Abstract

Cytokinins, which are central regulators of cell division and differentiation in plants, are adenine derivatives carrying an isopentenyl side chain that may be hydroxylated. Plants have two classes of isopentenyltransferases (IPTs) acting on the adenine moiety: ATP/ADP isopentenyltransferases (in Arabidopsis thaliana, AtIPT1, 3, 4–8) and tRNA IPTs (in Arabidopsis, AtIPT2 and 9). ATP/ADP IPTs are likely to be responsible for the bulk of cytokinin synthesis, whereas it is thought that cis-zeatin (cZ)-type cytokinins are produced possibly by degradation of cis-hydroxy isopentenyl tRNAs, which are formed by tRNA IPTs. However, these routes are largely hypothetical because of lack of in vivo evidence, because the critical experiment necessary to verify these routes, namely the production and analysis of mutants lacking AtIPTs, has not yet been described. We isolated null mutants for all members of the ATP/ADP IPT and tRNA IPT gene families in Arabidopsis. Notably, our work demonstrates that the atipt1 3 5 7 quadruple mutant possesses severely decreased levels of isopentenyladenine and trans-zeatin (tZ), and their corresponding ribosides, ribotides, and glucosides, and is retarded in its growth. In contrast, these mutants possessed increased levels of cZ-type cytokinins. The atipt2 9 double mutant, on the other hand, lacked isopentenyl- and cis-hydroxy isopentenyl-tRNA, and cZ-type cytokinins. These results indicate that whereas ATP/ADP IPTs are responsible for the bulk of isopentenyladenine- and tZ-type cytokinin synthesis, tRNA IPTs are required for cZ-type cytokinin production. This work clarifies the long-standing questions of the biosynthetic routes for isopentenyladenine-, tZ-, and cZ-type cytokinin production.

Since the discovery of cytokinins as inducers of plant cell division (1) and differentiation (2), they have been recognized as central regulators of plant development (3). Cytokinins also increase nutrient sink strength, delay senescence, stimulate outgrowth from lateral buds, and inhibit cell elongation (4). The important roles for cytokinins in cell division were verified by overexpression of genes for cytokinin-degrading enzymes (cytokinin oxidases, CKXs) (5–7) and by examination of single and higher-order cytokinin-receptor null mutants (8–10).

Most naturally occurring cytokinins are N6-isopentenyladenine (iP) derivatives. iP carries an unmodified isopentenyl side chain, whereas trans-zeatin (tZ) and cis-zeatin (cZ) carry hydroxylated side chains. Cytokinins exist in free-base, riboside, and ribotide forms, with varying degrees of biological activity. Cytokinins also may be modified in several ways. For example, the N7 and N9 positions of the adenine moiety of cytokinins may be glucosylated to form N-glucosides. Alternatively, the hydroxyl group of tZ and cZ may be glucosylated or xylosylated to form zeatin-O-glucosides or zeatin-O-xylosides. N- and O-glycosides are biologically inactive (3).

Experimental evidence demonstrates that free-base cytokinins are biologically active. For example, iP (11) and tZ (12) were demonstrated to bind to the well characterized cytokinin receptor CRE1 and activate downstream cytokinin-dependent phosphorelay (11, 13–15). The riboside isopentenyladenosine (iPR) did not compete with radiolabeled iP for binding to a membrane fraction of Schizosaccharomyces pombe-expressing CRE1 (11). Similarly, the glucosylated cytokinin, zeatin O-glucoside (ZOG), did not compete with radio-labeled tZ for binding to E. coli cells expressing CRE1 (12). However, the riboside trans-zeatin riboside (tZR) did compete with radiolabeled tZ for binding to E. coli cells expressing CRE1, albeit with less affinity than unlabeled tZ (12). In many plant species, tZ is more abundant and more active than cZ (16); however, in some species, cZ is an abundant and biologically active cytokinin (17, 18).

In Dictyostelium discoideum, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, and plant tissues transformed with A. tumefaciens, cytokinins are produced by isopentenylation of AMP. This reaction is catalyzed by adenylate isopentenyltransferases (AMP IPTs) (19–22). In plants, AtIPT4 isopentenylate ATP and ADP, forming isopentenyl ATP and isopentenyl ADP, using dimethylallyldiphosphate as the side-chain donor (23). AtIPT1 also could isopentenylate AMP (3), but the KM for isopentenylation of AMP was significantly higher than that measured for ATP or ADP (24), indicating that isopentenylation of AMP is only a minor reaction carried out by the enzyme. The Arabidopsis genome encodes seven genes belonging to a plant-specific ATP/ADP IPT clade (AtIPT1, AtIPT3, AtIPT4, AtIPT5, AtIPT6, AtIPT7, and AtIPT8) (20, 23, 24). Overexpression of AtIPT4 or AtIPT8 confers cytokinin-independent shoot formation on calli (23, 25), and overexpression of AtIPT1, 3, 4, 5, 7, or 8 causes increased iP-type cytokinin levels in planta (25, 26). These results suggest that isopentenylation of ATP and ADP makes a major contribution to the control of cytokinin biosynthesis.

