot, presumably as a consequence of uneven chromosome segregation in previous mitosis. The percentage of cells displaying multiple GFP dots increased to 78% after the culture was released into 20 μg/ml nocodazole for 210 min. Like Δcdc55, the Δtpd3 mutants exhibited less frequent sister chromatid separation after DNA damage than after nocodazole treatment. After incubation at 34°C for 210 min, the cdc13–1 Δtpd3 cells showing two or more GFP dots increased from 20% to 32% (Fig. 2D). It appeared, however, that the Δtpd3 cells were more prone to become multiploid even in unperturbed cell cycles, indicating a more severe defect of Δtpd3 than Δcdc55. Consistently, Δtpd3 cells were found to grow poorly even on rich yeast extract/peptone/dextrose (YPD) plates. We found that the Δtpd3 mutants were sensitive to benomyl, another drug that depolymerizes microtubules (data not shown). Because we have previously demonstrated that the catalytic subunit mutant Δpph21 Δpph22 also was sensitive to benomyl (17), it is very likely that the holoenzyme of PP2A is required for preventing sister chromatid separation in the presence of nocodazole.

Cdc55 Regulates Sister Chromatid Separation Independently of Pds1 After DNA Damage.

It appears that Cdc55 regulates sister chromatid separation in Pds1-dependent and -independent manners. It is not clear whether the lack of Cdc55 overrides the DNA damage checkpoint by down-regulating Pds1 protein levels. Therefore, we examined Pds1 protein levels in cdc13–1 and cdc13–1 Δcdc55 strains. In agreement with previous reports (11, 12), Pds1 was stabilized in cdc13–1 mutants incubated at the restrictive temperature. Strikingly, Pds1 also was stabilized in cdc13–1 Δcdc55 mutants (Fig. 3A), where cells separated their sister chromatids. We then monitored the cleavage of Mcd1 in cdc13–1 and cdc13–1 Δcdc55 cells. The cdc13–1 Δcdc55 mutant cells maintained the abundance of Mcd1 at levels comparable to the cdc13–1 single mutant (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that the sister chromatid separation in Δcdc55 mutants after DNA damage is independent of Pds1 regulation.

Fig. 3.

Cdc55 regulates sister chromatid segregation independently of Pds1 in response to DNA damage. (A) Pds1 is stabilized in cdc13–1 Δcdc55 mutants. G1-arrested cells of cdc13–1 PDS1-Myc18 and cdc13–1 Δcdc55 PDS1-Myc18 were released into YPD medium at 34°C. Crude protein extracts were prepared for Western blotting analysis. Cell-budding profile is shown in Right. (B) Mcd1 protein level is persistent in Δcdc55 mutants in the presence of DNA damage. G1 cells of cdc13–1 MCD1-HA6 and cdc13–1 Δcdc55 MCD1-HA6 were released at 34°C and withdrawn to prepare protein extracts for immunoblotting of Mcd1-HA6. The budding index is shown in Right.

Taken together, we conclude that in the presence of spindle or DNA damage, Cdc55 is required for sister chromatid cohesion via Pds1-dependent and -independent mechanisms. If this is the case, introduction of the CDC55 deletion into a Δpds1 mutant may exacerbate the defects in sister chromatid cohesion. We crossed Δcdc55 and Δpds1 mutants to obtain Δcdc55 Δpds1 double mutants. However, no viable double mutant cells were obtained after we dissected ≈30 tetrads, indicating that Δcdc55 and Δpds1 are synthetically lethal. This phenotype lends support to the existence of Pds1-independent regulation of sister chromatid separation by Cdc55. The lethality of Δcdc55 and Δpds1 double mutant may stem from the catastrophic mitosis caused by the absence of both Cdc55 and Pds1.

Sister Chromatid Cohesion at Centromere and Telomere Proximal Regions in Δcdc55 Mutants.

