Abstract

Studies on Drosophila immunity have focused on the humoral response, whereas less is known about the Drosophila cellular immunity. Here we show that mutants that lack the Drosophila Rel/NF-κB proteins Dorsal and Dif have very few blood cells, are constitutively infected by opportunistic microbes, and die from infection as larvae. When the double mutants are grown in microbe-free conditions, the animals are rescued from chronic infection and many survive to adult stages. Thus, Dif and Dorsal are required for survival because they protect the animal from infection by microbes from the environment. Specific expression of Dif or dorsal in the blood cell lineage is sufficient to restore blood cell number, clear microbes, and allow survival to the adult stage. These findings demonstrate that the cellular immune response is essential for the ability of Drosophila to survive in their standard laboratory environment, and that Dif and Dorsal control crucial aspects of the cellular immune response, including blood cell survival and the ability to fight off microbial infection.

Keywords: innate immunity, macrophages, phagocytosis, humoral immune response

The conservation of innate immune responses has stimulated Drosophila genetic studies to identify and characterize new aspects of pattern recognition and immune signaling pathways (1). The best understood aspect of Drosophila immunity is the humoral response, in which microbial components activate the transcription of antimicrobial peptide genes in the fat body (the liver analogue) through the Toll and Imd pathways (2, 3). The responses to these humoral signaling pathways are regulated by the three Drosophila Rel transcription factors, Dorsal, Dif, and Relish. Relish, a compound Rel-Ank protein homologous to mammalian p100 and p105, is activated by the Imd pathway and is a direct transcriptional activator of antibacterial peptide gene expression (4). Dif and Dorsal, which are homologous to mammalian c-Rel and RelA, are activated by the Toll pathway, which is important for production of antimicrobial peptides that are active against fungi and Gram-positive bacteria in adult Drosophila (5, 6).

Drosophila has a cellular immune response, which is mediated by hemocytes (also known as blood cells) that circulate in the hemolymph (7). Experiments on mutants that lack nearly all their hemocytes showed that blood cells are not required for the production of antimicrobial peptides by the fat body after septic injury, but are important in the humoral response after natural infection (8). In addition, a specific cytokine that is induced in blood cells in response to septic injury has been shown to activate a humoral response in the fat body (9).

The vast majority of hemocytes are the professional phagocytic cells in Drosophila, which are similar to mammalian macrophages (4, 10). Phagocytosis of bacteria is known to play a role in host defense, because blocking of phagocytosis further impairs the ability of mutants with compromised humoral immune response to survive bacterial infection (11). In addition, adult Drosophila that lack Eater, a blood cell protein related to scavenger receptors, show increased sensitivity to the pathogenic bacterium Serratia marcescens, although not to Escherichia coli or the fungus Beauveria bassiana (12).

In addition to their roles in the humoral response, Drosophila Rel proteins have been implicated in the regulation of blood cell number because loss of Cactus, the IκB protein that inhibits Dif and Dorsal nuclear localization, causes a dramatic increase in blood cell proliferation (13). The overproliferation phenotype can be rescued by expression of the WT cactus gene in the blood cell lineage (ref. 13 and our unpublished data), which suggests that Rel proteins are present in the hemocyte lineage and promote hemocyte proliferation. However, mutants that lack any single Rel protein do not have detectable hemocyte phenotypes (refs. 4 and 13, and data not shown).

Here we show that Rel proteins are crucial regulators of the cellular immune response, and that in the absence of Dif and Dorsal, Drosophila larvae die of opportunistic infection. The double mutants are able to activate a humoral immune response, but that is not sufficient to prevent infection. Instead, Dif and Dorsal are also required in blood cells to control blood cell number and to enable blood cells to clear microbes from the hemolymph. Our experiments demonstrate that the cellular immune response is required for Drosophila to survive to adult stages, and that Rel proteins have central roles in the ability of blood cells to protect the animal from microbial infection.

Results

Dif dorsal Double Mutants Are Immunocompromised.

Single mutants that lack any one of the Drosophila Rel family genes, dorsal, Dif, or Relish, are fully viable and have no obvious morphological abnormalities. To test whether Rel proteins have overlapping functions, we generated the three possible double-mutant combinations. Relish Dif and Relish dorsal double-mutant larvae were smaller than WT, and about half of the double homozygotes died before reaching adult stages (data not shown). Dif dorsal double mutants were small and sluggish and only 3.4% (±3.4%) survived to adult stages (Table 1).

Table 1.

