Abstract

A major catabolic pathway for the gibberellins (GAs) is initiated by 2β-hydroxylation, a reaction catalyzed by 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. To isolate a GA 2β-hydroxylase cDNA clone we used functional screening of a cDNA library from developing cotyledons of runner bean (Phaseolus coccineus L.) with a highly sensitive tritium-release assay for enzyme activity. The encoded protein, obtained by heterologous expression in Escherichia coli, converted GA9 to GA51 (2β-hydroxyGA9) and GA51-catabolite, the latter produced from GA51 by further oxidation at C-2. The enzyme thus is multifunctional and is best described as a GA 2-oxidase. The recombinant enzyme also 2β-hydroxylated other C19-GAs, although only GA9 and GA4 were converted to the corresponding catabolites. Three related cDNAs, corresponding to gene sequences present in Arabidopsis thaliana databases, also encoded functional GA 2-oxidases. Transcripts for two of the Arabidopsis genes were abundant in upper stems, flowers, and siliques, but the third transcript was not detected by Northern analysis. Transcript abundance for the two most highly expressed genes was lower in apices of the GA-deficient ga1–2 mutant of Arabidopsis than in wild-type plants and increased after treatment of the mutant with GA3. This up-regulation of GA 2-oxidase gene expression by GA contrasts GA-induced down-regulation of genes encoding the biosynthetic enzymes GA 20-oxidase and GA 3β-hydroxylase. These mechanisms would serve to maintain the concentrations of biologically active GAs in plant tissues.

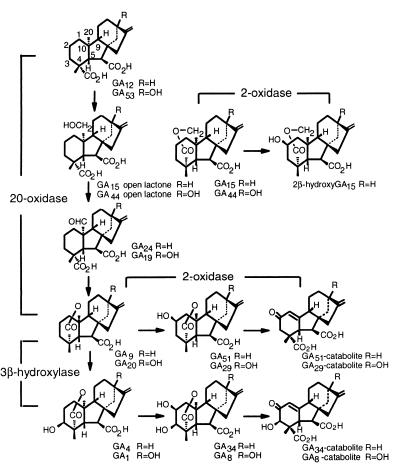

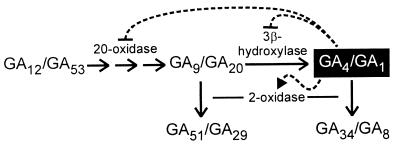

The gibberellins (GAs) form a large group of tetracyclic diterpenoid carboxylic acids, certain members of which function as natural regulators of growth and development throughout the life cycle of higher plants (1). The biologically active compounds, such as GA1 (Fig. 1), are produced from trans-geranylgeranyl diphosphate by the sequential action of cyclases, membrane-associated monooxygenases, and soluble 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases (2). The dioxygenases catalyze the later steps in the pathway, including the removal of C-20 (by GA 20-oxidase) and the introduction of the 3β-hydroxyl group (by GA 3β-hydroxylase; see Fig. 1). A third dioxygenase introduces a 2β-hydroxyl group, resulting in biologically inactive products that cannot be converted to active forms. In recent years, cDNA and genomic clones encoding GA-biosynthetic enzymes have been isolated from many species (reviewed in refs. 2 and 3). The availability of these clones has resulted in new insights into the regulation of GA biosynthesis. For example, it was shown that GA 20-oxidases are encoded by several genes that are differentially regulated throughout plant development (4, 5). Although GA 2β-hydroxylases play an important role in determining the concentration of bioactive GAs, the genes for these enzymes have not yet been isolated and it has not been possible to study their regulation.

Figure 1.

Pathways of GA biosynthesis and deactivation, showing reactions catalyzed by 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases.

Gibberellin 2β-hydroxylase activity is abundant in seeds during the later stages of maturation, particularly in legume seeds, which accumulate large amounts of 2β-hydroxylated GAs (6–8). Indeed, GA8, the first 2β-hydroxyGA to be identified, was extracted from seeds of runner bean (Phaseolus coccineus, originally classified as P. multiflorus) (9). In certain species, including legumes, further metabolism of 2β-hydroxyGAs occurs to form the so-called catabolites, e.g. GA51-catabolite in Fig. 1, in which C-2 is oxidized to a ketone and the lactone is opened with the formation of a double bond between C-10 and an adjacent C atom (6, 10).

Despite attempts to purify GA 2β-hydroxylases from cotyledons of pea (Pisum sativum) (11) and French bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) (12, 13), it was not possible to obtain sufficient purified protein for full characterization. However, these studies confirmed earlier work with cell-free extracts of seed tissues (14, 15) that showed that the GA 2β-hydroxylases were 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. In the present paper, we describe the use of a functional screening method, similar to that described by Lange (16), to isolate from P. coccineus seeds the first cDNA clone encoding a GA 2β-hydroxylase. The DNA sequence of the cDNA has enabled us to obtain three further GA 2β-hydroxylase cDNAs from Arabidopsis thaliana. Functional analysis of the recombinant proteins, obtained by expression of the cDNAs in Escherichia coli, indicates that at least some of these enzymes are multifunctional, catalyzing the formation of both 2β-hydroxyGAs and their catabolites. Therefore, to encompass this multifunctionality, we propose that the enzymes be referred to as GA 2-oxidases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material.