tZ ribotides are formed by the monooxygenase-catalyzed hydroxylation of the side chain of iP ribotides (27). Another pathway of tZ production, the iPR monophosphate-independent pathway, most likely involves transfer of the trans-hydroxylated isopentenyl moiety from 4-hydroxy-3-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl diphosphate to adenosine phosphates, by the action of AtIPTs (28). However, this pathway has become less favored since the finding that AtIPT1 does not efficiently catalyze transfer of the trans-hydroxylated isopentenyl moiety from the likely precursor, 4-hydroxy-3-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl diphosphate, to adenosine phosphates (26).

Each member of the ATP/ADP IPT gene family has a unique spatial expression pattern (29). Expression of AtIPT3, 5, and 7 is relatively high in the vegetative organs. AtIPT8 is expressed exclusively in reproductive organs, with highest expression in immature seeds. AtIPT4 is expressed primarily in reproductive immature seeds. AtIPT1 is expressed in ovules and vegetative organs. AtIPT1, 3, 5, and 7 are negatively regulated by cytokinins (29), whereas the effects of cytokinins on AtIPT4, 6, and 8 have not been examined.

In tRNAs recognizing codons beginning with U, the adenine residue immediately 3′ to the anticodon may be modified to have the isopentenyl- or cis-hydroxy isopentenyl- side chain at the N6 position (30). Therefore, it is possible that iP and cZ are produced when modified tRNAs are degraded. In bacteria, modified tRNAs are a source of low-level cytokinin production (31, 32); however, there is no experimental evidence for a tRNA-degradation route for cZ production in plants. tRNA IPTs catalyze isopentenylation of certain tRNAs in diverse organisms ranging from bacteria to animals and plants (33), including Arabidopsis (34). In the case of the bacterium Salmonella typhimurium, the isopentenyl chain of tRNA is hydroxylated at the cis position by the miaE gene product (35). It is unknown whether cis hydroxylation of isopentenylated tRNAs in plants occurs in a similar way. Arabidopsis has two genes (AtIPT2 and AtIPT9) encoding products homologous to tRNA isopentenyltransferases (tRNA IPTs). Furthermore, AtIPT2 has been shown to complement a yeast mutant deficient in tRNA isopentenyltransferase activities encoded by the MOD5 gene product (34). tRNA IPT genes are ubiquitously expressed in Arabidopsis tissues (29).

As described above, isopentenylation of ATP and ADP, by ATP/ADP IPTs, is likely the key step in biosynthesis of iP- and tZ-type cytokinins. However, it is still possible that other pathways contribute to cytokinin production. Important questions yet to be answered include whether ATP/ADP IPTs are responsible for the bulk of iP- and tZ-type cytokinin production in vivo, and to what extent modified tRNAs contribute to the production of iP-, tZ-, and cZ-type cytokinins. To answer these questions, we isolated mutant alleles for every ATP/ADP IPT and tRNA IPT, and made several higher-order IPT mutant plants to clarify the role of IPTs in cytokinin biosynthesis in planta.

Results

Isolation of Mutants for Every IPT.

Arabidopsis has seven genes for ATP/ADP IPTs (AtIPT1, AtIPT3, AtIPT4, AtIPT5, AtIPT6, AtIPT7, and AtIPT8) and two genes for tRNA IPTs (AtIPT2 and AtIPT9). We obtained T-DNA insertion mutants for all AtIPTs except AtIPT6 and AtIPT8. Because the T-DNA insertions were exonic for AtIPT1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7, these likely represent null alleles. The atipt9-1 allele contains an intronic insertion. However, a full-length AtIPT9 transcript could not be amplified by RT-PCR (Fig. 1B), suggesting that the T-DNA was not spliced-out. AtIPT6 is nonfunctional in the Wassilewskija (Ws) ecotype owing to a deletion of the 556th nucleotide relative to the translation start site, causing a frame-shift. We designate the wild type Ws line as atipt6-1. Because T-DNA insertion mutant was unavailable for AtIPT8, the AtIPT8 gene was targeted with 35S::NPTII flanked by upstream and downstream regions of AtIPT8, by homologous recombination. Thus we have collected putative null alleles for every AtIPT gene (Fig. 1A). No single mutant for an ATP/ADP IPT exhibited a visible phenotype. In this report, we omit allele numbers for atipt1-1, atipt2-1, atipt 3-2, atipt5-2, atipt7-1, and atipt9-1, which are Columbia ecotype, and for atipt4-1 and atipt6-1, and atipt8-1with Ws background. For other alleles, allele numbers are shown.

Fig. 1.