Blood cell number and survival in Dif dorsal double mutants

| Genotype | Antibiotic treatment | UAS line | Gal4 line | Target tissue | Hemocyte no./μl × 103 | Adult survival, % of expected | Infection status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | − | None | None | 5.2 ± 2.0 | 100 | − | |

| WT | + | None | None | 5.0 ± 2.1 | 100 | − | |

| Dif dorsal | − | None | None | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 3.4 | +++ | |

| Dif dorsal | + | None | None | 1.4 ± 1.2 | 33 | − | |

| Dif dorsal | − | UAS-p35 | Hemese-Gal4 | Blood cells | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 32 | + |

| Dif dorsal | − | UASp-dorsal | hs-Gal4 | Ubiquitous | ND | 100 | ND |

| e33C-Gal4 | Blood cells, lymph glands, epidermis | 4.3 ± 1.4 | 66 | − | |||

| Hemese-Gal4 | Blood cells | 16 ± 5.8 | 46 | − | |||

| srpHemo-Gal4 | Blood cells, lymph glands | 4.6 ± 2.3 | 48 | − | |||

| Dif dorsal | − | UAS-Dif | hs-Gal4 | Ubiquitous | ND | 130 | ND |

| Hemese-Gal4 | Blood cells | 41 ± 11 | 43 | − | |||

| srpHemo-Gal4 | Blood cells, lymph glands | 4.3 ± 1.0 | 44 | − |

Antibiotic-treated larvae were grown on minimal medium (see Materials and Methods). All other experiments were done on standard food. Target tissues of the Gal4 lines were determined in crosses with UAS-GFP flies. Hemocyte number was based on the average cell count of three to six animals for each genotype. Adult survival was calculated by comparing the number or rescued animals with heterozygous siblings (100%). Infection status was determined by counting the number of microbes in fields of 137 × 104 μm: +++, ≈105 microbes per animal; +, ≈103 microbes per animal. WT hemolymph samples do not have microbial infection. ND, not determined. In all rescue experiments, hemocyte numbers were significantly higher in UAS/Gal4 rescued animals than in Dif dorsal larvae (Student's t test, P < 0.005). The difference in hemocyte numbers between Dif dorsal and Dif dorsal treated with antibiotic was on the border of statistical significance (P = 0.12). Hemocyte numbers in Dif dorsal animals that were rescued by expression of either Dif or dorsal with e33-Gal4 and srpHemo-Gal4 were not significantly different from hemocyte numbers in WT larvae (Student's t test).

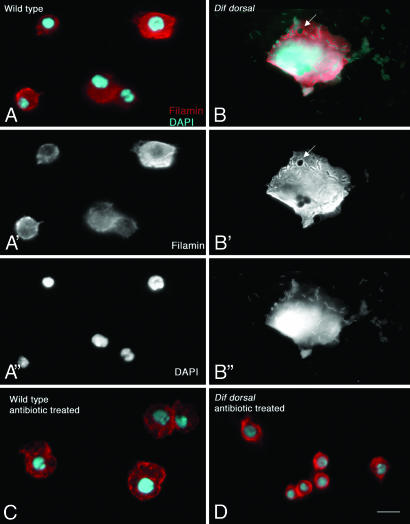

We pursued the analysis of Dif dorsal double mutants, the Rel mutant combination that had the strongest effect on viability. Because of the important roles of Rel proteins in immune responses, we investigated whether systemic infection might contribute to the lethality of the Dif dorsal double mutants. Although microbes were never observed in the hemolymph of uninfected WT larvae (Fig. 1A), unchallenged Dif dorsal larvae contained many bacteria (Fig. 1B) and yeast in their hemolymph (as many as 105 microbes per animal).

Fig. 1.

Hemocyte phenotypes in Dif dorsal double mutants. Hemocytes were labeled with Filamin antibody to visualize hemocyte morphology (red) and DAPI (cyan) to visualize nuclei and bacterial DNA. (A) Hemocytes and hemolymph samples from WT do not contain microbes. (A′) Filamin staining only. (A″) DAPI staining only. (B) Hemolymph and hemocytes from Dif dorsal mutants contain bacteria in the absence of experimentally introduced infection. (B′) Filamin staining only. (B″) DAPI staining only. Bacteria are present both in the hemolymph and inside the hemocyte (B, B″), whereas Filamin (B, B′) surrounds the intracellular bacteria. Vacuoles outlined by Filamin are present in Dif dorsal hemocytes (arrows in B and B′), but they do not contain bacteria. (C) Hemocytes from antibiotic-treated WT larvae resemble untreated WT hemocytes shown in A. (D) Hemocytes and the hemolymph from antibiotic-treated Dif dorsal larvae are microbe-free. (Scale bar: 10 μm.)

Infection Leads to the Death of Dif dorsal Double Mutants.

To test whether the lethality of Dif dorsal double mutants was due to the microbial infection or, alternatively, was the result of developmental defects, we grew the double-mutant animals in microbe-free conditions. It was necessary to raise the animals on a minimal medium and in the presence of antibiotics to eliminate microbes from the animals (see Materials and Methods). When grown under these conditions, 33% (±14%) of the Dif dorsal animals survived to adult stages, 10-fold more than those that survived under standard growth conditions in the same experiment (2.7% ± 2.6%). These results indicate that infection by microbes from the environment is a major cause of the lethality of Dif dorsal double mutants.

The Humoral Immune Response Is Active in Dif dorsal Double-Mutant Larvae but Does Not Protect the Animals from Opportunistic Infection.