Runner bean (P. coccineus L.) was grown in the field. After removing the testae from late-developing seeds [2–3 g fresh weight per embryo, containing approximately 43% (wt/wt) dry matter], the embryos were frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C. The Columbia strain and the ga1–2 mutant of A. thaliana Heynh. (L.), were grown as described (5).

Functional Screening.

RNA was extracted from P. coccineus embryos according to Verwoerd et al. (17). Poly(A)+ mRNA (5 μg), purified by chromatography on oligo(dT) cellulose, was used for the construction of a cDNA library of 1 × 106 recombinant clones in λ-ZAPII by using the ZAP cDNA synthesis kit (Stratagene). A phagemid stock was prepared by using 1 × 109 plaque-forming units of the amplified cDNA library according to the manufacturer’s in vivo excision protocol (Stratagene). For the primary screen, E. coli SOLR were infected with the phagemid stock, resulting in approximately 11,000 colony-forming units. These were divided between the 48 wells (6 × 8 array) of a microtiter plate and amplified by overnight growth at 37°C with shaking, in 0.5 ml of 2× YT broth (0.8% tryptone/0.5% yeast extract/0.25% NaCl) supplemented with 50 mg/liter kanamycin and 100 mg/liter carbenicillin. Aliquots (20 μl) from the wells in each row and column were combined to make 14 pools, each of which was added to 10 ml of the same medium with antibiotics and grown at 37°C with shaking until an OD at 600 nm of 0.2–0.5 was reached. Expression of fusion protein then was induced by the addition of isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside to 1 mM and incubating for 16 h at 30°C with shaking. The bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in 0.75 ml of 100 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5/5 mM DTT. Bacteria were lysed by sonication, and the cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation.

The supernatants were assayed for GA 2β-hydroxylase activity as described below, revealing activity from pooled bacteria in row 6 (R6) and column 1 (C1). For the secondary screen, bacteria from well R6C1 were plated out on 2× YT agar with the antibiotics above and grown for 16 h at 37°C. One hundred colonies were picked at random and each was transferred to 5 ml 2× YT broth with antibiotics and grown, with shaking, for 16 h at 37°C. The cultures were arranged in a 10 × 10 grid, and pools from each row and column were induced as above and tested for GA 2β-hydroxylase activity as described below, indicating that cultures R2C7 and R9C10 were expressing GA 2β-hydroxylases.

Enzyme Assays.

GA 2β-hydroxylase activity was determined by measuring the release of 3H2O from a [2β-3H]GA, as described by Smith and MacMillan (13). Bacterial lysate (different volumes) was incubated for 1 h at 30°C with ∼50,000 dpm [1β, 2β-3H2]GA4 (1.24 × 1015 Bq/mol; Amersham) or [2β, 3β-3H2]GA9 (1.74 × 1015 Bq/mol; gift from Alan Crozier, University of Glasgow, U.K.), in the presence of 100 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5/4 mM 2-oxoglutarate/0.5 mM FeSO4/4 mM ascorbate/4 mM DTT/1 mg/ml catalase/2 mg/ml BSA, in a final reaction volume of 100 μl. Tritiated GAs then were removed by the addition of 1 ml of a suspension of activated charcoal in water (5% wt/vol) and centrifugation for 5 min in a microcentrifuge. Radioactivity was determined in aliquots (0.5 ml) of the supernatant by liquid scintillation counting.

To confirm the function of the cDNA expression products, bacterial lysate was incubated for 2.5 h with [17-14C]GAs (obtained from L. N. Mander, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia) in the presence of cofactors, as described above. After the incubation, acetic acid (10 μl) and water at pH 3 (140 μl) were added, and the mixture was centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was analyzed by HPLC with on-line radiomonitoring and products identified by combined GC/MS, as described previously (18). [17-14C]GA51 was prepared by incubating [17-14C]GA9 with PcGA2ox1, and the open lactone of [17-14C]GA15 was obtained from [17-14C]GA15 by base hydrolysis, as described previously (14).

PCRs.