Mutants of AtIPT genes. (A) Description of the mutant alleles used in this study. T-DNA insert positions within the AtIPT1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 9 are represented by a triangle. The atipt6 mutation is indicated by alignment of short sequences corresponding to the region of AtIPT6 differing between Col and Ws. The atipt8 mutation is represented by a schematic of the construct used for deletion of the gene by homologous recombination. Coding regions are depicted with open squares, and noncoding regions are depicted with bars. NPTII, NEOMYCIN PHOSPHOTRANSFERASE II. (B) Expression of AtIPT9 in wild-type and atipt9-1. Because the T-DNA was inserted in an intron in the atipt9-1allele, expression of AtIPT9 was examined. RT-PCR was performed on cDNA derived from Col WT or atipt9-1plants by using primers upstream and downstream of the T-DNA insert. The 18S rRNA gene was used as a control. PCR cycles were 35 cycles for the AtIPT9 gene and 20 cycles for the 18S rRNA gene.

Growth of Mutants for ATP/ADP IPTs.

The three most highly expressed genes for ATP/ADP IPTs in the vegetative phase are AtIPT3, AtIPT5, and AtIPT7. AtIPT1 is also expressed in the vegetative phase at a low level. Other ATP/ADP IPT genes are barely detectable in vegetative organs (29). Therefore, we first made all combinations of double, triple, and quadruple mutants for AtIPT1, AtIPT3, AtIPT5, and AtIPT7. We also made multiple mutants that carried atipt6 for selected combinations. AtIPT6 was expressed mainly in the funiculus (data not shown). In the atipt 1 3 5 7 quadruple mutant, AtIPT4, AtIPT6, and AtIPT8, which are not normally expressed in the vegetative phase, were not ectopically expressed (Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

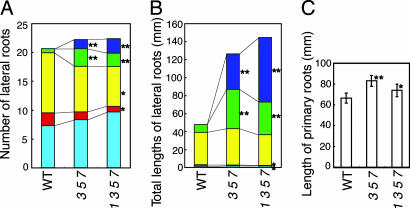

There were no visible phenotypes in double mutants of any possible mutant combination for AtIPT1, 3, 5, and 7. The atipt 3 5 7 triple mutant (data not shown), atipt3 5-1 6 7(data not shown) and the atipt1 3 5 7 quadruple mutants (Fig. 2B), and the atipt1 3 5-1 6 7 quintuple mutant (data not shown) had short, thin aerial parts, and the phenotype of the latter two lines tended to be more severe. Plants heterozygous for any one of atipt3, 5, and 7 and homozygous for the other two mutations appeared normal, indicating that the phenotype is closely linked to the mutations. The quadruple and quintuple AtIPT mutants were indistinguishable from wild type early on, but phenotypic differences become evident as they aged (Fig. 2 A and B). These mutants had fewer rosette leaves (Table 1), indicating a prolonged plastochron, appeared to have reduced shoot apical meristem size (Fig. 2 C and D), and had thin inflorescence stems. On vermiculite, flowering time was delayed in these multiple mutants; however, late flowering may be a secondary effect of reduced cytokinin production, because the flowering time was not delayed on nutrient agar. Some seeds were aborted, but surviving seeds were larger than those of the WT (data not shown). We also examined root growth in the atipt3 5 7 triple and the atipt1 3 5 7 quadruple mutants. Relative to wild type plants, both the number of lateral roots longer than 1 cm (Fig. 3A), and the total length of lateral roots (Fig. 3B) were increased in the triple and quadruple mutants. The primary roots of these mutants were slightly longer than those of the WT (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 2.

Phenotypes of atipt1 3 5 7. (A) Plants grown on vertical plates for 10 days. (B) Plants grown on nutrient-vermiculite for 39 days. (A and B Left) Col WT. (A and B Right) atipt1 3 5 7. (C and D) Shoot apical meristems in 5-day-old WT Columbia (C) and 5-day-old atipt1 3 5 7 (D). (Scale bars: A, 1 cm; B, 5 cm; C and D, 50 μm.)

Table 1.

Numbers of true leaves

| Line (n) | Number (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|

| WT(Col) (5) | 8.25 ± 0.41 |

| atipt3 5 7 (10) | 5.90 ± 0.32 |

| atipt1 3 5 7 (5) | 5.60 ± 0.55 |

Numbers of true leaves longer than 0.3 mm of 10-day-old plants were counted.

Fig. 3.

Enhanced root elongation in the atipt3 5 7 (3 5 7) and atipt1 3 5 7 (1 3 5 7) mutants. (A and B) Average number of lateral roots (A) and total length of lateral roots (B), with individual length ranges discriminated by color. (C) Primary root length. Values are mean ± SD. In A and B, light blue, 0–0.5 mm; red, 0.5–1.0 mm; yellow, 1.0–10.0 mm; green, 10.0–20.0 mm; blue, >20.0 mm. At least nine plants were used for a genotype. Single and double asterisks indicate significant difference between values of mutants and WT (0.01 < P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively).