Pds1-independent sister chromatid separation has been reported in smt4 mutants. Smt4 is a SUMO-1 isopeptidase that regulates sister chromatid cohesion through modification of topoisomerase II and Pds5 (30, 31). Interestingly, smt4 mutants exhibit separated sister chromatids at centromeric but not in telomeric regions when arrested with DNA damage. The cohesion loss in smt4 mutants cannot be suppressed by overexpression of nondegradable Pds1. Given the similarity between smt4 and Δcdc55, it is possible that the sister chromatid separation in Δcdc55 mutants also is limited to centromeric regions after DNA damage.

To examine sister chromatid cohesion along the chromosome, we first compared the separation of GFP-marked sequences at different regions of chromosome in Δcdc55 cells after nocodazole treatment. The tetO arrays were integrated 2 kb away from the centromere of chromosome IV (Cen-GFP) or 30 kb away from the telomere of chromosome V (Tel-GFP) in Δcdc55 mutants (Fig. 4A) (32). After being released into medium containing 20 μg/ml nocodazole for 3 h from G1 arrest, Δcdc55 cells exhibited similar frequencies of sister separation in the centromeric (60.1%) and telomeric (57.2%) regions (Fig. 4B). It is therefore likely that the decreased Pds1 protein level in Δcdc55 cells results in cleavage of cohesin along the entire chromosomes in the presence of nocodazole.

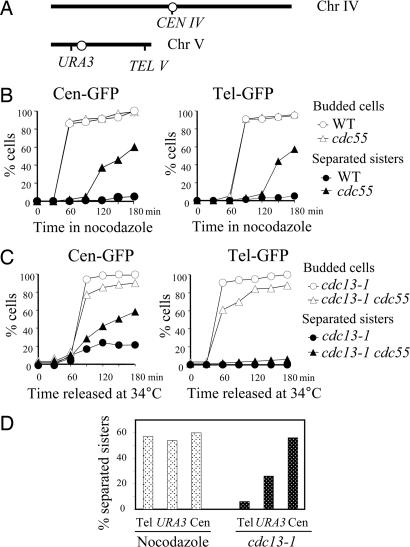

Fig. 4.

Sister chromatid separation in Δcdc55 mutants at different loci along the chromosomes after spindle or DNA damage. (A) Diagram showing the location of TetO arrays in chromosome IV and V. (B) Sister chromatid separation in Δcdc55 mutants at centromere and telomere in the presence of nocodazole. WT and Δcdc55 cells carrying tetO arrays at centromere or telomere were arrested in G1 phase and then released into nocodazole (20 μg/ml) medium at 30°C. (Left) Kinetics of Cen-GFP separation and the budding index. (Right) Kinetics of Tel-GFP separation and the budding index. (C) Centromeric and telomeric sister chromatid separation in cdc13–1-arrested Δcdc55 mutants. cdc13–1 and cdc13–1 Δcdc55 mutant cells carrying tetO arrays at centromere, as well as those carrying the tetO arrays at telomere, were first arrested in G1 phase at 25°C and then released at 34°C. The budding index and the percentage of cells with separated GFP dots are shown. (D) Comparison of sister chromatid separation rates at telomere, the URA3 locus, and centromere in Δcdc55 cells arrested by nocodazole and DNA damage. Δcdc55 (Left) and cdc13–1 Δcdc55 (Right) carrying tetO arrays at different loci were treated as described in A and B. Shown are percentages of GFP-dot separation in cells collected 180 min after release.

We then examined the sister chromatid separation in centromeric and telomeric regions in cdc13–1 Δcdc55 mutant cells. After the G1-arrested cells were released at 34°C for 3 h, 20% of cdc13–1 single mutant cells exhibited separated GFP dots that marked the centromeric region, presumably because of the transient sister separation at the centromere (33, 34). In cdc13–1 Δcdc55 mutants, ≈60% of the cells exhibited separated Cen-GFP (Fig. 4C). Notably, however, when examined at telomeres, the extent of sister separation in cdc13–1 Δcdc55 was greatly reduced. Only 8% of the cdc13–1 Δcdc55 cells showed separated GFP dots located at the telomere of chromosome V after release for 3 h (Fig. 4C), suggesting that Cdc55 is not required for maintaining sister chromatid cohesion at the telomeric regions in response to DNA damage.