The predicted protein sequence of PcGA2ox1 was used to search the Genomic Survey Sequences database at the National Centre for Biological Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) by using the tblastn program. Two Arabidopsis partial genomic sequences, T3M9-Sp6 and T24E24TF, demonstrated high amino acid sequence identity with PcGA2ox1. Oligonucleotide primers were designed based on the T3M9-Sp6 (sense, 5′-TAATCACTATCCACCATGTC-3′; antisense, 5′-TGGAGAGAGTCACCCACGTT) and T24E24TF (sense, 5′-GGTTATGACTAACGGGAGGT-3′; antisense, 5′-CTTGTAAGCAGAAGATTTGT-3′) genomic sequences and used in PCR with Arabidopsis genomic DNA, obtained as described previously (5), as a template. The PCR contained 200 ng genomic DNA, 1× PCR buffer (Promega), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dNTP, 1 μM each primer, and 2 units of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega) in 50 μl. The reactions were heated to 94°C for 3 min, and then 35 cycles of amplification were performed (94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s) followed by a final 10-min incubation at 72°C. Resulting PCR products were cloned into the pCR2.1 vector by using the TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) and sequenced. The clones derived from T3M9-Sp6 and T24E24TF were designated as AtT3 and AtT24, respectively.

A third Arabidopsis full-length genomic sequence, T31E10.11, with a high amino acid identity with PcGA2ox1, was detected in the GenBank database. A full-length cDNA clone (AtGA2ox3) was obtained by PCR from cDNA derived from Arabidopsis inflorescences as described below. PCR was as described above by using oligonucleotide primers: sense, 5′-TAGAATTCGACCATGGTAATTGTGTTACAGC-3′; and antisense, 5′-GCCTCGAGTCAAACATTGGATAGAGAGAAAATG-3′.

Northern Blot Analysis and Screening of Arabidopsis cDNA Library.

Poly(A)+ RNA was extracted as described above from siliques, flowers, upper stems (the top 2 cm of stem), lower stems, leaves (cauline and rosette), and roots of the Columbia ecotype of Arabidopsis. Northern blots were prepared by electrophoresis of the mRNA (5 μg) through agarose gels containing formaldehyde and transfer to nitrocellulose (19). Random-primed 32P-labeled probes were generated by using Ready-To-Go labeling beads (Pharmacia). Hybridizations were carried out in the presence of 50% formamide at 42°C for 16 h [hybridization buffer: 5× SSPE (0.18 M NaCl/10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4/1 mM EDTA)/2× Denhardt’s (0.02% polyvinylpyrrolidone/0.02% Ficoll/0.02% BSA)/0.5% SDS/0.01% denatured sonicated salmon sperm DNA/10% dextran sulfate]. Blots were washed twice for 10 min in 1× SSC/0.5% SDS at 20°C. Two further 10-min washes were performed in 0.1× SSC/0.5% SDS at 60°C. Blots were exposed to Kodak MS film at −80°C with MS-intensifying screens.

A cDNA library was constructed by using 5 μg of inflorescence poly(A)+ mRNA as described above. A total of 5 × 105 recombinant phage in E. coli XL1-Blue MRF′ were plated on five 24 × 24-cm plates. Plaques were grown until confluent (8–10 h), and then duplicate lifts were taken on supported nitrocellulose filters (Nitropure; Micron Separations) and processed (19). Hybridization of 32P-labeled AtT3 and AtT24 probes was performed as described above. Positive plaques were rescreened until plaque-pure clones were isolated. Plasmid rescue was performed by using Stratagene’s Rapid Excision kit. The cDNA clones were sequenced and recombinant protein was expressed in E. coli and tested for GA 2β-hydroxylase activity as described above.

DNA Sequencing.

Plasmid DNA, isolated by using the Promega Wizard Plus SV miniprep kit, was sequenced by using Amersham’s Taq cycle sequencing kit on an Applied Biosystems 377 automated sequencer. Sequence analysis was performed by using the program sequencher 3.0 from Gene Codes (Ann Arbor, MI), and alignments were displayed by using the program genedoc (http://www.cris.com/∼Ketchup/genedoc.shtml).

RESULTS

Isolation of a GA 2-Oxidase cDNA from P. coccineus Seed.