We also made triple and quadruple mutants of other allele combinations (atipt1 5 6, atipt5 6 7, atipt1 3 5, atipt1 3 7, atipt1 5 7, atipt4 6 8, and atipt1 6 8, and quadruple mutants atipt1 3 5 6, atipt1 5 6 7, and atipt1 4 6 8). None of these mutants had a visible phenotype when grown on plates or on soil. These mutants possessed at least 1 WT AtIPT3, AtIPT5, or AtIPT7 gene, indicating that these three genes have redundant functions. atipt1 4 6 8 lacked all ATP/ADP IPTs that were preferentially expressed in reproductive organs or their associated tissues, but still set seeds normally (data not shown). Finally, we obtained mutants that lacked all 7 ATP/ADP IPTs (atipt1 3 4 5-1 6 7 8), which were thin and small, resembling the quadruple atipt1 3 5 7 mutant (data not shown).

Growth of Atipt Multiple Mutants Was Partially Rescued by tZ.

To determine whether the phenotypes of higher order mutants were the consequence of a decrease in endogenous cytokinin levels, we grew mutant plants in the presence of a cytokinin, tZ. In the absence of cytokinins, the atipt1 3 5 7 quadruple mutant had smaller aerial parts and longer lateral roots than WT (Fig. 4A), as described above. External application of tZ partially rescued the growth of aerial parts of the mutant (Fig. 4B; see Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), and reduced the numbers of elongated lateral roots in the mutant and WT. These results suggest that the growth defect is caused by cytokinin deficiency. Higher levels of tZ inhibited root and shoot growth of either genotype (data not shown), consistent with normal cytokinin responses.

Fig. 4.

Partial rescue of the atipt1 3 5 7 quadruple mutant by external application of cytokinin and complementation of the atipt3 5-1 6 7 mutant by AtIPT3 promoter::AtIPT3-GFP. (A and B) WT (Left) and atipt1 3 5 7 (Right) grown without (A) or with (B) 10 nM tZ for 21 days. (C Left) atipt3 5-1 6 7. (C Right) atipt3 5-1 6 7 carrying AtIPT3 promoter::AtIPT3-GFP. (D–G) Expression of AtIPT3 promoter::AtIPT3-GFP in WT root (D) or cotyledon (F), or in atipt3 5-1 6 7 root (E) or cotyledon (G). (Scale bars: A and B, 1 cm; C, 10 cm; D–G, 50 μm.)

AtIPT3-Promoter::AtIPT3-GFP Complements atipt3 5-1 6 7.

To confirm that the phenotypes of the atipt3 5-1 6 7 mutant are caused by mutations in these genes, we introduced AtIPT3-GFP driven by its native promoter (AtIPT3p::AtIPT3-GFP). The growth of atipt3 5-1 6 7 was completely recovered by AtIPT3p::AtIPT3-GFP, indicating that the atipt3 mutation was indeed one of the causes for the phenotypes of the quadruple mutant (Fig. 4C). The AtIPT3-GFP fluorescence patterns in WT and atipt3 5-1 6 7 were similar (Fig. 4 D–G), being located in the phloem, consistent with previous reports (29, 36). A punctate fluorescence pattern was present in the cells, which were previously reported to be plastids (36). These results indicate that the AtIPT3p::AtIPT3-GFP construct complemented the atipt3 5-1 6 7 mutant and was expressed in the same tissue with the same subcellular localization as in WT plants.

ATP/ADP IPTs Play a Crucial Role for Biosynthesis of iP-Type and tZ-Type Cytokinins.

We determined riboside, ribotide, and glucoside forms of cytokinins in WT Columbia, atipt1, atipt2, atipt3, atipt5, atipt7, and atipt9, and in double and triple mutants of selected combinations, and in the atipt1 3 5 7 quadruple mutant. All of these mutants are in the Columbia background. We also measured the levels of free-base cytokinins in selected lines (WT, atipt2, atipt 3 5 7, and atipt1 3 5 7) (Fig. 5). Similar to previous studies using cytokinin measurements, we could not discriminate between monophosphate and di- or triphosphate forms of cytokinins. Therefore, the values of isopentenyladenosine monophosphate (iPRMP) may represent the total pool of isopentenyl-AMP, isopentenyl-ADP, and isopentenyl-ATP present. Similarly, values of t-zeatin riboside monophosphate (tZRMP) might include tZRDP and tZRTP.

Fig. 5.

Cytokinin levels in AtIPT mutants. Values are mean ± SD of five samples. (A) iPRMP (black) and iPR (gray). (B) tZRMP (black) and tZR (gray). (C) cZRMP (black) and cZR (gray). (D) Free-base cytokinins: iP (black), tZ (gray), and cZ (open). (E) Glucosylated cytokinins: tZ7G (black), tZ9G (gray), and tZOG (open). Mutant names are shown as numbers (e.g., the atipt1 atipt3 double mutant is shown as 1 3).