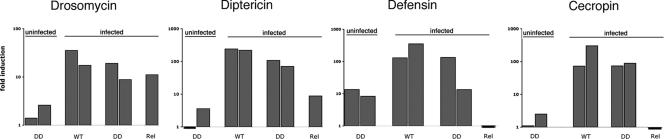

To determine whether the constitutive infection of Dif dorsal mutants was due to inability to induce the humoral immune response, we analyzed the expression of four antimicrobial peptide genes (Drosomycin, Diptericin, Defensin, and Cecropin C) by quantitative RT-PCR. Septic injury of WT larvae with either Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacteria induces expression of all antimicrobial peptide genes (14) and can be used as a reliable assay for the humoral response toward a broad variety of microbes. The quantitative RT-PCR showed that the four antimicrobial peptides genes were strongly induced in response to E. coli injection in WT larvae (Fig. 2 and Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). As reported previously, Relish-null mutant larvae failed to induce the Cecropin C and Defensin antibacterial peptide genes, showed greatly reduced induction of Diptericin, and showed moderate induction of the antifungal peptide gene Drosomycin (15, 16) (Fig. 2). Consistent with the presence of microbes in their hemolymph, we found that unchallenged Dif dorsal larvae showed expression of antimicrobial peptide genes in the absence of experimentally introduced infection; Defensin showed the greatest expression, with up to 14-fold higher levels than in uninfected WT animals (Fig. 2). Expression of all four antimicrobial peptide genes was further induced in Dif dorsal mutants in response to injected E. coli. For example, Diptericin was induced ≈100-fold above the base line level in response to E. coli injection (Fig. 2). Much stronger defects in the induction of Defensin, Diptericin, and Cecropin are seen in larvae that lack Relish or other components of the Imd pathway (Fig. 2) (4, 14, 17), but these animals are fully viable and are not constitutively infected by microbes. Therefore, the modest defect in antimicrobial peptide production cannot account for the microbial infection and death of Dif dorsal larvae. Thus, Dif dorsal double-mutant larvae are able to mount a humoral immune response, but the antimicrobial peptides do not prevent the constitutive infection of these animals.

Fig. 2.

Expression of antimicrobial peptide genes in Dif dorsal larvae. Expression of Drosomycin, Diptericin, Defensin, and Cecropin in WT, Dif dorsal and Relish mutant larvae, as assayed by Q-PCR in uninfected animals and in animals 2 h after injection of E. coli. Fold induction is calculated relative to WT uninfected larvae in all cases. Experiments with Dif dorsal (DD) and WT animals were repeated with two independent sets of animals (two bars). Numerical data are in Table 2. The statistical significance of the data was evaluated with Student's t test, using six values (two triplicate sets for each experiment) for the induction of each antimicrobial peptide. The expression level of all antimicrobial peptides in infected Dif dorsal larvae was significantly greater than that in uninfected Dif dorsal larvae (P < 0.05). The induction for Drosomycin, Diptericin, and Defensin in infected Dif dorsal larvae was significantly less than that in infected WT larvae (P < 0.05). The induction of Cecropin C in infected Dif dorsal larvae was not significantly different from infected WT larvae (P = 0.07).

Dif and Dorsal Proteins Are Required for Blood Cell Survival and Function.

Because the modest deficit in the humoral response of Dif dorsal double mutants was not sufficient to account for their phenotype, we tested whether defects in the cellular immune response could be responsible for the constitutive infection of Dif dorsal animals. Mutants that lack Cactus, the negative regulator of Dif and Dorsal, have increased numbers of blood cells (ref. 13 and our unpublished data). We therefore measured the number of blood cells in Dif dorsal larvae. WT and Dif dorsal/+ + heterozygotes had ≈5,000 blood cells per μl of hemolymph. In contrast, their Dif dorsal double-homozygous siblings had a greatly reduced number of hemocytes: there were ≈500 hemocytes per μl of circulating hemolymph, 10-fold fewer than WT (Table 1).

TUNEL staining revealed that ≈15% of Dif dorsal hemocytes were undergoing apoptosis, compared with only 2.3% in WT hemocytes (Table 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). To test whether the high rate of cell death accounted for the decreased number of blood cells in Dif dorsal animals, we expressed p35, an inhibitor of apoptosis, in the hemocyte lineage using UAS-p35 and Hemese-Gal4 transgenes (18, 19). In these experiments, the number of blood cells in Dif dorsal larvae increased 4 fold, to 2,200 (±600) cells per μl of hemolymph (Table 1), whereas the blood cell number remained constant in the heterozygous siblings. Therefore, the low number of blood cells in Dif dorsal larvae was due, at least in part, to loss of an antiapoptotic activity of Dif and Dorsal.