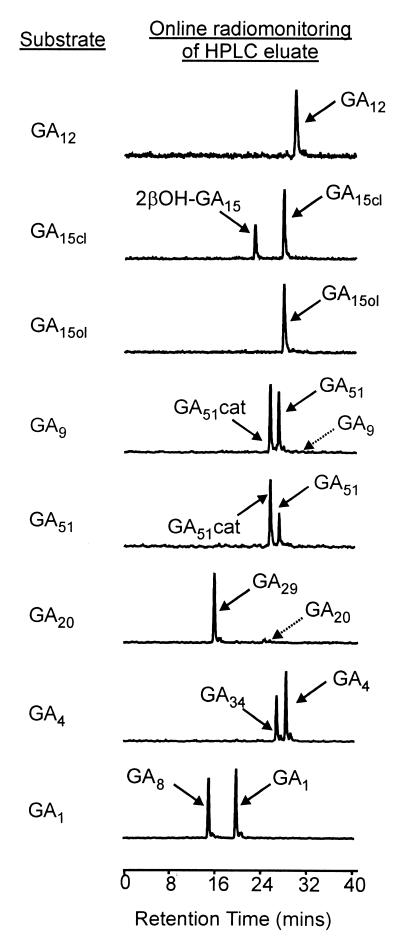

An amplified cDNA library in λZAPII was prepared by using poly(A)+ RNA from developing embryos of P. coccineus. E. coli infected with the phagemid stock obtained from this library was divided between 48 wells of a microtiter plate arranged in a 6 × 8 array. Cell lysates from bacteria pooled from rows and columns of this grid were assayed in the presence of dioxygenase cofactors for the release of tritium from [2β, 3β-3H2]GA9, allowing activity to be identified in a single pool. The lysate from this pool also released tritium from [1β, 2β-3H2]GA4, indicating the presence of GA 2β-hydroxylase activity. In a secondary screen, bacteria from the active pool were plated out and 100 colonies were selected at random and cultured in a 10 × 10 array. Assay of lysates from pooled columns and rows allowed the identification of two cultures capable of 2β-hydroxylase activity, one of which was investigated further. A cell lysate from this culture converted [17-14C]GA9 to two radioactive products (Fig. 2), which were identified by GC/MS as 14C-labeled GA51 and GA51-catabolite.

Figure 2.

Radiochromatograms showing separation by HPLC of 14C-labeled GA substrates and products after incubation with recombinant PcGA2ox1. GA15cl and GA15ol refer, respectively, to the closed- and open-lactone forms of GA15. Products were identified as methyl esters trimethylsilyl ethers by GC/MS by comparison of their mass spectra with published spectra (27): putative [17-14C]2β-hydroxyGA15 mass/charge (% relative abundance), 434(72), 419(12), 402(21), 376(16), 312(33), 284(100), 256(31), 239(94), 195(41), 157(91); [17-14C]GA51, 420(3), 388(19), 330(19), 298(19), 286(80), 284(28), 243(27), 229(39), 227(100), 226(58), 143(33); [17-14C]GA51-catabolite (as enol), 432(100), 417(5), 373(18), 357(13), 313(49), 283(18), 269(20); [17-14C]GA29, 508(100), 493(8), 479(6), 449(8), 391(11), 377(8), 305(29), 237(8), 209(37); [17-14C]GA34, 508(100), 418(9), 374(6), 358(5), 313(10), 290(16), 263(11), 231(22), 225(21), 217(32), 203(21), 147(31); [17-14C]GA34-catabolite (as ketone), 448(39), 389(19), 373(52), 329(100), 313(66), 299(22), 260(30), 239(51), 201(68) (from a different set of incubations); [17-14C]GA8, 596(100), 594 (78), 581(7), 579(5), 537(8), 450(20), 448(17), 381(9), 379(13), 377(13), 313(8), 283(11), 240(15), 238(15), 209(30), 207(28).

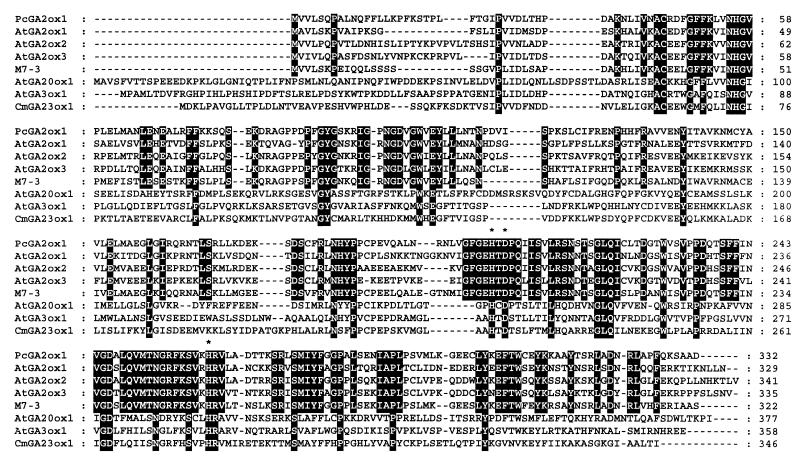

The cDNA was designated PcGA2ox1 according to nomenclature used by Coles et al. (20). It contained an ORF of 993 bp, encoding a protein of 331 aa, with a Mr of 37,200. Alignment of the amino acid sequence with those of other dioxygenases of GA biosynthesis (Fig. 3) confirmed that it belonged to the same class of enzyme, containing the sequences that are conserved within the class, including the His-204, Asp-206, and His-261 (numbers refer to PcGA2ox1 sequence) that, by analogy with the related enzyme cephalosporin synthase (21), bind Fe at the active site. The 2-oxidase amino acid sequence had the most similarity to GA 3β-hydroxylase sequences, although the degree of similarity is only slightly higher than with other dioxygenase sequences (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Alignment of deduced amino acid sequences of GA 2-oxidases and other dioxygenases of GA biosynthesis. Dark shading indicates amino acid residues that are conserved in the GA 2-oxidases. ∗, Amino acid residues presumed to bind Fe at the active site. M7–3, putative dioxygenase of undefined function from M. macrocarpus (accession no. Y09113); AtGA20ox1, GA 20-oxidase from Arabidopsis encoded by the GA5 gene (accession no. X83379); AtGA3ox1, GA 3β-hydroxylase from Arabidopsis encoded by the GA4 gene (accession no. L37126); CmGA23ox1, GA 2β, 3β-dihydroxylase from pumpkin (accession no. U63650).

