Abstract

Objectives

To compare the power of three traditional selection procedures (A levels, personal statements, and references) and one non-traditional selection procedure (personality) to predict performance over the five years of a medical degree.

Design

Cohort study over five years.

Setting

Nottingham medical school.

Participants

Entrants in 1995.

Main outcome measures

A level grades, amounts of information contained in teacher's reference and the student's personal statement, and personality scores examined in relation to 18 different assessments.

Results

Information in the teacher's reference did not consistently predict performance. Information in the personal statement was predictive of clinical aspects of training, whereas A level grades primarily predicted preclinical performance. The personality domain of conscientiousness was consistently the best predictor across the course. A structural model indicated that conscientiousness was positively related to A level grades and preclinical performance but was negatively related to clinical grades.

Conclusion

A teacher's reference is of no practical use in predicting clinical performance of medical students, in contrast to the amount of information contained in the personal statement. Therefore, simple quantification of the personal statement should aid selection. Personality factors, in particular conscientiousness, need to be considered and integrated into selection procedures.

Introduction

A recent review of published research of predictors of performance of students at medical school highlighted several issues requiring further study.1 Specifically the relative contribution of references, personal statements, and personality traits to predict performance across the medical degree has not been examined in single study. Work that has been conducted on each of these factors is consistent with studies in other occupations.2 It shows that references do not predict performance; the value of personal statements is mixed, and the personality domain of conscientiousness predicts preclinical performance but not performance as qualified general practitioners.3–5

We examined the role of four variables (A levels, the applicant's personal statement, the teacher's reference, and personality) in all stages of undergraduate medical training. We also examined how these variables are interrelated with performance by using a structural equation.6,7

Personality domains of the big five8

Emotional stability—high scores equate to being relaxed and unemotional (mean score 43.1 (SD 8.4), Cronbach's α=0.79)

Surgency—high scores equate to extroversion (44.4 (7.7), 0.82)

Intellect—high scores equate to being creative, reflective, and imaginative (47.2 (6.6), 0.71)

Agreeableness—high scores equate to cooperativeness (49.3 (5.8), 0.74)

Conscientiousness—high scores equate to being hardworking and organised (45.5 (9.1), 0.86)

Methods

We followed the 1995 entry cohort at Nottingham medical school over the five years of training. The mean age of the 176 entrants was 19.7 (SD 2.11) years (range 18-35). Of these, 102 (58%) were women. We coded the students' A level grades and the contents of their UCAS personal statements and their references. Two and a half years into the course, 67% of the original cohort gave consent for their personality scores to be assessed. We recorded the performance of the students in 18 formal assessments over the preclinical (years 1 and 2; four assessments), BMedSci (year 3; four assessments), and clinical (years 4 and 5; 10 assessments) components of the course.

Measures

A level points score

Overall, 86% of the students had taken A levels. We recorded points scores for A levels for each student (10 points for A grade, 8 for B grade, 6 for C grade, 4 for D grade, and 2 for E grade).

Personal statement and reference coding

We analysed the content of the free response personal statement and reference in the student's UCAS application form by using manifest coding.w2 w3 Most of the personal statement categories covered motivation and hobbies whereas the reference categories covered character and social skills. See bmj.com for details of the coding scheme and procedures.

Personality

We used Goldberg's bipolar adjectives to measure the “big five” domains for personality (see box).8

Outcome measures

Overall, four themes are recorded for the preclinical years: A (the cell: mean score 65.3%, range 50-80%), B (the person: 61.4%, 61-80%), C (the community: 65.7%, 49-86%), and D (the doctor—personal and professional development: 63%, 42-86%).

Four assessments make up the BMedSci year: marks for a project (mean score 65.3%, range 36-85%), a viva voce (65.3%, 30-90%), a data analysis paper (64.2%, 48-82%), and a theoretical paper (53%, 6-74%).

We made 10 assessments during the clinical years. Seven of these were scored as a grade and converted by standard α numeric conversion: D=0, C=1, B=2, and A=3.9–11 The results of these clinical assessments comprised junior surgery (median grade 2, range 1-3), junior medicine (2, 1-3), psychiatry (2, 0-3), obstetrics and gynaecology (2, 0-3), dermatology (mean score 73.6%, range 46-86%), child health (median grade 2, range 0-3), general practice (2, 1-3), ophthalmology (mean score 55%, range 27-83%), ear, nose, and throat (50%, 28-75%), and senior medicine and surgery (60%, 43-77%). We calculated the average scores for the main course components by summing the four preclinical assessments, the four BMedSci assessments, and the 10 clinical assessments.