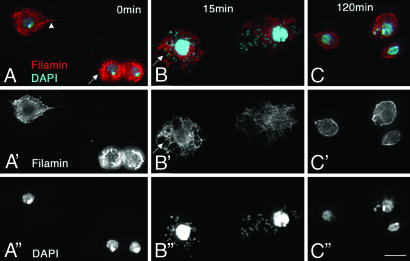

We then compared the morphology and function of WT and Dif dorsal larval hemocytes. To examine phagocytic cells, we stained hemocytes with an antibody that recognizes the Drosophila homologue of Filamin (20), an actin-binding protein that has been used to label mammalian macrophages (21, 22). Most WT hemocytes are phagocytic and are small cells with smooth cell surfaces (Fig. 3A, arrow) or larger cells with numerous microspikes (Fig. 3A, arrowhead) (4, 10, 23). As soon as 15 min after injection of E. coli, we found that individual WT blood cells had ingested as many as 30 bacteria that could be visualized by DAPI staining (Fig. 3B). The phagocytic cells were enlarged and had 25–30 cytoplasmic vacuoles that contained bacteria (Fig. 3B, arrow). By 2 h after infection, the hemocytes had digested the bacteria and regained the morphology and size of uninfected blood cells (Fig. 3 C and C′).

Fig. 3.

Phagocytosis and bacterial clearance by WT hemocytes. (A–C%) Hemocytes from WT third-instar larvae, labeled with the Filamin antibody (red) to highlight F-actin and DAPI (cyan) to visualize nuclear and bacterial DNA. (A′–C′) Staining with only Filamin highlights F-actin in the cell. (A″–C″). Staining with only DAPI highlights bacterial and nuclear DNA. (A, A′, and A″) Hemocytes from uninfected WT larvae are 6–15 μm in size. The larger macrophages extend pseudopodia (A, arrowhead). WT hemolymph samples do not contain bacteria. (B, B′, and B″) Phagocytic hemocytes 15 min after infection with E. coli are enlarged and contain bacteria, which are found inside vacuoles surrounded by Filamin (arrows in B and B′). (C, C′, and C″) Two hours after infection, hemocytes resemble uninfected blood cells, and bacteria are rarely seen in the hemolymph. (Scale bar: 10 μm.)

The few blood cells present in Dif dorsal larvae had abnormal morphology. In contrast to WT hemocytes, the Dif dorsal blood cells were enlarged cells containing intact intracellular bacteria that were not localized to vacuoles (Fig. 1B, arrow) and had not been digested. When Dif dorsal larvae were grown on minimal medium in the presence of antibiotics, the number of hemocytes increased 3-fold, to ≈1,400 cells per μl (Table 1), and these hemocytes were of normal morphology (Fig. 1D). These results imply that chronic infection contributes to blood cell apoptosis when both Dif and Dorsal are absent.

To test whether Dif and Dorsal have specific roles in bacterial clearance, we injected E. coli into Dif dorsal double-mutant larvae in which blood cell apoptosis was prevented by expression of p35 in the hemocyte lineage. Most animals of this genotype still had microbes in the hemolymph (Fig. 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), but the microbial loads were 100-fold lower than in unrescued Dif dorsal larvae (Table 1 and Fig. 5). After injection with E. coli, nearly all of the p35-rescued Dif dorsal larvae became flaccid and died within a few hours. At 5 h after infection, the few surviving p35-rescued Dif dorsal animals had up to 1,000 times more bacteria per animal than did WT larvae (Table 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Bacteria were engulfed by the p35-rescued hemocytes but were not digested, and many of the hemocytes had ruptured (Fig. 5). The results indicate that Dif and Dorsal are required for bacterial clearance in addition to their role in the prevention of blood cell apoptosis.

Dif and dorsal Are Required Cell Autonomously for Hemocyte Number and Function.

To determine whether Dif and Dorsal act autonomously in blood cells to prevent infection, we used the UAS/GAL4 system to express dorsal or Dif in the blood cell lineage (see Materials and Methods and ref. 24) and assayed for rescue of the Dif dorsal mutant phenotypes. Ubiquitous expression of either UAS-Dif or UAS-dorsal driven by heat-shock-Gal4 (hs-Gal4) at 25°C (without heat shock) fully rescued the lethality of Dif dorsal double mutants, which indicated that expression of either gene could compensate for the absence of the other. Animals are very sensitive to the levels of the Rel proteins: overexpression of Dif or dorsal with hs-Gal4 at 37°C (1-h pulses) was lethal, so all experiments were designed to express the proteins at levels as close to the WT as possible.