Table 1.

Amino acid sequence homology between GA 2-oxidase and other dioxygenases of GA biosynthesis

| No. | Pc2ox1

|

At2ox1

|

At2ox2

|

At2ox3

|

M7-3

|

At20ox1

|

At3ox1

|

Cm2,3ox1

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | #2 | #3 | #4 | #5 | #6 | #7 | #8 | |

| 1 | — | 53 | 59 | 54 | 63 | 21 | 26 | 24 |

| 2 | 71 | — | 52 | 49 | 58 | 23 | 23 | 22 |

| 3 | 73 | 71 | — | 68 | 53 | 21 | 27 | 25 |

| 4 | 68 | 68 | 84 | — | 50 | 21 | 25 | 23 |

| 5 | 78 | 73 | 70 | 68 | — | 21 | 25 | 23 |

| 6 | 38 | 40 | 40 | 38 | 40 | — | 25 | 20 |

| 7 | 44 | 42 | 44 | 41 | 43 | 42 | — | 33 |

| 8 | 40 | 37 | 41 | 41 | 42 | 39 | 54 | — |

Values are % amino acid identity (above the diagonal) or similarity (below the diagonal). They were obtained by using the program genedoc from the sequence alignments shown in Fig. 3.

Gibberellin 2-Oxidase cDNAs from A.

thaliana. The predicted amino acid sequence of the P. coccineus GA 2-oxidase cDNA clone was used to search for closely related sequences in databases. Two Arabidopsis partial genomic sequences, T3M9-Sp6 and T24E24TF, with high amino acid sequence identity with the sequence of PcGA2ox1 were present in the Genomic Survey Sequences database, and a third, full-length sequence, T31E10.11, was present in GenBank. A cDNA clone (M7–3) that had been obtained from developing seeds of Marah macrocarpus also was closely related, with 63% amino acid identity with PcGA2ox1, although no function could be assigned to its gene product after heterologous expression (18).

Genomic fragments were obtained for T3M9-Sp6 and T24E24TF by PCR, and these were used to probe Northern blots of poly(A)+ RNA extracted from different Arabidopsis tissues. Highest transcript abundance for both genes was found in flowers (Fig. 4A). Consequently, poly(A)+ RNA from flowers was used to produce a cDNA library, from which cDNA clones corresponding to both genes were isolated by probing with the respective PCR products. The clones, designated AtGA2ox1 (from T3M9-Sp6) and AtGA2ox2 (from T24E24TF), appeared to be full-length by comparison with PcGA2ox1 and contained ORFs of 987 and 1,023 bp, respectively, encoding proteins of 329 (Mr 36,731) and 341 aa (Mr 38,457). Cell lysates after expression of each cDNA in E. coli converted [14C]GA9 to radiolabeled GA51, confirming that the cDNAs encoded GA 2-oxidases. AtGA2ox2, but not AtGA2ox1, also produced GA51-catabolite (Table 2). The third clone, designated AtGA2ox3, was obtained by reverse transcription–PCR by using poly(A)+ RNA extracted from flowers as template. The cDNA had an ORF of 1,005 bp encoding a protein of 335 aa (Mr 38,216). The expression product of AtGA2ox3 in E. coli converted [14C]GA9 to radiolabeled GA51.

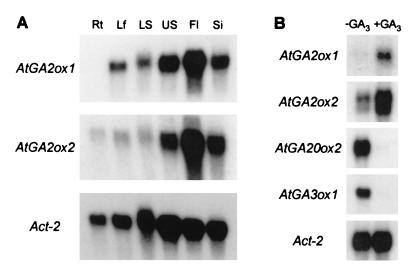

Figure 4.

Expression of GA 2-oxidase genes in Arabidopsis. (A) Tissue distribution of transcript in ecotype Columbia. Northern blots of poly(A)+ RNA (5 μg) from roots (Rt), leaves (Lf), lower stems (LS), upper stems (US), flowers (Fl), and siliques (Si) were hybridized to 32P-labeled cDNA for AtGA2ox1, AtGA2ox2, and actin (Act-2 gene, base pairs 1447–1832) (28). (B) Effect of GA on transcript abundance. Poly(A)+ RNA (5 μg) from immature flower buds of the GA-deficient ga1–2 mutant of Arabidopsis, either untreated (−GA3) or treated 24 h previously with 10 μM GA3 (+GA3), was hybridized to 32P-labeled cDNA for AtGA2ox1, AtGA2ox2, AtGA20ox2, AtGA3ox1, and Act-2.

Table 2.