We compared the sister separation frequencies in Δcdc55 mutants at centromere, telomere, as well as the URA3 loci in response to spindle and DNA damage. In response to spindle depolymerization, Δcdc55 cells showed similar separation frequencies at different loci along the chromosome (from 54% to 60%) (Fig. 4D). In contrast, the separation rates varied dramatically in different regions in cdc13–1 Δcdc55 mutants after DNA damage. We observed 8%, 25%, and 60% of cdc13–1 Δcdc55 cells showing separated sisters at the telomere, URA3 locus, and centromere, respectively (Fig. 4D), indicating a centromere specific cohesion defect in Δcdc55 cells in the presence of DNA damage.

Discussion

Here we describe that PP2A regulates sister chromatid separation by two distinct mechanisms. In the presence of spindle disruption, Δcdc55 mutants fail to keep high levels of Pds1, the anaphase inhibitor in budding yeast. As a result, the cohesin Mcd1 is cleaved by separase Esp1, resulting in precocious chromosome separation. In addition, Δcdc55 cells also display precocious sister chromatid separation in the presence of DNA damage. However, this separation differs from that observed in Δcdc55 cells after spindle disruption. First, the separation is limited to centromeric regions. Second, the separation is not accompanied by degradation of Pds1 or cleavage of cohesin Mcd1. Thus, a failure to establish or maintain centromeric cohesion may contribute to the sister chromatid separation of Δcdc55 in response to DNA damage. Our results reveal that PP2A plays dual roles in sister chromatid separation, one regulating centromeric cohesion without involvement of securin Pds1 and the other preventing precocious sister chromatid separation in response to spindle damage in a Pds1-dependent fashion.

PP2A Prevents Anaphase Entry by Modulating APCCdc20 Activity.

Why do the sister chromatids separate in Δcdc55 cells in the presence of spindle damage? It is well established that the presence of nocodazole activates spindle-assembly checkpoint that prevents the activation of APCCdc20, which is required for Pds1 proteolysis (35). Δcdc55 mutant cells failed to keep high Pds1 levels in the presence of nocodazole (Fig. 1 and ref. 18). Moreover, cleavage of Mcd1 and Slk19, the two known Esp1 substrates, was detected in nocodazole-treated Δcdc55 cells. Thus, it is very likely that APCCdc20 is hyperactive in Δcdc55 mutants, leading to Pds1 degradation and subsequent Esp1 liberation. Two lines of evidence also support this hypothesis. One is our previous finding that Δcdc55 mutant suppresses the temperature sensitivity of cdc20–1 (24), and the other is that inactivation of Cdc20 greatly reduces the sister chromatid separation in nocodazole-treated Δcdc55 cells.

It has been shown that the cyclin-dependent kinase phosphorylates APC components and promotes the association of APC with its activator Cdc20 (36–38). A mutant of the budding yeast cyclin-dependent kinase, CDC28VF, which is resistant to the inhibitory phosphorylation by Swe1, suppresses the sister chromatid separation in Δcdc55 mutants in the presence of nocodazole (23). Further studies reveal that the compromised cyclin-dependent kinase activity in Cdc28VF leads to decreased phosphorylation of APC/C components, and it is the less active APC/C that suppresses sister separation in Δcdc55 mutants (36, 38). Thus, a possible model would be that defects in PP2A result in hyperactive APCCdc20, which degrades Pds1 and leads to chromosome separation.

Possible Pathway in Which PP2A Might Play Its Role in Centromeric Cohesion.

It is interesting to note that Δcdc55 cells also exhibit precocious sister chromatid separation in the presence of DNA damage. In comparison to nocodazole-arrested Δcdc55 cells that exhibit similar frequencies of sister chromatid separation at telomere, centromere, and the URA3 loci, the cdc13–1-arrested Δcdc55 cells lose cohesion preferentially at centromeric regions. Although exhibiting separated sister chromatids, cdc13–1 Δcdc55 cells show persistent Pds1 and Mcd1 protein levels. Furthermore, Δcdc55 cells still separated the sister chromatids when Pds1 is overproduced. A Pds1-independent sister chromatid separation at centromeric regions has been described in smt4 mutants after DNA damage (30). The smt4 mutant allele originally was isolated from a genetic screen for mutants showing sensitivity to the DNA synthesis inhibitor hydroxyurea (30). We recently found that Δcdc55 and Δpph21 Δpph22 mutants also are sensitive to hydroxyurea (39). Given the observed resemblance of Δcdc55 and smt4 in centromeric cohesion defects and hydroxyurea sensitivity, Cdc55 and Smt4 may regulate sister chromatid cohesion in the same pathway. Further detailed analysis is needed to clarify this issue.