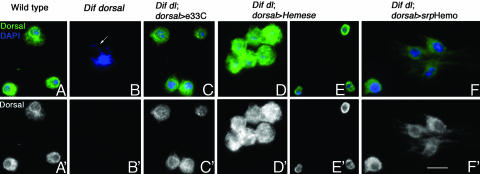

We used three different Gal4 drivers to express Dif or dorsal in Dif dorsal mutants in circulating blood cells. The e33C-Gal4 line drives expression in circulating hemocytes, lymph glands, and epidermis, but not in the fat body (see Materials and Methods). Expression of dorsal under the control of the e33C-Gal4 line restored normal hemocyte numbers. The dorsal-rescued blood cells had approximately WT levels of Dorsal protein, as judged by staining with Dorsal antibody, and were indistinguishable in morphology from WT uninfected hemocytes (Fig. 4). In addition, the rescued animals had no microbes in their hemolymph, and 66% survived to adult stages (Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Rescue of the Dif dorsal hemocytes by expression of Dorsal in hemocytes. (A–F%) Hemolymph samples stained with Dorsal antibody (green) and DAPI (blue). (A′–F′) Dorsal antibody staining only. (A and A′) Dorsal is cytoplasmic in WT hemocytes. (B and B′) Dif dorsal mutant hemocytes do not express Dorsal. Macrophages contain bacteria (arrow) in the absence of introduced infection. (C and C′) Hemocytes from Dif dorsal larvae that express UASp-dorsal under the control of e33C-Gal4 line are not constitutively infected (compare B with C). The rescued hemocytes express Dorsal protein at levels that are similar to WT hemocytes (compare A′ with C′, Dorsal staining only). (D and D′ and E and E′) Some hemocytes from Dif dorsal larvae that express UASp-dorsal under the control of Hemese-Gal4 show both cytoplasmic and nuclear Dorsal staining (D and D′), whereas most hemocytes (80%) show only cytoplasmic staining (E and E′). Dorsal staining is brighter than in WT hemocytes (compare A′ with D′ and E′). (F and F′) Hemocytes from Dif dorsal larvae that express UASp-dorsal under the control of the srpHemo-Gal4 line are microbe-free and express Dorsal at levels similar to WT hemocytes (compare A′ with F′). (Scale bar: 10 μm.)

The Hemese-Gal4 line directs expression in circulating hemocytes, but not in other immune-responsive tissues (see Materials and Methods, Table 1, and ref. 19). Hemese-Gal4 appeared to cause moderate overexpression of Dif and dorsal, because the number of hemocytes was severalfold higher than in WT (Table 1). In addition, although 80% of the hemocytes showed only cytoplasmic staining of Dorsal (Fig. 4 E and E′), Dorsal was present in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus in 20% of the hemocytes (Fig. 4 D and D′). Nevertheless, Dif dorsal animals that expressed Dif or dorsal under control of Hemese-Gal4 had no microbes in their hemolymph, and ≈45% survived to become adults.

The srpHemo-Gal4 line directs expression of normal levels of Dorsal in a variable fraction (22–55%) of circulating blood cells and lymph gland cells (see Materials and Methods). Expression of dorsal with the srpHemo-Gal4 line increased blood cell number to ≈90% of WT and allowed survival of ≈50% of the animals to adulthood (Table 1). The majority of these larvae had no microbes in their hemolymph (Fig. 4F).

Because the only overlap in expression of these three GAL4 drivers was in the circulating hemocytes, our experiments showed that expression of dorsal or Dif in blood cells of Dif dorsal double mutants was sufficient to rescue all phenotypes detected in these animals. The surviving adults did not have morphological defects, suggesting that the essential function of Dif and Dorsal is specific to blood cells. Because none of these lines drive expression in the fat body, clearance of microbes from the hemolymph did not require Dif or Dorsal in the fat body, the organ that is principally responsible for the production of antimicrobial peptides. Instead, blood cell number, microbial clearance, and viability of the animal depend on Rel protein activity in the blood cells.

Discussion

Drosophila that lack the humoral immune response survive to adulthood, and their immune deficit is revealed only after exposure to high titers of pathogenic microbes or after injection of bacteria into the hemocoel (4, 14, 17, 25). It has therefore been inferred that the Drosophila immune response is required only when the animal is exposed to pathogenic organisms. In contrast to this view, we find that Drosophila that lack the Rel proteins Dif and Dorsal are infected with microbes from the environment and that 97% of these animals die as larvae, whereas Dif dorsal animals grown in microbe-free conditions are 10 times more likely to survive to adult stages. Thus, Dif and Dorsal are required to prevent infection, and most animals die without this protection.

Our experiments demonstrate that Dif and Dorsal exert their effects through the second arm of the immune response, the cellular response. Expression of Dif or Dorsal in circulating blood cells is sufficient to protect Dif dorsal larvae from infection. Depending on the Gal4 driver, 43–66% of the Dif dorsal animals that expressed Dif or dorsal in the blood cell lineage survive to become adults (10–20 times the unrescued number), and the surviving animals have no detectable morphological defects. These results argue that a primary site of action of Dif and Dorsal is in the blood cell lineage, where they protect the animal from microbial infection. Although expression of the Rel proteins in the blood cells or antibiotic treatment did not lead to survival of 100% of Dif dorsal animals, it may not be possible to use the UAS/GAL4 system to express Rel proteins at exactly the correct level and time, and some microbes from the environment may be resistant to the antibiotic treatment. We therefore propose that Dif and Dorsal may be required for survival exclusively because of their roles in host defense.