Specificity of recombinant GA 2-oxidases for C19-GA substrates

| Recombinant enzyme | 14C-labeled GA substrate | 2β-HydroxyGA product | GA-catabolite product |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pc2ox1 | GA1 | 100 | — |

| GA4 | 83 | 17 | |

| GA9 | 87 | 13 | |

| GA20 | 86 | — | |

| At2ox1 | GA1 | 41 | — |

| GA4 | 25 | — | |

| GA9 | 91 | — | |

| GA20 | 50 | — | |

| At2ox2 | GA1 | 100 | — |

| GA4 | 77 | 23 | |

| GA9 | — | 100 | |

| GA20 | 100 | — | |

| At2ox3 | GA1 | 100 | Trace |

| GA4 | 86 | 14 | |

| GA9 | 100 | — | |

| GA20 | 25 | — |

Values are % yield by HPLC-radiomonitoring of products after incubation of cell lysates from E. coli expressing the cDNA with 14C-labeled GA substrate and cofactors for 2.5 h. Products and substrate were separated by HPLC, and products were identified by GC/MS (see Fig. 2). Where combined yield of products is <100%, the remainder is unconverted substrate.

Alignment of the derived amino acid sequences of the Arabidopsis GA 2-oxidases with those of PcGA2ox1 and other dioxygenases revealed conserved regions that are specific to the GA 2-oxidases (Fig. 3). As shown in Table 1, the GA 2-oxidases share 49–68% amino acid identity (68–84% similarity) with each other, but ≤27% identity (≤44% similarity) with the other GA dioxygenases.

Function of Recombinant GA 2-Oxidases.

The catalytic properties of the recombinant proteins obtained by expressing PcGA2ox1, AtGA2ox1, AtGA2ox2, and AtGA2ox3 cDNAs in E. coli were examined by incubating with a range of 14C-labeled GA substrates, consisting of the C19-GAs GA1, GA4, GA9, and GA20 and the C20-GAs GA12 and GA15. This last compound was incubated in both its closed and open lactone forms (see Fig. 1). Products were separated by HPLC and identified by GC/MS (typical HPLC-radiochromatograms for PcGA2ox1 are presented in Fig. 2). Enzyme activities were compared at pH 7.5; the activities of recombinant PcGA20ox1, AtGA20ox2, and AtGA2ox3 for 2β-hydroxylation of GA9 varied little between pH 6.5 and 8, and that of AtGA2ox1 peaked at pH 7 with no detectable activity at pH ≤5.9 and ≥8.1 (data not presented). Each of the C19-GAs was converted to the corresponding 2β-hydroxy product by the four enzymes. A second product was formed in incubations of GA9 with PcGA2ox1 or AtGA2ox2 and of GA4 with AtGA2ox2; these were identified as the corresponding catabolites by GC/MS. [14C]GA51 was converted to radiolabeled GA51-catabolite when incubated with PcGA2ox1 and AtGA2ox2, thus confirming that GA51 is an intermediate in the metabolism of GA9 to GA51-catabolite. However, GA51 was not metabolized by AtGA2ox1 and AtGA2ox3.

No conversion of GA12 was obtained with any of the enzymes, whereas GA15 was converted to a single product by PcGA2ox1 (Fig. 2) and AtGA2ox2. The open lactone form of GA15 (20-hydroxyGA12) was converted to the same product by AtGA2ox2 but less efficiently than the lactone form (data not presented), whereas there was no conversion of GA15 open lactone by PcGA2ox1 (Fig. 2). The mass spectrum of the product from GA15 is consistent with it being 2β-hydroxyGA15, although, because the authentic compound is not available for comparison, the identity of this product is tentative.

Comparison of the substrate specificities of the recombinant enzymes for the C19-GAs (Table 2) indicated that GA9 was the preferred substrate for PcGA2ox1, AtGA2ox1, and AtGA2ox2. GA4 was converted as effectively as GA9 by PcGA2ox1 and AtGA2ox3, but was a relatively poor substrate for AtGA2ox1 and AtGA2ox2. Although GA20 was 2β-hydroxylated more efficiently than GA4 by AtGA2ox1 and AtGA2ox2, no GA29-catabolite was detected after incubations with GA20, whereas low yields of GA34-catabolite were obtained when GA4 was incubated with PcGA2ox1, AtGA2ox2, and AtGA2ox3.

Expression of GA 2-Oxidase Genes in Arabidopsis.

Similar expression patterns for AtGA2ox1 and AtGA2ox2 were observed when Northern blots of poly(A)+ RNA from different Arabidopsis tissues were probed at high stringency with cDNA obtained by PCR (Fig. 4A). For both genes, highest transcript abundance was detected in flowers, siliques, and upper stems, with much lower levels in lower stems and leaves, whereas AtGA2ox3 mRNA was not detected in these tissues by Northern analysis. AtGA2ox2 transcript, but not that of AtGA2ox1, also was detected in roots.