Although we established the role for PP2A in sister chromatid cohesion mainly by using Δcdc55 mutant, we believe that the holoenzyme of PP2A, acting as a whole, is involved in this process for the following reasons. First, mutants of the PP2A different subunits, namely Δcdc55, Δtpd3, and Δpph21 Δpph22, are all sensitive to spindle-depolymerizing drugs. More importantly, deletion of TPD3, which encodes the A regulatory subunit of PP2A, also leads to sister chromatid separation in both nocodazole- and DNA damage-arrested cells. Recent evidence indicates that the regulatory subunit B′ (Rts1), but not the regulatory subunit B (Cdc55), associates with the core enzyme of PP2A and the centromere protector SgoI to prevent centromere separation during meiosis (20–22). Because Δsgo1, Δcdc55, Δtpd3, Δpph21 Δpph22 mutant cells, but not Δrts1, exhibited dramatic benomyl sensitivity (unpublished data), Rts1 may not play a role in mitotic regulation. It is possible that Cdc55 replaces Rts1 to maintain centromeric cohesion in mitosis in budding yeast.

So far PP2A has been shown to play multiple roles during the cell cycle. In the present study we show that PP2A regulates chromosome separation in mitosis. Recent data from several groups also demonstrate a negative role of PP2A in mitotic exit (17–19). In view of the regulation of PP2A in chromosome behaviors and mitotic exit, it is easy to imagine the importance of PP2A in maintaining genomic integrity. It has been reported that mutation in PP2A is one of the six elements required for transformation of human cells (40). After stressful stimuli, cells with PP2A mutations may fail to maintain genomic integrity because of an inability to prevent anaphase entry and mitotic exit. Therefore, the functional studies of PP2A in budding yeast can potentially reveal its roles in cancer development in human.

Materials and Methods

Strains and Plasmids.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. All strains are isogenic with W303-derived Y300 strain and were constructed by standard genetic cross. The plasmid that expresses nondegradable Pds1(Pds1Δdb) under the control of a galactose-inducible promoter was constructed by excising the KpnI–SacI fragment from pOC58, which includes the pds1Δdb allele and the GAL promoter (5), and inserting it into the KpnI–SacI sites of pRS414 (41).

Microscopy and Western Blotting.

Detection of chromosomal GFP dots was performed as described (42, 43). Collected cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 5 min and then resuspended in 1× PBS buffer. The GFP dots were visualized under a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Crude protein extracts were prepared as described previously (17). Protein extracts were resolved on 10% SDS/PAGE followed by Western blotting with appropriate antibodies. Immunodetection was carried out with the Western-brightening system (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Stephen Elledge (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA), Angelica Amon (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA), Kim Nasmyth (University of Oxford, Oxford, U.K.), Frank Uhlmann (London Cancer Institute, London, U.K.), Jeff Bachant (University of California, Riverside, CA), and Vincent Guacci (Carnegie Institution of Washington, Baltimore, MD) for plasmids and strains. We thank Drs. Akash Gunjan and Jamila Horabin for reading through the manuscript. We thank Tuen-Yung Ng for preparing media and buffers for the experiments. This work was supported by an American Heart Association Scientist Development grant and by James and Esther King Biomedical Research Program 04NIR13 from Florida State Department of Health (to Y.W.).