In the single and double mutants carrying the atipt3 mutation, the levels of iPRMP and iPR were decreased (Fig. 5A), but decreases in the level of tZRMP or t-zeatin riboside (tZR) were less evident (Fig. 5B). In the atipt3 5 7 triple mutant and the atipt1 3 5 7 quadruple mutant, levels of iPRMP, iPR, tZRMP, tZR, tZ-7-glucoside (tZ7G), tZ-9-glucoside (tZ9G), and tZ-O-glucoside (tZOG) were all reduced to <20% of the WT values (Fig. 5A, B and D). The decreases in free-base iP and tZ in the atipt1 3 5 7 quadruple mutant were moderate compared with the decreases in the levels of riboside and ribotide forms (Fig. 5E). Interestingly, cZ, cis-zeatin riboside (cZR), and cis-zeatin riboside monophosphate (cZRMP) were increased in mutants that possessed decreased levels of iP-type and tZ-type cytokinins (Fig. 5C). These results indicate that cZ-type cytokinins are produced through a different pathway than iP- and tZ-type cytokinins, and suggest that degradation of cZ is under the negative regulation of cytokinin signaling.

tRNA IPTs Are Indispensable for Biosynthesis of cZ-Type Cytokinins.

Arabidopsis has two genes coding for tRNA IPT homologs, AtIPT2 and AtIPT9 (for review see refs. 3 and 20). Neither the atipt2-1 nor the atipt2-2 mutant showed a visible phenotype, but both the atipt9 single and the atipt2 9 double mutant often were chlorotic.

Levels of iP-type and tZ-type cytokinins were unaffected in atipt2, atipt9, or the atipt2 9 double mutant (Fig. 5 A, B, D, and E). By contrast, cZR and cZRMP were reduced in atipt2 and atipt9 (Fig. 5C). cZ was also reduced in atipt2 (Fig. 5D)(cZ was not examined in atipt9). cZR and cZRMP were undetectable in the atipt2 9 double mutant.

Because modified tRNA is a possible source of cZ, we examined cytokinin levels in dephosphorylated hydrolysate of tRNA (Table 2). WT tRNA contained iPR (0.074 ng/μg tRNA) and cZR (2.13 ng/μg tRNA), whereas tZR was under the detection limit of 0.25 pg/μg tRNA. Levels of iPR and cZR in tRNA samples were unchanged in the atipt1 3 5 7 quadruple mutant, indicating that ATP/ADP IPTs are not involved in isopentenylation of tRNA. Interestingly, in atipt2, the cZR-containing tRNA content was decreased to ≈30% of the WT level, whereas the iPR-containing tRNA level was unchanged. In contrast, in atipt9-1, the iPR-containing tRNA level was decreased to <4% of the WT level, whereas decreases in the cZR-containing tRNA level were moderate.

Table 2.

Cytokinins in tRNA

| Line | tZR | cZR | iPR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | ND | 2.13 ± 0.28 | 0.0740 ± 0.0113 |

| atipt2 | ND | 0.68 ± 0.10 | 0.0720 ± 0.0074 |

| atipt9 | ND | 1.36 ± 0.31 | 0.0027 ± 0.0006 |

| atipt 2 9 | ND | ND | ND |

| atipt1 3 5 7 | ND | 2.26 ± 0.37 | 0.0685 ± 0.0073 |

Measurements are nanograms of riboside equivalent per microgram of tRNA). tRNA was extracted from five different cultures per line. Cytokinin contents are shown as means ± SD. ND, below detection limits.

Discussion

In the atipt3 5 7 and the atipt1 3 5 7 mutants, levels of iP- and tZ-type cytokinins, including ribosides, ribotides, and glucosides, were greatly decreased, clearly indicating that ATP/ADP IPTs are critical for the formation of iP- and tZ-type cytokinins. These results provided compelling evidence that cytokinins are produced by plants, arguing against the hypothesis that cytokinins could be produced exclusively by microbial symbionts (37). Decreases in free-base cytokinins in the mutants, however, were less evident. Therefore, it is possible that conversion of riboside- and/or ribotide- cytokinins to free-base cytokinins is negatively regulated by cytokinin signaling, or that deactivation or degradation of free-base, riboside, and ribotide cytokinins are differentially regulated by cytokinin signaling. Interestingly, cZ-type cytokinin levels were inversely correlated with iP- and tZ-type cytokinin levels. This indicates that cZ-type cytokinins are produced by a different pathway than tZ- and iP-type cytokinins, and that cZ levels are regulated by cytokinin signaling.