Northern blot analysis of poly(A)+ RNA from immature flower buds of the GA-deficient ga1–2 Arabidopsis mutant with or without treatment with GA3 (5) indicated that AtGA2ox1 and AtGA2ox2 transcript levels were elevated by application of GA3 (Fig. 4B). In contrast, transcript abundance for the GA 20-oxidase gene AtGA20ox2 (At2353) (5) and the GA 3β-hydroxylase gene AtGA3ox1 (GA4) (22), which are high in the ga1–2 mutant, were reduced markedly after application of GA3 (Fig. 4B).

DISCUSSION

We used functional screening of a cDNA library in combination with a highly sensitive tritium-release assay of enzyme activity to isolate the first GA 2β-hydroxylase cDNA clone. The success of this cloning strategy was aided by preparing the cDNA library from a rich source of GA 2β-hydroxylase activity, late-developing seeds of P. coccineus (7). The function of the enzyme encoded by the cDNA was confirmed by incubating recombinant protein with 14C-labeled GAs and identifying the 2β-hydroxylated products by GC/MS. Unexpectedly, radiolabeled GA4 and GA9 gave additional products, which were identified as GA34-catabolite and GA51-catabolite, respectively, the latter being formed from GA51 by further oxidation at C-2. Although the mechanism is unknown, the conversion may proceed via 2-oxoGA9, which is the true product. The so-called catabolites, in which the γ-lactone is opened with formation of a double bond between C-10 and C-1, C-5, or C-9 (10), may be artifacts of the GC/MS procedure. This possibility is under investigation.

The derived amino acid sequence of the P. coccineus GA 2-oxidase contains the regions typically conserved in plant 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. However, the sequence is not closely related to any of the other known dioxygenases of GA biosynthesis, the most closely related being the 3β-hydroxylase encoded by the GA4 gene (AtGA3ox1) of Arabidopsis, with 26% amino acid sequence identity. Thus, it belongs to a new subgroup of this class of enzyme. We found three related sequences in databases of Arabidopsis genomic sequences and could show that their corresponding cDNAs encoded functional GA 2-oxidases. Thus, as for the GA 20-oxidases (5) and GA 3β-hydroxylases (23), the GA 2-oxidases are encoded by multigene families. However, in contrast to the 20-oxidase and 3β-hydroxylase genes, which show tissue-specific expression (5, 23), at least two of the 2-oxidase genes showed similar patterns of expression, with highest transcript abundance found in growing tissues. Also in contrast to the GA 20-oxidase genes and the 3β-hydroxylase gene, GA4 (AtGA3ox1), transcript abundance for these two 2-oxidase genes in the floral apex of the highly GA-deficient ga1–2 Arabidopsis mutant was lower than in the wild type (Columbia) and was increased by application of GA3. Down-regulation of GA 20-oxidase (5) and GA 3β-hydroxylase (22) gene expression by bioactive GAs provides evidence of a feedback mechanism, illustrated in Fig. 5, that would maintain active GA concentrations within certain limits. GA-stimulated up-regulation of the production of 2-oxidases, which metabolize the active GAs to inactive products, indicates there is also feed-forward regulation, which similarly would serve to stabilize GA concentration. Inactivation by 2-oxidation could occur either on the bioactive GAs, GA1 and GA4, or on their immediate non-3β-hydroxylated precursors, GA20 and GA9, which appear to be equally acceptable as substrates. Interestingly, it has been shown recently that a second Arabidopsis GA 3β-hydroxylase gene, which is expressed predominantly during seed germination, is not regulated by GA (23).

Figure 5.

Model showing feedback (dotted line with ⊣) and feed-forward (dotted line with ▸) regulation of GA biosynthesis.

The recombinant 2-oxidases converted several different C19-GAs, but failed to oxidize GA12, a C20-GA. PcGA2ox1 and AtGA2ox2 converted GA15, which is a C20-GA with a C-19-C-20 lactone that mimics the C19-GA structure, to putative 2β-hydroxyGA15, whereas, when the lactone of GA15 was opened, it was hydroxylated less effectively by AtGA2ox2 and not at all by PcGA20ox1. This preference for C19-GA substrates may not be shared by all 2-oxidases, because many plants accumulate 2β-hydroxy C20-GAs, including 2β-hydroxyGA12 (GA110) (24). The P. coccineus and Arabidopsis 2-oxidases differed in their capacity to hydroxylate C19-GAs, although GA9 was converted efficiently by each enzyme. It has been suggested from work with partially purified preparations from seeds of pea (P. sativum) (11) and French bean (P. vulgaris) (12) that such tissues contain at least two GA 2β-hydroxylases with different substrate specificities. One of the activities from imbibed French bean embryos hydroxylated GA4 and GA9 more effectively than GA1 and GA20 (12) and, thus, resembles the activity of the recombinant P. coccineus GA 2-oxidase. The derived amino acid sequences of the 2-oxidases contain no obvious organellar targeting sequences, suggesting that they are cytoplasmic, as also is indicated by the pH profiles for the activities of the recombinant proteins.