Abbreviations

- PP2A

protein phosphatase 2A

- APC/C

anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Guacci V, Koshland D, Strunnikov A. Cell. 1997;91:47–57. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80008-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michaelis C, Ciosk R, Nasmyth K. Cell. 1997;91:35–45. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uhlmann F, Lottspeich F, Nasmyth K. Nature. 1999;400:37–42. doi: 10.1038/21831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciosk R, Zachariae W, Michaelis C, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Nasmyth K. Cell. 1998;93:1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen-Fix O, Peters JM, Kirschner MW, Koshland D. Genes Dev. 1996;10:3081–3093. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.24.3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uhlmann F, Wernic D, Poupart MA, Koonin EV, Nasmyth K. Cell. 2000;103:375–386. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoyt MA, Totis L, Roberts BT. Cell. 1991;66:507–517. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li R, Murray AW. Cell. 1991;66:519–531. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartwell LH, Weinert TA. Science. 1989;246:629–634. doi: 10.1126/science.2683079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hwang LH, Lau LF, Smith DL, Mistrot CA, Hardwick KG, Hwang ES, Amon A, Murray AW. Science. 1998;279:1041–1044. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5353.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanchez Y, Bachant J, Wang H, Hu F, Liu D, Tetzlaff M, Elledge SJ. Science. 1999;286:1166–1171. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang H, Liu D, Wang Y, Qin J, Elledge SJ. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1361–1372. doi: 10.1101/gad.893201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janssens V, Goris J. Biochem J. 2001;353:417–439. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3530417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans DR, Stark MJ. Genetics. 1997;145:227–241. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.2.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shu Y, Yang H, Hallberg E, Hallberg R. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3242–3253. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Healy AM, Zolnierowicz S, Stapleton AE, Goebl M, DePaoli-Roach AA, Pringle JR. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:5767–5780. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.11.5767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Ng TY. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:80–89. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-12-1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yellman CM, Burke DJ. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:658–666. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Queralt E, Lehane C, Novak B, Uhlmann F. Cell. 2006;125:719–732. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitajima TS, Sakuno T, Ishiguro K, Iemura S, Natsume T, Kawashima SA, Watanabe Y. Nature. 2006;441:46–52. doi: 10.1038/nature04663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang Z, Shu H, Qi W, Mahmood NA, Mumby MC, Yu H. Dev Cell. 2006;10:575–585. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riedel CG, Katis VL, Katou Y, Mori S, Itoh T, Helmhart W, Galova M, Petronczki M, Gregan J, Cetin B, et al. Nature. 2006;441:53–61. doi: 10.1038/nature04664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minshull J, Straight A, Rudner AD, Dernburg AF, Belmont A, Murray AW. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1609–1620. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70784-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Burke DJ. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:620–626. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.2.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weinert TA, Hartwell LH. Genetics. 1993;134:63–80. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garvik B, Carson M, Hartwell L. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6128–6138. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sullivan M, Lehane C, Uhlmann F. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:771–777. doi: 10.1038/ncb0901-771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Visintin R, Prinz S, Amon A. Science. 1997;278:460–463. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Csortos C, Zolnierowicz S, Bako E, Durbin SD, DePaoli-Roach AA. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2578–2588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bachant J, Alcasabas A, Blat Y, Kleckner N, Elledge SJ. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1169–1182. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00543-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stead K, Aguilar C, Hartman T, Drexel M, Meluh P, Guacci V. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:729–741. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D'Amours D, Stegmeier F, Amon A. Cell. 2004;117:455–469. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00413-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He X, Asthana S, Sorger PK. Cell. 2000;101:763–775. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80888-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goshima G, Yanagida M. Cell. 2000;100:619–633. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80699-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gardner RD, Burke DJ. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:154–158. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01727-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rudner AD, Hardwick KG, Murray AW. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1361–1376. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kraft C, Herzog F, Gieffers C, Mechtler K, Hagting A, Pines J, Peters JM. EMBO J. 2003;22:6598–6609. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rudner AD, Murray AW. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1377–1390. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu H, Wang Y. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:2746–2756. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen W, Possemato R, Campbell KT, Plattner CA, Pallas DC, Hahn WC. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:127–136. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sikorski RS, Hieter P. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y, Bachant J, Alcasabas AA, Wang Y, Qin J, Elledge SJ. Genes Dev. 2002;16:183–197. doi: 10.1101/gad.959402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alexandru G, Uhlmann F, Mechtler K, Poupart MA, Nasmyth K. Cell. 2001;105:459–472. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00362-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.