Analyses

We analysed the data with a mixture of univariate (zero order correlations, t test, χ2 test) and multivariate methods (multivariate analysis of variance; hierarchical multiple linear regression, and structural equations modelling).12 w4 w5 See bmj.com for details on the structural modelling.

Results

Potential sampling bias

Students who completed the personality questionnaire did not differ significantly from those who did not for age (t1,173=1.1, P=0.27), sex (χ2=3.06 (df=1), P=0.08), preclinical, BMedSci, and clinical performance (multivariate F3,140=0.007, P=0.79), and whether or not they obtained honours (χ2=1.6 (df=1), P=0.20).

Univariate analyses

Table 1 shows the zero order correlations (Pearson's r) between each of the predictors and each of the 18 assessments. Better A level grades significantly predicted better performance in six of the 18 assessments (33%). Three of these six assessments were the preclinical marks (themes A, B, and C).

Table 1.

Zero order bivariate associations between predictors and outcomes

| Predictor

|

Medical assessments

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preclinical

|

BMedSci

|

Clinical

|

||||||||||||||||||

| A

|

B

|

C

|

D

|

Empirical project

|

Viva voce

|

Analytical paper

|

Theory paper

|

Junior surgery

|

Senior surgery

|

Junior medicine

|

Child health

|

General practice

|

Psychiatry

|

Obstetrics and gynaecology

|

Ophthalmics

|

Dermatology

|

Ear, nose, and throat

|

|||

| Information in reference | −0.02 | −0.08 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0 | 0.09 | −0.10 | −0.06 | −0.11 | 0.08 | 0.17* | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.09 | −0.02 | −0.07 | −0.07 | ||

| Information in personal statement | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.14* | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.09 | 0.09 | −0.19* | 0.16* | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.14* | 0.18* | 0.18* | 0.09 | ||

| Previous academic performance | 0.40* | 0.32* | 0.30* | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.19* | −0.02 | 0.19* | 0.06 | 0.04 | −0.09 | 0.05 | 0.24* | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.08 | ||

| Emotional stability | 0.09 | 0.15* | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.17* | 0.25* | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.11 | −0.06 | 0 | 0 | 0.11 | 0 | 0.12 | ||

| Surgency | −0.10 | −0.16* | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.07 | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.21* | 0.14 | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0 | −0.23* | 0.13 | −0.11 | ||

| Intellect | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.10 | −0.02 | −0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | −0.05 | 0.16* | 0.00 | −0.12 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.01 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.03 | ||

| Agreeableness | 0.16* | 0.13 | 0.24* | 0.23* | 0.16* | 0.28* | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0 | 0.27* | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.01 | ||

| Conscientiousness | 0.46* | 0.47* | 0.49* | 0.38* | 0.30* | 0.38* | 0.25* | 0.33* | 0.08 | 0.28* | 0.04 | 0.18* | 0.17* | 0.15 | 0.21* | 0.17* | 0.17* | 0.15 | ||

P⩽0.05, **P<0.01 (range 104-175).

More information in the personal statement was predictive of 33% of the assessments and specifically better clinical performance (theme D, junior surgery, senior surgery, obstetrics and gynaecology, ophthalmology, and dermatology). Higher scores on conscientiousness were significantly related to better performance across most (78%) of the assessments. Students scoring higher on agreeableness performed better on 33% of the assessments. Those scoring higher on emotional stability or lower on surgency performed better on 17% of the assessments. Finally, the amount of information in the reference and scores on intellect were both correlated with 0.055% of the assessments (chance level).

Multivariate analyses

To examine the relative predictive power of the traditional and non-traditional predictors for preclinical, BMedSci, or clinical performance, we conducted a series of three hierarchical multiple linear regression analyses. The traditional selection measures were entered at step 1 and personality at step 2 (table 2).

Table 2.

Hierarchical multiple linear regression analyses for predictors and aggregate outcome measures

| Source of information

|

Preclinical

|

BMedSci

|

Clinical

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Previous academic performance | 0.39*** | 0.34** | 0.32** |

| Information in personal statement | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.23* |

| Information in reference | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.14 |

| R2† | 0.18*** | 0.13* | 0.15** |

| Emotional stability | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0 |

| Surgency | −0.11 | −0.13 | −0.26* |

| Intellect | 0.01 | 0 | 0.03 |

| Agreeableness | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| Conscientiousness | 0.58*** | 0.57*** | 0.26* |

| R2 | 0.51*** | 0.47*** | 0.28* |

| Change in R2 | 0.33*** | 0.33*** | 0.13* |

| No of students | 89 | 85 | 81 |

P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Variance accounted for (range 0-1).