Our studies show that Rel proteins act autonomously to control several aspects of blood cell function. In the absence of both Dif and Dorsal, blood cell number is greatly reduced. Many double-mutant blood cells are apoptotic, and expression of the apoptosis inhibitor p35 in blood cells partially rescues hemocyte number, which demonstrates that Dif and Dorsal are required in blood cells to prevent apoptosis. Antibiotic treatment also increases the number of blood cells and dramatically improves hemocyte morphology (Fig. 1D and Table 1), which shows that infection causes hemocyte apoptosis and necrosis in Dif dorsal double mutants. We suggest that Dif and Dorsal regulate the production or compartmentalization of microbicidal products inside blood cells, and that in the absence of the Rel proteins, infection triggers death of blood cells rather than ingested microbes.

Dif and Dorsal also act in blood cells to promote proliferation. Dorsal is constitutively nuclear in cactus mutant hemocytes (data not shown), and these cells have a higher mitotic index and increased BrdU incorporation (ref. 13 and our unpublished data). In addition, overexpression of either Dif or dorsal in hemocytes increases the number of circulating hemocytes (Table 1 and ref. 26). The roles of Rel proteins in the control of blood cell apoptosis and proliferation appear to be ancient, because they are remarkably conserved from Drosophila to mammals (27, 28).

In addition to the roles of Rel proteins in the regulation of blood cell number, Dif and Dorsal are required in blood cells to promote microbial clearance. WT blood cells are efficient phagocytes that are able to clear thousands of bacteria injected into the hemolymph within an hour. Dif dorsal double-mutant blood cells can engulf bacteria, but many bacteria remain in the hemolymph and undigested bacteria are present inside hemocytes. Even when blood cell number is increased by expression of the caspase inhibitor p35, Dif dorsal blood cells are unable to clear bacteria from the hemolymph. In contrast, expression of Dif or Dorsal in circulating blood cells fully rescues the ability of Dif dorsal larvae to clear infection. We therefore infer that Dif and Dorsal act in blood cells to control systemic infection, most probably by regulation of phagocytosis or digestion of engulfed microorganisms. A similar role for Rel proteins in mammalian phagocytosis has not been described, perhaps because functions of the five Rel family members overlap. Because of the evolutionary conservation of other aspects of Rel protein function in cellular innate immunity, we predict that Rel proteins will also play a role in phagocytosis and microbial clearance by mammalian phagocytic cells.

Whereas previous studies showed that Drosophila blood cells have a significant role in the production of cytokines that activate other immune responsive tissues, our results demonstrate that blood cells have an additional and more direct role in host defense. We find that the primary defense against microbial infection in Drosophila larvae is phagocytosis by blood cells in a cell-autonomous, Rel-dependent manner. The targets of Rel proteins in blood cells that mediate microbial clearance are not known, but future studies that take advantage of Drosophila molecular and genetic tools should define important and evolutionarily conserved dimensions of this aspect of the innate immune response.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila Stocks and Germ-Line Transformation.

Dif dorsal double mutants were of the genotype Df(2L)J4/Df(2L)TW119 (6). Relish mutants were homozygous for the null allele RelishE20 (4). Dif mutants were Dif1/Df(2L)J4 and dorsal mutants were dorsal1/Df(2L)J4. Dif1 and dorsal1 are null alleles (5, 29). Gal4 lines e33C-Gal4, srpHemo-Gal4, and Hemese-Gal4 were obtained from N. Perrimon (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA), K. Brückner (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA), and D. Hultmark (Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden), respectively. UAS-Dif flies were a gift from Y. T. Ip (University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA). UAS-p35 flies were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center (Indiana University, Bloomington).

To construct the UASp-dorsal transgene, a 2.2-kb HindIII fragment containing the dorsal cDNA was excised from pBP4-dorsal provided by D. Stein (University of Texas, Austin, TX). This fragment was subcloned in the HindIII site of pET-28a and then excised as a NotI/XbaI fragment. The NotI/XbaI fragment was subcloned in the NotI/XbaI sites of the UASp vector (30). The UASp-dorsal plasmid was injected along with the Δ2-3 transposase into w1118 syncytial blastoderm embryos according to standard techniques (31). All experiments were done with the homozygous viable line UASp-dorsal-7.

Infection, Hemocyte Counts, and Antibiotic Treatment.

Third-instar nonwandering larvae were used in all experiments. The morphology of the anterior spiracles was used as the base for staging. Larvae were punctured with a glass needle and dipped into an overnight culture of ampicillin-resistant E. coli DH5α (15). The infected animals were transferred to apple-juice agar plates and incubated at 22°C. Hemolymph was collected from three to six animals at the indicated time after E. coli infection by making a small incision at the posterior end and allowing the hemolymph to flow onto a microscope slide. Hemocyte counts were determined by mixing 1 μl of hemolymph with 1–3 μl of Ringer's buffer in an improved Neubauer counting chamber (Hausser Scientific, Horsham, PA). Hemocyte numbers are represented as cells per μl of hemolymph.