In atipt1 3 5 7 seedlings, ectopic expression of the remaining ATP/ADP IPTs (AtIPT4, 6, and 8) was not detected. However, the quadruple mutant still possessed iP-type and tZ-type cytokinins. It is possible that these cytokinins are produced by AtIPT4, 6, and/or 8, although the undetectable expression of the corresponding transcripts for these AtIPTs in vegetative tissues argues against this hypothesis. It is possible that zeatin cis-trans isomerase, activity for which has been detected in Phaseolus vulgaris (38), produces tZ-type cytokinins from cZ-type cytokinins. However, if cis-trans isomerase activity is present in the quadruple mutant, the activity must be low because tZ-type cytokinin levels were greatly reduced compared with cZ-type cytokinin levels. It is also possible that degradation of tRNAs modified with a nonhydroxylated isopentenyl modification at the adenosine residue served as the source of low-levels of iP-type cytokinins, which would then be converted to tZ-type cytokinins. However, tRNA modification with a nonhydroxylated chain is minor compared with tRNA modification with a cis-hydroxylated side chain in Arabidopsis (Table 2).

None of the single and double mutants for ATP/ADP IPT genes exhibited a visible phenotype, and among the triple mutants, only atipt3 5 7 exhibited visible phenotypes. This redundancy was unexpected based on the unique expression patterns detected for the ATP/ADP IPTs. Furthermore, the AtIPT3p::AtIPT3-GFP fusion gene complemented the defects in the atipt3 5-1 6 7 quadruple mutant, although the transgene was expressed with a WT rather than ectopic expression pattern. This indicates that WT expression of AtIPT3 is sufficient to complement atipt3 5-1 6 7. Hence, whereas every ATP/ADP IPT exhibits a spatially specific expression pattern, these enzymes function redundantly in planta. The simplest explanation for this result is that cytokinins produced by AtIPT3 is translocated between tissues.

Among the single mutants for ATP/ADP IPTs, only the AtIPT3 mutant exhibited decreased levels of iP- and tZ-type cytokinins. The decreased cytokinin levels in atipt3 plants agree with a previous report in which nitrogen-induced accumulation of cytokinins was decreased in an atipt3 mutant (36). Because AtIPT3 is involved in nitrate-induced cytokinin increases (36), we grew atipt3 plants under nitrate-sufficient and nitrate-starved conditions. However, we found no visible phenotypic differences between atipt3 and wild type (data not shown) under either nutrient condition. A more detailed analysis of nitrate responses in the atipt3 mutant is necessary to understand the role of nitrate-induced cytokinin production.

Mutants lacking AtIPT3, 5, and 7 were severely inhibited in shoot growth, whereas lateral roots elongated more (Fig. 3). These phenotypes resembled those reported for cytokinin oxidase overexpressors, and agreed with previous experimental evidence that cytokinins positively regulate shoot elongation and negatively regulate root elongation (6, 7). However, a low level of cytokinin signaling is likely required for root growth, because growth of both roots and shoots was stunted in mutants lacking all cytokinin receptors (9, 39), and root growth was inhibited when a cytokinin oxidase gene was strongly expressed in roots after germination (5).

AtIPT2 and AtIPT9 resemble tRNA IPTs in their amino acid sequences (20, 23, 24), and AtIPT2 indeed suppresses the phenotypes of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant lacking a tRNA IPT (34). We measured cZR, tZR, and iPR contents in tRNA hydrolysates from WT and IPT mutants. Consistent with a previous report (30), a fraction of the tRNAs from WT plants possessed the isopentenyl side chain or the cis-hydroxylated isopentenyl side chain (Table 2). Levels of iPR- and cZR-containing tRNA were not affected in a quadruple mutant of genes representing all major ATP/ADP IPTs in the vegetative phase (atipt1 3 5 7) (Table 2), confirming that ATP/ADP IPTs were not involved in tRNA modification. In Sal. typhimurium, the isopentenyl chain of tRNA is hydroxylated at the cis position by the miaE product (35). Interestingly, in atipt2, the tRNA cZR level was decreased to ≈30% of WT, whereas the iPR level was unchanged. In contrast, in atipt9, the tRNA iPR level was decreased to <4% of WT levels, whereas the cZR level was only moderately decreased. Therefore it is possible that AtIPT2 transfers a cis-hydroxylated isopentenyl side chain to tRNA. However, in the Sac. cerevisiae mutant for tRNA IPT, AtIPT2 expression caused isopentenylation of tRNAs in yeast, but the side chain was not hydroxylated (34). To our knowledge, the predicted precursor for cZR-modified tRNA in Arabidopsis, cis-hydroxy dimethylallyl diphosphate (4-hydroxy-3-methyl-2-(Z)-butenyl diphosphate), has not been reported in any organism. Future work aimed at determining whether cis-hydroxyl dimethylallyl diphosphate exists in plants and Sac. cereviciae, and in which cellular compartment, will shed light on the mechanism for cZR-modification of tRNAs.