In developing seeds of pea, formation of GA29-catabolite occurs mainly in the testae, whereas both testae and cotyledons have GA20 2β-hydroxylase activity (25). Further evidence that 2β-hydroxylation and catabolite formation are catalyzed by separate enzymes in this species was obtained by Ross et al. (26) from substrate-competition studies. Both steps are impaired in seeds of the sln pea mutant, whereas 2β-hydroxylation, but not catabolite formation, was blocked in vegetative tissues, leading to the suggestion that SLN is a regulatory gene that controls two structural genes involved in GA catabolism (26). It is clear from our results with recombinant enzymes that a single GA 2-oxidase can catalyze both steps and, therefore, SLN could encode such an enzyme. The findings in pea could be explained by the presence of several functionally different GA 2-oxidases, one of which is encoded by SLN. The existence of GA 2-oxidases that produce catabolites from 2β-hydroxyGAs as their primary activity cannot be discounted, particularly in species such as pea, in which the catabolites are major products.

The availability of cDNAs encoding 2-oxidases provides an excellent opportunity to modify GA content in transgenic plants. High-level expression of such cDNAs may result in reduced amounts of bioactive GAs and, thereby, offers an alternative to the application of chemical growth retardants for the control of plant development. Above all, it now will be possible to determine how GA catabolism is regulated by endogenous and environmental signals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. P. Gaskin and Mr. M. J. Lewis for GC/MS analysis, Dr. J. R. Lenton for provision of plant material, and Dr. A. Crozier for the gift of [3H]GA9. This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the Sugar Beet Research and Education Committee. IACR receives grant-aided support from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council of the United Kingdom.

ABBREVIATION

- GA

gibberellin

Footnotes

References

- 1.Hooley R. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;26:1529–1555. doi: 10.1007/BF00016489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hedden P, Kamiya Y. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1997;48:431–460. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lange T. Planta. 1998;204:409–419. doi: 10.1007/s004250050274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.García-Martínez J L, Lopez-Diaz I, Sánchez-Beltrán M J, Phillips A L, Ward D A, Gaskin P, Hedden P. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;33:1073–1084. doi: 10.1023/a:1005715722193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillips A L, Ward D A, Uknes S, Appleford N E J, Lange T, Huttly A K, Gaskin P, Graebe J E, Hedden P. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:1049–1057. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.3.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albone K S, Gaskin P, MacMillan J, Sponsel V M. Planta. 1984;162:560–565. doi: 10.1007/BF00399923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Durley R C, MacMillan J, Pryce R J. Phytochemistry. 1971;10:1891–1908. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frydman V M, Gaskin P, MacMillan J. Planta. 1974;118:123–132. doi: 10.1007/BF00388388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacMillan J, Seaton J C, Suter P J. Tetrahedron. 1962;18:349–355. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sponsel V M, MacMillan J. Planta. 1980;150:46–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00385614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith V A, MacMillan J. Planta. 1986;167:9–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00446362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griggs D L, Hedden P, Lazarus C M. Phytochemistry. 1991;30:2507–2512. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith V A, MacMillan J. J Plant Growth Regul. 1984;2:251–264. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hedden P, Graebe J E. J Plant Growth Regul. 1982;1:105–116. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamiya Y, Graebe J E. Phytochemistry. 1983;22:681–689. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lange T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6553–6558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verwoerd T C, Dekker B M M, Hoekema A. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:2362. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.6.2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacMillan J, Ward D A, Phillips A L, Sánchez-Beltrán M J, Gaskin P, Lange T, Hedden P. Plant Physiol. 1997;113:1369–1377. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.4.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Ed. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coles J P, Phillips A L, Croker S J, García-Lepe R, Lewis M J, Hedden P. Plant J. 1999;17:547–556. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valegard K, van Scheltinga A C T, Lloyd M D, Hara T, Ramaswamy S, Perrakis A, Thompson A, Lee H J, Baldwin J E, Schofield C J, Hajdu J, Andersson I. Nature (London) 1998;394:805–809. doi: 10.1038/29575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiang H H, Hwang I, Goodman H M. Plant Cell. 1995;7:195–201. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamaguchi S, Smith M W, Brown R G S, Kamiya Y, Sun T P. Plant Cell. 1998;10:2115–2126. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.12.2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Owen D J, Mander L N, Storey J M D, Huntley R P, Gaskin P, Lenton J R, Gage D A, Zeevaart J A D. Phytochemistry. 1998;47:331–337. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(97)00577-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sponsel V M. Planta. 1983;159:454–468. doi: 10.1007/BF00392082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ross J J, Reid J B, Swain S M, Hasan O, Poole A T, Hedden P, Willis C L. Plant J. 1995;7:513–523. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaskin P, MacMillan J. GC-MS of the Gibberellins and Related Compounds: Methodology and a Library of Spectra. Bristol, U.K.: Cantock’s Enterprises; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 28.An Y Q, McDowell J M, Huang S R, McKinney E C, Chambliss S, Meagher R B. Plant J. 1996;10:107–121. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1996.10010107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]