Double-mutant larvae grown on standard Drosophila cornmeal/molasses media in the presence of penicillin/streptomycin still had bacteria in their hemolymph. Some of the antibiotic-resistant bacteria were Gram-positive Bacillus, based on the morphology and Gram staining of cells grown on yeast extract/peptone/dextrose plates at 30°C. Twelve to 30 yeast colonies per larva and 10–12 bacterial colonies per larva grew under these conditions. To further reduce the number of microbes infecting the larvae, animals were grown on minimal medium: apple juice plates (25% vol/vol apple juice, 2.25% wt/vol powdered agar, and 2.5% wt/vol sucrose) (32), supplemented with autoclaved yeast. For antibiotic treatment, 100 μl of 100× penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine stock (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was allowed to absorb into the apple juice plate (50-mm plate) for 8 h. After eggs were laid on standard plates, first-instar larvae were transferred to apple juice plates containing antibiotics and autoclaved yeast. Thirty microliters of antibiotic was added to the apple juice plates every third day thereafter. In all cases, no bacterial colonies or only single bacterial colonies could be cultured on LB or yeast extract/peptone/dextrose plates.

Immunocytochemistry and Microscopy.

Hemolymph samples were collected in a drop of Ringer's solution (130 mM NaCl/4. 7 mM KCl/1. 9 mM CaCl2/10 mM Hepes, pH 6.9) on a microscope slide. Hemocyte smears were allowed to dry, and then were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, washed in PBS, and blocked for 30 min in 10% normal goat serum, then incubated overnight with the primary antibody. Staining with Filamin antibody (20) was used to outline F-actin in the cell. Filamin antibody was used at a 1:2,000 dilution and the Dorsal antibody (33) was diluted 1:1. The slides were washed in 1× PBS and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with Alexa-488 and Alexa-568-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). After a 1× PBS wash, the slides were incubated with DAPI (4 mg/ml) for 30 min at room temperature. Slides were washed in 1× PBS and mounted in fluorescence mounting medium for examination.

TUNEL was carried out as described in ref. 34. Cells were fixed on a slide in 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 min at room temperature. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched in 0.1% H2O2 for 15 min. The labeling reaction with terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase biotin-dUTP mix (Boehringer, Ingelheim, Germany) was done for 1–2 h at 37°C. Slides were covered with avidin-biotin-HRP (VECTASTAIN ABC kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 1 h. Biotinylated dUTP was visualized by using diaminobenzidine supplemented with H2O2.

Images of immunofluorescent hemocytes were collected with an Axiovert 200M (Zeiss, Chester, VA) equipped with Retiga EX camera (QImaging, Burnaby, BC, Canada) and the MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging, Downingtown, PA). Images were further processed with the AutoDeblur deconvolution software (AutoQuant, Silver Spring, MD).

Tissue-Specific Expression of Dif and dorsal.

Df(2L)J4 and Df(2L)TW119 are overlapping deletions that remove Dif, dorsal, an uncharacterized gene (6), and two annotated ORFs; one of the ORFs is not supported by ESTs and may be a pseudogene. Dif dorsal double mutants came from crosses of Df(2L)J4/T(2;3)CyO;TM6B to Df(2L)TW119/T(2;3)CyO;TM6B or Df(2L)J4/CyO, actin-GFP to Df(2L)TW119/CyO, arm-GFP animals. Dif dorsal larvae were identified by the absence of GFP fluorescence or the absence of the Tubby phenotype. For rescue experiments, the UASp-dorsal transgene was recombined onto the Df(2L)J4 chromosome, and srpHemo-Gal4 transgene was recombined onto the Df(2L)TW119 chromosome. All other Gal4 lines mapped to the third chromosome. A third-chromosome insertion of UAS-Dif line was used in all experiments. In survival tests, 200–800 adults were scored for each cross with UAS/Gal4 transgenes. Percent survival was determined by comparing the number of Dif dorsal double mutants that carried both the UAS and Gal4 transgenes and the number of Dif dorsal/+ + heterozygous siblings from the same cross (defined as 100%). For each genotype analyzed, hemolymph from three to six Tb+ or GFP− larvae was analyzed. Expression of UAS-Dif with the e33C-Gal4 caused lethality in either WT or Dif dorsal mutant background. Simultaneous expression of UAS-Dif and UAS-cactus with e33C-Gal4 produces viable adults, indicating that the lethality was due to overexpression of Dif.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (Q-PCR).