We showed that knockout mutants for either tRNA isopentenyltransferase in Arabidopsis, AtIPT2 or AtIPT9, possessed decreased levels of cZ-type cytokinins. This, combined with the fact that cZ-type cytokinins were undetectable in the atipt2 9 double mutant, clearly indicates that AtIPT2 and AtIPT9 are absolutely required for cZ-type cytokinin production (Fig. 5). The lack of detectable cZ in atipt2 9 also indicates that isomerization of tZ to cZ does not occur to a detectable level. The correlation between changes in tRNA modification and decreases in cZ-type cytokinin levels support the idea that cZ-type cytokinins are derived from modified tRNA.

In summary, our data indicate that iP- and tZ-type cytokinins are synthesized through the action of ATP/ADP IPTs, whereas cZ-type cytokinins are synthesized through the action of tRNA IPTs in planta. As Kamínek wrote (40), creation of tRNA-independent cytokinin biosynthetic route was probably an important event during evolution to higher plants, because it made precise regulation of cytokinin biosynthesis possible.

Materials and Methods

Plant Culture and Phenotypic Analysis.

Arabidopsis plants were grown on a solidified medium in plates or on vermiculite wetted with a nutrient solution. Detailed methods are provided at Supporting Materials and Methods, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site

Isolation of Atipt Mutants.

Plants containing the T-DNA insertion alleles of AtIPTs were obtained from Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (www.biosci.ohio-state.edu/∼plantbio/Facilities/abrc/abrchome.htm), the Kazusa DNA Research Institute (www.kazusa.or.jp/ja2003/english), or the Arabidopsis Knockout Facility at the University of Wisconsin. The ecotype of atipt1 (SALK_020112), atipt2-1 (SALK_042050), atipt2-2 (SALK_019906), atipt3-2 (KG21969), atipt5-2 (SALK_133407), atipt5-3 (SALK_136322), atipt7-1 (SALK_001940), and atipt9-1 (KG7770) is Columbia (Col). The ecotype of atipt4-1 (Wisconsin β 12), atipt4-2 (Wisconsin β 24), and atipt5-1 (Wisconsin α 6) is Wassilewskija (Ws). Genotypes were determined by PCR (see Supporting Materials and Methods).

Homologous Recombination.

Because we did not find T-DNA insertion mutants of AtIPT8, we targeted it by homologous recombination. The structure of the plasmid for gene targeting is described in Fig. 1. The genomic fragments of upstream (−4050 to +44) and downstream (+1,178 to +5,167) regions of AtIPT8 were amplified by PCR and inserted upstream or downstream of the 35S promoter::NPT2::35S-terminator in a binary vector. Primer sequences used for PCR are provided in the Supporting Materials and Methods. In ≈25,000 transformation events, we identified three homologous recombination events, and we used one of them for this study.

Complementation Analysis.

The genomic fragment encompassing 2.01 kbp of the AtIPT3 promoter was placed upstream of the entire coding region of AtIPT3 fused to GFP and cloned in a transformation vector. Then it was transformed into atipt3 5-1 6 7 by using Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Detailed methods are provided at Supporting Materials and Methods.

RT-PCR.

RNA samples were isolated from 10-day-old whole seedlings grown on plates. RT-PCR was performed as described in ref. 29. For primer sets used, see ref. 29 and Supporting Materials and Methods.

Cytokinin Measurements.

Eighteen-day-old Arabidopsis plate-grown plants were used for cytokinin measurements. For measurement of riboside, ribotide, and glucoside cytokinin levels, cytokinins were purified and derivatized according to Nordström et al. (41) with some modifications. For free-base cytokinins, cytokinins were purified according to Bieleski (42) with some modifications. For detail, see Supporting Materials and Methods. Cytokinins were quantified by liquid-chromatography-positive electrospray–tandem mass spectrometry in a multiple reaction-monitoring mode.

Purification of tRNA and Quantification of Cytokinins in tRNA.

tRNA was purified from 18-day old plate-grown Arabidopsis shoots, hydrolyzed and dephosphorylated according to Gray et al. (ref. 32 and references therein) with some modifications, and used for cytokinin analysis by using liquid chromatography-linked mass spectrometry (Supporting Materials and Methods).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Kusumoto for sampling and purification of cytokinins and Melissa Pischke for excellent critical reading, suggestions, and editing. T. Kakimoto was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research 15107001 (Japan Society for the Promotion of Science) and 17027017 (Ministry of Education, Sports, Science, and Technology), and Precursory Research for Embryonic Science and Technology, Japan Science and Technology. P.T. was supported by Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic Grant MSM 6198959216.

Abbreviations

- cZ

cis-zeatin

- cZR

cis-zeatin riboside

- iP

isopentenyladenine

- iPR

isopentenyladenosine

- tZ

trans-zeatin

- tZR

trans-zeatin riboside.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS direct submission.