A level points predicted assessment scores across the course. The amount of information contained within the personal statement was a significant predictor of clinical performance. The addition of the personality scores significantly improved the fit of the regression models. Conscientiousness was the only personality variable that showed a consistent pattern of significant effects across all three general assessments.

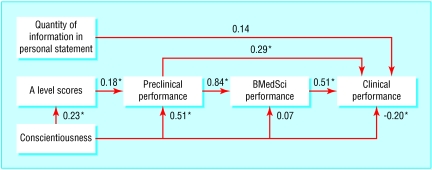

Model fitting

The figure presents the best fitting structural model (χ2=5.82, df=6), P=0.44, comparative fit index=1.0, root mean square approximation of error=0.0 (90% confidence interval 0 to 0.14), n=87). Higher scores on the preclinical assessments significantly predicted better clinical performance. Higher scores on A levels were directly related to better preclinical performance. Higher scores for conscientiousness were significantly correlated with better A level scores and related to better scores on preclinical assessments and to worse performance on clinical assessments.

Discussion

The amount of information contained in a teacher's reference does not reliably predict performance of a student at medical school. A level scores were a good predictor of performance, and the amount of information in the personal statements related to clinical performance. The personality domain of conscientiousness showed the most consistent pattern of significant relations with the outcome measures, a finding that is consistent with results reported for other occupations.13 The structural model indicated that those scoring high for conscientiousness were more likely to have better A levels grades and to do better on preclinical assessments but less well in clinical assessments. It may be that the behaviours (for example, organised, methodical) associated with high scores for conscientiousness are more suited to the factual nature of preclinical learning; which in turn is related to better clinical performance. Once any benefit from preclinical learning has been accounted for, these same behaviours may, however, be less well suited to clinical learning, such as strategic problem solving. Practically, our results suggest a combination of A level scores, an index of the amount of information in the personal statement, and scores for conscientiousness could aid selection for interview.

Limitations

The small sample size limits the statistical power of our study, and this may account for null results seen for the reference. However, the findings reported for the reference are consistent with previous work.1,2 That the results are based on a single cohort may introduce sample bias and limit the generalisability of our findings. The effects of conscientiousness, however, are consistent with a large body of findings outside medicine and a small, but growing, body of findings reported in medicine.3,4,13 Indeed, we see our study as a pilot investigation, and we are currently following a second cohort, where the results show conscientiousness as the main personality predictor of preclinical performance (data not shown).

Supplementary Material

Figure.

Best fitting structural model (*P<0.05)

Acknowledgments

We thank Jane Schroeder for additional help with data input.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

References

- 1.Ferguson E, James D, Maddeley L. Factors associated with success in medical school and in a medical career. BMJ. 2002;324:952–957. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7343.952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson N, Shackleton V. Successful selection interviewing. Oxford: Blackwell; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferguson E, Sanders A, O'Hehir F, James D. Predictive validity of personal statement and the role of the five factor model of personality in relation to medical training. J Occ Org Psychol. 2000;73:321–344. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ievens F, Coetsier P, De Fruty F, De Maeseneer J. Medical students' personality characteristics and academic performance: a five-factor model perspective. Med Educ. 2002;36:1050–1056. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Patterson F, Ferguson E, Lane P, Norfolk T. A new competency based selection system for general practitioners. Paper presented as part of a symposium on personality and medicine. The 10th international conference of the International Society for the Study of Individual Differences. Edinburgh, Scotland, 7-11 Jul, 2001.

- 6.McManus IC, Richards P. Admission for medicine in the United Kingdom: a structural model of background factors. Med Educ. 1986;20:181–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1986.tb01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McManus IC, Maitlis SL, Richards P. Shortlisting of applicants from UCCA forms: the structure of pre-selection judgements. Med Educ. 1989;23:136–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1989.tb00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg LR. The development of markers for the big-five factor structure. Psychol Assess. 1992;4:26–42. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones B. Can trait anxiety, grades, and test scores measured prior to medical school matriculation predict clerkship performance? Acad Med. 1991;66:S22–S24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall ML, Stocks MT. Relationship between quantity of undergraduate science preparation and preclinical performance in medical school. Acad Med. 1995;70:230–235. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199503000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McManus IC, Richards P, Winder BC. Intercalated degrees, learning styles, and career preferences: prospective longitudinal study of UK medical students. BMJ. 1999;319:542–546. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7209.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analyses for the behavioral sciences. London: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tett R, Jackson D, Rothstien M. Personality measures as predictors of job performance: a meta-analytic review. Personnel Psychol. 1991;44:703–742. [Google Scholar]