Third-instar larvae were harvested 2 h after infection with E. coli and homogenized, and RNA was prepared by using RNA STAT-60 (Tel-Test, Friendswood, TX). Later time points were not evaluated because few Dif dorsal animals survived longer than 2 h after infection. Quality of RNA was ensured before processing by analyzing 20–50 ng of each sample by using the RNA 6000 NanoAssay and a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA). One microgram of total RNA was reverse-transcribed by using the Thermoscript RT-PCR system (Invitrogen) at 52°C for 1 h. Twenty nanograms of the resulting cDNA was used in a Q-PCR with an iCycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and predesigned TaqMan gene expression assays for Diptericin (Dm01841768_s1), Cecropin C (Dm02151846_gH), Drosomycin (Dm01822006_s1), Defensin (Dm01818074_s1), and RpL32 (Dm02151827_s1) (Applied Biosystems). Amplification was carried for 40 cycles (95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 1 min). For all of the genes, relative amounts were normalized to RpL32. Fold changes were first calculated by using the equation fold change = 2−ΔCT, where CT is threshold cycle and ΔCT = [CT(gene of interest) − CT(RpL32)] (35). Triplicate CT values were averaged. Quantitation of mRNA levels and fold changes was repeated by using standard curves built for individual antimicrobial peptide genes. The two methods gave similar results. The results presented in Fig. 2 and Table 2 are based on the standard curve method.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Katia Manova and the Sloan–Kettering Institute Molecular Cytology Core Facility for their support. We thank Agnes Viale and the Sloan–Kettering Institute Genomics Core Facility for help with the Q-PCR. We thank Tony Ip for the UAS-Dif transgenic stocks, Dan Hultmark for Hemese-Gal4, K. Brückner for srpHemo-Gal4, Lynn Cooley and Nick Sokol for the Filamin antibody, Ruth Steward for the Dorsal antibody, Norbert Perrimon for the Gal4 lines, and the Drosophila Stock Center in Bloomington, IN, for stocks. We thank Anderson laboratory members, Hsiou-Chi Liou, and Tim Bestor for comments on the manuscript. The work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI45149 (to K.V.A.), a fellowship from the Irvington Institute for Immunological Research (to N.M.), and the Lita Annenberg Hazen Foundation.

Abbreviation

- Q-PCR

quantitative real-time PCR.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest

This article is a PNAS direct submission.

References

- 1.Mylonakis E, Aballay A. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3833–3841. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.3833-3841.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hultmark D. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:12–19. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanji T, Ip YT. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hedengren M, Asling B, Dushay MS, Ando I, Ekengren S, Wihlborg M, Hultmark D. Mol Cell. 1999;4:827–837. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutschmann S, Jung AC, Hetru C, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA, Ferrandon D. Immunity. 2000;12:569–580. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meng X, Khanuja BS, Ip YT. Genes Dev. 1999;13:792–797. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rizki TM. In: The Genetics and Biology of Drosophila. Ashburner M, Wright TRF, editors. Vol 2b. New York: Academic; 1978. pp. 397–452. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basset A, Khush RS, Braun A, Gardan L, Boccard F, Hoffmann JA, Lemaitre B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3376–3381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070357597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agaisse H, Petersen UM, Boutros M, Mathey-Prevot B, Perrimon N. Dev Cell. 2003;5:441–450. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00244-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanot R, Zachary D, Holder F, Meister M. Dev Biol. 2001;230:243–257. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elrod-Erickson M, Mishra S, Schneider D. Curr Biol. 2000;10:781–784. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00569-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kocks C, Cho JH, Nehme N, Ulvila J, Pearson AM, Meister M, Strom C, Conto SL, Hetru C, Stuart LM, et al. Cell. 2005;123:335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qiu P, Pan PC, Govind S. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1998;125:1909–1920. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.10.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choe KM, Werner T, Stoven S, Hultmark D, Anderson KV. Science. 2002;296:359–362. doi: 10.1126/science.1070216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu Y, Wu LP, Anderson KV. Genes Dev. 2001;15:104–110. doi: 10.1101/gad.856901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choe K-M. New York: Cornell Univ; 2002. PhD dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottar M, Gobert V, Michel T, Belvin M, Duyk G, Hoffmann JA, Ferrandon D, Royet J. Nature. 2002;416:640–644. doi: 10.1038/nature734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hay BA, Wolff T, Rubin GM. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1994;120:2121–2129. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.8.2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zettervall CJ, Anderl I, Williams MJ, Palmer R, Kurucz E, Ando I, Hultmark D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14192–14197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403789101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sokol NS, Cooley L. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1221–1230. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80502-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stossel TP, Condeelis J, Cooley L, Hartwig JH, Noegel A, Schleicher M, Shapiro SS. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:138–145. doi: 10.1038/35052082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stendahl OI, Hartwig JH, Brotschi EA, Stossel TP. J Cell Biol. 1980;84:215–224. doi: 10.1083/jcb.84.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rizki MTM. J Morphol. 1957;100:437–459. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brand AH, Perrimon N. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tzou P, Reichhart JM, Lemaitre B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2152–2157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042411999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang L, Ohsako S, Tanda S. Dev Biol. 2005;280:407–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grossmann M, Metcalf D, Merryfull J, Beg A, Baltimore D, Gerondakis S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11848–11853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rayet B, Gelinas C. Oncogene. 1999;18:6938–6947. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isoda K, Roth S, Nüsslein-Volhard C. Genes Dev. 1992;6:619–630. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.4.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rörth P. Mech Dev. 1998;78:113–118. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spradling A. In: Drosophila: A Practical Approach. Roberts DB, editor. Oxford: IRL; 1986. pp. 175–197. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wieschaus E, Nüsslein-Volhard C. In: Drosophila: A Practical Approach. Roberts DB, editor. Oxford: IRL; 1986. pp. 199–277. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whalen AM, Steward R. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:523–534. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.3.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gavrieli Y, Sherman Y, Ben-Sasson SA. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:493–501. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.3.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.