References

- 1.Miller CO, Skoog F, von Saltza MH, Strong F. J Am Chem Soc. 1955;77:1392. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skoog F, Miller CO. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1957;11:118–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakakibara H. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:431–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mok MC. In: Cytokinins: Chemistry, Activity, and Function. Mok DWS, Mok MC, editors. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1994. pp. 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mähönen AP, Bishopp A, Higuchi M, Nieminen KM, Kinoshita K, Tormakangas K, Ikeda Y, Oka A, Kakimoto T, Helariutta Y. Science. 2006;311:94–98. doi: 10.1126/science.1118875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Werner T, Motyka V, Strnad M, Schmulling T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10487–10492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171304098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Werner T, Motyka V, Laucou V, Smets R, Van Onckelen H, Schmulling T. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2532–2550. doi: 10.1105/tpc.014928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riefler M, Novak O, Strnad M, Schmulling T. Plant Cell. 2006;18:40–54. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.037796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higuchi M, Pischke MS, Mähönen AP, Miyawaki K, Hashimoto Y, Seki M, Kobayashi M, Shinozaki K, Kato T, Tabata S, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8821–8826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402887101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuroha T, Ueguchi C, Sakakibara H, Satoh S. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005;47:234–243. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamada H, Suzuki T, Terada K, Takei K, Ishikawa K, Miwa K, Yamashino T, Mizuno T. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001;42:1017–1023. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romanov GA, Spichal L, Lomin SN, Strnad M, Schmulling T. Anal Biochem. 2005;347:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spichal L, Rakova NY, Riefler M, Mizuno T, Romanov GA, Strnad M, Schmulling T. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;45:1299–1305. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inoue T, Higuchi M, Hashimoto Y, Seki M, Kobayashi M, Kato T, Tabata S, Shinozaki K, Kakimoto T. Nature. 2001;409:1060–1063. doi: 10.1038/35059117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mähönen AP, Higuchi M, Tormakangas K, Miyawaki K, Pischke MS, Sussman MR, Helariutta Y, Kakimoto T. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1116–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mok DW, Mok MC. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2001;52:89–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emery RJ, Leport L, Barton JE, Turner NC, Atkins CA. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:1515–1523. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.4.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Kojima M, Yamaya T, Sakakibara H. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:1654–1661. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.037176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taya Y, Tanaka Y, Nishimura S. Nature. 1978;271:545–547. doi: 10.1038/271545a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kakimoto T. J Plant Res. 2003;116:233–239. doi: 10.1007/s10265-003-0095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akiyoshi DE, Klee H, Amasino RM, Nester EW, Gordon MP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:5994–5998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.19.5994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barry GF, Rogers SG, Fraley RT, Brand L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:4776–4780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.15.4776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kakimoto T. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001;42:677–685. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takei K, Sakakibara H, Sugiyama T. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:26405–26410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102130200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun J, Niu QW, Tarkowski P, Zheng B, Tarkowska D, Sandberg G, Chua NH, Zuo J. Plant Physiol. 2003;131:167–176. doi: 10.1104/pp.011494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakakibara H, Kasahara H, Ueda N, Kojima M, Takei K, Hishiyama S, Asami T, Okada K, Kamiya Y, Yamaya T, Yamaguchi S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9972–9977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500793102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takei K, Yamaya T, Sakakibara H. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41866–41872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Astot C, Dolezal K, Nordström A, Wang Q, Kunkel T, Moritz T, Chua NH, Sandberg G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14778–14783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.260504097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyawaki K, Matsumoto-Kitano M, Kakimoto T. Plant J. 2004;37:128–138. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taller BJ. In: Cytokinins: Chemistry, Activity, and Function. Mok DWS, Mok MC, editors. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1994. pp. 101–112. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koenig RL, Morris RO, Polacco JC. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:1832–1842. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.7.1832-1842.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gray J, Gelvin SB, Meilan R, Morris RO. Plant Physiol. 1996;110:431–438. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.2.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bjork GR. tRNA. Washington, DC: Am Soc Microbiol; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Golovko A, Sitbon F, Tillberg E, Nicander B. Plant Mol Biol. 2002;49:161–169. doi: 10.1023/a:1014958816241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Persson BC, Bjork GR. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7776–7785. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7776-7785.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takei K, Ueda N, Aoki K, Kuromori T, Hirayama T, Shinozaki K, Yamaya T, Sakakibara H. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;45:1053–1062. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holland MA. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:865–868. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.3.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bassil NV, Mok D, Mok MC. Plant Physiol. 1993;102:867–872. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.3.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishimura C, Ohashi Y, Sato S, Kato T, Tabata S, Ueguchi C. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1365–1377. doi: 10.1105/tpc.021477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaminek M. J Theor Biol. 1974;48:489–492. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(74)80018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nordström A, Tarkowski P, Tarkowska D, Dolezal K, Astot C, Sandberg G, Moritz T. Anal Chem. 2004;76:2869–2877. doi: 10.1021/ac0499017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bieleski RL. Anal Biochem. 1964;9:431–442. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(64)90204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.